(Los Angeles) - Los Angeles County officials should move urgently to test a backlog of more than 12,000 rape kits - the physical evidence collected after a sexual assault - to ensure justice for rape victims, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

The 68-page report, "Testing Justice: The Rape Kit Backlog in Los Angeles City and County," reveals that the backlog of untested rape kits in Los Angeles County is larger and more widespread than previously reported. Through dozens of interviews with police officers, public officials, criminalists, rape treatment providers, and rape victims, the report documents the devastating effects of the backlog on victims of sexual abuse.

"Women who are raped have a right to expect police to do all they can to thoroughly investigate their case, but in LA they often feel betrayed to learn that their rape kits are never even tested," said Sarah Tofte, researcher with Human Rights Watch's US program and author of the report. "And in some cases, failure to test means that a rapist who could have been arrested will remain free."

Women who report being raped are asked to undergo a lengthy, extensive examination to collect DNA and other physical evidence that might identify their attacker, corroborate testimony about the assault, or connect their case to other rape crime scene evidence. The resulting rape kit is then booked into police evidence. However, although rape victims may believe it is automatically tested, that is often not the case in Los Angeles County. Rape treatment providers told Human Rights Watch that victims assumed silence from the officers investigating their case simply meant no evidence was found, or that there was no DNA match.

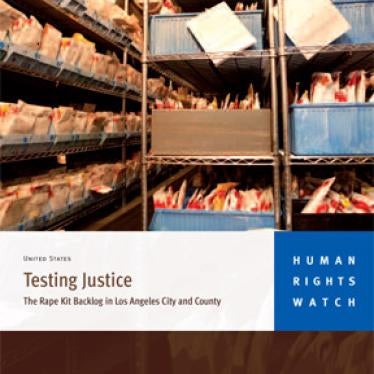

But Human Rights Watch analyzed data from the Los Angeles Police Department, the Los Angeles Sheriff's Department, and Los Angeles County's 47 independent police departments, and found that as of March 1, 2009, there were at least 12,669 untested rape kits sitting in storage facilities. In those cases, officers never sent the kits on for forensic testing.

Of these 12,669 untested kits, at least 1,218 are from unsolved cases in which the attacker was a stranger to the victim. And 499 kits are attached to cases past the 10-year statute of limitations for rape in California, making it impossible to prosecute the alleged assailants even if they were to be identified. Under California law, if those 499 kits had been opened within two years of the attack, the statute would no longer apply. Thousands more rape kits were destroyed untested.

The backlog grew even as the Police and Sheriff's Departments received millions of federal dollars from the Debbie Smith DNA Backlog Grant, a program the US Congress created to address rape kit backlogs, the effect of which is blunted by the fact that grantees can use the money to test any kind of DNA backlog.

Human Rights Watch's report also contains previously unpublished data on the extent of the rape kit backlog in the 47 cities in Los Angeles County that have independent police departments. For example, records obtained by Human Rights Watch show that the City of Long Beach booked 1,911 rape kits into evidence in the past 15 years. Of those, 51 were sent to the crime lab, an estimated 780 untested kits were destroyed, and 1,072 currently sit untested in their police storage facility. (A chart of data from the 47 cities is available in chapter VI of the report.)

Backlogs of rape kits exist at police stations and crime labs throughout the United States, but nowhere is the problem known to be more acute than Los Angeles. The accumulation of rape kits in Los Angeles County is due to a combination of police discretion regarding which rape kits get tested; a lack of financial commitment to testing; and the length of time it took officials to acknowledge the nature and extent of the problem, Human Rights Watch said.

"Failing to test rape kits denies justice to women who've suffered sexual violence," said Tofte. "If officials had spent federal money to test more kits, they might have prevented future rapes and allowed for prosecution in cases that are now beyond the statute of limitations."

The backlog can have tragic results. In one case documented in the report, in the time it took police to test one woman's rape kit, the alleged perpetrator had attacked at least two other victims, including a child.

Law enforcement officials told Human Rights Watch they sometimes delayed submitting a kit for testing because they did not believe a crime had occurred. Officials also said they tested every kit in which the attacker was a stranger to the victim, but the subsequent backlog count showed this not to be the case. Testing the rape kits can do more than isolate an unknown attacker's DNA: it can connect evidence from different crime scenes and it can exonerate innocent suspects.

"The Police and Sheriff's Departments have agreed to test all rape kits now in the backlog and all those collected in the future," Tofte said. "Now officials need to enforce this policy as part of a wider reform of the way rape is investigated."

The US has specific obligations under international human rights law that require reasonable steps be taken to secure essential forensic evidence from incidents of sexual violence. In order to meet these obligations and eliminate their backlogs, Human Rights Watch called upon the Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles Sheriff's Department to:

- Enforce policy requiring every booked rape kit to be sent to the crime lab and tested;

- Identify the crime lab resources necessary to test every booked rape kit - those currently in the backlog and those collected in the future - in a timely manner;

- Identify the police department resources necessary to pursue the investigative leads generated from testing every booked rape kit;

- Prioritize funding for the resources necessary to eliminate the rape kit backlog, test every future rape kit, and pursue investigative leads from rape kit testing;

- Implement a system to inform sexual violence victims of the status of their rape kit test; and,

- Preserve every booked rape kit until it is tested.

Human Rights Watch also called on the Mayor of Los Angeles, the Los Angeles City Council, and the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to make funding for the testing of rape kits a priority in their 2009-2010 budgets.