Summary

The mayor said, “All thieves must be killed.” He said it was an order.

−Witness to the execution of Fulgence Rukundo on December 6, 2016

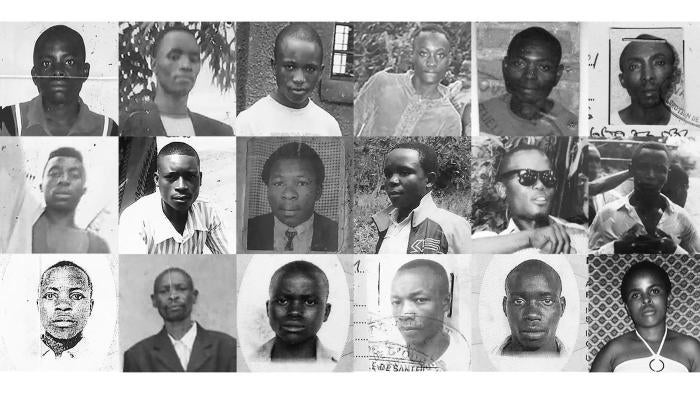

Rwandan security forces summarily executed at least 37 suspected petty offenders in Rwanda’s Western Province between July 2016 and March 2017. Soldiers arbitrarily arrested and shot most of the victims, in what appears to be an officially sanctioned strategy to execute suspected thieves, smugglers, and other petty offenders, instead of prosecuting them. These killings, carried out by and with the backing of state agents, are a blatant violation of both Rwandan law and international human rights law.

Human Rights Watch also documented four enforced disappearances of suspected petty offenders between April and December 2016. The victims’ families believe the security forces killed their loved ones, but their bodies have not been found. In two other incidents documented by Human Rights Watch, in August 2016 and April 2017, authorities encouraged local residents to kill suspected thieves, and they did in fact beat the victims to death.

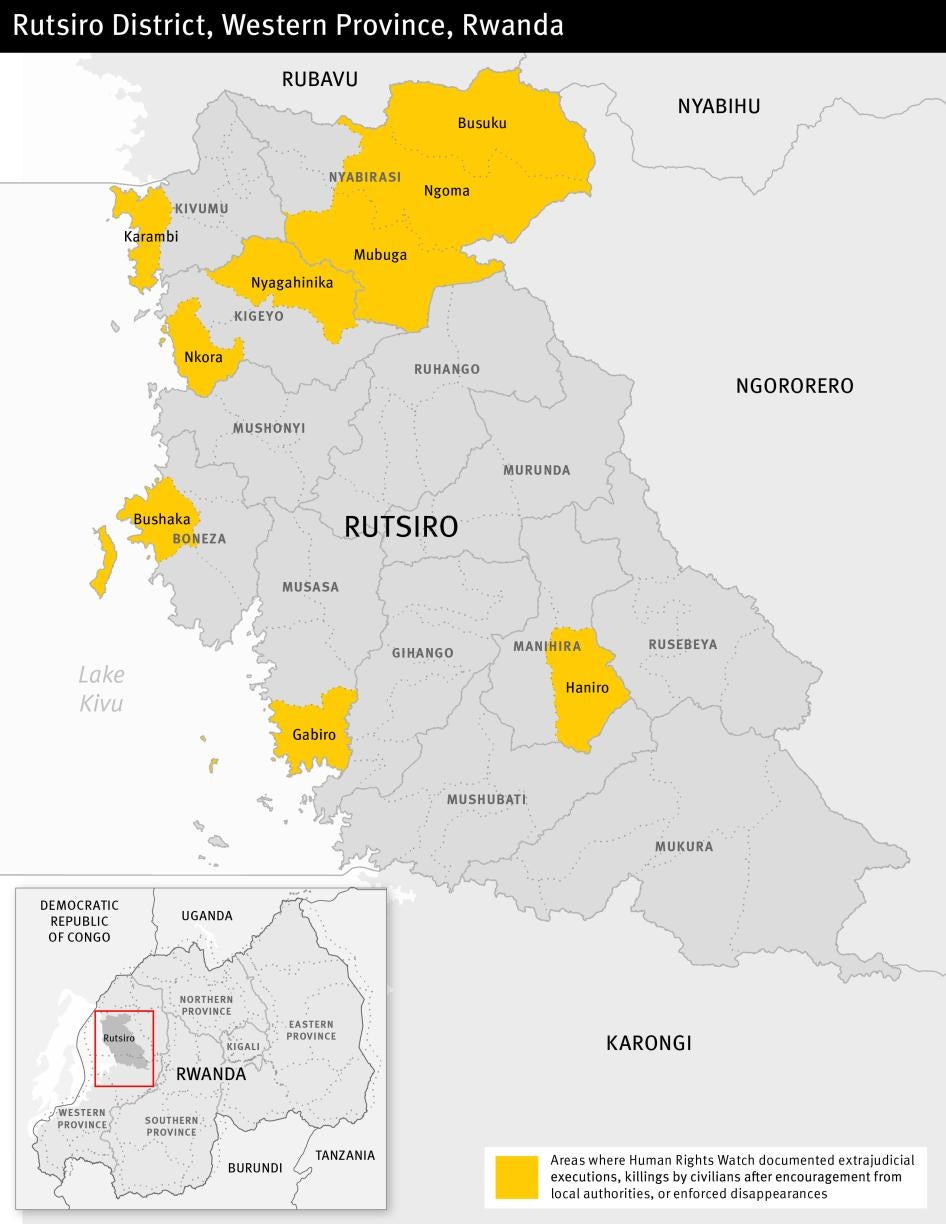

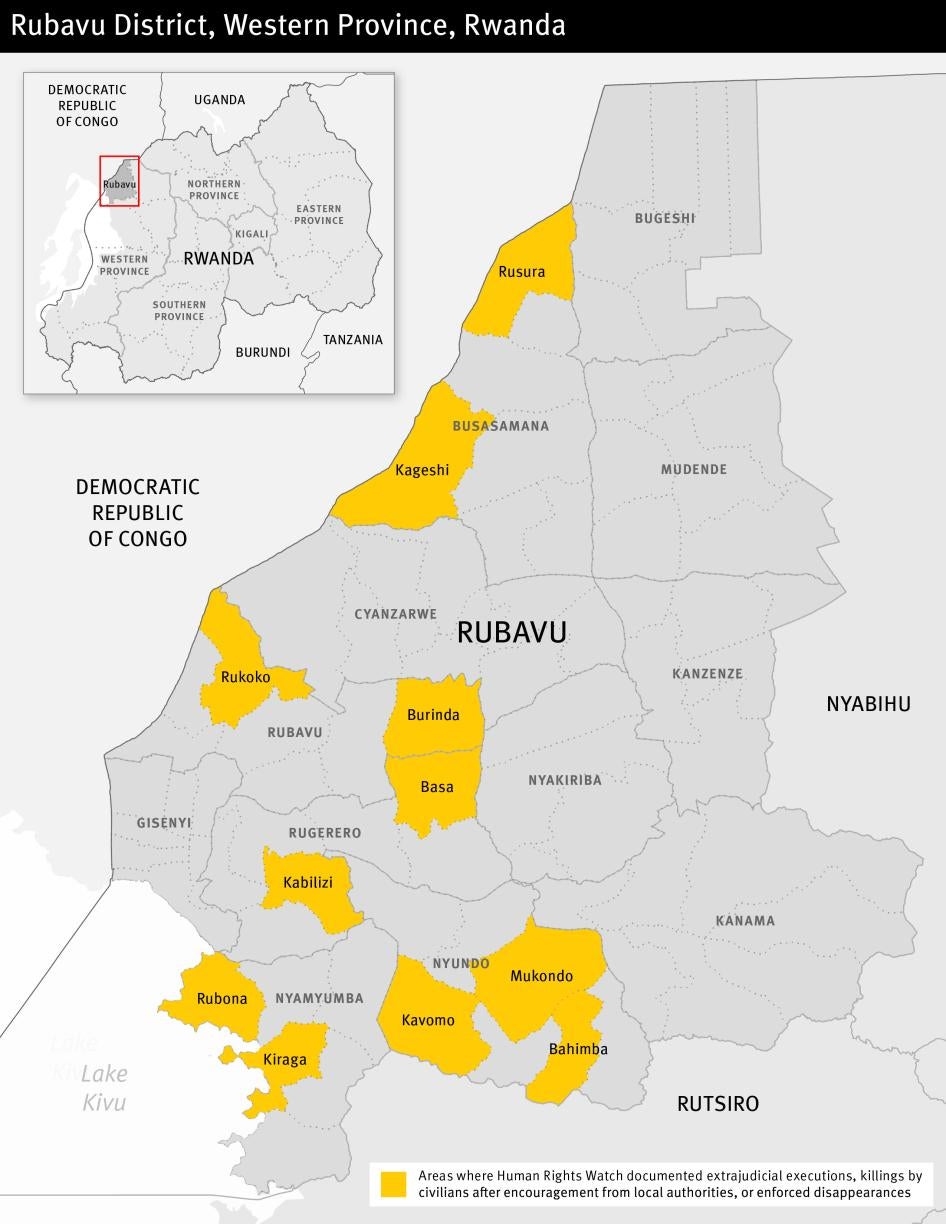

This report documents serious violations committed by the security forces in Rubavu and Rutsiro districts in Rwanda’s Western Province, including extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, and threats against family members and other witnesses to the violations. The report is based on 119 interviews conducted between January and July 2017 with 119 family members, witnesses, government officials, and others knowledgeable about the arrests and executions. Human Rights Watch has received credible reports of at least six other extrajudicial executions that it is continuing to verify, including some cases allegedly committed as recently as June 2017, and some cases in Rusizi district (Western Province) and Musanze district (Northern Province).

