Burma Elections 2015

Under military rule since 1962, Burma will on November 8 hold its first contested national elections since 1990, when the military annulled an overwhelming victory by the opposition National League for Democracy. While the reform process begun in 2011 has led to significant human rights improvements in areas such as freedom of expression and association, the process has gone into reverse in the past two years, with increasing numbers of politically motivated arrests and the passage of discriminatory laws aimed at the Rohingya and the broader Muslim community. Parliamentary elections are seen as both a milestone and a test of the military-backed government’s commitment to the reform process and as the first, key step toward building a democratic state. While mass campaign rallies are a welcome sign of change, the lack of an independent election commission, ruling party dominance of state media, and mass disenfranchisement of voters remain as key concerns. In the days leading up to and following the election a team of Human Rights Watch staff will be monitoring the electoral process and the human rights situation in the country.

Voices of Change

(Rangoon) – One week after the election, with 99 percent of results announced, the National League for Democracy’s overwhelming victory points to a clear consensus among Burmese voters in their support for the NLD’s refrain, “Time for change.”

Throughout the two-month campaign period, the NLD’s slogan, theme song, and stump speeches all reiterated the theme of change for Burma. “The country needs change. That is why we say, ‘Time for change’ – to reflect the will of the people,” Aung San Suu Kyi said to the crowd of 40,000 gathered in Rangoon a week before the election. The ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) had picked up the thread with its late campaign promise, “We have been changing,” but to little effect. In Irrawaddy Region, President Thein Sein’s final hometown speech came with a rebuttal to the NLD buzzword: “We have changed from a military regime to a democratic government elected by the people. What more change do you want?”

In the wake of NLD’s victory, the question now shifts to whether the election can truly bring genuine change, given the flawed 2008 constitution that reserves 25 percent of parliament seats for the military and blocks Suu Kyi from the presidency.

With the challenges of negotiations and power transfer ahead, it’s worth returning to the voices of voters from around the country in response to a question we posed in the weeks leading up to the election: Do you think November 8 can bring real change?

Here are some of their answers.

“If it is free enough – I don’t think about fair elections – but if it is free, I think some things will change. At least we can see some cohesion in parliament. But it cannot change the important things, because the army still has 25 percent of parliament. They still choose the three major ministers. All the bureaucracy, the General Administration Department and so on, will still be under the military.”

“The elections alone cannot fix our problems. But we must have the right to select our leaders.”

“Maybe things will change – but we need educated voters who critically think about the future of our country.”

“For the country to change, we have two needs. Peace and economic development. Will this happen?”

“Change will be hard but possible. We need more engagement with organizations who work for a common purpose, and then we can change something.”

“People think the NLD will bring change and solve everything. They have too high expectations. We will only have more problems.”

“Thein Sein says, ‘We changed.’ You changed, yeah, yeah, you changed the color, you changed the uniform. That’s it.”

“We all expect real democracy. This is our first priority, to be a real democratic country. I want to change us to a real democracy – but this means all people have to be included.”

“It is not only the inside of the constitution that needs change, it is the structures – of parliament, the military. We have to fight from the outside, from the community. Twenty-five percent of parliament is military. They hold the power. It is impossible to change from the inside alone.”

“If the UEC [Union Election Commission] is free and fair, the election will result in a real [government]. But it is not enough to change the outside. You have to change the mindset.”

“After 2012, 2013, I saw positive change. Now I don’t see positive change. Whatever may be the 2015 election results, there are no military–civilian relations. So the military can just seize power, like Thailand.”

“We need education. The mentality of the government and of the military will not change. They still remain in power doing the same things. One thing I hope for the future is that we have some more freedom. However, that cannot satisfy the situation. We have to work to extend our space. I’ve seen space for civil and political societies expand. We want more and more.”

“I hope there will be change. There are two things we need to focus on first – the education system, and decentralization.”

“Yes we have big hopes. Big hopes mean we need real change. Change to the system, governance, legal reform, and education. People’s perspective needs to be changed too. We used to have a really good education system, used to respect each other, and used to listen to each other. Now the younger generation is changed because of the weak education system. I feel that we are losing our traditional culture of being kind and gentle. We need change to find those kind of value systems again.”

“When the wind comes, you can try to move your boat. But if it’s still tied to the edge of the harbor, it won’t go anywhere.”

“I hope so, because I want to hold events like human rights days with easy and open permission. I want to host regional conferences. I want the change so that it is easy to learn.”

