Summary

An increase in school enrolments from 40 to 60 percent is applauded as a success, not recorded as a violation of the right to education of the 40 percent of children who remain excluded from school.

-Katarina Tomasevski, former United Nations special rapporteur on the right to education, 2006

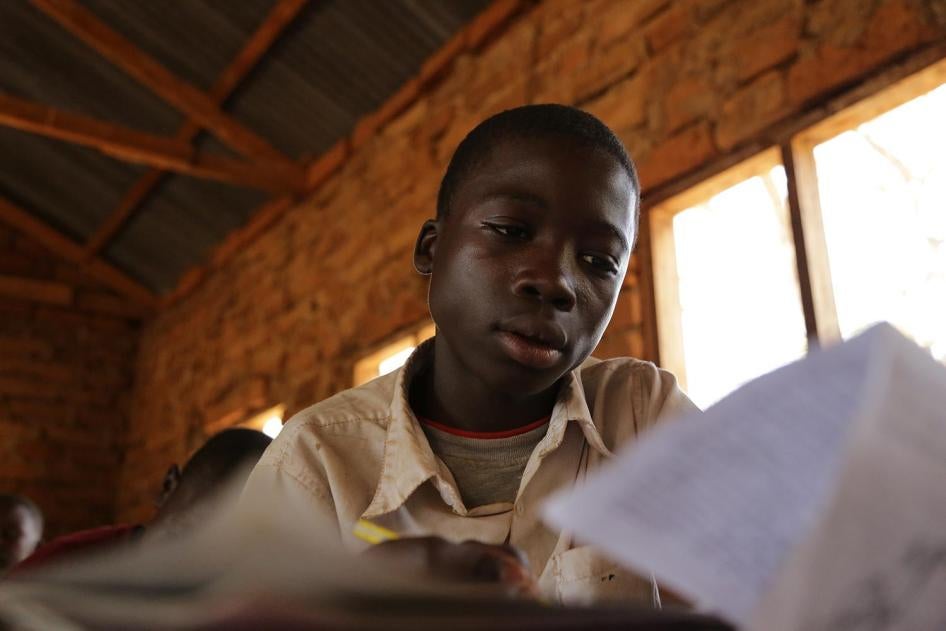

Across the world, more than 120 million children and adolescents are absent from class.

In recent years, many countries have been part of international and regional political drives to ensure that all children have access and complete education in the countries that lag behind the most. Such efforts have had some success, with tens of millions entering primary education, and more girls staying in school and pursuing secondary education, improving gender parity in more countries.

Yet despite these and other advances, warnings sounded by the UN and global policy experts indicate that the global progress in education has “left behind” millions of children and young people. More children and adolescents are at risk of dropping out of school, and many are at school facing unsuitable learning conditions.

Behind this failure stands governments, which bear responsibility for ensuring that no child or young person is without education, and lack of focus—both in implementation and in content—in development agendas on governments’ human rights obligations.

This has resulted in an “education deficit”—a shortfall between the educational reality that children experience around the world and what governments have promised and committed to through human rights treaties. This not only undermines the fundamental human right to education, but has real and dire consequences for global development, and entire generations of children.

The benefits of education to both children and broader society could not be clearer. Education can break generational cycles of poverty by enabling children to gain the life skills and knowledge needed to cope with today’s challenges. Education is strongly linked to concrete improvements in health and nutrition, improving children’s very chances for survival. Education empowers children to be full and active participants in society, able to exercise their rights and engage in civil and political life. Education is also a powerful protection factor: children who are in school are less likely to come into conflict with the law and much less vulnerable to rampant forms of child exploitation, including child labor, trafficking, and recruitment into armed groups and forces.

196 member states have adopted legal obligations towards all children in their territories, and countries that ratify specific international and regional conventions are legally bound to protect the right to education and to follow detailed parameters as to how to do so.

Based on research in over 40 countries, this report looks at the key barriers that threaten the right to education today, and the key ways that governments are failing to deliver on core aspects of their right to education obligations. These include ensuring that primary school education is free and compulsory and that secondary education is progressively free and accessible to all children; reducing costs related to education, such as transport; ensuring that schools are free of discrimination, including based on gender, race, and disability; and ensuring schools are free of violence and sexual abuse. It also looks at the main violations and abuses keeping children out of school, including those that occur in global crises, armed conflict—particularly when education is attacked by armed groups,—and forced displacement.

This report finds that many of the same governments that have signed on to development agendas and form part of global partnerships—including among the 16 champion countries that UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon appointed in September 2012 to “lead by example” to promote education globally—are those that are also failing many of their school-aged children.

In the new era of sustainable development, where all countries are expected to implement a universal development agenda, all governments need to be held to account for ongoing human rights abuses affecting a significant part of their young population, as well as a failure to provide adequate or timely protections to which children are entitled under the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The Education Deficit in Numbers

|

Weak government monitoring mechanisms, lack of zero-discrimination policies, lack of accountability for children who drop out of education, and unchecked power wielded by school officials as to who goes to school and who stays out are among the factors contributing to governments’ failures to ensure the right to quality education for children who have traditionally endured discrimination.

Moreover, a global push for universal primary education through development agendas has, in some cases, unintentionally led to less political and financial attention being paid to the right to secondary education, resulting in millions of adolescents being unable to continue their studies. As this report shows, these are children and adolescents who are at high risk of exploitation for child labor, early marriage or teenage pregnancy, as well as girls and young people with disabilities whose chance of receiving secondary education is already limited by systemic and discriminatory barriers.

Ending the Education Deficit

First and foremost, ending the education deficit means ensuring every child has a quality primary and secondary education—without the financial and systemic obstacles many face today—and that relevant governments tackle the numerous violations, abuses, or situations that keep children out of school. This in turn depends on political will to institute strong governance systems, including via the judiciary, to uphold and fulfill the right to education.

It also depends on international actors who set policy globally and engage in education through technical and international cooperation.

Donors, multilateral financial bodies—including the World Bank and the Global Partnership for Education,—and international agencies that help governments to implement ambitious education plans should recall their responsibilities to uphold human rights standards and not compromise on key abuses that leave children out of school. This is particularly the case with international actors working with governments unwilling to provide greater protections to minorities, refugees, or persons who have been made stateless; or in cases where governments do not allocate sufficient resources to underserved areas or particular groups of children, particularly children with disabilities.

The UN should continue to hold all governments to account for violations of the right to education. Globally, any champion country or government representative appointed to lead on global education issues must first abide by international human rights standards for all children in its territories and abroad, in cases where they also play a key role as donors, and be open to scrutiny by its own national civil society, as well as UN bodies reviewing its performance.

Key Recommendations

All governments should:

- Produce and publish reliable and disaggregated primary and secondary enrollment, attendance, and completion statistics by age, gender, disability at a minimum, as well as ethnicity, religion, language, and other categories, where minorities have been traditionally discriminated against.

- Ensure national legislation includes protection for the right to education, including secondary education, consistent with international law.

- Take steps, including through policy and monitoring, to ensure nondiscrimination, and guarantee the reasonable accommodation of children with disabilities.

- Ensure primary education is free and ensure indirect costs do not become a barrier to access. Promptly investigate cases of children being denied access to school or being expelled from school due to an inability to pay fees or for school supplies, including uniforms.

- Ensure national legislation protects the compulsory nature of primary education. Adopt mechanisms to monitor the enforcement of compulsory education at a local level, including actions by school officials, parents, or community leaders which could jeopardize children’s access to education.

- Make time-bound plans, including with international assistance, to ensure secondary education is free.

- Outlaw all forms of corporal punishment in schools and introduce stronger guidelines to stop bullying in schools.

