Summary

“We are Dominican”

—Adaptation of a popular slogan used in rallies by Dominicans of Haitian descent, “I am Dominican and I have rights”

Rosanna is a bright 17-year-old who was born in the Dominican Republic. She was raised by parents who migrated from Haiti over 20 years earlier. For two years she has been unwittingly enmeshed in an increasingly contested national struggle over who is, and who is not, a Dominican national.

In 2013, a Dominican high court ruling retroactively removed citizenship from tens of thousands of Dominicans. Most of them, like Rosanna, are of Haitian descent—a historically marginalized community. This has left them unable to perform basic civil functions such as register children at birth, enroll in school and university, participate in the formal economy, or travel in the country without risk of expulsion. Forced to quit public school, Rosanna now picks and sells fruit in the countryside for less than $3 a bucket.

In 2014, President Danilo Medina’s administration attempted to mitigate the high court ruling with a naturalization law aimed at recognizing the citizenship claims of those affected by the 2013 decision.

The 2014 Naturalization Law offered a seemingly simple solution: the government would recognize the nationality of those already registered with the state as Dominicans, and issue any additional documents necessary to fully exercise their citizenship rights. For those not yet registered, the government would first establish a registration process, then issue the requisite documents for those entitled to citizenship.

However, despite a promising legal framework, Human Rights Watch research finds that the law has been fraught with design and implementation flaws that have thwarted the re-nationalization process. This report outlines the context for denationalization, details the laudable intent but practical failures of the 2014 Naturalization Law, and documents arbitrary expulsions and questionable legal procedures that various government entities have carried out in contravention of the law’s stated goals. These practices continue to arbitrarily deprive individuals of their right to Dominican nationality and citizenship-related rights. Despite the law’s shortcomings, in August 2015, the government is due to begin expelling those, like Rosanna, who were denationalized.

Ongoing Human Rights Violations

Human Rights Watch research documented a number of problematic trends that illustrate the country’s ongoing violations of the human right to a nationality.

In the case of registered nationals, Human Rights Watch found that government agencies responsible for civil registries have refused to restore original nationality documents. Instead, officials have begun segregating those denationalized in 2013 into completely new civil registries. This so-called “transcription” process is not only unnecessary and resource-intensive, but it has also impeded many from enjoying full citizenship rights. Many registered nationals are still unable to register children at birth, enroll in school, and participate in the formal economy. Moreover, military and immigration authorities have repeatedly profiled registered nationals of Haitian descent, detaining and forcibly expelling them, even when they do possess valid documentation.

In the case of unregistered nationals, Human Rights Watch documented a registration process that forced Dominicans, mostly children, to register as “foreigners” before being naturalized. The process has not only violated human rights law, it has been impossible for many to access on its own terms. Government officials have imposed onerous documentation requirements that have summarily excluded many from registration, especially given the brief 180-day implementation window.

Based on Human Rights Watch’s assessment, it appears this has disproportionately impacted children whose mothers lack identity papers and cannot obtain documentation within the time period needed. Additionally, military and immigration authorities have harassed, detained, and expelled individuals seeking to enter the civil registries through the registration process as well.

Though Rosanna wanted to register under the Naturalization Law, she was unable to do so. Faced with an inscrutable bureaucratic process, and unable to afford a lawyer, she depended on the help of thinly stretched civil society organizations to guide her through the process. Unfortunately, Rosanna’s case was only identified in the final month of the registration process, and her file could not be completed in time. She is now permanently barred from entering the Dominican civil registries.

***

Government officials have argued that, in cases like those of Rosanna, administrative processes are necessary to avoid nationality fraud, and ensure the rule of law. Fair and transparent regulation of the citizenship process is of course valid.

In practice, however, officials have developed burdensome, resource-intensive processes that put unnecessary and unjustified bureaucratic obstacles in the way of those eligible, leading to harassment and violations of fundamental rights.

The Dominican government’s decision to adopt a Naturalization Law was an important first step in trying to solve the country’s ongoing denationalization crisis. But much work remains to be done.

As the August deportation deadline looms, Human Rights Watch calls on Dominican authorities to halt expulsions of denationalized Dominicans, to promptly restore their citizenship, and to respect their right to a nationality. It also urges the government to work with civil society, the Haitian government, and other international stakeholders to guarantee that individuals are not arbitrarily and permanently deprived of their Dominican nationality.

Unless Dominicans authorities act now, Rosanna will not be going back to school this fall. Instead, she faces the prospect of being forcibly sent from the country where she was born and raised, on a one-way bus to Haiti.

Glossary

The following key terms concern the denationalization of Dominicans, and the implementation of the Naturalization Law. As noted, several of these terms have specific legal meaning in this context.

|

Category A nationals |

A subset of registered Dominican citizens, defined by Law 169-14. Category A nationals have been registered as Dominicans, but have alleged irregularities in their civil registry on account of being descendants of undocumented migrants. Category A nationals are currently being audited and transcribed due these irregularities. Many are still unable to exercise their citizenship rights. |

|

Category B nationals |

A subset of unregistered Dominican citizens, defined by Law 169-14. Category B nationals are people born in the Dominican Republic before April 18, 2007, and who did not register as Dominicans. Like Category A nationals, Category B nationals are descendants of undocumented migrants. |

|

Dominicans of Haitian descent |

People of Haitian ancestry who either already have Dominican nationality, or who are eligible for Dominican nationality.[1] |

|

Expulsion |

The process by which state actors forcibly remove a national from their country of nationality. In contrast to the deportation of migrants, this report uses the term expulsion to refer to the removal of Dominican nationals. |

|

Registered nationals |

Any Dominican citizen properly registered as such in Dominican civil registries. A subset of registered nationals correspond to the so-called Category A of Law 169-14. |

|

Registration |

The process by which government officials enter a person into Dominican civil registries. People may be entered into one of three registries: the regular civil registry for nationals, the civil registry for non-nationals, and the (new) civil registry for transcribed nationals. The Naturalization Law established a special registration process to enter nationals into the registry for non-nationals, and then re-nationalize these individuals in a two-year period. |

|

Regularization |

The process established by presidential Decree No. 327-13 to provide authorization for undocumented migrants to remain in the country. The National Plan for the Regularization of Foreigners began accepting applications in June 2014, and the application period ended May 2015.[2] |

|

Re-nationalization |

The process established by Law 169-14 to reinstate the nationality of Dominicans affected by a 2013 ruling of the Dominican Constitutional Tribunal. As described in Section I, the process is slightly different for Category A and Category B nationals. |

|

Transcription |

The process by which government officials copy the information in original civil registries into special “transcription” registries, and then annul original registries.[3] |

|

Undocumented migrant |

A person who immigrated to the Dominican Republic—or currently lives in the country—without government authorization. |

|

Unregistered national |

Individuals with a claim to Dominican nationality, who are not presently in the civil registries. |

This report uses both the terms “nationality” and “citizenship” interchangeably. This is also common in international human rights texts and documents, including judgments from international human rights bodies. In certain contexts and legal frameworks, nationality and citizenship have two technically distinct meanings; however, such situations do not arise in the scope of (and are not relevant to) this report.[4]

Recommendations

To the Dominican Government

To the Administration of President Danilo Medina

- Ensure that the General Directorate of Immigration and the Armed Forces do not pursue measures that would forcibly expel denationalized Dominicans to Haiti.

