Summary

On September 28, 2024, Anastasia Pavlenko, a 23-year-old mother of two, was cycling to an appointment in the city of Kherson in southern Ukraine, near the front line with Russian forces, when she saw a drone take off from the roof of a house and start to follow her. The drone tracked Pavlenko for nearly 300 meters. As she approached the Antonivka Bridge, the drone dropped a munition, which struck the ground nearby and exploded, injuring her in the neck, leg, and rib. In shock, Pavlenko continued on her bike toward the underpass, covered in blood and with flat tires, she later recalled.

Human Rights Watch verified two videos, uploaded to Russian military-affiliated Telegram channels, with footage recorded by the drone used to attack Pavlenko. In one video, Pavlenko can be seen on her bicycle, swerving on the road as the drone follows her for at least 13 seconds. Approximately 50 meters before the bridge underpass, the drone drops a munition that detonates a couple of meters to her left. Pavlenko, still on her bicycle —at this point injured, as it later became known— continues toward the underpass, and the video cuts a few seconds later.

Pavlenko said she received first aid before being taken to a hospital in the neighboring Mykolaivska region, where doctors operated on her broken leg. When Human Rights Watch spoke to Pavlenko in late November, she still had a metal fragment in her neck that surgeons could not remove. She has not been back to Kherson since the attack. “If not for the drones, I would still live there,” she said.

The attack on Pavlenko is just one of several hundred attacks on civilians and civilian objects in Kherson since June 2024, carried out by Russian forces using small, easily maneuverable quadcopter drones armed with explosive weapons, including grenades and antipersonnel landmines, as well as incendiary weapons. The drones send live video feeds back to their operators, who control the drones’ flight and use of weapons with deadly precision from up to 25 kilometers away.

The city of Kherson is located in the south of Ukraine, on the right (northern) bank of the Dnipro River, which has served as a topographical divide between Ukrainian and Russian forces in the area. The city district of Dniprovskyi and the adjacent suburb of Antonivka both sit on the Dnipro River’s right bank.

In March 2022, Russian forces captured Kherson and occupied it until November 2022, when Ukrainian forces retook control of the city and parts of the Khersonska region. During the occupation, Russian forces perpetrated abuses against the civilian population in Kherson. Since Russian forces were forced out of Kherson city, they have maintained positions a few kilometers south on the left (southern) bank of the Dnipro, from where they have continued to fire artillery and launch airstrikes into the city.

Ukrainian forces are positioned throughout Kherson, including in Antonivka and Dniprosvkyi. From their positions they fire upon Russian forces, including Russian drones that fly into the city. The Ukrainian military also assist police and rescue workers in areas most prone to drone attacks, aiding in the evacuation of civilians and demining operations.

Human Rights Watch documented at least 45 drone strikes by Russian forces in Antonivka and Dniprosvkyi that appeared to deliberately target civilians and civilian objects including infrastructure. In eight cases, Human Rights Watch corroborated witness accounts with videos of drone attacks posted to Russian military-affiliated Telegram channels. The videos of these and other attacks on civilians and civilian objects show that the nature of the target was known to the drone operator, indicating a deliberate attack.

The drone attacks detailed in this report were all carried out using quadcopter drones. Unlike larger drones previously used in conflict zones, quadcopter drones are more maneuverable, with a significantly shorter range, but relatively inexpensive and often commercially available. Quadcopter drones can take off and land vertically, follow speeding vehicles, and fit between narrow spaces, all while carrying small munitions. Many of the quadcopter drones mentioned in this report measure less than 40 centimeters diagonally and can be operated using a smartphone or a handheld-controller. Their range is typically between 5 and 25 kilometers.

Starting in June 2024, Russian forces increasingly used quadcopter drones to attack civilians and civilian objects in Kherson. Between May 1 and December 16, 2024, drone attacks in Kherson resulted in at least 30 civilians killed and another 483 injured according to the Kherson City Council Executive Committee. The attacks continue at time of writing.

Russian forces have attacked civilians using quadcopter drones while they were out cycling like Pavlenko, while walking, driving, taking public transport to and from work, and in their homes. They also targeted healthcare facilities, ambulances and their personnel, including rescue workers responding to previous drone attacks on civilians. Russian forces also carried out drone attacks on grocery stores and vehicles delivering produce to stores, forcing nearly all stores in the affected areas to close. Drone attacks on gas, water, and electrical infrastructure—and on municipal workers attempting to repair the damage—have further limited residents’ access to basic services. These attacks have also hampered efforts to clear landmines and other explosive remnants of war.

The attacks have caused deaths and injuries to civilians and widespread fear among Kherson’s population, and caused residents to flee to districts further from the front line and deeper into the city of Kherson. Those who remain—mostly older people and those unable to easily evacuate—are afraid to leave their homes. They say that when they do, they are constantly listening for the buzzing sound of drones overhead, scanning the area around them for potential hiding spots under trees, and looking out for landmines on the nearby ground that may have been dropped during previous drone attacks.

International humanitarian law, also known as the laws of war, prohibits attacks intentionally targeting civilians and civilian objects. Nevertheless, Russian forces using drones have frequently made individual civilians and civilian property and infrastructure in Kherson the targets of attacks. Russian drones have been armed with banned antipersonnel landmines and been used to carry out attacks with incendiary weapons in populated areas, which is unlawful. Such attacks, when viewed individually, are violations of the laws of war that when committed with criminal intent constitute war crimes. Examined in their totality and over time, the pattern of attacks appears to be part of an apparent Russian strategy whose primary purpose has been to spread terror among the civilian population.

Human Rights Watch also found that Russian forces committed apparent crimes against humanity in Kherson by attacking civilians using quadcopter drones. Those attacks resulting in murder or intentionally causing serious bodily or mental or physical health injuries, were carried out as part of a widespread attack on the civilian population in Kherson, and appear to have been in furtherance of a Russian policy behind that attack.

The ability of Russian forces to arm relatively inexpensive and commercially available drones to carry out illegal attacks underscores the urgency of identifying effective ways to enforce respect for international humanitarian law, including through prosecutions of war crimes. Governments should also work with commercial drone companies to develop and implement safeguards to prevent or minimize drones being used for unlawful combat purposes.

