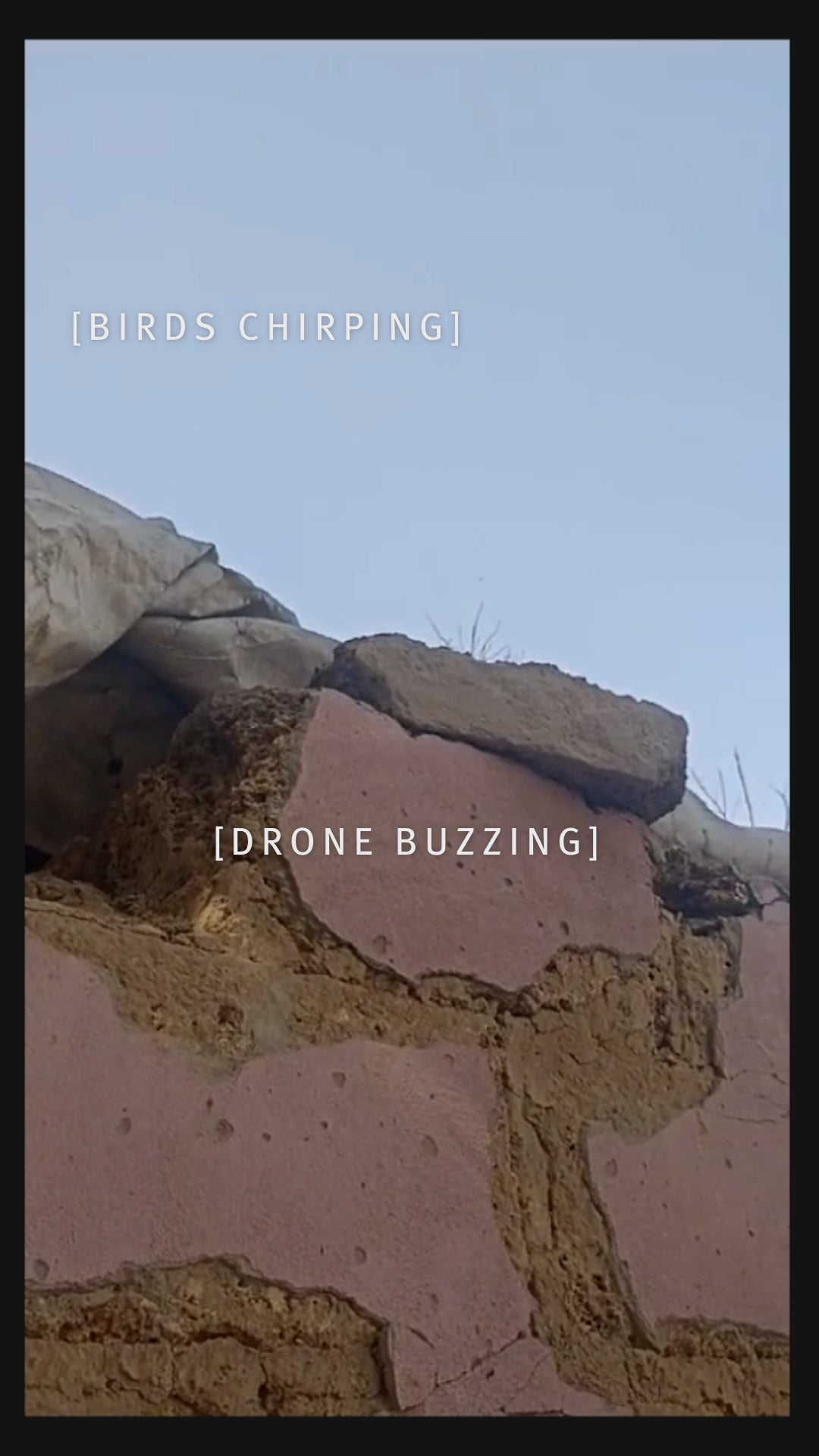

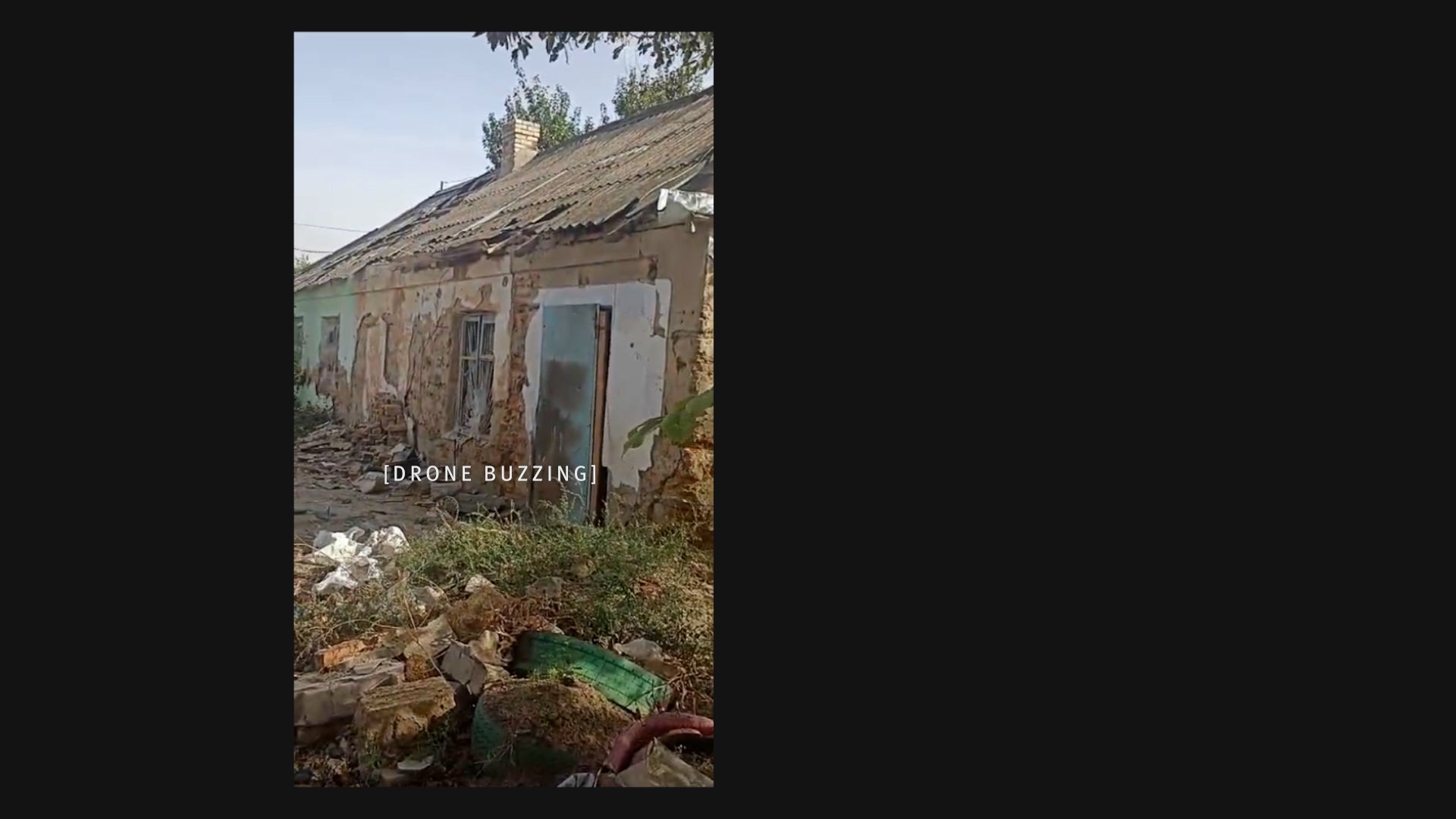

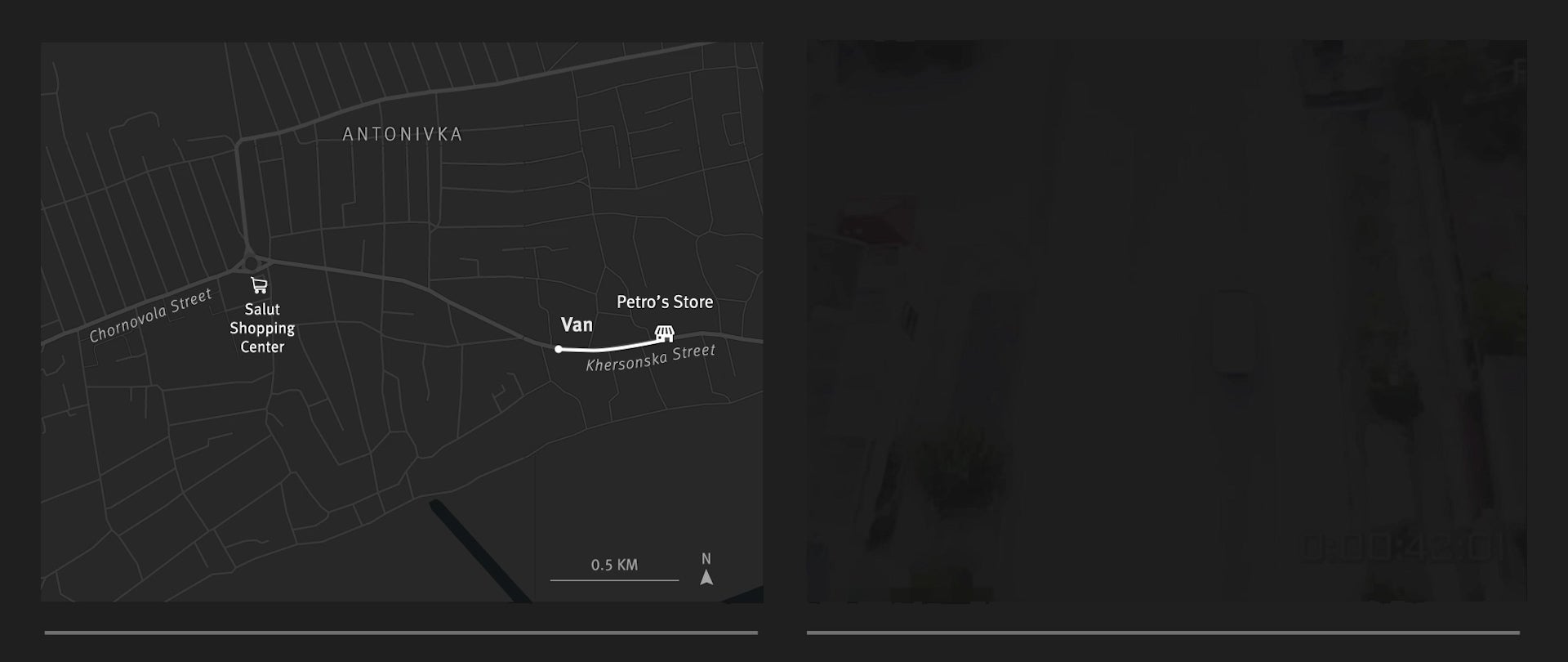

On a late summer day, Serhii is walking in Antonivka, a suburb of Kherson, Ukraine. Around him are war-damaged homes.

