Summary

Everyone here in Kigali can be arrested and taken to Kwa Kabuga.

When you spend a day without being arrested, you say God has been good.

−Former detainee in Gikondo Transit Center, Kigali, March 2014

Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, stands out as one of the cleanest and tidiest cities in Africa. In comparison with the period immediately following Rwanda’s genocide in 1994, Kigali today has very few street children and beggars. Sex workers are rarely seen on the streets. Street vendors are always on the lookout for the police and ready to pack up their goods at a moment’s notice.

This positive image of a sparkling and safe city is largely a result of a deliberate practice by the Rwanda National Police of rounding up “undesirable” people and arbitrarily detaining them at Gikondo Transit Center, an unofficial detention center in the Gikondo residential suburb of Kigali. There, they are exposed to human rights abuses, including inhuman and degrading treatment, before being released back onto the streets, often with orders to leave the capital. There is no lawful basis for depriving the majority of Gikondo’s detainees of their liberty, and no judicial process or oversight regulating their detention.

This report, based on research conducted between 2011 and 2015 in Kigali, describes human rights abuses at Gikondo Transit Center, commonly known as Kwa Kabuga. Street children, street vendors, sex workers, homeless people, suspected petty criminals, suspected serious offenders, and others assumed to be from these groups have been detained at Gikondo Transit Center. According to research carried out by Human Rights Watch, the majority of those detained there were poor, homeless or otherwise marginalized or vulnerable people, who were arbitrarily rounded up by the police.

Human Rights Watch research suggests that as many as several thousand people are likely to have passed through the center and have been subjected to ill-treatment over the past ten years; Gikondo has been used as a detention center since at least 2005. This report follows up research carried out by Human Rights Watch nine years ago, the findings of which were published in 2006.

Former detainees at Gikondo told Human Rights Watch that up to 800 people could be held at the center at one time, in several large rooms. Some described up to 400 detainees held in one room.

The length of detention at Gikondo could range from a few days to several months. Human Rights Watch documented cases of detainees held there for as long as nine months. On average, those interviewed by Human Rights Watch had spent around 40 days in the center.

In all of the 57 cases documented by Human Rights Watch, detainees were held at Gikondo without charge and with no regard for due process, in clear violation of Rwandan law.

Ill-treatment and beatings of detainees by the police or by other detainees, acting on the orders or with the assent of the police, are commonplace at Gikondo. Former detainees spoke of routine beatings for actions as trivial as talking too loudly or not standing in line to use the toilet. Forty-one of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were beaten; another seven described witnessing beatings of other detainees.

Contrary to government assertions that the environment at Gikondo was clean and conducive and that detainees were provided with adequate food, sanitary, and recreational facilities, detainees told Human Rights Watch of conditions that could only be described as deplorable and degrading. Detainees were not accorded basic necessities, such as a regular supply and reasonable quantities of food and clean water, and were often held in cramped conditions. Detainees slept on the floor, often without mattresses.

Mattresses, when provided, were shared by several detainees and were often infested with lice and fleas. Some new mattresses were distributed in late 2014 and early 2015, but detainees told Human Rights Watch they were insufficient. Sanitation and hygiene were very poor; as recently as February 2015, detainees were forced to use an open trench as a toilet.

Although labeled as a center for rehabilitation by the government, and allegedly staffed with counselors and healthcare workers, access to medical treatment at Gikondo is sporadic, and rehabilitation support, such as it is needed, is non-existent. Visits by medical professionals are irregular and the little medical care that is provided often fails to address detainees’ needs. HIV positive former detainees told Human Rights Watch of a continuing lack of treatment even once officials had confirmed they had the virus. No particular provisions are made for female detainees’ health and hygiene needs.

Visitors are rarely allowed in Gikondo. Human Rights Watch only met one person who was able to visit a detained relative, and only after negotiating with personal contacts in the police. Lawyers rarely, if ever, visit Gikondo, as most of the detainees there cannot afford a lawyer or do not know how to obtain legal assistance.

Several former detainees described paying members of the police for their release. These payments were usually arranged via a third party, such as a friend or relative.

Until late 2014, children accounted for a significant proportion of detainees in Gikondo. Human Rights Watch met with 13 former detainees under 18 years old, many of whom had been detained at Gikondo several times. The Rwandan Penal Code defines a child as someone under 18, which accords with the definition under regional and international human rights law, such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, to which Rwanda is party. Human Rights Watch also interviewed 10 women who had been detained with their infants and one woman who was six months pregnant during her detention.

In a positive decision in August 2014, the office of the Mayor of Kigali and the National Commission for Children announced that children would no longer be sent to Gikondo. Human Rights Watch has not received reports of new cases of children detained in Gikondo since that time. However, adult men and women continue to be detained there at time of writing.

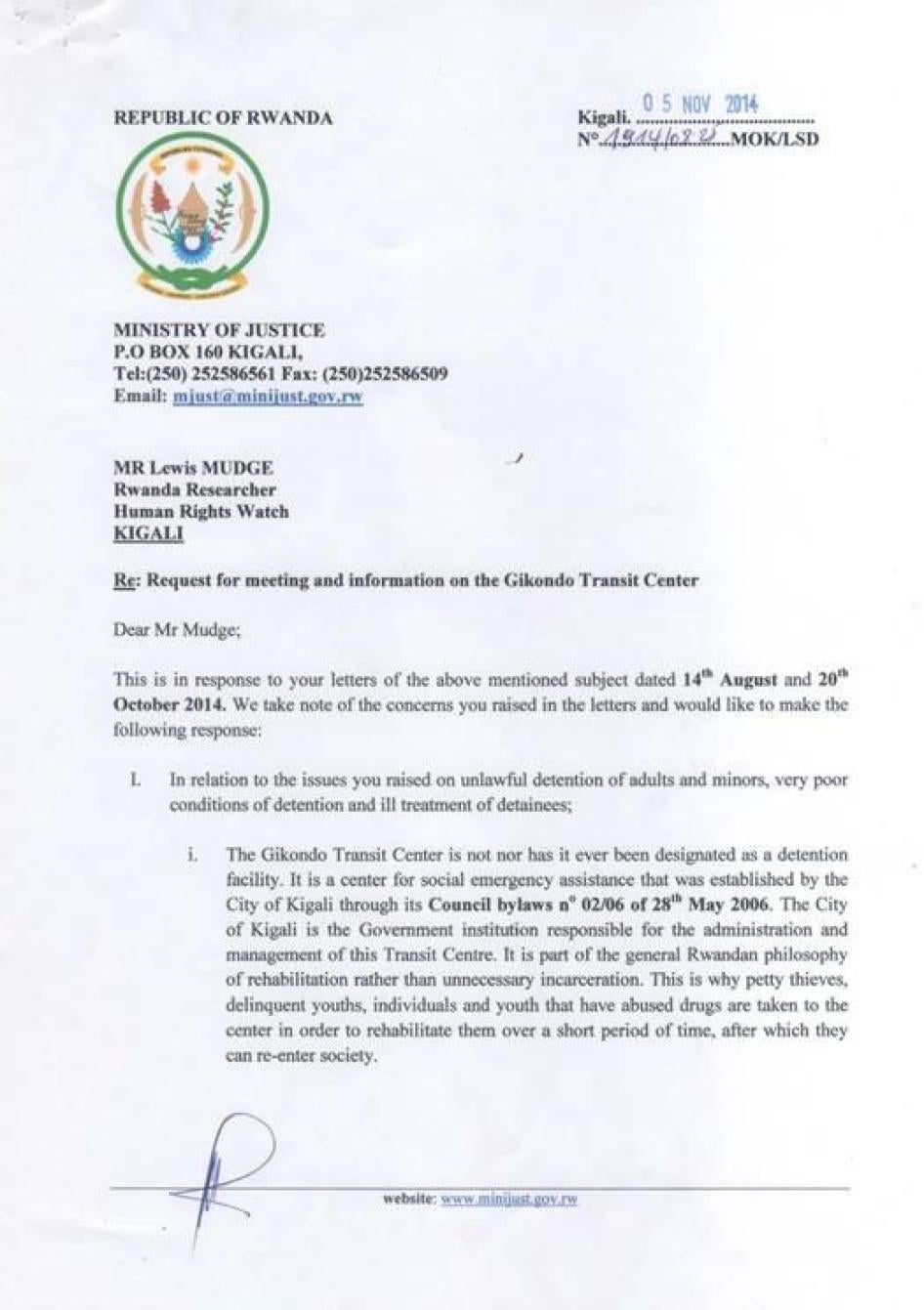

The Rwandan government maintains that Gikondo is not a detention center, but exists to provide rehabilitation in the form of social emergency assistance and acts as a transit point to other rehabilitation centers. The government also refutes allegations of abuses at Gikondo. However, in a letter to Human Rights Watch in November 2014, reproduced in Annex I of this report, the minister of justice noted that there was “currently no legal framework for [the center’s] administration.” The Rwandan government’s response is described in greater detail in Section III.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Rwandan government to immediately close Gikondo Transit Center and release all detainees there, unless they are to be charged with a legitimate criminal offense. Those who are to be charged should be brought promptly before a court and transferred to a recognized detention facility, in compliance with Rwandan law.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Rwanda National Police to stop rounding up vulnerable and economically marginalized people, many of whom end up in Gikondo. The police should investigate cases of unlawful detention, ill-treatment, and corruption such as those described in this report, suspend those responsible for these abuses, and ensure they are brought to justice.