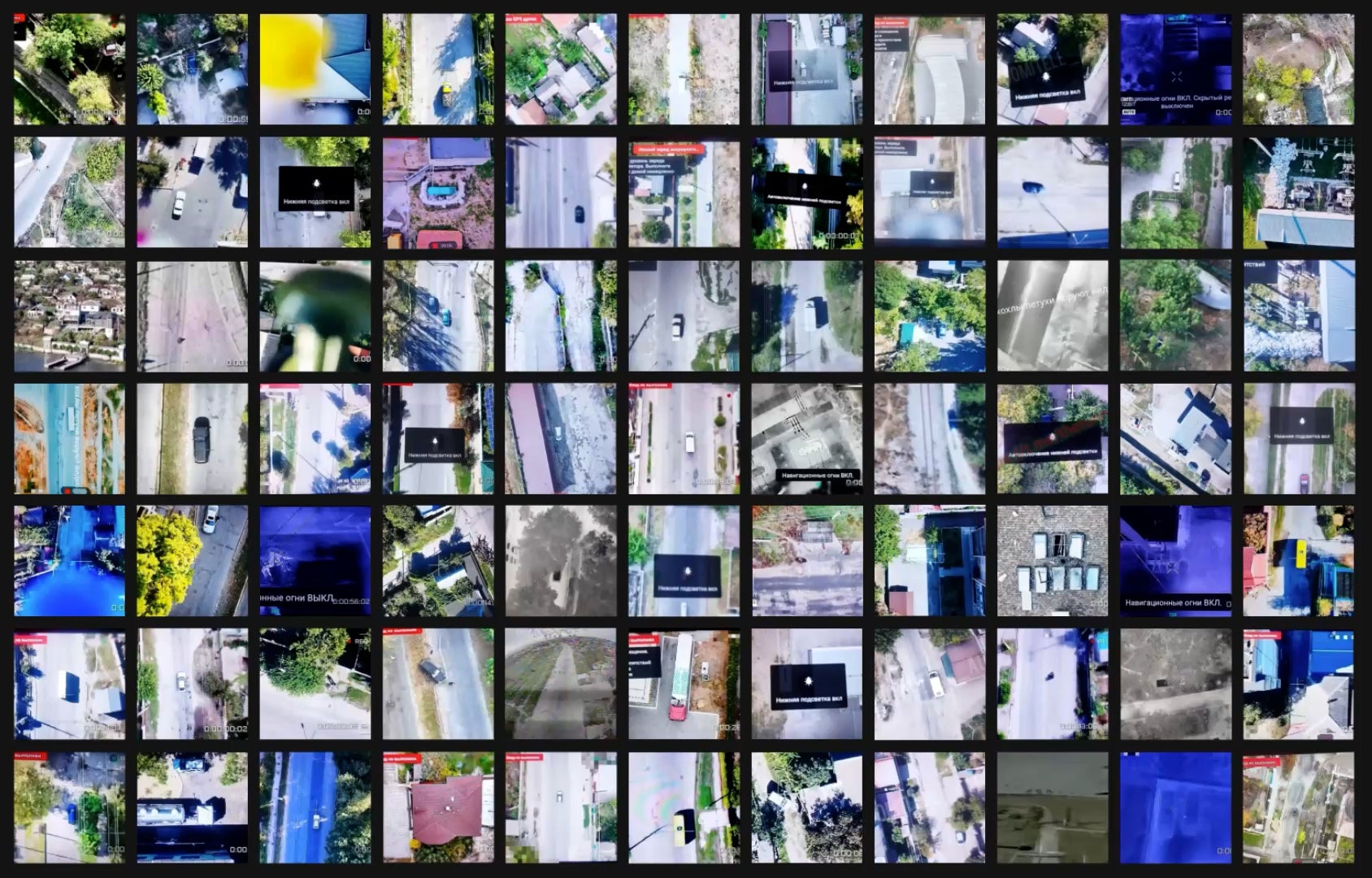

Human Rights Watch’s findings are based on interviews with 59 people, most in person in Kherson, Ukraine in November 2024 and others remotely between October 2024 and March 2025. This includes 36 survivors of and witnesses to Russian drone attacks. Human Rights Watch also analyzed 83 videos of drone attacks uploaded to Russian military-affiliated Telegram channels as well as videos and photographs taken by witnesses and shared with researchers. In April 2025, Human Rights Watch sent a letter with a summary of its findings and questions to the Russian government. It had not received a response at the time of finalizing this research for publication.

Human Rights Watch identified quadcopter drones manufactured by three different entities used by Russian forces in attacks on civilians in Kherson: two China-based commercial drone companies, DJI and Autel, and one model made by a Russian entity named Sudoplatov, which describes itself as a “volunteer organization.” Responding to letters from Human Rights Watch, both DJI and Autel acknowledged reports that their drones were being used by Russian forces for combat purposes, stressed that such use was incompatible with the policies of their companies, and provided information on steps they take to avoid their drones potentially being used for such purposes.

In mid-2024, Telegram channels apparently affiliated with or supportive of the Russian military and specific Russian military units increasingly posted videos of drone attacks on vehicles and people in Kherson. Also posted were maps in which areas—including Antonivka and Dniprovskyi where many civilians were still living—were marked in red. The posts stated that these “red zones” were areas within which Russian forces would target any moving vehicle and should therefore be considered unsafe for civilians. Such posts do not constitute lawful warnings as they falsely imply civilians can legitimately be targeted. Civilians in areas of hostilities remain fully protected from attack, and attacking forces must still take all feasible precautions to avoid loss of civilian life and property. This includes canceling an attack when it becomes apparent that the target is civilian.

Russian use of armed quadcopter drones in Antonivka and Dniprovskyi has hindered civilian access to essential goods and services such as food, medical, and rescue services. Residents told Human Rights Watch that, starting in June 2024, Russian drone attacks on grocery stores in Antonivka and Dniprovskyi caused them to shut down. By November, most had closed or relocated to safer areas, forcing residents to travel long distances, including through the “red zone,” to purchase basic goods and obtain other basic services, putting them at greater risk from drone strikes or shelling.

Medical and ambulance staff said these attacks have had severe effects on people’s ability to access health care, including those injured in Russian attacks. Russian forces have also used drones to attack rescue vehicles and fire trucks responding to fires and other emergencies in these areas.

Russian drone attacks have also targeted public buses, damaging them and injuring drivers. One resident said that as of October 2024, buses no longer traveled into much of Antonivka due to the risk of being attacked.

The Kherson City Council Executive Committee told Human Rights Watch that between May and mid-December, there were at least 24 Russian drone attacks on gas, water, and electrical infrastructure sites. During the same period, Russian drone attacks killed or injured at least five municipal workers as they attempted to repair damaged water infrastructure sites. Altogether, the attacks prevented municipal workers from repairing 37 such sites, the committee said.

Some residents have decided not to drive anymore but say not using cars is also risky. Nastya, an ambulance medic who lives in Antonivka, said:

I am taking the bicycle and don’t drive the car because all my neighbors’ cars have been damaged… But the drones are hunting cyclists as well… People are limiting their visits to the shops. Where I live, there are no shops, and [there is] no way of getting goods delivered there.

To minimize the risk of being harmed, many residents said they reduce the time they spend outside their homes. But even if they do not hear drones overhead, they are at risk of stepping on landmines dropped by drones, they said.

Residents said the attacks and threat of drones have affected their mental health. Husband and wife Valeriy Sukhenko and Anastasia Rusol were injured in a drone attack on their home on November 17. Both said they were deeply psychologically affected by the attack. Sukhenko said he was suffering from nightmares. Rusol said, “I start doing something and then I just stop. I am disoriented and lost.”

The overwhelming effect of these drone attacks and the resulting conditions has been to force civilians to leave the area. Between May and December 2024, Antonivka’s population decreased from 4,570 residents to 2,300, according to the Kherson City Council Executive Committee. Most of the depopulation occurred in November and December, when 1,700 residents of the 4,000 who remained fled for other locales.

Russian forces should immediately cease all unlawful drone attacks on civilians and civilian objects, including those using unlawful munitions. States have an obligation to investigate individuals within their forces or on their territory implicated in war crimes and appropriately prosecute those responsible. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any efforts by the Russian government to credibly investigate or stop attacks on civilians and civilian objects.

Recommendations

To Russia

Abide fully by international humanitarian law, including the prohibitions on attacks that are directed against civilians and civilian objects; that do not distinguish between civilians and military objectives; or are expected to cause civilian harm disproportionate to the anticipated military advantage;

As required under international humanitarian law, take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians and civilian objects, including giving effective advance warnings of attacks when possible;

Ensure all drone operators are adequately trained in international humanitarian law and are aware of the sanctions for those that violate the law;

Do not use internationally prohibited weapons in drone attacks, including antipersonnel landmines, and join the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty;

Ensure that all units deploying drones maintain flight logs and make them accessible to any oversight bodies within the military or the broader government that has a mandate to investigate the lawfulness of attacks;

Support independent and impartial investigations into credible allegations of laws-of-war violations, including the incidents detailed in this report;

Make information public regarding the intended military targets of strikes that resulted in civilian casualties, and those that directly or indirectly damaged civilian infrastructure and other protected objects;

Make public the findings of investigations into attacks resulting in civilian casualties, and take disciplinary action or pursue criminal prosecution as appropriate where violations are found;

Provide prompt and appropriate compensation to civilians and their families for deaths, injuries, and property damage resulting from unlawful strikes. Consider providing “ex gratia” payments to civilians who suffered harm from strikes without regard to possible wrongdoing.

To Ukraine

Ensure emergency personnel, volunteers, and other civilian professions working in areas prone to Russian drone attacks have access to personal protective equipment that is clearly distinguishable from Ukrainian military gear;

If using civilian vehicles for military purposes in populated areas prone to Russian drone attacks take measures to distinguish those vehicles from other civilian vehicles;

Abide fully by international humanitarian law in any use of drones. In the event that Ukrainian forces use drones for armed attacks, do not use internationally prohibited weapons, such as antipersonnel landmines, in such attacks.

