Last week's presidential election in Azerbaijan ensured that the current government would maintain its control over the country's significant oil reserves. In the former Soviet bloc's first dynastic succession, Ilham Aliyev, son of the ailing Communist-era holdover Heydar Aliyev, has now become president.

Many in Western policy circles viewed this transition as critical to the stability of billions of dollars of investments in the country's energy sector. The violent events of the past few days should make them think otherwise.

International and domestic monitors reported widespread irregularities in the Oct. 15 election. I saw it myself at a polling station where the election chief kicked out local observers and made off with the votes, claiming she had to take a nap.

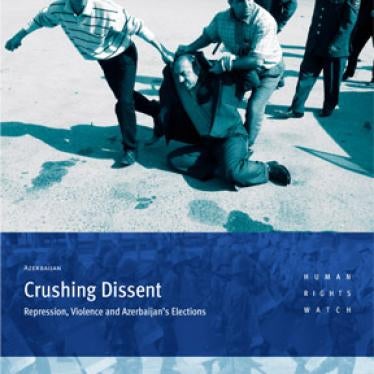

The government clearly stole the election, and then brutally beat hundreds of people who poured out in the streets in protest. The day after the election, I watched from the roof of a hotel in Baku as thousands of riot police beat protesters unconscious. Afterward the riot police raised their shields to the sky and turned their batons into drumsticks, celebrating the victory of intimidation.

Now hundreds have been arrested, while Isa Gambar, the opposition leader, is effectively under house arrest and activists from his Musavat party are being beaten and detained all over the country. Everyone I speak to is scared.

The violence surrounding the election was shocking yet predictable, as the government for years has shut the opposition out of the political process. In the months leading up to the poll, Azerbaijani authorities blatantly manipulated the electoral process to ensure that Ilham Aliyev would inherit his father's presidency. The opposition had nowhere to go but the streets.

More astonishing, however, were the public assessments of the election made by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe and the Council of Europe. Their election-monitoring missions in Azerbaijan took due note of the violence and election irregularities, but their overall appraisals were alarmingly upbeat. The OSCE mission chief, Giovanni Kessler, said the election showed "an increased vitality of political life and serious efforts in Azerbaijan towards democracy and international standards.” Meanwhile, the head of the Council of Europe's parliamentary delegation, Guillermo Martínez Casañ, said he hoped the election could "mark the beginning of a new era in Azerbaijan in which progress could be achieved through cooperation of all democratic forces in the country."

The Aliyev government has a terrible human rights record, and a long history of imprisoning its opponents, rigging elections and breaking up public protests with excessive violence. International and local observers have charged that the country's last national election, the parliamentary election of 2000, was blatantly fraudulent.

The international community is well aware of this sorry history, but it seems to want to wish it away so it can get on with business with the oil-rich country's government. Europe's foremost human rights body, the Council of Europe, admitted Azerbaijan in 2000 despite the country's disastrous parliamentary election. The Council of Europe did establish a body that monitors the country's democratic development and requires the government to report back on charges of election fraud. But this measure did little to restrain the government from repeating election fraud last week.

This time, the international community must not passively accept a violently stolen election. Azerbaijanis are justifiably tired of the corruption and arbitrariness of years of rule under the current government. They are growing increasingly suspicious of the West and its unwillingness to be tough on the Aliyev clan.

Moreover, letting the Azerbaijani government steal its election will embolden other governments to do the same. In the long run, this will contribute to more public discontent and destabilize this oil-rich region.

The writer observed the Azerbaijan election for Human Rights Watch.