Striving for Rights through Politics in Kachin

(Myitkyina) – Despite their concerns about an election process that they see as flawed, some Kachin activists are seeking change through politics by contesting the November 8 elections. Mar Khar is a human rights lawyer. He loses most of his cases, he says, laughing. “As a lawyer and human rights activist, I don’t feel so powerful,” he said. “But if I am in government, then I can advocate for human rights.”

Mar Khar is a candidate for the Kachin Democratic Party (KDP) who is hoping to win a seat in the state legislature from Myitkyina. With a long running civil war, he notes that there are many serious human rights violations by the military deployed to fight against the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and other armed groups operating in Kachin state. Mar Khar says that ethnic minorities in the country are regarded as nanning, or inferior, and adds that this is the reason Burmese soldiers believe they can subject them to a range of human rights violations including torture, extrajudicial executions, and enforced disappearances. “The number of human rights violations committed by the military is very high. But only a few cases can be raised [with the authorities]. Especially in the rural areas, people are afraid even to report these crimes.”

He shows pictures on his phone of a man that escaped military custody after severe torture. “The victim wanted to file a case, but his family was too worried about what might happen and discouraged him.” He described the case of two teachers who were allegedly raped and murdered by soldiers in January 2014, a charge that the Burma army denies. The military, he says, suspects every Kachin as a rebel supporter. “If you are Kachin, the military thinks they can kill you at any time.”

Bawk Ja of the National Democratic Force (NDF) says she knows this well. After receiving threats to her life from one of her military political opponents in the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), she is no longer running from her Hpakant constituency. She is contesting from Mytikyina instead.

Bawk Ja is leading a campaign against forced evictions and confiscation of land, particularly by the Yuzana company, which she says is owned by members of the military. She ran against former military general Ohn Myint in the 2010 election. Despite her significant initial lead, the Union Election Commission (UEC) eventually declared Ohn Myint the winner. She filed a complaint alleging voter fraud. In July 2013, she was arrested, she says, on politically trumped up charges, and was in prison for six months. But she is undeterred. “If I was contesting in Hpakant, I would win,” she says. “But even in Mytikyina, people are becoming more and more aware about illegal land confiscation because of my campaign.”

She thinks that the elections will not be free and fair. She points out a list of problems, including deeply flawed voter lists, and an election process that is biased towards the ruling party. But she still plans to try. “I want to win my seat so I am able to raise the issues of land grabbing in parliament. Military cronies are now dominating parliament. But when I raise these issues, the people will support me. I will be able to convince the military.”

Both Mar Khar and Bawk Ja are enjoying recent victories as rights activists.

The Supreme Court recently acquitted one of Mar Khar’s clients, Brang Yung, although it upheld the conviction of Lapai Gun, who was convicted for exactly the same crimes – both were accused of supporting the KIA. Brang Yung is still in jail, however, because the court order mistyped his prison identification number. Their wives, among the many internally displaced by the war, are waiting anxiously for Mar Khar to finish his election campaign so he can focus on the case. Mar Khar says he will continue his work as a human rights lawyer even if he wins. “I want to fight for the truth,” he says.

In June 2015, in an unprecedented gesture, the military returned about 200 acres of land it had previously confiscated in Samaw to over 50 households. Bawk Ja says this is the result of appeals from the community. She had written to members of parliament, the speaker, and the president. “I think it is possible for things to improve,” she says. “I can act as a mediator between the local people and the military.”

Both activists know that it will be a tough contest. There are multiple parties that will divide the vote. But it is an opportunity for human rights to win. Said Dau Nyoi, a local activist: “Many political parties talk about peace. Some talk about federalism. But none of them say much about justice and human rights.”

