(Juba) – Both government and opposition forces and their allies committed extraordinary acts of cruelty that amount to war crimes in South Sudan since fighting began there in December 2013, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. In some cases, the actions amounted to potential crimes against humanity.

The 92-page report, “South Sudan’s New War: Abuses by Government and Opposition Forces,” documents how widespread killings of civilians, often based on their ethnicity, and mass destruction and looting of civilian property, have defined the conflict. South Sudan’s government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army-in Opposition forces and their allies should ensure an immediate end to all abuses against civilians, and agree to a justice process that meets international standards for the most serious crimes. The scale and gravity of the abuses warrant a comprehensive arms embargo on South Sudan, as well as targeted sanctions on individuals responsible for serious violations of international law.

“The crimes against civilians in South Sudan over the past months, including ethnic killings, will resonate for decades,” said Daniel Bekele, Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “It is essential for both sides to end the cycle of violence against civilians immediately, and to acknowledge and support the need for justice.”

South Sudan’s war began in Juba, the capital, triggered by a political dispute between President Salva Kiir, from the Dinka ethnicity, and former Vice President Riek Machar, from the Nuer ethnicity. The fighting quickly spread across large swathes of the eastern part of the country.

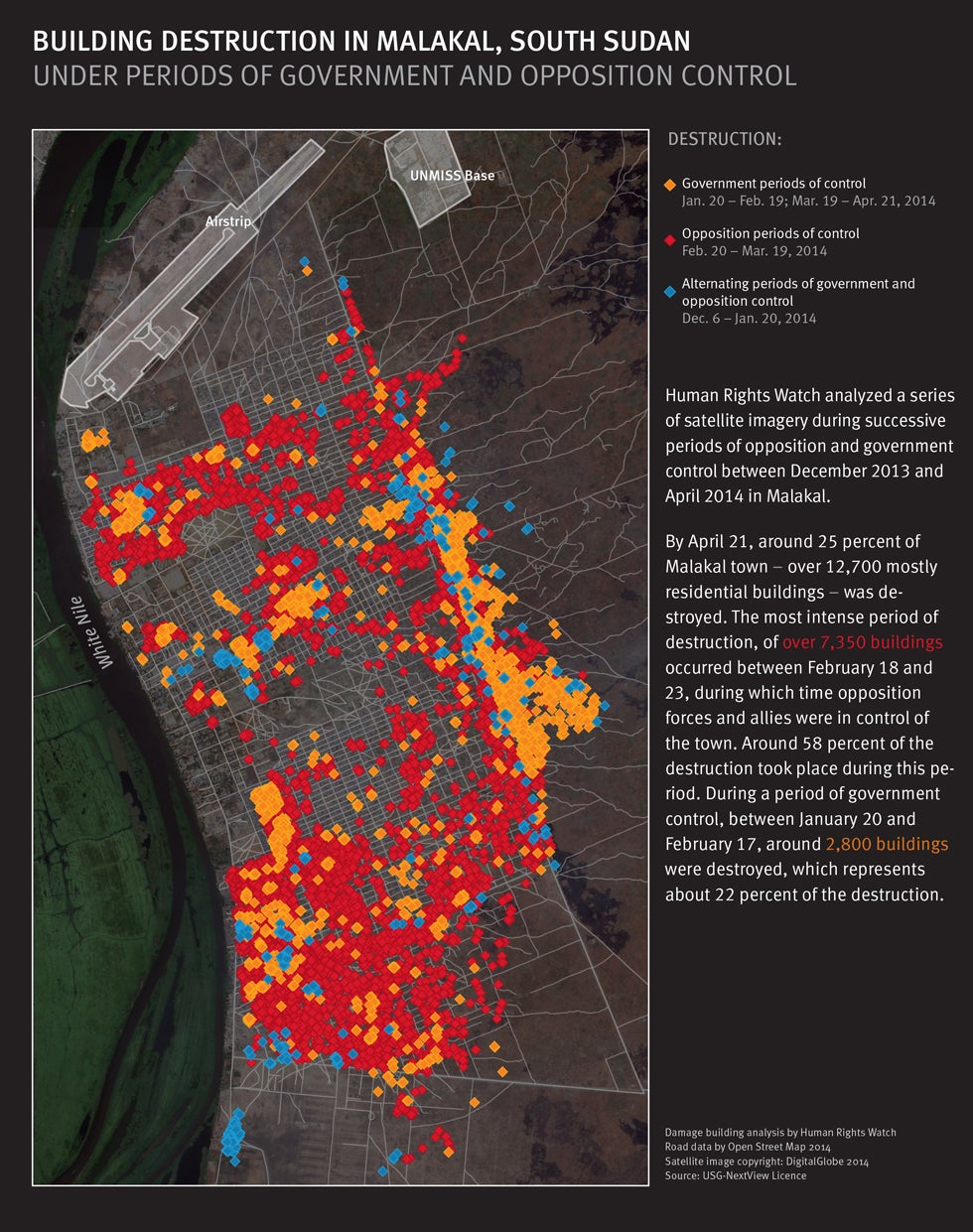

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 400 survivors and witnesses and documented numerous attacks on ethnic Nuer civilians in Juba during the early days of the conflict, including a massacre, unlawful killings, round-ups, detentions, and torture. After the violence spread with thousands of Nuer joining opposition forces and targeting ethnic Dinka, Human Rights Watch documented hundreds of killings of civilians by both sides in the towns of Bor, Bentiu, and Malakal. These were main sites of the conflict in its first months and changed hands multiple times. Both government and opposition forces have been responsible for widespread pillage and destruction of civilian property such as homes, markets, and aid infrastructure.

“The violence in towns like Bentiu, Bor, and Malakal has been less fighting between the forces than targeted killings of civilians who could not flee, and massive looting and destruction,” Bekele said. “The attacks have left destroyed, largely deserted towns dotted with the bodies of women, children, and men, and have resulted in mass displacement and hunger.”

The conflict and abuses have driven an estimated 1.5 million people from their homes. Over a million have been displaced within South Sudan, including 100,000 who have taken refuge in United Nations peacekeeping bases where they are living in poor conditions. More than 400,000 have fled to neighboring countries such as Ethiopia and Uganda. An unknown number have been forced to places where they have little access to food and other supplies. Aid workers and food security researchers have predicted that communities in some conflict-affected areas of South Sudan may soon experience famine.

