(Lagos, April 25, 2006) - Government policies that discriminate against “non-indigenes,” loosely defined as people who are not native to an area, have relegated millions of Nigerians to the status of second-class citizens and must be reversed by Nigeria’s federal government, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

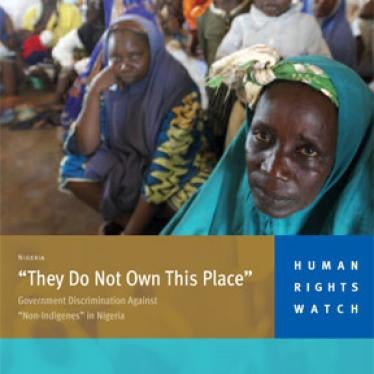

The 64-page report, "'They Do Not Own This Place': Government Discrimination Against 'Non-Indigenes' in Nigeria," documents the harmful impact of these discriminatory policies on the human rights of many Nigerians in violation of the Nigerian constitution and international human rights law. It also shows how these policies of discrimination exacerbate interethnic and interreligious tension in ways that have sparked violence in many different parts of the country.

“These policies marginalize millions of Nigerians and fuel the fires of ethnic and religious violence,” said Peter Takirambudde, executive director of the Africa division at Human Rights Watch. “The federal government must end its shameful record of indifference by acting decisively to eradicate this discrimination.”

According to common understanding in Nigeria and as a matter of government policy, the indigenes of any given locality are those persons who can prove that they belong to the ethnic community whose ancestors first settled the area. Everyone else is considered a non-indigene, no matter how strong their ties to the communities they live in.

State and local governments throughout Nigeria have enacted policies that discriminate against non-indigenes and deny them access to some of the most important avenues of socio-economic mobility open to ordinary Nigerians. In many states, non-indigenes are openly denied the right to compete for government jobs and academic scholarships, while state-run public universities subject non-indigenes to discriminatory admissions policies and higher fees. Instead of working to combat this discrimination, federal government policies have often served to legitimize and reinforce it.

Many Nigerians argue that the concept of indigeneity has a role to play in meeting the challenges inherent in governing a society as diverse as Nigeria’s, which is made up of more than 250 different ethnic groups. In particular, many believe that the distinction between indigenes and others helps to guarantee smaller ethnic communities the power to maintain some degree of cultural autonomy, including control over their chieftaincies and other institutions of traditional governance. But government policies that deny non-indigenes the material benefits of citizenship are nothing more than a perversion of this rationale, as they serve no legitimate purpose other than to exclude many Nigerians from rights they should be able to enjoy as citizens.

“Discriminatory indigeneity policies often reflect a truly cynical set of political calculations,” said Takirambudde. “Many Nigerian politicians are simply trying to curry favor with their indigene constituents by excluding non-indigenes from scarce opportunities that should be available to all.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed several dozen people from ethnic communities who are labeled “non-indigenes” by their state and local governments. Many spoke of being forced to abandon their hopes of university education because of their non-indigene status, and of being locked out of scarce employment opportunities as civil servants, police officers, or military recruits. In some cases, non-indigene civil servants have been subjected to mass purges from state civil services in order to create more jobs for indigenes of the state. As one young man in Kaduna state put it, as a non-indigene “you are completely disqualified from everything.”

This discrimination is especially burdensome for the increasing number of Nigerians who are unable to prove that they are indigenes of any place at all; such individuals are discriminated against as non-indigenes in every part of Nigeria. Some Nigerians are labeled “non-indigenes” of communities their families have lived in for more than a century, even though they no longer remember from where their ancestors are supposed to have migrated.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed government officials at the state, local, and district level, many of whom were openly contemptuous of the problems of their non-indigene constituents. One district official in Plateau State, asked how he felt about the plight of local Jarawa residents he labeled non-indigenes even though they cannot claim indigene status anywhere else, replied, “I don’t care. They do not own this place. We do.”

Other officials insisted that they would support reform but that it was politically impossible for them to tackle the issue unless federal authorities took the lead by ordering state and local governments to roll back discriminatory policies.

Beyond their immediate impact, government policies that discriminate against non-indigenes have also helped to fuel chronic patterns of interethnic and interreligious violence in some parts of Nigeria. The population is deeply divided along ethnic, religious, and other lines, and frequent intercommunal clashes have claimed more than 10,000 lives since the end of military rule in 1999 alone. Because the lines between “indigenes” and “settlers” often overlap with these already volatile ethnic and religious divides, government indigeneity policies have frequently exacerbated other sources of tension to the point of violence.

“Nigeria has struggled without success to contain ethnic and religious violence that has killed thousands,” said Takirambudde. “Disastrous government policies on indigeneity have undercut those efforts by creating additional sources of tension and resentment.”

In some places, such as Jos and Yelwa in Plateau state, ethnic conflict has erupted because groups disagree over who is and is not entitled to claim indigene status in any given area. Such arguments are made more intense and bitter by the discrimination endured by whichever side loses the debate. In other cases, as for example in Kaduna state, local officials have fueled Christian-Muslim tensions by improperly denying certificates of indigeneity to people who do not share their religion.

For these and other reasons, some Nigerians have come to feel that ending the discrimination they face as non-indigenes is a goal worth shedding blood to achieve. One Ijaw man in Warri, who had participated in interethnic violence there in 2003, expressed this sentiment to Human Rights Watch by asking rhetorically, “Why not fight it out instead of remaining slavish to this condition?”

Human Rights Watch called on Nigeria’s federal government to immediately pass legislation that outlaws government discrimination against non-indigenes in all matters that are not purely cultural or related to traditional political institutions. The government must then vigorously enforce that legislation and work to educate the public on the harmful consequences of discrimination against non-indigenes.

Selected testimonies from the report:

I have lived in Kaduna since 1963. This is where we belong… This is my home whether they accept it or not—I am a citizen of the state and the constitution says I have a right to live here.

—A non-indigene Igbo resident of Kaduna city.

We feel dissatisfied and unhappy when people tell us that we are not of this place. We have been here for over 200 years. Our parents were born here and we ourselves were born here. We know no other place other than here and so we have nowhere else to go.

—An elderly Hausa resident of Zangon-Kataf in southern Kaduna. Zangon-Kataf’s Hausa community has suffered widespread harassment and even violence since their community was burned to the ground in 1992.