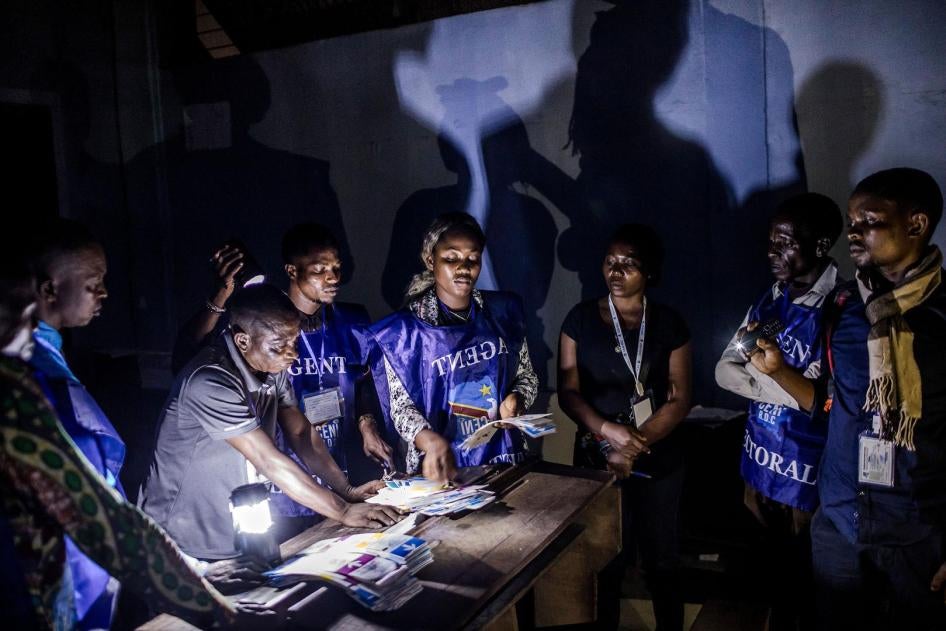

(Kinshasa) – Widespread irregularities, voter suppression, and violence significantly marred elections on December 30, 2018 in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Election officials should ensure that the announced results in the presidential, legislative, and provincial elections are accurate.

More than a million Congolese were unable to vote when voting was postponed until March 2019 in three opposition areas. Other voters were unable to cast votes because of the last-minute closure of more than 1,000 polling stations in the capital, Kinshasa, problems with electronic voting machines and voter lists, and the late opening of numerous polling places across the country. People with disabilities, or who are elderly or illiterate, faced particular difficulties at polling places or using the voting machines, which had never before been used in Congo. Election observers were also denied access to numerous polling stations and vote tabulation centers.

Official election results that suggest a falsified count could generate widespread protests, raising grave concerns of violent government repression, Human Rights Watch said.

On December 31, the government shut down Internet and text messaging throughout the country, as it has done numerous times over the last four years to restrict independent reporting and information sharing. It also cut the signal for Radio France Internationale (RFI) in Kinshasa and other cities, and withdrew the accreditation for RFI’s special correspondent in Congo, who had to leave Congo on January 3.

“Congolese voters showed they were determined to participate in the democratic process in the face of rampant election-day obstacles,” said Ida Sawyer, deputy Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The authorities should immediately restore all communications, allow independent media outlets to operate freely, and ensure that the vote count is carried out in a credible, transparent manner.”

Congolese authorities had delayed elections repeatedly for over two years, permitting President Joseph Kabila to remain in office beyond his constitutionally mandated two-term limit, which ended on December 19, 2016. Preliminary results are to be announced by January 6, although the president of the national electoral commission (CENI) said it might not make this deadline. Official results are expected by January 15, and the new president is to be sworn in on January 18.

The Human Rights Watch findings are based on incidents documented by more than 40 Congolese human rights activists deployed across Congo during the campaign and on election day, and verified by Human Rights Watch staff in the country, as well as reports by Roman Catholic Church observers, journalists, and others.

State security forces, armed groups, and militias in eastern Congo’s North Kivu province intimidated voters to coerce them to vote for specific candidates, particularly for the ruling coalition’s presidential candidate, Emmanuel Shadary, and for ruling coalition candidates for parliament. In Maniema, police chased voters from polling stations, in some cases after people protested that they could not find their names on the voters’ roll. A high-level government official in Kalima prevented opposition supporters from entering a polling place.