Most victims were accused of stealing items such as bananas, a cow, or a motorcycle. Others were suspected of smuggling marijuana, illegally crossing the border from the Democratic Republic of Congo into Rwanda, or of using illegal fishing nets. No effort was made to establish their guilt or bring them to justice. Instead of investigating the killings and enforced disappearances and providing information or assistance to the families, local authorities, including law enforcement officials, threatened some who dared to

ask questions.

Some victims were first arrested by civilian authorities who then took them to nearby military stations. Soldiers then executed the victims at or near the military base, sometimes after ill-treating them in detention. Witnesses who saw the bodies soon after the executions said they saw bullet wounds and injuries that seemed to have been caused by beatings or stabbings. One victim had been stabbed in the heart; another had a cord around his neck.

A man suspected of stealing a cow was arrested by local military and civilian officials and detained for a night in the local government office, where soldiers arrived and beat him and stabbed him in the leg with a knife. The next day, soldiers shot him dead. Soldiers forced another man to carry the remains of the cow he was accused of stealing on his back for more than five kilometers, with the cow’s head on his head. After presenting the victim to local residents, local officials, and the military during a public community meeting, soldiers then walked him to a nearby field and shot him dead. Another man was beaten to death for not turning up for community work he was required to perform.

Members of the military or the police killed at least 11 men on Lake Kivu in Rubavu and Rutsiro districts for using illegal nets known as kaningini while night fishing. There were survivors who described how they had jumped out of their fishing canoes and swam away from the approaching military or police boats. Those left behind in the canoes were shot dead by the officers.

In some cases, other security forces such as the Inkeragutabara, an auxiliary force of the Rwandan army, and the District Administration Security Support Organ (DASSO), a local defense force that supports the police, were involved in the executions.

These killings were not isolated events, but appear to be part of an official strategy. In most of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, local military and civilian authorities told residents after the execution, often during public meetings, that they were following “new orders” or a “new law” stating that all thieves and other criminals in the region would be arrested and executed. In several cases authorities cited the identity of a recent victim and justified his or her killing based on the fact that he or she was a suspected criminal.

These killings, some of which occurred in front of multiple witnesses, are rarely discussed in Rwanda. Given the strict restrictions on independent media and civil society in Rwanda, no local media outlets have reported about the killings documented in this report, and local human rights groups are too afraid to publish any information on such issues.

In December 2016, a coalition of opposition political parties published a press release on several cases of extrajudicial killings in northwestern Rwanda, including some of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch. Soon after publication, the police in Kigali summoned opposition leader Boniface Twagirimana for interrogation on January 12, 18, and 19, 2017, and accused him of spreading unfounded rumors. He was not charged with any offense.

On July 5, 2017, Human Rights Watch wrote to Johnston Busingye, minister of justice, with copies delivered to the ministers of defense, local government and the head of the police, asking for further information on cases outlined in this report and requesting a meeting. The letter is reproduced in Appendix IV of this report and was not answered.

On July 5 and 6, 2017, Human Rights Watch met with five local authorities, including the mayor of Rubavu district and authorities in Nyamyumba sector, Nyundo sector, and Rukoko cell in Rubavu district and the executive secretary in Boneza sector, Rutsiro district. These authorities denied that killings of thieves or criminals had taken place, but one did say that people who illegally crossed the border had been killed for failing to stop when ordered to do so by soldiers, and that this was for security reasons.

The Rwandan government should ensure an immediate end to the summary executions of suspected criminals by security forces. They should also ensure that thorough, impartial investigations into these serious violations are conducted, including to establish how and with whom any policy originated; and that those responsible for the violations be held accountable. Victims’ families should be compensated for the unlawful killings.

The Rwandan government should also respect the presumption of innocence, ensure anyone accused of a crime receives a fair trial, and enforce without exception an absolute prohibition on criminal punishment for anyone not convicted in a court of law.

Recommendations

To the Government of Rwanda

- Investigate and prosecute as appropriate, in fair and credible trials, individuals from the Rwanda Defence Force, the Rwanda National Police, and other law enforcement agencies, such as the DASSO and the Inkeragutabara, responsible for extrajudicial executions, including officers who may bear command responsibility, and any civilian authorities who are implicated in the killings and may bear responsibility;

- Ensure that all criminal suspects are lawfully detained in recognized places of detention, have prompt access to a lawyer, and are brought promptly after their arrest before an independent judge. If there is credible evidence against the accused, they should be promptly charged with an offense and prosecuted in fair, credible trials or else released;

- Pending disciplinary action or criminal prosecution, suspend with pay officers suspected to be implicated in extrajudicial executions, including those from the Rwanda Defence Force, the Rwanda National Police, and other law enforcement agencies, such as the DASSO and the Inkeragutabara. Those found to be implicated in extrajudicial executions should be removed from their posts in addition to any other criminal sanctions imposed by an independent tribunal;

- Publicly reiterate to officers of the Rwanda Defence Force, the Rwanda National Police, and other law enforcement agencies, such as the DASSO and the Inkeragutabara, that they have an obligation to protect the lives of all persons in Rwanda. Ensure that officers have been trained in and adhere to international human rights law, in particular the rights to life, bodily integrity, liberty, security, and fair trial. The Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, that provide authoritative guidance on international legal standards in this regard, prohibit law enforcement officials from using intentional lethal force except when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life;

- Ensure that all security agents, members of the judiciary, and administrative officials fully respect the right of all Rwandans to the presumption of innocence;

- Ensure that the domestic legal system provides for the conduct of prompt, thorough and effective investigations in line with the standards in the Revised United Nations Manual on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extralegal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions (the Minnesota Protocol).

To Rwanda’s International Donors and Other Governments

- Publicly and privately urge the Rwandan government to take concrete steps to investigate, arrest, and prosecute those responsible for extrajudicial killings described in this report, including those bearing command responsibility. Monitor the progress of these steps regularly;

- Publicly and privately denounce extrajudicial killings committed by any member of the military or law enforcement;

- Ensure support to Rwanda’s security forces—including training, logistics, and other material support—does not go to units or commanders who are implicated in extrajudicial executions and ensure that human rights training and support to investigations and prosecutions of security agent abuses are central components of reform efforts.

To the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions

- Request a formal visit to Rwanda to investigate cases outlined in this report

and others.

To the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

- In accordance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, conduct an immediate investigation into the cases outlined in this report and others;

- Urge the government of Rwanda to attend the forthcoming 61st ordinary session of the African Commission to ensure consideration of its combined 11th, 12th and 13th periodic report as well as consideration of the cases outlined in this report.

To the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations

- Carefully vet officers and personnel from the Rwanda Defence Force and the Rwanda National Police currently serving in United Nations peacekeeping missions to ensure none are implicated in extrajudicial executions in Rwanda;

- Repatriate from United Nations peacekeeping missions any Rwandan soldier, police, or other personnel found to be implicated in extrajudicial executions

in Rwanda.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in Rwanda between January and July 2017. Human Rights Watch interviewed 119 witnesses to the killings, family members and friends of victims, government officials, and others knowledgeable about the arrests and executions. The names of victims are provided throughout this report. However, for security reasons, the names of witnesses and relatives interviewed by Human Rights Watch are not included in the report, and other identifying information has also been withheld.