- Work with Congress to develop a registration process that guarantees effective access to the civil registries for children born in the country before the constitutional reform of 2010.

To the Central Electoral Board

- Stop the transcription and nullification of birth records of registered nationals, and instead immediately reaffirm the legal status and validity of their pre-existing nationality documents.

- Implement registration protocols that ensure Dominican parents can properly recognize their children and register them as Dominican nationals at birth, with particular attention to overcoming barriers currently faced by Dominican fathers trying to register their children.

To the General Directorate of Immigration and the Armed Forces

- Implement a deportation protocol consistent with international standards, and prior accords with Haiti, that individually accounts for each person deported, protects denationalized Dominicans from expulsion, and preserves family unity.

- Ensure that, if erroneously removed, denationalized Dominicans be allowed to return promptly to their homes in the Dominican Republic.

- Vigorously enforce laws sanctioning immigration and army officers who extort or otherwise abuse migrants and denationalized Dominicans during the deportation and expulsion process.

To the Haitian Government

- Ensure the prompt documentation of Haitian migrants living in the Dominican Republic, including providing greater access to consular facilities.

- Work with the Dominican government to establish a protocol to identify denationalized Dominicans who have been deported, and advocate before the Dominican Republic for their prompt return.

To the Governments of the United States, the European Union, and Canada, and to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- Support civil society groups to help monitor the deportation process, and protect the rights of denationalized Dominicans.

- Work with the Dominican government to develop a process that will enable denationalized Dominicans to effectively regain their nationality.

To States of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM)

- Publicly reiterate the need for the Dominican Republic to conform to international human rights standards. Make the Dominican Republic’s entry into the CARICOM community contingent on a solution to the denationalization crisis.

Methodology

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch conducted over 100 interviews with a range of actors. These included abuse victims, their relatives, community leaders, representatives of local human rights organizations, legal experts, government officials, and representatives of international organizations.

A Human Rights Watch researcher traveled to the Dominican Republic for eight weeks between February and May 2015. Interviews were conducted in a number of provinces around the country, including La Romana, El Seibo, San Pedro de Macorís, the Distrito Nacional, Provincia de Santo Domingo, Monte Plata, Sánchez Ramírez, Santiago, Valverde, Dajabón, Bahoruco, Independencia, and Barahona. Most interviews were conducted in person, although some were also conducted over the phone. No interviewee received financial or other compensation for talking to us. Nearly all interviews were carried out in Spanish by the researcher. A few interviews were conducted in Haitian Creole and Spanish, with the help of a translator.

Cases that Human Rights Watch documented were verified through a combination of interviews with victims, interviews with victims’ lawyers, legal files, and other documentary evidence. The specific evidence gathered for each case or set of cases is explained within the report.

Human Rights Watch research also drew on other sources, including official statistics, court rulings, official reports, publications by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and news articles.

In some cases, full names and other identifying information have been withheld from publication at the request of interviewees who cited fear of reprisals. Some details about individuals and locations have been also withheld when requested, and when Human Rights Watch believed the information could place someone at risk. All such details are on file with the organization.

I. Background: Denationalization and Its Aftermath

In 2013, the Dominican Constitutional Tribunal summarily denationalized—or removed citizenship from—tens of thousands of Dominicans. This decision, based on a retroactive reinterpretation of Dominican nationality law, violated international human rights law, curtailed fundamental rights, and made people vulnerable to expulsion.

In 2014, the administration of President Danilo Medina responded by helping to negotiate and pass a law to re-nationalize many of those affected by the decision. Commonly known as the Naturalization Law, it demonstrated that the government was initially committed to addressing the denationalization problem, and upholding the country’s human rights obligations.

However, the law has been riddled with design and implementation flaws that have thwarted the re-nationalization process, and which continue to prevent individuals from exercising their right to a nationality. According to official estimates, tens of thousands have been unable to re-nationalize, and the government has said it will begin deporting nationals without proper documentation in August 2015.[5]

Dominicans of Haitian descent have been particularly affected by these legal and policy developments. A historically marginalized community, they are the single largest ethnic group affected by the 2013 decision and the 2014 law.

Mass Denationalization and Statelessness

According to the Dominican Constitution, everyone born in the country between 1929 and 2010 was a Dominican national or citizen, with the exception of those whose parents were “in transit.”[6] Until recently, however, Dominican nationality law did not clearly define who was “in transit,”[7] or whether the term applied to undocumented migrants resident in the country.[8]

In practice, the government applied nationality law inconsistently. Many undocumented migrants successfully registered children born in the Dominican Republic as Dominican nationals.[9] In many other instances, parents either failed to register their children, or were prevented from doing so by government officials.[10]

In September 2013, the Dominican Constitutional Tribunal defined “in transit” to include undocumented migrants in its ruling TC 168-13.[11] The tribunal retroactively applied this definition to the constitution of 1929.[12] The decision thus affected anyone whose claim to citizenship was based on being born in the country, but whose parents (or grandparents) were undocumented migrants who had entered the country after 1929.

The impact of the ruling was severe.

Civil society groups estimated that hundreds of thousands of Dominicans were denationalized by the decision.[13] Affected individuals were left in a precarious state, unable to reclaim their most basic rights, and denied nationality documents necessary for basic transactions, including registering children at birth, enrolling in school and university, participating in the formal economy, and traveling within the country without risk of deportation.[14]

The move was widely criticized domestically and internationally. Dominican legal experts condemned the decision for its inaccurate reading of the country’s constitution and nationality law, and its retroactive application.[15]

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights called the decision a discriminatory and “arbitrary deprivation of nationality” at odds with the country’s international obligations.[16] The Inter-American Court supported this conclusion.[17] Furthermore, the commission, the court, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) all expressed serious concern about the statelessness created by the decision.[18]

Attempt to Re-Nationalize

The administration of President Danilo Medina mobilized to mitigate the impact of the denationalization crisis.[19] In early 2014, the President’s office worked with Congress to draft a bill that would re-nationalize those affect by ruling TC 168-13.[20] In May 2014, Congress unanimously passed Law 169-14, the Naturalization Law, as an urgent legislative measure.[21]

The Naturalization Law divided those affected by the decision into two groups. In “Category A” were individuals already registered as Dominican nationals.[22] These individuals were already in the civil registries, and often had nationality documents, such as birth certificates, identification cards, or passports.