Violent clashes involving voters, electoral officials, and security forces occurred across the country, often over allegations of vote fraud. In Walungu, in eastern Congo’s South Kivu province, a police officer fired on voters who angrily accused a CENI technician of manipulating the vote for Shadary, seriously injuring a man. The voters seized the officer’s gun and fatally shot him, then beat the technician to death.

The Catholic Church, which had over 40,000 election observers across the country, and the independent Congolese observation mission known as SYMOCEL found widespread irregularities on election day, including polling places in prohibited locations such as police stations or political party headquarters, and limited access for and the expulsion of observers. SYMOCEL reported that 27 percent of the polling places they observed opened late, 18 percent had problems with voting machines, 17 percent allowed voting by people without voting cards or whose names were not on the rolls, and 24 percent closed without allowing those still in line to vote.

The Congolese government, in an apparent attempt to minimize outside scrutiny, had refused all international logistical and financial support to organize the elections. The CENI president repeatedly promised that the elections were on track, including with the new voting machines, and Kabila claimed the elections would be “the best elections this country will have known since 1959.”

On December 28, the government expelled the European Union’s ambassador, Bart Ouvry, with 48-hours’ notice. This followed the EU’s decision on December 10 to renew sanctions against 14 senior Congolese officials, including Shadary.

Over the past four years, the government has systematically sought to silence, repress, and intimidate the political opposition, human rights and pro-democracy activists, journalists, and peaceful protesters. Several prominent opposition leaders were banned from running in the presidential election, and many opposition leaders and supporters and pro-democracy activists remain imprisoned or in exile.

The campaign period included violent crackdowns on rallies of the two main opposition candidates, Martin Fayulu and Félix Tshisekedi, restrictions on Fayulu’s movements, and violent clashes between supporters of different parties. In contrast, Shadary was able to campaign freely with the full support of state officials, use of government resources, and unlimited access to state media.

During the campaign, large-scale ethnic violence broke out in Yumbi, in western Congo’s Mai-Ndombe province, leaving at least 150 dead in a previously peaceful region. Yumbi was among the three areas whose elections were postponed until March, in addition to Butembo and Beni (territory and town) in eastern Congo, which have been affected by a recent Ebola outbreak and attacks by armed groups. The state-controlled CENI’s decision – officially based on security and health concerns – excluded more than 1.2 million voters from participating in the presidential elections. Beni and Butembo residents staged symbolic elections to show that the postponement was unfounded.

On January 3, the Congo’s Catholic bishops conference announced that based on its observations, there was a clear winner in the presidential race, and called upon the CENI to publish accurate results. An African Union observation mission said in a preliminary statement that it strongly wished “that the results that will be declared are true to the vote of the Congolese people.”

Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Congo is a party, states:

Every citizen shall have the right and the opportunity… [t]o vote and to be elected at genuine periodic elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret ballot, guaranteeing the free expression of the will of the electors.

“The African Union and other governments should make clear to Congo’s leadership that any manipulation of the election results will have serious consequences,” Sawyer said. “Rigged or fake vote tallies would only inflame an already tense situation and could have disastrous repercussions.”

Election Day Restrictions, Violence

Interference in Voting

In Mutongo, in North Kivu’s Walikale territory, Congolese army soldiers deployed to polling places tried to force people to vote for Shadary, the ruling coalition presidential candidate. A teacher said:

The FARDC [Congolese army] soldiers who are deployed in the various polling stations of the center forced every voter to vote for Shadary. When I went to vote, they told me, “If you don’t vote for Shadary, we will arrest you.” They even followed me to the polling booth to see whom I would vote for. I voted for Shadary because I was forced to and to protect my life. Shadary is not the candidate of my choice. The results of the vote here in our area will not reflect our will, but the will of the military.

In other parts of Walikale, armed group members intimidated people to vote for Shadary and ruling coalition legislative and provincial candidates. The armed groups included the Kifuafua armed group in the Waloaluanda grouping (groupement), Raia Mutomboki fighters in Walowa-Yungu, and Nduma Defense of Congo-Rénové (NDC-Rénové) fighters in Kisimba, Utunda, and Ihana.