Some initial interviews were conducted over the phone. These interviews were followed up in person between March and June. Most interviews were conducted in Musanze, Rubavu and Rutsiro districts, in Kinyarwanda with an interpreter. All interviews were conducted individually and privately. Human Rights Watch explained to each interviewee the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, the way in which the interview would be used, and the fact that no compensation would be provided.

Human Rights Watch wrote the minister of justice, with copies delivered to the minister of defense, the minister of local government, and the national police commander, with an overview of Human Rights Watch’s research findings and the details of specific cases documented in this report (see Appendices I, II, III, and IV). Human Rights Watch received no response to its request for a meeting to discuss these research findings or to specific questions about the government’s response to the violations documented here. In July, Human Rights Watch met with five local authorities in Rubavu and Rutsiro districts. Their response is reflected in section III.

This report focuses specifically on extrajudicial executions and other violations in Rubavu and Rutsiro districts, in Western Province, between April 2016 and April 2017. Human Rights Watch has received credible reports of additional cases that allegedly occurred closer to the publication of this report, as well as cases in other areas of Rwanda, including Musanze district, in Northern Province, and Rusizi district, in Western Province. Human Rights Watch is working to confirm these cases, and they are not covered in this report.

I.Background

Since the genocide that devastated the country and claimed more than half a million lives in 1994, Rwanda has made great strides in rebuilding its infrastructure, developing its economy, and delivering public services. But civil and political rights remain severely curtailed, and freedom of expression is tightly restricted.

The death penalty was outlawed in Rwanda in 2007. Before that, it was used sparingly by the state. The death penalty was carried out in connection with genocide trials in 1998 when 22 people were publicly executed, many after summary trials and some without legal assistance.[1]

Extrajudicial killings, that is the killing of a person by governmental authorities without the sanction of any judicial proceeding or legal process, also occurred. For example, in November 2006, police shot and killed three men suspected of killing a gacaca judge[2] the evening of their arrest.[3] In 2007, Human Rights Watch published a report on police killings of at least 20 detainees, many of which appeared to have been extrajudicial executions.[4] In its annual report on Human Rights Practices in Rwanda, the US State Department expressed concern about the killings of five members of the Muslim community in 2016.[5]

Attacks on political dissenters have also occurred, both inside and outside of the country. Since 1996 some Rwandans have been killed outside of the country after they criticized the Rwandan government, the ruling party, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, or President Paul Kagame.[6] Others were murdered, attacked, threatened, or died in unclear circumstances inside the country.[7]

Civilians have also been held unlawfully in unofficial detention centers, including in military custody. In 2014, Human Rights Watch documented how at least 23 people were detained incommunicado for several weeks at Camp Kami, a military camp on the outskirts of Kigali.[8] The detainees were later tried by a civilian court for security-related offenses and alleged collaboration with armed groups. A court in Rubavu acquitted some of them and ordered their release. Some former detainees told Human Rights Watch they were tortured while held at Kami.[9]

Human Rights Watch has also documented a broader pattern of human rights violations against poor people, including petty criminals. Over the years, many such people have been unlawfully detained in so-called “transit centers,” where they faced beatings and other forms of ill-treatment.[10] Human Rights Watch documented the death of one individual just after leaving one such transit center, in Gikondo, Kigali, and received information about similar cases in Mudende transit center, in Rubavu district. Most officials involved in such violations, mainly police, have enjoyed absolute impunity.[11]

II.Extrajudicial Executions

The conduct of members of the Rwandan military, police and other state security actors in northwestern Rwanda has been as ruthless as it has been illegal. Human Rights Watch has documented 37 extrajudicial executions of suspected petty offenders in Rutsiro and Rubavu districts between July 2016 and March 2017, two of whom were women.[12] Human Rights Watch has also documented four enforced disappearances, between April and December 2016, and two cases of individuals who were beaten to death by local residents acting on the encouragement of local authorities, in August 2016 and April 2017. The victims included suspected thieves, smugglers, and people caught or accused of using illegal fishing nets. Some of the family members and friends of victims admitted that the victims had been involved in petty crimes, while others said they were innocent and had been wrongly accused. The killings and enforced disappearances appear to have been part of a broader strategy to spread fear, enforce order, and deter any resistance to government orders or policies.

Government Strategy

Over 40 people interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they had participated in community meetings in Rubavu and Rutsiro districts where military officers or local government officials declared that thieves would be arrested and killed. Local authorities in Rwanda, including law enforcement officials, hold regular community meetings at the village, cell, and sector level. These meetings in general are not mandatory, but several residents told Human Rights Watch they felt pressured to attend. The meetings are not on a fixed schedule, but there is at least one per month after umuganda, mandatory community work held the last Saturday of every month. Participation at the meeting after umuganda is obligatory. Some of these local meetings were called after residents had complained about the high crime rate in their villages.

Several people told Human Rights Watch that they thought a “law” had been adopted stipulating that all thieves and other criminals would be killed, referring to multiple statements made by military and local government officials about the killings of petty criminals.

These warnings at local meetings that authorities would no longer tolerate illegal activity—such as theft, fishing with illegal nets, or smuggling goods across the border—began in early 2016. The cases documented by Human Rights Watch of extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances of suspected petty offenders by the Rwanda Defence Forces, the Rwanda National Police, DASSO[13], and the Inkeragutabara[14] began in April 2016.

One resident from the Kavolo cell[15] in Rubavu district told Human Rights Watch that local authorities delivered warnings in routine meetings: “In 2016, the authorities started saying things in meetings like, ‘We will kill people we catch stealing.’ It was usually the military officers who said this at cell and sector meetings.”[16]

On April 26, 2017, Major General Alexis Kagame, the military commander of the third division, which covers the Western Province, participated in a public meeting in Gisenyi in which he said that people who illegally crossed the border between Rwanda and Congo fell into three categories: those who smuggle goods into the country and want to avoid tax, thus robbing the country of its development; those who smuggle drugs into the country and want to kill the youth; and those who have links to the FDLR (the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, a largely Rwandan Hutu armed group, based in eastern Congo) and wish to destabilize the country.[17] Kagame said that people in these groups were “enemies of the country” and he called on citizens to protect the country from these enemies. Kagame promised close collaboration between the population and the army to safeguard security.[18] The mayor of Rubavu district, Jeremie Sinamenye, also participated in the meeting.

A participant at another public meeting on November 1, 2016, in Karongi district, organized by the Rwanda Governance Board and attended by many local leaders from the Western Province, told Human Rights Watch that Kagame said that all thieves would be killed.[19]

A resident of the Rukoko cell in Rubavu district, near the border with Congo, described how soldiers stood up “without fear” during village meetings, telling local residents: “We will kill anyone who crosses the border illegally.” The civilian authorities “just agree,” he added; “they can’t contradict the military.”[20]

Some witnesses spoke of lists that local officials established to identify those who should be killed. Two residents of Munanira cell, Rubavu district, told Human Rights Watch that military and civilian authorities organized a meeting in their village four days before the execution of Innocent Nshimiyimana, who was killed in neighboring Kiraga cell. The officer in charge of the local military post at that time said during the meeting, “Every thief has to be shot,” according to one of the witnesses.[21] The officer also said that the security services had established a list of all thieves to be eliminated, according to the other witness.[22] A resident of Nyabirasi sector, Rutsiro district, who saw the bodies of Jean de Dieu Habiyaremye and Pierre Hakizimana—two suspected thieves killed by security forces in November 2016—said he saw soldiers with a list that they showed to village leaders to tell them which individuals should be targeted.[23]

A resident of Kanama sector in Rubavu district told Human Rights Watch: “During meetings in our region, the authorities said that the thieves will be killed. I was then afraid that I could be beaten because I’m a family member of [one of the victims].” The resident added that, in February 2017, a meeting was organized in his village by military and local government officials. The officials ordered all thieves to come forward and ask for clemency, and then said: “If you steal again, we will kill you.” Several people who were apparently innocent stood up and asked for pardon, in fear of being killed if they did not do so, the witness said.[24]

Along the shores of Lake Kivu, similar warnings have been made about the use of illegal fishing nets (known in Kinyarwanda as kaningini). One resident of Bushaka cell in Rutsiro district told Human Rights Watch, “In local meetings, the authorities tell us to turn in local thieves. But they also talk about the [fishing] nets. They say the kaningini are not allowed. They say those caught with this net will be dealt with by the authorities.”[25] Another resident from Bushaka cell said that the authorities’ warnings about the nets have become more serious since 2016. “Before they told us not to use them and that we would be fined if we did,” he said. “But now, the authorities tell us during the meetings: ‘Whoever is caught with a kaningini net will have problems with us.’”[26] Another witness to a meeting in Bushaka cell told Human Rights Watch, “The soldiers told us at one meeting in 2016, ‘You have been thieves for a long time now. We forbid you from going into the lake with these nets. You want to steal all of our fish for yourselves? If you refuse to listen to us we will kill you.”[27] The kaningini net has smaller holes than a legal net and can catch more fish. However, it can also catch young fish and therefore contributes to diminishing the fish stock, which is why it is considered illegal.