To All States

Consider targeted sanctions against senior officials and commanders credibly implicated in serious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law;

Support foreign and domestic investigations and prosecutions under the principle of universal jurisdiction, as relevant and appropriate, of those credibly implicated in serious crimes in Ukraine;

Publicly support the work of the International Criminal Court in its ongoing Ukraine investigation. Uphold the court’s independence and publicly condemn and counter efforts to intimidate or interfere with its work, officials, and those cooperating with the institution;

Contribute to efforts to secure justice and compensation for victims through reparations, including through the work of the International Claims Commission set up at the Council of Europe;

Reject amnesty for serious crimes under international law, including war crimes and crimes against humanity, in any peace negotiations;

Support authorities in areas where drones attacks are being carried out, to ensure they have systems in place to clear and destroy drone remnants safely, including unexploded ordnance and when the drone fails to return to the location of the operator;

Maintain comprehensive flight logs of drones used in military operations and ensure these records are accessible to oversight bodies within the military or broader governmental entities authorized to examine the legality of such operations;

Allow investigators access to drone logs when attacks are investigated;

Continue supporting Ukraine’s mine clearance and risk education work and efforts to evacuate the civilian population from areas affected by hostilities, as well as providing medical, social, and other assistance to civilians injured as a result of the hostilities and ensuring their basic humanitarian needs are met.

To Commercial Drone Companies

Have in place a process by which the public can share with the company allegations of use of the drones in armed attacks, in particular use in alleged unlawful attacks;

Share allegations of use of drones in combat, in particular unlawful attacks, with authorized retailers and require authorized retailers, as part of contractual agreements, to respond to allegations of use of the drones in unlawful armed attacks by their clients, including by engaging with clients about how such use violates the terms of use or sale, and restricting any future sales to prevent risk of further use in unlawful attacks;

Comply with requests from national, regional or international judicial authorities to assist in interpreting drone logs or other technical questions arising in the course of investigations into potentially unlawful attacks using drones;

Cooperate with and provide technical information to governments developing future norms around the use of drones adapted to deliver weapons.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch interviewed 59 people for this report, most in person in Kherson, Ukraine in November 2024, and others remotely between November 2024 and March 2025. This includes 36 survivors of and witnesses to Russian drone attacks. Human Rights Watch also spoke to rescue workers and medical staff who treated drone attack victims; municipal workers; officials from the city districts affected by the attacks; local journalists; and Ukrainian regional authorities.

Interviews were primarily conducted in Ukrainian with the assistance of interpreters, and in English.

Researchers informed all interviewees about the purpose and voluntary nature of the interviews, and the ways in which Human Rights Watch would use the information. We obtained consent from all interviewees, who understood they would receive no compensation for their participation. The names of some interviewees have been disguised with first names and surname initials which do not reflect their real names, in the interest of their privacy.

On April 14, 2025, Human Rights Watch sent a letter with a summary of its findings and questions to the Russian government and followed up in May, but it had not received a response at the time of finalizing this research for publication.

From November 2024 to April 2025, Human Rights Watch sent letters to various Ukrainian authorities with questions related to the attacks. Two responses were received, and relevant information is reflected throughout the report

Human Rights Watch sent letters to two China-based commercial drone companies, DJI and Autel, and one Russian entity, Sudoplatov, whose products were identified in attacks on civilians. DJI and Autel both responded in April to Human Rights Watch and their correspondence is included in full in the appendix, and reflected in the report. Human Rights Watch had not received a response from Sudoplatov at the time of finalizing this report for publication.

Human Rights Watch analyzed 83 videos of drone attacks uploaded to Russian military-affiliated Telegram channels. We analyzed 60 videos and photographs taken by witnesses and shared with researchers. We also analyzed 21 photographs and 7 videos posted to social media platforms. As per our standard methodology, each video and photograph analyzed by open-source researchers at Human Rights Watch was then reviewed by members of staff with visual verification expertise. To determine the location of each video and photograph, researchers matched landmarks with available satellite imagery, street-level photographs, or other visual material. Where possible, Human Rights Watch used the position of the sun and any resulting shadows visible in videos and photographs to estimate the time the content was recorded. Researchers also confirmed that each piece of content had not appeared online prior to the date it was posted, using various reverse search image engines.

Human Rights Watch has adopted specific terminology to distinguish between audiovisual content that we have analyzed and audiovisual content that we have also verified. In the report, Human Rights Watch uses the term “reviewed” for content that has been seen but has not gone through several verification checks. We use the term “analyzed” for content that has been reviewed and appears authentic, but for which we have confirmed some but not all temporal, geographic, or contextual aspects. We use the term “verified” for videos or photographs where we were able to confirm the location, timeframe, and context in which they were taken.

Human Rights Watch has preserved the photographs and videos referenced in the report. Where possible, Human Rights Watch has included direct links to social media posts in the relevant footnotes. Human Rights Watch did not include links to online content that might pose a security risk for the people seen in the content or the person posting it. Human Rights Watch also did not include links to content deemed too distressing to maintain the dignity of those shown and minimize readers' exposure to violent and distressing content.

Researchers examined a variety of Russian military-affiliated Telegram channels with a particular focus on Russian military operations in Kherson. For Russian units participating in the war, Telegram is the predominant method for sharing uncensored videos and photos. From these channels, researchers selected videos that appeared, based on specific criteria related to buildings and landscape, to have been filmed in the city, and not other parts of the region. Most videos that researchers found of Russian drone strikes in Kherson were posted to the Telegram channels listed below.

Human Rights Watch categorized the videos it reviewed based on whether the attacks they showed were on people, vehicles, houses, or services. We did not research drone attacks on distinct military targets. In many cases, we could not determine if civilian objects targeted in the attacks such as vehicles or houses were being used by civilians. This was often because the video lacked contextual information such as people and their attire or the video was of poor quality.

When possible, Human Rights Watch identified the type of drone involved in each video documented in this report. Researchers matched elements on the drone’s interface—such as the mini-map, typeface, and other textual components—with known examples provided by the drone manufacturer on their websites or on their social media accounts.

Russian Military-Affiliated Telegram Channels

Most of the videos of drone attacks reviewed by Human Rights Watch were uploaded to the following Telegram channels. Human Rights Watch could not confirm the identity of the person or persons behind the following channels.

“From Mariupol to the Carpathians” Telegram Channel

The “From Mariupol to the Carpathians” channel is a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel created on or around June 5, 2022. The person or people behind the account began posting about the Russian occupation of Kherson the same month. The account, which had more than 50,000 followers at time of writing, routinely posts about Russian military operations in the city and the region. It has run fundraising campaigns to provide military equipment, in particular drones, to specific Russian units operating in the Khersonska region. The channel has been the primary source sharing many of the drone attack videos originating from Kherson.

“Dnepr” Telegram Channel

The “Dnepr” Telegram channel is a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel created on November 19, 2021, with more than 35,000 followers at time of writing. The channel’s description says it is the official channel for Russia’s “Dnepr” forces. These forces were reportedly established in 2023 and are responsible for the Russian military’s operations in the Khersonska region.

“Habr” Telegram Channel

The “Habr” channel was a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel created on September 6, 2024, with more than 13,000 followers at time of writing. Posts published to the channel claimed it was run by a Russian Armed Forces drone operator belonging to a drone unit also called Habr, which the channel claims was established in May 2024, under the command of the 18th Combined Arms Army. In early March 2025, the channel changed its name from “Habr” to “Sueta” and at the same time a second Telegram channel was established under the Habr username. Those behind both channels have posted numerous drone videos showing Russian attacks in Kherson.

“Moses” Telegram Channel

The “Moses” Telegram channel is a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel created on September 10, 2022, with more than 66,000 followers at time of writing. It is associated with Russian military drone operations and the person or people behind the account have been posting about Kherson since the channel was created.

Background

On March 2, 2022, Russian forces captured the city of Kherson, which sits on the right (northern) bank of the Dnipro River.[1] They occupied the city, which prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion 10 days earlier was home to roughly 280,000 people, until November 2022, when Ukrainian forces retook control of it.[2] During the period of occupation, Russian forces perpetrated a range of abuses against the civilian population, including arbitrary detention, torture, and looting, including of cultural institutions.[3]

Since November 2022, Russian forces have maintained positions across the Dnipro River, a few kilometers south of the city, from where they continue to fire explosive weapons into the city, killing and injuring civilians. These attacks also damaged the city’s water, electricity, and telecommunications infrastructure, restricting residents’ access to these services.[4]

The areas of Antonivka and Dniprovskyi are located in the eastern part of Kherson, adjacent to each other, and extending to the Dnipro River. Ukrainian forces are positioned throughout Kherson, including in Antonivka and Dniprosvkyi. From their positions they fire upon Russian forces, including Russian drones that fly into the city. The Ukrainian military also assist police and rescue workers in areas most prone to drone attacks, aiding in the evacuation of civilians and demining operations.

