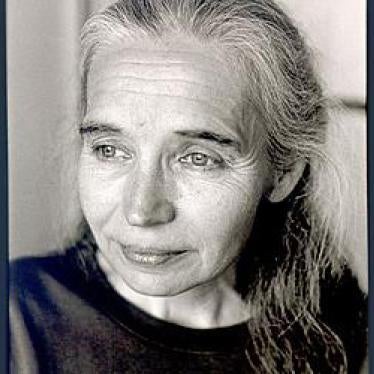

When Voice of America journalist Samuel Tiendrebeogo called me this past Friday the 13th to inform me of Alison's tragic death, I was grief-stricken. How could God have allowed such a monstrous injustice? Alison gave, helped, and loved so much that she could only have died peacefully in her sleep at a hundred years old-she was tireless. That's how I imagined Alison leaving this life. At moments like these my faith is shaken and my dialogue with God becomes an quarrel, a rebellion. They say the Lord works in mysterious ways, and in this case it's true: I cannot understand how God showed His love, and He couldn't not love Alison des Forges.

I wrote nothing right away, because I knew I wouldn't be able to keep control. My head was crowded with so many memories, and it took me a while. I was filled with anger, too. There will always remain an unfinished chapter between Alison and me. We promised each other we'd do so many things when we became little old ladies, just rambling on and getting our memories muddled. And we did have our memories, Alison and me! Some five years of sharing and partnership, of dreams and rebelliousness, of tears and rage and fighting. Alison wasn't my colleague. She was my sister, as strange as that may seem, and we were connected more deeply than in the usual sense. Together, Alison and I lived twenty lives, each one a hundred years long.

Where I come from they say memories are firewood for warming our old age. She's left me well stocked, my sister Alison. I'll tell you one story: in November 1991 she arrived in Kigali together with a young African-American intern. We had to go to Murambi in the Mutara region to investigate killings there that the media hadn't been covering. She rented a little yellow car, and when she came by to pick me up at my office I told her " Alison, your car is too conspicuous for a trip as risky as this" She said, "I got it because I figured you'd like the color."

Not only did I like the color-it made it easier for all our friends who were following us for our protection, or to monitor what we were doing, because the car was so easily recognizable. Along the route of our investigation we had to pick up two injured persons and take them to the hospital, but the car was too small. So I suggested I ride in the trunk to make room for one of them. Alison refused, saying "Monique, you can't be serious-a car with a white driver and a black woman in the trunk? You want to get me killed, or what?" We really laughed. I told her I'd stick up for her if she got arrested, and everything would be fine-as long as she didn't tie me up before putting me in the trunk!"

Alison told me, "I wouldn't go that far. But, hey-Monique, aren't you too fat for the trunk? It's a perfect fit for me." I told her that if I were a Western woman she'd be in deep trouble for that remark but, in Africa, they like my curves! She got into the trunk with me at the wheel, and we drove like that along the 70 kilometers of mud road leading to the hospital. When I wondered if she'd be all right that way she told me it was a good way to learn to dance and that, by the time she got out, she'd really have the rhythm in her bones, and we laughed. We laughed to lighten things up, in order not to cry. We laughed to get through so much of the suffering and injustice we experienced together. On that investigation we brought back a human skull that had been split open by a machete, for evidence.

We were detained at one roadblock by a soldier who wanted to search the vehicle. We were panicked. Another soldier was grilling the young African-American, and he was getting offended because the young girl couldn't answer his questions. The two solders were shouting themselves into a lather. The one trying to question the girl thought he was being snubbed, but in fact the poor thing couldn't understand the soldiers Kinyarwandan dialect! Try explaining to a stressed-out soldier that there are blacks who don't speak Kinyarwandan! He was convinced she was my sister because of our skin color and a slight similarity in our features.

We were in a bad fix. We had to find a quick and effective way to get out of that situation right away. So, since I knew the commanding officers of all the garrisons in the country at that time, I told the highest-ranking soldier in the group that were expected by the commanding officer who was expecting the young girl in the car, and that they would be held responsible for our delay. He immediately gave the order to let us go. Alison said to me, "Monique, you're a witch. What did you whisper in that soldier's ear?" I told her that, in a pinch, knowing a leader's weaknesses can be a major asset-especially in troubled times. We couldn't stop laughing.

During the period of time when we were unable to speak with one another, when I was in hiding in the attic of my house, the massacres were raging outside, and Alison gave me sound guidance. She told me I would survive, in spite of the horror going on all around me, and I began to believe it as well. That's what saved me. When I told her I wasn't going to be able to make it, and she would have to take care of my children, she forbade me to think of dying. She told me that she and I knew I just couldn't die, that there was too much to do-as if it were up to us! But she was right. I'm still here.

What can I say about the succession of visits to all the big offices in the United States, after I got out of the hell that was Rwanda in April of 1994? Alison kept me from drowning in my grief, even when I didn't know where my children were. With her I could laugh again; she knew how to reach me with a joke. She sensed when I was falling apart, and she was always there at the right time with something to say, to keep me from getting carried away in my grief. I owe her much. Life kept us apart from one another, somewhat, and the nature of my struggles has changed, but whenever we talked it was a sheer delight.

Alison shouldn't have died like this, but it is over and we can do nothing about it. Alison is gone, physically, but she will live inside of us forever. I have to maintain my faith, because it is the only way I can keep the hope of seeing her again someday. Alison, you were a Great Lady, with a big heart and a noble soul. I was lucky to share intense moments in my life with you.

* Dr. Monique Mujawamariya was a prominent human rights activist in Rwanda at the time of the Rwandan genocide in 1994. With the help of Alison Des Forges, she managed to escape death. Dr. Mujawamariya currently lives in Montreal, where she is founder and president of the organization Mobilisation Enfants du Monde (MEM).