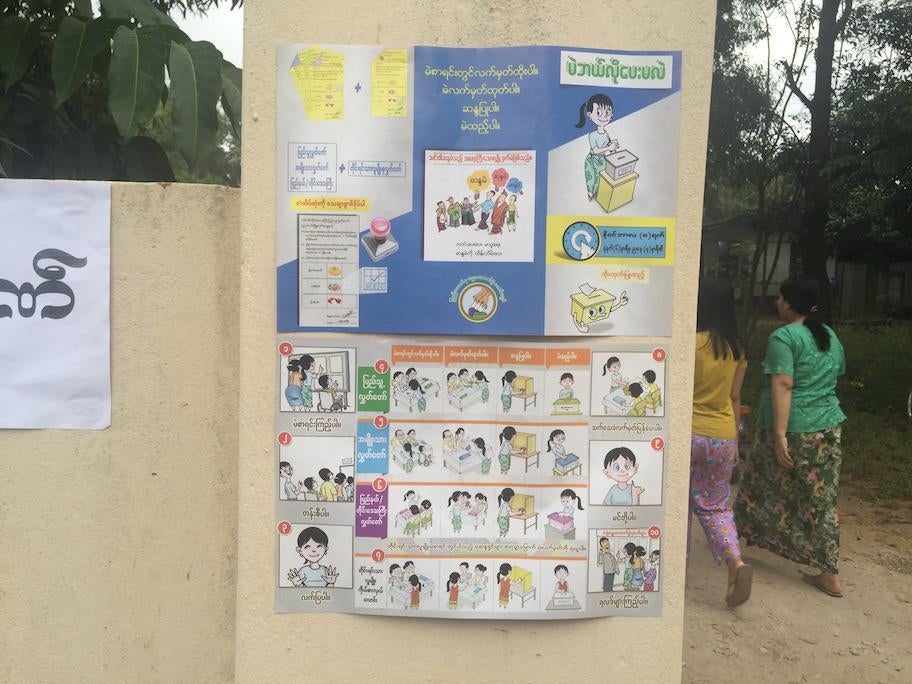

The Drumbeat of Voter Awareness

(Nyaung Shwe) – When Burma’s polling stations open tomorrow at 6 a.m., the local election observers of Justice Drum, a Shan State civil society collective, will be on the road much earlier, on motorbikes traversing dirt tracks 70 miles into the mountains as they head to reach isolated villages. The enthusiastic and committed staff of Justice Drum have, like many Burmese organizations, been feverishly busy on voter education for months, accessing many isolated and undeveloped communities in their area. The Burmese speakers of Justice Drum will need translators, as very few of the Pa-O and other ethnic groups in the nearby hills speak or read Burmese, the language used on all the ballot papers.

In this part of Shan State, a region populated by large numbers of ethnic Pa-O, Intha, and Shan ethnic groups, voter education must contend not just with rugged geography and poor roads, but also the large numbers of parties who are in the race. It’s not just the ruling Union State and Development Party (USDP) and the National League for Democracy (NLD), the two parties contesting nationally, but also two major Shan parties who are vying for dominance, as well as competing parties of Pa-O and Intha seeking local votes. On top of this, many local residents still hold residual fears of the security forces and officialdom, and what comes after Sunday’s polls.

The members of Justice Drum are enthusiastic about the elections, but realistic over how much it will or will not change people’s lives. One of them told me, “The campaigning has been great, it gives us the chance to be victorious. But we [CBOs] are still scared. How will normal people feel? They are still scared.” When asked if the process promises great democracy, he agrees, but then replies, “But what use is democracy if the laws are still there? The constitution is still there.” He said there was no violence, no overt intimidation, and that a Special Branch informer who tailed them was actually quite practically helpful: “He would help us along the way and take us places.” Voter education events in monasteries were not overshadowed by the Buddhist monk ultra-nationalist group the Ma Ba Tha, implicated in voter intimidation in several other areas around Burma.

All the party signs that have dotted the countryside for two months were taken down here on Friday, as per elections rules. As Justice Drum hits the road early tomorrow to observe elections in some of Burma’s most isolated areas, they will however pass voter education posters that do remain on trees, fences, and billboards, reminding people every vote counts. While much attention for these elections will be directed at large urban areas, prominent candidates, and potential trouble spots of communal tensions, the work of including many marginalized people in these parts of Shan State wracked by conflict since the 1950s is a good example of the generally positive voter awareness campaign that marks these polls.

In the Mon Battleground

(Moulmein) – It’s a quiet afternoon at the Mon National Party (MNP) headquarters in Moulmein’s Myaingtharyar quarter. The printing machines are shut off; rolled up campaign banners lean along the walls. Political campaigns have come to a close for a brief interlude before Sunday’s polls, and the local candidates sit drinking tea in the silence that follows weeks of campaign rally din.

Naing Ngwe Theim, the 94 year old party chair, and Naing Ngwe Thein, his 80 year old number two, talk about the trajectory of their party – one of two major Mon political groups – in terms alternately confident and resigned. The electoral process’ fundamental flaws are in many ways magnified within the borders of ethnic parties’ campaigns. The constitutional provision which guarantees 25 percent of national parliamentary seats to serving military officers also applies to regional and state parliaments. In Mon State, this means military representatives hold 8 of the 31 seats, leaving ethnic parties with an uphill battle toward securing a majority in their home states. Regional and state chief ministers are also presidential appointees. With political power almost fully centralized in Naypyidaw, an ethnic majority in state parliament would still wield little autonomy or control.