- Strengthen child protection mechanisms in schools and local communities to ensure any allegations of sexual abuse, corporal punishment, or discrimination against students are promptly investigated, redressed, or prosecuted.

- Make comprehensive sex education part of the school curriculum, ensure that teachers are trained in its content, and allocate time to teach it.

- Increase the legal age of marriage to 18 for both men and women and monitor local compliance with this age requirement by judges, local government officials, or traditional leaders who are involved in performing or registering marriages, and enforcement by police of laws criminalizing child marriage.

- Ensure the provision of education in crises and displacement, and adopt special measures to ensure children can continue to go to school in highly insecure areas, including by reducing the distance to school, offering distance learning programs, and setting up protective spaces for girls and teachers.

- Endorse the Safe Schools Declaration and implement the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict.

- Ratify key treaties, including the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Convention Against Discrimination in Education, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and the International Labour Organization 1973 Minimum Age Convention (No. 138) and 1999 Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention (No. 182).

I. International Human Rights Standards

Right to Education

Education is a basic right enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)—the most widely ratified human rights treaty in history, ratified by all states except the United States—as well as in many other UN and regional treaties.[1] International human rights law makes clear that all children have a right to free, compulsory, primary education, free from discrimination.[2] State Parties should also ensure different forms of secondary education are available and accessible to every child, and take appropriate measures, such as the progressive introduction of free education[3] and offering financial assistance in case of need.[4]

State parties to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) must submit an action plan on how they will guarantee free and compulsory primary education to all children within two years of ratifying this treaty.[5]

Right to Access Inclusive, Quality Education

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) promotes “the goal of full inclusion”[6] while at the same time considering “the best interests of the child.”[7] Children with disabilities should be guaranteed equality in the entire process of their education.[8] The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the United Nations human rights agency, states that:

The right of persons with disabilities to receive education in mainstream schools is included in article 24 (2) (a), which states that no student can be rejected from general education on the basis of disability. As an anti-discrimination measure, the “no-rejection clause” has immediate effect and is reinforced by reasonable accommodation… forbidding the denial of admission into mainstream schools and guaranteeing continuity in education. Impairment based assessment to assign schools should be discontinued …. The legal framework for education should require every measure possible to avoid exclusion.[9]

International law provides that persons with disabilities should access inclusive education on “an equal basis with others in the communities where they live,” and governments must provide reasonable accommodation of the individual’s requirements, as well as “effective individualized support measures in environments that maximize academic and social development.”[10] The government must ensure that children are not excluded from the education system on the basis of their disability.[11]

Duty to Ensure Reasonable Accommodation

The CRPD places an onus on governments to ensure that “reasonable accommodation of the individual’s requirements is provided” and that “persons with disabilities receive the support required, within the general education system, to facilitate their effective education.”[12]

The CRPD defines “reasonable accommodation” as any “means necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments not imposing a disproportionate or undue burden, where needed in a particular case, to ensure to persons with disabilities the enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with other of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.”[13]

According to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, a government’s duty to provide reasonable accommodation is “enforceable from the moment an individual with an impairment needs it in a given situation … in order to enjoy her or his rights on an equal basis in a particular context.”[14] In assessing “available resources” to guarantee “reasonable accommodation,” governments should recognize that inclusive education is a necessary investment in education systems and does not have to be costly or involve extensive changes to infrastructure.[15]

Quality of Education

According to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, “Every child has the right to receive an education of good quality which in turn requires a focus on the quality of the learning environment, of teaching and learning processes and materials, and of learning outputs.”[16]

Under the Convention Against Discrimination in Education, states must “ensure that the standards of education are equivalent in all public educational institutions of the same level, and that the conditions relating to the quality of the education provided are also equivalent.”[17]

The CRPD includes the right to access quality learning, which focuses and builds children’s abilities, and for children with disabilities to be provided with the level of support and effective individualized measures required to “facilitate their effective education.”[18]

Progressive Realization of the Right to Education

Education, an economic, social, and cultural right, entails state obligations of both an immediate and progressive kind. This set of rights is subject to progressive realization, in recognition of the fact that states require sufficient resources and time to respect, protect, and fulfill these rights. However, according to the Committee for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, steps towards the Covenant’s goals must be taken “within a reasonably short time after the Covenant’s entry into force” and “such steps should be deliberate, concrete and targeted as clearly as possible towards meeting the obligations.” The Committee has also stressed that the Covenant imposes an obligation to “move as expeditiously and effectively as possible towards that goal.” [19]

The OHCHR provides further clarification: “The treaties impose an immediate obligation to take appropriate steps towards the full realization of economic, social and cultural rights. A lack of resources, or periods of economic crisis, cannot justify inaction, retrogression in implementation or indefinite postponement of measures to implement these rights. States must demonstrate that they are making every effort to improve the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights, even when resources are scarce.”[20]

International Cooperation and Assistance

The CRC and ICESCR refer to the need for international assistance and cooperation to support the progressive realization of human rights.[21]

According to the OHCHR, “all Member States of the United Nations and United Nations agencies should respect and observe human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without discrimination in their international cooperation ... They should also respect the human rights obligations that the recipient country has accepted under international as well as national law. They should ensure that their cooperation will not undermine the recipient country’s efforts to realize human rights, including economic, social and cultural rights, and ideally facilitate and support such efforts. [22]

II. Global Education Efforts

In September 2015, all United Nations member states agreed to work together to “ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning” by 2030 as part of the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).[23] This was the latest international initiative aimed at tackling inequality in, and lack of access to, education.

In 2000, education ministers from most of United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)’s member states had gathered in Dakar, Senegal, to adopt the Education for All Framework (EFA) with six comprehensive goals overseen by UNESCO, including goals to reach gender parity in education, and increase youth literacy rates.[24] Global leaders gave themselves 15 years to accomplish these fundamental goals.[25]

That same year, all UN member states signed onto the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which aimed, among other things, to ensure all children complete primary education and that an equal number of girls and boys remain in school.[26]

Five years after that, in 2005, the international community acknowledged the enormous barriers children—including the 100 million out of school—faced receiving an education, including lack of quality education, school fees and related expenses, discrimination, and widespread violence in schools.[27] Certain at-risk populations, such as children with disabilities, were not even mentioned in the MDGs, resulting in a lack of targeted efforts and limited or no data on their enrollment or access to education.

In 2010, the initial emphasis on progress in education faltered, as domestic investment and multilateral and bilateral donor funding dedicated to education decreased dramatically as donors reduced their global aid budgets or diverted existing funds to other sectors, dealing a setback to ensuring children receive primary and secondary education.[28]

In an effort to revitalize global support for education, in 2012 UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon launched the UN’s Global Education First Initiative and appointed 16 champion countries to help him give a “big push” to the global movement for education by 2015 and beyond.” [29] He called on world leaders and all involved in education to join the initiative and “fulfil the promise to make quality education available to all children, young people and adults.”[30]

In 2015, in view of the continued dwindling of global aid to education, 21 global leaders, co-convened by the Norwegian Prime Minister and the Presidents of Chile, Indonesia, and Malawi, were appointed to an International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity, “to reverse the lack of financing for education around the world.”[31] In 2016, UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report warned that if countries were serious about implementing the SDG on education, aid had to increase at least six times to cover the annual financing gap of US$39 billion.[32]

III. Violations and Barriers Affecting the Right to Education

This serves as a grim reminder that the world has yet to fulfil its original promise to provide every children with a primary education by 2015.

— UNESCO, Global Education Monitoring Report, 2015

Millions of children have no access to education, or in some cases, interrupt their education, because of ongoing human rights abuses, and governments’ failures to provide adequate protections they are entitled to under the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) or to counter abuses perpetrated by state and non-state actors.