In “Category B” were nationals who were born in the country and thus entitled to Dominican nationality, but had not been registered yet.[23] These individuals were not in the civil registries, and had no official documentation from the Dominican government.

The plan for registered nationals was straightforward. Since these people were already in the civil registries, the government’s Central Electoral Board (CEB) simply had to recognize existing registries as valid, and, if necessary, issue nationality documents.[24]

The plan for unregistered nationals was more complex. Because these individuals were not registered, the law devised an administrative process to register them. The implementation of the process was delegated to the Ministry of Interior and Police.[25]

Nationals protected by Law 169-14:

|

Registered nationals (Category A) |

Unregistered nationals (Category B) |

|

Definition: Individuals already registered as Dominican nationals. Many already have birth certificates, identification cards, and other nationality documents. |

Definition: Individuals born before April 18, 2007, but not registered as Dominican nationals. These individuals have no nationality papers. |

|

Re-Nationalization Process:

|

Re-Nationalization Process:

|

|

Progress: In practice, the CEB has first transcribed original registries into new transcription registries, issued new documents, and tried to nullify original registries. Many still are unable to use their papers to register children or go to school or university. |

Progress: The registration process ended in February 2015. The MIP has not yet given final responses as to who is registered. |

To register, individuals first had to prove they had been born in the country, and then they would be registered as non-nationals. After two years, they would be given an opportunity to be naturalized by presidential decree.[26] Unregistered nationals were given 90 days to apply for registration, beginning in late July 2014.[27]

After only around 1,500 people were able to apply for registration in the short initial registration period, applicants were given a single 90-day extension, which ended on February 2015. [28] According to the Ministry of Interior, 8,755 individuals applied for registration.[29] The government has not yet provided a final number of approved applications.

To allow people to benefit from the law, and give them time to register, the government announced it would halt deportations of those denationalized until June 15, 2015.[30] This date was later changed to early August 2015.[31]

Ongoing Arbitrary Deprivation of Nationality

While the Naturalization Law has been a significant step towards remedying the denationalization problem, the law does not fully conform to human rights law.

The right to a nationality, and to not be arbitrarily deprived of nationality or denied the right to change nationality, is contained in Article 15 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, and guaranteed in Article 20 of the American Convention on Human Rights.[32]

The convention in particular gives a person the right to be a national of the state in which they are born, provided they do not have the right to another nationality.[33]

In the 2014 Case of Expelled Dominicans and Haitians vs. Dominican Republic, the Inter-American Court explicitly held that ruling TC 168-13 of the Constitutional Tribunal violated Article 20 of the convention.[34] The court held that the Constitutional Tribunal’s ruling constituted an arbitrary deprivation of nationality,[35] and that the Dominican Republic had a responsibility to restore the nationality of those affected by the ruling.[36]

The court also held that the Naturalization Law did not fully restore the right to a nationality of those affected by TC 168-13.[37] As a legal matter, the court noted that the Category B registration process effectively considered unregistered nationals non-nationals by making them register as foreigners who may then be nationalized after a period of two years.[38] As a practical matter, it also considered the whole administrative process an “obstacle in the enjoyment of their right to a nationality.”[39]

The court did not evaluate Category A of the law, due to insufficient evidence presented before it.[40]

Human Rights Watch research supports the court’s conclusion that, as both a legal and a practical matter, the Naturalization Law continues to violate the right to a nationality for unregistered nationals in Category B.[41] Similarly, as this report documents, in theory and in practice, the re-nationalization process for Category A also continues to violate the right to a nationality of registered nationals.[42] As described in Section II, the government continues to limit people’s enjoyment of the right to a nationality by unnecessary bureaucratic processes, as well as arbitrary detentions and deportations.

Impact on Dominicans of Haitian Descent

Haitians have long comprised most of the migrant population to the Dominican Republic. For over a century, Haitian migrants have migrated to the Dominican Republic to contribute to its economy. They have integrated themselves into Dominican communities and built families in the country. Today, Dominicans of Haitian descent are the country’s largest ethnic group with migrant roots.[43]

Troubled History

Haitian migrants and their descendants have had a historically complex and often charged relationship with Dominicans. Migrants have been an important source of cheap labor for the Dominican sugar industry since the early twentieth century.[44]Even with the decline of sugar production in the 1980s, migrants continue to play a crucial role in the Dominican economy, notably in agriculture, construction, and tourism.[45]

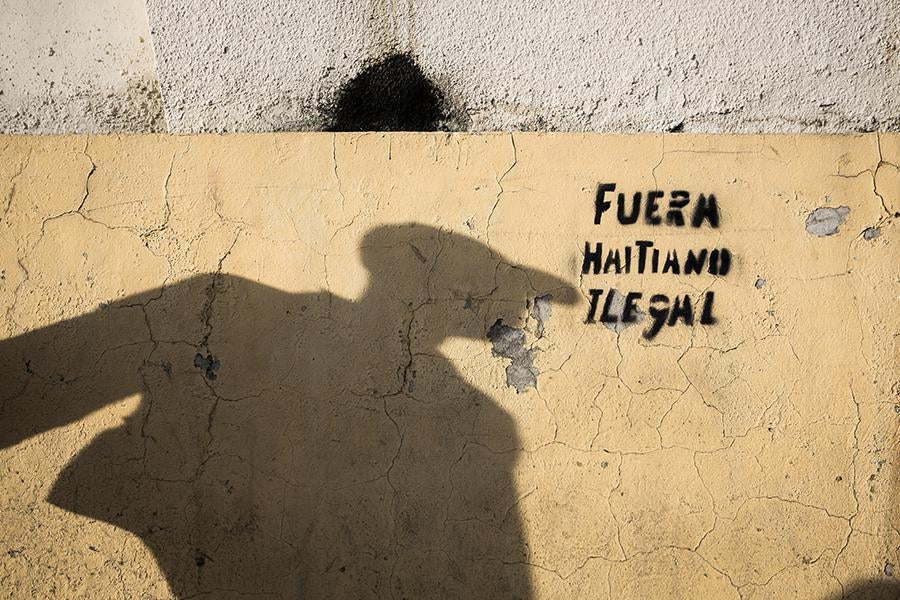

For nearly a century, however, nationalist sectors of the Dominican social and political elite have also used Haitian migrants and their descendants as a convenient political scapegoat. Encouraging fears of Haitian influx has historically been a strategy for politicians to gain popular support and consolidate power.[46] While many Dominicans have peacefully coexisted alongside Haitian migrants and their descendants, nationalist fears have also resulted in acts of state-sanctioned and popular violence towards Haitians.[47]

In the current debates, political figures have revived common fears of a “pacific Haitian invasion” that will become a social burden for Dominicans.[48] Theories of a conspiracy to join the two countries have also regained popularity.[49]

In this climate, human rights advocates and civilians have been targeted with threats and violence. In February 2015, a Haitian man was lynched in a public park, although the motive for the killing has not been established.[50] Human Rights Watch spoke with two Dominicans of Haitian descent in March who said they had been assaulted by half a dozen people at a bus station on account of their “being Haitian.”[51] In April, a mob beat members of a Haitian community in the province of Espaillat, after two Haitian migrants were allegedly accused of killing a Dominican man.[52]

Discriminatory and Disproportionate Effect of Nationality Law

Nationalist prejudices have affected the implementation of Dominican law. Two practices have been particularly concerning.