For members of the Mon community, these structural inequalities are viewed merely as one element in a long and wide narrative of repression under majority Bamar rule. Burma’s ethnic minority groups, which account for as much as 40 percent of the population, have been engaged in decades-long armed conflict with the military regime in their struggle for self-determination, recognition of ethnic rights, a federal government system, and equality.

Nay Lin Oo, a Mon human rights activist, recounts how his father fled to the jungle in 1962 when General Ne Win abolished the Mon People’s Front (MPF), arresting all Mon leaders and anyone who attempted to teach Mon language or culture. Forty-five years later, Naing Ngwe Theim was arrested during a mass detention of ethnic leaders as part of the crackdown following the September 2007 prodemocracy protests. “They colonized us by will, now they colonize us by ethnic and social [means],” Nay Lin Oo says, reflecting on the government’s layers of control.

Tomorrow, eleven parties will be fielding candidates to compete for the state’s 1.5 million eligible voters. The campaign period has been strenuous for the MNP candidates and party leadership, who have faced funding shortages, struggles with the Union Election Commission (UEC), and contention with the competing Mon party, the All Mon Region Democratic Party (AMDP). An attempted merger between the two parties broke down earlier this year after a leadership struggle, rued by many activists in light of the resulting vote dilution and confusion for voters. “We have a lot of choice but everyone is confused. They don’t know the difference, what the candidates stand for,” Joan Tha Man from Mon Progressive Youth said in reference to what he labeled the “two party problem.”

Naing Ngwe Thein has limited faith in the UEC, who he says “cheated” in the 2010 elections and remains a biased and ill-equipped institution. He reports that the final voter lists in Mon State are error-laden and inflated; MNP information officer Nai San Hlaing says his family of four has eight members showing up on the list. After the 2010 elections, 37 ethnic parties met with the UEC to lodge complaints that were never addressed. “We don’t trust them,” Naing Ngwe Thein says, “but we have to participate in the election anyhow.”

Distrust of the commission grew in September when voting was cancelled due to “security concerns” in 33 villages in Karen State, where the population of 20,000 is 80 percent Mon. Villagers in the area, which is under New Mon State Party (NMSP) control, sent a petition challenging the decision, viewed by many Mon leaders as a USDP tactic to disenfranchise ethnic voters. The Mon State police force has also recently announced that it will recruit Tatmadaw (Burmese military) officers to provide security at 67 polling stations across the state where they have identify risk of “sudden violence,” a potentially intimidating factor for villages where the Tatmadaw has been a longstanding aggressor.

For many in Moulmein, Sunday doesn’t warrant the buoyant optimism seen in other areas around Burma. “Even though there are a lot of us, I have not too much hope for the election,” Joan Tha Man says. Activists expressed fears about the high levels of apathy and confusion among Mon citizens, especially in rural areas, that may contribute to a low turnout. Even if Mon ethnic party candidates win across the board, they still face a centralized government, enshrined military power, and an immovable constitution. For ethnic parties, the fight is different than NLD’s climb to the top – it is about visibility and representation, regardless how shallow; about having a seat at the table; and about the process of attempting to insert a thin wedge of autonomous decision-making into an otherwise rigged system.

After Naing Ngwe Thein recounts the various dead-end efforts over the past few years to make changes from within parliament, I ask him why they continue to contest elections that offer little in winning. He answers in Mon, a language they fear is disappearing due to the government’s ban on ethnic languages in the state curriculum. “We are still suffering from what the government has done in the past,” he says. “So we have to compete.”

A Dark Spring

(Taunngyi) – In the last week of Burma’s national elections, President Thein Sein’s office began a state television campaign to justify his administration’s performance since taking office in March 2011. The four minute TV slot begins with ominously rising rock music and the words, ”With the taste of the spring at the time…but which the different flavor [sic],” and then opens a rapid fire series of images comparing Burma’s top-down, managed transition with graphic scenes of the Arab Spring and political instability in the Middle East.

From the large demonstrations in Cairo, to conflict in Libya and Syria, the video then cuts to images of Burmese tranquility, order, and progress: the president and senior ministers meeting people who greet them in adulation; pictures of peace talks, smiling babies, and clowns; the president meeting opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi and various world leaders; and the president holding a summit on economic reform.

