Summary

In late August and September 2017, Bangladesh welcomed the sudden influx of several hundred thousand Rohingya refugees fleeing ethnic cleansing in Myanmar. This followed an earlier wave of violence in October 2016, which forced over 80,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. Bangladesh’s respect for the principle of nonrefoulement is especially praiseworthy at a time when many other countries are building walls, pushing asylum seekers back at borders, and deporting people without adequately considering their protection claims. Currently, more than 900,000 Rohingya refugees are in the Cox’s Bazar area in Bangladesh’s southern tip. These consist of nearly 700,000 new arrivals on top of more than 200,000 Rohingya refugees already living in the area, having fled previous waves of persecution and repression in Myanmar. Bangladesh has continued to let in another 11,432 since the beginning of 2018 through the end of June 2018.

While the burdens of dealing with this mass influx have mostly fallen on Bangladesh, responsibility for the crisis lies with Myanmar. The Myanmar military’s large-scale campaign of killings, rape, arson, and other abuses amounting to crimes against humanity caused the humanitarian crisis in Bangladesh. And Myanmar’s failure to take any meaningful actions to address either recent atrocities against the Rohingya or the decades-long discrimination and repression against the population is at the root of delays in refugee repatriation. Bangladesh’s handling of the refugee situation needs to be understood in the context of Myanmar’s responsibility for the crisis.

The Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp near the town of Cox’s Bazar, sometimes referred to as the “mega camp,” is now the world’s largest refugee camp. It was built quickly and haphazardly on a hilly jungle. “Our entire village came together and settled on this spot,” said Amanat Shah, 19, who arrived on September 2, 2017. “At first this was a jungle, but we cleared it. Now there are no trees.” His hut now sits on a densely packed, steep slope with almost no vegetation to keep the clay-sand mix under him from eroding or suddenly sliding away.

The imminent threat for Rohingya refugees is the likelihood that the Cox’s Bazar area will be hit by a cyclone or comparable high winds and storm-surge flooding. Throughout the Human Rights Watch May 2018 visit, refugees were busily shoring up their huts, construction crews were working to build safer locations to accommodate people, and first responders were conducting drills to mitigate disaster. Notwithstanding these efforts, the camps and their residents remain highly vulnerable to catastrophic weather events.

As of June 10, 2018, about 215,000 refugees in the Cox’s Bazar area were at risk of landslides and flooding, with 42,000 at highest risk, but only 19,500 had been relocated from highest risk locations, as of July 4. Evacuation plans in the event of a cyclone or other serious weather event were stymied by the government’s movement restrictions on the refugees and a lack of stable structures in which to evacuate people.

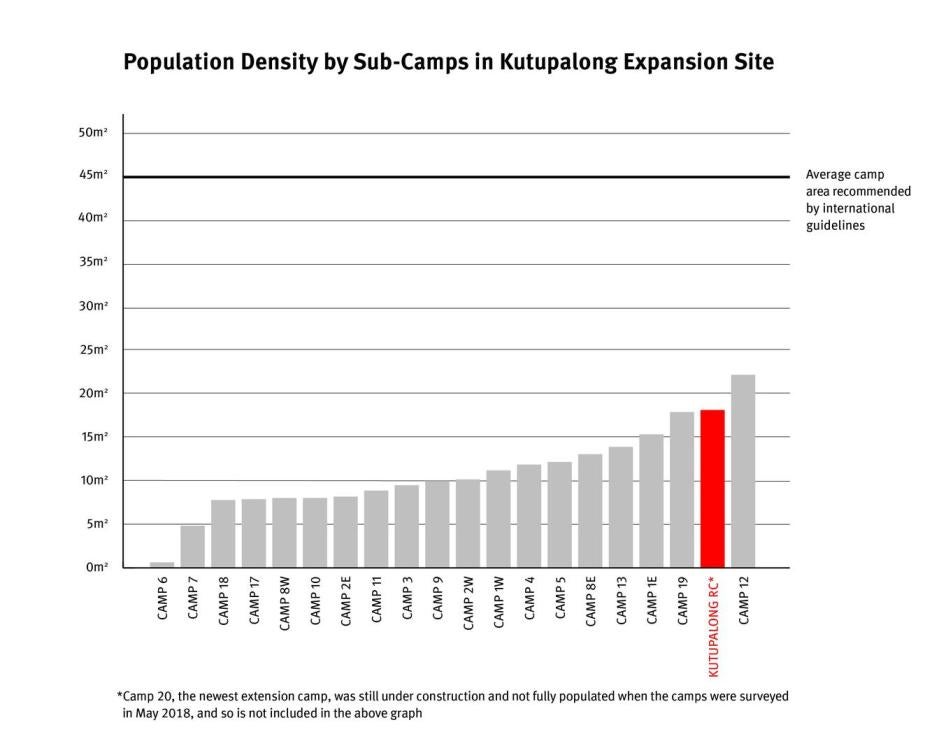

The mega camp is severely overcrowded. The average usable space per person is 10.7 square meters per person, whereas the recommended international standard for refugee camps is 45 square meters per person. Densely packed refugees are at heightened risk of communicable diseases, fires, community tensions, and domestic and sexual violence.

The Rohingyas’ identity as Myanmar nationals motivates their preference for repatriation so long as they are granted citizenship, provided security, and recognized as Rohingya. Both this and their reluctance to criticize their hosts has also made them hesitant to make demands on Bangladesh to improve their current living conditions. “Bangladesh is not my country,” said Kadir Ahmed, age 24. “I want to go back to our land. If the Myanmar government had not killed and tortured us, we would not have left.”

For a variety of reasons, including avoiding having refugees be an issue in upcoming national elections in late 2018, the Bangladeshi central government does not want to acknowledge publicly that the Rohingya refugees will not be repatriating anytime soon—and their stay could be prolonged. The authorities have resisted any efforts by international humanitarian and development agencies or by the refugees themselves to create any structures, infrastructure, or policies that suggest permanency.

As a result, refugee children do not go to school, but rather to “temporary learning centers,” where “facilitators,” not “teachers,” preside over the classrooms. The learning centers are inadequate, only providing about two hours of instruction a day. Most classes are geared toward the pre-primary and early grades of primary school, and there are basically no educational offerings for adolescents or adults. Only one-quarter of school-aged children attend temporary learning centers, which means nearly 400,000 children and youth are not receiving a formal education.

Relocation elsewhere in Bangladesh to a location with fewer environmental risks and adequate standards of services is crucial for the health and well-being of the Rohingya refugees. However, this needs to be done with consultation and consent of the refugees to keep their displaced village communities intact and maintain contact with the broader Rohingya refugee community.

The Bangladesh navy and Chinese construction crews have prepared the as yet uninhabited island of Bhasan Char for the transfer of 100,000 refugees from the Cox’s Bazar area, and Bangladesh has indicated that transfers to the island will begin in September. However, the flat, mangrove and grass island, formed only in the last 20 years by silt from Bangladesh’s Meghna River, does not appear to be suitable for the accommodation of refugees. Experts predict that Bhasan Char could become completely submerged in the event of a strong cyclone during a high tide. In addition to Bhasan Char’s environmental failings, housing refugees there would unnecessarily isolate them, and if they were not allowed to leave, it would essentially become an island detention center.

Bhasan Char does not appear to be a suitable relocation site for refugees for a host of reasons: 1) it is not sustainable for human habitation; 2) it could be seriously affected by rising sea levels and storm surges; 3) it likely would have very limited education and health services; 4) it would provide extremely limited opportunities for livelihoods or self-sufficiency; 5) it would unnecessarily isolate refugees; 6) the Bangladeshi government has made no commitment to allow refugees’ freedom of movement in and from Bhasan Char; 7) it is far from the Myanmar border; and 8) the refugees have not consented to move there.

The Rohingya refugees who spoke to Human Rights Watch expressed gratitude to the people and government of Bangladesh. That goodwill could be squandered, however, if government security forces pressure refugees to go to Bhasan Char, putting their lives in danger.