First, human rights groups have documented the arbitrary refusal of government officials to register children of Haitian descent as Dominican nationals. These practices were common at the Central Electoral Board (CEB) in the 1990s and early 2000s, even before the Constitutional Tribunal’s broad reading of the “in transit” exception.[53] Such cases have already been litigated in the Inter-American system.[54] Additionally, during the research for this report, Human Rights Watch found cases of Dominican mothers of Haitian descent who are still unable to register their children as Dominican nationals, despite having Dominican national husbands with no irregular or at-risk citizenship status.[55]

Second, human rights groups have documented arbitrary and racially targeted civil detention practices. Human Rights Watch documented these practices in two previous reports: Illegal People (2002) and A Troubled Year (1992). They have also been confirmed in the research for this report.[56] According to Human Rights Watch research, authorities have routinely used apparent race and ethnicity as a basis for detaining and deporting people who “look Haitian”—often without asking people for documentation.[57]

Even when the law is neutrally applied, due to their large numbers, Dominicans of Haitian descent are disproportionately affected by present legal battles concerning immigration and nationality law. As deportations increase during the summer of 2015, this distinct ethnic minority is particularly vulnerable to abuse.

II. Violations against Registered Nationals

The Naturalization Law proposed a seemingly straightforward regime to restore the right to a nationality of individuals who were already in Dominican civil registries. According to Law 169-14, such individuals would be recognized as nationals. If they already had proper nationality documents, these documents would be recognized as valid. If they did not have said documents, the Central Electoral Board (CEB) would promptly issue them.

Despite the law, Human Rights Watch documented over 120 cases where state actors continue to prevent registered nationals and their children from exercising their right to a nationality. As explained below, these cases were confirmed through a combination of direct interviews with victims and their lawyers, and a review of legal files, carried out in seven different provinces over the course of several weeks.[58]

Violations against registered nationals are characterized by the following: First, registered nationals have not had their original nationality documents automatically restored. Instead, they have been subject to an unnecessary transcription process, and put into a special civil registry, effectively creating a legally segregated citizenry vulnerable to further abuse.[59] Second, almost a year after the implementation of the law, the CEB has still not issued or validated nationality documents for many, which renders people unable to perform basic legal transactions as citizens.[60]

Moreover, despite a government commitment to halt deportations until August 2015, military and immigration officials have continually profiled registered nationals of Haitian descent and already subjected them to arbitrary detentions and deportations.

Human Rights Watch documented over 25 detentions where registered nationals were forcibly removed to deportation points along the Dominican border. In at least one case investigated by Human Rights Watch, Dominican nationals were actually deported to Haiti, despite having valid documentation.[61]

Transcription and the Creation of a Vulnerable Citizenry

Instead of fully restoring the rights of registered nationals, relying on textual ambiguities in Law 169-14, the CEB has developed an unnecessarily bureaucratic audit and transcription process, which intentionally sets denationalized Dominicans apart from other “regular” Dominicans.[62] The process needlessly consumes government resources to create a segregated citizenry, and jeopardizes the nationality rights of registered nationals.[63] Additionally, while transcription is pending, nationals’ documents are often disabled, rendering people unable to carry out regular transactions.[64]

Transcription occurs in three steps: First, the central CEB office in Santo Domingo initiates an auditing process into the nationality claim of a person in the civil registries.[65] Often, the investigation includes an in-person interview.[66] Once the person is cleared for transcription, the central CEB office sends officials to the local CEB offices at the provincial level, to physically copy existing civil registry records into separate transcription books.[67]

After transcription, a national has two birth registries: (1) an original civil registry, identical to that of all Dominicans, with a unique book, folio, and certificate number; and (2) a transcribed registry, with a different book, folio, and certificate number. This transcribed record establishes a separate juridical personality from the original civil registry.

In a number of cases, the CEB then sues to have the original civil registries annulled.[68] If the suit is successful, the original registry is annulled, and the national is then left only with this transcribed record. [69] The transcribed record can then be used to issue a new birth certificate, identification card, and passport.

As of May 2015, the CEB stated it had audited an estimated 10 million files and found over 53,000 had irregularities.[70] At time of writing, however, the CEB has not specified the total number of files that had been transcribed, nor the total number of nationality documents that had been rehabilitated for regular legal transactions.[71]

Inability to Exercise the Right to a Nationality

Transcription makes people unable to presently exercise their right to nationality. Three cases illustrate the unnecessary human costs imposed on people and civil society organizations. As all three cases show, transcription is yet another hurdle in a long line of challenges registered nationals have faced in recent years. Even when registered nationals are transcribed, Human Rights Watch findings suggest there is no guarantee they will be able to properly exercise their nationality.

