The human rights, security, and humanitarian situation in Burkina Faso was precarious amid ongoing violence and atrocities by Islamist armed groups, state security forces, and pro-government militias engaged in counterterrorism operations.

In 2020, the Burkinabé security forces allegedly executed hundreds of suspects, last seen in their custody, for their perceived support of Islamist groups. Armed Islamists allied to Al-Qaeda and the Islamist State in the Greater Sahara attacked civilians and summarily executed people, causing the death of over 160 people. Armed group attacks caused 450,000 people to flee their homes in 2020 alone, bringing the total number of internally displaced since the conflict started in 2016 to over one million.

A 2019 law criminalizing some aspects of reporting on security force operations had a chilling effect on freedom of the press and on journalists and human rights defenders, some of whom received threats after reporting on security forces abuses.

While the government opened several investigations into reported abuses, little progress was made toward providing justice for victims, including of large-scale atrocities by all sides. Rule-of-law institutions remained weak and hundreds of terrorism suspects remained in custody without trial, in part because of the lack of defense lawyers.

Burkina Faso’s international partners including the United Nations, France, the European Union and the United States readily denounced violence by armed Islamist groups but were largely reluctant to denounce abuses by government forces.

Abuses by Islamist Armed Groups

Islamist armed groups attacked churches, mosques, aid convoys and schools. They sought to justify their attacks by linking victims to the government and allied militias, the West, or Christianity. Their attacks, including several massacres, largely targeted members of the Mossi and Foulse ethnic groups.

A December 24, 2019 attack in Arbinda killed at least 35 civilians, mostly women previously displaced by the violence. Attacks on Rofénèga, Nagraogo, and Silgadji villages between January 17 and 25 left over 90 civilians dead. On February 1, at least 20 civilians, including a nurse, were killed in Lamdamol village, and a February 16 attack on a church in Pansi village killed over 20 civilians, including the pastor.

In May 2020, Islamist armed groups were implicated in an attack on a convoy of traders in Lourom Province that killed at least four women, and another on a convoy transporting food aid near Barsalogho that killed five civilians. Both convoys were escorted by government troops, some of whom also died.

Islamist armed group attacks on villages have put women and girls at increased risk of physical and sexual violence.

Armed Islamists abducted several local government officials and prominent elders, later killing some of them. The village chief of Nassoumbou was abducted in July and released in September, and in August, the 73-year-old Grand Imam of Djibo, Sonibou Cisse, was executed several days after being taken off a public transport vehicle south of Djibo.

Numerous civilians, including children, were killed by improvised explosive devices (IEDs) believed to have been planted on roadways by armed Islamists, including 14 civilians, at least two of them children, in January, when their bus hit an explosive device in Boucle du Mouhoun region, and six shepherds, all children, in Tangaye village in August.

Islamist armed groups also imposed their version of Sharia (Islamic law) via courts that did not adhere to international fair trial standards.

Abuses by State Security Forces

Burkinabé security forces from the army and gendarmerie unlawfully executed suspects during counterterrorism operations in both Burkina Faso and Mali, during cross-border operations. Most of the victims were from the Peuhl ethnic group and were rounded up by security forces in marketplaces and taken from villages, watering holes, or off public transport vehicles.

The remains of 180 men were found around the northern town of Djibo between November 2019 and June 2020. The bodies were found in groups of up to 20 along major roadways, under bridges, and in fields and vacant lots, and the majority were buried in common graves. Many were found blindfolded and with bound hands.

In early March, security forces in Cisse village executed 23 people. On April 9, security forces executed 31 detainees just hours after being arrested, unarmed, during a counterterrorism operation in Djibo. On May 11, 12 men arrested by gendarmes in Tanwalbougou, Est Region, were found dead in their cells hours later. Witnesses said the men appeared to have been shot. According to the United Nations, Burkinabé forces were implicated in at least 50 extrajudicial killings committed during cross-border operations into Mali between May 26 and 28.

Some allegations involved security forces and civil defense forces working together, including on February 29 when at least 15 people were reportedly killed during a joint operation around Kelbo.

On May 2, security force members burst into the Mentao refugee camp, allegedly looking for armed Islamists, and physically abused over 30 Malian refugees.

Attacks by Self-Defense Groups

On January 21, the National Assembly passed a law institutionalizing government support for and training of self-defense groups, known as Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDH). The law’s provisions on accountability are ambiguous. Some members of the Koglweogo, an anti-crime force largely composed of ethnic Mossi, and which has for years been implicated in serious abuses, including the 2019 Yirgou massacre of over 40 men, were subsumed into the VDH.

