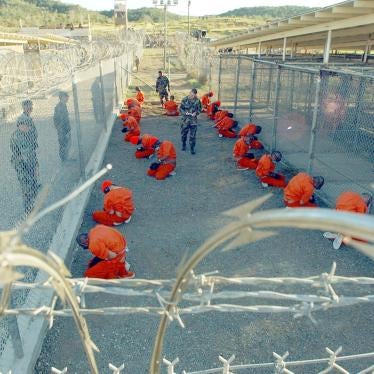

NEW YORK -- The Bush administration thinks it has a solution to the evidentiary and legal frustrations of prosecuting terrorist suspects: Designate them "enemy combatants" and detain them indefinitely without charge or trial. But that raises the question: Is this an appropriate response to a serious security threat or a ploy to circumvent the U.S. Constitution?

A federal court in New York will soon rule on the matter, and Congress is considering hearings. In doing so, they should look beyond the issue of detention to ask the surprisingly related question: Would it have been appropriate to shoot the suspects summarily?

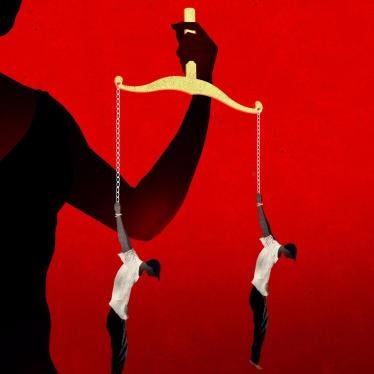

If a person is a criminal suspect, the Constitution requires the police to avoid using lethal force unless necessary to stop an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury. But in the case of enemy combatants, the law of war permits them to be killed summarily, so long as they are not in custody or incapacitated. There is no duty to try to arrest or subdue enemy combatants.

Which law should apply? If we are reluctant to start summarily shooting terrorist suspects on American soil--I suspect most Americans would be--we also should be reluctant to designate them as enemy combatants in order to deny them their due process rights.

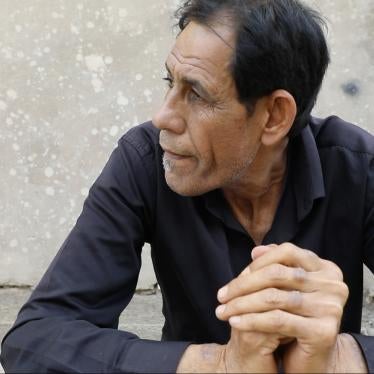

Take, for example, the case of Jose Padilla, presently before the court. The Bush administration claims that Padilla, an American citizen, is an enemy combatant because he allegedly came to the U.S. from Pakistan to detonate a radiological bomb. Padilla was seized in May upon his arrival at O'Hare International Airport and has been detainedwithout any due process rights ever since.

Leaks from the U.S. Justice Department suggest that Padilla was nowhere near carrying out his alleged plans, and thus posed no imminent threat of the sort that might require the preventive use of lethal force. So if Padilla was merely a criminal suspect, he could only have been arrested. But if he came to wage war as an enemy combatant, as the Bush administration claims, he could have been shot in cold blood in the public concourses of O'Hare, regardless of any immediate danger he posed.

I believe many Americans would have had qualms about Padilla being summarily shot. In part that is because they don't believe that the U.S. government should rely on military force when the criminal justice system is available. In part it is because they don't believe that criminal acts of the type Padilla is alleged to have been plotting really constitute war.

For the time being, an armed conflict is still under way in eastern Afghanistan. Enemy soldiers there certainly qualify as combatants. But the Bush administration has spoken about a global war on terrorism. Does that mean that terrorist suspects anywhere in the world can be treated as combatants and shot? Or should the campaign outside of Afghanistan be treated as a matter for law enforcement, at least where there is a functioning criminal justice system to handle those cases?

Consider an analogous situation in which armed conflict is raging in a distant country, U.S. troops are deeply involved, and enemy forces are sending clandestine agents to the U.S. to engage in secret operations that will kill thousands each year. The war on terrorism? No, the war on drugs. The drug war certainly involves real armed conflict in places such as Colombia, but when it gets to U.S. shores it is only rhetorically war--a hortatory call for law enforcement, not a mandate for the military to step in.

The proof is how we go about fighting the war on drugs domestically. We arrest and prosecute drug dealers. As much as many Americans may abhor drug trafficking, we don't summarily shoot drug dealers in the street. But such killings would be appropriate if the war on drugs were a real war and the drug dealers were enemy combatants.

Outside of Afghanistan, the war on terrorism is similarly rhetorical, even if American lives are at risk. At least where law enforcement is possible, these crimes and threatened crimes, serious as they are, must be pursued through the criminal justice system with its attendant due process rights. If we are uncomfortable summarily shooting terrorist suspects on the streets of New York (or Hamburg or London), then we should also be uncomfortable declaring them enemy combatants to circumvent their due process rights and detain them summarily.

This insight won't solve all the legal problems now working their way through the courts. Someone such as Louisiana-born Yasser Esam Hamdi may well be an enemy combatant because he was captured on the battlefield in Afghanistan, but he should still be entitled to judicial review of his detention because he is an American citizen detained in the U.S.

But Jose Padilla and suspects like him captured far from the battlefield should not be treated as enemy combatants. If they are plotting serious crimes, they should be charged and tried with full due process rights.