Ugandan soldiers have tortured and unlawfully killed civilians during law enforcement operations in the Karamoja region, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. The government’s efforts to redress and prevent these abuses are promising but insufficient.

The pastoralist communities of Uganda’s remote, semi-arid Karamoja region struggle against poverty, frequent drought and banditry. Armed cattle raids, carried out by Karamojong, are common and claim countless lives each year. In May 2006, the Ugandan army launched a “cordon and search” disarmament campaign in an effort to bring law and order to the region.

“The Ugandan government has every right to get guns out of the hands of ordinary citizens,” said Elizabeth Evenson, a researcher for the report and Leonard H Sandler Fellow in Human Rights Watch’s Africa division, “but its soldiers must still obey the law.”

The 97-page report, “Get the Gun!: Human Rights Violations by Uganda’s National Army in Law Enforcement Operations in Karamoja Region,” is based on some 50 eyewitness accounts of law enforcement operations carried out by the Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces (UPDF) between September 2006 and January 2007, and on visits to the sites of six of these operations.

Eyewitnesses described incidents to Human Rights Watch in which soldiers fired on children, killing three; used armored personnel carriers to crush two homesteads; and, on several occasions, severely beat and arbitrarily detained men in military facilities to force them to reveal the location of weapons.

Dozens of soldiers were also killed by Karamojong during armed confrontations or ambushes in this same period.

In cordon and search operations, soldiers typically surround homesteads in the middle of the night, and at daybreak force residents outside while their houses are searched for weapons.

In October 2006, the UPDF imposed stricter controls on its soldiers following one particularly violent incident in which an unknown number of soldiers and at least 48 civilians were killed – six of them allegedly by summary execution.

In recent months, cordon and search operations have been markedly less violent and accompanied by far fewer allegations of abuses. A new report by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights also found a reduction in reported human rights violations during the period April to August 2007, as well as a reduction in banditry due to increased UPDF law enforcement efforts.

However, the UN High Commissioner’s report also found that human rights violations continue, including unlawful killings, beatings and arbitrary detentions.

Human Rights Watch remains concerned that very few soldiers have been brought to justice for serious human rights abuses committed during disarmament operations. In spite of improved accountability efforts by the Ugandan army, Human Rights Watch called on the government to provide a more systematic response to human rights violations.

In a September 2007 response to a Human Rights Watch letter setting out key findings of its report, the Ugandan Ministry of Defence/UPDF spokesperson’s office denied that four of the military operations described in the report ever took place. The government response is included in full in the report.

“It’s good that the Ugandan army is trying to control its soldiers during disarmament operations, but abuses are still taking place,” said Evenson. “If these abuses continue to go unacknowledged and unpunished, future abuses are inevitable.”

The Ugandan government will host the biennial Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Kampala on November 23-25, 2007.

“As host of the Commonwealth summit, Uganda should demonstrate its commitment to the Commonwealth values of human rights and the rule of law by ensuring its soldiers respect human rights during operations in Karamoja,” said Evenson.

Eyewitness testimony from the report

This man was detained in a military facility for two weeks and beaten severely while interrogated about the whereabouts of guns:

“The soldiers asked, ‘Why are you here?’ We said, ‘We don’t know why we are here.’ Then they said, ‘You are here because we want the gun.’ … If you say, ‘I don’t know about the gun,’ the soldiers get the stick and begin beating you …. They say, ‘Get the gun! Get the gun!’”

This man was also detained in a military facility. He was detained in a well:

“I was thirsty. [The soldiers] would not give me anything to drink. … We were naked in there even in the damp of the night. We were kept in the well from morning to morning.”

These two children were shot as they fled a cordon and search operation in their village:

“We came out of the village with our parents. I was following my mother and father, and I got shot. My mother was shot in front of me and fell down. Then I was shot. … One bullet went through [my] fingers.”

“I heard the army vehicles and just ran out. I was trying to run, but I saw that the soldiers were already there surrounding the [homestead]. I didn’t even know I was shot until I lay down and saw the blood.”

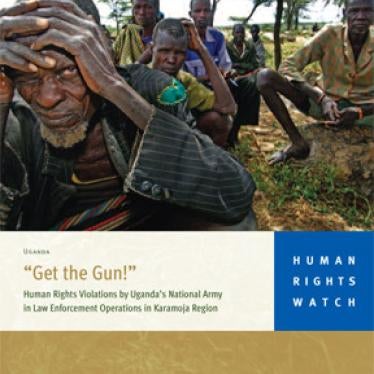

This elderly man was lame and unable to leave his house when soldiers entered to conduct a cordon and search operation and beat him:

“When I remained, the soldiers came inside the village. There was one soldier who pointed his gun at me and wanted to shoot me, but the commander stopped him. Another group [of soldiers] came and said, ‘Why are you here?’ I said, ‘I am lame.’ These two soldiers started beating me. The soldiers knocked me with the barrel of the gun on the head. Then they got out a bayonet and started stabbing me. They stabbed me three times with the bayonet on the head. I was also beaten with a stick on the leg. Just young men were beating me. The [commander] had already said that I didn’t have a gun. I was even kicked in the mouth. I started bleeding. I’m still having pus from my nose.”

This woman explained to Human Rights Watch her frustration with the methods used by soldiers during cordon and search operations:

“If the soldiers wanted to come and search, that would be OK if it was done in a gentle way and the commander came inside [the manyatta, a traditional homestead]. But now the commander stays outside and it is only the young boys who come in. Then they deny to the commanders that [misconduct] has taken place.”