In some cases, local military or civilian officials accused the victims of collaborating with or sharing intelligence with the FDLR. A participant in a community meeting in Mutovu cell in Rubavu district told Human Rights Watch that a local government official had said that everyone who goes to Congo without passing through the regular border crossing would be killed, and that there is a high probability they would have gone to Congo to collaborate with the FDLR.[28] Other witnesses told Human Rights Watch about community meetings where residents were accused of sending their children to Congo to join the rebels.[29]

Extrajudicial executions were also used after the fact to serve as a warning to community members. In most of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, local military and civilian authorities told residents after the execution, often during public meetings, that the suspected petty offender had been killed and that all other thieves and other criminals in the region would be arrested and executed.

On the same day as Emmanuel Nzitakuze’s funeral in Tangabo cell in Rutsiro district, local security and civilian authorities held a community meeting. Soldiers had killed Nzitakuze after accusing him of stealing a motorcycle on January 11, 2017. The meeting was held near the place where Nzitakuze was killed in neighboring Haniro cell, and a police officer leading the meeting described the killing as an example of what could happen when people steal, according to a witness. Residents present at the meeting told Human Rights Watch that they were not aware that Nzitakuze was a thief, as it was the first time they heard he had stolen anything. But, one witness said, “the military authority is very strong. You cannot criticize anything in front of the military.”[30]

A resident of Busuku cell in Rutsiro district told Human Rights Watch that authorities often cite the execution of François Buhagarike, who was killed between October 19 and 20, 2016. “The authorities talk about his case in meetings. They say, ‘Someone who supports thieves will also have problems with us. Those caught stealing will be killed, like François. To anyone who knew François, if you steal, you will also be killed.’ All this was said by the military so it must be taken seriously. At the meetings, they intimidate us. They say, ‘We have guns and bullets, not stones.’”[31]

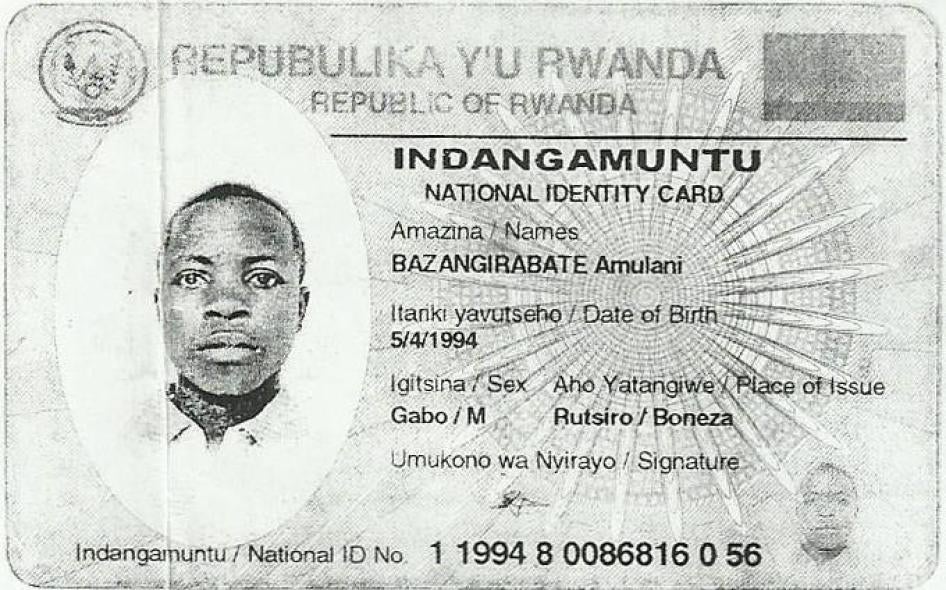

Approximately one week after the killing of Amulani Bazangirabate, who had been accused of using illegal fishing nets, the head of the Bushaka cell held a meeting with local residents at his office. According to a participant at the meeting, he told those gathered that “people should not go out in the water at night alone,” and that “all fishermen need to be in associations in order to use correct nets. For example, Amulani and these other students were fishing illegally. They were killed because they used an illegal net.”[32]

In most of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the victims were immediately buried by their families, without any medical examination. Several family members told Human Rights Watch that government officials forced them to do so. In some cases, police or family members brought bodies to a nearby hospital. An autopsy was conducted in a few cases, but family members received no information about the results and questioned the independence of the medical staff.

In many cases documented by Human Rights Watch, local civilian authorities were also involved in the extrajudicial executions, by alerting the military about suspected thieves, accompanying the police or military during the arrests of the victims, or by publicly expressing support for the killings. In one case, however, a village leader publicly opposed beatings by the military. The military responded that he should not have called them to intervene if he did not want the thief executed. They then shot and killed the victim, in front of the village leader. In the same case, the executive secretary of the sector also questioned the killings by the military. He lost his job a few days later. It is unclear whether this was related to his opposition to the extralegal execution; many local officials in the Western Province lost their job during the period covered by this report.

Extrajudicial Executions

Following is a selection of accounts from witnesses and people close to the victims killed by state security forces in Rubavu and Rutsiro districts. For a list of all the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, including the names of victims, the date and location of the extralegal execution, the security force responsible, and the offense the victim was accused of, see Appendix I. Details on the cases of enforced disappearances and individuals who were killed by local residents acting on encouragement from local authorities are included separately in Appendices II and III.

Jean Damascène Ntiriburakaryo, killed July 30, 2016

Ntiriburakaryo, approximately 44-years-old, was beaten to death by soldiers in Bubaji village, in Rubavu district, after missing umuganda, or mandatory community work. Ntiriburakaryo had stayed home to slaughter a goat. A resident of Bubaji told Human Rights Watch that when he and others heard that Ntiriburakaryo had been killed, they went to his home. As they arrived, they encountered the soldiers who had killed Ntiriburakaryo. “One of the officers showed regret for having killed Jean,” he said. “But he said they had no choice but to beat him seriously because he was against the state’s programs. He said: ‘This will give you a good example to never rebel against the state.’”[33]

Jean Kanyesoko, killed August 2, 2016

Soldiers killed Kanyesoko, 64 and a father of five, after he was caught stealing sugar cane near Kinihera village in Rubavu district. A family member of Kanyesoko said, “Because of poverty he would steal things. He would sometime steal people’s crops.”[34]

A guard at the sugar cane field captured Kanyesoko and called soldiers stationed nearby, who shot him dead. The soldiers later called Kanyesoko’s neighbors to come and take away his body. One friend described what they saw when they arrived:

A soldier was standing next to his body. He said they caught him red-handed. He said, “The order to kill thieves has been given; take his body away and bury him.” Military officers continue to talk about him in cell and sector meetings. They say, “Those caught stealing will be killed like Jean.” I can’t go to meetings now because of this talk of killing criminals. They should just have put this old man in prison.[35]

Innocent Mbarushimana, killed October 11, 2016

Mbarushimana, 20, was accused of stealing several bananas in Kabeza village in Rubavu district. A resident told Human Rights Watch what happened: “I heard people yelling that Innocent was arrested by the military and the Inkeragutabara. They were marching him through the village and saying that he had stolen bananas. A lot of people from the village were there watching, so I tried to go see what was going on. I heard that a decision was made to send Innocent to the sector office so they could investigate. But then I heard shots. Kids then came running and they said that Innocent had been killed.”[36]

Another resident of Kabeza told Human Rights Watch that he tried to follow Mbarushimana to the sector office, but he was chased away by the soldiers. He said he was nearby when he heard the shots and that kids came running and said they saw an Inkeragutabara shoot him.[37]

A third resident of Kabeza also tried to follow Mbarushimana when he was taken to the sector office, but he too was pushed away. He told Human Rights Watch that a child he knows came running after the shots were fired and said, “A soldier gave his gun to an Inkeragutabara and he shot Innocent in the head.”[38]

Four residents of Kabeza who later saw Mbarushimana’s body told Human Rights Watch that he had been shot in the back of the head.