The video cuts next to images of continued carnage in the Middle East, the Mediterranean boat people crisis, dead children on the shores of Turkey, and acts of terrorism and fighting. But then it returns to Burma with images of mosques, Hindu temples, Christian churches, and Buddhist pagodas, suggesting the presence of religious harmony and tolerance that in fact Thein Sein’s government has seriously fractured with its courting of anti-Muslim forces pushing an extremist religious agenda. Most telling is the final set of images and footage that show the Burmese military during the annual armed forces day parade, making clear to any viewer that it is the military that props up the civilian government and has defined the lines of the transition.

The video sparked outraged responses on Burmese social media. In fact, the response was similar to that which met an earlier Thein Sein video released in the starting days of the campaign in September. That video touted Thein Sein’s achievements and ended with a direct nod to rising religious ultra-nationalism by denying Rohingya Muslims were from Burma, and taking credit for the passing of the four discriminatory, rights abusing “race and religion laws” in August.

Any realistic assessment of the human rights condition in Burma could have shown scenes of this year’s Rohingya Muslim boat crisis, the squalid conditions in the internally displaced camps in Arakan State, civilians fleeing escalating fighting between the military and Shan rebels just this week, or the destructive war in Kachin State that started the year Thein Sein took office. The war with the Kachin has killed hundreds and seen over 130,000 people displaced, many of whom will either vote beside their squalid camps or will be denied the right to vote. That video could also display images of students being savagely beaten by police near Letpadan in March this year, or watching people being arrested for posting funny images of the military online.

The final line of President Thein Sein’s end of election campaign video sounds like an eerie, intimidating throwback to previous military governments when it proclaims, “Only when peace prevails will democracy be implemented.” Many people in Burma would reverse that formulation, and argue that only when genuine democracy is implemented will peace prevail in Burma. The elections tomorrow are another step in a long, arduous journey to achieve just that.

A Quarter Century

(Moulmein) – Thiri Mon sits at a student desk in a small schoolroom off Pabedan Road, a few blocks north of the Thanlwin riverbank. The room is filled with English textbooks and photographs from China, England, and northern Burma. She sips pomelo juice while talking about her students, her daughters, and her city – Moulmein, where she has lived for over 30 years. When I ask if she voted in the 1990 elections she nods, “Yes, of course. Around the corner from here. But that was a long time ago.”

The elections held on May 27, 1990 took place in a surprisingly free and fair environment, leading to a National League for Democracy (NLD) landslide with 80 percent of parliamentary seats. The military government responded by annulling the vote, placing Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest, and imprisoning dozens of opposition MPs. Scores fled across the Thai border in exile. Those that remained faced decades under the authoritarian military regime.

The upcoming vote will be the first widely-contested national elections since those held 25 years ago, but life in Burma is still filtered through 60 years of military rule and repression. Political parties’ organizational capacity is low, as is voter awareness.

Thiri Mon describes her concerns from the vantage of someone who has seen freedom given, then taken away. “People are excited for change, we all would like it. A leader having lots of followers is good, but leaders need to bring up more leaders. I am worried about the candidates. They are not politicians.”

She talks about seeing the opposition rallies in the streets, the supporters’ verve and excitement. “They want the NLD to win, but what happens afterward?” She is speaking carefully, with brief asides in Burmese to the three students who have arrived early for their afternoon class. “This is a worry of older people, maybe. Young ones, they say, ‘Yeah, change!’ They don’t know what to expect.” She pauses, then says, “I don’t know, maybe that is better.”

Burma Elections: Trouble in Kachin?

(Myitkyina) – The speeches are done, the songs have stopped. The election campaign has ended in Burma. The posters are gradually coming down, and supporters are putting away their party t-shirts, caps, and stickers for the day of silence on November 7 before polling starts early the next morning.

In Mytikyina in Kachin State, international election monitors are already arriving. But large portions of the state are inaccessible to foreigners because of ongoing armed conflict. It is local Burmese monitors, 284 of them, who are deploying in these sensitive areas.

Thomas Mung Dan of the Humanity Institute is poring over maps. He jabs at various corners where there are gaps. “It is the area they call ‘orange’ because of the conflict.” In some places, polling has already been canceled. In others, people will not be able to vote because there was no voter registration in rebel-held areas.

“We are worried because of security in some of these places,” he said. Other regions are simply too remote to be easily accessed. “There are no phones, no transport,” he said. Burmese groups will deploy local residents as observers. But to reach some of the polling booths in Chipwi and Tsawlaw, observers will have to travel through neighboring China.