Suddenly, he hears a buzzing noise.

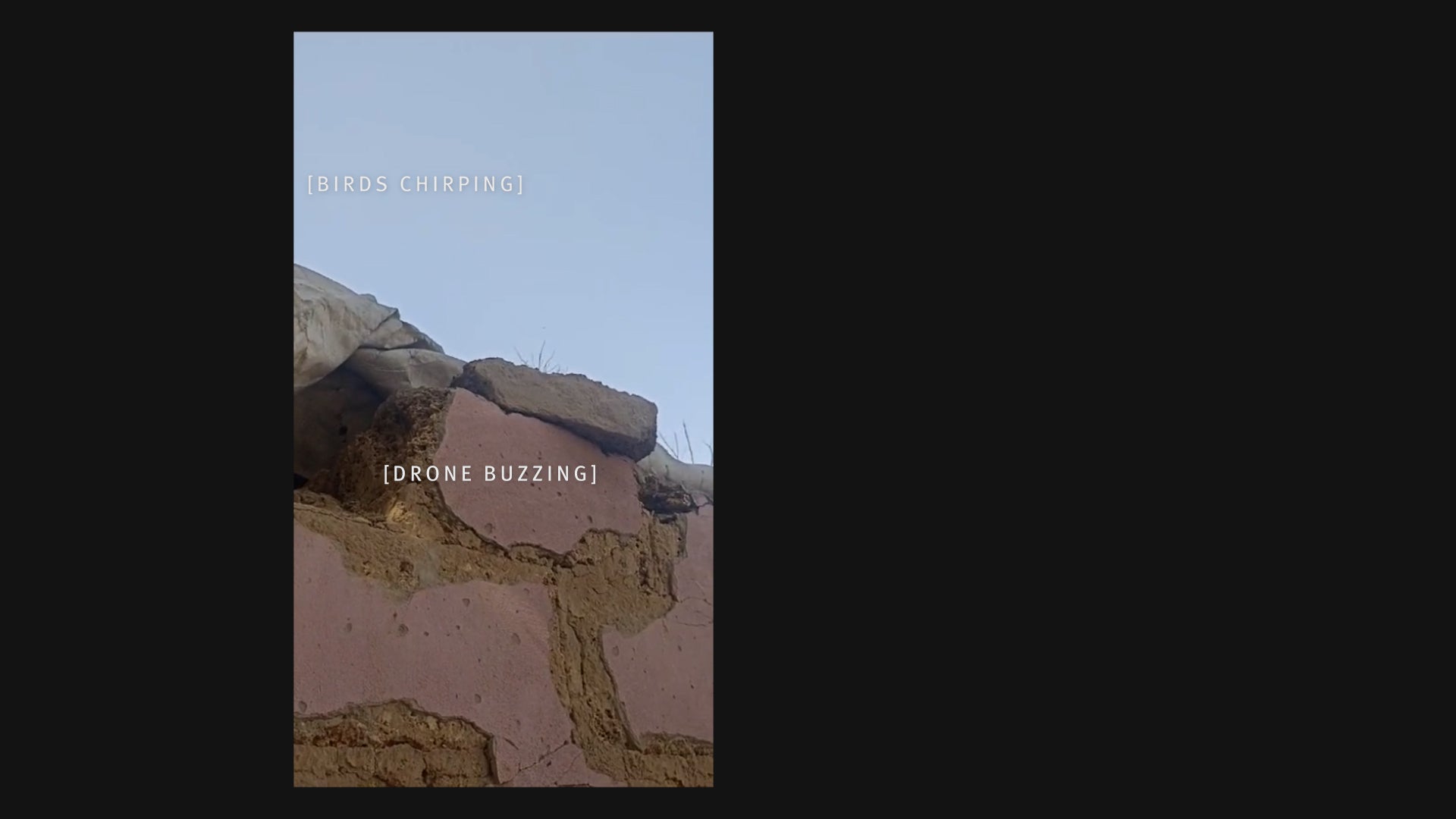

Serhii takes cover behind a wall and beneath a tree. For residents of Kherson, this sound means danger.