In June 2024, Telegram channels apparently affiliated with the Russian military and specific Russian military units began posting videos of drone attacks on people and vehicles in Kherson. They also shared maps of the city showing Antonivka and Dniprovskyi marked in red, calling them “red zones,” where Russian forces would target any moving vehicle, and which should therefore be considered unsafe for civilians. Many of these videos were posted with the message:

Any movement of motor vehicles will be considered a legitimate target.

All critical infrastructure facilities are a legitimate target. Civilians should be extremely attentive and careful. Limit your movements, leave the area if possible.[5]

Such warnings are unlawful because civilians remain fully protected from attack, and attacking forces cannot designate areas “civilian free zones.” They must still take all feasible precautions to avoid loss of civilian life and property. This includes canceling an attack when it becomes apparent that the target is civilian.

Attacks on Civilians in Kherson

Residents of Kherson told Human Rights Watch that Russian drone attacks on the areas closest to the Dnipro riverbank in Dniprovskyi and Antonivka became more intense in June 2024.[6] They described attacks taking place on civilians who were walking, cycling, or driving in their neighborhoods, and when they were in their homes.[7] Some recounted how they tried to hide or evade a drone that followed them for several minutes, including by driving evasively or hiding under trees.[8] Others said they had seen drones sitting stationary, which conserves battery life, on rooftops in the city before operators dispatched them to fly and attack.[9] Human Rights Watch also spoke to residents in Antonivka who said that in August 2024, drones began scattering antipersonnel landmines in their neighborhoods, which injured civilians and damaged civilian objects.

Between May 1 and December 16, 2024, drone attacks in Kherson resulted in at least 30 civilians killed and another 483 injured according to the Kherson City Council Executive Committee.[10] The drone attacks continued at time of writing. Drone attacks accounted for 70 percent of civilian casualties recorded in Kherson in January 2025 by the United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (HRMMU).[11]

Attacks on Civilians Walking and Bicycling

Human Rights Watch interviewed three civilians ages between 22 and 56 who were injured in Russian drone attacks while walking or cycling on streets in Antonivka. All of them described how drones followed them for several hundred meters or hovered over them before and after attacking.[12]

Anastasia Pavlenko, 23, is a mother of two who used to live in Antonivka and worked at a coffee shop in Kherson.[13] She moved to Lviv during the Russian occupation of Kherson in 2022 and returned to Antonivka after the de-occupation to bury her father.

On September 27, Pavlenko was followed by a drone while walking but managed to escape unharmed. The next day, she was cycling along the main road between Antonivka and Kherson. “Suddenly,” she said, “I saw a drone take off from a roof and start to chase me.” The drone followed Pavlenko for nearly 300 meters. She said she was still on her bicycle and less than 100 meters from the Antonivka bridge when “the drone dropped a grenade. I was injured in my neck, left leg, and under the rib.” In shock, Pavlenko continued toward the underpass. “I was still biking, covered in blood and with flat tires,” she recollected.[14]

The same day, a video showing the attack on Pavlenko was uploaded to a Russian military-affiliated telegram channel.[15] The three-second verified video of a handheld recording of a still drone image on a computer screen shows a person on a bicycle. It is captioned:

Ukrainian Armed Forces soldiers ride bicycles. This character was accurately eliminated… [Medical] Evacuation is not allowed to approach.

Twelve days later, on October 9, a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel uploaded a longer video of the same drone feed that Human Rights Watch verified.[16] The video shows a drone with the camera pointing straight down, tracking Pavlenko on her bicycle. Researchers matched the video with the still image in the video described above, and Pavlenko confirmed to Human Rights Watch that both videos showed the drone attack on her.[17] In the second video, Pavlenko can be seen on her bicycle, swerving on the road as the drone follows her for at least 13 seconds. Approximately 50 meters before the bridge underpass, the drone drops a munition that detonates a couple of meters to her left. Pavlenko, still on her bicycle, continues towards the underpass and the video cuts a few seconds later.

Pavlenko said she received first aid at a military checkpoint in the underpass from military personnel, after which she was taken to a hospital in the neighboring Mykolaivska region, where doctors operated on her broken leg.[18] When Human Rights Watch spoke to Pavlenko in late November, she had moved to a different city, and said she still had a metal fragment in her neck that surgeons could not remove due to its position.[19] Pavlenko spent seven days in the hospital. She has not been back to Kherson since. “If not for the drones, I would still live there,” she said.[20]

Tetiana Kravchuk, a lawyer from Antonivka, said she left home on foot on October 30, 2024, at 6:30 a.m., to go feed her neighbor’s dog.[21] Her son’s car had been damaged the previous day when he drove it over a landmine. Kravchuk checked the street for landmines, as she feared a drone might have emplaced some overnight. As she was returning to her house, she heard a drone. Kravchuk said:

It was behind me, chasing me. I tried to hide between the trees. I heard the drone circling the tree, coming closer and closer. The drone was four meters above me. Then there was an explosion.

Kravchuk said, “I called my son and told him that a drone had attacked me, and my leg was injured.” Seven minutes later, Kravchuk’s son arrived and took her to the hospital in Kherson, where she underwent surgery and spent six days. When Human Rights Watch interviewed Kravchuk in late November, she was still being treated, after which she was to begin six months of rehabilitation.

Andrii Loukin, 22, is from Antonivka and works as a car mechanic in the suburb.[22] One day in late September, Loukin was cycling home from work when, he said:

I heard the drone. It sounded like a swarm of bees. It was chasing me. I tried to escape, but I was unsuccessful. I saw the drone—it dropped a grenade on me. I fell off the bicycle because both tires were punctured. The drone hovered over me for several minutes before leaving.

The attack wounded Loukin with metal fragments in his left hand, chest, and right leg. “Luckily, they were not deep,” he said of his wounds.

In addition to the previously described attacks, Human Rights Watch analyzed 10 drone videos posted to Russian Telegram channels between August 2024 and January 2025 showing drone attacks on people in civilian clothes and apparently unarmed walking or cycling in Dniprovskyi and Antonivka.[23] Researchers corroborated three attacks seen in videos using media articles and statements from local officials and organizations.

One verified video uploaded to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel on October 9 shows a drone attack on two individuals on a street in Dniprovskyi District.[24] Human Rights Watch analyzed shadows visible in the video that suggest the drone attack happened around midday. The footage shows a drone flying towards two pedestrians; both appear to be civilian and unarmed. As a cyclist, also in civilian clothes, passes by, the drone drops a munition that lands just a meter to the right of one of the pedestrians. Both pedestrians collapse to the ground, clutching their legs, apparently injured. The drone hovers above the two individuals for 15 seconds before flying away as the video ends. Part of the video's caption says:

Civilians should be extremely attentive and careful. Limit your movements, leave the area if possible.

Roman Mrochko, head of the Kherson City Military Administration, posted to his Telegram channel that on October 9, at around 1 p.m., two men, ages 40 and 46, received injuries to their legs from a Russian drone attack in Dniprovskyi District.[25]

One analyzed drone video uploaded to a Russian military-affiliated telegram channel on November 18 shows a drone attack on two apparently unarmed individuals in civilian attire standing next to each other on a small road in Antonivka.[26] The footage starts with a drone hovering above the two people. They see the drone and begin running away from it. The drone follows them for a few meters and then releases a munition. One person falls to the ground, stretches out an arm, and then goes motionless. A day prior, on November 17, the same Telegram channel posted a screenshot from the same drone video.[27]

Attacks on Civilian Vehicles

Human Rights Watch interviewed 15 survivors or witnesses of drone attacks that took place as people were driving or immediately after they had parked, or attacks on stationary vehicles, in which two people were killed and four were injured. The victims ranged in age from 27 to 75. Residents recounted how drones followed their cars for several minutes, as they tried to speed away and change direction.[28] In cases where they were unable to evade the drone, it eventually dropped munitions directly on or beside their vehicle, causing death and injury.[29]

Nataliia, 25, previously lived in Antonivka but moved to another part of Kherson in 2022 for work.[30] Her father, Petro, 67, together with his wife and Nataliia’s mother, Tetiana, owned “Natali,” a grocery store on Khersonska Street in Antonivka named after their daughter. Tetiana ran the store and Petro drove her to work every morning and picked her up in the late afternoon.