Recommendations

To the Rwandan Government

- Immediately close Gikondo Transit Center and ensure that anyone deprived of their liberty is detained only on grounds explicitly provided for in law and in accordance with full respect for due process rights.

- Ensure that detainees are held only in official, recognized detention facilities, in accordance with Rwandan law.

- Release all detainees at Gikondo unless there is an intent to promptly charge them with a legitimate criminal offense. Adults against whom such charges are intended should be transferred immediately to an official detention center and brought promptly before a court, within the timeframe required by Rwandan law.

- Ensure that any detainee who has already been formally charged with a criminal offense and is awaiting trial is released pending trial in accordance with the law, or, if a court orders pretrial detention, is held in an official detention center and guaranteed a fair trial within a short period.

- Ensure that all child detainees facing criminal charges are tried by juvenile courts and transferred to official rehabilitation centers specifically for juveniles where they can be detained separately from adults. They should be deprived of liberty only in exceptional cases, and for the shortest appropriate period.

- Investigate cases of abuse and misconduct by the police, such as those described in this report, and prosecute officials responsible for the illegal detention and ill-treatment of detainees at Gikondo.

- End the practice of rounding up and detaining street children, street vendors, sex workers, homeless people, and beggars.

- Ensure that training programs for police officers incorporate obligations on respecting human rights of all citizens, including vulnerable groups who may particularly come into contact with law enforcement officials, such as street children, sex workers, drug users, and other disadvantaged people.

- Support economically vulnerable persons through social protection schemes, education, and vocational training.

- Take measures to fight discrimination and stigma against street children, sex workers, vagrants, street vendors, beggars, and other disadvantaged people.

To the Rwanda National Police

- End arbitrary round-ups, arrests, detention, and beatings of street children, sex workers, street vendors, homeless people, beggars, and other disadvantaged people.

- Investigate allegations of unlawful detention, ill-treatment, and corruption such as those described in this report.

- Suspend and take disciplinary action against police officers responsible for these abuses and ensure they are brought to justice.

- Immediately release anyone arbitrarily detained.

- Issue and enforce clear orders to all police prohibiting the extortion of money in exchange for releasing detainees.

To Rwanda’s International Donors and Other Governments

- Call for the immediate closure of Gikondo Transit Center.

- Urge Rwandan authorities to investigate police abuses against street children, sex workers, street vendors, homeless people, beggars, and other disadvantaged and vulnerable groups.

- Urge the Rwandan authorities to bring to justice, in fair and credible trials, members of the Rwanda National Police and other individuals responsible for unlawful detention, ill-treatment, corruption, and other abuses at Gikondo.

- Consider earmarking part of training assistance to the Rwanda National Police for the protection and promotion of the rights of street children, sex workers, street vendors, homeless people, beggars, and other vulnerable groups.

Methodology

This report is based on research carried out by Human Rights Watch in Kigali between 2011 and 2015. Most of the research was conducted in 2014. This work is a continuation of Human Rights Watch’s earlier research on Gikondo: in 2006, Human Rights Watch published a report documenting the harsh conditions in which hundreds of street children and other detainees were held there.

Human Rights Watch staff interviewed 57 former detainees who had been held at Gikondo between 2011 and 2015: 27 men and boys and 30 women and girls. Ten boys and three girls were aged 18 or under at the time they were interviewed; the youngest was 13 years old. Human Rights Watch also interviewed friends and relatives of detainees at Gikondo. Names and other identifying information have been withheld from this report to protect privacy and security.

Human Rights Watch conducted the majority of interviews in Kigali, in Kinyarwanda with an interpreter. Former detainees were interviewed individually and privately. Human Rights Watch staff explained to each interviewee the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, the way in which the information would be used, and the fact that no compensation would be provided.

Human Rights Watch requested authorization to visit Gikondo Transit Center from the mayor of Kigali, most recently on April 29, 2015, but received no response.

In 2014 Human Rights Watch wrote to the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Internal Security, the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion, the Ministry of Youth and ICT, the Ministry of Local Government, the mayor and the vice-mayor of Kigali, and the inspector general of the Rwanda National Police, requesting meetings to discuss its research findings on Gikondo. None of these officials agreed to meet Human Rights Watch. The minister of justice responded to Human Rights Watch’s concerns in writing, in a letter dated November 5, 2014 (see Annex I of this report). In late December 2014, Human Rights Watch met the chief ombudsman to discuss allegations of police corruption in Gikondo.

This report focuses specifically on Gikondo Transit Center. Human Rights Watch has documented abuses in several other transit and detention centers in Rwanda, but this report does not cover those locations.

I. Background

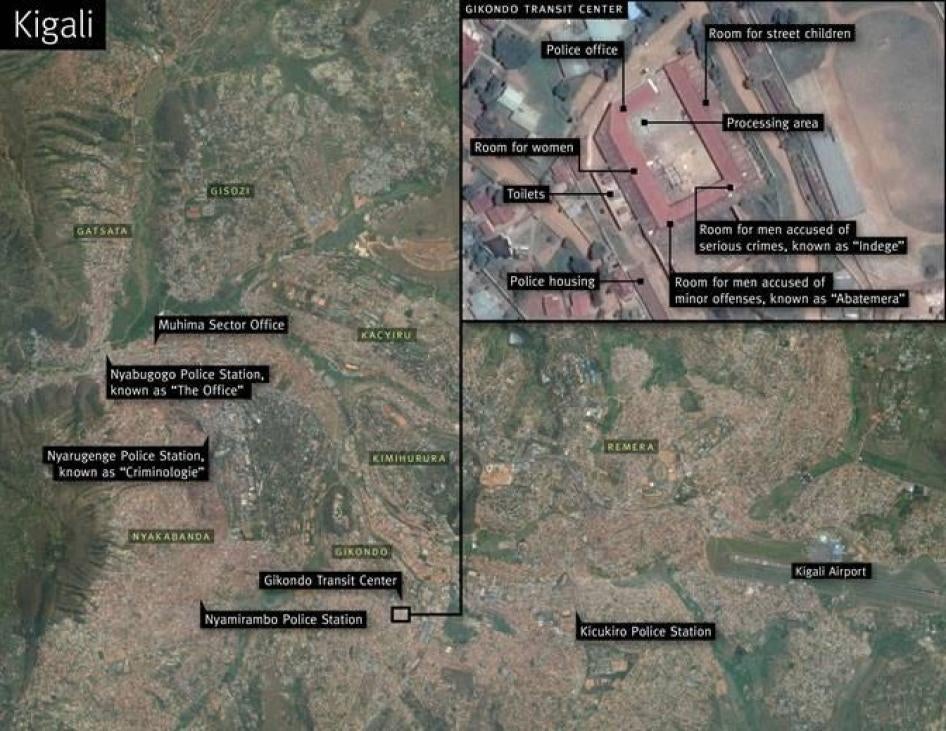

Gikondo Transit Center derives its unofficial name, Kwa Kabuga, from that of Félicien Kabuga, a wealthy businessman alleged to be a chief financier of the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. Kabuga has been indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, but remains at large.[1] The center is located in one of Kabuga’s old factories in the Gikondo neighborhood of Kigali.

