Introduction

In our globalized economy, businesses across all sectors increasingly source all manners of goods and services from complex chains of suppliers that often span multiple countries with radically different legal, regulatory, and human rights practices. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), more than 450 million people work in supply chain-related jobs. While complex global supply chains can offer important opportunities for economic and social development, they often present serious human rights risks that many companies have failed to mitigate and respond to effectively.

Individual companies’ global supply chains often involve large numbers of suppliers or subcontractors, including some who are part of the informal sector. The people most affected by human rights abuses in a company’s supply chain often belong to groups who have no realistic opportunities to call attention to these problems themselves, or secure a remedy, such as women workers, migrant workers, child laborers, or residents of rural or poor urban areas.

International norms, such as the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, recognize that companies should undertake “human rights due diligence” measures to ensure their operations respect human rights and do not contribute to human rights abuses. Human rights due diligence includes steps to assess actual and potential human rights risks, take effective measures to mitigate those risks, and act to end abuses and ensure remedy for any that occur in spite of those efforts. Companies should also be fully transparent about these efforts.

But the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and other international norms for companies are not legally binding. Companies can and sometimes do ignore them, or take them up half-heartedly and ineffectively. Many companies have inadequate or no human rights due diligence measures in place, and their actions cause or contribute to human rights abuses. For more than two decades, in every region of the world, Human Rights Watch has documented human rights abuses in the context of global supply chains in agriculture, the garment and footwear industry, mining, construction, and other sectors.

The 2016 International Labour Conference, a global summit of governments, employers, and trade unions on labor issues, presents a unique opportunity to bring about fundamental change. For the first time, the International Labour Conference will focus on decent work in global supply chains. Governments have the primary responsibility to protect human rights, including of people working in global supply chains, but have often failed to oversee or regulate the human rights practices of companies domiciled on their soil. In the absence of legally binding standards, ensuring that all companies take their human rights due diligence responsibilities seriously becomes extremely difficult. Voluntary standards, while valuable, are not enough.

Human Rights Watch urges governments, employers, and trade unions attending the International Labour Conference to seize the opportunity to begin the process for the adoption of a new, international, legally binding standard that obliges governments to require businesses to conduct human rights due diligence in global supply chains.

Recommendations

To Governments, Employers, and Workers at the International Labour Conference

- At the 2016 International Labour Conference, decide to initiate the process for a new, international, legally binding standard that obliges governments to require businesses to conduct human rights due diligence across the entirety of their global supply chains. Such due diligence should include, at a minimum, the following elements:

- Adoption and implementation of a clear policy commitment to respect human rights, embedded in all relevant business functions;

- Identification and assessment of actual and potential adverse human rights impacts;

- Prevention and mitigation of adverse human rights impacts;

- Verification of whether adverse human rights impacts are addressed;

- External communication of how adverse human rights impacts are being addressed; and

- Effective processes designed to ensure that adversely affected people are able to secure remediation of any adverse human rights impacts a business has caused or contributed to.

Human rights violations in the context of global supply chains

For more than two decades, Human Rights Watch has documented human rights abuses in the context of global supply chains. We have interviewed thousands of workers, employers, government officials, and other affected individuals in a variety of sectors in every region of the world. Below are a few select examples that illustrate the most pervasive human rights problems we have found in the supply chains of many companies across sectors in countries around the world.

Labor rights violations

Around the world, millions of people work in global supply chains—for example, in factories producing branded apparel and footwear for consumers worldwide, on farms growing tobacco purchased by cigarette manufacturers, or in small-scale mines digging gold that is destined for the global market. Too many of these workers endure abuses such as poor working conditions, including minimum wage violations; forced overtime; child labor; sexual harassment, exposure to toxic substances and other extreme occupational hazards; and retaliation against workers who attempt to organize. Workers facing these abuses often lack access to complaints mechanisms, whistle blower protections, or legal recourse.