|

Three Representative Cases: Karina, 35, was born in the Dominican Republic to Haitian parents, and registered as a Dominican national.[72] Although she obtained a valid identification card at 18, Karina says that when she was 24, the government refused to issue her documents necessary to enroll in university, allegedly because her claim to nationality was under investigation.[73] Unable to continue her studies, Karina began working as a chambermaid in a large beach resort, where she has been for the past 10 years. The government’s ongoing investigation has prevented Karina from getting a passport, which has limited her advancement at work. Because she has no travel documents, she has had to give up work-related travel opportunities on two occasions. In October 2014, Karina says she met with CEB officials in Santo Domingo for an interview about her transcription.[74] Karina made the two hour trip from the province of Altagracia, where she lives, to the capital. She was cleared for transcription. Although Karina needed to renew her identification card last fall, she was told she would be unable to do so until the process was finalized. Karina told Human Rights Watch that since October, she has made four separate trips to Santo Domingo to check on the status of her transcription—often having to take time off from work to do so.[75] After her last trip, CEB officials told Karina her process had been transferred to the CEB office in El Seibo, the province where Karina was born. Human Rights Watch met Karina at the CEB office in El Seibo in April 2015. Officials told Karina her transcription was still in process.[76] Because Karina has been unable to renew her identification card, she says she cannot use her medical insurance, and must pay out of pocket when she goes to the doctor.[77] She no longer has full access to her bank account or her credit card,[78] and has had trouble paying both outstanding utilities bills, and the mortgage on her house. She would also like to continue her studies, but is unable to do so given her present status. *** Dilia, 31, was born in the Dominican Republic to Haitian parents working in sugarcane fields in the province of Monte Plata. She and her husband, Euri, have eight children. Euri is a Dominican national with no problems exercising his rights as a Dominican. The seven oldest of Dilia and Euri’s children have been registered as Dominicans, without any problems. In March 2013, Dilia and Euri gave birth to their youngest child, Disaury.[79] Days after Dilia gave birth, Euri says he tried to register Disaury using his Dominican identification card and that of Dilia.[80] He was told that Dilia’s nationality was under investigation, and that he would not be able to register the child as Dominican at that time. Since then, Dilia says she has had to go to the capital at least 10 times to try to get the child registered. The trip takes over an hour each way, she says, and costs around 1,000 Dominican pesos (US$22) round-trip. Dilia says that during her visits, CEB officials have told her that she is Haitian, and needs to register the child as a foreigner.[81] She is unable to afford a lawyer, but has been so confused by the process that she has asked a non-profit legal organization for advice in the process.[82] CEB officials now tell her she is being transcribed and must wait for the process to finalize before the child can be registered.[83] In the meantime, Dilia says she cannot get health insurance for Disaury and must pay out of pocket whenever she must take the child to the hospital. Additionally, despite being together for over 16 years, Dilia and Euri have been unable to legally marry and enjoy the legal benefits of other married Dominicans. *** Ramón, 36, was also born in the Dominican Republic to Haitian migrants working in sugarcane fields. He was registered as a Dominican, and was able to get both a birth certificate and identification.[84] In 2012, Ramón was working in the spring training grounds for major US baseball teams in the Dominican province of San Pedro. That year, he had an opportunity to travel with one of these teams, the Atlanta Braves, for work. When he tried to get a passport, government officials rejected his request on account of his parents’ nationality. The following year, Ramón says his identification card was cancelled. Ramón’s supervisor was understanding, but eventually had to dismiss Ramón because of his lack of documentation. Ramón had to give up a well-paying job with health insurance and a pension, and instead began to work as a motor rickshaw driver. After months of fighting the CEB, Ramón has just been transcribed, and received a new identification card. However, the numbering on Ramón’s new card does not match the numbering on his old card. He says that when he asked the CEB official why that was, she told him “that’s how this works,” and showed him a couple of other files of individuals who had been similarly transcribed.[85] Ramón’s lawyer has told him that he needs to go back to the CEB to fix this numbering discrepancy. According to her, this could pose problems for him, given the fact that Ramón carried out a number of legal transactions under his old number. He has, for example, declared three of his five children under his old card. If he continues to use his new number and gets insurance, for instance, Ramón might not be able to have his children covered. Similarly, he may no longer have access to old pensions savings.[86] Yet Ramón is reluctant. After having fought so hard to get a new identification card, he is unsure whether it will be worth the fight for a new number. |

Ramón, Dilia, and Karina’s experiences are not isolated ones. Human Rights Watch reviewed 37 cases of registered nationals in 7 different provinces reporting similar challenges.[87]

The inability of mothers to register children was one of the most common problems interviewees reported.[88] Human Rights Watch documented a total of 59 cases of nationals unable to register due to their parents’ documentation problems.[89] In some of the most serious cases, interviewees were forced to register their children as foreigners, despite showing proper Dominican identification.[90] Numerous interviewees also reported years of being unable to go to school, or participate in the formal economy.[91]

Arbitrary Detentions and Expulsions

Beyond endless bureaucratic delays, Human Rights Watch also confirmed the detention and attempted expulsions of over 30 registered nationals in the last 6 months. Despite having proper documentation, those detained were not asked to provide identification. In some cases, despite providing documentation, victims were told their papers were not valid. Victims were only released after friends, family, and often local or international advocates intervened.

Most of those affected were Dominicans of Haitian descent, and reported that they were detained on account of their Haitian appearance. These cases highlight the risk of what registered nationals could face come August, unless the government implements proper deportation protocols.

Group Detentions

One early morning in late January 2015, local police in the town of Galván stopped a flatbed truck returning to the community of Santa Maria. On board were over 40 mourners returning from a nighttime prayer vigil. The group included five or six children.[92]

According to the truck driver, an officer took control of the vehicle without explanation and drove it to the nearby city of Neyba, in the province of Bahoruco.[93] The police did not ask anyone for their identification documents.[94]

One man, Andrés, who was in the truck that night, said the group was kept overnight in crowded quarters at the Neyba police station, with nothing to eat or drink.[95] Just past noon the next day, he said government officials drove the group over 40 miles west to the border town of Jimaní, where they were handed over to authorities of the General Directorate of Migration.

Only after a locally elected municipal official intervened did immigration authorities release the detained.[96] Immigration authorities kept victims’ identification documents, and returned the detainees to their homes.[97] Weeks later, victims were able to retrieve their documentation.

Human Rights Watch interviewed the alderman of Santa Maria, who intervened on behalf of those detained. The alderman provided Human Rights Watch copies of identification documents for those on the truck that night:[98] Of these, 27 had Dominican identification cards, 5 were children with Dominican birth certificates, 1 child on board had applied for registration under the Naturalization Law, and 3 others were Haitian migrants in the process of regularizing their immigration status.[99]

Smaller Scale Raids, Expulsions, and Detentions

Army officials have also engaged in smaller scale raids and detentions in provinces further north, as well as in Bahoruco.

On the morning of February 19, army officials detained 25-year-old Wilson near the town of Mao, in the northern province of Valverde. As Wilson was talking with friends on the side of the road, army officers drove up in a truck and asked him to show his documentation.[100]

Wilson, who was born in the Dominican Republic, asked the officers to let him get his Dominican birth certificate at his home, a couple of blocks away. The officers refused. Instead they forcibly loaded him onto the truck, along with other suspected undocumented migrants, and drove off.

Wilson was driven to several military compounds over the course of the day. Several times, he reported seeing other detainees pay bribes of 200–300 Dominican pesos (around US$4–7) to be released. He, however, did not have any money on him, or any means of communicating with his relatives and friends.

In the early afternoon, Wilson was brought to the border town of Dajabón. Along with 32 other detainees, he was counted, and ordered to walk across the border into the town of Ouanaminthe, Haiti. This was Wilson’s first time in Haiti. He had no money, no means of communication, and no form of identification on him.

Wilson was able to locate friends of friends in Ouanaminthe. With their help, he called representatives of his employer, a US-Dominican non-profit.