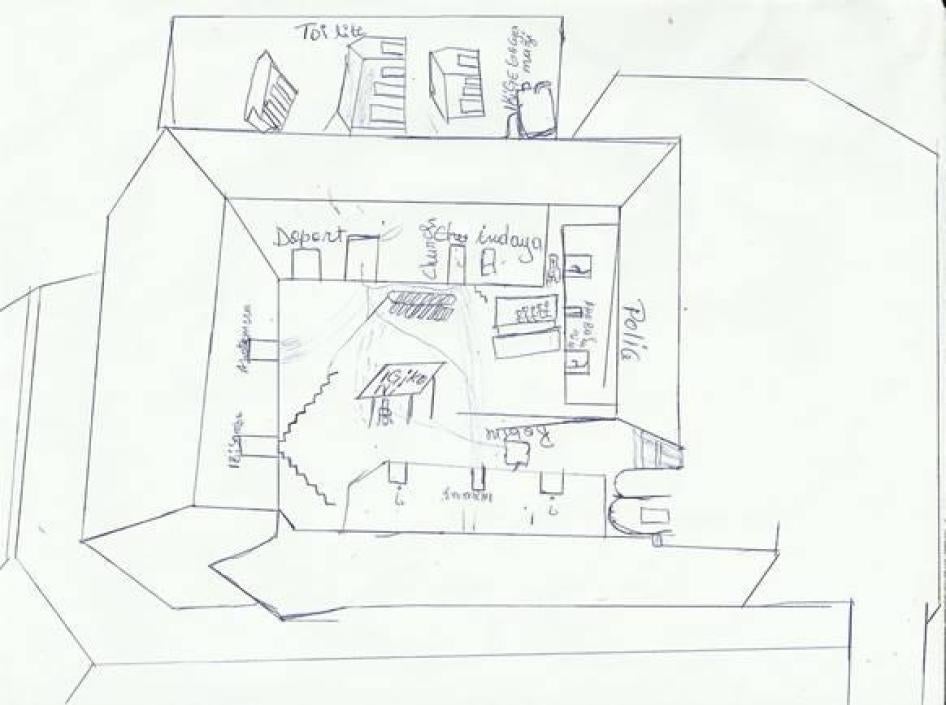

The center consists of a large warehouse built around a courtyard. The buildings are all single story, except for one section that has a second floor. A Catholic parish borders the center. Residential homes are located within a few meters of the perimeter walls.

Former detainees described the layout of the center to Human Rights Watch. One former detainee said, “Kwa Kabuga has four big rooms. They are like airplane hangars or classrooms, big and long.”[2] Another compared it to a large warehouse.[3]

The City of Kigali is responsible for the management of Gikondo and established the center through its council bylaws.[4] The police is responsible for the daily running and security of the center.

Rwandan government officials refer to the center as the Gikondo Transit Center.[5] Some officials have described it as a staging or processing area before those held there are moved to a rehabilitation center on Iwawa, an island in Lake Kivu, off the shore of western Rwanda. The center at Iwawa was created by presidential order[6] and is managed by the Ministry of Youth and ICT.

Gikondo has been used as a detention center since at least 2005. In its 2006 report, Human Rights Watch noted the lack of adequate food, water, and medical care, and abuse of children by adult detainees at Gikondo. Human Rights Watch called for the immediate closure of the center in 2006.[7]

The Rwandan government rejected the report’s findings. The minister of internal security, Sheikh Mussa Fazil Harerimana, was quoted in the media as saying, in 2006, "The facility was legally established by Kigali City Council through its Advisory Committee as a transit centre for the rehabilitation of homeless children and idlers before reuniting them with their families in the countryside.”[8]

Gikondo was temporarily closed in 2006 but reopened in 2007.[9] Over the nine years since Human Rights Watch’s first report on the center, conditions at Gikondo have worsened. More people have been unlawfully detained there and suffered humiliating abuses in a harsh environment.

In 2008 members of the Rwanda Senatorial Standing Committee on Social Welfare, Human Rights and Petitions requested the closure of the center based on a report of that committee stating that children’s rights were abused there. The then-Prime Minister Bernard Makuza defended the center, maintaining it was established by law, and the then-minister of gender and family promotion, Jeanne d’Arc Mujawamariya, was quoted in the media as telling the Senate, “Before, [in Gikondo] children used to be enclosed in a very dark hall which was [in] a terrible condition but after we intervened, they now move and play freely in the compound.”[10]

In August 2014, the office of the Mayor of Kigali and the National Commission for Children announced in a meeting thatchildren would not stay at Gikondo Transit Center and that if a child did arrive there, “the child must be immediately sent to another place that suits him.”[11] This welcome decision was an admission that children should not be held in this facility. Human Rights Watch does not have any indication that children have been detained at Gikondo since the second half of 2014. However, adults, including women with infants, continued to be detained at the center throughout 2014 and into 2015.

II. Police Arrests and Human Rights Abuses at Gikondo

Police round-ups of poor people on the streets of Kigali are often the first step towards unlawful detention and inhuman and degrading treatment at Gikondo. The arbitrary manner in which these people are arrested is consistent with the complete absence of due process that continues once they are detained at Gikondo.

Police Arrests and Transfers to Gikondo

All but one of the 57 former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were held in police custody before being transferred to Gikondo. They were arrested and taken to a variety of police stations or sector (local government) offices across Kigali, the most common being the police stations at Nyabugogo (known as “the Office”), Nyarugenge (known as “Criminologie”), Nyamirambo, Kicukiro, and the Muhima sector office.[12] Some former detainees told Human Rights Watch that police officers or local security forces–the Local Defense Force or Inkeragutabara[13]–beat them at police stations.

People were often arrested in large numbers, sometimes as many as 70 at a time, then transported to Gikondo in large trucks. A former detainee told Human Rights Watch, “I was arrested by the Local Defense… I was taken to the police station at Nyarugenge. Fifty or sixty people were arrested. The truck was full. We arrived at Nyarugenge police station around 8 p.m. The next day at 5 a.m., the Tata [truck] came to take us to Kwa Kabuga.”[14]

A former detainee described to Human Rights Watch the frequency with which people were taken to Gikondo from “the Office” in Nyabugogo: “They take people in waves. Sometimes it will be a few days with nobody taken [there], then they arrest many people. Even today, people were arrested at Nyabugogo. First you are taken to ‘the Office’ at the bus station. There it is like a jail. Then you are taken to Kwa Kabuga, usually at night.”[15]

A former detainee who spent a night at Nyamirambo police station in 2014 told Human Rights Watch:

I was going to the market at around 8.30 p.m. I saw men collecting and checking ID cards. It was the police with the Inkeragutabara. They were stopping women. I explained that I was going to the market, but they accused me of being a prostitute… I was put in a panda gali [pick-up truck] and taken to the jail at Nyamirambo… We spent the night there… The police announced, ‘We are going to take you to Gikondo because you are vagabonds.’ At Nyamirambo we slept on the ground in the cell. When we wanted to use the toilet, the police would hit us. There were men and women in the room. Some of the women had their children with them.[16]

A sex worker told Human Rights Watch that she was among a group of about 30 people who were arrested at midnight at a bar in 2014, taken to the Muhima sector office, then to Gikondo.[17] Another sex worker told Human Rights Watch:

I was at home when I was arrested. There was a knock on the door. It was the Inkeragutabara. They had gathered many people that night. They were saying, ‘We are arresting the prostitutes!’ They tied us to each other with our clothes. We spent the night at the sector office. All night long we were beaten. The Inkeragutabara made us lie down and hit us. While they were hitting us, they were saying, ‘You are whores, you spent the night moving around!’ The next day, we were maybe 100 women there and the Tata [truck] had to make three trips to take us to Kwa Kabuga.[18]

Conditions at Gikondo

Categories of Detainees

Former detainees described four main categories of people held at Gikondo: women, children, men accused of minor offenses, and men accused of serious crimes.[19] On arrival, detainees were assigned to a specific room, according to their “category.”

Detainees had different names to describe these rooms. They often referred to the women’s room as the room for prostitutes or sex workers, even though many of the women were arrested for other alleged offenses and activities, such as street hawking.

|

Infants in Detention Many women, especially street vendors, were arrested with their young children. Human Rights Watch interviewed ten women who were detained at Gikondo with their young children, some of whom were under one year old, others as old as four. One woman who had been detained at Gikondo four times told Human Rights Watch that each time, she had to keep her youngest child with her because there was nobody else to take care of her.[20] During her most recent detention in February 2014, she was held for two weeks with her one-year-old daughter. The conditions at Gikondo are particularly unsuitable for young children. Former detainees told Human Rights Watch that while young children were given extra food, the quantity was not sufficient. They were not provided with milk or baby food. One former female detainee told Human Rights Watch, “The kids are given porridge once a day but it was bad and mixed with water. Sometimes there was no porridge so they gave them water that was used to cook the beans.”[21] Another woman, who spent two weeks at Gikondo, told Human Rights Watch, “I had my son with me… He was under one year old. The conditions there are not good for a baby. There are mad people there. There are insects in the mattresses and everything is dirty.”[22] Despite the harsh conditions, some women told Human Rights Watch that they preferred to keep their young children with them because there was no one to look after them at home. Having a young child in Gikondo also meant they could receive extra food and benefit from the prospect of an early release. One former detainee told Human Rights Watch, “You are lucky if you are taken with your child because at least you have some small privileges.”[23] Some women were released when their young children got sick. A former detainee who spent one month at Gikondo with her 7-month-old son in 2013 told Human Rights Watch, “My son got sick in his mouth and it became difficult for him to eat. It was then they decided I had to go.”[24] |

Detainees spoke of a second room where street children, vagabonds and street hawkers were held together. A former detainee explained the difference between street children and vagabonds: “Street kids sleep under the bridge, but you can be a vagabond and still have a house. Some vagabonds are money changers.”[25] Street hawkers are also commonly referred to as “businessmen” as they sell items such as clothing and shoes. Many are adults with established homes. Between 2011 and 2014, Human Rights Watch documented the presence of adults–persons over 18 years old–in this room.