Pierre Hakizimana, killed November 28, 2016

Hakizimana, 35 and the father of five, guarded cows in Rutsiro and Rubavu districts. A local authority in Busuku cell in Rutsiro district accused him of being a thief, and soldiers then arrested him. People close to Hakizimana were told that he was detained at the cell office, so they went to visit him there the next day.

One of them told Human Rights Watch what happened when they arrived:

There were 10 of us, members of the family and neighbors. As we approached Busuku, villagers told us that they had seen soldiers take [Hakizimana] to a nearby tea field, so we went in that direction. When we arrived, we saw soldiers standing around Pierre’s body. One of them said, “Take the body and leave.” When we got to his body, I wanted to cry. But the soldier told us, “Do not cry for a thief.” I was sad and shocked; they would not even let the family mourn... A few weeks after Pierre’s death there was a meeting and the soldiers said, “All thieves will be killed. Look at what happened to Pierre.”[41]

Jovan Karasankima, killed between November 28 and 29, 2016

Karasankima, 40 and the father of three, was accused of stealing a sheep and a lamb in Kavumu village in Rutsiro district. Local authorities and the Inkeragutabara caught Karasankima. The authorities told someone close to him that he would be brought to the police. However, members of the Inkeragutabara instead beat him to death. Witnesses who saw the body told Human Rights Watch that he had been beaten all over his body.[39]

Someone close to Karasankima went to the police in Kavumu and asked why no case had been opened against the killers. He said, “The police told me he was killed by the Inkeragutabara on the orders of the authorities of the cell. He said an order was given to kill thieves and then he told me to go away.”[40]

Fulgence Rukundo, killed December 6, 2016

Rukundo, approximately 28 and the father of two, was detained by a local government official and six soldiers at his home in Munanira village in Rubavu district in the early morning of December 6. Witnesses to his arrest said he was questioned about a stolen cow. Rukundo did not resist arrest and was told he needed to show the authorities where another man accused of the same crime lived.[42]

Later that morning a witness said he saw Rukundo walking towards the BRALIRWA brewery near the lake, where a meeting was taking place, carrying the carcass of a dead cow:

He had his hands tied in front of him and he had this cow carcass on his back and on his arms. The cow’s head was on his own head. Six soldiers told him to walk and there were maybe a hundred villagers following. I followed too. They took him to a primary school near the brewery where a meeting with the mayor of Rubavu had already started. The mayor was talking about the problem of thieves, and when we arrived the meeting turned to Fulgence.

The mayor said that Fulgence had killed another person's cow. Fulgence denied it but he was not allowed to speak. He was just yelling, “I’m innocent!” But the soldiers next to him shouted, “No, you are a thief!” The mayor agreed with the soldiers. The mayor and the soldiers started to write on a piece of paper and then they each signed it. The mayor then announced, “This paper declares that thieves caught will be killed directly.” Some people applauded this; others asked for Fulgence to be forgiven. But the mayor said, “All thieves must be killed.” He said it was an order.

When the meeting was finished, the soldiers walked Fulgence to a small field near a banana plantation. We tried to follow, but the soldiers told us to stay away. There were many of us following; some were primary students. We wanted to see what would happen.

I heard Fulgence say, “I’m tired,” and the soldiers told him to sit down. They untied his hands and they took the cow carcass off of him… A soldier told him to stand up and walk and another soldier told us to leave. At that moment, I heard three shots. The soldiers then yelled at us to leave and we were scared so we ran.[43]

Rukundo’s body was later taken to the morgue in Gisenyi.

Thaddée Uwintwali, killed December 13, 2016

In the evening of December 13, five soldiers arrived at the home of Uwintwali, a farmer in Murambi village in Rutsiro district. An individual close to Uwintwali said they knocked on the door and summoned him outside into the courtyard where they questioned him about a stolen goat and then started to beat him. The soldiers then took him away.

Friends and family started to look for Uwintwali early the next morning. Someone close to the family told Human Rights Watch, “We went over [to Uwintwali’s house] first thing the next morning. We were mobilizing to look for him when a man came and said he saw the body on the road about a twenty-minute walk away. We went there and found Thaddée’s body. He had been shot through the chest.”[44]

Two weeks after Uwintwali was killed, soldiers announced at a Boneza sector meeting: “If someone is caught stealing they are going to have a problem with us.”[45]

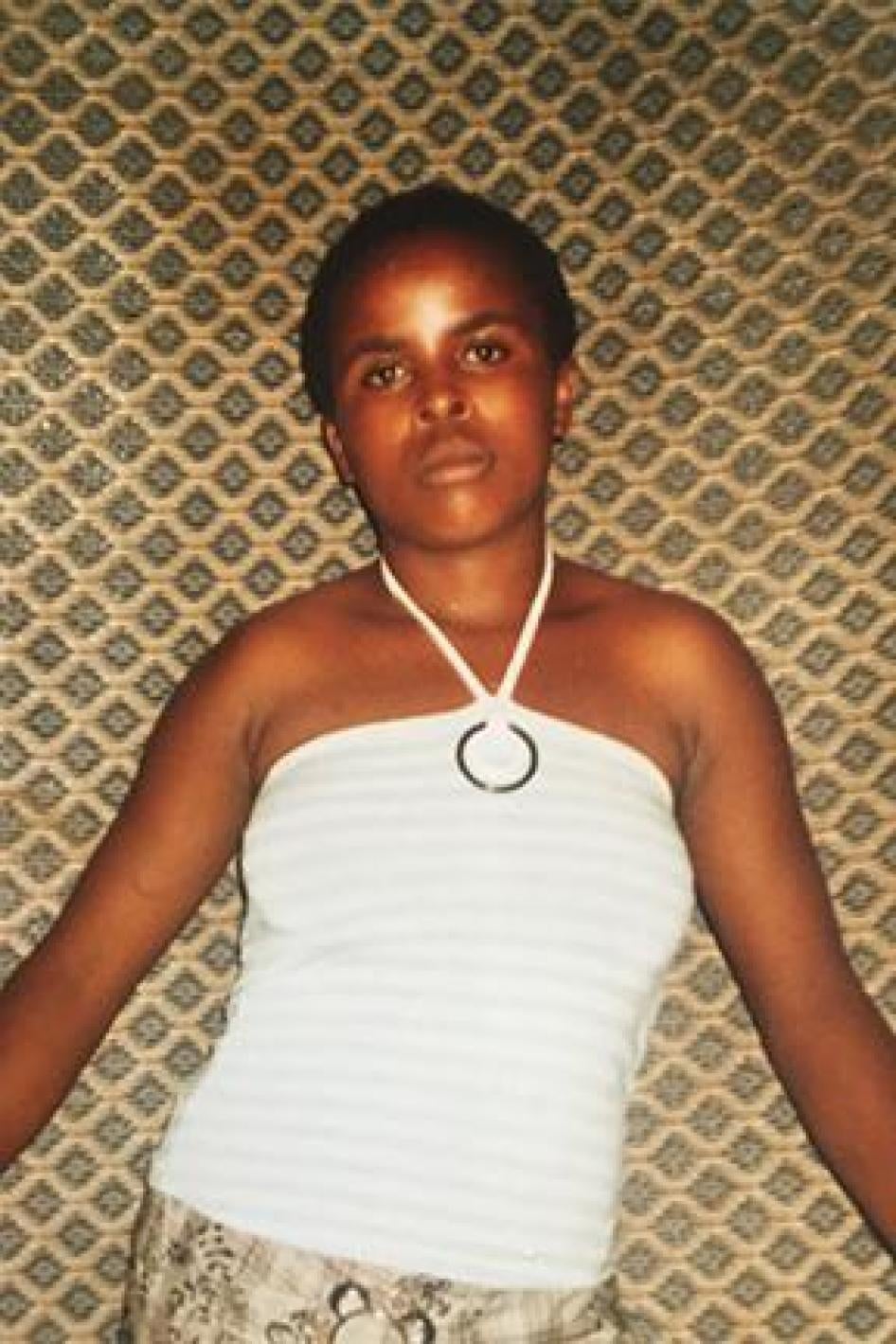

Jeannine Mukeshimana and Benjamin Niyonzima, killed December 16, 2016

Residents of Bisizi told Human Rights Watch they heard shots in the valley near the border with Congo in the evening of December 16. The next day, local authorities told residents to go to the border to identify the bodies. Someone close to Mukeshimana told Human Rights Watch what happened next: “When I arrived, I saw many soldiers standing around the bodies. One soldier said, ‘Look! But no photos! Let this be an example for you that those who travel across the border illegally will be killed like this. These people were transporting marijuana.’ I saw Jeannine among the bodies. I was traumatized.”[47]

Another resident told Human Rights Watch, “We went to see the five bodies. Jeannine had been shot in the head. The message from the military was clear. They said she was smuggling marijuana and that this should be an example for the village.”[48]

The same night soldiers went to Niyonzima’s home village, Kanembwe, and told the village chief in front of several residents that they had killed Niyonzima because he was smuggling marijuana.[49]

Emmanuel Niyigena, killed January 25, 2017

A month after Mukeshimana and Niyonzima (above) were killed, 25-year-old Niyigena was killed in the same area. The bricklayer was arrested and then killed by soldiers as he came back from Congo. A witness to his arrest told Human Rights Watch: “When we had crossed the border from Congo and after we walked 50 meters inside Rwanda, we ran into four Rwandan soldiers. They stopped us, took Emmanuel and went with him into the bush. A few minutes later, we heard several gunshots. They had killed him.”[50] Several other witnesses told Human Rights Watch that his face had been destroyed by multiple bullets. Soldiers later told the family that they suspected him of smuggling drugs.