“August 26 [2024] was a normal day,” Nataliia said. “We talked on the phone. He [Petro] had just taken my mom to work and was returning home in our white Mercedes Sprinter minivan. This van was the family’s breadwinner.”

Every morning around 7 a.m., Petro would drop off Tetiana, near the Salut shopping center, from where she would walk the remaining distance to her work. Petro did not want to risk being targeted by drones by driving any further. He would pick her up at the same location at around 4 or 5 p.m. On this day, however, he decided to pick her up closer to her work. Around 6 p.m., Nataliia’s mom called her. Nataliia said:

I heard “Hello,” followed by an explosion. Then the line went dead. I immediately knew something had happened. I rushed out, called 103 [Ukraine’s ambulance hotline], and begged them to help, explaining that an explosion had occurred near Salut [shopping center].[31]

Nataliia shared a drone video, which researchers verified, that had been posted to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel on August 26 at 8:44 p.m.[32] The video shows a drone following and then attacking her parents as they drive in their Mercedes Sprinter van. It starts with a drone flying over houses in Antonivka and a white Sprinter driving approximately a hundred meters in front of the drone. An analysis of the direction of the shadows indicates the video was filmed in the late afternoon. The drone catches up with the van and follows the vehicle for 500 meters. As the van enters the roundabout near Salut shopping center, the drone drops a munition that hits the roof of the van above the driver’s seat and detonates. The vehicle continues straight for a few meters before crashing into an object on the side of the roundabout.

Nataliia went to the O.S. Luchanskyi Kherson City Clinical Hospital on her husband’s suggestion, where she found her mother being treated for a fracture in her left arm. “When I arrived, my mom was sitting there, covered in blood, holding one of my dad’s sneakers close to her heart,” she said. “I didn’t see my dad.”

When Tetiana was taken for an X-ray, an anesthesiologist who knew Nataliia and used to shop in “Natali” approached her. Nataliia said:

She grabbed my shoulder and said, “Your dad is gone.” Then I saw my mom coming out of the X-ray room. They had been together for 32 years, and now I had to tell her that my dad was gone.

The anesthesiologist told Nataliia that the explosion had shattered her father’s skull. Although he was alive on admission to the hospital, Nataliia was told there had been no neurosurgeons in the hospital to treat his severe head injury.[33]

Nataliia went to recover her father’s van from the site of the attack several weeks later. “When we retrieved the van, it started raining as we worked [to remove the vehicle],” she said. “It felt like a sign from my dad, protecting us from the drones.”

Rain affects drones’ flying capabilities and residents told Human Rights Watch that drone attacks were less frequent on rainy days.[34]

Olga Rudchenko, 75, said she was in her apartment building’s backyard disposing of garbage on August 2 at around noon, when she saw her neighbor Serhii Dobrovolskiy, 54, the commercial director of a window company, arrive home and park his car under a tree.[35] Seconds later, Rudchenko said she spotted and heard a drone as it flew over the roof of the nine-story building. She yelled out to warn Dobrovolskiy about the drone. Both dashed toward a nearby tree, hoping it would provide cover from the drone. Dobrovolskiy overtook Rudchenko, who uses a walking cane and cannot run due to a physical disability.

Moments later, she heard an explosion. The drone had dropped a munition on one of the cars parked near the building and detonated.[36] Both Dobrovolskiy and Rudchenko were struck by metal fragments. “I was injured and started to bleed,” Rudchenko said. “I looked over to Serhii and saw him lying on the ground, dead. The ambulance came and I was evacuated, but they left him.” Rudchenko says she was hit in the back, just below the shoulder blade.[37]

Dobrovolskiy’s wife, Angelica Dobrovolska, said her husband was pronounced dead at the scene. A metal fragment from the munition had pierced his heart.[38] Dobrovolska showed researchers a photograph of Dobrovolskiy on the ground, in grey shorts and a blood-stained t-shirt.

This was not the first time cars parked outside of the apartment building had been targeted by drones. Dobrovolska said she and her husband had also witnessed an attack on a parked car on July 24. She did not know if the Ukrainian military had been operating in the vicinity of the apartment building during either attack.[39]

Vitaliy lived in Antonivka before moving to another part of Kherson in January 2025.[40] On October 31, 2024, at around 8 a.m., Vitaliy was driving along the main road in Antonivka, near Molodizhnyi Pliazh, on his way to the Kherson Regional Oncology Center where his mother was undergoing chemotherapy. He said, “While I was driving, a drone caught up with me. I did not hear anything … suddenly the drone hit me, and that was it.”

A verified drone video uploaded to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel on October 31 shows the attack on Vitaliy’s car.[41] The video shows a quadcopter drone flying along the main road in Antonivka, traveling approximately 1.2 kilometers before striking the rear of Vitaliy’s car. The video is captioned:

Kherson. Red zone. Antonivka. Footage of equipment being destroyed on the right bank this morning. Once again.

Any vehicle in the area is a target.

Vitaliy confirmed to researchers that the video showed the attack on his car.[42] He said the drone hit the ground under the fuel tank, smashing the back of the car and completely tearing off the back right wheel.[43] Vitaliy said, “I immediately got out of the car, fearing a second drone might follow and target me. But there was none. I walked away and went to the hospital to see my mother on foot.” Vitaliy said he sustained a concussion in the attack. He shared pictures of his damaged car with Human Rights Watch.

Since Kherson was re-taken by Ukrainian forces in November 2022, Volodymyr Mikhin, 48, has been supporting local communities by driving to various areas in the Khersonska region to deliver donated items including food and clothing.[44] He said he has been the victim of drone attacks on three occasions. The first time was in late November 2023, when he was driving his car, a silver Mercedes van, to Antonivka from Sadove town, approximately five kilometers to the east.

The second attack happened on October 1, 2024, at 11:20 a.m. Mikhin said he had finished a delivery and was standing with a friend smoking a cigarette next to the car, parked under a tree next to a building, when he heard a drone overhead. First, the drone dropped a munition on the roof of the building, damaging the roof. Then it dropped a second munition into the tree. The munition exploded, damaging the tree and the roof of his car.

The third attack happened on the morning of October 15, when Mikhin was driving from his home. Before he left home, his neighbors told him they had not seen or heard any drones that morning. Mikhin said:

As I got to the main street, intuitively I felt something was coming. I stopped to see if there were any other cars around and suddenly there was a big blast about five meters in front of my car. If I had not stopped, it would have hit my roof, and I would have been finished.

Mikhin said his right hand was lacerated by metal fragments and that by the time he reached the hospital, where he drove himself, his driver’s seat was stained with blood. Mikhin said he had seen no Ukrainian military presence in the direct vicinity at the time of the three incidents and had not heard any outgoing Ukrainian fire right before the incidents. He shared pictures of his damaged car with Human Rights Watch.

Viktor Kolisnyk, 58, is a gynecologist at O.S. Luchanskyi Kherson City Clinical Hospital in Dniprovskyi District.[45] He was the victim of a drone attack on September 18 at around 4 p.m., when driving to his home in Dniprovskyi with his wife. “I saw and heard the drone,” Kolisnyk said. “It was in front of me. I began to speed and swerve, changing directions to avoid it.” After several minutes of attempting to escape the drone, there was an explosion near the front of the left side of the vehicle. The car began to smoke and rolled for 100 meters before Kolisnyk and his wife got out. Kolisnyk’s leg was injured by metal fragments in four places. His wife was unharmed, which he said was “a miracle.”

Viktoria Fomina, 47, works as a taxi driver in Kherson.[46] On August 18, 2024, at around 8 a.m., she said she was driving to a home in Antonivka when there was an explosion to the left of her car. She said:

I didn’t understand what was going on. I jumped out of the car and saw the wheels were damaged, and fuel was leaking out. I saw there was damage to the bumper as well. Within minutes, [the Russians] dropped another explosive onto the roof of the car, while I was standing next to it. Luckily, I heard the second drone and ran away right before the car was hit.

Fomina said she could not drive away as her car tires had been damaged. A towing service refused to help move her car, saying the area was too dangerous. A friend then collected Fomina and towed the car to a garage. Fomina said the mechanics found small screws embedded in one of the car’s wheels that may have been inside the munitions dropped by the drone.[47] Fomina shared pictures of her damaged car.