A third room, for men accused of minor offenses, is commonly called the room for “men who stole and who continue to deny it” or abatemera in Kinyarwanda.

The fourth room, commonly called the indege or the CID room,[26] is for men suspected of committing serious crimes, who are unlikely to be released back onto the streets and who, presumably, will eventually be charged and tried. Some former detainees also called it “the room for dangerous men,” “the room for criminals,” “the room for ninjas,” or “the room for men who do karate.” This is because these men are regarded as so dangerous that they will fight anyone.

In 2013 Human Rights Watch spoke to six men who had spent time in the indege room. Several had been transferred to Gikondo from Kwa Gacinya, a police station in the Gikondo area, where people accused of serious crimes are detained.[27] One former detainee told Human Rights Watch:

The other prisoners were scared of us and they left us alone because they knew we had come from Kwa Gacinya … There were so many fleas there [in the CID room] you could pick them up with your hands… Street kids and women would come and go at Kwa Kabuga, but the people in the CID room did not leave. To leave the CID room, the order needed to come from an afande [official]. If he did not let you out, then you did not leave.[28]

Another former detainee told Human Rights Watch:

After a month at Kwa Gacinya, I was taken to Kwa Kabuga. It is a bad place. I was put in the “room for dangerous men” for almost three months. People there had to sleep body to body. There was a thin mattress on the ground and it was covered in fleas… I was suffering from the torture in Kwa Gacinya. I was sick.[29]

The six men Human Rights Watch spoke with were brought before a court where they were charged with theft and transferred to recognized detention facilities. They had spent a total of approximately six weeks in unlawful detention at Gikondo and Kwa Gacinya.

Beatings

The “counselor” would beat us to make us sleep.

−Former detainee in Gikondo Transit Center, Kigali, June 11, 2014

If you get sick, the “counselor” can beat you until you are better.

−Former detainee in Gikondo Transit Center, Kigali, January 14, 2013

Forty-one former detainees told Human Rights Watch they were beaten in Gikondo and seven described seeing beatings of other detainees.

The majority of beatings reported to Human Rights Watch were carried out by other prisoners, called “counselors.” While the police are responsible for the overall management of Gikondo, inside the rooms, in practice, the detainees are responsible for their own security and organization. Each room is managed by a “counselor” chosen by the police; the “counselors” appoint deputies to help them manage other detainees. “Counselors” are detainees who have spent long periods at Gikondo, often several months. Police give them de facto authority to ill-treat other detainees.

A 21-year-old former male detainee described the “counselors” as “prisoners who have been there a long time. They can seriously beat us. They are recognized by the administration. They carry a wooden stick.”[30] The same system operates in the women’s room, where female “counselors” also beat female detainees.[31]

Some detainees also spoke of beatings by the police. A female detainee told Human Rights Watch, “The police can beat you outside… Even when you get out of the truck when you arrive, if you turn towards the men’s room or turn around, they hit you. The police can beat you anywhere… But inside [the room] it is the ‘counselor’ who can beat you.”[32] Another former detainee told Human Rights Watch, “Once we had a dispute among ourselves and the police came in to beat us. Sometimes the two groups−the vendors and the prostitutes−have fights. So the police enter and beat everyone except the babies. The police used to say, ‘Have you just come here to be beaten?’”[33]

Paying “Candle Money”

The first beating usually took place just after the police registered new detainees and directed them to their assigned room. Whether or not detainees were subject to this initial physical abuse could depend on whether they had money to hand over.

Beatings by the “counselors” or their deputies are partly designed to extort money “to buy candles,” meaning that the detainee must pay the “counselor” to avoid being beaten. One hundred Rwandan francs (roughly US$0.15) could be enough to avoid a beating. However, as many of the detainees in Gikondo are destitute, they cannot afford even this modest sum. Moreover, several former detainees told Human Rights Watch that what little money they possessed had already been taken by other detainees in the police cells where they were held when they were first arrested, before being transferred to Gikondo.

A former female detainee told Human Rights Watch, “There was a woman in charge of the room. She is a prostitute. She was bad. She beat us. She asked for money when we entered. She said she needed money to buy candles. When we said we did not have any, she would beat us with a wooden stick.”[34] A former male detainee who had been detained at Gikondo several times told Human Rights Watch, “At Kwa Kabuga it is always the same. You are asked for money for the candle by a ‘counselor.’ If you do not have it, you are beaten.”[35]

For detainees accused of being street children, the process of paying “candle money” could be particularly degrading. Several minors told Human Rights Watch that they had to hold a bucket of excrement while they were beaten if they did not have the money.

A 17-year-old former detainee told Human Rights Watch:

I was questioned by a prisoner, but he was like a boss. He was an adult … He said, ‘Give me the candle money.’ But I had no money. So he said ‘Hug the bucket of [excrement].’ So I had to wrap my arms around the bucket that had the [excrement]. Then he hit me on my back.[36]

Daily Beatings

The beating for “candle money” is only the first of many beatings at Gikondo. Numerous detainees told Human Rights Watch that beatings by the “counselors” or their deputies were commonplace.

One former detainee told Human Rights Watch, “Each morning I was hit by the ‘counselor’. He would hit us when we were getting in line to use the toilet. This happened to many people. I was not singled out for these beatings.”[37]

A female former detainee told Human Rights Watch:

The ‘counselor’ can beat you when you do something wrong. She beats you with a wooden stick. She can make you empty the bucket [of excrement]. If you refuse, you are beaten. You are made to lie down on your stomach and you are beaten. I was beaten because I refused to do this.[38]

Former detainees told Human Rights Watch that they were beaten for ordinary requests, such as asking to use the toilet or talking, when it was apparently not allowed.[39] A former detainee, who appeared traumatized, told Human Rights Watch, “The ‘counselor’ beat us like cows. He always has his stick and he can beat you if you move. If you get into a dispute for a place in the room, you are beaten.”[40]

Beatings of Women with Young Children

Female detainees with young children or babies were particularly vulnerable as they were frequently beaten when a small child or baby defecated on the floor. Defecation on the floor by a detainee’s child is considered a serious offense at Gikondo. Human Rights Watch spoke with several former female detainees who were either beaten for this or witnessed other women beaten. One former female detainee told Human Rights Watch:

If your child goes to the toilet on the ground, then it is serious. They will beat you and shout at you: ‘You are making this place dirty!’ They want children to [defecate] in their own clothes. Last year, I gave my clothes to my baby because she had [defecated] in hers. I could not wash them.[41]

There is often no water in the room, and detainees are not allowed to go out of the room except at fixed times, to use the toilet (see below).

Another former female detainee, who had been detained at the center four times, told Human Rights Watch:

My child had a bad stomach and she could not leave the room to use the toilet. If a child [defecates] in the room, they hit the mother. The ‘counselor’ does it. My daughter needed to use the toilet and I tried to open the door, but the counselor refused. Since my child was in pain, I decided I would rather be beaten so she could use the toilet. This happened to me twice. You just hand your child to a friend and you lie down. Then the counselor hits you.[42]