Executions of Fishermen Using Illegal Fishing Nets

Human Rights Watch documented the killings of 11 fishermen on or near Lake Kivu in Bushaka and Gabiro cells in Rutsiro district and in Rubona cell in Rubavu district. According to family members, friends, and other community members, the victims were all killed because they had used illegal fishing nets, known as kaningini. The kaningini net has smaller holes than a legal net and can catch more fish. However, it can also catch young fish and therefore contributes to diminishing the fish stock, which is why it is considered illegal.

Local authorities, including military and police officers, had warned residents for several years that it was illegal to use these nets, but by 2016 the warnings turned to threats. A fisherman who uses a kaningini told Human Rights Watch, “In meetings the authorities would say, ‘Don’t use the kaningini.’ Then in 2016 they started to say, ‘We are tired of this. Whoever is caught will now have problems with us.’ But because of poverty we have no choice but to keep using the nets.”[51]

The executions on Lake Kivu all happened at night when the victims were fishing from canoes. Several of the victims were fishing with other men, who survived the killings by jumping into the water.

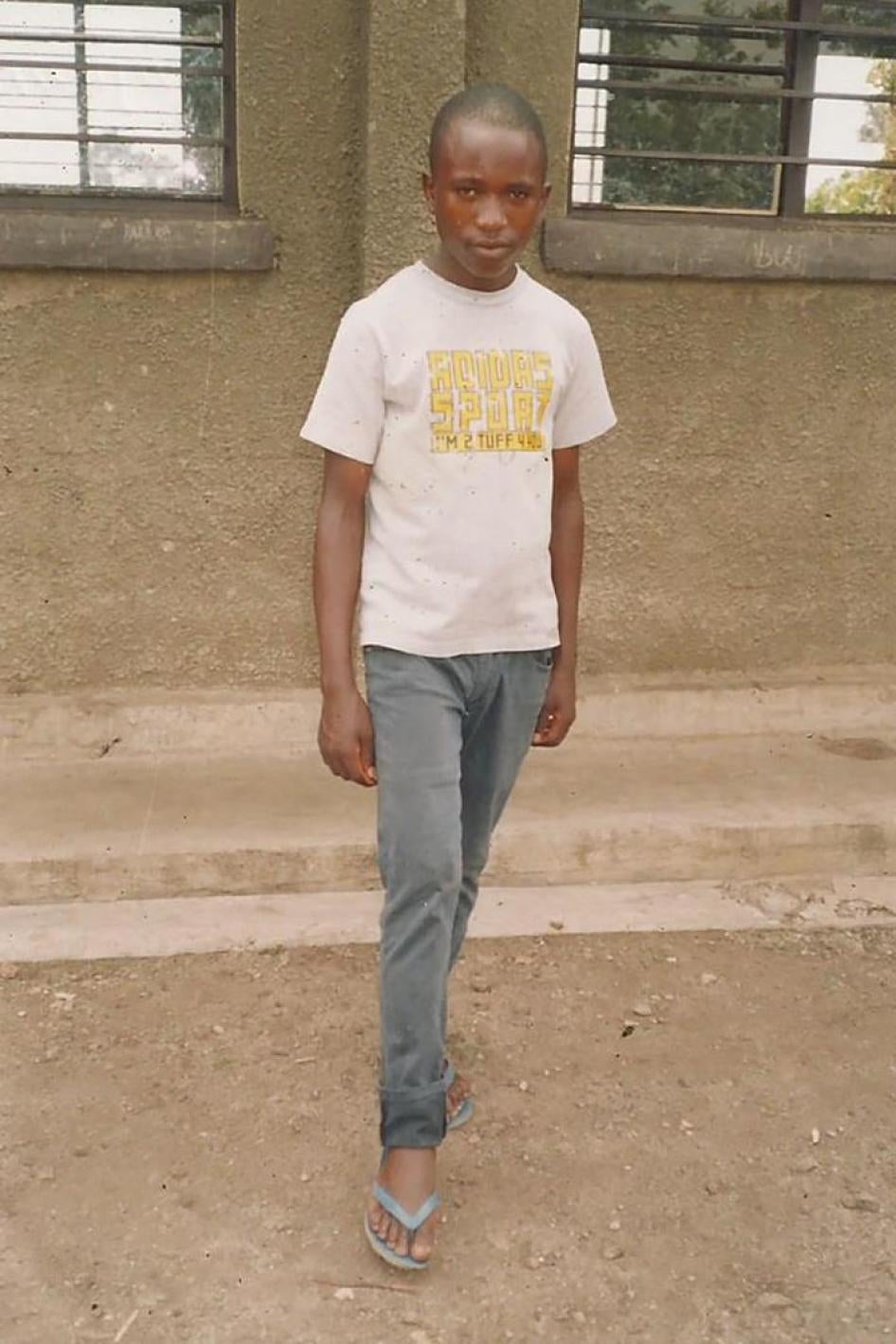

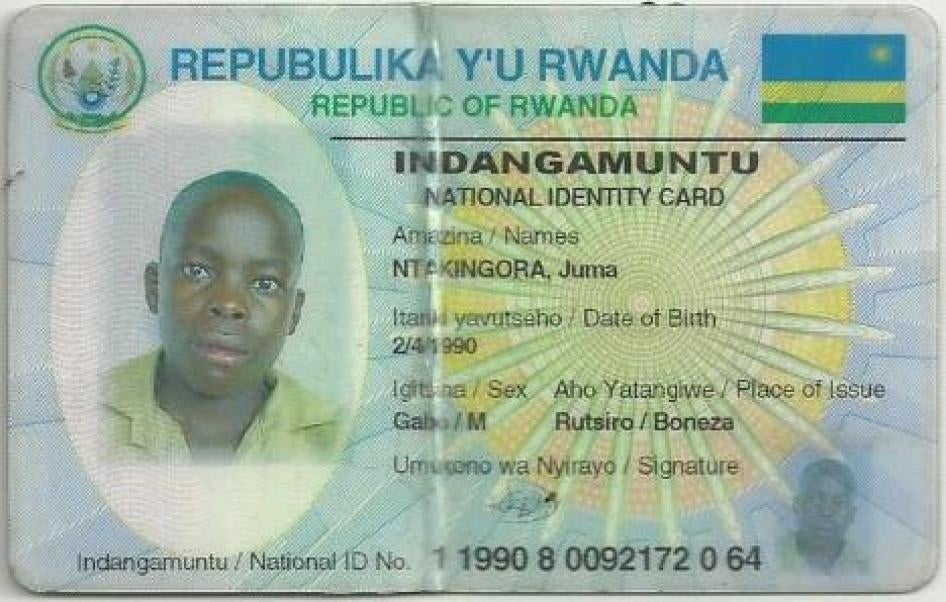

Juma Ntakingora, 26, was killed on September 21, 2016, while fishing near Bugarura village in Bushaka cell. Someone close to Ntakingora told Human Rights Watch: “He was fishing with a friend who later came and told us that they had been attacked by the military patrol boat, that it just came upon them and the soldiers started shooting. We went down to the lake the next day and found his body. He was still in the canoe; it was along the shore. Juma had been shot in the stomach.”[52]