All children have a right to go to school, to have equal access to education at all levels, and to be guaranteed a quality education. While many governments have focused on legislating the right to primary education, the right to secondary education—both lower and higher—remains unprotected and unfulfilled in many countries.[33]

Guaranteeing equal access to schools to all children satisfies one basic component of the right to education. However, without a quality education, children may leave schools unmotivated, illiterate, and unprepared for life after education. The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child underscores that “the key goal of education is the development of the individual child’s personality, talents and abilities, in recognition of the fact that every child has unique characteristics, interests, abilities, and learning needs.” Governments need to ensure that “no child leaves school without being equipped to face the challenges that he or she can expect to be confronted with in life.”[34]

To make this happen, governments should put in place mechanisms to ensure education is widely available to all children on an equal and inclusive basis. As Kofi Annan, then-UN Secretary-General said in 2000: “More than buildings are required, however. Schools must be accessible, have qualified teachers and offer such amenities as textbooks and supplies for the poor.”[35]

The following sections outline numerous human rights violations and key barriers to children being able to claim their right to education.

The Cost of Going to School

Most [students at] mainstream schools don’t have to pay. But for us, we have to pay school fees. Lots of parents who have children with disabilities can’t work—we have to take care of them 24 hours. Schools write to ask why we haven’t paid but they don’t understand our situation. The schools are away from our locations. All the [care dependency] grant is going towards the fees, so there’s no money for transport… and our children have equal rights?

—Father of an eight-year-old boy with autism, Johannesburg, October 2014

The Universal Declaration on Human Rights of 1948 includes the right to free education “in the elementary and fundamental stages,” and reinforces the compulsory nature of elementary education.[36]

Since then, most governments have accepted, through their ratification of various human rights treaties, a legal obligation to ensure primary education is free and compulsory, and to gradually make secondary education free and available to all.[37] According to the World Policy Analysis Center, a global social protection research and data initiative, only six countries in the world charge formal tuition fees at primary level, 22 charge fees in lower secondary, and 35 in upper secondary.[38]

Fees in Primary Schools

While many governments have adopted policy measures to expand free primary education to all children,[39] some have not translated their international obligations into national legislation, which binds governments to provide free primary education to all children in their territories.[40] The lack of political will to move towards fully “free” education, and to oversee an adequate implementation at the local level, has a very significant impact on children from the poorest families or children who belong to traditionally excluded groups.[41]

|

South Africa’s constitutional protections of the right to basic education have long been used as a progressive model for other constitutions.[42] Although the government has taken numerous steps to remove financial barriers for the poorest students, primary and secondary education are not automatically free in constitutional obligations or education legislation.[43] While the majority of the school population can access “no fee schools” or fee waivers, Human Rights Watch research found that many thousands of children with disabilities who go to public schools are expected to pay significantly high school fees and pay for other conditional expenses which children without disabilities do not pay in public schools. This is a discriminatory practice.[44] |

Fees in Secondary Schools

I passed [the exam] to go to secondary school. My mother did not have money to send me to secondary school. She then forced me to get married saying it was improper for me to stay at home.

—Amber T. (pseudonym), 18, married at 15, Kahama, Tanzania, April 2014

Governments have an international obligation to make secondary education accessible and available to all children, and to progressively make secondary education free or take measures to fund students requiring financial assistance.[45] According to UNESCO, a growing number of young adolescents are also out of school, with the global total reaching almost 65 million in 2013. Adolescents of lower secondary school age—ranging from 12 to16 years—are almost twice as likely to be out of school as primary school-age children, with 1 out of 6 not enrolled.[46]

Yet, many governments have struggled to expand the availability of secondary education in line with demand from primary school graduates, and have not built enough infrastructure to cater to the increased demand for further levels of education.[47] In countries like Tanzania or Bangladesh, Human Rights Watch has found that access to secondary education is often limited through national assessments in the form of primary school exams, which filter the number of students passing through to secondary education, and school fees.[48]

Families often incur further financial obligations when their children proceed on to secondary education. Limited availability of secondary schools in rural or remote areas means students may have to pay to travel very long distances on a daily basis or rent rooms or pay for boarding facilities in bigger towns.[49]

Parents may also prevent girls from accessing further levels of education due to costs and safety concerns when provision of education is limited. Human Rights Watch has found a strong correlation between child rights violations, such as the early marriage of girls under the age of 18, or the worst forms of child labor, and the expenses associated with secondary education.[50]

|

Bangladesh has the highest rate of child marriage of girls under the age of 15 in the world, with 29 percent of girls in Bangladesh married before age 15, according to the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF).[51] Successive inaction by the central government and complicity by local officials allows child marriage, including of very young girls, to continue unchecked, while Bangladesh’s high vulnerability to natural disasters puts more girls at risk as their families are pushed into the poverty that helps drive decisions to have girls married. Additionally, despite the government’s pledge to end child marriage by 2041, Bangladesh’s Prime Minister attempted to lower the age of marriage for girls from 18 to 16 years old.[52] Many girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch dropped out of secondary school because of fees and associated expenses and married at a young age. The government’s nationwide female stipend program for primary and secondary education to further girls’ education has resulted in the gross enrollment rate of girls at secondary level rising to 53 percent. However, even the smallest associated costs in secondary education, including exam fees and private coaching, mean children from many of the poor families cannot attend school and are vulnerable to early marriage.[53] Khadija, 35, has 4 children, and decided to take her 13-year-old daughter out of school: “I can’t pay so she will have to quit.” Her family lives in two rooms and survives through Khadija’s husband doing agricultural work and any other work they can find. “She studied until class five, but now she needs to go to high school. The high school charges 2,500 taka [$32] in registration fees. I would also have to pay for private tutoring and books.” [54] |

Indirect Costs and Expenses

There are a lot of parents who would send their children to school if it weren’t for these costs…there are a lot of people who can’t even afford a 10 taka [$0.13] exam fee.

-Nongovernmental organization worker in Laxmipur, Bangladesh, October 2014

The removal of formal school fees significantly contributes to opening the school doors to the majority of children. However, the associated costs of education in primary and secondary schools result in direct financial barriers—such as transport costs and payments for books, uniforms, stationery and equipment, exam fees or parent teacher association fees, and personal assistants (for children with disabilities).[55] Indirect costs and expenses tend to be much higher than school fees, and “constitute disincentives to the enjoyment of the right and may jeopardize its realization.”[56]

Although the impact of these additional financial barriers are often blamed on poverty, governments have to fulfill an “unequivocal requirement” to ensure education is “free of charge” and to take measures to eliminate financial barriers.[57] Such measures should begin at the school level, where school officials and teachers collect additional fees and in many cases, punish or stop children from attending school who have not paid additional charges.

In Bangladesh, Morocco, and Tanzania, Human Rights Watch found that some indirect costs exclude poor children as a result of questionable practices by teachers. Abuses where teachers do not teach students compulsory subjects during class hours, but instead charge students and their families to teach these classes outside of school, remains widespread and impacts on children’s equal access to the same standard of education. [58]

Endah, a child domestic worker in Indonesia, explained to Human Rights Watch why she started work at age 15:

I couldn't continue school so I decided to get work. [My last year of school was] the first semester of the first year of junior high. I really wanted to continue studying, but I really didn't have the money. [The school fee] was 15,000 rupiah [$1.50] per month. But what I really couldn't afford was the 'building fee' and the uniform. It was 500,000 rupiah [$50] for the building fee and uniform…. Then each semester we had to buy books.[59]

|

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Human Rights Watch found that many children living and begging on the streets may be driven by their parents’ or guardians’ inability to pay school fees and other related costs of primary education. For example, Peter, in Lubumbashi, told us: I had to leave school after I finished the third grade. My parents could no longer afford the fees, so I started coming to the streets to look for something to do. Life here on the streets is hard, there is never enough to eat, and I am hungry. I would like to return to school and continue my studies.[60] |

These additional—and often unofficial but obligatory—expenses lead to inconsistent attendance of children and eventual drop-outs, particularly of girls and children with disabilities, and particularly impact on secondary school-going students who often pay higher fees and expenses.[61] In many cases, they become disincentives for poorer families who are no longer able to pay for their children’s expenses.