On December 29, NDC-Rénové fighters attacked the village of Kashuga and its surroundings in Masisi territory, an area known to be an opposition stronghold. Many villagers were forced to flee and were unable to vote the following day.

Fighters from the Mapenzi armed group, allied to the NDC-Rénové, were seen in several villages in southwestern Masisi forcing people to vote for Shadary and for two ruling coalition legislative and provincial candidates.

Also in Masisi territory, National Council for Renewal and Democracy (Conseil national pour le renouveau et la démocratie, CNRD) armed group fighters had banned many opposition candidates from campaigning in several localities of the Bashali chiefdom (chefferie), including in the Mweso-Kashuga area. In the areas around Kinyumba, Lwibo, Kilambo, and Lukweti, fighters from the Mapenzi group, in coalition with NDC-Rénové, distributed photos and t-shirts of Shadary and told residents to vote for him.

A farmer in a town in Masisi alleged that a senior member of an armed group arrived at a polling place in a primary school in the town on December 30 at around 1 p.m. with about five fighters, and tried to coerce people to vote for ruling coalition candidates:

When he arrived, he urgently called the head of the voting center, as well as all the heads of the polling stations. First, the vote was suspended. Then, he immediately informed these electoral officials that we have more interest in voting for Shadary, because he is a candidate supported by the president of the republic, Mr. Joseph Kabila, and Congolese in general should vote for him. He went on to tell us that we should also vote for [the ruling coalition candidates in the legislative and provincial elections]. We then started to leave the waiting lines to go home, because we were thinking that we could not vote for a person who was being imposed on us.

In Butare and Mulimbi, in Rutshuru territory, Congolese soldiers also forced people to vote for Shadary and ruling coalition legislative candidates. In the Bwito area of Rutshuru territory though, fighters from the Nyatura armed group faction led by Dominique “Domi” Kamanzi Ndaruhutse, told people to vote for the opposition presidential candidate Fayulu and gave them a list of legislative and provincial candidates. This led some candidates to send gifts to Domi to solicit his support.

Violent Clashes Following Fraud Allegations

Many violent clashes documented across the country on voting day reflected deep suspicions and mistrust in the credibility of the vote and the use of electronic voting machines.

The brother-in-law of Daniel Mugisho Buhendwa, the CENI technician who was killed during the altercation in Lurhala in Walungu, said that Buhendwa was assigned to five polling places:

There was a jammed voting machine in one of the offices, and he started repairing it by bringing in a test ballot. But the voters thought he was submitting a fake ballot for Shadary. The center manager explained to them what Daniel was doing but they wouldn’t listen. The tension was rising, and many other people arrived. They made a lot of noise. People wanted to come in and grab Daniel, shouting that he had voted for Shadary. In response, a policeman fired his gun at the crowd, hitting a man.

People got angrier, and they took the gun away from the policeman and shot him. Meanwhile Daniel, who was trying to escape with the center chief in a jeep, was pulled away and fell to the ground. People rushed toward him with sticks and stones. A stone pushed his left eye in and then his right eye. They beat his head and hit him several times with sticks, and then he died.

Voters beat CENI officials in Kindu and ransacked the CENI office in Inongo, Mai-Ndombe province, following allegations of corruption and fraud. In Kananga, a CENI agent was beaten when he went to a polling place to repair a voting machine. As he was taking the machine away to repair it elsewhere, people beat him, suspecting that he wanted to falsify the results.

In Bandundu, a group of former local members of parliament went to the Jean Bosco parish polling place, allegedly with dollar bills to bribe CENI agents to cheat in their favor. Local youth became angry when the group took the suitcase that had held the voting machine and threw gasoline into the polling place, interrupting the voting. The police restored order and voting later resumed.

A journalist with the Congolese news agency, Agence Congolaise de Presse, said that people reacted in Mbandaka when a CENI agent was found with apparent fake ballots:

I was there myself when voters wanted to beat up the director of a polling station in the Ekofekema Primary School center, after they had caught him with ballots that had been printed [and filled out] in advance. The police later got their hands on him and led him to the police office.