Olha Chernishova, 38, lives by the river in Dniprovskyi and runs a supermarket in Suvorovskyi district, one block north of the river.[48] On September 9 around 4 p.m., she had parked her white Renault van outside her home and was unloading groceries, when she heard a sound that she identified as a drone and ran toward her house. As she reached the door, there was an explosion that propelled her into the house. Her van had been hit and there was a hole above the passenger side. Chernishova shared pictures of the damage to her car and unexploded ordnance she said she found next to it and in her garden after the attack.

Vadim Litvynenko, 46, an entrepreneur, was the victim of a drone attack on September 26 while driving his car in Dniprovskyi District. The attack left Litvynenko with a concussion and damaged his car.[49]

Human Rights Watch also analyzed 42 videos of other individual drone attacks in Kherson on civilian vehicles posted to Russian military-affiliated Telegram channels between August 2024 and January 2025.[50] The videos were frequently captioned with the meaningless warning: “Any movement of motor vehicles will be considered a legitimate target … Civilians should be extremely attentive and careful. Limit your movements, leave the area if possible.”

In most of the drone attack videos, it was not possible to reach a definitive conclusion on whether the vehicle attacked was being used by civilians or by the Ukrainian armed forces, which has used civilian vehicles for military purposes.[51] In three cases, researchers corroborated attacks seen in videos using media articles and statements from local officials and organizations. This cross-referencing indicated that the attacks seen in the videos were attacks on residents or people working in Kherson.

One verified drone video uploaded on September 2 to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel shows a drone attack on a silver SUV driving in Antonivka.[52] The drone tracks the car as it turns onto Molodizhna Street, following it for approximately 200 meters before dropping a munition that hits the left side of the windshield. The car comes to a stop. The video caption warns: “Any movement in the red zone is a trigger for a strike. Any. Assume that your vehicle is a potential target.”[53] An analysis of the shadows visible in the video indicates the attack took place at about 1 p.m.

On the same day, media and local authorities reported that a drone attack killed a recently retired doctor from the Kherson Regional Oncology Center as he and his wife were driving home at about 1 p.m. [54] His wife was injured in the attack.

Another analyzed drone video uploaded to a Russian military-affiliated telegram channel on October 4 shows a drone dropping a munition on a white car being driven along Molodizhna Street in Antonivka.[55] The munition impacts the ground less than a meter to the left of the car. Flames shoot out briefly from underneath the car and as the car slows down. The video ends a few seconds later.

On the same day, Roman Mrochko, head of the Kherson City Military Administration, reported on his Telegram channel that on October 3 a drone attack on a taxi, which appears to be the same vehicle in the drone video, had injured the driver.[56] The post includes a video with several clips. The first one shows a scorched white car of similar dimensions located approximately 230 meters from where the drone attack on the white car in the previous video was. The second clip shows a man speaking from a hospital bed who identifies himself as the driver and describes the injuries he sustained during the attack. He shows a photo of the scorched white car from his phone.

Human Rights Watch analyzed two videos of drone attacks on individuals who were exiting or approaching civilian vehicles in Antonivka, but it was not possible to determine if the people targeted were civilian or military. Drone attacks on military targets are legitimate under international humanitarian law, but the obligation is on the attacking force to take appropriate measures to determine whether the target is military or a protected civilian object. One analyzed video shows two men wearing mostly civilian clothing (one is dressed in camouflage pants) exiting a civilian vehicle after a drone drops a munition near the vehicle.[57] One man pulls an assault rifle from the back of the car and aims it at the drone before the video ends. A second analyzed video shows a drone dropping a munition on a man approaching a civilian vehicle wearing civilian clothing and beige-colored body armor, matching the color of body armor Ukrainian armed forces wear.[58] He runs away, removing his body armor, as the drone follows him. In both cases the targets may have been military, and so Human Rights Watch has not included either case in its accounting of drone attacks on civilians.

Attacks on Civilians in Their Homes

Human Rights Watch interviewed four civilians who were victims of a drone attack while in their homes in Antonivka.

Valeriy Sukhenko, a mechanic, 33, and his wife Anastasia Rusol, currently unemployed, 39, lived in a single-story home in Antonivka.[59]

On November 17 at about 4 p.m., Sukhenko was outside when he heard a drone overhead.[60] He ran inside and within seconds of closing the door, a drone hit the roof and detonated, causing it to collapse and starting a fire. Sukhenko, who was not injured, got a fire extinguisher from his garage. About 10 minutes later, as he and a neighbor were still trying to extinguish the fire, there was another explosion. Sukhenko said:

I saw flames and an explosion and then I don’t remember anything. Then I came to, maybe five seconds later, and saw a second drone fly through the hole the first one had made. I was lying on the ground and understood that I was alive, but also realized blood was pouring down my face. I ran to find my wife.

Rusol was in the kitchen at the time of the attack, with their new chihuahua puppy tucked into the front of her coat, when she heard a smashing noise. She said:

At first, I didn’t understand what was going on, and then I heard my husband calling for me. There was darkness in front of my eyes. I was still standing, somehow shut off from the world. I was so strongly affected by first explosion, that I don’t even remember the second one.61F61F[61]

She opened her coat only to find her dog dead, right in front of her heart, where she had been holding it. A metal fragment had pierced the dog’s body. “Our little dog saved my life,” Rusol said.

Sukhenko’s right leg was wounded in the attack, leaving the bone in his lower thigh exposed.[62] His head, shoulders, back, and arm were also injured, and he suffered third degree hearing loss. Sukhenko said their area had no cell phone reception after a Kyivstar cellular phone tower was damaged in an attack months earlier. A neighbor ran to the nearby church, which had a phone connection, and called the police to take the couple to hospital in an armored vehicle, as it was too dangerous for an ambulance to get them without risking coming under drone attack. It took the police one hour to reach them.

Rusol also has third degree hearing loss as a result of the explosions. She sustained a concussion and suffered deep cuts from metal fragments to her arm, with one part of the muscle above her elbow severed, as well as her left knee and left hand. A fragment also cut off part of her nose.[63]

Later that night, while the couple were still in the hospital, their neighbors told them another drone had dropped a munition on their house after they left, destroying it.[64] “We lost our home. Everything was there. Everything burned down,” Sukhenko said, showing researchers images of the burned out remains of the house.

Sukhenko and Rusol said there were no Ukrainian military positions next to their home, and that they had not heard any outgoing fire before the attack. They said that one week before the attack on their home, there was a drone attack on their neighbor’s home in which a dropped munition killed the neighbor’s dog.

On October 7, Volodymyr Mikhin was standing over the boot of his car outside his garage at home in Dniprovskyi District after a morning of humanitarian aid deliveries.[65] He said he did not hear the drone approaching as he had left the engine running. Suddenly, there was an explosion as a drone released a munition that hit his front gate, damaging it. He heard a popping sound and then the sound of wood and metal splintering. Immediately afterwards, he heard the drone as it dropped lower and ran into his garage as a second explosion hit the front of his home: “The blast wave was strong, I felt like I had been hit by a boxer.” The explosions left Mikhin with a concussion.

Svitlana Valinkevich, 50, lives close to the riverbank in Dniprovskyi District.[66] She said her dog had become accustomed to hiding from drones. On November 17, her dog ran into the house and Valinkevich looked out of the window to see if there was a drone. She heard a thump and saw a munition that had failed to detonate in her garden next to her Christmas tree. The military came a day later and took the unexploded munition away. Valinkevich shared pictures of the item with researchers. She said the same thing had happened on the property of other neighbors.

Three other residents of Antonivka told Human Rights Watch researchers their houses were targeted and damaged in drone attacks while they were not home. In two cases, the residents were in hospital at the time being treated for injuries sustained in other drone attacks.[67]

In each case, the resident said a neighbor had witnessed the attack and the resident shared pictures of the damaged homes with researchers.

Human Rights Watch analyzed six drone videos posted to Russian military-affiliated Telegram channels showing drone strikes on houses and apartment buildings between August and January 2025. There were no indicators in any of the videos or reporting that showed the house was being used by Ukrainian forces.

One drone video uploaded to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel on October 27 shows a quadcopter drone attacking a person in civilian clothing in an apartment building.[68] The video consists of four clips. In the first, a drone crashes into the balcony on the eastern side of a multi-story apartment building in Antonivka. A person in civilian clothing sitting on the balcony stands up. The video pauses before impact and then shows a picture of a pig’s head overlaid onto the person’s head. Two other clips show other drones striking the same building, while the fourth clip shows the building on fire.

