Throughout 2018, government officials and security forces carried out widespread repression and serious human rights violations against political opposition leaders and supporters, pro-democracy and human rights activists, journalists, and peaceful protesters. The December 30 elections were marred by widespread irregularities, voter suppression, and violence. More than a million Congolese were unable to vote when voting was postponed until March 2019 in three pro-opposition areas.

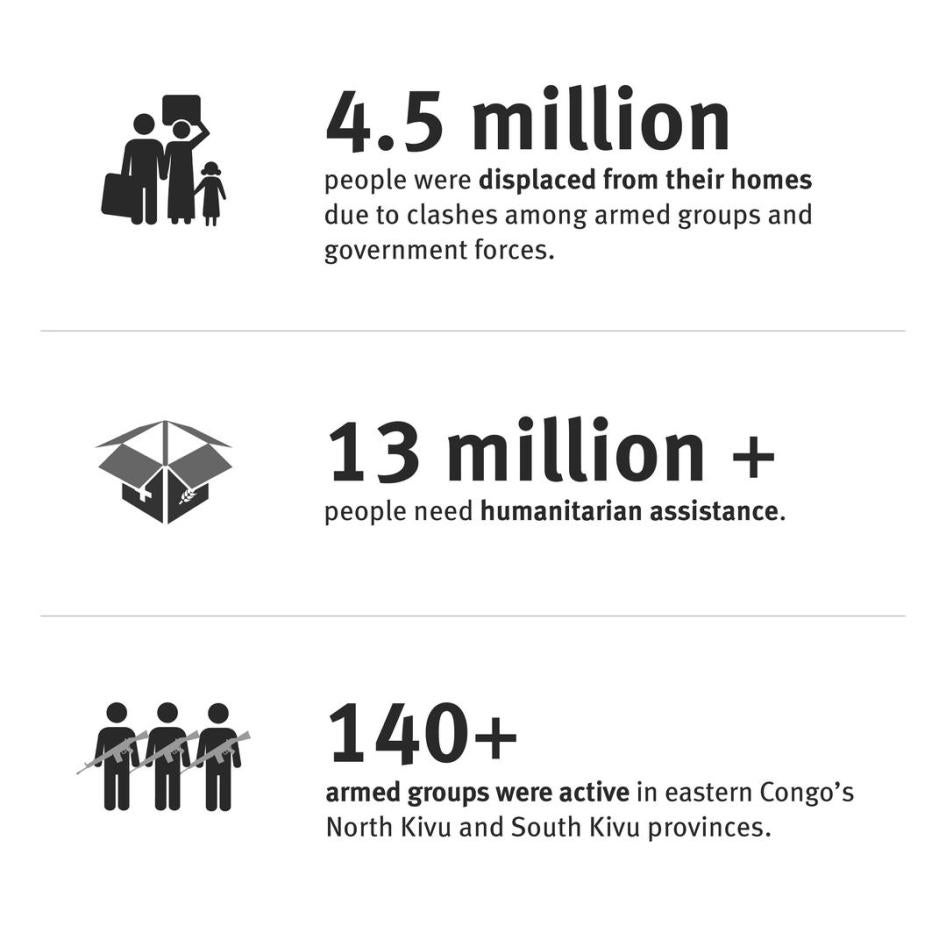

In central and eastern Congo, numerous armed groups, and in some cases government security forces, attacked civilians, killing and wounding many. Much of the violence appeared linked to the country’s broader political crisis. The humanitarian situation remained alarming, with 4.5 million people displaced from their homes, and more than 130,000 refugees who fled to neighboring countries. In April, government officials denied any humanitarian crisis and refused to attend an international donor conference to raise US$1.7 billion for emergency assistance to over 13 million people in need in Congo.

Freedom of Expression and Peaceful Assembly

Throughout 2018, government officials and security forces banned peaceful demonstrations; used teargas and in some cases live ammunition to disperse protesters; restricted the movement of opposition leaders; and arbitrarily detained hundreds of pro-democracy and human rights activists, opposition supporters, journalists, peaceful protesters, and others, most of whom were eventually released.