Parents or guardians may consider forcing children into harmful labor practices or early marriage to offset the costs of their education.[62] In Nepal, Ram Kumari Chaudhary, 16, studied to class six and married at age 14. She told Human Rights Watch: “My father stopped my schooling because he could not afford my fees, stationery, and uniform.”[63]

Recommendations

|

Discrimination in Schools

The teacher tells us to sit on the other side. If we sit with the others, she scolds us and asks us to sit separately… The teacher doesn’t sit with us because she says ‘we’re dirty.’ The other children also call us dirty everyday so sometimes we get angry and hit them.

—Pankaj (pseudonym), a child belonging to the Ghasiya tribal community, Uttar Pradesh, India, April 2013

Me and my cousin are the only two Syrians in the class. The rest of the students have ‘ganged up’ on us and are saying we speak a lot, that we misbehave. The teacher sent us to the back of the class. All teachers treat me badly because I’m Syrian. When one of the teachers asks a Jordanian girl and she answers the question then the teacher says ‘Bravo!’ When I answer, I get nothing. Once, going up the stairs with a Jordanian girl, I was told off and asked to go back to the line and wait until everybody went off.

—Mariam (pseudonym), 11, Al-Zarqa, Jordan, October 2015

Globally branded as children who have been “left behind”[64] or “the hardest to reach,”[65] many children have been consistently denied an education because of pervasive discriminatory beliefs or practices. On every continent, children suffer direct and indirect discrimination based on their gender, race, ethnicity, disability, religion, health status, or sexual orientation—or a combination of all—on a daily basis.[66] Many of these children first face the harsh realities of the outside world when they reach school where looking, acting, or feeling different often means ridicule, harassment, and at times, abuse at the hands of classmates, teachers, and others in schools.

According to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights—an independent body of experts overseeing the human rights treaty applicable to this set of rights, including education—discrimination constitutes “any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference or other differential treatment that is directly or indirectly based on the prohibited grounds of discriminationand which has the intention or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise [of rights] on an equal footing.”[67]

UNESCO’s Convention against Discrimination in Education—ratified by over 100 countries—also provides strong obligations on governments to eliminate any form of discrimination, whether in law, policy, or practice, which could affect the realization of the right to education. Under the Convention, states must “ensure that the standards of education are equivalent in all public educational institutions of the same level, and that the conditions relating to the quality of the education provided are also equivalent.”[68]

In addition to removing any forms of direct discrimination against students, governments should also ensure indirect discrimination does not occur as a result of laws, policies, or practices which may have the effect of disproportionately impacting on the right to education of children who require further accommodation, or whose circumstances may not be the same as those of the majority school population.[69] This is particularly the case with children with disabilities globally, or children belonging to minorities, such as the Roma, who may be placed in segregated or specialized schools in countries like the Czech Republic or Bosnia and Herzegovina, or many Kurdish children who are blocked from learning in their mother tongue in Turkey.[70]

Despite the numerous specific commitments to ensure that boys and girls have an equal right to education, adopted or endorsed by governments through special global initiatives, girls continue to face unique gender-specific barriers.[71] These will be outlined in a separate section.

Children Belonging to Ethnic, Religious or Language Minorities

The lack of acknowledgment of or dedicated action to remove direct or indirect forms of discrimination experienced by particular groups of children from minority groups continues to affect access to education for millions of children.

Some government continue to enforce discriminatory policies within their education systems.[72] These policies often relate to the prohibition of ethnic or cultural practices or languages, or may lead to the separation of children into different education systems, according to their ethnicity, race, or belief.

In a number of cases, persistent discrimination in schools—by school officials or teachers—may lead to drop-outs or lower school performance. In Nepal, for example, Human Rights Watch found that teachers adhere to social or cultural traditions which perpetuate discrimination in classrooms. Sunita married a classmate of a different caste at the age of 15. They decided to elope prompted by the harassment they faced in school. “The teachers would call me out of class and say, ‘He’s lower caste—you shouldn’t talk with him or be seen with him,’” Sunita said. “They used to beat me with sticks and pull me out of morning assembly and beat me in front of my friends. They said, ‘We’re doing it for her own good because she’s going around with a lower class boy.’”[73]

|

In 2001, Human Rights Watch found that in Israel, Palestinian Arab and Bedouin children, as well as Palestinian children in East Jerusalem, faced discriminatory access to quality education relative to Jewish Israeli children.[74] Even today, schools predominantly catering to Palestinian Arab and Bedouin children receive less funding, and are often overcrowded, understaffed, and sometimes unavailable.[75] Palestinian children in East Jerusalem suffer through grave shortage of classrooms and adequate school infrastructure, and are subjected to security barriers and checkpoints. In 2011, Israel’s Supreme Court ruled that a shortage of quality constituted a violation of the constitutional right to education for students in East Jerusalem.[76] |

***

|

In India, the government adopted the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act in 2009.[77] The Act guarantees free and compulsory education to all children aged 6 to 14, and makes it mandatory for government schools to provide free books and uniforms in government schools, while private schools are required to provide at least 25 percent free seats for those from weaker sections and disadvantaged groups.[78] However, discrimination against children from economically and socially marginalized communities, such as the so-called lower castes, tribal groups, and Muslims, by school authorities plays a significant part in children’s irregular attendance and low retention rates. Human Rights Watch research shows how teachers ask Dalit (formerly known as “untouchables”) children to sit separately in classrooms, or to wait for their free school lunches only after all the other students have had theirs. Teachers often continue to make insulting remarks about Muslim and tribal students,[79] and Human Rights Watch found that village authorities would make efforts to encourage parents to send their girls to school when they were kept away by their families.[80] |

Children with Disabilities

We tried to put him in a [mainstream] school but they said they couldn’t put him in that school because he has disabilities. The school said that he was naughty. Because of Down syndrome he isn’t like other children so they [said they] can’t teach him.

—Thandi, mother of an 8-year-old boy with Down Syndrome, South Africa, November 2014

Subjects such as physics and chemistry were missing. When we asked to study more things, the staff members cited our diagnosis: profound mental retardation. We were not thinking about our diagnosis. We just wanted to learn something new.

—Anton K. (pseudonym), 21, diagnosed with ‘Profound Mental Retardation’, Russia, June 2013

In many countries, children with disabilities continue to be discriminated against and “disproportionately” denied their right to education compared with children without disabilities.[81]

Human Rights Watch research indicates that many governments continue to have a strong focus on specialized, separate education for children with disabilities, with limited meaningful inclusion in mainstream schools. This has often led to significant tension on what type of education is best for children with very different types of disabilities.