Under international law, governments have an obligation to protect labor rights, including the right to protest and form unions—but many fail to do so. Globally, an estimated 21 million people are victims of forced labor.[1]

The April 2013 Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh put the spotlight on poor working conditions and labor rights abuses in factories producing for global apparel and footwear brands. The eight-story Rana Plaza building was located outside Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka, and housed garment factories that employed over 5,000 workers. The building’s catastrophic collapse killed over 1,100 workers and injured over 2,000. In the wake of the disaster, major apparel brands launched new initiatives to protect the safety of workers in their supply chains. Three years on, Bangladesh has seen concrete improvements on fire and building safety, but apparel and footwear supply chains are still plagued by serious human rights problems. For example, Human Rights Watch has documented how many apparel workers in Bangladesh and Cambodia experience forced overtime, pregnancy-based discrimination, and denial of paid maternity leave. Anti-union abuses are common.Workers attempting to organize in both countries have been threatened, harassed, and dismissed from their jobs in retaliation.[2]

Labor rights violations are also rife in Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and other Gulf States, where construction workers have suffered serious abuse in the context of supply chains in large-scale construction and engineering projects. These low-paid migrant workers face hazardous, and sometimes deadly, working conditions, and are often bound to abusive employers through the kafala (sponsorship) system. Passport confiscation is systematic and many workers arrive with significant debts on account of extortionate recruitment fees, which can take several years to repay. Migrant workers are unable to form or join trade unions, and there is generally little or no possibility of judicial redress for abuse. This combination of control mechanisms can lead all too easily to trafficking and forced labor.[3]

Child Labor

Child labor is still a serious problem in the global economy. Over 168 million children are involved in child labor globally, and 85 million of them are engaged in hazardous work that puts their health or safety at risk.[4] Many child laborers endure physical and psychological abuse, exploitation, and trafficking. In addition, many are denied educational opportunities and are therefore more likely to end up trapped in poverty.[5] Companies may contribute to and benefit from child labor in their supply chains, for example when children harvest export crops, mine precious minerals, process leather, and sew apparel. Under international law, the worst forms of child labor are prohibited, but many governments have failed to take effective steps to end it.

One particularly harmful agricultural crop for children is tobacco. Children who come into contact with tobacco plants risk suffering acute nicotine poisoning. Human Rights Watch has documented hazardous child labor in tobacco farming in the United States and Indonesia, interviewing many children who reported symptoms consistent with acute nicotine poisoning, such as nausea, vomiting, headaches, and dizziness. This tobacco enters the supply chains of major cigarette manufacturers.[7]