Bhasan Char is not the only relocation option. There are six feasible relocation sites in Ukhiya subdistrict totaling more than 1,300 acres that could accommodate 263,000 people. These sites are situated in an eight kilometer stretch due west of the Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp between the mega camp and the coast. As such, these sites are within the containment area the government has designated to limit free movement of refugees.

Another challenge facing Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh is the lack of recognized legal status, which puts them on precarious legal footing under domestic law. All the new arrivals are officially registered as “Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals,” a designation that denies their refugee status and any rights attached to that status. This makes them more vulnerable to denial of freedom of movement, access to public services, education, and livelihoods, as well as to arrest and exploitation. However, as a party to core international human rights treaties, Bangladesh is nevertheless obligated to ensure all persons within its jurisdiction, including refugees, retain access to fundamental rights.

The refugees interviewed privately by Human Rights Watch all expressed their preference to go back to Myanmar, but only when conditions allowed them to return voluntarily: citizenship, recognition of their Rohingya identity, justice for crimes committed against them, return of homes and property, and assurances of security, peace and respect for rights.

“Creating a conducive environment for return rests with Myanmar, not here,” Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar-based refugee relief and repatriation commissioner, Abul Kalam, told Human Rights Watch. “We cannot force them back.”

Although not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, Bangladesh has upheld its customary international law obligation to keep the border open to fleeing Rohingya refugees and acted to accommodate and meet the humanitarian needs of hundreds of thousands of desperate refugees fleeing crimes against humanity. More than nine months since the crisis began, it remains an emergency situation, one not likely to be resolved anytime soon.

Human Rights Watch calls on the government of Bangladesh to establish readily accessible, hard-structured cyclone shelters to enable evacuation of refugees in Kutupalong-Balukhali mega camp to safer areas. The authorities should relocate refugees from the mega camp to smaller, less densely packed camps on flat, accessible land in Ukhiya subdistrict. It should immediately terminate plans to relocate Rohingya refugees to Bhasan Char unless and until independent experts determine that it is suitable for the accommodation of refugees, and until the government ensures that refugees who consent to relocate there will be allowed freedom of movement on and off the island. Bangladesh should register the Rohingya who have fled Myanmar as refugees, ensure access to adequate health care and education, and enable greater freedom of movement to engage in livelihood activities outside the camp.

The Myanmar government bears responsibility for the Rohingya refugee crisis and resolving it will necessitate fundamental and durable changes in Myanmar. The government will need to ensure full respect for returnees' human rights, equal access to nationality, and security among communities in Rakhine State as a precondition for voluntary repatriation in safety and dignity.

In the meantime, donor governments and inter-governmental organizations should be genuinely and robustly involved, both in supporting Bangladesh to meet the humanitarian needs of all Rohingya refugees – particularly by funding the humanitarian appeal for the Rohingya humanitarian crisis – but also by applying concerted and persistent pressure on Myanmar to meet all conditions necessary for safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya refugees.

Recommendations

To the Government of Bangladesh

- Provide Rohingya refugees with legal status and documentation that recognizes their status as refugees.

- Provide all children access to free and adequate education.

- Respect the rights of refugees to freedom of movement and to a livelihood.

- Take all feasible steps to ensure that humanitarian standards for Rohingya refugees, including population density for refugee camps, are consistent with those enumerated in the Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response (SPHERE standards).

- Make available an additional 1,500 acres of flat, accessible land in Ukhiya subdistrict to decongest the Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp.

- Relocate more than 200,000 refugees who are most at risk from landslides and flooding to smaller, less densely packed camps.

- Allow the construction of readily accessible, hard-structured cyclone shelters to enable evacuation of refugees in Kutupalong-Balukhali in the event of storm surges.

- Terminate plans to relocate Rohingya refugees to Bhasan Char unless and until independent experts determine that it is suitable for the accommodation of refugees, and until the government ensures that refugees who consent to relocate there will be allowed freedom of movement on and off the island.

- Encourage and facilitate democratic governance structures within the camps that promote refugee consultation on services, relocation, repatriation, relief, and development and that give voice to women, people with disabilities, and other marginalized groups.

- Engage refugees in environmental conservation, climate-mitigation activities, and infrastructure development that will benefit both the refugees and local host communities.

- Ensure access to basic services for persons with disabilities, including equal access to food and non-food distributions, adequate medical care, including mental health care, counseling and psychosocial support; help children with disabilities access education.

- Ensure persons with disabilities, including those with newly acquired disabilities due to the attacks in their home country, are explicitly identified as a high-risk population.

- Continue to facilitate the work of international humanitarian and development organizations by avoiding onerous visa restrictions, project approvals, and other bureaucratic barriers.

- Give UNHCR lead responsibility for coordinating the humanitarian response to the Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh.

- Ratify the 1951 Refugee Convention, its 1967 Protocol, and the 1954 and 1961 Statelessness Conventions and enact legislation to implement them.

- To allow outside scrutiny and generate trust among the refugee population, publish the memoranda of understanding (MOU) concerning data sharing and repatriation of Rohingya refugees signed with the government of Bangladesh and UNHCR.

To the Government of Myanmar

- Respect the right of return for Rohingya refugees who have been arbitrarily or unlawfully deprived of their former homes, lands, properties or places of habitual residence; they have the right to return to their place of residence or of choice and to the return of their property. Those unable or unwilling to return to their homes have the right to choose compensation from the government for the loss of all their homes and properties. Refugees who have been arbitrarily or unlawfully deprived of their liberty, livelihoods, citizenship, family life, and identity also have the right to restitution.

- Ensure that refugees freely seeking to return are verified in a fair and timely manner, and facilitate their return in a fair, safe, and orderly manner in cooperation with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and other relevant parties.

- Ensure full respect for returnees' human rights, equal access to nationality, and security among communities in Rakhine State as a precondition for voluntary repatriation in safety and dignity.

- Allow unfettered access in Rakhine State for UNHCR and other humanitarian agencies, the media, diplomats, and rights observers, including to monitor the security of any returnees.

- Close all internally displaced persons (IDPs) camps in Rakhine State in an orderly manner and, in cooperation with international partners, provide transitional security to enable voluntary returns in safety and dignity to places of origin or alternative locations chosen by the IDPs, while ensuring that returnees have access to services and livelihoods.

- As recommended by the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, ensure freedom of movement for all people in Rakhine State irrespective of religion, ethnicity, or citizenship status, and that all communities have equal access to education, health, livelihood opportunities, and basic services.

- Rescind the 1982 Citizenship Law or amend it in line with international standards: ensure the law is not inherently discriminatory, eliminate distinctions between different types of citizens, and use objective criteria to determine citizenship, such as descent, through which citizenship is passed through one parent who is a citizen or permanent resident.

- In accordance with the Convention on the Rights of the Child, revise the Citizenship Law to ensure that Rohingya children have the right to acquire a nationality where otherwise they would be stateless because they have no relevant links to another state. Until the Citizenship Law is rescinded or amended, interpret it, to the extent possible, in accordance with international obligations and standards on non-discrimination.

- To allow outside scrutiny and generate trust among the refugee population, publish the memorandum of understanding (MOU) concerning the repatriation of Rohingya refugees signed by UNHCR together with UNDP and the government of Myanmar.

To Humanitarian Agencies

- Refer to the Rohingya in Bangladesh as “refugees” to ensure they receive full refugee protections.

- Ensure that humanitarian standards for Rohingya refugees are consistent with those enumerated in the SPHERE standards.

- Urge the Bangladeshi government to give UNHCR lead responsibility for coordinating the humanitarian response to the Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh.

- Incorporate protection measures, targeted services, and staff training into all humanitarian assistance projects to meet the particular needs of refugees at risk, such as unaccompanied children, families traveling with young children, victims of human trafficking, people who have suffered or are at risk of gender-based violence (forced marriage, domestic abuse, etc.), women traveling on their own and female heads of household, pregnant and lactating mothers, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people, older people, and persons with disabilities.

- Install lighting throughout camps, and especially in the areas of latrines and wash blocks, to mitigate sexual and gender-based violence and other harassment and criminality at night.

- Ensure toilet and bathing facilities in camps are accessible for people with disabilities and adapted so they can use them while ensuring privacy and dignity.