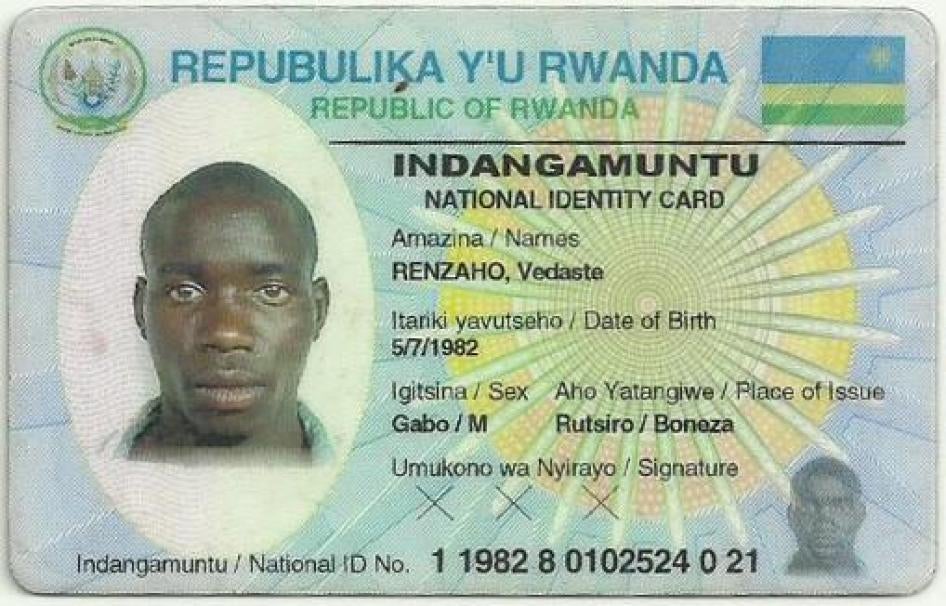

Vedaste Renzaho, 34, was killed in late December 2016 while fishing. He was with another man, who survived the attack and later told Human Rights Watch:

We had been fishing for about two hours when we heard the motor of a military boat. Then we saw its lights. I said to Vedaste, “If you see a boat like that at night, it is looking for us; we should go back in.” But he said, “No, don’t be afraid. They won’t find us.” But when the boat got closer, I decided it was too dangerous. Vedaste could not swim. I said, “Ok, you stay in the boat.” Because I’m a good swimmer, I jumped into the water. I hoped that they would just take the net. I watched from a distance as the soldiers approached the boat. I heard one of them say to Vedaste, “Where is the other guy?” He said, “He jumped into the water.”… They looked at the net and asked why he used it. Then they shot him. They then took a big light and started looking for me, but I swam away.[53]

Local residents found Renzaho’s body the next day, in his canoe along the shore. He had been shot in the stomach.

Alexandre Bemeriki, a fisherman and father of four, was killed in October 2016 after soldiers found kaningini at his home. Someone close to Bemeriki told Human Rights Watch, “Soldiers went to his house around 9 p.m. and took him outside. I saw them put his hands behind his back. They started to beat him and told him to bring out his fishing net.

He was asking forgiveness… The next day we heard that there was a body down near the lake. We went to look and we found Bemeriki’s body. He had been shot in the chest.”[54]

The village chief who was there when the body was discovered told Bemeriki’s family members, “You are poor and you can’t pay for an autopsy. So because you are poor, just bury him.”[55]

As with other cases of extrajudicial executions, local civilian, military, and police authorities were open with community members about the killings and sought to use them as examples. A resident of Bugarura told Human Rights Watch about a meeting organized by the police at the sector office in late December, soon after Amulani Bazangirabate, 22, was shot dead by soldiers:

The police said that people should not go out in the water at night alone and that all fishermen need to be in associations so they use correct nets.

The executive secretary of the Boneza sector then said, “For example Amulani and Nyumagabo[56] could not be allowed to fish illegally. They were killed because they used an illegal net.”[57]

Despite the risks, people continue to use the kaningini. One fisherman told Human Rights Watch, “They say not to use them, but we have no choice. We must eat. People still fish with it because they have no choice.”[58]

|

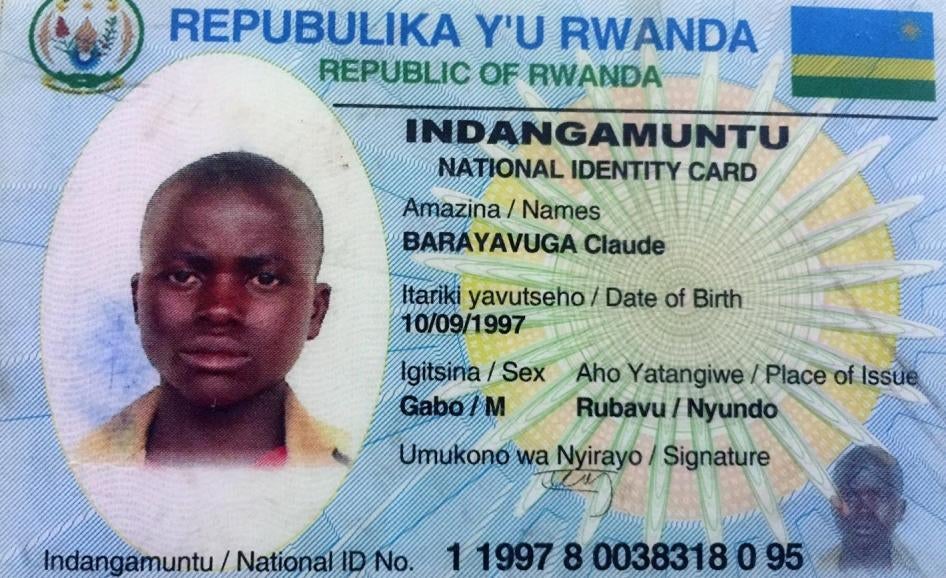

Killed by Civilians after Encouragement from Local Authorities Human Rights Watch documented two cases of men killed by civilians after being told to do so by local authorities.[59] There may be more cases of this nature as Human Right Watch spoke with people who participated in meetings in which this was encouraged. For example, one participant at a meeting in Nyundo sector, Rubavu district, told Human Rights Watch, “The mayor of the district told the population to stop keeping livestock in their homes, but the population said there was Claude Barayavuga, killed April 27, 2017 Barayavuga was a 19-year-old with intellectual disabilities from Bahimba village, Rubavu district. He had a history of stealing in his community. People close to Barayavuga told Human Rights Watch that this was because of his disability. “If he saw sugar cane or maize that was ready to eat, he would take it,” one person said. “He did this because he was sick and he did not really understand that he should not do it. He would steal a lot.”[61] On April 23, the village chief held a meeting and, according to a participant, told local residents: “I have been asked to give a list of criminals and thieves to the cell officials. I know there is one thief, Jean-Claude. If you catch him, kill him.”[62] On April 27, Barayavuga stole two light bulbs from a private citizen who chased him down and beat him to death with a hammer. The police arrested the man suspected of killing Barayavuga, but he was released a few days later. Another resident told Human Rights Watch, “Claude’s death was sanctioned. Just a few days before he was killed, I heard the chief say at a meeting, ‘If Jean-Claude is caught stealing again, kill him.’”[63] On May 3, the executive secretary of Nyundo sector held a meeting in Gatuvo, a commercial center near Bahimba. According to three witnesses, he told residents at the meeting, “the death of Jean-Claude is an example for all thieves.”[64] |

Threats to Family Members

In almost all the extrajudicial killings documented by Human Rights Watch, family members of victims were too afraid to seek justice, despite their right under Rwandan and international law to do so (see section IV). The reason for this was best summed up by the uncle of one victim: “Who could we accuse even if we wanted to? These men are killed by the state, and you can’t accuse the authorities of the state.”[65]

Many family members were threatened when they tried to recover the bodies of their loved ones. The authorities told them not to inquire about what happened, and not to grieve. Some families buried the body in secret, to avoid any reprisals from the authorities. Several families left their villages when their husbands, sons, or brothers were killed, fearing that they could also be targeted.