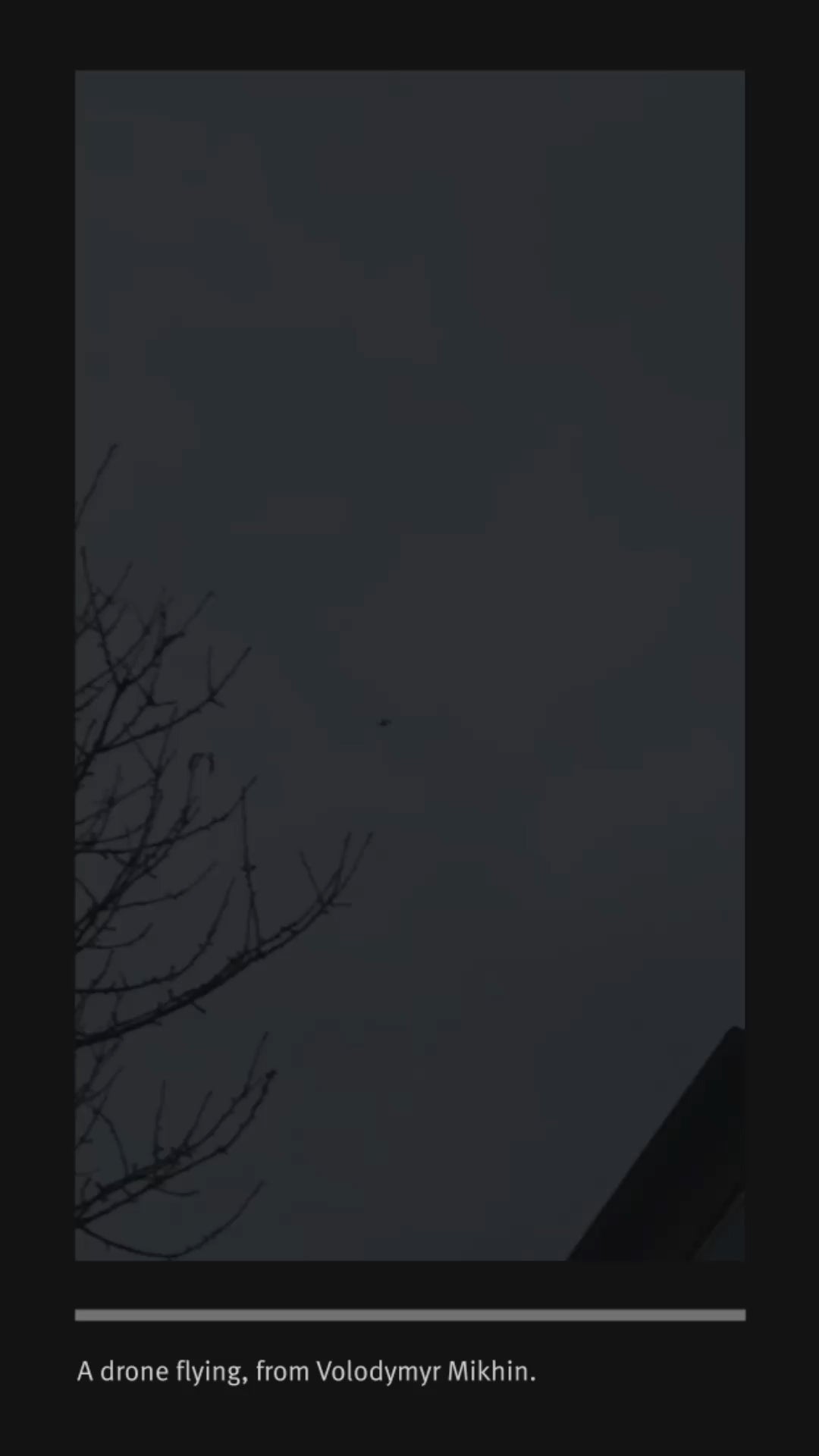

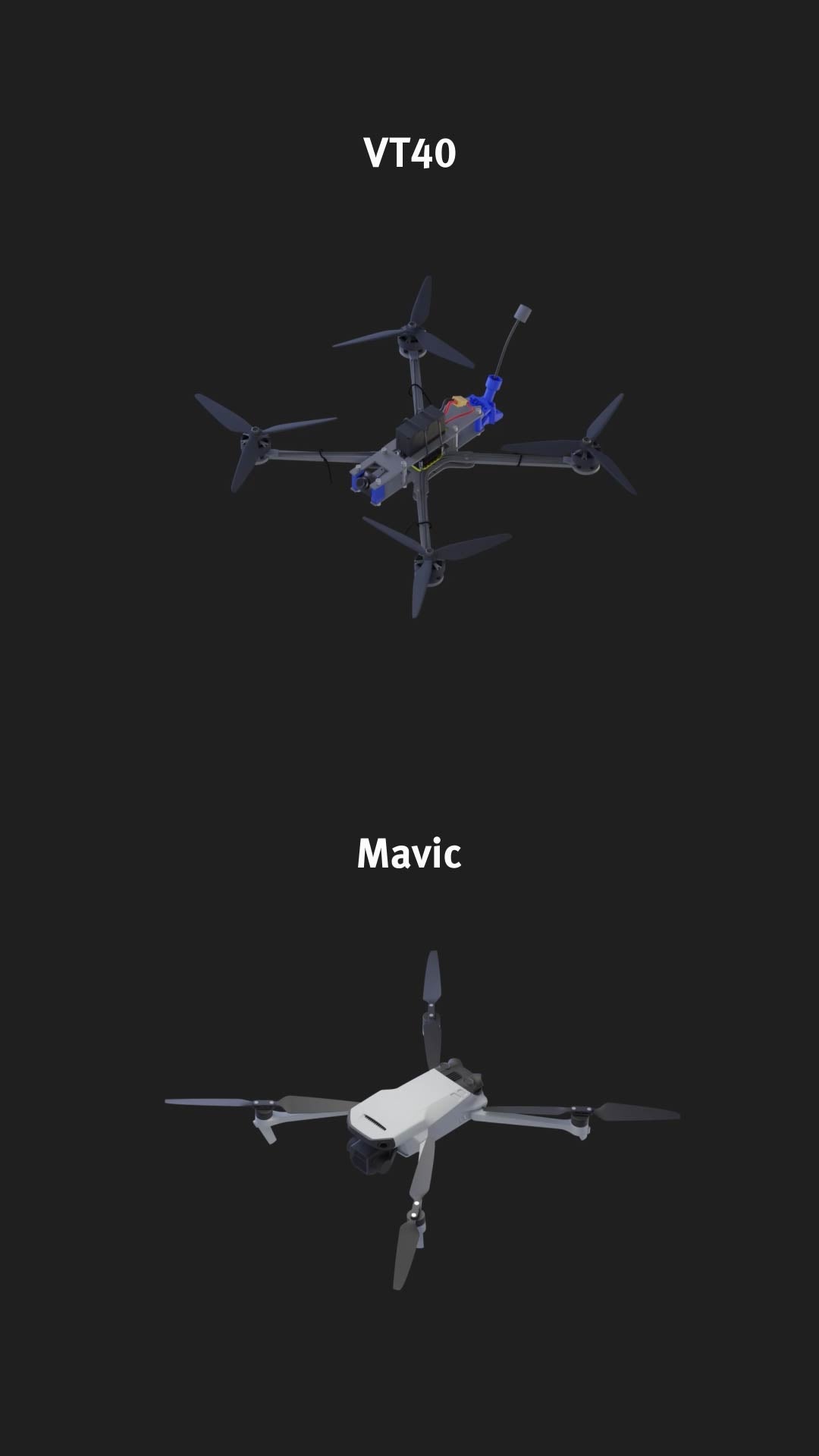

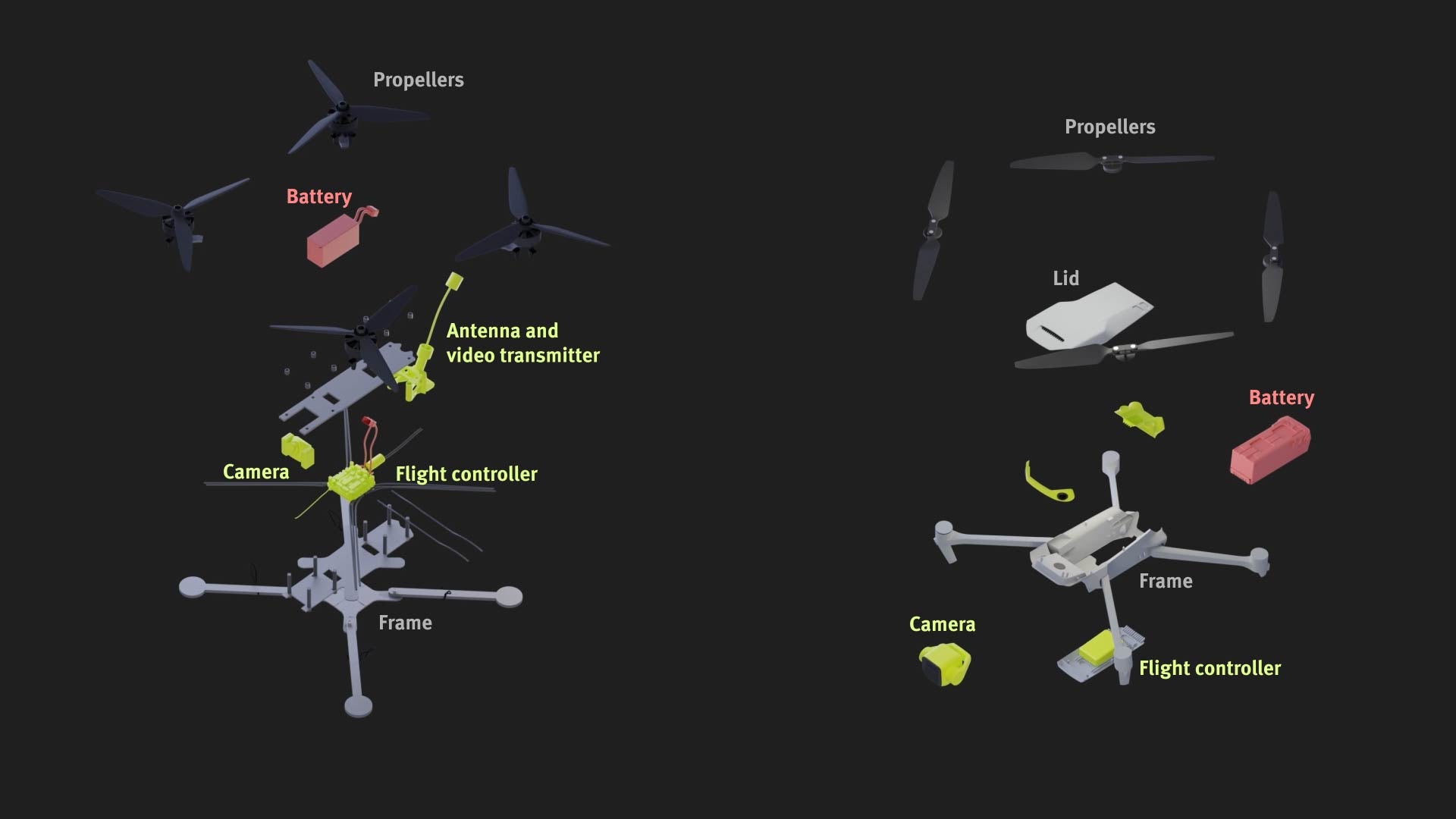