During three separate protests led by the Lay Coordination Committee (CLC) of the Catholic Church in December 2017, and January and February 2018, security forces used excessive force, including teargas and live ammunition, against peaceful protesters within and around Catholic churches in the capital, Kinshasa, and other cities. Security forces killed at least 18 people, including prominent pro-democracy activist Rossy Mukendi. More than 80 people were injured, including many with gunshot wounds.

Catholic Church lay leaders had called for peaceful marches to press Congo’s leaders to respect the church-mediated “New Year’s Eve agreement” signed in late 2016. The agreement called for presidential elections by the end of 2017 and confidence-building measures, including releasing political prisoners, to ease political tensions. These commitments were largely ignored, however, as President Joseph Kabila held on to power through repression and violence.

On April 25, security forces brutally repressed a protest led by the citizens’ movement Lutte pour le Changement (Struggle for Change, LUCHA) in Beni, in eastern Congo, arresting 42 people and injuring four others. On May 1, security forces arrested 27 activists during a LUCHA protest in Goma, in eastern Congo. Leading democracy activist Luc Nkulula died under suspicious circumstances during a fire in his house in Goma on June 9. Fellow activists and others believe he was the victim of a targeted attack.

In July, two journalists and two human rights activists were threatened and went into hiding following the release of a documentary about mass evictions from land claimed by the presidential family in eastern Congo.

In early August, Congolese security forces fired teargas and live ammunition to disperse political opposition supporters, killing at least two people—including a child—and injuring at least seven others with gunshot wounds, during the candidate registration period for presidential elections. Authorities also restricted the movement of opposition leaders, arrested dozens of opposition supporters, and prevented one presidential aspirant, Moïse Katumbi, from entering the country to file his candidacy.

Congolese police arbitrarily arrested nearly 90 pro-democracy activists and injured more than 20 others during peaceful protests on September 3. The protesters had called on the national electoral commission to clean up the voter rolls after an audit by the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) found that over 16 percent of those on the lists had been registered without fingerprints, raising concerns about potentially fictitious voters. They also called on the commission to abandon the use of controversial voting machines that were untested in Congo and could potentially be used to tamper with results.

A Congolese court sentenced four members of the Filimbi (“whistle” in Swahili) citizens’ movement to one year in prison in September. Carbone Beni, Grâce Tshunza, Cédric Kalonji, Palmer Kabeya, and Mino Bompomi were arbitrarily arrested or abducted in December 2017 as they mobilized Kinshasa residents for nationwide protests on December 31, 2017. Kabeya was freed in September. The four others finished serving their sentence on December 25.

In November, authorities arrested and detained for a few days 17 pro-democracy activists in Kinshasa. They also abducted and tortured a LUCHA activist in Goma, who was released after three days.

Government security forces across the country forcibly dispersed opposition campaign rallies ahead of the national elections. From December 9 to 13, security forces killed at least 7 opposition supporters, wounded more than 50 people, and arbitrarily detained scores of others.

Attacks on Civilians by Armed Groups and Government Forces

More than 140 armed groups were active in eastern Congo’s North Kivu and South Kivu provinces, and many continued to attack civilians, including the largely Rwandan Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) and allied Congolese Nyatura groups, the Ugandan-led Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), the Nduma Defense of Congo-Renové (NDC-R), the Mazembe and Yakutumba Mai Mai groups, and several Burundian armed groups. Many of their commanders have been implicated in war crimes, including ethnic massacres, rape, forced recruitment of children, and pillage.

According to the Kivu Security Tracker, which documents violence in eastern Congo, assailants, including state security forces, killed more than 883 civilians and abducted, as well as kidnapped for ransom, nearly 1,400 others in North Kivu and South Kivu in 2018.

In Beni territory, North Kivu province, around 300 civilians were killed in nearly 100 attacks by various armed groups, including the ADF.

In May, unidentified assailants killed a park ranger and kidnapped two British tourists and their Congolese driver in eastern Congo’s Virunga National Park. The park has since been closed for tourism. The tourists and driver were later freed.

Between December 2017 and March 2018, violence intensified in parts of northeastern Congo’s Ituri province, where armed groups launched deadly attacks on villages, killing scores of civilians, raping or mutilating many others, torching hundreds of homes, and displacing an estimated 350,000 people.