Self-defense groups were implicated in numerous grave crimes including the killing in February of 19 men taken off a public transport bus near Manja Hien village, attacks on three villages in Yatenga province on March 8 that killed 43 Peuhl villagers, and numerous other killings in villages in northern and eastern Burkina Faso.

Accountability for Abuses

Authorities opened investigations into several allegations involving the security forces and civil defense forces, including the May deaths of 12 men in gendarme custody in Tanwalbougou and the deaths of over 200 men in Djibo. However, there was no progress in the investigations opened into abuses in 2018 and 2019, and there was scant public information about the status of investigations. No charges were brought against armed Islamists.

The military justice directorate, mandated to investigate incidents involving the security forces, was seriously under resourced.

The high-security prison for terrorism-related offenses is overcrowded, mirroring the overcrowding in prisons nationwide. Hundreds of detainees accused of terrorism-related offenses have been held without trial, some for up to four years. Few had access to lawyers. In April, over 1,200 detainees were pardoned and released in a bid to decongest the prisons to slow the spread of Covid-19.

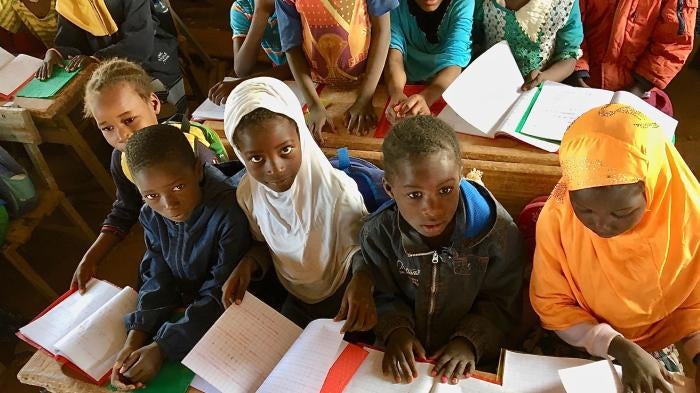

Access to Education and Attacks on Teachers, Students, and Schools

Islamist armed groups carried out over 45 attacks on education in 2020. In 21 documented attacks between January and March, armed men killed, abducted, beat, robbed, and threatened education professionals; intimidated students and parents; and burned and looted 15 schools. From April to August, at least 25 schools were burned, according to news reports. Most of these attacks took place in Est, Nord, and Boucle du Mouhoun regions. The Burkinabé military used at least three schools as bases.

Before the government closed all schools nationwide in response to the Covid-19 pandemic in March, 2,500 schools had already closed due to attacks or insecurity— depriving nearly 350,000 students of education—and schools hosting displaced students suffered from overcrowding, unable to accept all who sought to enroll.

The government responded to attacks by relocating teachers, increasing security patrols near some schools, reopening closed schools, and implementing programs to help students catch up or regain access to school. As part of its Covid-19 education response, the government expanded distance-learning programs to national radio, television, and online platforms.

Key International Actors

The rapidly deteriorating security, humanitarian and human rights situation garnered significant attention from Burkina Faso’s key international partners. They issued several statements denouncing abuses by Islamist armed groups, but for much of the year did not publicly denounce the security forces for serious abuses or publicly press the national authorities to investigate the allegations.

In December 2019, the European Parliament urged the Burkinabé government to end its abusive counter-insurgency strategy and investigate abuses committed by security forces. Following the July 2020 allegations of mass atrocities by security forces in Djibo, the United States said the killings could put US military aid at risk and the European Union and the United Kingdom urged Burkina Faso authorities to investigate the abuses.

The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights committed to strengthening its presence in Burkina Faso.

In June, France launched the International Coalition for the Sahel, to coordinate among the G5 Sahel countries (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger) and their international partners.

The United States trained more than 3,000 Burkinabé soldiers and gendarmes in 2020, and provided US$2 million in counter-IED training programs, as well as $5 million in anti-terrorism funding to develop the investigative capacities of law enforcement to handle complicated terrorism cases.

The European Union has mobilized €4.5 billion in budget support for the G5 Sahel joint counterterrorism force.

France provides military training to Burkinabé troops and supported security operations in the Sahel region through its 5,100-strong Operation Barkhane counterinsurgency operation.

In June, in response to the gravity and number of attacks on schools and the killing and maiming of children, the UN secretary-general added Burkina Faso as a situation of concern for the UN's monitoring and reporting mechanism on grave violations against children during armed conflict.