Inclusive education focuses on promoting accessibility, identifying and removing barriers to learning, and changing practices and attitudes in mainstream schools to accommodate the diverse learning needs of individual students. Despite a global push to ensure schools are “universally designed”—or conform to inclusive standards of building which take into account mobility, access, and other requirements—classrooms, toilets, and school buildings remain inaccessible for children with disabilities.[82]

Rather than investing in more effective and cost-efficient changes to promote inclusive education in existing schools, Human Rights Watch has found that governments seeking to increase enrollment rates for children with disabilities focus on building costly special schools which cater to smaller numbers of children with disabilities, often grouping children by types of disabilities.[83] In Lebanon, for example, where there is limited inclusion of children with disabilities in education and many remain out of school, the government announced plans to build 60 new specialized schools for children with learning disabilities in 2016.[84]

Moreover, governments do not always implement “reasonable accommodation”—a key legal requirement under the CRPD to ensure schools accommodate children’s needs and do not discriminate against them—in ways that facilitate children’s accessibility or inclusion.[85] The burden is often on children and families to adapt to whatever service or type of education is available, or to drop out of school where schools do not provide additional services.[86]

|

In Nepal, children with disabilities represent a substantial group of the primary school-aged children who remain out of school. An estimated 85 percent of all out-of-school children in Nepal have disabilities.[87] The Nepalese government has adopted an inclusive education policy, but it has not done enough to ensure that children with disabilities attend school. The enrollment of children with disabilities in primary and secondary education continued to decline in 2014, despite government efforts which increased school scholarships for children with disabilities, developed a special curriculum for children with intellectual disabilities, and established a team tasked with developing a new national inclusive education policy.[88] |

According to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), “Inclusive education systems are designed to provide for a diverse constituency of students.”

In dealing with specific individual needs of students, “an inclusive system would respond by reviewing its practice to determine whether the gaps might be addressed systemically or through a reasonable accommodation measure. A reasonable accommodation fund should be set up to address the gaps.”[89]

Even when children with disabilities are in school, their education is often of poor quality. In China, Nepal, India, Russia, and South Africa, Human Rights Watch found that children with disabilities are affected by their teachers’ lack of knowledge, training, skills and motivation; and an absence of individualized planning and learning.[90] In many cases, pchildren with disabilities felt their teachers paid limited attention to their educational development, assuming they would not be able to learn or progress within school.[91] In many cases, mainstream schools do not receive additional budgets to accommodate children with disabilities, or to implement adequate measures to make schools more accessible.[92]

Institutionalization of Children with Disabilities

In Greece, India, Russia, Japan, and Serbia, among many other countries,[93] the harmful practice of institutionalizing children with disabilities continues, further isolating children from their communities, exposing them to violence and abuse in closed institutions, and depriving them of their right to education.[94] The lack of education programs in state institutions also severely impacts the ability of children and young adults with disabilities to study in schools and proceed to universities or technical or vocational colleges, and to feel included in their communities when leaving these institutions.[95]

|

In India, the involuntary admission and arbitrary detention of girls and women with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities in mental hospitals and residential care institutions significantly limits their right to education, despite national legislation which protects the right to education and makes it compulsory. Girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch were often denied their right to leave the institution to go to school, and those who did attend school often received an inferior education.[96] According to a representative of a local Child Welfare Committee, girls with disabilities in these institutions, “are not being taught anything. There is no dignity, no engagement. Nothing is being done for their self-esteem.”[97] |

Recommendations

|

Violence and Abuse in Schools

They would beat me when the teacher couldn’t see them, and my teacher didn’t know so wasn’t stopping it. My father visited the school director to complain, and the director said, ‘You should stop sending her to school if you’re worried about it.’ But my dad said I needed to study, so the director then told me not to interact with the other kids. I have no friends. It was difficult.… I didn’t enjoy anything about school this year. My teacher tried to scold the other kids, but they never stopped. They’d chant at me, ‘Syrian, Syrian,’ curse at me, and make fun of me for being older than them. In Syria, I loved school. I had friends. I loved learning. I miss my school in Syria very much.

—Fatima, 12, Turgutlu, Turkey, June 2015

School-based violence, including bullying, deeply affects children’s experience in schools. Violence within or near schools undermines children’s ability to learn, puts their physical and psychological wellbeing at risk, and often causes them to drop out of school entirely. According to the UN Girls’ Education Initiative, approximately 246 million girls and boys around the world experience school-related violence each year.[98]

The Convention on the Rights of the Child mandates governments to take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social, and educational means to protect children from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury, abuse, or negligence, among others.[99]

In 2014, UN member states committed, “to take all appropriate measures to prevent and protect children, including in school, from any form of violence, including forms of bullying, by promptly responding to such acts, and to provide appropriate support to children affected by and involved in bullying.”[100]

Sexual Violence and Abuse In and Around Schools

In many countries, sexual abuse and exploitation perpetrated by teachers and school staff, students, or adults providing school services is common.[101] Sexual abuse can happen in school toilets, classrooms, and staffrooms, on the way to and from school, and in teachers’ houses.[102]

Adolescent girls may also be exposed to sexual exploitation for grades, which may include mainly transactional encounters such as good reports or good marks in exchange for sexual acts, or sexual relations as payment for school fees or supplies.[103]

|

In Tanzania, Ana, a 16-year-old girl from Mwanza, who dropped out of secondary school as a result of the sexual harassment she experienced, told us:

|

In many countries, a pervasive culture of silence remains in schools, leading to insufficient accountability for perpetrators of sexual assault or violence against students. In South Africa, where Human Rights Watch found that sexual violence was a pervasive practice in many schools across the country, the very low rates of investigation and prosecution of perpetrators of sexual violence against school-going children have contributed to the widespread violation of girls’ rights in and around school.[105] In Tanzania, nongovernmental organizations focused on child protection told Human Rights Watch they struggle with justice at the school level, particularly when families of a child survivor of sexual violence often decide to settle for compensation from the family of the perpetrator to avoid stigma against the family.[106]

Girls’ negative experiences of sexual abuse and ongoing harassment in school will drive them out of school. Yet, too often teachers and school personnel who abuse children remain in schools. The lack of action to suspend, investigate, and remove teachers who abuse school children acts as a barrier for many girls, and indicates the lack of commitment to justice at the school level.[107] Moreover, the absence of child protection mechanisms accessible to children at the school level makes it difficult, if not impossible, for children and their families to seek redress.

Enforcing school safeguards, sensitizing male and female teachers, and creating space for child and adolescent-friendly reporting to relevant school authorities and the police should be strengthened in all countries where children experience ongoing violence and abuse in schools.

Compulsory Pregnancy and Virginity Testing

When we find a pregnant pupil in school, we call a school board meeting where we agree to expel the pupil.

—Head teacher, secondary school in Tanzania, August 2014

Under the guise of schools’ responsibility to monitor the upkeep of moral standards, many adolescent girls are routinely subjected to compulsory pregnancy tests in schools, and in some cases, may be subjected to humiliating, degrading, and unscientific virginity testing which has been condemned by international organizations, such as the World Health Organization.[108]

School officials are allowed to perform such tests on site, including groping students’ abdomens, or often identify girls who are ‘at risk’ of becoming pregnant and refer them to nearby hospitals for urine tests.[109] In schools, mandatory pregnancy testing can contribute to adolescent girls dropping out of school to avoid any humiliation or stigma.[110]

|

In Tanzania, schools routinely conduct mandatory pregnancy tests and expel pregnant girls. More than 8,000 girls are routinely expelled every year from school because they are pregnant.[111] Others stop attending school when they find out they are pregnant because they fear expulsion or stigma. Despite the evidence of negative and degrading impact of testing, a 2013 Ministry of Education toolkit recommends conducting periodic pregnancy tests as a way of curbing teenage pregnancies in schools,[112] but omits the need to ensure girls have access to comprehensive sexual education. Sharon, who married when she was 14, was expelled when she was in her final year of primary school: “When the head teacher found out that I was pregnant, he called me to his office and told me, ‘You have to leave our school immediately because you are pregnant.’” In 2015, the government adopted provisions to allow the admission of girls to school after they have given birth. However, the policy does not address the position of married girls explicitly and in 2016, Human Rights Watch found many girls continue to be barred from re-entering education or to deal with many barriers which push them out permanently.[113] The Tanzanian government does not appear to collect data on the numbers of girls who are expelled because they are pregnant or married. School officials told Human Rights Watch that they are only expected to record cases of “truancy.” |

Violence and Corporal Punishment

Are teachers good? No! They hit us, even with a hose.