In Mbandaka, in the polling place at the Etinakito school, an election observer said that voters beat up a CENI technician:

The technician who came to repair a broken machine was assaulted by voters who suspected him of wanting to tamper with the machine and the results. He was left with four broken teeth and a battered face. He was saved after the police intervened, and he’s now at the hospital.

Another CENI official was beaten in Boma, Kongo Central province. A witness said:

Voters badly beat the head of a local CENI office when he came to the polling station at the Mardoly school complex in a CENI jeep with another reserve machine to replace the machine that was causing operational problems. Voters believed that the reserve machine was a fake machine to facilitate fraud, so they beat the center chief up and damaged the machine. The CENI agent was saved thanks to the intervention of the police.

In the same center in Boma, a witness said that another voter said that the voting machine printed Shadary’s name, and not the opposition candidate he had voted for:

A voter selected Candidate #4 – Fayulu – but his ballot came out of the machine with #13, Shadary, marked. Upset, the voter took the machine and threw it on the ground. The police intervened and arrested him.

Restricted Access for Independent Observers

Access to polling places for independent election observers was restricted in parts of Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, Rutshuru, Walikale, Lubero, Fizi, Bunyakiri, Kindu, Dimbelenge in Kasai Central, Bakwa Kenge in Kasai, Tshikapa, Mbandaka, and Kungu in Équateur, among other places, observers and media reported. The CENI also failed to issue accreditations for many election observers before the elections, RFI reported.

An election observer from Friends of Nelson Mandela for the Defense of Human Rights (Les Amis de Nelson Mandela pour la défense de Droits Humains, ANMDH) in Kinshasa said that a CENI official ordered the police to refuse him access to a polling place at the Les Anges school complex, in Kingabwa, Limete commune:

In the morning, young people had vandalized voting machines and then burned them, after waiting impatiently for the voters’ lists that were not arriving. Others burned tires on the road. The police intervened to restore order. The lists eventually arrived late, about 5 p.m., and it is at that time that voters had to start searching for their names and enter the polling station. I introduced myself as an observer on behalf of our organization, but the CENI agent there told the police not to let me in: “It is you who are selling the country to those abroad. Since the European Union has not been allowed to work as an observer, it went through you so you would give them information. You are not going to enter here, sir.”

A witness in Kinshasa said that police officers denied observers access to a polling place:

When we arrived at the voting center in the morning, in Masina commune, the polling stations were still closed. When they opened at about 8 a.m., the election officials told us that due to the rain, they would start operations late. It was about 9 a.m. that they posted the voters’ list, and when the observers and witnesses wanted to enter the polling station, the police intervened, claiming that there were already observers and witnesses inside, which was false because they had just opened the office. So, the observers didn’t have access. And the voters who came out said that they had not seen any observers or witnesses in the room.

An observer with a human rights group in Mbandaka said that a polling place official denied him, his colleagues, and other observers access to a polling place in the Liziba center:

While we wanted to enter the polling station to observe how the elections were going, the person in charge of the polling station simply told us: “Here, we don’t need observers.” We insisted, but it was really a categorical refusal. We were therefore unable to observe.

An activist from Mweka, Kasai Occidental said that observers from the Union Fait la Force (UFF) party of the ruling coalition, who supported one candidate for parliament, were chased away by activists from the People’s Party for the Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD), the largest party from the ruling coalition, who supported another candidate. The activist said that the PPRD activists also chased away opposition observers.

In Mbuji Mayi, Kasai Oriental province, alleged members of Governor Alphonse Ngoyi Kasanji’s youth league known as “100 percent” attacked Urbain Kabey Kabey, a journalist, on December 30 at around 10 a.m. Kabey later said:

In the morning I took my camera and went to the polling stations to film the voting process. While I was at Sumaili Lubobo School, the provincial governor arrived with 14 people from his delegation. They entered the polling station and all voted, and I filmed the scene. After that, a truck arrived in the center with new voting machines. Voters began to protest, suspecting something suspicious because the vote had already begun, and they did not understand why these new machines had arrived.