Election monitors are already anticipating serious problems because of shortcomings during advance voting. The election commission permitted the old and the infirm to vote in advance, but didn’t seem to have set criteria on eligibility. Others decided to take advantage as well, to dodge the queue, get their day of rest, or attend church services because elections will be held on Sunday.

Advance voting has exposed some serious concerns. Despite efforts by the election commission, international experts, and Burmese civil society groups, voter education still leaves a lot to be desired. Many of the voters are confused by the ballot sheets – there are 93 parties in the running – and unable to properly identify and select their candidates. They are also bewildered by the fact that they have to select candidates for the national parliament as well as regional assemblies. “There will be a lot of invalid votes,” said Mung Dan. “People don’t know parties, candidates, whether they have to cast one vote, or two, or three.”

Representatives of the Union Election Commission (UEC) seemed unclear about their roles as well. Members of contesting parties and observers were invited to the advance polling. They milled around as voters stamped their ballot papers, undermining one of the most important principles of an election – a secret ballot. Some commission officials happily took pictures, unaware that this was forbidden. “There is much commitment to transparency, but this was perhaps a little too transparent,” Mung Dan said.

Of greatest concern is that in some cases the election commission failed to produce ballot boxes, meaning voters had to drop their ballots into an open sack. This raises the possibility, even likelihood, of ballot stuffing. Election commission officials excused this lapse, explaining that some of their staff did not quite know how to use and seal the ballot boxes. “These are serious problems,” sighed Mung Dan. “Is it because of their lack of skill, or an intentional mistake? I don’t know.”

Burma Elections: Magic in Pyin Oo Lwin

(Pyin Oo Lwin) – Pyin Oo Lwin Township, in the northeast corner of Mandalay Region, is an important center for Burma’s armed forces and police. Multiple walled compounds there contain national-level military, police, and other academies, where senior officers train their subordinates and successors. A local historian says military men and women and their dependents comprise 20,000 of the Pyin Oo Lwin’s total population of around 180,000 and points out that the army considers the township a strategic gateway to areas further north and east where it has fought with ethnic minority insurgents for decades.

Historically, it has been a crossroads for trade, which has helped give it a multicultural character, one aspect of which is the presence of what a local Muslim community leader estimates is an Islamic population of 10,000 – composed of various ethnicities who attend perhaps a dozen small mosques in the township. There are also a number of Christians and one very large church. However, the majority of the population is Buddhist, and one senior Buddhist abbot estimates there are approximately 2,000 monks and nuns, and hundreds of novices, in two major pagodas and “dozens and dozens” of smaller pagodas and monasteries.

Candidates and other officials of the leading opposition party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), say the party campaign activities in Pyin Oo Lwin have not been interfered with. Speaking on the last day of campaigning at the township party headquarters, across from one of Pyin Oo Lwin’s military academies, those party officials recounted that there had been two major rallies to mark visits by high-ranking NLD delegations from the party headquarters in Rangoon, numerous smaller gatherings, some door-to-door efforts to distribute NLD handbills in party-friendly neighbourhoods, and free roadside distributions and sales from stalls of NLD headbands, face-stickers, and flags.

They added that there have been no significant attempts by state security forces, government officials, pro-government parties, or their political allies to deter or disrupt such campaign activities. At the same time, as one key NLD organizer on the township committee put it, there has been a “lack of resistance” within the party and among its supporters. Asked to explain, he said that fear of the government’s military potential in Pyin Oo Lwin has made people “reluctant to be as active and vocal as they wanted to be.”

The major NLD complaint heard locally is what several of them called as “voter roll magic,” by which they allege names have “magically” appeared and disappeared from the voter list. As in other places in Burma, these local NLD officials suspect government-friendly local election sub-commissions are finagling to exclude NLD supporters and illicitly include NLD opponents, above all members of the Union Solidarity Development Party (USDP).

The NLD claims local USDP officials make no secret of the party’s links to military power in the township, nor of its sympathy for a “racial and religious ultra-nationalism” that the NLD accuses the army of attempting to promote. To back the allegation of electoral fraud, NLD activists produced originals of the flimsy white bits of paper used as voter identification that the activists claimed were in the names of dead people or people who otherwise do not exist.