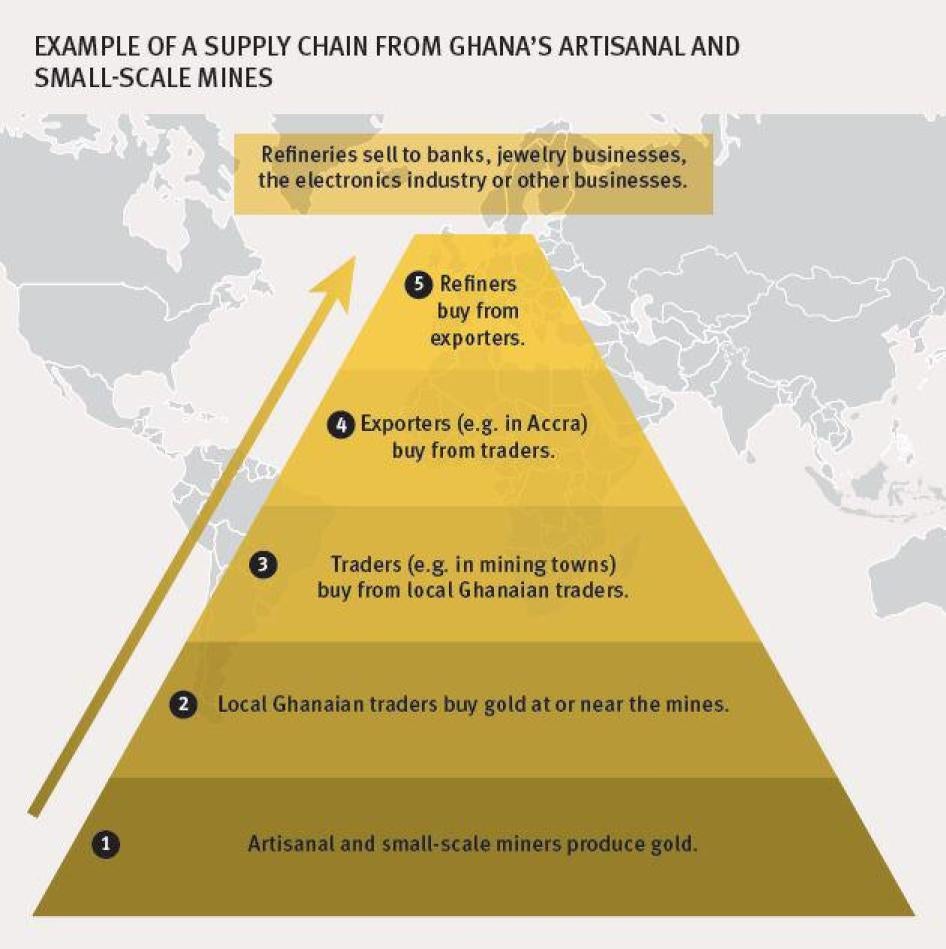

Another highly hazardous form of child labor is mining. An estimated one million children work globally in artisanal mines that generally rely on simple machinery and a large workforce. Approximately 15 percent of the world’s gold originates from artisanal mines. Many children process gold with mercury, a highly toxic substance that causes brain damage and other lifelong health conditions. Child miners also risk their lives when working in unstable pits that frequently collapse. Human Rights Watch has documented hazardous child labor, including the deaths of children working underground, in artisanal gold mining in Ghana, Mali, Tanzania, and the Philippines. Much of the gold produced in these settings finds its way onto the international market.[8]

Environmental damage and violations of the right to health

Through their global supply chains, many businesses risk contributing to the more than 12 million deaths that are attributable to unhealthy environments each year.[9] International norms and many domestic legal frameworks set out government obligations to protect the right to environmental health, but these are often ignored or inadequately enforced.

For example, in the Hazaribagh neighborhood of Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka, around 150 tanneries—many of them producing leather as raw materials for the products of big name brands— expose workers and local residents to untreated tannery effluent that contains chromium, sulphur, ammonium, and other chemicals that cause serious health problems.[10] Government officials, tannery association representatives, trade union officials, and staff of nongovernmental organizations all told Human Rights Watch that no Hazaribagh tannery has an effluent treatment plant to treat its waste. Tannery workers described and displayed a range of health conditions including prematurely aged, discolored, itchy, peeling, acid-burned, and rash-covered skin; fingers corroded to stumps; aches, dizziness, and nausea; and disfigured or amputated limbs. The output of Hazaribagh’s tanneries makes up around 90 percent of Bangladesh’s total leather production, most of which is for export.[11]

Many mining operations have also caused ill-health and environmental damage. For example, in 2011, Human Rights Watch looked at how the Porgera mine (of Barrick Gold, a Canadian global mining company) in Papua New Guinea was dumping 14,000 tons of liquid mining waste daily into a nearby river, potentially causing environmental damage and ill-health to downstream communities.[12] Similarly, Human Rights Watch found that small- and medium-scale iron mines in India had destroyed or contaminated water sources that residents depended on for drinking water and irrigation in two states. Indian legal and regulatory frameworks meant to prevent such harms were hobbled by weak institutional capacity and a basic lack of political will to implement regulations. A large proportion of iron ore mined in India is destined for the international market.[13] Artisanal and small-scale gold miners in many countries use mercury to process gold, emitting more than 700 tons of this toxic metal annually, and causing mercury poisoning in many small-scale miners.[14]

Violations of the rights related to land, food, and water

Communities have suffered human rights abuses when companies acquire land for large-scale mining, agribusiness, or other commercial enterprises linked to global supply chains. The rights of whole communities can be at risk in the context of large-scale land deals, with women often facing distinctive and additional risks.

