(Kinshasa) – Democratic Republic of Congo authorities have failed to fully investigate the killing of at least 66 Indigenous Iyeke people in the Bianga district of Monkoto territory in February 2021, Human Rights Watch said today. Congo’s National Assembly voted during 2021 for a law that would for the first time protect and promote Indigenous peoples’ rights, but the bill remains stalled in the Senate.

From February 1 to 3, 2021, hundreds of ethnic Nkundo assailants killed several dozen Iyeke villagers, including at least 40 children, 22 men, and 4 women, and wounded many more in eight villages. The assailants also burned down more than 1,000 houses as well as schools, churches, and health centers, according to survivors, witnesses, civil society groups, and provincial officials. The authorities initially opened an inquiry but did no field investigation. A year on and no one has been charged for the killings, which have gone largely unreported in the media. Two people were tried and acquitted on lesser charges and the case closed.

“The silence surrounding the horrific killings of Iyeke villagers and lack of accountability highlight the longtime discrimination against Indigenous people in Congo,” said Thomas Fessy, senior Congo researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The Congolese authorities should acknowledge the failure to prosecute anyone for murder, and fully investigate and fairly prosecute all those responsible for these massacres.”

The Human Rights Watch findings are based on an October 2021 research trip to the western Monkoto territory. Human Rights Watch interviewed 44 people, including Iyeke survivors and witnesses to the attacks, Nkundo villagers, judicial officers, civil society activists, members of parliament, provincial officials, and military personnel.

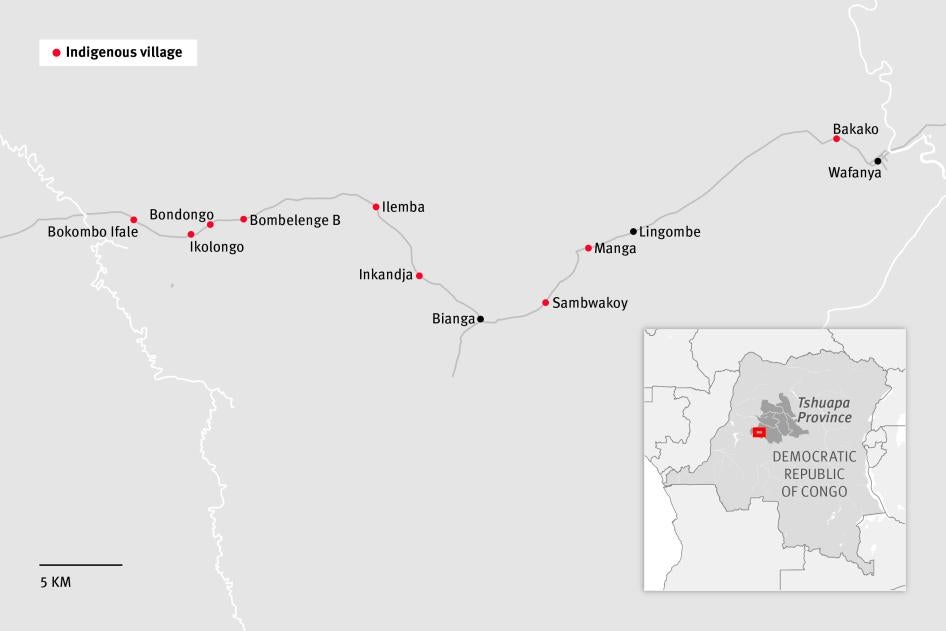

Indigenous Iyeke people – part of the larger Batwa Indigenous group – and ethnic Nkundo live in separate but neighboring villages dotted along a 100-kilometer stretch forming the remote Bianga district on the edge of the Salonga National Park, Africa’s largest tropical rainforest reserve, in Tshuapa province. Longstanding tensions between the two groups revolve around access to land and bonded labor.

On January 31, 2021, a scuffle broke out in the Indigenous village of Manga between an Nkundo coffee trader and an Iyeke villager over a debt, and the trader reportedly vowed revenge. The next day, scores of Nkundo villagers stormed Manga, looting and burning down dozens of houses, resulting in the deaths of two toddlers.

Several witnesses said many attackers’ faces were painted in charcoal, and that they wore red headbands and black-string bracelets around their wrists as protective amulets. Some were armed with hunting rifles locally known as “Calibre 12” or “Baikal,” while others carried machetes, knives, and spears.

A 66-year-old man described the loss of his 3-month-old granddaughter. “My daughter had twin babies,” he said. “She suddenly realized [that one] was missing while we were running away but we couldn’t go back because they were shooting.” He said that three days later, when they briefly came out of the forest to check on the situation, they found the baby girl’s charred body.

On February 2 and 3, armed Nkundo men simultaneously attacked seven other Iyeke villages, looting and burning houses, churches, health centers, and schools. Witnesses and official sources said at least one automatic weapon was used during the attacks. Some of the wounded later died in the forest.