- Ensure alternative means of distribution and delivery of food for people with disabilities and other groups such as older people.

- Advocate and work to establish and implement psycho-social support programs for refugees with mental health needs.

To the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- Implement the above recommendations to humanitarian agencies generally.

- To allow outside scrutiny and generate trust among the refugee population, publish the two memoranda of understanding (MOU) concerning data sharing and repatriation of Rohingya refugees signed with the government of Bangladesh, and the MOU on repatriation that UNHCR and UNDP signed with Myanmar.

- If repatriation operations commence, provide refugees with complete, objective, up-to-date and accurate information about conditions in prospective areas of return, including security conditions, and availability of assistance and protection to reintegrate in Myanmar. Do not promote or facilitate any “voluntary repatriation” operation that does not give refugees a genuine choice between staying or returning.

- Together with government authorities and other humanitarian agencies, including the International Organization for Migration, work to replace the majhi system of block leaders in the camp with democratic governance structures to ensure proper consultation and representation of refugee wishes and complaints, as well as to reduce corruption and entrenched power structures that marginalize women and other groups.

To Donor Governments

- Promptly provide assistance to help meet the needs of the Rohingya refugee population as outlined in the Joint Response Plan (JRP).

- Call on the Bangladeshi government to give UNHCR lead responsibility for coordinating the humanitarian response to the Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh.

- Work with the Bangladeshi government, UN agencies, and NGOs to ensure that humanitarian standards for Rohingya refugees are consistent with those enumerated in the SPHERE standards.

- Oppose the relocation of Rohingya refugees to Bhasan Char and do not fund projects to develop the island as a refugee relocation site.

- Promote the right of return for Rohingya refugees, but simultaneously insist on respect for the principle of nonrefoulement and that any repatriation of Rohingya refugees is based on fully informed consent, in accordance with international standards, and monitored and facilitated by UNHCR.

- While recognizing the limits of third country resettlement, offer to resettle refugees from Bangladesh who are at specific risk or have relatives living in third countries who petition for family reunification.

- Pressure the government of Myanmar to meet all conditions listed in the recommendations above that are necessary for voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of Rohingya refugees.

- Urge the Security Council to refer the situation in Myanmar to the International Criminal Court.

- Ensure implementing partners include people with disabilities in their humanitarian programming.

- When providing new funding for infrastructure, stress that the infrastructure should be accessible for persons with disabilities and not create additional barriers to the participation of persons with disabilities in their communities.

To ASEAN Member States

- Acknowledge and respond to the Rohingya refugee situation as a regional problem that requires a comprehensive plan of action that provides support to Bangladesh and effective protection for Rohingya refugees through regional and extra-regional responsibility sharing.

- Press Myanmar to meet all conditions necessary for voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of Rohingya refugees, including ending the systematic persecution of the Rohingya population and holding accountable those responsible for grave crimes.

- Consider a regional refugee resettlement plan, particularly focused on family reunification, for refugees with family members living in other countries in the region.

- If a resurgence of Rohingya boat departures becomes evident, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand should not resume maritime pushbacks, as they have in the past, but rather muster search-and-rescue operations at sea, bring the boats ashore to the nearest safe port, provide humanitarian aid, and give full access to procedures for international protection in close coordination with UNHCR.

Methodology

In May 2018, Human Rights Watch interviewed 31 Rohingya refugees in the Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp and the Leda Makeshift Settlement in Bangladesh who had mostly fled Myanmar since late 2017. We interviewed 18 male and 13 female refugees; two children (ages 10 and 16), 12 in the age range 19-29; five in their 30s; five in their 40s; four in their 50s; two in their 60s; and one in his 70s.

Unless stated otherwise, Human Rights Watch conducted interviews in the privacy of refugees’ own huts—either completely alone or with close family members present—with assurances of confidentiality. Human Rights Watch chose which refugees to interview based on the location of the hut and seeking a demographic balance among refugee subjects. Human Rights Watch told interview subjects that they would receive no payment, service, or other personal benefit for the interviews. All were told that they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time.

The interviews were conducted in English by a Human Rights Watch researcher using two interpreters who translated from Rohingya to Bangla and Bangla to English. The interpreters pledged to respect confidentiality, but the fact that one interpreter was himself a refugee and the other a Bangladeshi national could have affected their candor. Refugees may also have been inhibited from speaking freely because of their lack of legal status in Bangladesh. Finally, because of the context and the fact that the interviewer and interpreters were all men, this study did not include research into sexual and gender-based violence against women and girls, sex trafficking, and pregnancy/termination of pregnancy following rape.

Additional interviews and conversations were held with groups of refugees, with nongovernmental and UN humanitarian agencies, and diplomats of donor countries. We also interviewed the Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner in Cox’s Bazar. To protect confidentiality, pseudonyms are used for all Rohingya refugee interview subjects, unless otherwise stated.

I. Background: A History of Hostility

Bangladesh promptly accepted the sudden and massive influx of Rohingya refugees from Myanmar that swelled in late August and September 2017. Bangladesh also received more than 80,000 Rohingya refugees from violence in Myanmar less than a year before. The number of Rohingya refugees currently in Bangladesh is more than 900,000 when added to the more than 200,000 Rohingya refugees already living in the Cox’s Bazar area from waves of persecution and violence prior to August 2017.[1]

Bangladesh’s openness toward Rohingya fleeing ethnic cleansing in Myanmar contrasts with a history of neglect and rejection. In the past, successive Bangladeshi governments have not respected the fundamental rights of Rohingya refugees. In the 1970s, and again in the 1990s, the government carried out forced returns of Rohingya refugees who fled Myanmar. In 1978, thousands of Rohingya refugees starved to death after Bangladeshi authorities reduced rations in camps to force refugees back.[2] In the 1990s, Bangladesh compelled Rohingya to “volunteer” to return and carried out several rounds of mass deportations, which stand among the darkest chapters in the history of the UN’s refugee agency, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). [3]

Since the early 1990s, the Bangladeshi government refused to register at least 200,000 Rohingya refugees living mostly in the Ukhiya and Teknaf subdistricts of Cox’s Bazar district. It barred humanitarian agencies from assisting all but about 10 percent of the Rohingya refugees who were housed in the two official camps dating from the early 1990s. For many years, massive numbers of unregistered Rohingya refugees lived on the margins in Bangladesh without rights to secondary education, livelihoods, marriage, and freedom of movement, in what one UNHCR study said “mirrored” restrictions they lived under in Myanmar.[4]

The Bangladeshi government’s negative attitude towards Rohingya asylum seekers and refugees continued after an outburst of violence against the Rohingya in Rakhine State in 2012 led to large numbers of Rohingya attempting to enter Bangladesh.[5] The Bangladeshi government refused to allow the fleeing Rohingya to enter the country, and pushed them back to Myanmar.[6] Moreover, in an attempt to discourage more Rohingya from entering, the government ordered NGOs to stop providing services to Rohingya already in Bangladesh and blocked the resettlement of Rohingya to third countries.[7]

The decades-long involvement of UNHCR in Bangladesh has substantially impacted the work of international humanitarian agencies in the current crisis. For years, the Bangladeshi government had insisted that UNHCR’s mandate only covered the 29,000 to 34,000 registered “refugees” living in the two official refugee camps of Kutupalong and Nayapara, and that it had no right of access to the more than 200,000 displaced Rohingya “migrants” living in the same Cox’s Bazar area, many in makeshift camps alongside the official camps. [8] The government instead tasked the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which lacks a protection mandate, as the lead agency for providing humanitarian services for “undocumented Myanmar nationals.”[9]

The Myanmar military’s ethnic cleansing campaign that began in late August 2017 makes for a clear-cut prima facie case for the Rohingya to receive refugee status based on a commonly shared well-founded fear of being persecuted on account of nationality, religion, and similar grounds. Under such circumstances, UNHCR is the only international organization mandated to protect and assist refugees. Yet, at the height of the influx in August and September, Bangladesh delayed delegating this responsibility to UNHCR, preferring to retain IOM as the lead agency, and continuing to treat all but the old, official refugee caseload as “forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals” rather than refugees. [10]

II. An Ad Hoc Response to a Dangerous Situation

UNHCR, the most qualified and experienced UN agency to handle a refugee crisis of this magnitude, has been prevented from providing a coordinated response to the crisis that began in late 2017. This has led to serious repercussions. Although Bangladesh ceded a lead role to UNHCR in the protection sphere, other sectors that in the UN “cluster approach” usually place UNHCR in the lead, such as shelter and camp management, went to IOM, Caritas or the Danish Refugee Council.