Under international law, the rights to water, food, and housing are protected. Governments are obligated to take steps to progressively realize full access to these rights over time. Yet, when local communities have been resettled to make way for commercial enterprises, their access to water and their ability to grow their own food has sometimes been impeded, with particularly severe impacts on women. For example, when communities were resettled to make way for large-scale coal mining operations in Mozambique, they were pushed into unacceptable new living situations that led to violations of their rights to water and to food.[15]

Indigenous communities are in a particularly vulnerable situation in the face of large commercial land acquisitions because their culture and livelihood is tied to their land. Under international law, governments or companies seeking to work on land where indigenous peoples live often have a responsibility to seek their free, prior, and informed consent before moving forward. But this right has been widely disrespected. Human Rights Watch found that mining companies in Uganda, for example, have failed to secure free, prior, and informed consent from indigenous communities before they started exploration; similarly, the government of Ethiopia has cleared land for the purposes of export-oriented commercial agriculture without seeking free, prior, and informed consent from indigenous peoples.[16]

Violations of International Humanitarian Law

Companies have caused, contributed, or been directly linked to violations of international humanitarian law (also known as the laws of war) in situations of armed conflict or military occupation.

For example, during the height of the armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo, AngloGold Ashanti—a leading gold mining company—established relations with the Nationalist and Integrationist Front, an armed group responsible for serious human rights abuses including war crimes and crimes against humanity. In return for the armed group’s assurances of security for its operations and staff, AngloGold Ashanti provided logistical and financial support to the armed group and its leaders. In this way, the company may have contributed to serious human rights abuses carried out by that armed group.[17]

Another example is the role of businesses with operations linked to Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank. These businesses contribute to Israel’s violations of international humanitarian law and human rights abuses that dispossess and discriminate against Palestinians. In particular, they facilitate the presence and growth of settlements and contribute to Israel’s unlawful confiscation of Palestinian land and other resources. They also benefit from abusive government policies that discriminate against Palestinians by virtually barring Palestinian economic and residential development in 60 percent of the West Bank.[18]

Why A Binding Global Standard on Human Rights Due Diligence Is Needed: Companies’ Lack of Adequate Rights Safeguards in Supply Chains

Lack of state action: Governments do not regulate business enough

The primary responsibility for upholding human rights lies with governments. In order to protect human rights, governments have a duty to effectively regulate business activity and to put in place and enforce robust labor laws, in line with International Labour Organization (ILO) standards. In practice, Human Rights Watch research has found that loopholes in labor law, weak labor inspections, and poor enforcement often undermine labor rights and other human rights.

Governments also should oversee and regulate business human rights practices domestically and abroad. While governments do generally regulate company behavior at the domestic level, they do so with varying degrees of seriousness and effectiveness. And governments have consistently failed to oversee or regulate the extraterritorial human rights practices of companies domiciled on their soil. In the absence of legally binding standards, ensuring that all companies take their human rights due diligence responsibilities seriously becomes extremely difficult. While some companies may take their human rights responsibilities seriously and implement robust human rights due diligence, their competitors may decline to take any such steps and may suffer no adverse consequence. Even companies that do voluntarily undertake human rights due diligence can benefit from strong practical guidance in the form of reasonable government regulation.[19] A new, international, legally binding standard on human rights due diligence in global supply chains would be a major step towards enhancing responsible businesses around the world.

Where states have imposed mandatory human rights due diligence, company transparency has improved. This has been for example the case of the Dodd Frank Act, a United States law requiring companies to publicly report on the extent to which they have conducted due diligence to ensure their mineral supply chains do not fuel armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo.[20] In 2015, the Modern Slavery Act entered into force in the United Kingdom, obliging companies to report annually on steps taken to ensure that neither slavery nor human trafficking exist in any part of their business operations or supply chains.[21] While it is too early to judge the full impact of the law, it has the potential to increase transparency about companies’ efforts to avoid the involvement of modern slavery or trafficking in their supply chains. Brazil is an interesting example of a country producing for the global market where legal requirements imposed on foreign companies sourcing tobacco have helped prevent child labor, coupled with other government measures. (See text box).