—Abdullah, 11, in 5th grade, Amman, Jordan, October 2015

According to the Global Coalition to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, corporal punishment in schools has not been prohibited in 72 countries.[114]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child defines ‘corporal’ or ‘physical’ punishment as any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light.[115] Corporal punishment is degrading and humiliating, damaging the student's self-esteem, erodes students’ trust in their teachers, and makes students feel helpless and disengaged in school.[116]

|

In the United States, corporal punishment in public schools is routine in many parts of the country, and many school children, particularly children with disabilities, continue to be subjected to often violent and degrading punishment.[117] Children with disabilities are disproportionately more at risk of corporal punishment or violence in schools than other children. For hundreds of thousands of school children in the United States, violence inflicted by those in authority is a regular part of their experience at school. While 31 states and the District of Columbia have now banned corporal punishment, in 19 states it is legal for teachers or principals to punish public school students by hitting them repeatedly.[118] Corporal punishment usually takes the form of paddling (also called “swats,” “pops,” or “licks”). A teacher or administrator swings a hard wooden paddle that is typically a foot-and-a-half long against the child's buttocks anywhere between three and ten times. One student told Human Rights Watch that: "licks would be so loud and hard you could hear it through the walls.” A teacher reported that a principal turned on the loud speaker while paddling a student: “It was on the intercom in every class in the school…. He was trying to send a message … [l]ike, ‘you could be next.’”[119] |

The American Society for Adolescent Medicine has found that victims of corporal punishment often develop “deteriorating peer relationships, difficulty with concentration, lowered school achievement, antisocial behavior, intense dislike of authority, somatic complaints, a tendency for school avoidance and school drop-out, and other evidence of negative high-risk adolescent behavior.”[120]

Human Rights Watch has found that students exposed to corporal punishment or physical abuse are more likely to drop out.[121] However, girls and children with disabilities are often more vulnerable and at risk of being abused in schools. In Australia, for example, a school principal resorted to building a metal cage for a 10-year-old child with autism,[122] while in Nepal and South Africa, Human Rights Watch found that children with intellectual disabilities and autism who could often not communicate were often more vulnerable to harassment, mistreatment, and beatings by teachers and peers.[123]

Bullying and Harassment of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Children

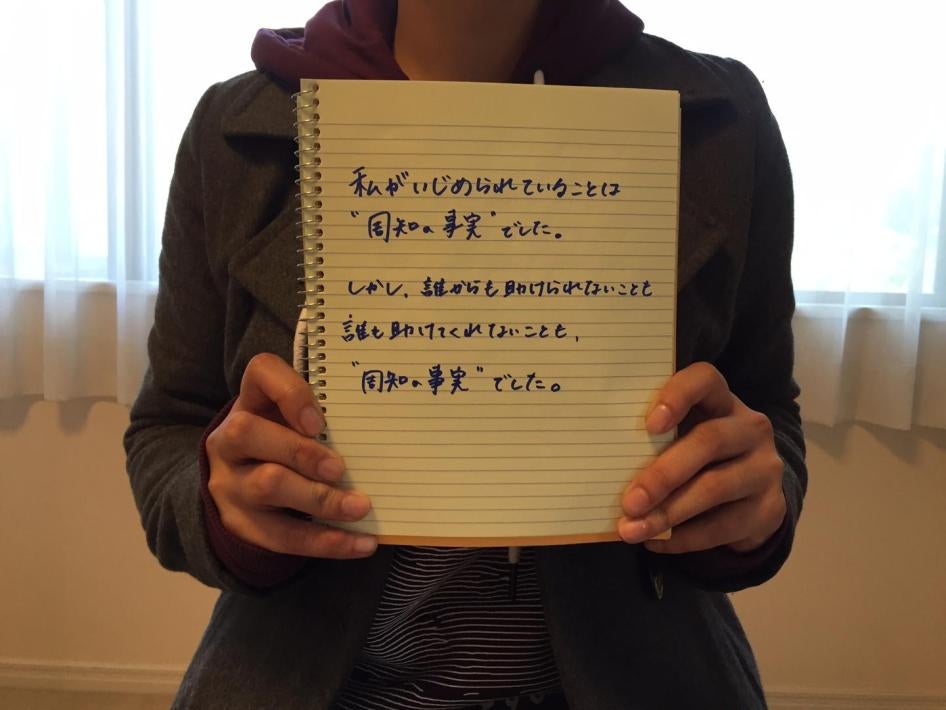

It was common knowledge that I was being bullied…it was also common knowledge that my teachers would never help me.

—A 20-year-old Japanese woman who was bullied by her classmates in junior high school, November 2015

Many lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) children and young people around the world are subjected to homophobic or transphobic bullying; gender-specific types of bullying that are based on actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity.[124] These violations are compounded by the failure of many governments to enact laws providing students with protection from discrimination and violence based on their sexual orientation and gender identity.[125] UNESCO recently documented numerous cases of homophobic and transphobic bullying in schools in the Asia-Pacific region, concludingthat schools are overwhelmingly unsafe for LGBT students.[126]

During investigations in Iran, Jamaica, and Japan, Human Rights Watch found that many of the LGBT youth interviewed had experienced bullying in school.[127] LGBT persons interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Iran indicated that primary school was one of the most traumatic periods in their life. Mani, a 29-year-old gay male from Tehran, said: “In primary school, we realize we are different from our peers, and because of this we become the focus of ridicule. The [kids] call us names like khaleh zanak (literally “auntie lady”) because we appear more feminine and because we don’t like to play like other boys. It is from this time that we begin to think that there is in fact something wrong with us.”[128]

|

In Japan, LGBT youth reported being the victims of homophobic and transphobic bullying, violence, and discrimination by both peers and teachers.[129] Even in the absence of the criminalization of same-sex behaviour, bullying and discrimination affects the right to education and creates an unsafe learning environment for LGBT students and those who do not conform to gender norms and societal expectations.[130] Transgender students face legal barriers to accessing education because the country’s legal recognition procedure for transgender people is inaccessible for those under 20, and contains abusive and discriminatory requirements—including coerced sterilization—for those who want to be legally recognized in their gender identity. Japanese transgender students told Human Rights Watch they faced harassment and bullying when their schools forced them to access lavatories according to the gender they were assigned at birth, for example, leading to school drop-outs. Japan’s schools feature deeply-engrained gender separation and stereotypes. Nearly all junior high and high school students are required to wear gender-specific uniforms, and school activities are often gender-segregated. For children exploring their gender identity or those who identify as transgender, such an environment can be harsh. “The Japanese school system is really strict with the gender system,” a transgender high school teacher told Human Rights Watch. “It imprints on students where they belong and don’t belong—in later years when gender is firmly tracked, transgender kids really start suffering. They either have to conceal and lie or act like themselves and invite bullying and exclusion.”[131] |

***

|

In the United States, around two thirds of LGBT students are bullied in school and it is estimated that one third of LGBT children skip or drop out of school as a consequence of their negative, unsafe, and discriminatory experiences in school.[132] Ursula (pseudonym), 16, a transgender student in higher secondary school, in Alabama, told Human Rights Watch: They refused to put me in girls’ physical education last year, and I was scared to go in the locker room and dress out and wouldn’t participate, and so I failed. I requested to do girls physical education and it’s been over a month—I don’t think they’re making the decision. And I need a whole year of physical education to graduate. I’m worried about physical bullying and verbal bullying in the locker room, and harassment—I’ve experienced harassment every time I went in there, and finally I just couldn’t do it anymore.[133] |

Lack of Comprehensive Sexuality Education in Schools

I didn’t know that I would get pregnant by having sex… I was just playing sex.

