Vietnam continued to systematically violate basic civil and political rights in 2020. The government, under the one-party rule of the Communist Party of Vietnam, tightened restrictions on freedom of expression, association, peaceful assembly, movement, and religion. Prohibitions remained on the formation or operation of independent unions and any other organizations or groups considered to be a threat to the Communist Party’s monopoly of power. Authorities blocked access to several websites and social media pages and pressured social media and telecommunications companies to remove or restrict content critical of the government or the ruling party.

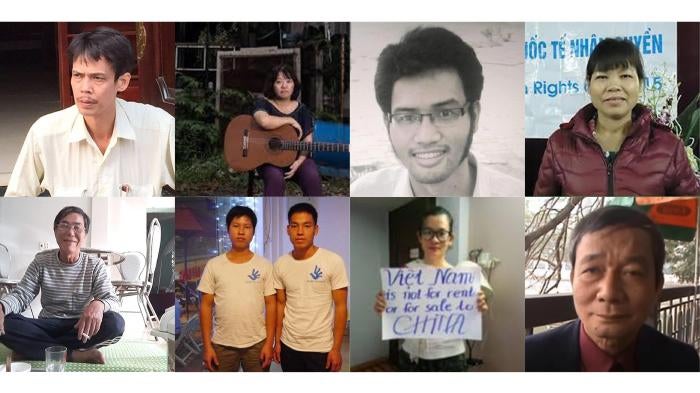

Those who criticized the government or party faced police intimidation, harassment, restricted movement, physical assault, arbitrary arrest and detention, and imprisonment. Police detained political detainees for months without access to legal counsel and subjected them to abusive interrogations. Party-controlled courts sentenced bloggers and activists on fabricated national security charges.

Vietnamese authorities appeared to have had some successes in combating the Covid-19 pandemic. After adopting aggressive contact tracing, mass testing, public campaigns on hygiene, early border closures, social-distancing, and mandatory centralized quarantines, Vietnam by late 2020 reported only about 1,000 confirmed cases and 35 deaths. However, Vietnam’s successes came at the cost of increasing violations of rights: restrictions on freedom of speech; failure to protect the right of privacy; and inequity in access to social services and government support.

Freedom of Expression, Opinion, and Speech

Online dissidents faced routine harassment and intimidation in 2020. Several were arrested and charged under Vietnam’s penal code, which criminalizes speech critical of the government or which promotes “reactionary” ideas. The government prosecuted numerous dissidents throughout the year.

In April, June, and July, courts tried Phan Cong Hai, Nguyen Van Nghiem, Dinh Van Phu, and Nguyen Quoc Duc Vuong and sentenced them to between five and eight years each in prison for criticizing the party and the state.

Police arrested Nguyen Tuong Thuy in May and Le Huu Minh Tuan in June for involvement with the Independent Journalists Association of Vietnam (IJAVN) and charged them with anti-state propaganda under article 117 of the penal code. The organization’s president, Dr. Pham Chi Dung, was arrested in November 2019, apparently in connection to his vocal opposition to the European Union-Vietnam free trade agreement. Between April and August, police arrested nine other people including independent blogger Pham Chi Thanh, land rights activists Nguyen Thi Tam, and former political prisoner Can Thi Theu and her sons Trinh Ba Phuong and Trinh Ba Tu. In October, police arrested prominent rights blogger Pham Doan Trang. All 10 were charged with anti-state propaganda under article 117 of the penal code.

Freedom of Media and Access to Information

The Vietnamese government continued to prohibit independent or privately owned media outlets and impose strict control over radio and television stations and printed publications. Authorities block access to websites, frequently shut blogs, and require internet service providers to remove content or social media accounts deemed politically unacceptable.

In April, the government throttled access to Facebook’s local cache servers, demanding that the company remove pages controlled by dissidents. Facebook, bowing to pressure, agreed to restrict access to the pages within Vietnam, setting a worrying precedent. In early September, the Ministry of Information and Communications (MIC) praised Facebook and YouTube for their “positive change in collaborating with MIC to block information that violates Vietnam’s law.”

In April and May, a court sentenced two Facebook users, Chung Hoang Chuong and Ma Phung Ngoc Phu, to 18 months and 9 months’ imprisonment respectively for posts on Facebook critical of the government under article 331 of the penal code. In June, authorities arrested Huynh Anh Khoa and Nguyen Dang Thuong for being the moderators of a Facebook group in which users discussed Vietnamese economic, social, and political issues, and charged them also under article 331.