Drones Emplacing Antipersonnel Landmines

In August 2024, Kherson’s authorities started issuing warnings through their Telegram channels and by distributing printed information posters in Antonivka, Dniprovskyi, and other affected areas of the city to warn residents about the danger posed by PFM antipersonnel landmines, some emplaced by drones.[69]

Both Russian and Ukrainian forces possess PFM antipersonnel landmines and have used them in the current conflict.[70] PFM antipersonnel mines, also called “petal” or “butterfly” mines, are small plastic blast mines that are delivered by rocket, helicopter, specialized ground vehicles, drones or other means. The mine contains a toxic liquid explosive filling and detonates when pressure is applied to the body of the mine, for example when someone steps on, handles or otherwise disturbs it.[71] One variant of the PFM antipersonnel mine has a self-destruct mechanism that randomly detonates the mine up to 40 hours later.

Andrii Kovanyi, head of the Communications Department of the National Police of Ukraine in Khersonska region, told Human Rights Watch that Russian drones had been dropping PFM antipersonnel mines in the city. He said that police staff, including the head of demining operations, had been injured by the mines.[72]

Valeriy Sukhenko, who along with his wife was injured in a drone attack on their home in Antonivka in November, said drones began to emplace PFM antipersonnel mines in the area near their house in September.[73] He said sometimes the drones would drop plastic bags containing the mines, in a possible effort to disguise them and perhaps encourage people to pick them up. When the mines—green or brown in color—landed among leaves, they were difficult to spot. Sukhenko said Ukrainian deminers had stopped coming to the area because it had become unsafe and because Russian drones were targeting vehicles.

So, Sukhenko and his neighbor had taken it upon himself to destroy landmines they found using a long stick and gunfire.[74]

Ambulance medical worker Nastya, 46, said that on October 8, she and an ambulance driver responded to a call at the eastern edge of Antonivka, where a man had stepped on a mine.[75] Upon arriving at the location, Nastya saw that both of his legs had been partially traumatically amputated by the explosion. Three PFM antipersonnel mines lay around him. Nastya approached the man and placed a stretcher under him and applied tourniquets around his injured legs.

Human Rights Watch verified a drone video uploaded to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel on October 8 showing a drone recording the ambulance and the injured man lying on a soft stretcher.[76]

Nastya confirmed that the video shows the victim and incident described above.[77] Due to drone attacks and artillery shelling, Nastya said she was unable to continue to treat or evacuate the injured man. Nastya telephoned the ambulance call center to request that police or military evacuate the injured man. Nastya later learned that the injured man’s legs had been amputated above the knee.[78]

A video shared by Serhii Ivashchenko, 39, a community leader of Antonivka, shows a drone releasing five small munitions—which Ivashchenko says were PFM antipersonnel landmines—that land on a street in Antonivka.[79] The person filming was a resident who was taking cover at a bus stop and filmed the drone as it came to a stop and hovered above the street, releasing the munitions, which landed on the main road in Antonivka.

Human Rights Watch analyzed four photos and videos shared on Russian military-affiliated Telegram channels, which show PFM antipersonnel mines being fitted onto drones with a mechanism to drop these landmines. One video shows a drone being fitted with four PFM mines.[80] A comment with a picture underneath the post shows another container holding at least 27 PFM mines.[81] The PFM mines are packaged in twos or fours in a similar fashion to the mines shown being fitted onto the drone.

Human Rights Watch analyzed one drone video posted to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel on October 24 that shows a car driving out of Antonivka on the main road towards Sadove.[82] The drone follows the vehicle as it nears a set of train tracks. There are two small explosions one after the other on either side of the car that seem to originate from each wheel. The car veers off the main road and two more explosions occur on the right side of the vehicle. It is not clear if the driver was injured. The post is captioned: “Results of our Habr [the name of drone unit] operators, night mining...”

Researchers interviewed two residents from the towns of Sadove and Dniprovske, who were injured by emplaced PFM antipersonnel mines in November 2024.[83] In neither case could Human Rights Watch confirm whether the mines had been placed by drones or by other means.

Olena Seminikhina, 45, is a community leader of Sadove town, located approximately five kilometers east of Antonivka.[84] She said that on November 13, she and two colleagues left their office on foot to go help municipal workers who called her saying they had been injured in a drone attack. On the way, Seminikhina stepped on a PFM antipersonnel mine, sustaining a severe leg injury. She said she was taken to the O.S. Luchanskyi Kherson City Clinical Hospital in Kherson in a municipal car, where doctors amputated her leg. Later, her colleagues found three PFM antipersonnel mines at the location where she was injured. Seminikhina shared pictures of the landmines with researchers.

Serhii Dolhov, 50, is a tractor driver who lives in Dniprovske, a town located approximately eight kilometers west of Kherson.[85] On November 3, he was walking near his apartment building, when he stepped on a PFM antipersonnel mine that exploded. His left foot was almost completely severed by the blast and his right leg was injured by plastic fragments. Dolhov said, “I walked in this area a lot, so the mine must have appeared there maybe two or three days earlier. I am always looking up for drones, I wasn’t looking down for mines.”

The United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (HRMMU) shared information with Human Rights Watch about three civilians in Dniprovskyi and Antonivka injured by landmines between June and December 2024.[86] The HRMMU did not specify the type of mines or if they were dropped by drones.

Attacks on Health Care, Other Essential Goods and Services

The Russian drone attacks in Antonivka and Dniprovskyi have prevented or hindered residents from accessing essential goods and services including food and health care, medical and rescue services, as well as other services such as public transportation. Human Rights Watch analyzed 20 videos showing drones carrying out attacks of this nature in Antonivka and Dniprovskyi.[87]

Human Rights Watch interviewed medical and ambulance staff who said they had witnessed or responded to Russian drone attacks on ambulances, medical staff, and healthcare facilities in both Antonivka and Dniprovskyi. Staff told researchers that the attacks had severely affected people’s ability to access health care, including when wounded in Russian attacks.[88]

In two instances, Human Rights Watch corroborated witness accounts with Russian drone footage that showed drones targeting ambulances and killing and injuring ambulance personnel as they arrived at locations in response to civilian casualties from previous drone attacks.[89] The head of the Dniprovskyi District Council, Vladislav Kondratov, told researchers that the presence of Russian drones delayed emergency and medical staff responding to the impacts of attacks, sometimes for hours.[90]

Two residents told Human Rights Watch that in June 2024, drones began attacking grocery stores in Antonivka and Dniprovskyi, as well as vehicles delivering food and other goods to the stores.[91] Over the next few months, stores closed, forcing residents to travel further to procure basic goods and putting them at greater risk of being hit by drone attacks or artillery shelling.[92] In Antonivka, one resident told us the four or five stores in her area had all closed.[93] Human Rights Watch was able to corroborate witness accounts with video of one attack on a grocery store.[94]

The Kherson City Council Executive Committee told Human Rights Watch that Russian drone attacks have hit buses, injuring two drivers and damaging 22 vehicles.[95] The committee said some bus routes were regularly targeted by drones so buses at times ran less frequently.[96] Human Rights Watch analyzed five videos of five separate incidents of drones dropping munitions on buses in Antonivka and Dniprovskyi.[97]

Attacks on Health Care

Russian drones have been used to attack medical staff and property in Antonivka and Dniprovskyi on several occasions.[98] Human Rights Watch interviewed one staff member of the Kherson Regional Oncology Center and six ambulance personnel who had witnessed Russian drone attacks. In a letter to Human Rights Watch, Kherson’s City Council Executive Committee stated that Russian drone attacks had injured 21 medical staff in Kherson between May and December 2024.[99] Human Rights Watch could not confirm if those staff were injured in attacks that occurred when the medical personnel were on duty. Human Rights Watch analyzed seven videos showing Russian drone attacks on health care facilities, ambulances, and medical personnel.[100]

Mykola, a State Emergency Service of Ukraine (SESU) rescue worker, said:

We can’t safely respond to emergencies. When we get emergency calls, we contact the military to see if there are any drones in the area before we dispatch. Even if they give us the all-clear though, a drone can show up within five minutes of us arriving.101F101F[101]

Attacks on Ambulances

Human Rights Watch interviewed six ambulance personnel who had been victims of drone attacks while on duty and traveling in marked ambulance vehicles in five separate incidents that took place between August and October 2024. The attacks killed one ambulance doctor and injured eight ambulance personnel. In two incidents, researchers matched witness accounts with videos of drone attacks published to Russian military-affiliated Telegram channels. In three attacks, ambulance teams were responding to calls from civilians injured in previous drone attacks.[102]

In an incident on October 28 at 8 p.m., the team of ambulance driver Volodymyr Pavlyuk, 64, and a doctor and medical assistant, responded to a call from two people with leg injuries from a drone-dropped munition near the riverbank in Antonivka.[103] Upon arrival, Pavlyuk shone a flashlight to guide the doctor, Serhiy Kuchirenko, 64, and medical assistant Viktoria Zhogha, 40, to the victims lying on the ground about three meters from the ambulance and then went to retrieve the stretcher from the back of the ambulance.