A 55-year-old woman from Sambwakoy village said she and her husband were returning from the fields when he was killed. “He fell to the ground right outside our house,” she said. “He was struck by bullets in the face and in the chest.”

When the attacks began, many young children including toddlers found themselves on their own, as their parents were working in the fields. The assailants did not spare them. Out of the 40 children killed, 33 were under age 10, according to lists compiled by Monkoto territory officials.

The attacks caused more than 8,000 Iyeke to flee into the forest, where most remained for at least six months. Provincial authorities and members of the national parliament distributed cash assistance following the attacks, including some payments for loss of life. The assistance provided was inadequate to redress the losses suffered, Human Rights Watch said.

The massacres occurred during escalating tensions between the Nkundo and Iyeke communities following the unresolved killing of an Iyeke laborer on December 29, 2020, near the village of Bondjindo. His body was found mutilated in an Nkundo-owned agricultural field. Iyeke villagers reportedly suspected the landowner’s family and looted and burned their home in retaliation.

Human Rights Watch reviewed a March 2021 parliamentary report that noted that local authorities “didn’t show any concerns for the deteriorating security situation in Bianga district … as if nothing was happening.”

The government response to the Bianga massacres has been wholly inadequate, Human Rights Watch said. On February 16, the Congolese military deployed seven national army soldiers to secure this vast district with no transport or means of communication.

On April 23, the authorities arrested seven men in connection with the killings, five of whom were eventually released. Three judicial officers said that the police commander of Bianga district was suspected of involvement in the attacks but his whereabouts remain unknown. In late December, a court in Boende acquitted both Nkundo defendants in a hasty trial in which no Indigenous survivors of the massacre were present.

Several officials have alleged that provincial politicians attempted to stall or close the inquiry, preventing the criminal investigation from moving forward to protect those responsible.

A 52-year-old Iyeke father of six hosting four people displaced by the massacre said that “peace will not return until those who attacked us are disarmed and arrested. We fear that they will exterminate us – next time it will be worse.”

Congolese authorities have an obligation to fully and fairly investigate the Bianga killings and bring those responsible to justice, Human Rights Watch said. To ensure that the investigators have adequate resources, the government should request technical support, including logistical and forensic assistance, from the United Nations Joint Office for Human Rights. The government should reinforce security in the area with well-trained police. It should provide, with international assistance, necessary health care and mental health support to survivors. The government should also work with humanitarian agencies to repair and rebuild homes, schools, and health centers.

Congolese lawmakers should adopt measures to recognize and protect Indigenous peoples’ rights in line with international standards, Human Rights Watch said.

“One year since the massacres, Iyeke families live in fear of the assailants who roam free,” Fessy said. “The government needs to prosecute those responsible for these horrific crimes, but also pass legislation to ensure that Indigenous people are no longer effectively second-class citizens.”

For additional details and accounts, please see below.

Discrimination Against Indigenous Peoples in Congo

Congo has an estimated 700,000 to two million Indigenous people, according to government figures and civil society groups. Their communities live a semi-nomadic life based on a deep connection to the forest within the Congo Basin. They are hunter-gatherers who have depended on the forest ecosystem for millennia, with their lives and culture closely linked to the rainforest and its resources.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights refers to Indigenous peoples as “those particular groups who have been left on the margins of development, who are perceived negatively by the dominant mainstream development paradigms and whose cultures and lives are subject to discrimination and contempt.” They often live in inaccessible regions and suffer from various forms of marginalization, both politically and socially, and domination and exploitation.

Indigenous peoples in Congo have long suffered stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination, including social exclusion, segregation, disenfranchisement, and violations of their human rights. They experience poor access to services such as health and education.

The rights of Indigenous people in Congo are protected by international and regional standards, but the Congolese government has long ignored their customary rights. They have been forcibly evicted and displaced from forests as result of historical expropriation of Indigenous lands for conservation and logging without compensation, disrupting their livelihoods and violating their rights to land, culture, and self-determination.

“Before [the Bianga killings], we cohabitated but [the Nkundo] would consider us like animals,” said an Iyeke man from Manga village. “We can’t eat together, and they wouldn’t touch our food, but we plow their fields, and we do construction work for them.”

Several Iyeke villagers said the Nkundo do not allow mixed marriages. “They still come and flirt with our daughters, but if we flirt with theirs, they would kill us,” said a villager in Sambwakoy.

Indigenous peoples have remained under threat throughout the country and there have been recurring lethal attacks against them. “Three of our teachers are Bantu from Lingombe who attacked us,” an Iyeke man from Manga said. “Our children fear their teachers now. We need our own school.”