—Gloria C., who got pregnant at age 14 or 15, Yambio County, South Sudan, March 2012

In many countries, schools often do not offer comprehensive sexuality education or only offer a limited sex education curriculum when it is already too late for many students. Health workers and teachers do not share complete information about reproductive health with adolescents, and very often information is not available in accessible formats for people with disabilities.

When it is available, sexual and reproductive health education is often not a stand-alone topic, distinct from biology curricula. Paradoxically, in some countries, students only access sexual and reproductive health modules towards the end of lower secondary education, when a significant proportion of girls have already dropped out or become pregnant. Children who are behind in school because of delays related to poverty, disability, or other factors are also less likely to be in the right class at the right time to benefit from sexual and reproductive health modules taught in school.

Children and young adults interviewed by Human Rights Watch referred to the limited, and often incorrect and unscientific, information they receive at school about pregnancy, sexuality, and HIV/AIDs prevention.[134] In many cases, children and young adults interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had limited or no inclusive access to comprehensive sexual education or contraception had become pregnant without understanding how or had become infected with HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases.[135]

The UN Population Fund (UNFPA) states that: “Comprehensive Sexuality Education empowers young people to take control of their own behavior and, in turn, treat others with respect, acceptance, tolerance, and empathy, regardless of their gender, ethnicity, race, or sexual orientation.”[136] UNFPA’s Operational Guidance for Comprehensive Sexuality Education also highlights how students can “explore and nurture positive values and attitudes towards their sexual and reproductive health, and develop self-esteem, respect for human rights, and gender equality.”[137]

According to the UN special rapporteur on the right to education, “In order to be comprehensive, sexual education must pay special attention to diversity, since everyone has the right to deal with his or her own sexuality without being discriminated against on grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity.”[138]

The UNESCO International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education puts the impetus on policymakers and education officials at schools to take a leadership role in promoting sexuality education.[139]

Recommendations

|

Persistent Exclusion of and Violations Against Girls

Short-changing girls is not only a matter of gender discrimination; it is bad economics and bad social policy…Indeed, world leaders at United Nations conferences throughout the 1990s, have acknowledged that poverty cannot be overcome without specific, immediate and sustained attention to girls’ education.

—Kofi Annan, former United Nations Secretary-General, ‘We the Peoples,’ 2000

Traditional biases against girls, the exclusion of girls from school activities, sexual harassment, child marriage, early pregnancy, and violence in and around school, particularly sexual violence, are some of the factors and violations which disproportionately affect girls, including girls with disabilities.[140] At the school level, the lack of concrete gender-specific policies and approaches to transportation, the lack of separate toilets or sanitation facilities, or the lack of adequate child and gender protection safeguards in schools contribute to higher drop-out rates among girls.[141]

All 189 governments that are state parties to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) must “take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in order to ensure them equal rights with men in the field of education.” Additionally, governments must guarantee girls have the same conditions to access studies at all educational levels, to access the same quality of education, as well as further opportunities to access higher levels of education.[142]

Child Marriage and Early Pregnancy

Child marriage ruined my life. Now I do not work and cannot find a job because I stopped going to school.

—Confidence S., 22, married at age 14 to a 42-year-old man, Zimbabwe, November 2015

Many girls leave schools prematurely and end their education when they are forced into early marriages.[143] International and regional obligations explicitly state that the minimum age of marriage should be 18, and marriages should be entered into with the free and full consent of both spouses.[144]

Human Rights Watch has documented the impact of child marriage on the right to education of many girls in countries as diverse as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Malawi, Nepal, South Sudan, Tanzania, Yemen, and Zimbabwe.[145] Many girls told Human Rights Watch that they found it difficult to return to school after marriage because of discriminatory school policies, lack of money for school fees, lack of child care, unavailability of flexible school programs or adult classes, lack of early childhood services for their children, and the need to do household chores. Others said that their husbands, own family members, or in-laws would not allow them to continue school after marriage.

In South Sudan, Akur L., who married at the age of 13 in 2003 and dropped out of school, said:

My uncles forced me to marry a man who was old enough to be my grandfather. I was going to school and in class six. I liked school. If I was given a chance to finish school, I would not be having these problems, working as a waitress and having separated from my husband.[146]

Adolescent pregnancy outside of marriage, or the fear that adolescent girls will get pregnant or will be exposed to sexual harassment, also helps fuel child marriage.[147] According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNPFA), “Many countries have taken up the cause of preventing adolescent pregnancies, often through actions aimed at changing girls’ behavior. Implicit in such interventions are a belief that the girl is responsible for preventing pregnancy and an assumption that if she does become pregnant, she is at fault.”[148] Many governments enforce policies which automatically exclude pregnant girls from schools and terminate their education.[149]

|

In Zimbabwe, if a girl becomes pregnant, spends the night outside the family home, is seen with a boyfriend, or returns home late after seeing a boyfriend, her family may force her to marry for the sake of honor. In some cases girls who become pregnant or are sexually active decide to enter a customary marriage because they fear being rejected, beaten, or abused by relatives. According to UNICEF, nearly one-third of girls in Zimbabwe marry before their 18th birthday and 4 percent marry before they turn 15.[150] Nearly all the child brides Human Rights Watch interviewed were not able to continue their education after marriage, either because of their financial situation, their husband would not permit it, or they had to care for a baby. Many indigenous apostolic churches forbid girls to continue education after marriage. Abigail C., 15, told Human Rights Watch: I fell pregnant last year when I was 14 years old. I had stopped going to school that same year because my mother, who works as a maid earning $50 per month, could not afford to send me to school. I had an affair with an older man who had a wife. The woman who lives next door is the one who persuaded me to have an affair with this man. I received no sex education at all, and, when I had sex with this man, I fell pregnant. I went to live with his mother because he was staying with his first wife. In June, I went to hospital and gave birth to a baby, who died within a few minutes of birth. The nurses told me my baby died. After that I went back to live with my mother. I wish to go back to school because I am still a child.[151] In July 2015, Zimbabwe became the eighth country to join the African Union campaign to end child marriage in Africa. The government has yet to finalize and implement a national action plan on ending child marriage, as the African Union has requested.[152] |

In the minority of cases where young mothers of school-going age are allowed to go back to school by school officials, they may face high levels of stigma and negative attitudes in school.[153] In South Sudan and Tanzania, Human Rights Watch found that girls who had become mothers often had to change schools to prevent being stigmatized by their former peers or teachers. Many dealt with new barriers associated with enrolling in alternative schools which were often further away from their homes. Many girls have to balance the need to combine studying and working to pay for their children’s expenses.[154]

The new UN Sustainable Development Goals, adopted in September 2015, include a goal to eliminate child marriage as a key target by 2030 for advancing gender equality. Meeting this target requires a combination of approaches, including: a commitment of political will and resources over many years; willingness to acknowledge adolescent girls’ sexuality and empower them with information and choices; and true coordination across various sectors, including education, health, justice, and economic development.[155]

Menstrual Hygiene and Lack of Adequate Sanitation in Schools

When [the girl’s] menstrual cycle began, she had blood on the bench. Her friends teased her and the teacher beat her. From the next day, she didn’t come again.—Director of an NGO working with marginalized girls, Nepal, 2011

|

In Bangladesh, a lack of hygienic materials and private toilets are a factor in girls’ absence from school. This becomes more difficult for girls to manage as they reach the onset of menstruation, when they become particularly likely to miss school during menstrual periods. A study found that 40 percent of girls reported missing school during menstruation for an average of three school days each menstrual cycle.[156] In this study, 82 percent of girls said their school facilities were not appropriate for managing menstrual hygiene, 12 percent had access to female-only toilets with water and soap available and only three percent said the toilet they used had a trash bin.[157] Gaps in attendance caused by a lack of sanitation and care for menstrual hygiene also compromise girls’ eligibility for government stipends linked to attendance, cause girls to fall behind in their studies, and undermine parental support for keeping girls in school.[158] |

Girls’ right to education can be severely curtailed when schools lack separate, safe, and clean sanitation facilities, or clean water to manage menstruation. Sanitation-related barriers can lead to low attendance and contribute to high dropout rates for girls.