Also in northeastern Congo, the Ugandan-led Lord’s Resistance Army continued to kidnap large groups of people and commit other serious abuses.

In December, large-scale ethnic violence broke out in Yumbi, in western Congo’s Mai-Ndombe province, leaving reportedly hundreds dead in a previously peaceful region.

During the December elections, state security forces and armed groups in eastern Congo’s North Kivu province intimidated voters to vote for specific candidates.

Justice and Accountability

The trial of Bosco Ntaganda, accused of 13 counts of war crimes and five counts of crimes against humanity allegedly committed in northeastern Congo’s Ituri province in 2002 and 2003, continued at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the Hague.

In June, an ICC appeals chamber overturned the war crimes and crimes against humanity convictions against former Congolese Vice President Jean-Pierre Bemba for crimes committed in neighboring Central African Republic. In September, the court sentenced Bemba on appeal to 12 months for a related conviction of witness tampering. Interpreting witness tampering as a form of corruption prohibited by the Congolese electoral law for presidential candidates, Congo’s electoral commission later invalidated Bemba’s presidential candidacy in what appears to be a politically motivated decision.

Sylvestre Mudacumura, military commander of the FDLR armed group, remained at large. The ICC issued an arrest warrant against him in 2012 for nine counts of war crimes.

The Congolese trial into the murders of UN investigators Michael Sharp and Zaida Catalán and the disappearance of the four Congolese who accompanied them in 2017 in the central Kasai region was ongoing at time of writing. A team of experts mandated by the United Nations secretary-general to support the Congolese investigation had not been granted the access or cooperation needed to effectively support a credible and independent investigation. Human Rights Watch research implicates government officials in the murders.

A UN Human Rights Council-mandated investigation into the broader, large-scale violence in the Kasai region since 2016 found that Congolese security forces and militia committed atrocities amounting to war crimes and crimes against humanity. In July, the council called on the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to dispatch a team of two international human rights experts to monitor and report on the implementation by Congolese authorities of the Kasai investigation’s recommendations.

The trial against Congolese security force members arrested for allegedly using excessive force to quash a protest in Kamanyola, eastern Congo, in September 2017, during which around 40 Burundian refugees were killed, and more than 100 others wounded, had yet to begin at time of writing.

The trial of militia leader Ntabo Ntaberi Sheka, who surrendered to the UN peacekeeping mission in Congo (MONUSCO), began on November 27. Sheka was implicated in numerous atrocities in eastern Congo, and he had been sought on a Congolese arrest warrant since 2011 for crimes against humanity for mass rape.

In July, Kabila promoted two generals, Gabriel Amisi and John Numbi, despite their long involvement in serious human rights abuses. Both generals have also been sanctioned by the United States and the European Union.

Key International Actors

In 2018, the UN Security Council, which visited Kinshasa in October, the UN secretary-general, the African Union, the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the US, the EU, and many individual states called for the electoral calendar to be respected. They emphasized the need for full respect of the New Year’s Eve agreement, including the confidence building measures, and for the elections to be credible and inclusive.

Belgium announced in January 2018 that it was suspending all direct bilateral support to the Congolese government and redirecting its aid to humanitarian and civil society organizations.

Angolan Foreign Minister Manuel Domingos Augusto said in August that Kabila’s decision not to make an unconstitutional bid for a third term was “a big step,” but that more needed to happen “for the electoral process to succeed and achieve the objectives that have been set by the Congolese.” At a SADC summit in Namibia in August, the Namibian president and new SADC chairman, Hage Geingob, said that the crisis in Congo could lead to more refugees fleeing to neighboring countries if it was not resolved.

In December 2017, the US sanctioned Israeli billionaire Dan Gertler, one of Kabila’s close friends and financial associates who “amassed his fortune through hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of opaque and corrupt mining and oil deals” in Congo, as well as several individuals and companies associated with Gertler. In June 2018, the US announced the cancellation, or the denial, of the visas of several Congolese officials, due to their involvement in human rights violations and significant corruption related to the country’s electoral process.

On December 28, the government expelled the EU ambassador, Bart Ouvry, with 48-hours’ notice. This followed EU’s decision on December 10 to renew sanctions against 14 senior Congolese officials, including the ruling coalition’s presidential candidate, Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary.