The October 23 conviction by a military tribunal of 15 soldiers for the massacre of 31 civilians in Muyinga province in 2006 is an important blow against impunity in Burundi, Human Rights Watch said today. The series of killings is among the worst atrocities committed by state security forces since President Pierre Nkurunziza took office in 2005.

"After more than two years, the families of the Muyinga victims have finally seen some justice," said Alison Des Forges, senior advisor to Human Rights Watch's Africa division. "Let's hope this means that Burundi intends to end the pattern of horrible abuses against its people."

A military tribunal in Muyinga sentenced three soldiers - Commandant Eliezer Manirambona, Sergeant Ntirampeba, and Chief Corporal Nzorijana - to life in prison, and seven others to 10-year sentences for complicity in the killings. Four other soldiers were found guilty of failing to intervene to stop the crime and were sentenced to two years in prison. The tribunal acquitted nine soldiers of failing to act in response to the crime after they convinced the court that they had promptly informed their superiors of the killings.

The tribunal found Colonel Vital Bangirinama, commanding officer of the soldiers implicated in the massacre, guilty in absentia and sentenced him to death. He fled Burundi in January 2008 after learning that the military prosecutor intended to arrest him on a warrant that had been pending since October 2006. Human Rights Watch opposes trials in absentia and the death penalty, and calls upon the government to make every effort to promptly apprehend and retry Bangirinama.

None of the civilian officials implicated in the case, including local administrative officials and intelligence agents, has been prosecuted.

Background

Between June and August 2006, soldiers of the National Defense Forces (Forces de la Défense Nationale, FDN) transported at least 31 civilians from the Mukoni military camp, where they were being held illegally, to the Ruvubu National Park. There they killed the civilians, dumping their bodies in the river. Military Prosecutor Donatien Nkurunziza (no relation to President Nkurunziza) told the court that Col. Bangirinama, then head of Burundi's Fourth Military Region, ordered his subordinates, including Nzorijana, Ntirampeba, and Manirambona, to carry out the killings.

The victims, some or all of whom were suspected of supporting the rebel Party for the Liberation of the Hutu People (Parti pour la Libération du Peuple Hutu-Forces Nationales pour la Libération, Palipehutu-FNL), had been arrested by local administrative officials and agents of the intelligence service (Service National de Renseignement, SNR).

The appearance of bodies in the river, as well as inquiries from the families of victims, drew national and international attention to the massacre and embarrassed the recently-installed government. Following early investigations, authorities arrested several low-ranking soldiers. They also arrested the head of the intelligence service in Muyinga, Dominique Surwavuba, but he was released in 2007 and has not been brought to trial. Other civilians, including local officials, implicated by witnesses have not been arrested.

Early investigations led to a warrant for the arrest of Col. Bangirinama, but President Nkurunziza suspended execution of the warrant. In December 2007, the military prosecutor again prepared to arrest Bangirinama, but he fled the country, apparently having been warned that his arrest was imminent. Burundian police filed an international arrest warrant with Interpol, the international policing agency, in February 2008; but Bangirinama's whereabouts remain unknown.

The case of other military defendants was bounced between civilian and military jurisdictions several times, until the Supreme Court ruled in mid-2008 that it should be heard before a military tribunal. Many soldiers from the local military camp attended the court sessions. On one occasion the military prosecutor underlined for them a lesson of the trial, pointing out that soldiers who executed illegal orders themselves bore responsibility for their conduct.

Human Rights Watch, along with families of the victims, local human rights groups and the United Nations Integrated Office in Burundi (BINUB), worked for two years to press the government for justice and expressed satisfaction afterward with conduct of the trial. The Burundi rights groups include the Association for the Protection of Human Rights and Detainees (Association pour la Protection des Droits Humains et des Personnes Détenues, APRODH) and Ligue Iteka. Human Rights Watch urged the government to bring others implicated in the killings - intelligence agents and local officials - to trial.

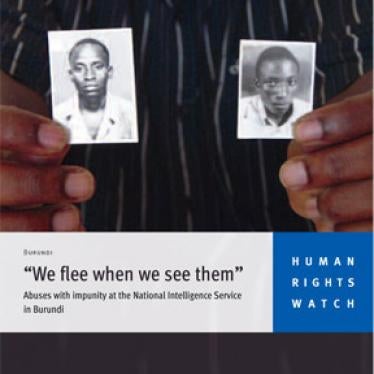

Families of victims have sought damages from the state. As one victim's widow told Human Rights Watch: "I have 10 orphans who lost their father. We need damages to assure the future of our children." The tribunal postponed the damages proceedings for several weeks.

"Those who suffered abuse at the hands of the Burundian army have rarely been able to hope for any reparations," said Des Forges. "Recognizing their rights to damages would set another positive example in the fight against these abuses."