In Nepal, Sunita, age 19, told Human Rights Watch, “The government should build toilets in schools. We had a toilet, but it was not good. If there are proper toilets, girls will feel better when they are on their periods and have to change their pads. Many girls stay home during their periods. They were marked absent and wouldn’t be able to learn. They couldn’t catch up because the course would have moved on. They would try to sit with their friends and catch up, but the teacher wouldn’t repeat [information]. Some of them left school because of this. Some got married then, some did not.”[159]

Girls who cannot afford sanitary napkins or who cannot change or dispose of them privately may miss school during their periods.[160]For example, UNICEF estimates that 1 in 10 African girls miss school during menstruation, which contributes to higher school drop-out rates for some girls.[161] Human Rights Watch spoke with girls in Haiti who leave school to go home to wash and change the materials they use to manage their menstruation because they cannot do that at school. This caused some to miss as much as 30 minutes of instruction every time they needed to change their materials.[162] Teachers in Haiti also told Human Rights Watch that girls sometimes stay at home during menstruation because they have no option to manage their hygiene at school.[163]

Even if girls do go to school during their periods, they may feel less empowered or focused to participate if they lack sanitary supplies. Female teachers are also affected but may not provide support due to engrained taboos about periods.[164] In Tanzania, adolescent girls told Human Rights Watch they find it challenging to go to school and generally have very little information and no one to talk to about periods, including female teachers.[165]

Michaela, who attends Form 4 said: “If you sit for too long, you find that blood appears on your skirt. Boys laugh at you.”[166]

Moreover, girls with disabilities face additional challenges. In Nepal, girls with disabilities often drop out of school once they reach puberty because there are no support services in school. Not being able to move, dress, and use the bathroom independently increases their vulnerability to intrusive personal care or abuse. Accessible and inclusive menstrual hygiene management and sanitation facilities are therefore particularly important in enabling girls with disabilities to continue their education.[167]

Prioritizing the construction or maintenance of adequate, accessible, and separate, locking sanitation facilities, with access to safe drinking water and waste disposal facilities, increasing the availability of hygiene materials in schools (including in different formats such as plain language and Braille), and ensuring schools talk about menstruation to girls and boys, should be a policy priority for more governments. [168]

Recommendations

|

Education under Attack

In 2015, conflict disrupted the education of millions of children, and according to Leila Zerrougui, the UN secretary general’s special representative of the secretary general for children and armed conflict, armed “groups perpetrating extreme violence also particularly targeted children pursuing their right to education.”[169]

Attacks on Schools

[The army] fired on my school with a tank. It was during science class, but I was on my way to the bathroom. Two shells hit the fourth floor. I was on the first floor. People started running away. When I ran away, ashabiha [a state sponsored militia] caught my shoulder, but I struggled and managed to get away. Theshabiha came into the school and shot the windows, broke the computers. After that, I only went back to take my exams.

—Rami, 12, a refugee from Daraa governorate in Syria, interviewed in Ramtha, Jordan, November 2012

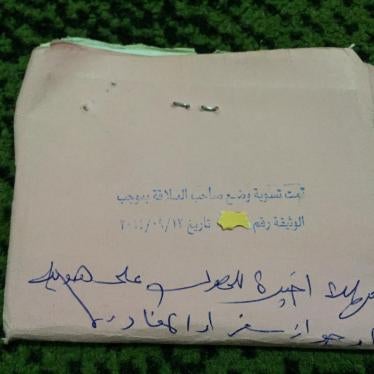

|

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Human Rights Watch documented attacks on schools, students, and teachers. Children were also forcibly recruited by armed groups in schools or while walking to or from school. Many were then sent to fight on the battlefield with little to no training or served as porters or cooks, and many of the girls were forced to be sex slaves.[170] A local resident told Human Rights Watch: “The first time the M23 [rebels] came to attack, the FARDC [Congolese Armed Forces] had occupied our school…. And when the FARDC had been driven out by the M23, then the M23 also occupied our school…. Our school became the battlefield.”[171] |

Attacks against schools have resulted in the damage and destruction of school buildings, the death of students and teachers in or near school compounds, and the closure of schools.[172]> According to the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, since mid-2009, more than 30 countries have experienced a pattern of targeted attacks on schools, teachers, and students, or the military use and occupation of schools by armed forces and armed groups.[173]

Under international humanitarian law, schools and other educational structures are civilian objects that are protected from attack. They may only be attacked if, and only for such time as, they are military objectives—those objects that contribute to the military action and whose destruction at that time would offer a definite military gain. Moreover, attacks on valid military targets—including school buildings being used for military purposes—must be neither indiscriminate nor disproportionate. Intentional attacks on buildings dedicated to education are war crimes, as long as the building is not a military objective.[174]

|

In Ukraine, since 2014, armed groups have shelled schools, destroyed resources, and forced schools to close during the conflict. Even when schools re-opened in an attempt to continue, merging students led to overcrowding, some schools operated on a double-shift system, and the number of teaching hours for children has been reduced.[175] In one school which had a pre-conflict enrollment of 370 students, classes were interrupted several times throughout the conflict, because of the intensity of hostilities. The school’s principal said: “In September, October, and November 2014 there were no classes, school was closed. By mid-December, the school re-opened and remained open until winter holidays [New Year’s break]. Then there were a few days between January 15 and 19 [when the school was open] and then—active fighting. We had to shut down again. There was no electricity or heating for two months. We had to survive—we survived the best we could.”[176] |

Military use of schools

In the past decade, armed forces and non-state armed groups, and at times international peacekeeping forces have used schools and other institutions for military purposes, in at least 26 countries with armed conflict in Africa, the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.[177]

In some cases, armed forces and armed groups have turned schoolgrounds into battlegrounds, taking over educational institutions–kindergartens, daycare centers, schools, and universities—for military purposes.[178] Schools have been used as barracks, logistic bases, headquarters, weapons and ammunition storage caches, detention and interrogation centers, and recruitment grounds in the majority of conflicts in recent years.[179]

Students and teachers have been displaced entirely or, in other instances, forced to try to study with armed men present in their school, potentially endangering their lives and safety, as well as their right to education. Even where schools are vacant at the time, the damage to school infrastructure from looting and attacks by opposing forces, as well as, in some instances, the ongoing presence of troops when schools could reopen may prevent children from resuming their education. [180]

In investigations in Afghanistan, India, Yemen, Pakistan, South Sudan, Syria, and Nigeria, among others, Human Rights Watch found that in addition to endangering students’ and teachers’ safety, military use of schools also hinders children’s access to education and lowers the quality of learning. It can disrupt studies, lower school enrollment, decrease school attendance, and cause damage school infrastructure.[181]

|