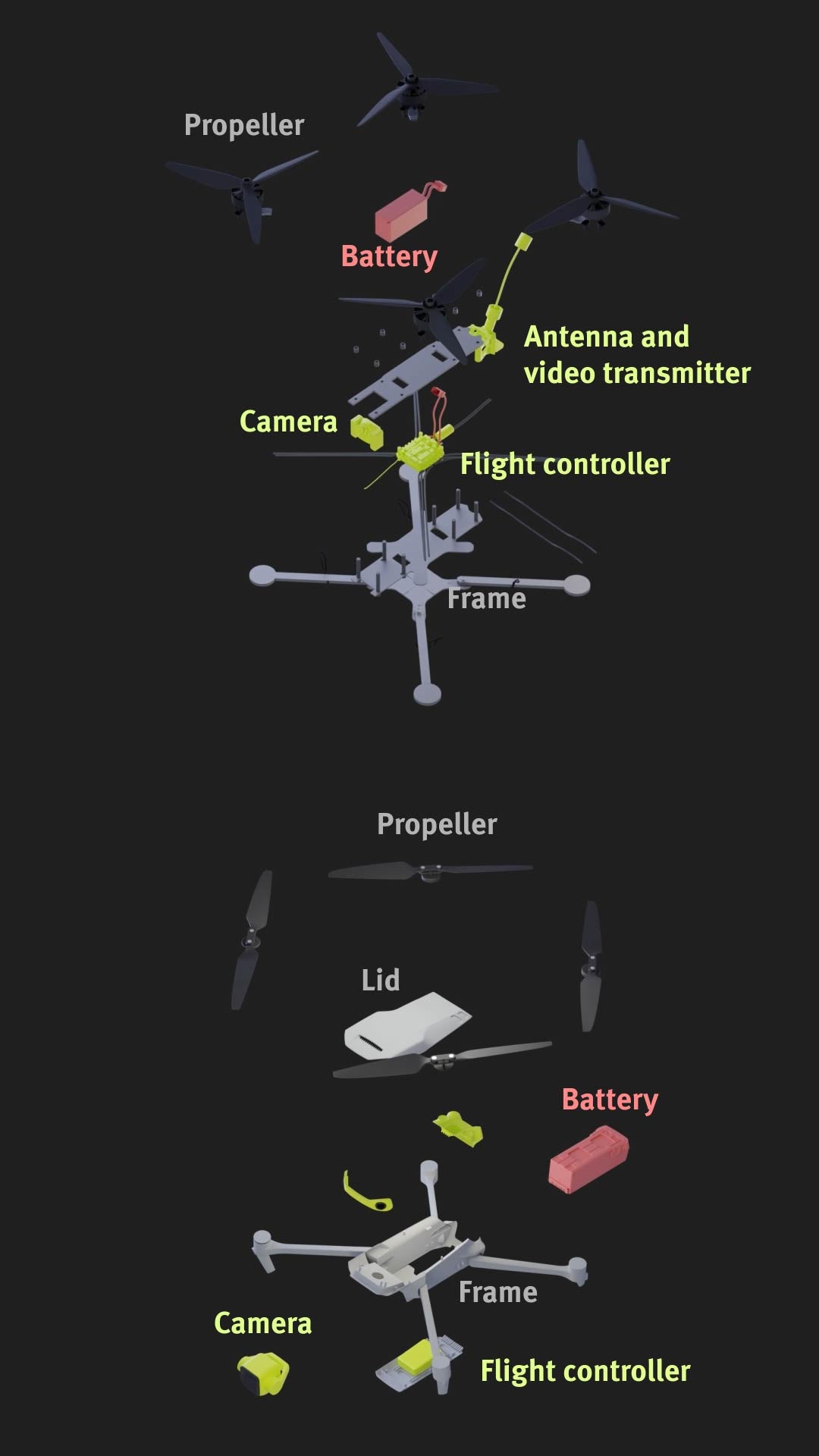

Using his phone to film through the branches, he spots a drone flying above him.

Moments later, an explosion rips through the air, shaking Serhii.