They also made available for interview NLD supporters who stated that although they had voted in several previous elections in Pyin Oo Lwin, their names had mysteriously disappeared from first version of the voter roll made public in the township, and that despite their requests had not been restored in the second version of the list. Many NLD officials and supporters declared that the fact that two days before voting, the sub-commission had still failed to make public on schedule a third, final official list was intensifying fear of “more conjuring” and “general confusion” among would-be voters. They argued this was having a demobilizing effect on parts of the pro-NLD electorate.

They also expressed concern about the possible demoralizing impact of fears of post-election violence should the NLD win too many votes, precipitating a possibly shocked reaction from the military, the USDP, and what they called “sorcerers.” They explained that by this they meant, among others, emergent elements within the Pyin Oo Lwin Buddhist monkhood of the Ma Ba Tha (the Association to Protect Race and Religion), a chief proponent of racial and religious ultra-nationalism, which targets Muslims in particular as outside and enemies of the nation. They said they were alarmed by a recent Ma Ba Tha movement leadership statement characterizing anyone opposing Ma Ba Tha activities as “a destroyer” of the Burmese nation.

In separate interviews on November 6, several senior Buddhist monks in Pyin Oo Lwin denounced Ma Ba Tha, asserting it was born out of what they claimed has been a largely failed attempt by the military and USDP to co-opt Burmese Buddhism as a “tool of the state they control.” By their accounts, this effort has been widely resisted within a Buddhist monkhood that they said has historically stood morally with Buddhists and others against authoritarian and divisive misdeeds in Burma. The result, they maintained, was not co-optation, but creation of Ma Ba Tha as an extremist fringe splinter within Buddhism.

The Pyin Oo Lwin monks interviewed proudly stated that resistance to its “unethical political tactics” has been particularly effective in their township, with the overwhelmingly majority of Pyin Oo Lwin monks and other Buddhists continuing to favor interreligious, interethnic tolerance, understanding, and cooperation in the interests of the population as a whole. Muslim community leaders in Pyin Oo Lwin corroborated this, as did several local lay Buddhist writers and artists. Still, one of the Muslim dignitaries asked not only that he not be named, but that no photograph of his place of worship be taken, because “it might end up on Facebook, and maybe one day Ma Ba Tha will make trouble.”