Indigenous peoples in Congo have historically been referred to as “pygmy people,” a pejorative term that etymologically points to their short stature. Even though the term is still often used in a condescending way, Indigenous peoples’ groups have in recent years approved the concept to unify around their common challenges that characterize their plight and their treatment by non-Indigenous communities, commonly referred to as Bantu.

A Nkundo man from Wafanya described the relationship with the Iyeke: “According to our traditions, we are their masters, and our customs impose segregation. We can pray together and attend the same schools, but we can’t marry them or eat together. They are our servants but not by force.”

He said Indigenous people were “seeking social equality, which is causing conflict.”

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples provides that Indigenous peoples have both individual and collective rights. Indigenous peoples “have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired.” They are “free and equal to all other peoples and individuals and have the right to be free from any kind of discrimination, in the exercise of their rights, in particular that based on their indigenous origin or identity.”

States have a responsibility to provide mechanisms to prevent and provide redress for actions that dispossess Indigenous peoples of their lands, territories, or resources, as well any form of propaganda designed to promote or incite racial or ethnic discrimination directed against them.

Since President Felix Tshisekedi took office in 2019, the Congolese government has committed to advance the rights of Indigenous peoples, including by adopting a specific law. Parliament adopted a Bill on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Indigenous Pygmy Peoples in April 2021, but it has since stalled in the senate.

The bill acknowledges that Indigenous peoples’ “living conditions are characterized by discrimination, stigmatization and many other forms of abuse which are the basis of political, administrative, economic, social and cultural marginalization.”

The legislation if adopted would “in particular, guarantee” Indigenous peoples “recognition of [their] traditions, customs and legal pharmacopoeia,” “easier access to justice and basic social services,” and “the right to lands and natural resources they own, occupy or use, in accordance with the law in force.”

Congolese senators should urgently enact the proposed legislation and the government should take the necessary steps to put the law into effect, Human Rights Watch said.

The Bianga Killings

On February 1, 2021, scores of ethnic Nkundo from Lingombe village attacked the neighboring village of Manga. An Iyeke resident described the attack: “It was like a whole village attacked us with rifles. We were so overwhelmed that we fled. They looted and burned everything, including our solar panels and batteries, even our electoral cards. We ran into the forest.”

Traces of the attack were evident when Human Rights Watch visited Manga in October. Dozens of houses were totally or partially destroyed while walls still standing were charred.

A survivor said that his 8-month-old daughter died during the attack. “My wife was carrying our baby girl while we were running to flee,” he said. “But she fell and broke her neck.”

The assailants burned at least 244 houses and a church in Manga, according to official provincial records. At least 17 people were injured. Provincial records showed no death toll in Manga, but Human Rights Watch confirmed the deaths of at least two toddlers, including the 8-month-old girl.

Manga residents said the attackers looted the primary school but did not burn it because three of the teachers were Nkundo.

On February 2 and 3, Nkundo attacked the Iyeke in the villages of Sambwakoy, Bondongo, Ilemba, Bakako, Bombelenge B, Ikolongo, Inkandja, and Bokombo Ifale. The assailants systematically looted property and burned about 1,000 houses, 7 schools, 3 health centers, and 5 churches, according to official records and civil society reports.

The Nkundo attacked the villages with traditional hunting rifles, machetes and spears, and at least one automatic weapon. Most of the victims were children and the elderly, who could not flee the assaults.

Some Iyeke reportedly tried to defend their villages with bows and poisoned arrows but with little effect.

The largest numbers of killings were in Sambwakoy, Bondongo, and Bombelenge B, where death tolls respectively reached at least 20, 22, and 18 people, according to official records and civil society reports.

Official provincial records say three Nkundo were also killed during the violence. However, several Nkundo, judicial sources, and activists said that no Nkundo died in those three days. The March parliamentary report also stated that “no dead” had been registered among the Nkundo.

Sambwakoy

On February 2, Nkundo assailants attacked Sambwakoy village, home to about 3,800 Iyeke. Witnesses said some of the attackers had painted their face with charcoal and were wearing red headbands as well as black string around their wrists as a protective amulet.

The attackers killed at least 20 villagers, including 14 children under age 10, according to witnesses and official records. The attackers burned at least 246 houses, a church, and 2 schools, and pillaged the health center.

A survivor said he was shot and wounded but managed to escape to the forest:

I had just arrived back home when I heard screams outside, some people were shouting “The Nkundo are attacking us! They are killing us!” I came out of the house to see what was going on, and I was shot from a caliber-12 hunting rifle. I screamed. Bullets had hit my face, my right knee and thigh, and my abdomen.

He said he did not know where his wife and children were. “I could see a group of Nkundo firing, but I didn’t see who shot at me,” he said. “If I stayed lying on the ground, they would have killed me, so I fled to the forest and lied down somewhere else. Other Indigenous people found me by following my bloody trail.” Those who rescued him reunited him with his wife and children, who had fled to the forest, three days later.