I started interviewing people. That’s when I heard a voice saying, “Pull that camera from him.” I didn’t see the person who said it, but I saw people in civilian clothes assaulting me. They made me fall on the ground and hit me in the hand so that I would let go of the camera. As I still held on to it, one of them hit me in the head with a rock and that’s how I lost my camera. They also took all my phones. This was all in the presence of the police, who did nothing to stop them.

He said that because of the incident, he is in hiding.

Some foreign journalists, including from France 24, Radio France Internationale, and the Belgian francophone Radio Télévision Belge Francophone (RTBF), did not get accreditation to cover the elections.

Voter Suppression

Many voters considered the CENI’s decision to postpone elections in Yumbi in western Congo and in the opposition strongholds of Beni town, Beni territory, and Butembo in eastern Congo to be arbitrary. A Butembo resident who took part in the symbolic election, organized by the democracy group LUCHA (Lutte pour le Changement, or Struggle for Change) and other residents, said: “I went to vote because I had to do my civic duty. I wanted to show the world that the arguments put forward by the CENI are unfounded, and that it was merely a political decision to deprive Fayulu of his electorate.” A Beni resident said: “Markets are functioning, and so are schools, demonstrations, and many other activities. It’s not that Sunday [election day] only that could have aggravated the [Ebola] contamination. This is politics and nothing else.” A nurse member of the Ebola response team, also a Beni resident, who “voted” in the symbolic election, said: “As a member of the response team, we had already discussed how people should behave on election day, and we did not see that there was a risk of the disease spreading.”

Many voters in Kinshasa were also deprived of their right to vote. The CENI said on December 19 that they had already replaced the 8,000 voting machines that were destroyed by alleged arson at one of its warehouses in Kinshasa on December 13, but decided later to close more than 1,000 polling places in Kinshasa for lack of material. This led to confusion about where voters should cast their ballots, delays in the opening of polling places and in posting voter lists, and long waits – shrinking the voting capacity of another opposition stronghold.

In some polling places where the voter lists were posted the day before or the morning of the vote, some voters could not find their names on the lists and eventually left without voting.

One Kinshasa voter said:

I arrived early in the morning in the rain to avoid the crowds, but after more than an hour of searching, I still couldn’t find my name. Other voters tried to help me in vain. I got angry with a CENI agent who wasn’t able to help me. Eventually, soaking wet, I had to go home without voting.

Another Kinshasa voter said that an elderly man struggled to find his name on the voters’ list:

After I voted myself, I found an old man who told me he was born in 1935 and that he couldn’t make his way into the crowd to find his name on the voters’ lists. [I then helped him find his name.] I noticed then that there were no CENI agents assigned to help the elderly or disabled people to vote. If I wasn’t there, this old man probably would have gotten discouraged and gone home without voting.

Delayed openings of polling places and long waits also prevented many people from voting in other parts of the country, including in Boma, Bunia, Gemena, Goma, Kalemie, Kamina, Kananga, Lubumbashi, Maniema, and Mbandaka, observers and media reported.

Violent Crackdown Before Election Day

The CENI’s decision to postpone elections in Yumbi, Beni, and Butembo until after the new president was sworn in prompted protests in Beni, Butembo, and Goma on December 27 and 28. Some of these protests became violent. Government security forces at times responded with excessive and lethal force.

In Beni, protesters tried to enter the CENI office on December 27 to demand a reversal of its decision. Demonstrators ransacked an Ebola transit center, burning some tents and stealing tables and chairs. Twenty-four patients, including 17 who had tested negative for Ebola, fled. Security forces shot live rounds and teargas at protesters, killing one, wounding at least four, and arresting four others, who were released the following day.

On December 28, during a protest by youth in Beu commune in Beni, security forces shot three young people, killing one, and arrested at least four others, who were later released. Protesters looted and burned down a police commander’s home, said a foreign journalist present at the protest.

During protests in Butembo on December 28, police arrested 12 LUCHA activists, 6 members of other activist groups, and 7 members of opposition political parties. A LUCHA activist said: “About 11:30 a.m., they arrested us and accused us of public disorder, insulting the head of state, and trespassing into CENI installations. They interrogated me about who finances LUCHA and what our objectives are.” All 25 people were released the next day, but two of them later went into hiding after they had heard that agents from the ANR, the national intelligence agency, were looking for them.