Wilson’s employers met him at the office of the General Directorate of Migration office at the border in Dajabón the following morning. They showed officials his birth certificate and asked that he be allowed back into the Dominican Republic. The immigration official in charge claimed that despite a valid birth certificate, Wilson was Haitian.

The official in charge refused to provide a letter granting Wilson passage through the multiple military checkpoints between the border and his home community in Valverde. Regardless, Wilson and his employer returned to Valverde, using only Wilson’s birth certificate to show to officials at checkpoints.[101]

A couple of weeks after Wilson’s temporary expulsion, in the province of Bahoruco, state officials detained Nilson, 19, and Willy, 20, both Dominican.[102]

According to the two young men, at around 7 p.m. they finished a basketball game and went into the town of Tamayo to fill up Nilson’s father’s motorcycle with gas. The young men were at the gas station when a group of officers arrived in a truck, dressed as civilians.[103] Without asking any questions, the officers grabbed the two men, and tried to force them onto to the truck. Willy resisted, and one of the officers drew a gun, while another handcuffed him.[104]

Willy said that he was forced onto the truck along with Nilson, and the two were driven to Jimaní. Like Wilson, Willy and Nilson reported seeing others pay bribes to be let go, but they did not have any money on them. As the truck drove past the community where the two young men live, they called out to friends, telling them they had been detained. [105]

Word reached Nilson’s father, Solomon, who grabbed Nilson and Willy’s nationality papers, and flagged a bus to Jimaní alongside with his wife, Rosa.[106] Solomon and Rosa arrived at around 10 a.m. the following morning. Along with some local immigrant rights advocates, they went to the military base where the Nilson and Willy were being detained. They were released after officials saw Nilson’s identification card and Willy’s birth certificate.[107]

Human Rights Watch also documented the detention of four other young men, ages 18, 19, 21, and 21, near the community where Nilson and Willy live.[108] According to Emmanuel and Martin, on March 14, 2015, army officials detained them and two friends, Pablo and Johncito, on the side of the road during an immigration raid near the community where they live. Emmanuel, Martin, and Pablo were registered nationals. Johncito was born in the Dominican Republic and is in the process of getting registered. They were not asked for identification documents and were presumably detained on account of their “Haitian” appearance. The young men were not forcibly removed from their community, as Emmanuel’s father intervened before they could be transported.[109]

III. Violations against Unregistered Nationals

The Naturalization Law also provided an administrative process to register nationals. To register, individuals had to prove they were born in the country and provide identification for their parents. The Ministry of Interior and Police (MIP) has been in charge of implementing the process, and reviewing applications.

Unregistered nationals also continue to be deprived of their right to a nationality.

First, the process has forced thousands of Dominicans, mainly children, to enter the civil registries as foreign nationals first.[110] These applicants have eventually been promised Dominican nationality through a naturalization process devised for foreigners, which does not grant the same rights as other Dominicans. Moreover, the registration process has incorporated burdensome documentary requirements impossible for many to meet—especially during the brief registration period. Though the law has affected mostly children, the government has offered limited resources for implementation, and instead delegated much of the responsibility to civil society organizations.

According to official government numbers, over 44,000 Dominicans have been unable to register.[111] That is, only one in five eligible to register were able to do so. These left out of the law now face an uncertain legal limbo. Civil society groups estimate those unregistered may be higher.[112]

Additionally, like registered nationals, unregistered nationals have been subject to arbitrary detentions and expulsions—in many cases while trying to register.

Nationals Become Foreigners

As noted in Section I, the registration process has raised concerns under international human rights law.[113]

The process has been divided into three phases: First, a registration period that ran for 180 days from late July 2014 through early February 2015.[114] As noted above, at the end of the registration period, MIP officials reported that 8,755 applications had been received.[115] The actual number of successful registrations will likely be smaller, given that government officials have reported many incomplete applications.[116] After the MIP gives a total number of applicants successfully registered, they will have 60 days to “regularize” their status as foreigners.[117] Finally, two years after they regularize, applicants will have the opportunity to naturalize, and gain full rights as citizens.[118]

The government promised applicants an answer within 30 days of a completed registration application.[119] At time of writing, however, the government has not confirmed the successful registration of a single applicant.

It is still unclear whether and how applicants will regain full rights as Dominican citizens. Because individuals are to acquire citizenship through a regularization and naturalization process under Dominican law, according to legal experts, the process raises technical questions.

Under Dominican law, naturalization requires that applicants have a foreign identification document, such as a passport.[120] However, no one who applied to the Naturalization Law has a foreign passport, because they are Dominican nationals. Moreover, the naturalization process is discretionary, contingent on the executive power’s approval at the time of naturalization.[121] Thus, even those people who do manage to register under the Naturalization Law will be subject to the discretion of the president at the time they choose to naturalize. Even if naturalized, these individuals will not have the same rights as full Dominicans.[122]

Additionally, nationalist groups have already challenged the constitutionality of the registration process before the same Constitutional Tribunal that created the denationalization crisis in 2013.[123] If this suit is successful, applicants to the registration process may find themselves newly denationalized, making the whole registration process void.

Onerous Documentation Requirements

The registration process has also imposed burdensome documentation requirements on applicants that were hard to meet within the application window.

Human Rights Watch interviewed representatives from 11 civil society organizations across the country who helped complete registration applications. Collectively, these organizations reported they handled 4,026 cases, nearly one of every two applications submitted to the MIP by February 2015.[124]

Restrictive Documentation Requirements

The Dominican government enacted more restrictive documentation requirements under the final decree 250-14 as compared to the draft decree.

|

Final Decree 250-14 |

Draft Decree 250-14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

According to civil society organizations, applications were difficult for families to complete on their own, particularly given the need for legal guidance, and the extremely short implementation period.[125] Two documentation requirements made the applications particularly challenging: the need for parental identification, and the limited evidentiary proofs accepted to establish the applicant was born in the Dominican Republic.

Parental Identification Requirement

Though not specified under the decree implementing the Naturalization Law, the MIP required applicants to provide parental identification. This requirement was stated in an instructional manual distributed to MIP officials implementing the law.[126] Human Rights Watch also confirmed the requirement with MIP officials.[127] While the MIP instructional manual suggested that either the father or the mother’s identification would suffice, government officials and civil society groups told Human Rights Watch that in practice, it was often the mother’s identification document that was required.[128]

Mothers of many children of Haitian descent, however, lacked documentation at the outset of the process, and were unable to get it within the 180-day registration period. This was the case with Ana Iris, 16, and Luis Mario, 11, two siblings born and raised in the outskirts of Santo Domingo.[129] Although both wanted to register, their mother, Maria, was unable to obtain proper identification in time. Maria says she applied for an identification card from the Haitian consulate in November 2014. However, she did not receive her card until April 2015, well after the end of the registration period. Ana Iris and Luis Mario were thus permanently banned from applying for Dominican nationality papers. They have been told at school that if they do not have proper documentation, they may not be able to return next year.