“They told me they had taken [my husband] to the forest,” a widow told Human Rights Watch. “When we arrived there, we saw the soldiers and then we saw [the body]. The soldiers told us not to be sad and not to cry. They said if we dared to cry, we would risk being shot.”[66]

“Since the killing, our community is very saddened,” a witness to one of the killings told Human Rights Watch. “We decided to keep our mouths shut; we cannot talk about this incident. We have no right to free expression. If we talk about this, we will end up in prison or disappear.”[67]

In a few cases, family members of victims did try to seek justice, but they were discouraged by local authorities. The widow of one victim from Rutsiro district told Human Rights Watch that she sought justice in the village where her husband was killed:

I went to the police, and I asked why there was no case against the man who killed my husband. I was told that an order had been given and I was to go away. They told me he was killed on orders of the authorities of the cell. When the police told me to leave, I knew I had no choice. I wanted [my husband]’s ID but the police said, “No, it’s for us.” Now I don’t dare to return to get it. They scare me… When the police said, “the order was given,” I was so disappointed. But if the police helped to investigate and if I had money for a lawyer, I would file a case against those who killed my husband.[68]

Most family members were simply too scared to inquire into the killings. The widow of one victim told Human Rights Watch, “The things I’ve told you I can’t say to the authorities because I could be killed as well. I live in fear. I don’t understand where this order to kill thieves comes from. But now I wonder if they will decide to kill the widows of men they accused of stealing.”[69]

III.Government Response to Extrajudicial Executions

On July 5, 2017, Human Rights Watch delivered a letter[70] to Johnston Busingye, minister of justice, outlining its research on extrajudicial executions in Rubavu and Rutsiro, highlighting concerns, asking for further information, and requesting a meeting. Copies were also delivered to the ministers of defense and local government and the head of the police. The appendices in this report were attached to the letter. None of these officials responded to Human Rights Watch.

On July 5 and 6, Human Rights Watch met with five local officials from some of the areas where the violations documented in this report took place. The mayor of Rubavu district, Jeremie Sinamenye, told Human Rights Watch that the reports of extrajudicial executions of thieves and drug smugglers in Rubavu were based on false information:

What the people are telling you is not true. We are preparing for elections and in this period, there are many rumors. These lies come from the FDLR and the abacengezi[71] to destabilize the country. This is Habyarimana’s region[72] and there are still people loyal to him in Congo. In Rwanda, we follow the law. If someone is suspected of a crime, they are taken to the police and they will go to court. The military do not participate in the affairs of the population. There is no new law saying that thieves should be killed. There is nothing of the kind. This is all rumors.[73]

The executive secretary of Nyundo sector in Rubavu district, Jean Bosco Tuyishime, told Human Rights Watch he had only been in his post for three months and could not answer questions about the extrajudicial executions and other violations. He said the district mayor’s response to Human Rights Watch also represented his own response.[74]

The executive secretary of Nyamyumba sector in Rubavu district, Elisaphan Ugiriribambino, also told Human Rights Watch that he was new to his post, he was appointed in March 2017, and that he had not heard about the executions of Fulgence Rukondo and Innocent Nshimiyimana. He said, “I do not think the military could kill people here. I think this is lies. There has been no order here in Rubavu to kill thieves.”[75]

The executive secretary of Rukoko cell in Rubavu district, Chantal Mukeshimana, told Human Rights Watch that Ernest Tuyishime, Jeannine Mukeshimana, Benjamin Niyonzima and others were killed by the military while illegally crossing the border. However, she explained that these killings were not because of crimes they had committed or drug smuggling, but because they refused to stop when told to by the soldiers. “Instead they ran,” she told Human Rights Watch. “The military then had no choice but to shoot them; it is a security issue.” Mukeshimana told Human Rights Watch that she is not aware of any order to execute suspected thieves.[76]

Etienne Nirere, the executive secretary of Boneza cell in Rutsiro district, where Human Rights Watch documented the killings of 11 fishermen between September 2016 and March 2017, told Human Rights Watch that while the kaningini nets have been illegal since 2006, nobody had been killed for using them. Human Rights Watch shared its research findings with Nirere, and he suggested that many missing fishermen presumed dead may have left for Lake Victoria, between Uganda and Kenya, for work. When told by Human Rights Watch of testimony indicating the 11 bodies had been found, he said, “Many fishermen drown in the water; the boats can be turned over by waves.” When told of testimony of wounds indicating the fishermen had been shot, Nirere said, “I don’t know about that, but the military and the police do not kill people.”[77] Nirere told Human Rights Watch he was not aware of any order or policy to kill thieves.

IV. National and International Legal Standards

The rights to life, to bodily integrity, liberty and security as well as to due process and a fair trial, including the presumption of innocence, are guaranteed in the Rwandan constitution and international law. According to Rwandan law, a police officer may only use firearms when he or she has unsuccessfully tried other means of force, is subject to violence, or is fighting or arresting armed persons. There did not appear to be any threat to the lives of security personnel or others in any of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch. None of the victims were armed, and there was no evidence that any of the suspects had used violence, either when committing any crime or at the time of arrest.

The Rwandan Constitution

There is no legal basis for executions in Rwanda, judicial or extrajudicial, as the death penalty was abolished in 2007. In the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, no procedures were undertaken to establish the guilt of suspected criminals before executing them and statements and acts by soldiers preceding the killings denied a presumption of innocence.

The executions documented in this report violate several key articles of the constitution:

- Article 12 states that “no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of life.”

- Article 13 states that “a human being is sacred and inviolable [and] the state has an obligation to respect, protect and defend the human being.”

- Article 15 states that “all persons are equal before the law. They are entitled to equal protection of the law.”

- Article 29 states that “everyone has the right to due process of law, which includes the right: (1) to be informed of the nature and cause of charges and the right to defence and legal representation; (2) to be presumed innocent until proven guilty by a competent Court; [and] (3) to appear before a competent Court…”[78]

International Conventions and Standards

International human rights law obligates governments to end impunity for serious human rights violations by undertaking prompt, thorough, and impartial investigations of alleged human rights violations, ensuring that those responsible for serious violations are prosecuted, tried and duly punished, and providing an effective remedy for victims.[79]

Rwanda is a party to a number of international treaties (such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights) that strictly prohibit arbitrary deprivation of life, arbitrary detention, and ill-treatment of detainees, and that also require due process and fair trial. Under those treaties it has assumed legal obligations to deter and prevent gross violations of human rights, and to investigate, prosecute and remedy such violations.[80] This also entails addressing the victims’ rights to justice and reparations.[81]

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) requires that governments adopt measures, including through the legal system, to protect fundamental rights.[82] According to the UN Human Rights Committee, the independent expert body that monitors compliance with the ICCPR, a government’s failure to investigate and bring perpetrators to justice, particularly with respect to crimes such as killings, may itself be a violation of the covenant.[83]

Similarly, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights places obligations on states to ensure protection of charter rights, and for individuals to have rights violations against them heard by competent national institutions.[84]

Various international standards also seek to promote state efforts to obtain justice for victims. For instance, the Principles on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extralegal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions call upon governments to remove officials implicated in such crimes from direct or indirect power over the complainants and witnesses, as well as those conducting the investigation.[85]

Combating impunity requires the identification of the specific perpetrators of the violations. Superiors may also be responsible for the unlawful acts of their subordinates, where the superior had effective control over their subordinates, knew or had reason to know of the unlawful acts, and failed to prevent or punish those acts.[86]

In addition to the obligation to investigate and prosecute, governments have an obligation to provide victims with information about the investigation into the violations.[87] The former UN Commission on Human Rights adopted principles stating that “irrespective of any legal proceedings, victims, their families and relatives have the imprescriptible right to know the truth about the circumstances in which violations took place.”[88]

Under the ICCPR, states also have an obligation “to ensure that any person whose rights or freedoms as herein recognized are violated shall have an effective remedy.”[89] The ICCPR imposes on governments the duty to ensure that any person shall have their right to an effective remedy “determined by competent judicial, administrative or legislative authorities, or by any other competent authority provided for by the legal system of the state, and to develop the possibilities of judicial remedy.”[90] The state is under a continuing obligation to provide an effective remedy; there is no time limit on legal action.[91]

The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials state that “law enforcement officials shall not use firearms against persons except in self-defence or defence of others,” “only when less extreme means are insufficient to achieve these objectives,” and that intentional lethal use of firearms should only happen “when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.”[92]

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by researchers in the Africa Division at Human Rights Watch. Ida Sawyer, Central Africa director, and Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director, edited the report. Aisling Reidy, senior legal advisor, provided legal review. Jean-Sébastien Sépulchre, associate in the Africa division, provided additional editorial assistance. John Emerson provided the maps. Olivia Hunter, Jose Martinez, and Fitzroy Hepkins provided production assistance.

Sarah Leblois translated the report into French. Jean-Sébastien Sépulchre and Peter Huvos, French website editor, vetted the French translation.

Human Rights Watch wishes to thank the family members and friends of victims who spoke with us, sometimes at great personal risk.