One man said that the Nkundo beat him and forced him to walk alongside the attackers. “They put my arms up and tied them with a rope,” he said. “They beat me and hit me with a machete and a spear.” Scars of his wounds were visible on his back and his leg. “They forced me to follow them while they were burning houses and shooting at people,” he said:

They burned the [main] church, and then we went to the health center. The guard was hiding behind [the building] but they shot him dead. Then, they entered a house and found [a man] inside, they forced him out the back. A young man hit him in the head with a machete and others shot him in the chest. He dropped dead. When we got to another church, they shot and killed someone else and left them there.”

The attackers deliberately burned alive an older woman in her house. The man forced to walk with the attackers said, “Toward the other end of the village, they stopped in front of the nurse’s house and saw that his mother was still inside. She couldn’t move on her own. They shut the doors, poured gasoline over the house and lit it on fire.”

He said he thought the attackers would eventually kill him: “Before leaving the village, their leader told me: ‘We wanted to kill you and throw you in the river, but you are lucky.’ They untied me and let me go.”

The attackers did not spare children.

“Later in the day, when it was quieter, some of us came back to the village for a moment,” a witness said. Pointing to the doorstep of a house, he recalled finding the small bodies of two siblings: “The two sisters were lying right here. The baby girl, who was only a few months old, was hit by several bullets on her right flank. Her sister, age 2, had a bullet stuck in the throat. We buried them both behind the house.”

Survivors said that some of the wounded died in the forest, where they were buried.

Perspective of Nkundo Villagers

On October 16, Human Rights Watch met with a group of about two dozen Nkundo villagers in Lingombe to discuss their involvement in the February attacks. They turned down a request for individual interviews.

The villagers did not deny the attacks but blamed the Iyeke for a series of “provocations,” including the incident that led to the scuffle in Manga on January 31. Some also accused the Iyeke of killing cattle belonging to the Nkundo. “We had no option but to fight,” one said.

“We saw that they had poisoned arrows and we thought we may die so we burned their houses,” another man said. He said that they could not have used rifles because they “didn’t have any,” causing an uproar from others in the group who realized his statement was not credible.

“We do have a few hunting rifles, but we didn’t use them,” one man said. “We used machetes because [the Iyeke] were using machetes too. Indigenous people like to tell stories, but it is not true.”

National army soldiers deployed to secure the area said that they “had not been instructed to disarm the assailants” even though they acknowledged that hunting rifles and an automatic weapon had been used during the attacks. “When our mission is over, there will be more incidents,” the patrol commander said. “The government must approach [both communities] so they stop the conflict.”

Inquiry and Political Interference

The March parliamentary report noted that “manipulation” of both communities by politicians in the last decade had led to “a climate of defiance [and] intolerance between the Bantu [Nkundo] and Indigenous Pygmy people in the district of Bianga.”

The report said, “This supports the thesis of the existence of a political hand at the origin of the current conflicts.” It concluded that there were “actors pulling the strings who [were] manipulating both communities with the aim of benefiting from their support in the upcoming 2023 elections.”

Justice authorities in Boende, the Tshuapa provincial capital, said that an inquiry into the killings began shortly after the attacks. Two Nkundo suspects were tried for arson, conspiracy, and pillaging in late December, according to one of their lawyers. Indigenous survivors of the attacks were not present at the trial. Both were acquitted.

The authorities have carried out no investigations on the ground. They said they lacked the means to reach the area, more than 200 kilometers south of Boende. Cut off by the Luilaka River in the equatorial forest, the Bianga district is only accessible on motorbikes and by dugout canoe and has no phone network coverage.

Military justice authorities in Boende said that the police commander of Bianga district was suspected of involvement in the attacks and that they had tried to locate him, but that his whereabouts remain unknown.

Two judicial officers along with civil society activists said that beyond the logistical obstacles to field investigations, provincial and local politicians have directly interfered with the case.

“There’s an attempt to cover this up, it’s very serious,” a judicial officer said. “Some provincial actors, including members of the [provincial] parliament, want to control the justice system … they’ve politicized justice.”

“Up to 80 people should have already been questioned but it hasn’t happened yet because of political interference,” said another judicial officer. “This case is being slowed down by politicians.”

An activist said that “some provincial MPs [members of parliament] [were] doing everything to bury this case,” because as Bantu, like the Nkundo, they were willing to protect them.

Several Iyeke witnesses said some Nkundo chanted during the attacks: “The Honorable [member of parliament] told us to kill the Iyeke – they will explain themselves” (in Lingala: “Honorable, apesa biso mitindo toboma Iyeke, ye moko okosamba”).

A credible investigation into the Bianga killings should determine whether local or provincial leaders played a role in the attacks, Human Rights Watch said. Those found to have been involved should be fully prosecuted.