The UN Security Council, which is visiting South Sudan and neighboring countries this week, should promptly impose an arms embargo on the country and targeted sanctions against individuals responsible for grave abuses, Human Rights Watch said. South Sudan has purchased large quantities of weapons since the conflict began, including from China, presumably for use in the fighting.

South Sudan’s leaders, currently in negotiations in Addis Ababa, should agree that there will be no amnesty for serious crimes and immediately make a commitment to a credible justice process. Long-standing impunity for abuses committed in South Sudan has fueled recent crimes. Fair, effective prosecutions can help to pave the way for greater respect for the rule of law and a durable peace over the longer-term, Human Rights Watch said.

The government has yet to make public the findings of several investigations into the killings or prosecute those responsible. Opposition forces have also not held their abusive forces to account, as far as Human Rights Watch could ascertain. Domestic prosecutions are unlikely to succeed, given South Sudan’s lack of political will to hold abusive forces to account, and weaknesses in South Sudan’s judicial system, Human Rights Watch said.

Among the options leaders could consider are a hybrid international-national judicial mechanism with relevant international support and participation – such as international investigators, prosecutors, and judges. Investigation by the International Criminal Court (ICC) could also be pursued. As South Sudan is not a member of the ICC, this could only come about through a request by South Sudan’s government or a UN Security Council referral of the situation in South Sudan to the ICC.

Thorough, ongoing reporting on human rights violations and crimes by both sides is a crucial first step toward any justice process, Human Rights Watch said. The African Union’s (AU) Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan, initiated soon after the conflict began, has been slow to begin investigating human rights violations. The commission should focus on investigating individuals allegedly responsible for war crimes and potential crimes against humanity during the conflict and should collect forensic and other evidence of crimes, including at alleged mass graves in Juba and elsewhere, Human Rights Watch said.

Human rights officers for the UN mission in South Sudan should continue to investigate and regularly publicly report on crimes by both sides, including the abuses that have contributed to the conditions for famine, and collaborate with the AU inquiry in its work.

“The brutality seen in this conflict is a result of decades of abuse without justice for the loss of life and property,” Bekele said. “The world can and should help South Sudan to stop the current crimes as well as the longstanding cycle of violence fueled by impunity.”