Zhogha said she and Dr. Kuchirenko were by the open door on the right-hand side of the ambulance when she heard a drone.[104] She yelled out, “Drone! Drone!,” to try to warn the others. “I started calling the doctor and tried to hide, but I didn’t know where [to hide],” Zhogha said. “It was too dark. We were panicking. At the last second, I tried to enter the ambulance.” The explosion happened at that moment.

Pavlyuk found both Zhogha and Dr. Kuchirenko injured. “There was a puddle of blood around Serhiy [Dr. Kuchirenko] and he was silent,” Pavlyuk recalled. “He was sort of half sitting and half lying on the ground. Vika [Zhogha] had wounds to her leg.”[105] The blast wave gave Pavlyuk a concussion and significantly damaged his hearing.

Pavlyuk said the explosion damaged the front wheel, blew off the side mirror, and perforated the right side of the ambulance.[106]

Pavlyuk quickly put his colleagues both into the back of the ambulance together with one of the people injured in the attack the team had been responding to. He put the second injured civilian in the passenger seat. He sped away from the site, ignoring the punctured wheel to find a place under a tree to park and wait for another ambulance to come to their rescue. As the new team came and loaded the patients into their ambulance, Pavlyuk said, he could not tell if Dr. Kuchirenko was still alive. He was pronounced dead at the hospital.

“This is the worst incident I have ever experienced in my career,” Pavlyuk said. “It is the first time in my career that I went out on a call with a doctor and the doctor was killed while responding to the emergency.”[107]

Zhogha suffered fragmentation injuries to both legs, her right hip, and stomach. “When I have recovered, I would like to return [to work],” Zhogha said, about a month after the attack. “I love working, but time will tell.”[108]

Pavlyuk said that prior to this, he had not heard any outgoing fire by Ukrainian forces or seen any Ukrainian military in the immediate vicinity.

Human Rights Watch verified one drone video posted to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel that shows the attack that killed Dr. Kuchirenko and injured Zhogha and Pavlyuk. The video consists of two clips showing a drone filming with a thermal camera.[109] The first clip appears to show the attack that injured the two people Pavlyuk and his team were responding to. The clip starts with a drone flying and then hovering above a tree near some houses. After the drone drops a munition which detonates on the ground, a dog runs away, and the silhouette of a person can be seen lying on the ground. In the second clip, a drone is flying to the same location. As it arrives at the same location, the drone hovers over the ambulance. At least five people are moving around the area. Three individuals are positioned around the ambulance where Zhogha and Pavlyuk recounted they and Dr. Kuchirenko stood. A munition is visible falling toward the group of people for a few frames before an explosion occurs near the front right side of the vehicle.

Viacheslav Khlopov, a 46-year-old ambulance driver, said that on August 27, he, together with a doctor and a medical assistant, responded to an emergency call at about 5 p.m. to collect and transport two people injured in a drone attack in Antonivka.[110] When the ambulance approached the roundabout near Salut shopping center, Khlopov said he saw a drone start to follow it. As they approached the location they had been called to, the drone attacked the ambulance.

Human Rights Watch verified one drone video posted to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel on August 28 that shows the attack on Khlopov’s ambulance, 300 meters north of the roundabout.[111] The video begins with a drone following the ambulance. As the ambulance slows down, the drone drops a munition that lands in front of it. Shortly after, three people dash from the ambulance into a nearby building. Khlopov confirmed to researchers that this video shows the attack on him and his colleagues.[112]

Khlopov said he, the doctor, and the medical assistant all sustained concussions in the explosion.[113] The explosion severely damaged the bottom of the ambulance, all four tires, and the fuel tank. “If the explosion had hit the front of the car, we would all have been dead,” Khlopov said. The team called the police for backup, and the police evacuated them and the injured men they had been going to pick up to the hospital in their vehicle, as the ambulance was no longer useable.

Human Rights Watch verified a second video uploaded to the Ukraine Patrol Police’s Facebook page on August 28 showing police officers evacuating at least three individuals from the attack.[114] Two have been bandaged across the torso, while a third appears dressed in an ambulance staffer’s uniform and body armor.[115] Two verified photographs uploaded to a Ukrainian-language Telegram channel show three individuals in civilian clothing and beige body armor changing the tires of the ambulance.[116]

Ambulance driver Yuriy Ivannikov, 57, said that on August 3, he and his colleague responded to a call about a man injured in a drone attack in Antonivka.[117] When the team arrived at the location, the injured man pointed to the sky and said there were more drones. Ivannikov spotted a small black drone above. The injured man got into the ambulance and Ivannikov began driving away. As they pulled onto the main road in Antonivka, two other people also injured in another drone attack shouted out for help. Ivannikov stopped the ambulance and let them jump in. At that moment, he said a munition exploded near the ambulance, shattering all the windows. Ivannikov quickly drove away. Ivannikov and his colleague both sustained concussions as a result of the attack.[118]

On October 21 at around 9 p.m., ambulance assistant Yevgen Selivanov, 46, and his team were responding to a stroke victim in an apartment building in Dniprovskyi District. As Selivanov and two medical assistants walked towards the entrance of the building, a drone dropped a munition, injuring all three of them. Selivanov did not see or hear the drone prior to the attack. Later at the hospital, the doctor treating Selivanov removed a small round metal fragment from his shoe and explained that it was typical of drone attacks.

Unrelated to this incident, researchers spoke to a surgeon at Luchansky Hospital in Dniprovskyi District, who described similarly shaped metal fragments he said he found in drone attack injuries.[119] Human Rights Watch analyzed three photographs posted to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel showing scrap metal fragments wrapped around a small explosive charge, which appear to correspond with the fragments described by Selivanov and the surgeon.[120]

Attacks on the Kherson Regional Oncology Center

Director Iryna Sokur of the Kherson Regional Oncology Center, a hospital in Antonivka, said drones started attacking the hospital and its grounds in July 2024, using explosive weapons.[121] Sokur said the drones initially targeted the cars of patients who parked outside the hospital. Some patients arriving for treatment were injured in these attacks, and the hospital set up an emergency surgical room on the first floor to treat them.[122] Drone attacks also injured a nurse who worked at the hospital. She suffered a concussion and fragmentation injuries when a drone dropped a munition near the entrance.[123]

Sokur said businesses supplying the hospital with medical equipment, medication, and food suspended deliveries when drones started attacking vehicles in Antonivka.[124] The hospital began using its two cars to drive to the north of Kherson to pick up supplies and transport them back to the hospital.

Sokur said drones also dropped munitions that damaged two large generators that powered the facility after the neighborhood lost electricity. Human Rights Watch analyzed two drone videos uploaded to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel on August 15 showing two attacks on generators at the Oncology Center. In both videos, a drone hovers above a generator for several seconds before dropping a munition.[125]

Artem, 27, a driver and guard working at the center, described two separate attacks in which his two personal cars were damaged.[126] On the night of November 19, Artem was in the oncology center’s basement when he heard a big explosion. When he went out the next morning, he found that a quadcopter drone had hit his car, which was parked directly outside the hospital. Artem said he found the remnants of the drone engine inside his car. That same morning, a drone dropped a munition on and damaged his second car, which he had also parked outside the hospital, Artem said. He shared with researchers pictures he took of the vehicles after the attack which showed hexagonal incendiary capsules from 122mm Grad incendiary rockets. Human Rights Watch verified one video uploaded to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel on November 20 that shows a drone hitting a parked vehicle at the center.[127] Artem confirmed with researchers that this video shows the attack on his car.[128] Artem said he knew of no Ukrainian military in the area and had not heard outgoing fire immediately prior to the attack.