More problematically, the authorities divided the Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp operationally between UNHCR and IOM, giving UNHCR responsibility for the northern half and IOM the southern half. “IOM and UNHCR have pursued different approaches in their respective camps, leading both to inconsistency and delays in service delivery,” reads a May 2018 Refugees International report. “In practice, there is little clarity in the lines of reporting or ultimate accountability for what happens in the field…The result is a lack of consistency and adherence to quality standards across sectors.”[11] Because the government did not want to vest UNHCR with leadership of the humanitarian response, the UN response was to set up a Strategic Executive Group comprised of the heads of various agencies in Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, to coordinate the response at the national level with an Inter Sector Coordination Group (ISCG) headed by a senior coordinator in Cox’s Bazar. Despite laudable efforts from the various humanitarian actors, the lines of responsibility and accountability remain unresolved.

Placement of the Mega Camp: Topography

As the refugee crisis quickly unfolded, the Bangladesh government made available 4,800 acres of hilly, undeveloped forest land adjoining the relatively small, 1990s-era official Kutupalong Refugee Camp; the expansion site together with the original camp would soon become the world’s largest refugee camp, hosting more than 600,000 refugees.

The Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp sprung up with little regard to deforestation and its consequences. Much of the hilly site was jungle prior to its sudden habitation starting in late August 2017. “Our entire village came together and settled on this spot,” said Amanat Shah, 19, who arrived on September 2. “At first this was a jungle, but we cleared it. Now there are no trees.” His hut now sits on a densely packed steep slope with almost no vegetation to keep the clay-sand mix under him from eroding or suddenly sliding away, particularly during monsoon rains.

Population Density

At the Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp, many refugees are crammed into very little space. The UN Joint Response Plan (JRP) for March-December 2018 flatly declares: “Congestion is the core humanitarian and protection challenge.”[12] Besides the aggravating circumstances of topography and climate, refugees living in close proximity are at heightened risk of communicable diseases, fires, community tensions, and domestic and sexual violence.

The chart on the following page, based on drone imagery and field mapping conducted by UNHCR’s Site Planning unit, calculates population density based on usable land areas within the camps; non-usable areas are those prone to flooding and landslides.[13] As the chart shows, one of the camps (Camp 6) has as little as 0.63 square meter per person. Excluding Camp 20, which at the time of this chart had just expanded but not yet been populated with refugees being relocated from landslide-prone areas,[14] the average usable space per person in the rest of the original Kutupalong Camp and the expansion camps is 10.7 square meters per person. The SPHERE Handbook’s recommended minimum surface area is 45 square meters per person when planning a refugee camp (including kitchen and vegetable gardening space).[15] The actual surface area per person (excluding garden space) should not be less than 30 square meters per person.

The ISCG’s July 5 situation report notes that “the overarching challenge for the shelter response remains the lack of suitable land to decongest the camps and construct shelters which meet the SPHERE minimum standards, are capable of withstanding the climatic weather conditions and are adequate for meeting the protection needs of women and children.”[16] The US$136.6 million requirement for shelter and non-food items was only 14 percent funded at the time of the report, and the ISCG noted that “efforts to upgrade shelters continue to be hampered by delays in funding, project approvals for NGOs, and supply chain of shelter materials.”[17]

|

Camp |

Total Families |

Total Individuals |

Useable area (sqm) |

% useable area |

Average usable area per person (sqm) |

||||

|

Camp 6 |

5,754 24,712 |

15,549.13 |

4% |

0.63 |

|

||||

|

Camp 7 |

9,236 |

38,905 |

187,746.25 |

26% |

4.83 |

||||

|

Camp 18 |

6,807 |

27,832 |

215,867.55 |

29% |

7.76 |

||||

|

Camp 17 |

3,157 |

13,400 |

105,265.74 |

12% |

7.86 |

||||

|

Camp 8W |

7,534 |

32,761 |

261,919.44 |

34% |

7.99 |

||||

|

Camp 10 |

8,003 |

34,429 |

275,403.52 |

56% |

8.00 |

||||

|

Camp 2E |

6,823 |

28,450 |

231,810.44 |

60% |

8.15 |

||||

|

Camp 11 |

7,482 |

32,947 |

291,155.08 |

62% |

8.84 |

||||

|

Camp 3 |

9,098 |

39,165 |

370,579.30 |

81% |

9.46 |

||||

|

Camp 9 |

8,642 |

36,650 |

364,589.86 |

56% |

9.95 |

||||

|

Camp 2W |

5,646 |

24,800 |

251,214.12 |

63% |

10.13 |

||||

|

Camp 1W |

9,379 |

40,654 |

453,408.96 |

85% |

11.15 |

||||

|

Camp 4 |

7,452 |

30,313 |

358,275.42 |

32% |

11.82 |

||||

|

Camp 5 |

6,199 |

25,794 |

312,596.39 |

51% |

12.12 |

||||

|

Camp 8E |

7,695 |

33,333 |

433,694.96 |

45% |

13.01 |

||||

|

Camp 13 |

9,586 |

40,911 |

566,311.36 |

76% |

13.84 |

||||

|

Camp 1E |

9,166 |

39,815 |

608,228.12 |

96% |

15.28 |

||||

|

Camp 19 |

4,383 |

19,099 |

340,459.65 |

48% |

17.83 |

||||

|

Kutupalong RC* |

3,778 |

18,877 |

340,824.72 |

89% |

18.06 |

||||

|

Camp 12 |

4,895 |

22,064 |

487,402.76 |

77% |

22.09 |

||||

International guidelines recommend the average camp area should be 45 square meters per person, or minimally 30 square meters per person, excluding kitchen and garden space.

Climate

Bangladesh is hit by about 40 percent of the world’s total storm surges.[18] On average for the past 140 years, a cyclone has made landfall in Bangladesh about once a year, usually hitting in April-May during the early rainy season, or in October‐November during the late rainy season.[19] In 1991, Cyclone Gorky killed 139,000 people in Cox’s Bazar and Chittagong. [20]

Since that time, Bangladesh has taken preparedness measures, such as positioning of hard shelters and well-executed evacuation plans, and mortality rates have dropped dramatically. But the measures that Bangladesh has taken to protect its own citizens have not been extended to the primarily Rohingya refugee population in Cox’s Bazar. The most recent cyclone to hit Cox’s Bazar, Cyclone Mora in May 2017, damaged an estimated 70 percent of refugee huts and 80 percent of latrines in unofficial camps and makeshift settlements, and severely damaged 20 percent of huts in the official Kutupalong camp.[21] When Cyclone Mora struck, camp conditions were poor, but did not approach the congestion and topographical challenges now present in the Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp.