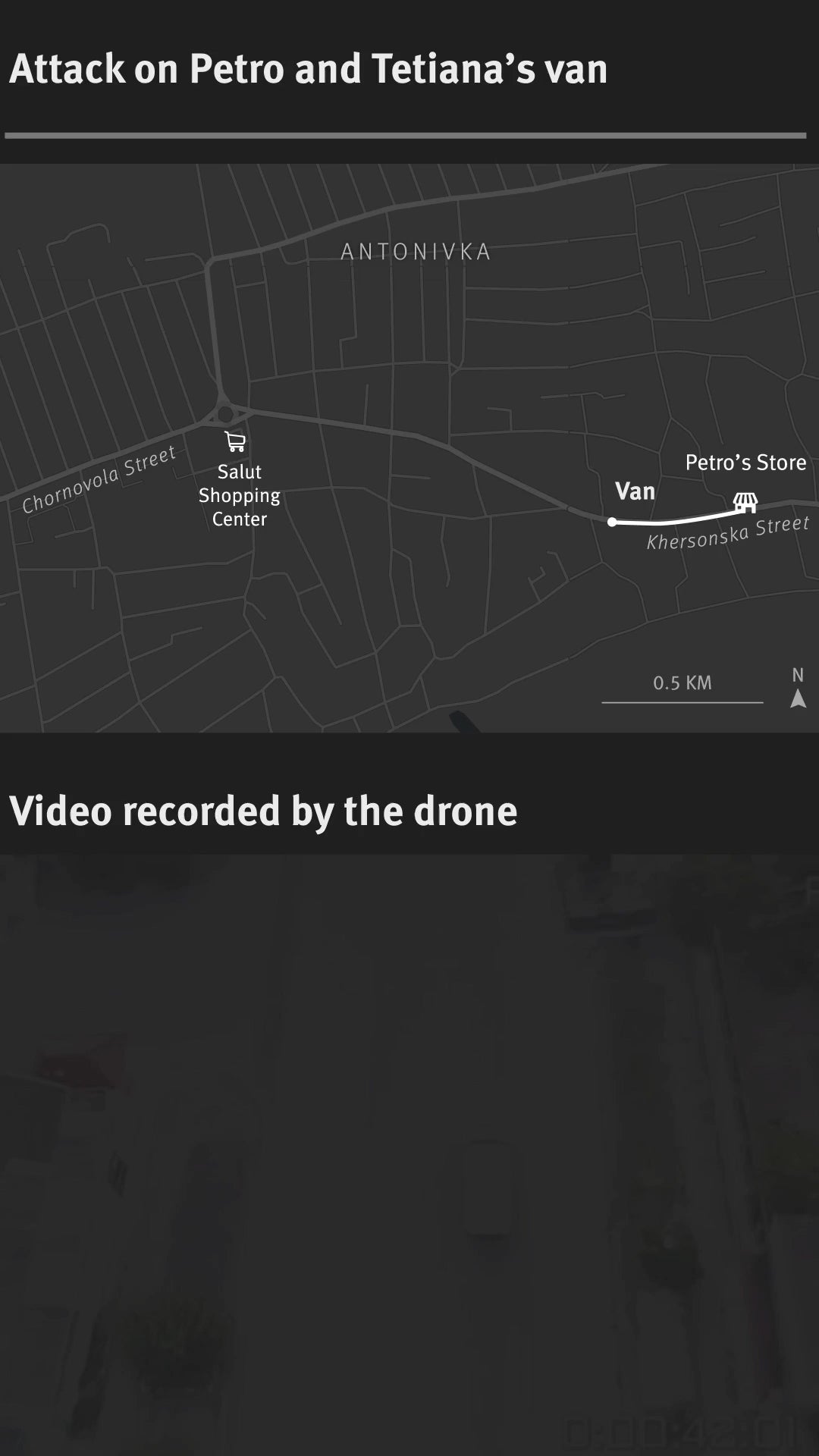

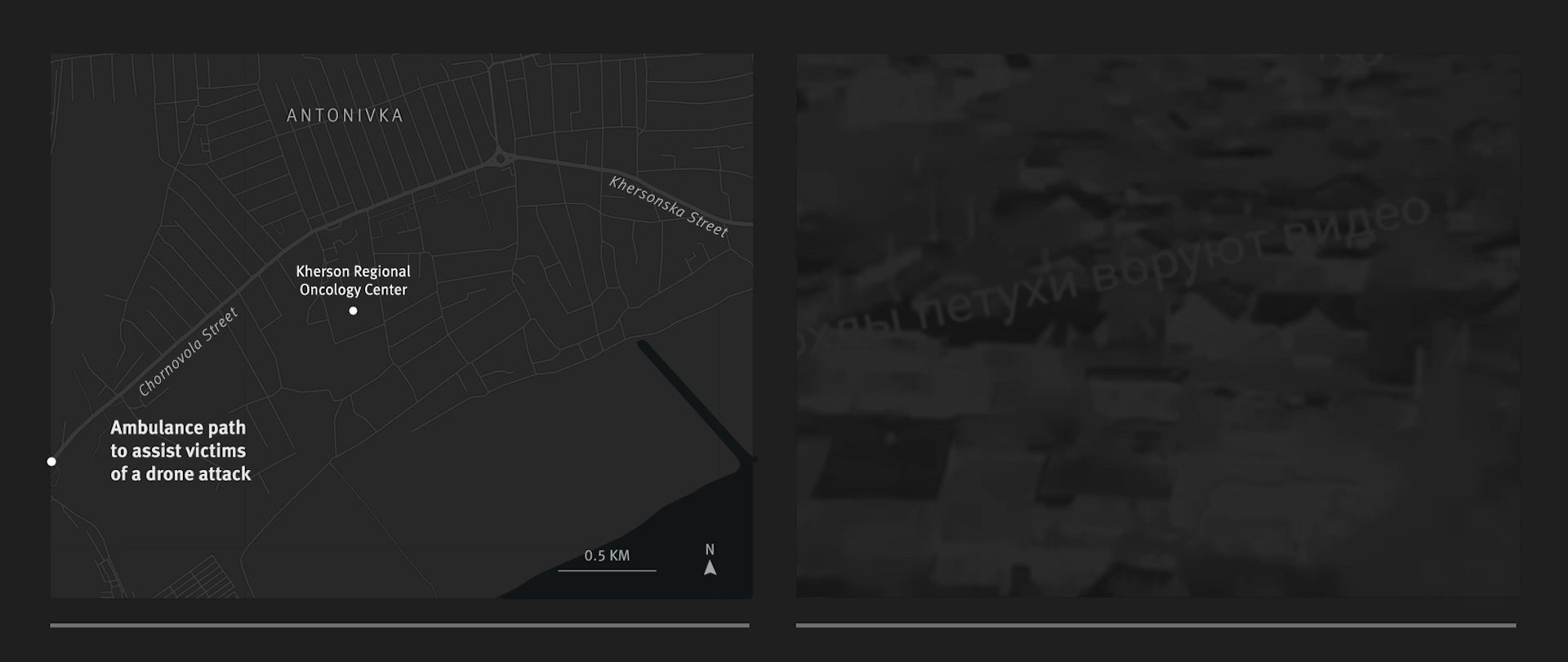

He rushes over to the site of the explosion, swearing when he sees three injured people at a bus stop: two women, one of them pregnant, and a man who was bleeding heavily from his head.