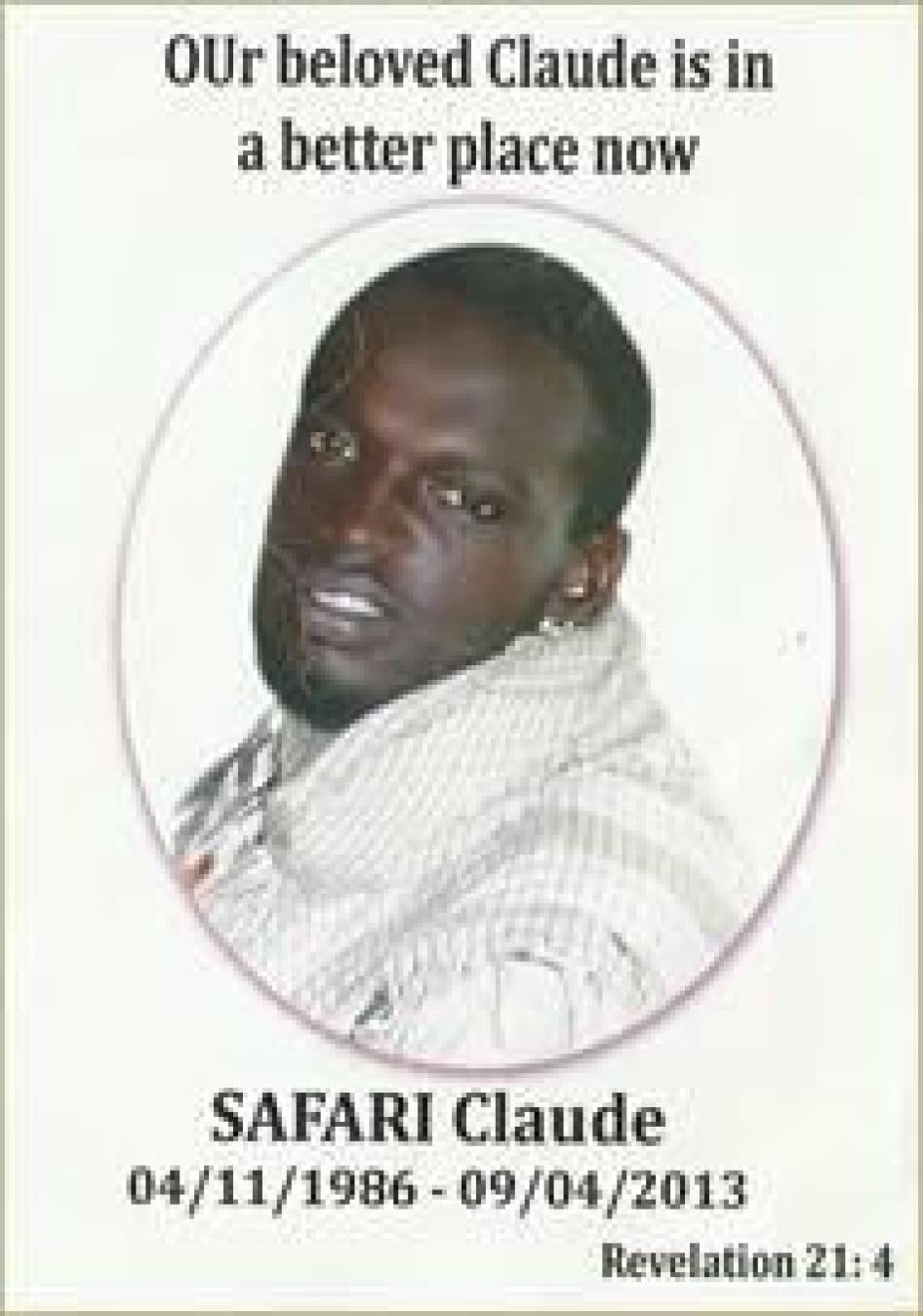

The Death of Jean-Claude Safari

Jean-Claude Safari, a 26-year-old man arrested on suspicion of theft, was detained in Gikondo from February 21 to March 29, 2013. Individuals close to him told Human Rights Watch they initially thought he was being “re-educated” at the center. One of them said, “I had confidence in the state agents there.”[43]

When Claude arrived [at Gikondo] he said the Inkeragutabara had beaten him [in the police station, before he was transferred to Gikondo] and he was really hurting on his side. We shared a sheet on the ground. When he moved in his sleep, he would wake up in pain. He told the officials at Kwa Kabuga that he was in pain, but they said, ‘No, you have only just arrived. You can’t be sick yet.’ Claude had diarrhea and it was difficult for him to eat. He would give his rations to other people… Claude, like all of us, was beaten by the prisoner in charge of security… When the beatings started, he tried to hide, but the ‘counselor’ would often point him out and say, ‘You are pretending to be sick, but you are not sick.’ Then they beat him… His health worsened, but nobody noticed. That is because there were others there in even worse shape than him. Just before he was released, Claude said, ‘I am suffering too much. I hope I am freed. Here I am in danger.’ He was very weak when he left. He had been beaten at Kwa Kabuga so much that his knee was swollen and he was limping. He was also so thin.[44]

When Safari was released on March 29, 2013, people close to him confirmed that he had become noticeably weak and thin. Soon after his release, he told a friend, “People are dying in there. I am so happy to leave that place. I was beaten so much there. I was beaten by a head prisoner, chosen by the police.”[45] He also told friends and relatives that he was still suffering from the beatings by the Inkeragutabara before he was transferred to Gikondo.

Soon after his release, Safari stopped eating, complaining of severe stomach ache. A few days later he started complaining of headaches and a fever. He was taken to a clinic on April 3, 2013, transferred to the hospital on April 7, and died on April 9.

A police autopsy on April 14, 2013, at the Kacyiru Police Hospital stated the cause of death as “violent” and cited a “probable episode of assault” as a consideration.[46]

Five people, including two policemen, were charged with grievous bodily harm in connection with Safari’s death. They were accused of beating Safari during a night patrol, at the time of his arrest, before he was taken to Gikondo. On October 25, 2013, the court of first instance of Nyarugenge, in Kigali, ruled that there was insufficient evidence against the defendants and found them all not guilty. The prosecution appealed, but the high court in Kigali upheld the judgment and confirmed their acquittal.[47]

Space, Food, Health, and Hygiene

Gikondo is a bad, bad place.

−Former detainee in Gikondo Transit Center, Kigali, March 5, 2014

The Rwandan government told Human Rights Watch that “the living conditions in the Transit Center are conducive and clean, and [detainees] are fed twice a day, given sanitary and recreation facilities. All these services are conducted by full-time psychosocial counselors and health workers (primary and secondary healthcare and VCT [voluntary counseling and testing for HIV/AIDS]).”[48]

This picture stands in sharp contrast with the conditions former detainees described to Human Rights Watch.

Former detainees described harsh living conditions at Gikondo. Several hundred detainees could be made to share a large room and sometimes did not have enough space to move or lie down. One former detainee told Human Rights Watch that the women’s room was sometimes so crowded that they had to sleep on their sides in a line.[49]

The center provides mattresses but detainees complained of a shortage. A 15-year-old former detainee told Human Rights Watch that he had to share a mattress with two other boys for two months in early 2014.[50] Many former detainees reported that fleas and lice infested their mattresses, sheets, and clothes.

Food at Gikondo is inadequate. The Rwandan government said food was provided twice a day, but former detainees told Human Rights Watch that the standard ration was a cup of boiled maize, sometimes mixed with beans, once a day. Young children who are with their mothers are often given a second meal, usually porridge. Former detainees spoke of a shortage of food and firewood for cooking. One former detainee told Human Rights Watch, “Often there was no wood to cook, so [the counselors] would say, ‘Ok, spend the night without eating.’ Once we went three days without eating. Even the children do not eat when there is no wood.”[51]

Water is given to detainees on a sporadic basis. Many former detainees told Human Rights Watch it was insufficient and dirty. One former detainee said, “There was a jerry can for water in the room, but it was often empty.”[52] Another told Human Rights Watch, “We would get water once in a while… it was dirty and had bugs in it.”[53]

Most former detainees told Human Rights Watch that they would go several days, sometimes over a week, without washing. Some said they never washed during a period of several weeks. No provisions are made for female detainees’ menstrual or other hygiene needs.

Toilets are located outside, behind the women’s room. Detainees are taken out in groups, standing in line to use the toilets. They are allowed to use the toilet once or twice a day, depending on how many people are detained. The toilets are filthy. One former detainee told Human Rights Watch, “The toilet was bad. You were in a line and there was no door. Even if you were not finished, you were forced to leave.”[54]

Women reported using the toilet twice a day at fixed times−the same toilets used by the men and children. One female former detainee described the toilets as “dirty” and “horrible;” she said they used them at around 4 a.m. and 4 p.m.[55] Another former female detainee told Human Rights Watch, “The toilets do not have doors. You have to cover yourself to use the toilet. People go out in groups of ten and we could be beaten going there.”[56]

Former detainees held at Gikondo in September 2014 told Human Rights Watch that the toilets had filled up with excrement and described how they had to use open trenches next to the toilets to relieve themselves. This trench was still being used in February 2015. In September 2015 satellite imagery appeared to show that new toilets were under construction. Human Rights Watch has not been able to access the center to confirm this.

For some of the men and children−when children were still being detained at the center−there were also plastic jerry cans in the rooms, which detainees used as toilets. One adult former detainee explained to Human Rights Watch, “The toilet in the room is a jerry can cut in half, one side for [urine] and one side for [excrement]. The room is closed at night and the door is locked. If the jerry can is full, you have to arrange another way and quietly find a corner.”[57]

Women did not report using a jerry can if they needed to use the toilet outside set hours. One former female detainee told Human Rights Watch, “If you need to use the toilet in the room you go on the ground, but you need to clean it up yourself.”[58]

Former detainees told Human Rights Watch of sporadic visits by health care workers, especially to test for HIV. However, most said there was no recourse or available treatment if they fell ill.[59] One said that he requested medical attention, but was told he had not spent enough time at Gikondo to merit being sick or receiving treatment.[60]

Human Rights Watch spoke with dozens of detainees who were tested for HIV/AIDS upon arrival, suggesting that the practice is common.[61] However, according to these detainees, HIV/AIDS testing was not voluntary and detainees did not receive counseling. Some former detainees told Human Rights Watch that they did not have access to important medication and were released only after they started to show signs of illness. A 27-year-old HIV positive former female detainee, who had been held at Gikondo at least six times, told Human Rights Watch, “They tested me [because] the police had told the nurse to verify if I was really HIV positive… I tested positive… but it was only when I started showing signs of illness that I was released… I normally get my medicine once a month and I take it each day. I started ARVs [anti-retroviral medicines] in 2006, but when I was in Kwa Kabuga I did not get them.”[62]

Visits to Gikondo

Gikondo is often the first place friends and family look for people who go missing in Kigali because it is so well known. Police guards at Gikondo often note the names of detainees and can confirm to friends and family whether the person they are looking for is detained there. However, friends and family are not allowed to visit detainees.