Fear of heavy rains and wind is universal in the camps. Tasmin, a mother of nine children, expressed her fears, saying she was unaware of a cyclone shelter to which her family could be evacuated or any plan for moving them to a safe location: “I am afraid about heavy rains. I don’t think this hut will withstand them. There is no plan to relocate us. There is no evacuation plan if a cyclone comes because there is no shelter to take us to.”[22]

Other refugees said they were aware of emergency evacuation plans, but they could not provide details about what they were supposed to do in the event of an emergency. “There is an evacuation plan,” said Noor Hakim, 46, a mother of nine. “They say when they raise a red flag we should go to another safe area, but I don’t know where that place is.”[23]

International Context

There are generally considered to be three durable solutions to any refugee situation: repatriation, local integration, or third-country resettlement. None of them appears to be feasible, even as a partial solution, for the Rohingya refugee crisis for the time being. Repatriation cannot happen until the Myanmar government undertakes fundamental, demonstrable and lasting reforms relating to the status and protection of the Rohingya, among other issues. Bangladesh rejects integrating the refugees, and its history with respect to registered and unregistered Rohingya refugees who have been living in protracted, abysmal conditions for decades is testament to that. Finally, third-country resettlement has only directly benefitted a small fraction of the world’s refugees. In the current political climate, opportunities for refugee resettlement are shrinking, particularly for Muslim refugees,[24] and the choice of which refugees to resettle is increasingly driven by migration management priorities, for example, as part of the migration deal between the European Union and Turkey.[25]

There is also a regional migration dimension to the Rohingya situation. Although few of the Rohingya refugees have taken to boats since 2017, for many years previously, Rohingya displacement has had a broader regional dimension. UNHCR estimates that between 2012 and 2015, about 112,500 Rohingya migrants and asylum seekers embarked on boats in the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea.[26] Most of those who survived the journey, often in unseaworthy boats, disembarked in Malaysia, but others landed or ended up in Thailand, Indonesia, and even among the asylum seekers and refugees held on Australia’s offshore sites on Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island and Nauru.[27] The maritime dimension has not only expanded the scope of this refugee situation regionally, but has also triggered concerns about human trafficking, which remains a cause of fear and anxiety to many of the refugees living in the camps.[28]

Donor countries have neither provided significant resettlement nor fully funded the humanitarian appeals for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. As of this writing, the US$950.8 million appeal to meet humanitarian needs through the end of 2018 was only 26 percent funded, a shortfall of $701 million.[29] In interviews with Human Rights Watch, humanitarian workers in Cox’s Bazar and Dhaka lamented not only the steep falloff in donor response from the highly publicized emergency in 2017 when the appeal was 77-percent funded, but also the slowness of the 2018 response. “The main donors are holding back their funding,” a well-placed humanitarian official in Cox’s Bazar said. “They prefer to respond after a disaster has struck rather than funding to prevent a disaster from happening. Their thinking seems to be, ‘Why donate now when everything we put in will just get washed away.’”[30]

There is also the political dimension to the crisis. When the UN Security Council delegation visited the region in April 2018, including the mega camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina told the delegates she had called on the countries bordering Myanmar—China, India, Thailand, and Laos—to work together to pressure Myanmar and resolve the refugee issue.[31] The lack of any meaningful Security Council action following the delegation’s visit suggests the hopes that many Rohingya refugees are pinning on the international community to make their return possible are misplaced.

III. A Highly Traumatized Refugee Population

In general, the Rohingya refugees who arrived in Bangladesh after August 25, 2017 have experienced high levels of trauma. Following the coordinated attacks on security force outposts in northern Rakhine State by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), Myanmar military and other security forces, assisted by ethnic Rakhine militias, launched large-scale operations against the Rohingya population. Refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch have consistently said they fled direct attacks on their villages. Human Rights Watch, the UN, other NGOs, and the media have documented numerous attacks on Rohingya villages involving massacres, killing, rape and other sexual violence, and mass arson.[32] Some Rohingya who fled were killed or maimed by landmines laid by soldiers on paths near the Bangladesh-Myanmar border.[33] Satellite imagery showed that more than 362 primarily Rohingya villages were either substantially or completely destroyed.[34] Many of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they had experienced security forces shooting on their village and witnessed killings and injuries; some were themselves wounded. Such traumatic experiences were still raw for many of the refugees in the interviews we conducted for this report.

Jamal, 28, from a village in Maungdaw Township, hid in a grove of mango trees when uniformed soldiers entered his village. At the time, his 21-year-old sister, Zuhara (her real name), was in labor, delivering a baby with the help of two midwives, Hasena (real name), 50, and Nawmena (real name), 22. From 300 feet away, Jamal said that he saw five or six soldiers drag his sister and the other two women out of the compound and slit their throats, killing the newborn as well: “I heard the screaming and watched them being slaughtered.”[35]

Yakub, 30, described killings from an army attack on his village in Rathedaung Township, in mid-September, providing Human Rights Watch with the names of four people he witnessed being killed as well as the names of two soldiers from a nearby base who carried out the killings. Because his village was surrounded by predominantly ethnic-Rakhine-populated villages, Yakub and other survivors did not leave the village immediately after the attack:

After that attack, I stayed one month and two days in my house. The army knew I was there. They said, “No problem, stay there.” But during that whole time, they were taking women from our village and bringing them to the base. They would keep the women there for four or five days and then return them, raped. My wife was pregnant at the time. The soldiers beat her and the baby was lost.[36]

Female-headed households are common in the refugee camps because of the deaths and disappearances of many men. Human Rights Watch visited 27-year-old Daula, living with her mother and seven children in a hut in Thainghali, Camp 17. She tearfully recounted the day, August 27, 2017, she fled her village in Rathedaung Township, “I watched from 15 to 20 feet away my husband being killed,” she said. “The army shot him and took away my father and sister. They are still missing. We don’t know their fate.”[37]

Firuzaa, 20, remembers fleeing her village in Maungdaw Township. Her husband was carrying her one-year-old daughter, Yasmin, in his arms. One bullet struck his shoulder. Several hit Yasmin, killing her.[38]

IV. Refugees at Risk

Living conditions in the overcrowded, muddy mega camp are difficult, at best. However, many of the refugees that Human Rights Watch interviewed were reluctant to express any criticism of Bangladesh, their hosts, or suggest that conditions were better in Myanmar. Even refugees perched precariously on steep, sandy slopes with rain pouring down during the interviews, would say, “I feel safe,” when first asked. Their current views about their security need to be considered in the context of the situation from which they fled in Myanmar.

This tension at times revealed itself in interviews. Amir Hussein, 24, described how his 11-year-old daughter was shot multiple times as they escaped Myanmar, and Bangladeshi border guards rushed her to a hospital. His 23-year-old wife, Sameera, was silent as he told the harrowing story. When asked about life in the camp, Amir Hussein said, “I am satisfied with camp conditions.”[39]

At that point, Sameera could remain silent no longer:

There is no safe drinking water here. The toilets are terrible. I want to leave this place because it is not safe. I feel fear at night. I hear gunshots some nights. I am afraid there will be landslides here because we live on a steep slope. When it rains the water comes inside our hut, so we keep making barricades to keep the hut from being flooded, but it is only being held up by sandbags. I fear elephants. I saw them here. One elephant came to this area and killed a person. If any group offers to relocate us to a good, safe site, I would like to move.[40]

But even Sameera ended on a positive note: “Everything else is fine.”

Natural Disaster

The looming threat over Rohingya refugees is the likelihood that the Cox’s Bazar region will be hit by a cyclone or comparable high winds and storm-surge flooding. In May, refugees were busily shoring up their huts, construction crews were working hard to build safer locations to accommodate people, and first responders were conducting drills to mitigate disaster. Notwithstanding these efforts, the camps remain highly vulnerable to catastrophic weather events.

Climate change has amplified these risks.[41] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)[42] describes Bangladesh as one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change, “in terms of its exposure to extreme events and lack of capacity to cope and adapt.”[43] The IPCC warns, “South Asia’s climate is changing and the impacts are already being felt.”[44]

During the reporting week of May 14-21, the ISCG reported more than 9,000 people affected by storms and landslides and more than 1,000 huts damaged.[45] The ISCG’s June 13, 2018 situation report estimated that 215,000 refugees in the Cox’s Bazar district were at risk of floods and landslides, of which 42,000 were at very high risk.[46] Its July 4, 2018 situation report said only 19,500 had been relocated from high-risk locations.[47]

In its April 2018 analysis of cyclone preparedness, NPM-ACAPS, an analysis unit for IOM, concluded, “There are no evacuation plans for the Rohingya population.”[48] It attributed the lack of evacuation plans to the government’s movement restrictions on the refugees, scarcity of land, and a lack of usable, stable structures in which to relocate people. Since that assessment, government authorities and humanitarian agencies have developed evacuation plans, but the impediments highlighted in April persist as worsening weather conditions made the need to implement them more likely.