Serhii later told Human Rights Watch that he helped the three injured people reach a hospital.

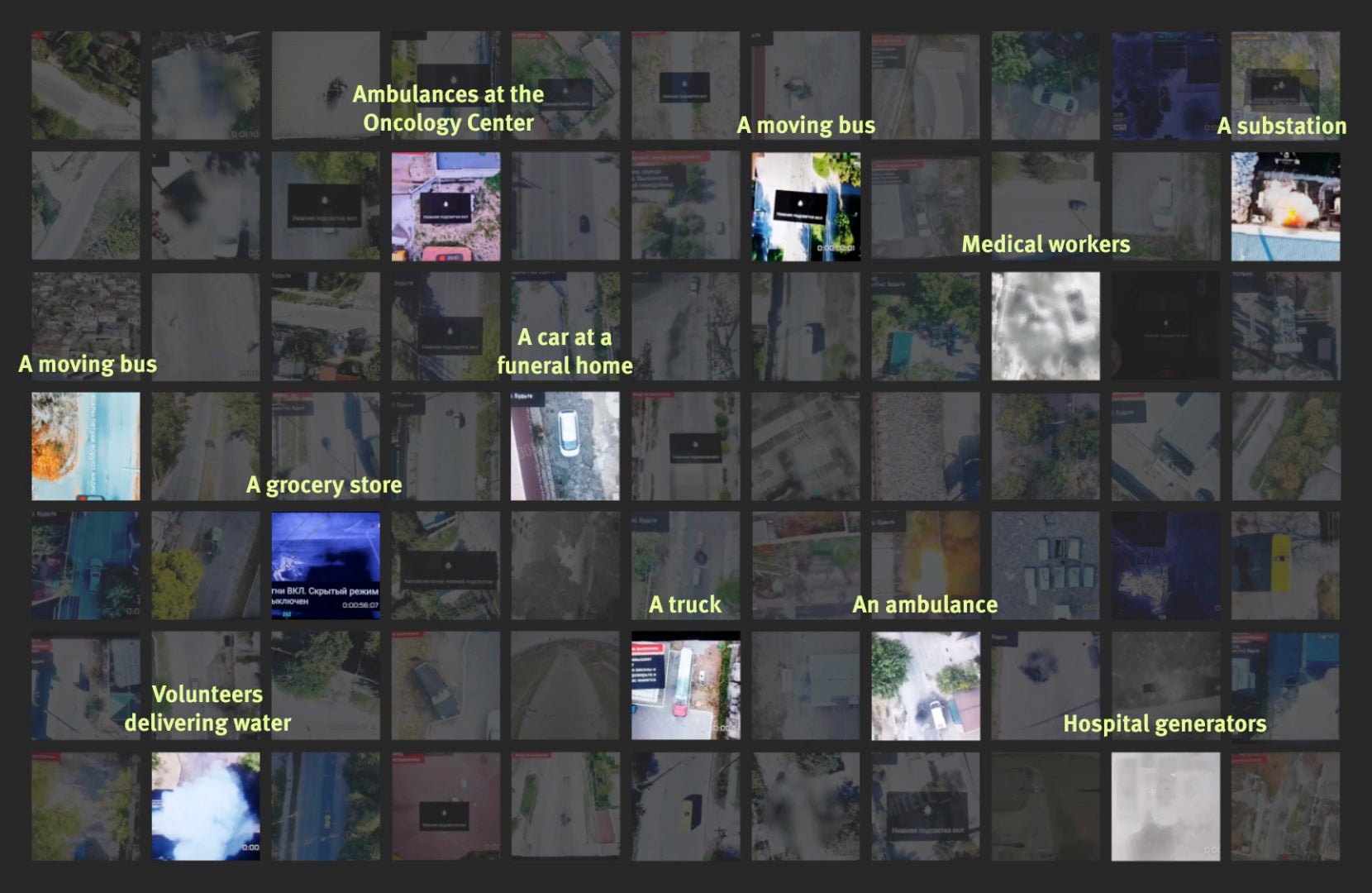

Many other residents have recorded videos of drones flying above and dropping explosive weapons.

Russian military drone operators have uploaded video recordings of many of these attacks to social media.

Human Rights Watch analyzed 83 videos showing Russian drone attacks in Kherson and interviewed dozens of victims and witnesses of attacks on residents, their homes, civilian vehicles, ambulances, and other civilian objects.

In some cases, researchers were able to match videos of drone attacks to witness testimony recounting those events.

The intentional targeted killing of civilians is a serious violation of international humanitarian law and a war crime. Our research found that Russian forces have committed war crimes and crimes against humanity through their use of drones to target civilians and civilian property and infrastructure in Kherson since June 2024.