Detainees at Gikondo are not allowed to contact relatives or lawyers to inform them that they are held at the center. Former detainees told Human Rights Watch that they usually informed friends and family indirectly that they were detained there, for example by passing messages through other detainees when they were released.

When Human Rights Watch asked a former detainee about access to legal assistance, she laughed and said, “Once inside, it is not possible to get a lawyer… People cannot visit there because it is not an official prison.”[63]

Some Rwandan nongovernmental organizations have had irregular access to the center. On March 11, 2013, representatives of Association Centre Marembo, an organization that promotes youth initiatives, visited Gikondo and posted photos on Facebook of female reproductive health trainings it facilitated at the center.[64]

A local organization for the protection of street children, linked to the Catholic Diocese, Abadacogora/Intwari, has visited the center over recent years, including in 2014 to secure the release of detained children.

Former detainees at Gikondo told Human Rights Watch of rare visits by foreigners, whom they described as “journalists,” even though some of the visitors may not have been journalists. They said the police tightly controlled these visits and prepared them in advance in order to present an artificially positive image of the center.

Some former detainees told Human Rights Watch that the police told them how to behave during these visits. One former detainee said, “Some radio journalists came to talk to us at the site… The police said to us, ‘Don’t make a mistake. Be careful.’”[65]

Another former detainee told Human Rights Watch, “Some journalists had come and we were told to lie and say that we lived well there and that we were given milk. The police said that if we said that, then afterwards we would be released.”[66] Another detainee told Human Rights Watch how the police hid groups of detainees behind the toilets when “international journalists” arrived.[67]

A former detainee who was held at the center in 2012 told Human Rights Watch, “There were foreigners who came to visit, but they were not allowed to see many people. We were forced to say, ‘Yes, we eat well and they give us good clothes.’ When the white people came, they took people out to show them a small number. They said to us, ‘Don’t make a mistake and say you are badly treated here. Say you are well treated.’”[68]

Human Rights Watch is aware of two visits to Gikondo by foreign embassy staff in Rwanda: one in 2008, and another in 2012.

A foreign visitor to Gikondo in 2012 told Human Rights Watch:

At Gikondo it seems to be largely indiscriminate detention. We are told they are there for up to two to three weeks. They cleaned it up before we arrived and there were no women there. It was a mix of kids and adults. The authorities refused to answer some questions… There were not many people there. We were unclear about how people come and go. In practice the police bring them, but it was not clear. [The authorities] did not really address our questions about how one gets in and out.[69]

Human Rights Watch has sought to visit Gikondo on several occasions since 2011 but Rwandan authorities did not grant the necessary authorization.

Release from Gikondo

If you want to leave, it is easy: you pay.

−Former detainee in Gikondo Transit Center, Kigali, September 2012

Detainees are released from Gikondo with very little formal procedure, reflecting the arbitrary manner in which they were initially arrested. Since those held in Gikondo are not detained in accordance with any judicial proceeding, there is no official period after which they are automatically released by law, nor appear before a judicial officer for release. As the minister of justice explained, “there is no prescribed length of stay at the Gikondo Transit Center.”[70]

While some street children told Human Rights Watch the police at the detention center used to register them before they were released, most said they were just told to leave. However, many adults, especially sex workers and street vendors, told Human Rights Watch they had to pay to leave; for example, 11 former detainees released between July 2013 and June 2014 said they had paid to be released. Several others said that they could have left if they had been able to pay, but were not able to raise the money.

Only two former detainees, both street children, told Human Rights Watch that they saw groups of detainees preparing to depart for the rehabilitation center at Iwawa Island. Other former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch were simply released back onto the streets after the police read their names off a list and told them to leave.[71]

Some former detainees told Human Rights Watch that local authorities visited Gikondo on the day of their release. For example, one former female detainee told Human Rights Watch:

In 2012 a local leader came and held a meeting. He was the executive secretary [local government official] of the sector [of Gikondo]. He was with executive secretaries of other sectors. They released people who had identification documents. The executive secretary said, ‘Go to your homes, take up the hoe and cultivate and do not return to Kigali.’ He meant that we were to return to our hill [area] of origin.[72]

Decisions on releases are often arbitrary and there appear to be no clear procedures or criteria. As one female vegetable seller and former detainee told Human Rights Watch, “Sometimes the police just decide that someone has spent a lot of time there and she can leave.”[73]

As mentioned above, detainees who are visibly in poor health, especially those with HIV, or those with sick children, are released more quickly. One former female detainee with tuberculosis, who was held with her child, told Human Rights Watch that after two months of detention in late 2013, she became very sick and asked to go to the hospital. Her request was granted and she was released.[74]

Payment for Release

The easiest way for adults to leave the center is to pay the police. Several former detainees told Human Rights Watch that opportunities for payment started from the moment they were arrested and continued throughout their stay in Gikondo. One former detainee described the system:

At Kwa Kabuga women pay 10,000 Rwandan francs (approximately USD$14) and men 20,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $28). [But] in the panda gali [pick-up truck] you can pay before arriving at the police station. It is 5,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $7) for women and 10,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $14) for men. If it’s the Inkeragutabara, you pay only 1,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $1.5). The police want more. You can only pay the Inkeragutabara before you are put in the panda gali.[75]

Many former detainees told Human Rights Watch that corruption by police and Inkeragutabara could determine whether they ended up in Gikondo. One former detainee told Human Rights Watch in January 2015, “Last week I was arrested, but my sister paid 5,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $7) to free me at ‘the Office’.”[76] On March 8, 2014, a Human Rights Watch researcher witnessed members of the Inkeragutabara harassing a group of men and women in Nyarugenge. One of the women later told the researcher:

The Inkeragutabara told us, ‘You need to pay for the fuel the police use to chase you.’ The men who sell shoes collected money and paid 2,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $3) directly. [But we women had no money] so we pleaded and pleaded and finally they let us go. We were lucky. But last night three of us women were caught again and we each had to pay 1,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $1.5). This happens often. If you pay they will not take you, but if you do not have the money, they can take your goods and you go to jail at Nyamirambo. From there they take you to Kwa Kabuga.[77]

Once at Gikondo, detainees or their relatives can pay the police at the gate. The father of one former detainee paid 10,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $14) to the police at the gate in exchange for her release.[78]

Another former detainee told Human Rights Watch:

At the door there are police and you can approach them. [The policeman] fixes a price and he will say something like, ‘I need to buy phone credit’. That is the code. Then you negotiate the price. They usually start at 30,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $43) and you start at 10,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $14) and you settle on 20,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $28).[79]

Many payments are also made through detainees’ personal networks to a policeman outside the center. A former detainee described the process:

It is a chain; someone outside has to know a police officer … To get out of Kwa Kabuga I paid 15,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $21). After two weeks, I arranged it with the police. I had someone outside. I sent a note to her and said I was at Kwa Kabuga and I asked her to come. I sent that note via a policeman and he arranged the payment. Then she paid for me.[80]

The amounts detainees or their families pay can vary. A former detainee told Human Rights Watch:

My brother negotiated for me. He knew a woman who could help. They had to pay 50,000 Rwandan francs (approximately $71). My family raised the money and we gave it to the police officer via this woman. The next day the police knew that I had arranged to pay. I left after 40 days there.[81]

Rwandan authorities have undertaken to investigate allegations of corruption at Gikondo. In his letter to Human Rights Watch in November 2014, the minister of justice wrote: “In relation to the issue of possible cases of corruption by members of the Rwanda National Police, the Rwanda National Police administration has been informed and the allegations are being seriously investigated […] the Government is resolved to prosecute and punish cases of corruption wherever they are found.” He encouraged Human Rights Watch and others to produce any other information which could help investigations.[82] In a meeting with Human Rights Watch in December 2014, the ombudsman said her office would immediately start an investigation into allegations of corruption in Gikondo and encouraged victims of corruption, especially poor people, to report cases to her.[83]

Returning to Gikondo

I can’t even count how many times I have been to Kwa Kabuga.

−Former detainee in Gikondo Transit Center, Kigali, July 2014

Every day I risk going back to Kwa Kabuga, but I continue working. They say they send us there to correct us or to get us to abandon our trade, but we don’t have money to start a restaurant or a bar. The police just say, ‘Abandon your work’, but what can we do?