Not only are the refugees living in flimsy bamboo and tarp huts, many of which are accessible only by foot on slippery, narrow, mud paths on steep hills, but their community structures are similarly unstable and insecure. A consequence of the Bangladeshi government’s resistance to any suggestion of permanence is that the “temporary learning centers” (TLCs) must be constructed using the same inadequate foundations and non-durable materials as residential huts. Normally in times of natural disaster, schools can serve as emergency community evacuation centers, but in this case the TLCs are as vulnerable as the huts surrounding them, with 350 of them at risk to flooding and landslides.[49]

Physical Security

In planning emergency settlements, the SPHERE Handbook states that due consideration should be given to potential tensions between refugees and the local population, and to security risks for women and girls, such as physical and sexual assault, domestic abuse, and trafficking.[50] Refugees who spoke to Human Rights Watch expressed fears relating to trafficking, missing children, and safety at night, but they were not able or willing to provide details of specific events they experienced or witnessed personally. Firuzaa, a 20-year-old woman in the Leda Makeshift Settlement, said:

I am afraid of thieves stealing our rice. Second, I am afraid when I go to the latrine at night. There have been incidents. Near another house here, local villagers came and tried to take a woman. It wasn’t me, but I’m afraid. I have two teenage sisters and I fear for them. There is a volunteer patrol. We didn’t have patrols earlier, but now they patrol. If they fail to maintain security, they call the police or army.[51]

As with refugees’ unwillingness or inability to provide names and details relating to abductions, they were similarly reluctant to discuss domestic or sexual abuse within the refugee community. Most women who spoke to us said, however, that they will not go out alone at night for fear of harassment or abduction, and refugees in both the Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp and the Leda Makeshift Settlement said they had organized volunteer patrols with some assistance from the Bangladeshi security forces.

Hamida, 52, in Camp 11, provided a mostly positive assessment of camp security to Human Rights Watch. She said her principal problems are the quantity and quality of food and water, as she manages her personal security:

The latrine is not good and it is too far away. I have someone take me to the latrine if I have to go at night out of fear. We have volunteer patrols to keep order and the majhi [block leader] is good. Even though he is a man, women do have a voice.[52]

As with many other refugees we spoke to, she qualified her expression of fear about going out a night in the camp: “We are free and no longer live in fear in Bangladesh.”[53]

The Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner (RRRC) and humanitarian agency officials working in the area told Human Rights Watch there are rising tensions between refugees and the local host community.

Despite these issues, refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they still felt supported by the local community and did not express concern about relations with local residents (beyond not being paid or otherwise being exploited by employers). “We are on good terms with the local people here,” said Ahammed Hashim, a 65-year-old man living in the Leda Makeshift Settlement. “Unlike Myanmar.”[54]

Nineteen Rohingya refugees have reportedly been murdered in the camps from December 2017 through June 2018.[55] In response to serious security incidents, including the June 18 murder of a community leader who was stabbed 25 times by a group of men in the middle of a busy pathway in the mega camp, Bangladeshi police have increased their presence in the camps. [56] The attacks have primarily been blamed on personal rivalries or criminal activity, but the murders of community leaders have led to suspicion that the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army—a Rohingya militant group—might be responsible.[57] Media reports cited Cox’s Bazar Police Superintendent A.K.M. Iqbal Hossain as saying that a special force of 2,400 men was being formed to guard the camps.[58]

Dil Mohammed, 18, living in Thainghali camp, said he has not personally felt pressure to join gangs or armed groups:

There is a gang near the camp, but I don’t bother them and they don’t bother me. It is a mix of Rohingya and Bangladeshi guys, but they are established people, not new arrivals. I am afraid of robbers and elephants. And I’m afraid that my children will be kidnapped. I have heard about robberies, but I have not been robbed myself. If there is a big crime, the Bangladesh police handle it, but for petty crimes, the majhis [block leaders] and volunteers solve the problem. The army here is good. We trust the Bangladesh army.[59]

The findings of Xchange’s May 2018 survey of more than 1,700 Rohingya refugees in 12 camps found that 99 percent of respondents said they felt safe during the day in the refugee camps and 96 percent said they felt safe at night. Of the 4 percent who said they did not feel safe at night, 80 percent were women, who listed their reasons for not feeling safe as: wild animals, particularly elephants; potential robbery; “murderers”; and human traffickers.[60]

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH)

Properly functioning water and sanitation systems are critical to the safe functioning of refugee camps from their inception. But this foundational infrastructure was flawed from the outset of the crisis by the lack of an adequately planned and coordinated emergency response. “Planning of the extension camps is largely absent and there is no infrastructure for good sanitation and drainage,” said Maya Vandenant, at the time chief of health for UNICEF Bangladesh. “We see that after the rains, water flushes the camps everywhere, including the toilets.”[61]

Not following international standards from the beginning has consequences as refugee camps consolidate. “The right to water and sanitation is inextricably related to other human rights, including the right to health, the right to housing and the right to adequate food,” says The SPHERE Handbook. “As such, it is part of the guarantees essential for human survival.”[62]

The hurried and haphazard construction of the Kutupalong-Balukhali mega camp meant that positioning of latrines, as well as their maintenance, has been problematic. The inadequate quantity and quality of latrines has heightened the risk for outbreaks of acute watery diarrhea and other disease. [63] A July 4, 2018 ISCG situation report said 6,594 latrines had been decommissioned and another 28,193 emptied “in the ongoing decommissioning and desludging exercise.”[64]

The limited number of toilets and poor maintenance of them was an often-expressed complaint to Human Rights Watch. Refugees’ frustration with the quantity and quality of toilets has been exacerbated by the alleged unresponsiveness of their block leaders to fixing the problem. “I told the majhi that the toilets are full, but he takes his time,” said Sayyid Salam, 40, a father of six living in Camp 16. “I have complained repeatedly, but they are still not fixed.”[65]

According to the SPHERE Handbook, latrines and other disposal systems must be at least 30 meters away from water sources.[66] The Joint Response Plan (JRP) for 2018 noted that latrines had been built too close to water sources, shelters, and steep slopes, and that many latrine pits did not maintain a minimum depth of five feet. The result was that 50 percent of samples of water at its source and 89 percent of household water samples were found to be contaminated.[67]

Nearly every refugee interviewed by Human Rights Watch put the lack of safe drinking water at the top of their list of living-condition problems. There is not enough water, people get sick after drinking it, and they have to walk long distances and stand in long queues to get it. “To get drinking water we have to go to the other side of the main road,” said Noor Haba, a 26-year-old mother of four. She claimed three or four people were struck and killed by cars while crossing the road to get water, but Human Rights Watch could not confirm the information.[68]

High levels of salinity and scarcity of potable water in the Teknaf subdistrict makes potable water there particularly scarce. In the Leda Makeshift Settlement, where water was being trucked in, it has become a source of increasing tension among the refugees and with the local host community. Firuzaa said, “We have problems with drinking water and sometimes people get into fights when queuing for water.”[69]

Despite the critical importance of water, sanitation, and hygiene to public health in a congested refugee camp, WASH is one of the most underfunded sectors in the humanitarian appeal. As of July 10, 2018, the WASH sector was 11.3 percent funded, with only $15.4 million received and a funding gap of $121.3 million.[70]

Food and Fuel

Lack of food was one of the most common complaints among refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch. “I need more food,” said Osman, 18. “The rice, dahl, and oil are not sufficient. We need meat and fish.”[71] The Xchange survey of more than 1,700 refugees in 16 camps similarly found that 66 percent of all respondents said they did not have sufficient food, water, and firewood for their households.[72]

UNHCR’s April 2018 survey of refugees’ priority needs in 29 camps and settlements in Ukhiya and Teknaf, including all the subcamps within the mega camp, showed food to be the top priority need as expressed by the refugees in most camps. In 21 of the 29 camps surveyed, 50 percent or more respondents listed food as their priority need, and in seven of those camps, more than 70 percent of respondents said food was their priority need.[73]

Closely related to the lack of nutritious food beyond the basic ration was the lack of income to buy food. The ISCG reported in July it had only reached 35 percent of the 350,000 people it had targeted for cash/in-kind livelihoods support.[74]