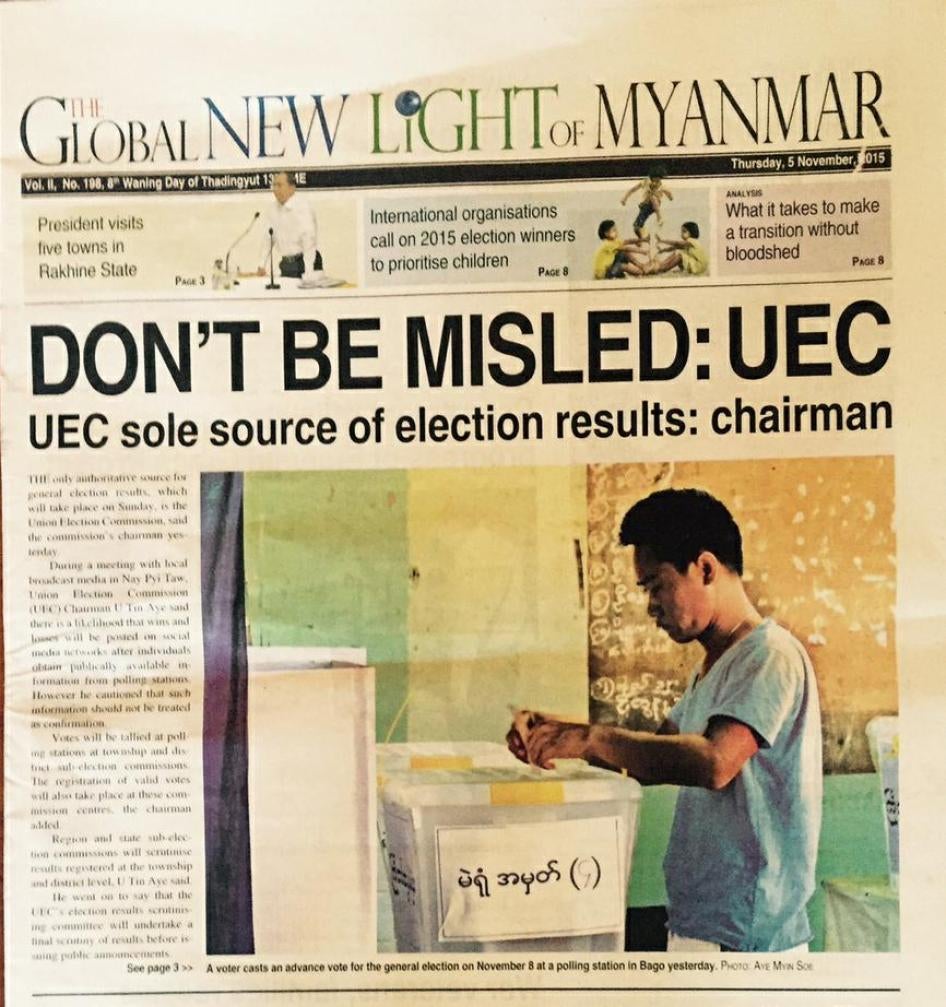

Burma Elections: Biased Commission Undermines Polls

(Myitkyina) – "We have been very concerned by the lack of enthusiasm on the part of the UEC [Union Election Commission] to hold free and fair elections," National League for Democracy (NLD) leader Aung San Suu Kyi said during her final press conference before Burma goes to the polls on November 8. "We have repeatedly made complaints about the way in which some parties and individuals have been breaking the rules and regulations laid down by the election commission, but very little action has been taken."

Aung San Suu Kyi was alluding to the obvious bias in the UEC, which runs the election at the national and local levels. On Thursday the UEC issued a statement decrying the criticism it has been subjected to for the election’s shortcomings, particularly by the NLD.

It is hardly surprising that a commission led and staffed by former military officers would not be impartial. The chairman, U Tin Aye, is a former army general and member of parliament from the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP). In June he made his views clear: “As a chairman, I am not supposed to have attachment to the party…. I have an attachment, but I don’t put it at the forefront of my mind…. I want the USDP to win, but to win fairly, not by cheating.”

While promising that the 2015 elections would be free and fair, he said they would be conducted in “disciplined democracy style,” using rhetoric closely associated with past Burmese military governments. On March 27, during the annual Armed Forces Day parade in the capital, Naypyidaw, Tin Aye wore his military uniform during the ceremony, saying: “I would give up my life to wear my uniform. I wear it because I want to. That’s why I wear it even if I have to quit [the UEC] because of that. But there is no law saying I should resign for wearing [my] uniform.”

Other parties are also worried about UEC bias. The commission has rejected nearly a hundred candidate applications, most of them by Muslims, because the authorities now claim that their parents were not recognized as citizens at the time of the candidate’s birth. This is odd, as some had been elected in previous elections. For instance, the UEC rejected the candidacy of Shwe Maung, a Rohingya lawmaker from the ruling USDP. He had planned to run as an independent candidate in this election.

Of the 6,074 approved candidates, 5,130 are Buddhist, 903 Christian and just 28, or 0.5 percent, are Muslim, a sliver of the the percentage of Muslims in the general population . This is only partly due to discriminatory decisions by the UEC. The main parties have also shown extreme bias: to stave off criticism from the racist and Buddhist nationalist Ma Ba Tha, which campaigns against Muslim citizenship and in favor of legal discrimination against Muslims in Burma, both the NLD and the USDP have no Muslim candidates.

Despite a massive effort supported by international organizations, there are also persistent concerns about accuracy of voter lists compiled by the UEC. Some 6.5 million people out of a total of 32 million have submitted corrections to the initial list. Aung San Su Kyi mentioned at her press conference that the UEC had vouched for only 30 percent of the voter list. Here in Mytikyina in Kachin State, one man told me that his details are still not correct despite numerous attempts to correct them. “There may be many more problems,” he said.

UEC bias may also show up in how complaints are resolved. Election procedures still lack appropriate mechanisms for addressing complaints. Complaints will be brought before ad hoc tribunals set up under the UEC, with a panel of three arbiters comprised of election commissioners. But in violation of international norms, complainants can only appeal a tribunal’s final decision to the UEC, whose ruling is final and made without judicial oversight. As in other countries, such as Cambodia, where the post-election period has been extremely contentious because of the lack of impartiality of the national election commission, this is where things could unravel. Aung San Suu Kyi said she was worried whether election officials will adequately respond to allegations of irregularities. “If it looks too suspicious then I think we will have to make a fuss about it,” she said.

The Burmese people appear enthusiastic about the election, but also extremely nervous. The UEC chairman, however, is asking voters to believe in the process, to trust only results announced by the commission. That is easier said than done when the request comes from a man who has made it clear who he wants to win.