−Street vendor and former detainee in Gikondo Transit Center, Kigali, March 2014

Thirty-three of the 57 former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch had been detained at Gikondo more than once. Many, especially sex workers, had been held in Gikondo more than five times. Several said they had lost count of how many times they had been there. Human Rights Watch did not find indications that detention in Gikondo had any effect in deterring what is deemed anti-social behavior. On the contrary, all the former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch had resumed the work or activity that had led to their arrest, for lack of viable alternatives.

In some cases, their arrest aggravated the situation. For example, women who used to hawk goods on the streets reported that the police seized their goods when they arrested them and did not return them when they were released. Some women said they had no alternative but to turn to sex work after their release from Gikondo, because all the stock which had enabled them to earn a meagre living before their arrest had been confiscated.[84]

One former detainee, who had been sent to Gikondo in 2012 for six weeks for selling eggs on the street, told Human Rights Watch five months after his release, “Of course I now am selling eggs again. It is my only business.”[85] A female street vendor and former detainee told Human Rights Watch, “I continue to do the same work. I am not afraid. I can’t stop working because it is a question of life and death. I do the same work in the same place. I would rather work than die of hunger.”[86]

Former detainees told Human Rights Watch that if the police established that certain detainees had been in Gikondo before, they risked being detained for longer periods. One former detainee told Human Rights Watch, “When you are released, the police say, ‘If you come back, you will have problems.’”[87] Many detainees therefore lied or changed their names as they entered the center for the second, third, or fourth time.[88]

The practice of repeated detentions in Gikondo has been taking place for many years. In a 2008 confidential cable from the United States Embassy in Kigali, released on WikiLeaks, US embassy staff wrote, “[Center] officials freely admitted many of the center inhabitants had been there before, particularly among the prostitutes−some on their fifth or sixth stay.”[89]

III. The Rwandan Government’s Position on Gikondo

They say Kwa Kabuga is a re-education center, but it is a prison. So I ask: why not call this place a prison?

−Former detainee in Gikondo Transit Center, Kigali, February 2014

The Rwandan government’s attitude towards Gikondo has been contradictory, with discrepancies between the official discourse and the reality. The government recognizes Gikondo only as a transit center, consistently denying the reality that it functions as detention center.

Human Rights Watch sought to share its research findings on Gikondo with several Rwandan government officials in 2012, 2013, and 2014.

On August 5, 2014, Human Rights Watch sent letters requesting meetings to the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion, the Ministry of Youth and ICT, the Ministry of Local Government, the Ministry of Internal Security, and the mayor and the vice-mayor of Kigali. None of these officials agreed to meet Human Rights Watch about Gikondo. Some did not reply; others referred Human Rights Watch to the Ministry of Justice.

On August 14, 2014, Human Rights Watch wrote to Johnston Busingye, minister of justice, outlining its human rights concerns at Gikondo, asking for further information on the center and requesting a meeting. The minister’s letter, reproduced in Annex I of this report, represents the Rwandan government’s most substantial response to Human Rights Watch’s concerns about Gikondo to date. In his letter, the minister stated: “The Gikondo Transit Centre is not nor has it ever been designated as a detention facility. It is a center for social emergency assistance… It is part of the general Rwandan philosophy of rehabilitation rather than unnecessary incarceration… The living conditions in the Transit Center are conducive, they [detainees] live in a clean environment, and they are fed twice a day, given sanitary and recreational facilities.”[90]

On August 21, 2014, the minister of justice gave several interviews to Rwandan radio stations in which he asserted that the center known as Kwa Kabuga did not exist but that there were re-education centers for vagabonds, street children, and people who take drugs.[91]

Previously, in 2012, Human Rights Watch had raised the illegal nature of detentions at Gikondo with the then-minister of justice, Tharcisse Karugarama. He responded, “There is nothing on Kabuga’s place. You are telling me rumors and hogwash.”[92]

On December 24, 2014, Human Rights Watch met with the ombudsman, Aloysie Cyanzayire. She told Human Rights Watch, “[Gikondo] is not a detention center. It is a transit and rehabilitation center. The law on Iwawa gives instruction for it to be established.” As stated above, however, she appeared to take allegations of corruption seriously and said, “We will certainly start an investigation into this. We will start immediately.”[93]

Concerns about Gikondo have also been raised in international fora. One of the recommendations in Rwanda’s Universal Periodic Review before the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2011 was for Rwanda to “urgently investigate cases of arbitrary arrest and detention, including those which may constitute enforced disappearances.”[94] In its response, the Rwandan government stated: “Rwanda used to have cases of beggars and street children who happened to be taken from streets to the transit centre of Gikondo (in Kigali City) where they were sensitized and encouraged to join cooperatives or existing child rehabilitation centres. But it would be erroneous to assimilate those cases to arbitrary arrests and detentions.”[95]

In the 2013 concluding observations on the third and fourth periodic reports of Rwanda for the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child,[96] the Committee on the Rights of the Child noted, “Children in vulnerable situations, such as children living in street situations and victims of child prostitution continue to be perceived as offenders and detained in an unofficial detention center in Gikondo under poor living conditions and without any charges.”[97] The Committee asked the government of Rwanda to “permanently close all unofficial places of detention, including the detention centre in Gikondo and stop the arbitrary detention of children in need of protection… and conduct thorough investigations of acts of arbitrary detention, ill treatment, and other abuses occurring in the centres.”[98]

In response to the Committee’s questions, the Rwandan government stated, “Gikondo is a transit centre [to] help police to deal with children in/on street waiting for their parents [to] come eventually recover them before directed[ing] them to reintegration centers for their education.”[99]

Response of the Police

The Rwandan police, through press statements, has periodically referred to “screenings” (which the police appear to define as informal training), “re-education” or “encouragement” of detainees at Gikondo.

On October 4, 2013, the Rwanda National Police published a press release stating that 62 “wrongdoers” apprehended in Kigali were “taken to Gikondo Transit Center for screening, where they will be given civic education including how and where to operate businesses to avoid engaging in illegal acts and to turn them into good citizens.”[100]

In a press release on August 7, 2013, the Rwanda National Police stated that the previous day, it had arrested 117 suspected criminals. The police spokesman for the central region, Senior Supt. Urbain Mwiseneza, was quoted as saying that those apprehended were taken to Gikondo Transit Center for screening. “At the centre, they are given civic education and urged (vendors) to form cooperative societies, which helps their businesses to grow instead of remaining on streets, which is illegal and threatens security. For those involved in other criminal acts, those found to be habitual are taken to Iwawa Rehabilitation and Vocational Development Centre.”[101]

In another press release on February 12, 2014, the police referred to Gikondo as a “re-education center” after nine people were detained there for not having identification documents.[102]

Human Rights Watch met the then-police spokesman, Damas Gatare, to discuss concerns in Gikondo, in December 2013. Gatare said that Gikondo was “a transit center where people who have broken the law… or people who have been arrested pass through for screening before they are taken into detention.”[103]

On October 23, 2014 Human Rights Watch requested a meeting with Emmanuel Gasana, the inspector general of the Rwanda National Police, to share its findings in greater detail and seek information on the role of the police at Gikondo. In a written response, Gasana referred Human Rights Watch to the Ministry of Justice.[104]

IV. National and International Legal Standards

Rwandan Laws

There is no legal basis for the establishment and operation of Gikondo as a detention center. In his letter to Human Rights Watch in November 2014, the minister of justice conceded that “unfortunately, because of the manner in which the center was established as an emergency and temporary rehabilitation center, there is currently no legal framework for its administration. This loop hole has however been realized and a draft law and policy are in the final stages of development by the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion.”[105] At time of writing, Human Rights Watch is still seeking information on the progress of this draft law, but believes that the government should immediately close the center, rather than make efforts to maintain it, in light of the serious violations of human rights law that current detention practices at Gikondo raise.

More broadly, the existence of Gikondo reflects a government perception of certain groups of people as offenders or sources of nuisance, rather than victims or vulnerable members of society. This perception can be traced back to laws against anti-social behavior in the Rwandan Penal Code. The origins of these laws date back to a colonial decree from 1896 on rounding up vagrants.[106]

Many detainees in Gikondo are classed as “vagrants” or “prostitutes”. Article 687 of the Rwandan Penal Code defines vagrancy as “behaviour of a person who has no fixed abode and has no regular occupation or profession, in the way that it impairs public order.”[107] Persons convicted of vagrancy are liable to between two and six months in prison and a fine.