Organizations registering applicants explained that cases like that of Ana Iris and Luis Mario were common. In the province of San Pedro, for instance, the firm of immigration lawyer Noemi Mendez successfully registered 225 applicants.[130] Mendez and her staff, however, identified over 140 applicants whose parents did not have proper documentation at the outset of the process.[131]Of these, Mendez reported that fewer than 20 were able to get documents from the Haitian government in time to register.[132] At the Centro de Desarrollo Sostenible (CEDESO), lawyers completed 221 applications in the province of Bahoruco.[133] An additional 348 applications were not completed because of the lack of maternal documentation.[134] Although CEDESO accompanied 43 women to get proper documents, none were able to get these documents in time for their children.[135]

In interviews with unregistered nationals and local advocates, Human Rights Watch documented over 60 cases where applicants did not have appropriate parental documentation to complete the process. Interviews were conducted in 7 provinces around the country, mainly with parents of children who could not register.[136] In a few cases, Human Rights Watch only spoke to local advocates and reviewed their files.[137] In over 30 of these cases, parents tried to get documents from the Haitian consulate, but were unable to do so in time. In other instances, parents either did not know how to apply, did not have the money to do so, or did not have the time to do so before the registration process closed. In three or four cases, mothers had passed away, and children were unable to get a death certificate.

Women seeking to register their children reported that getting documents at the Haitian consulate was slow, difficult, and expensive.[138] Between August and September 2014, for instance, the Asociación Scalabriniana al Servicio de la Movilidad Humana (ASCALA) accompanied over 270 people to get documents at the Haitian consulate.[139] As of April 2015, ASCALA representatives told Human Rights Watch that none of these individuals had received documents.[140] Local press and civil organizations seeking to document people reported similar delays in obtaining Haitian identification.[141] To further complicate matters, the Haitian government only operated one documentation office out of Santo Domingo until April 2015.[142] Though it initially charged people 2,500 pesos ($55) for documents, that cost was later reduced to 1,000 pesos ($22).[143] This did not include bus fares, which, depending on the province, could easily add another 1,000 pesos ($22) for a round trip, and required women to take time off work, or other economically productive activities.[144]

Given these delays, many unregistered nationals were excluded from the process altogether, in many cases solely on the basis that their mothers were unable to obtain proper documentation. Advocates working for one particular organization providing legal support to applicants were able to complete almost 10 percent of the applications submitted during the registration period.[145] They told Human Rights Watch that given the time constraints imposed by the registration period, they were unable to complete many applications. They said that they had to summarily turn away applicants who did not have maternal documentation at the outset of the process, because they knew it would be almost impossible to get this documentation in time.[146]

Limited Evidence to Prove Birth in the Dominican Republic

Beyond the maternal identification document, applicants were required to prove they were born in the Dominican Republic before April 18, 2007.[147]

Early versions of the decree implementing the registration process proposed more flexible methods of proving birth in the country, which were dropped during the consultation process.[148]Pursuant to the final decree, applicants had to show one of four types of proof that they were born in the country: (1) a hospital birth record; (2) a notarized statement signed by seven witnesses, testifying to the applicant’s birth date and place; (3) a notarized statement by the midwife delivering the applicant; or (4) a notarized statement by family members of the applicant with Dominican nationality.[149]

In 5 separate provinces, Human Rights Watch spoke with children and their families to document 33 cases of applicants left out of the process.[150] Interviewees repeatedly reported difficulties in accessing hospital records and completing the notarization process within the registration period.

In October 2014, for instance, Elmise says she applied for hospital records to register two of her boys, William and Christopher, using her Haitian birth certificate, in the province of El Seibo.[151] While the hospital provided Christopher’s records in time, it did not provide William’s until after the February 2015 deadline. Because of the hospital’s delay, Elmise was unable to register him.

Similarly, Sani tried to register her son Jonelson, 12, using his hospital records. Although Sani did get the records in time, due to discrepancies between the spelling of her name on the records and on her official identification, she says the registration office would not accept the application.[152] Such spelling discrepancies are common in the records of migrants and their children, given the translation that often happens between Haitian Creole and Spanish. Neither Sani nor Elmise had Dominican family to make a statement on their sons’ behalf, nor did they have time to complete the notarized act with seven witnesses.

In practice, many had to turn to notarized acts to meet the evidentiary proof.[153] Yet this was a lengthy process.[154]

First, the applicant (or a parent) had to find seven witnesses with valid Dominican identification cards who could testify to the applicant’s birth in the country, and who could read and write. The applicant then had to get copies of all seven Dominican identification cards and take these to a notary public, who would draft the notarized declaration. All seven witnesses would then sign the declaration, as would the notary. Once signed, the declaration was taken to the local town hall, where it was registered, and returned to the notary public. The notary public would keep a copy of the original declaration, and draft a second certification for the declaration (in Spanish, a “compulsa”). This certification was taken to the local Attorney General’s Office where it was legalized and returned to the notary. The applicant then proceeded to the Ministry of Interior and Police with copies of the identification cards of the seven witnesses, a copy of the notarized declaration, and the original certification of the declaration, as well as the maternal identification document.

While this was easier in urban centers, it was challenging for applicants living in rural, largely migrant communities. Applicants often had difficulties finding sufficient witnesses, and then had to travel long distances to reach the town hall in the provincial capital. In several provinces, applicants had to travel to neighboring provinces to reach the nearest Attorney General’s Office.[155] Additionally, despite a promise by the government to open a registration office in every province, over a third of these offices never opened.[156] Similarly, the government never created any of the “mobile” offices it promised applicants.[157]

Notarized declarations, and applications generally, were difficult for many applicants to complete without guidance.[158] Unable to afford lawyers, they relied on civil society organizations for support—many of whom did this work for free and on a volunteer basis.[159] Moreover, in many communities, it was these organizations that informed residents about the existence of the law in the first place.[160]

Yet civil society organizations were stretched thin, and could not complete all the cases they identified within the registration period. The Centro Bonó, for instance, completed a total of 31 cases in La Romana, yet reported they were unable to complete another 45.[161] As noted above, for example, lawyers at the Centro de Desarrollo Sostenible, completed 221 applications. For lack of time, however, they were unable to complete another 17 identified cases.[162]

As local organizations explained to Human Rights Watch, even though they began working in the fall of 2014, they were still identifying new cases in the final weeks of the registration period.[163] Many children who did not already have their documentation process well under way before January, were hard pressed to meet the registration deadline.[164]

Arbitrary Detentions and Expulsions

Beyond the bureaucratic hurdles, Human Rights Watch documented the deportation, detention, and harassment of over 50 people trying to go through the registration process. Most were detained at checkpoints as they traveled to government offices to deliver their registration applications. One group was deported to Haiti. Government officials also entered at least one registration office to try and deport people as they were handing in their applications. Officials only backed down when civil society groups intervened on victims’ behalf.