The need for food is also inextricably linked to the need for cooking fuel. So far, the fuel most commonly used in the camps for cooking is firewood. Even when families have enough food, a lack of fuel can make it impossible to cook the rice and lentils they receive as rations. Kadir Ahmed, 24, living in a small hut on steep, sandy slope in Camp 9 with his wife, mother-in-law, sister-in-law, and four children, said the shortage of fuel was his biggest problem:

We sell our rice to purchase firewood. Sometimes we burn dried leaves. We are not allowed to gather firewood outside the camp. There are nearly no trees out there in any case. They have all already been cut.[75]

Gathering firewood outside the camp can be dangerous for children. Firuzaa said, “I send the children out to gather firewood, but if the Forestry Department catches them, they hit them and threaten them with knives.”[76]

Like WASH, food has proven to be at the bottom of donors’ giving list. While the whole JRP appeal was only 26 percent funded in early July 2018, the food sector was only 20 percent funded—US$48.3 million received halfway through the year, with a gap of $192.6 million.[77]

Health

The Bangladeshi government and humanitarian agencies have worked hard, and, for the most part, successfully, to vaccinate refugees and prevent outbreaks of disease, but despite efforts to contain the outbreak of diphtheria, 8,000 cases were reported, as of July 4, 2018.[78] With the rainy season, the risk of water-borne disease becomes significantly higher. Heavy rains pose a particular challenge to a precarious water and sanitation system and the risk of contaminated water is an urgent public health concern.

Healthcare providers have so far prioritized prevention of epidemic outbreaks of infectious disease, but the response remains reactive and ad hoc. The baseline assessment in the UN’s Joint Response Plan for March-December 2018 for providing access to health services to prevent and respond to diseases with epidemic potential said, “There is no standardized system in place at this time.”[79]

When the May 2018 Xchange survey asked 1,700 camp residents to list the three most difficult aspects of life in Bangladesh for themselves and their family, the top response, expressed by 70 percent of the respondents, was “health issues.”[80]

Poor water and unsanitary conditions put populations at high risk of health problems. “Our biggest problem is the lack of safe drinking water,” said Tasmin, a 42-year-old mother of nine in Camp 2W:

The children have gotten diarrhea and other sicknesses from impure water. Our health conditions are deteriorating. I feel weak. We have gone to clinics when we get sick and received medicine. When I take the medicine I feel better, but then I get sick again.[81]

Rohingya women and girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch in September 2017 reported extremely low access to sexual and reproductive health care in Myanmar. Restrictions on freedom of movement were also extended to women in obstructed labor, sometimes with deadly results.[82] Access to sexual and reproductive health care, including to “menstrual regulation,” safe abortion care in the first trimester of pregnancy (which is legal in Bangladesh for all women and survivors of sexual violence) and other forms of basic health care have been limited in the mega camp.[83] There were some improvements reported by health NGOs in mid-2018, but Bangladeshi government staff have been slow to issue work permits and permission for some programs, stymying access to basic sexual and reproductive health care for women and girls.[84]

There is a near absence of psycho-social support for refugees experiencing psychological harm, post-traumatic stress, and other mental health conditions. “Mental health is one of the biggest, yet most neglected, needs in the camps,” said Lynn van Beek, humanitarian affairs officer for Médecins Sans Frontières. “The trauma from Myanmar is compounded by the stresses here.”[85]

Human Rights Watch has documented Myanmar security force use of gang rape and other forms of sexual violence against Rohingya women and girls as part of the 2017 ethnic cleansing campaign.[86] Sexual violence, including the use of rape targeting an ethnic group or other population, often leads to physical and serious mental health complications for survivors, including: post-traumatic stress disorder, complex trauma, anxiety, or depression.[87] In 2017, severe crowding in the limited medical facilities in Bangladesh together with stigma and a lack of knowledge about how to access assistance obstructed Rohingya rape survivors from getting medical care. Increased outreach, including in the form of individual case management and the establishment of women-friendly centers, has improved the situation, but NGOs believe many survivors are still not accessing long-term trauma care and other key assistance.[88]

Older Refugees and Refugees with Disabilities

Everyone in the camp has trouble navigating the steep and slippery footpaths that are often the only way to move in and out of their huts. For people with disabilities, daily life in the camps is treacherous and accessibility to meet basic needs badly compromised.

Yasmin, orphaned at 16, showed Human Rights Watch the bullet that was removed from her buttocks. She was shot fleeing her village, and her sisters carried her to Bangladesh where she was treated for her wounds. Yasmin said she has ongoing problems but cannot afford medicines and has been given no assistance to support her mobility. Although she qualifies on several grounds for the registration category of “extremely vulnerable individual,” Yasmin said she had received no specific services or aid on account of her disability or because she is an orphaned minor who only has the support of her sisters:

It is very difficult to walk in the camp. I can’t move around by myself. I don’t have a cane. I need to lean on my sisters to walk. My hut is very small and has no bathroom, so I need my sister to take me to the bathroom at night. The drinking water supply is very distant from my hut. I have a registration card, but I don’t know anything about “vulnerability.” I don’t get any different food or assistance than anyone else. I need medicine, but I have no money, so I don’t get any. Three times NGOs have come to my hut to interview me, but they haven’t given me any support. I don’t go to school. I don’t have an education. I am unable to go to school because of my injury.[89]

Yasmin also fears what will happen to her when the rainy season gets worse: “Our hut is not strong. When a strong wind or rain comes, a water channel forms right next to my hut.”[90]

Kahimullah, age 70 and partially blind with respiratory problems and difficulty walking, is not receiving any specialized services or assistance. He and his wife live on a steep incline in a tiny hut next to a fecal sludge pond. Despite living in a dreadful and dangerous place and the multiple disabilities that make it difficult for him to access services, Kahimullah said, “This is not my land. I am thankful to Bangladesh. This is enough for me.” He added:

I feel danger where I live, but I have no other options. If strong winds and rain come, maybe someone will come to help us. There is a bad smell here and we have lots of mosquitos. I have a donated mosquito net, but it is not sufficient. The toilets are not clean. Because I am blind, I can’t go outside. I can’t get food rations, I have no money for fish or meat. I am dependent on humanitarian relief.[91]

Distant and inaccessible latrines and toilets were the most common complaint from older people and people with disabilities. Arefa, a 60-year-old woman with hypertension who Human Rights Watch visited as she was lying on the floor of her hut with an IV bottle dripping into her arm, said, “I need help to move. There is no latrine or toilet nearby. I am not able to walk by myself. I need someone to help me to walk.”[92]

Challenging on another level are people with intellectual and psychological disabilities, which may not be recognized at all, and, even if recognized, have no course of support or treatment, which was also lacking in Myanmar. Hamida, 52, said her 14-year-old son has had an intellectual disability since birth. She said he saw a traditional healer in Myanmar who tried magic on him, but he has never had an evaluation from a medical professional, treatment, or needed care. “When we were registered as refugees here in the camps, I don’t remember anyone noting his disability. There is no program for him here. He does not go to the learning center.”[93]

Bangladesh ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and its Optional Protocol in 2008. Under article 11 of the CRPD, Bangladesh is responsible for ensuring the protection and safety of persons with disabilities in situations of risk, including armed conflict, humanitarian emergencies, and natural disasters.[94]

V. Legal Protection: Respect for Refugee Rights

The Bangladesh government has shown strong respect for the principle of nonrefoulement since the current Rohingya crisis began in late 2017. At a time when many other countries are building walls, pushing asylum seekers back at borders, and deporting people without adequately considering their protection claims, Bangladesh has essentially adhered to its customary international law obligation to keep the border open while several hundred thousand Rohingya refugees crossed without inspection over a short period of time. The government has continued to let in another 11,432 since the beginning of 2018 through the end of June 2018.[95] Moreover, UNHCR has not recorded a single instance of refoulement during this crisis, and none of the refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they felt under any pressure to repatriate.