Sex work is criminalized in Rwanda and the Rwandan Penal Code provides for various punishments and sanctions, ranging from forced medical treatment to “surveillance measures”. Offenders are liable to prison terms ranging from three months to two years.[108]

The Rwandan Constitution provides that all Rwandans are entitled to equal protection before the law. Article 15 states that “every person has the right to physical and mental integrity [and] no one shall be subjected to torture, physical abuse or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.” Article 18 states that liberty is guaranteed by the state and that “no one shall be subjected… to detention or punishment unless provided for by laws into force at the time the offence was committed.”[109]

The Rwandan Penal Code prohibits “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, inhuman, cruel or degrading, are intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as… punishing him/her of an act he/she… committed or is suspected of having committed.”[110]

Rwandan law prohibits “detaining a person in a place other than a relevant custody facility” and “holding a person in detention for a period that exceeds the period specified in the arrest statement and provisional detention warrants.”[111] This offense is punishable with imprisonment of two to five years.[112] State agents found guilty of keeping a person in detention unlawfully are liable to imprisonment equivalent to the term incurred by the unlawfully detained person and a fine.[113] Persons convicted of unlawfully detaining someone for over a month can receive a prison sentence of up to seven years.[114]

The Rwandan Penal Code explicitly prohibits imposing severe suffering or severe or degrading punishments on children.[115]

Under Rwandan law, a judicial police officer may detain a suspect for up to five days without a court order if they have grounds to believe that a person is guilty of a crime punishable by at least two years’ imprisonment and would otherwise evade justice. The suspect should be released after five days unless a prosecutor orders a further five days’ detention if they are preparing a case file.[116] The suspect should then be released or charged with a criminal offense and brought before a judge to confirm provisional detention.[117] However, those detained at Gikondo do not appear to benefit from even these due process guarantees, as Rwandan authorities refuse to acknowledge that people deprived of liberty in Gikondo are in detention. Therefore there currently appears to be no judicial oversight of the detention of persons in Gikondo at all.

Rwanda amended article 40 of the Code of Criminal Procedure on custody facilities with a ministerial order on May 28, 2014, laying out the basic requirements to safeguard a detainee’s life and security, including adequate space, clean facilities, proper ventilation, toilets and bathrooms, and a room for consultation with a lawyer or a visitor.[118]

Transit centers in Rwanda are mentioned in a 2010 presidential order that establishes a rehabilitation center at Iwawa Island. Article 12 of this order states, “When the National Police arrests prostitutes, vagrants or beggars, it shall take them to the Transit Center in order to select those who are eligible to be taken to the Center [Iwawa] in conformity with the law.” Article 13 states that people should not be held at the transit center for longer than seven days. According to Article 6, people between the ages of 18 and 35 are admitted to Iwawa. [119] The center at Iwawa is managed by the Ministry of Youth and ICT. Human Rights Watch has not conducted extensive research on the rehabilitation center at Iwawa.

International and Regional Conventions and Standards

Practices at Gikondo violate several international and regional conventions which Rwanda has ratified and which prohibit arbitrary arrest and detention as well as cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

These include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),[120] the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT),[121] the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC),[122] the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Banjul Charter),[123] the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child,[124] and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol).[125]

Arbitrary Detention

Human Rights Watch considers that Rwanda’s “transit” centers, and in particular Gikondo, routinely hold people in violation of international and Rwandan law. Both the ICCPR and the Banjul Charter prohibit arbitrary arrest or detention and require that all deprivations of liberty have a clear basis in law and that all those detained are accorded full due process rights, including access to a lawyer and being brought before a judicial authority. According to the UN Human Rights Committee, detention is considered arbitrary if it is not in accordance with the law or if it presents “elements of inappropriateness, injustice, lack of predictability and due process of law.”[126] International law grants a detainee the right to challenge the lawfulness of his or her detention by petitioning an appropriate judicial authority to review whether the grounds for detention are lawful, reasonable, and necessary.

The UN Human Rights Committee has confirmed that Article 9(1) “is applicable to all deprivations of liberty, whether in criminal cases or in other cases such as, for example, mental illness, vagrancy, drug addiction, educational purposes, immigration control, etc.”[127]

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has also addressed governments on policies and practices that permit the detention of vulnerable groups, such as drug users and people suffering from AIDS. The Group expressed its concern in relation to such practices because “it is vulnerable persons that are involved, people who are often stigmatized by social stereotypes; but it is concerned above all because often such administrative detention is not subject to judicial supervision... With regard to persons deprived of their liberty on health grounds, the Working Group considers that in any event all persons affected by such measures must have judicial means of challenging their detention.”[128]

The procedures and practices for detention of persons at Gikondo do not meet any of the necessary safeguards required under international law to render a detention lawful, and the absence of proper grounds provided by law and due process rights for detainees renders detentions in Gikondo arbitrary.

Ill-Treatment and Inhuman Conditions in Custody

Treatment of detainees at Gikondo also violates international legal standards on the treatment of detainees, in particular the requirements that detainees be treated with humanity and the prohibition on all forms of ill-treatment. Officials in Gikondo inflict serious abuse, or allow serious abuse to be inflicted, on detainees, rising to at least the level of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. All ill-treatment of detainees violates Rwanda’s obligations under the ICCPR and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which set out the absolute prohibition on ill-treatment. Rwanda has a legal obligation to investigate credible allegations of cruel and inhuman treatment or punishment.

According to the ICCPR, “all persons deprived of their liberty shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person” and “[n]o one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”[129] The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, the authoritative guidelines on treatment of prisoners in accordance with international standards, states that “[c]orporal punishment... and all cruel, inhuman or degrading punishments shall be completely prohibited as punishments for disciplinary offences.” They also set out detainees’ basic rights in terms of accommodation, hygiene, bedding, food, medical services, and contact with the outside world.[130] Conditions and treatment in Gikondo fail to meet these minimum standards.

Detention of Women and Children

The treatment of women in Gikondo does not meet the standards contained in the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders, also known as “the Bangkok Rules,” which supplement the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. For example, the Bangkok Rules state: “Adequate and timely food, a healthy environment and regular exercise opportunities shall be provided… for pregnant women, babies, children and breastfeeding mothers”, and “The environment provided for such children’s upbringing shall be as close as possible to that of a child outside prison.”[131]

The treatment of infants in Gikondo also violates the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. The CRC obligates governments to protect children from “all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s) or any other person who has the care of the child.” It also states that any arrest, detention, or imprisonment of a child must conform with the law and can be done only as a “measure of last resort.” The detention of children in the same facilities as adults is prohibited by both treaties. Article 30 of the African Charter also requires state parties to provide special treatment to mothers of infants and young children, to establish special alternative institutions for holding such mothers, and to ensure that a mother shall not be imprisoned with her child.[132]

V. Conclusion

In 2006 Human Rights Watch documented harsh conditions, abuse of children, and prolonged unlawful detention at Gikondo. Despite increased public awareness of these concerns and pressure from inside and outside Rwanda to regularize the situation in Gikondo, nine years on, Gikondo is still used as an unlawful detention center. Hundreds if not thousands of detainees have been held there without charge or trial and subjected to ill-treatment and deplorable conditions, with little or no possibility of seeking redress. Although the practice of detaining children in Gikondo appears to have stopped since August 2014, Gikondo has continued to operate as a place of detention for adults, in violation of Rwandan law and regional and international conventions and norms.

The Rwandan government calls Gikondo a transit center. While some detainees have been transferred from Gikondo to the Iwawa Rehabilitation Center, the majority of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch between 2011 and 2015 were not transiting anywhere. On the contrary, they were arbitrarily detained for prolonged periods before being released, often in worse physical and psychological condition than when they were arrested. In many cases, there appeared to be no legal basis for their arrest and no indication that their detention was necessary.

By closing Gikondo and ensuring that police and others who committed abuses there are investigated and prosecuted, the Rwandan government would be making an important contribution towards respecting the basic rights of some of Kigali’s most vulnerable residents, who live in daily fear of being sent to the center.

The desire for tidy streets should not lead to human rights abuses against some of Rwanda’s economically and socially most disadvantaged groups. Donors to Rwanda, many of whom praise the cleanliness and order in Kigali, should take a stand against these abuses. They have the responsibility to look beyond the façade and ask a critical question: at what cost order and cleanliness?

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Lewis Mudge, researcher in the Africa Division at Human Rights Watch. It was reviewed by Carina Tertsakian, senior researcher in the Africa Division; Anneke Van Woudenberg, deputy director in the Africa Division; Aisling Reidy, senior legal advisor; and Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director in the program office. This report also benefitted from the editorial review of Agnes Odhiambo, senior researcher in the Women’s Rights Division, and Michael Bochenek, senior counsel in the Children’s Rights Division. John Emerson produced satellite imagery. Production and editing assistance was provided by Lianna Merner, senior coordinator in the Africa Division. Kathy Mills, publications specialist, and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, provided production assistance.

Danielle Serres translated the report into French. Peter Huvos, French website editor, vetted the French translation.

Human Rights Watch wishes to thank the former detainees of Gikondo who spoke about their experiences, sometimes at great personal risk.