Freedom of Association and Assembly

Prohibitions remained on independent labor unions, human rights organizations, and political parties. Organizers trying to establish unions or workers’ groups face harassment, intimidation, and retaliation from employers and authorities. Authorities require approval for public gatherings, and systematically refuse permission for meetings, marches, or public gatherings they deem to be politically unacceptable.

In November 2019, the National Assembly passed a revised labor code effective in January 2021. The new code ostensibly will allow the formation of “Worker Representation Organizations” to represent workers, but such groups can only form with the permission of the government and are likely to be tightly controlled.

In April, the police arrested former political prisoner Tran Duc Thach for alleged association with a human rights group, the Brotherhood for Democracy. Authorities charged him with subversion under article 109 of the penal code.

As in previous years, the government confiscated land for various economic projects, typically without due process or adequate compensation. The term “dan oan,” or “wronged people,” as of 2020 has emerged as a common idiom in Vietnamese usage to describe people forced off their land by authorities.

In January, a violent incident occurred in Dong Tam, a commune in Hanoi, involving police and land rights activists involved in past protests against local land confiscations in the area. Details are unclear, but several deaths were reported, including three police officers and one villager. Authorities arrested 29 villagers and charged them with murder or resisting persons on public duty. In September, a court in Hanoi convicted and sentenced two of them to death. Another was sentenced to life in prison. The rest received either suspended sentences or various shorter terms, ranging up to 16 years. Defense lawyers said several defendants alleged they were tortured and forced to admit guilt.

Freedom of Religion

The government restricts religious practice through legislation, registration requirements, and surveillance. Religious groups are required to get approval from, and register with, the government and operate under government-controlled management boards. While authorities allow many government-affiliated churches and pagodas to hold worship services, they ban religious activities that they arbitrarily deem to be contrary to the “national interest,” “public order,” or “national unity,” including many ordinary types of religious functions.

Police monitor, harass, and sometimes violently crack down on religious groups operating outside government-controlled institutions. Unrecognized religious groups, including Cao Dai, Hoa Hao, Christian, and Buddhist groups, face constant surveillance, harassment, and intimidation. Followers of independent religious group are subject to public criticism, forced renunciation of faith, detention, interrogation, torture, and imprisonment.

Children’s Rights

Violence against children, including sexual abuse, is pervasive in Vietnam, including in schools. Numerous media reports have described cases of teachers or government caregivers engaging in sexual abuse, beating children, or hitting them with sticks.

Vietnamese lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth face widespread discrimination and violence at home and at school. Pervasive myths about sexual orientation and gender identity, including the false belief that same-sex attraction is a diagnosable and curable mental health condition, is common among Vietnamese school officials and the population at large.

Schools often fail to protect students from physical violence and school staff inconsistently respond to incidents of verbal and physical abuse and lessons often contain homophobic content. Authorities have not put in place adequate mechanisms to address cases of violence and discrimination.

Key International Actors

China remains the most influential outside actor in Vietnam. Maritime disputes continue to complicate the relationship.

In February, the EU and Vietnam held their ninth yearly human rights dialogue, an exercise that once again did not bring concrete results. In August, the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement came into force, strengthening Vietnam’s ties with the bloc. The deal includes vague, non-enforceable human rights provisions. Amid increasing repression of any form of dissent in the country, EU pressure focused solely on labor rights, triggering some reforms and commitments by Hanoi. Despite acknowledging major concerns over Vietnam’s deteriorating human rights record, in February a majority in the European Parliament gave its consent to the deal.

2020 marked the 25th anniversary of the resumption of diplomatic relations between the United States and Vietnam. While the current US administration paid little attention to human rights situation in Vietnam, a number of US politicians continued to condemn the country’s violations of rights and voice their supports for Vietnamese activists.

In April 2020, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom published its report in which Vietnam is recommended for designation as a “Country of Particular Concern.” In October 2020, the US and Vietnam held a human rights dialogue, virtually, during which US officials claim to have raised concerns about various human rights issues. However, the arrest of prominent dissident Pham Doan Trang, noted above, occurred less than 24 hours after the end of the dialogue, underscoring its lack of efficacy.

Australia’s bilateral relationship with Vietnam continued to grow even as an Australian citizen, Chau Van Kham, remained in prison in Vietnam on a “terrorism” conviction for his alleged involvement in an overseas political party declared unlawful by the Vietnamese government.

Japan remained the most important bilateral donor to Vietnam. As in previous years, Japan has declined to use its economic leverage to publicly urge Vietnam to improve its human rights record.