Most refugees who spoke to Human Rights Watch said they encountered no difficulty crossing into Bangladesh. A few said that they were stopped during the daytime, but just crossed the same night. Kahimullah said he spent several days in the no-man’s land at the Tombru crossing, but that Bangladesh border guards finally facilitated his entry into the country:

We walked for four days before crossing to Bangladesh and spent another three days in the no-man’s land at the Tombru checkpoint. At that time the Bangladesh border guards stopped us at the zero point, but then they let us go forward. Many other people entered at the same time as me. The Bangladesh authorities gave us food rations.[96]

Bangladesh is not a party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951 Refugee Convention) or its 1967 Protocol.[97] The country lacks domestic refugee law and has not acknowledged in law that refugees have rights. With the exception of 33,788 registered refugees who arrived in the early 1990s and have lived in two official camps, the original Kutupalong Refugee Camp, housing 14,129, and Nayapura Refugee Camp, in the Teknaf area, housing 19,659,[98] the rest of the refugees are officially registered as “Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals,” a designation that denies them refugee status and any legal rights that would attach to that status.[99]

As it has done with the refugees in the two official camps, Bangladesh should register the Rohingya who have fled Myanmar as refugees. The evidence supporting their claim to refugee status is overwhelming: the Myanmar’s government widespread and systematic campaign of killing, rape, arson, and other grave abuses, which amount to crimes against humanity, and its violations of fundamental human rights against the Rohingya.[100] Beyond the latest atrocities is the longstanding repression of the Rohingya population by successive military and civilian governments in Myanmar. Central is the effective denial of citizenship for Rohingya, many whose families have lived in Myanmar for generations. This, along with repeated confiscation or invalidation of personal documents, has facilitated the creation of the world’s largest stateless population. For decades the Rohingya have been subjected to official restrictions on movement; limitations on access to health care, livelihood, shelter, and education; and arbitrary arrests and detention.[101]

Without a recognized legal status, Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are on a precarious legal footing under domestic law. Without refugee status, they can be denied freedom of movement, access to public services such as education and health care, and access to livelihoods, leaving them vulnerable to arrest and exploitation. Bangladesh, however, is party to the core international human rights treaties, notably the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.[102] The provisions of these treaties largely apply to “everyone” or “all persons,” not just citizens or people with refugee or other immigration status. They protect the rights to freedom of movement, education, highest attainable standard of health, and to a livelihood, among others.

Freedom of Movement

The Bangladeshi government confines Rohingya refugees to the Ukhiya and Teknaf subdistricts. At least 27 army and police checkpoints have been established on the roads of the Cox’s Bazar district, in part, to prevent the refugees from moving into the town of Cox’s Bazar.[103] “I tried to leave two times,” said Suleman, 35, a father of four in camp 16, “but the army stopped and tested me, asking me to speak Bangla and to show a Bangladesh ID, which I don’t have. They were polite, they did not ask for bribes.”[104]

Osman said he made four attempts to leave the restricted area around the camps and was turned back twice by local residents. He said he succeeded in leaving when he paid police at a checkpoint a 200 taka (US$2.40) bribe, and was turned back another time after a policeman at the Morisha checkpoint hit him with a stick:

There were five of us. We had sold some of our cooking oil in return for transport. The police asked for money, but we didn’t have any, so they sent us back to the camps. One policeman asked each of us to pay 500 taka [$5.90] and he would let us pass. He hit me two times on the outside of my thigh with a wooden stick which was about an inch in diameter. It was more to push and intimidate than to hurt me. This policeman hit all five of us the same way. He hit us because we lied at first when he asked us if we were Rohingya. One policeman hit us, and the others watched.[105]

Under international human rights law, Bangladeshi authorities may only limit the movement of people in Bangladesh—citizens and non-citizens alike—if these restrictions are “provided by law…and necessary to protect national security, public order, public health or morals, or the rights and freedoms of others.[106] In addition, these restrictions must be non-discriminatory, in accordance with national law, and be “necessary” to achieve one or more legitimate aims. Any such restrictions on a person’s free movement must be proportionate in relation to the aim sought to be achieved by the restriction, that is, carefully balanced against the specific reason for the restriction being put in place.[107]

The Bangladesh Constitution guarantees free movement to every citizen, subject to “reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the public interest.”[108] While this does not apply to non-citizens like the Rohingya, Bangladesh still needs to comply with international law in its restrictions on their free movement. The basis for restricting the free movement of Rohingya under Bangladeshi law appears to be the Foreigners Act of 1946, which allows the government to order that any “foreigner”—defined as any non-citizen—be required to “reside in a particular place.”[109]

Two aspects of the Foreigners Act raise issues concerning its consistency with international law. First, it does not require that a restriction be necessary to protect national security, public order, public health or morals, or the rights or freedoms of others. A person or group of persons can be restricted to a particular place seemingly for any reason. Second, an order to restrict movement can be applied to “any prescribed class or description of foreigner.”[110] This opens the door for the discriminatory application of the law to particular ethnic groups, like the Rohingya. As well as these concerns, the decision behind the order restricting all Rohingya movement does not appear to have assessed the proportionality of such a move or assessed the necessity of the order on an individualized basis.

At Bangladesh’s May 2018 Universal Periodic Review at the UN Human Rights Council, the head of the Bangladeshi delegation said the refugee influx was having a negative impact on Cox’s Bazar, which necessitated limiting the free movement of Rohingya refugees. He said Rohingya refugees were double the local population, which caused price hikes on basic goods and other strains: “The local people, unable to use their land for cultivation, lose out to the Rohingyas in the labor market affected by lower wages accepted by the Rohingyas. Municipal services in the Cox’s Bazar area has been unavailable to locals since the influx adding more sufferings.”[111] These broad-based and opened-ended grounds for confining Rohingya refugees to the camps do not meet the standards of necessity, legitimacy, and proportionality set out in international law for restricting the right of free movement.

Even though they are now living in poor, overcrowded conditions with restrictions on their rights to move and work, many refugees said that they had comparatively fewer restrictions than in Myanmar. “In Myanmar there were restrictions on freedom of movement,” said Dil Nawaz, a 25-year-old mother of an infant whose husband is missing in Myanmar, of the restrictions on her freedom of movement that have always been part of her life. “In Bangladesh I can go nearby. In Myanmar I could not go as far as I can here.”

VI. Repatriation: Obstacles to the Right of Return

On November 23, 2017, Bangladesh and Myanmar signed an “Arrangement on Return of Displaced Persons from Rakhine State” on behalf of “residents of Rakhine State” who crossed from Myanmar into Bangladesh after the events of October 9, 2016 and August 25, 2017. Neither UNHCR nor the Rohingya refugees themselves were consulted in the drafting of the agreement. The agreement makes no reference to the campaign of killings, rape, and mass arson carried out by Myanmar security forces which caused the forced displacement. It also does not identify the displaced either as Rohingya or as refugees. It established a wholly unrealistic and later abandoned timeline for returns that were to commence two months after the agreement was signed.[112]

In February 2018, Bangladesh presented Myanmar with a list of 8,032 refugees to verify as Myanmar nationals for repatriation. Bangladesh had simply culled the names at random from its registration rolls without first consulting with the refugees on the list to confirm their willingness to return or to have their names and other details shared with Myanmar officials. “The names on the list we prepared were not chosen because they particularly wanted to go back,” Abul Kalam, Bangladesh’s refugee relief and rehabilitation commissioner, told Human Rights Watch. He said that Myanmar had verified 878 names on the list as residents, but that “we have not begun the process of voluntary repatriation for this group.”[113]

Refugees interviewed privately by Human Rights Watch all expressed their preference to go back to Myanmar but described the conditions that needed to be met before they would return voluntarily: Myanmar citizenship, recognition of their Rohingya identity, justice for crimes committed against them, return of homes and property, and assurances of peace and respect for their rights. Osman said:

If Myanmar gives us citizenship and recognizes our Rohingya identity we will return. We also want the return of our land and property. We want security and justice and to be treated equally with the other religions. I would like to go back, but I need the return of my home, property, and citizenship rights. The international community should also maintain peace in our homeland.[114]

An Xchange survey of more than 1,700 Rohingya refugees in 12 camps who arrived after August 25, 2017 found that 98 percent of respondents said they would consider returning to Myanmar, but almost all said they would go back only if certain conditions were met, with the majority mentioning Myanmar citizenship with acknowledgement that they are Rohingya, freedom of movement and religion, and the restoration of their rights and dignity.[115]