Group Expulsion of Children Applying for Registration

On January 27, 2015, two Catholic nuns in the province of Elías Piña organized a group of 33 children to register under the Naturalization Law.[165] Mothers of several of the children accompanied them. The group was traveling on two buses specifically chartered for the purpose of transporting the group to the nearest registration office in San Juan de la Maguana.[166]

According to Sister Yomaris Polentino, who accompanied the children, at around 8 a.m. army and immigration officers stopped the buses at a military checkpoint in Matayaya. Checkpoints are common along major roads in the country’s western provinces as a way to detect and detain undocumented migrants.[167]

Sister Yomaris said that the army and immigration officers told her that the buses did not have authorization to travel. The nuns showed the officers the children’s applications for the Naturalization Law, and explained the purpose of their trip.

The officers told the group both buses had to travel to the border town of Comendador, to receive proper authorization. According to Sister Yomaris, when the groups arrived there, however, officials told her the children were going to be deported. According to Sister Yomaris, the officers falsely claimed the children had been found wandering the streets without proper documentation. In fact, they had been on a bus with Sister Yomaris.

Around 2 p.m. on January 27, the entire group was deported to Haiti, and forced to spend the night on the Haitian side of the border. Sister Yomaris stayed in the Dominican Republic to sort the situation out while her colleague, Sister Isabel, spent the night with the children.

Only after repeated interventions by a number of local politicians and the Ministry of Interior and Police did the military allow the children back into the country to register under the law. The group re-entered the Dominican Republic early on the morning of January 28.

Even with officials from the Ministry of Interior on board the buses, the group was repeatedly detained at checkpoints between the border town of Comendador, and the registration office in San Juan de la Maguana. The group finally arrived at the office in San Juan around mid-afternoon.

Additional Checkpoint Detentions

Three days after the detentions in Elías Piña, army officials detained a bus with 16 applicants for re-nationalization in the province of Independencia.[168] On board the bus were also two staff members from the Jesuit Migration Service (JMS), a Catholic non-profit, who were accompanying the children in the process.

The group was leaving the town of Jimaní for the closest registration office, located about two hours away in Barahona. The group had been to the Barahona office the day before, and had been asked to return the following morning because of the office’s large caseload.

According to JMS staff, between 7 and 8 a.m., military officers stopped the bus at the first checkpoint right outside of Jimaní, and told the driver to return to the migration office in Jimaní. There, JMS staff explained the purpose of the trip. The supervising officer, Ovidio Dotel, refused to accept the explanation, and accused JMS staff of smuggling people into the Dominican Republic.

JMS staff told Human Rights Watch that the director of the Barahona office called Dotel to explain the situation to him, but Dotel refused to let the group go. The group was detained for six hours. They were only released after the intervention of several community leaders, including the governor of the Independencia province, the bishop of Barahona, and the head of the national office for the Naturalization Law. The group eventually reached the Barahona office.

Attempted Raid in Barahona

On January 22, Lidio and Esteban accompanied two separate groups of people to get registered in Barahona. The two men are community leaders in region, and worked with local organizations to help register people.[169] They were each at the Barahona office with around 15 to 20 applicants that day.

According to Lidio and Esteban, at around 3 or 4 p.m., military and migration officers entered the registration office, and detained the applicants, threatening to deport them.

As Lidio describes it, “the children were crying and screaming, running outside to hide behind the vehicles.”[170] When he tried to intervene, the officer in charge told Lidio “you have no right to butt in here, you’re a negro [black man].”

The supervisor at the Barahona registration office stepped forward and explained the situation to the officers. This gave Esteban time to finish the registration process and leave with his group. The officers, however, kept harassing Lidio and those with him. Lidio said that the officers from the registration office eventually took him and his group back to their vehicles and allowed them to return home.

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Celso Pérez, Gruber Fellow at Human Rights Watch. It was edited by José Miguel Vivanco, Americas Division executive director at Human Rights Watch; Danielle Haas, senior editor in the Program Office; Aisling Reidy, senior legal advisor; Bill Frelick, Refugee Rights Program director; Amanda Klasing, Women’s Rights Division researcher; and Michael Bochenek, Children’s Rights Division senior legal counsel. Health and Human Rights Program senior associate Jennifer Pierre provided research assistance. Americas Division associates Nina Elizondo, Kate Segal, and Meagan Mszyco contributed to research logistics and production. Americas Division interns Hope McKenney and Christine White provided research support. Fitzroy Hepkins and Jose Martinez provided production assistance. This report was translated by Gabriela Haymes.

Human Rights Watch would like to thank the numerous organizations and individuals that contributed to this report. We are very grateful for the support provided by the Bonó Center (Centro Bonó); the Socio-Cultural Movement for Haitian Workers (Movimiento Socio-Cultural de los Trabajadores Haitianos); the legal office of Ms. Noemi Mendez; the Scalabrini Association for the Service of Migrants (Asociación Scalabriniana al Servicio de la Movilidad Humana); the Center for Sustainable Development (Centro por el Desarrollo Sostenible); the Center for Formation and Social and Agrarian Action (Centro de Formación y Acción Social y Agraria); the Jesuit Migration Service (Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes); the Yspaniola Foundation (Fundación Yspaniola); the Congregation of the Daughters of Jesus (Congregación Hijas de Jesús); Dominicans for Rights (Domincan@s x Derecho); the Caribbean Migrants Observatory (Observatorio Migrantes del Caribe); Frontier Solidarity (Solidaridad Fronteriza); the Movement of Dominico-Haitian Women (Movimiento de Mujeres Dominico-Haitianas); and the Open Society Justice Initiative. We would like to thank the leaders of Reconoci.do, especially Ana Maria Belique, Germania René, Rosa Iris Diendomi Alvares, Juan Alberto Antuan, Franklin Yaqué, Epifania St Charls, Juan Telemín, Jairo Polo, and Estefany Feliz Pérez, for their invaluable support in contacting and arranging interviews with victims.

Human Rights Watch would also like to thank the following individuals for their feedback on various drafts of the report: Marie-Claude Jean Baptiste, program director at the Vance Center; Wade McMullen, staff attorney at the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights; Kavita Kapur; Paola Pelletier; Juan Carlos González, sociologist and researcher at the Caribbean Migrants Observatory.

Human Rights Watch is deeply grateful to victims and their family members who shared their testimonies with us. Human rights violations inflict wounds on victims and their families, and recounting such stories can be painful. Many of the victims who spoke with us expressed hope that by telling their stories, they could help prevent others from suffering the same abuses.