|

STEP IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION: GOVERNMENT REGULATION OF BUSINESS How governments can oblige businesses to conduct due diligence: Brazil’s measures to eliminate child labor in tobacco farming Brazil, the world’s second-largest tobacco producer, has taken steps to enforce a ban on child labor in tobacco farming and hold both farmers and businesses in the supply chain accountable for violations of that ban. Because of the hazardous nature of tobacco farming, Brazil has prohibited all work by children under 18 in the crop and established penalties severe enough to dissuade farmers from allowing children to work in this sector. Penalties under Brazilian law apply not only to farmers, but also to companies purchasing the tobacco, creating an incentive for the tobacco industry to ensure that children are not working on farms in their supply chains. Human Rights Watch research found that companies’ contracts with farmers generally included an explicit ban on child labor, and provided for financial penalties if children were found working. Companies also made a point of sending “instructors” to visit farmers several times during each tobacco season to remind farmers that child labor was prohibited. Recognizing that bans are not enough to eliminate child labor, Brazil has also put in place social programs for poor families to help alleviate the financial desperation that drives parents to send their children to work. Though not a perfect system, Brazil’s approach to child labor provides an example of how governments can address child labor in supply chains. Brazil’s example could inform policy decisions in other tobacco-producing countries, where such steps have not been taken.[22] |

The role of the ILO in setting binding standards in global supply chains

The ILO is well-placed to initiate the process for a new, international, legally binding standard on human rights due diligence in supply chains. The ILO’s tripartite structure brings together workers, employers, and governments. ILO Conventions have helped advance the protection of workers’ rights globally. In recent years, the ILO has also taken up the issue of supply chain due diligence. Together with the International Finance Cooperation, the ILO has set up the Better Work program, a mechanism to monitor working conditions in the apparel sector.[23] The 2014 ILO Forced Labor Protocol—which is not yet in force—also requires parties to “support due diligence” to prevent forced labor.[24]

The ILO should therefore take the lead in bringing about an international, binding standard on human rights in global supply chains.

A voluntary standard on human rights due diligence: The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights

The human rights responsibilities of businesses are spelled out in a number of non-binding international standards, including the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and several sector-specific OECD guidance documents.[25] A new international legally binding standard on human rights due diligence in global supply chains should draw on these widely accepted standards, building on the concept of human rights due diligence put forward in the UN Guiding Principles (as well as the OECD standards).

Under the UN Guiding Principles, businesses should ensure that they respect human rights in their own activities as well as through their business relationships in supply chains.

The UN Guiding Principles define safeguards—including so-called human rights due diligence measures—that companies should have in place to identify, mitigate, and respond to human rights risks throughout their supply chains.

Specifically, the UN Guiding Principles urge companies to:

- Implement a clear policy commitment to respect human rights, embedded in all relevant business functions.

- Develop a human rights due diligence process that should:

- Identify and assess actual and potential adverse human rights impacts;

- Prevent and mitigate adverse human rights impacts;

- Verify whether adverse human rights impacts are addressed; and

- Communicate externally how adverse human rights impacts are being addressed.

- Ensure adversely affected people are able to secure remediation of any adverse human rights impacts a business has caused or contributed to.[26]

While some businesses have made progress to put the UN Guiding Principles into practice, the standard’s voluntary nature leaves companies free to shirk their responsibilities without consequence. Even companies that have made good faith efforts to live up to their human rights responsibilities have often failed to do so, partly because they lack the sound guidance they need in the form of strong government regulation. Far more needs to be done. Below are examples of poor implementation of the UN Guiding Principles, in particular weak company policy commitments, human rights due diligence, and remediation efforts.

Companies’ Lack of Adequate Human Rights Safeguards in Supply Chains

Weak human rights policy commitments and action

Under the UN Guiding Principles, businesses should have a clear human rights policy that spells out how the company will seek to respect human rights. But many company policies either fail to do this or are not adequately implemented.

Human Rights Watch has also found that companies sometimes lack specific child labor policies, even though child labor occurs in the countries they source from. For example, at the time of Human Rights Watch’s documentation of child labor in tobacco farming in the US in 2013, some tobacco companies did not have any child labor policies at all, and defaulted to weak protections in US labor law.[28]

Insufficient assessment and monitoring of risks of human rights abuses

Companies should take steps to ensure that they know what the risks of human rights violations in their supply chain are, and should monitor and address those risks on an ongoing basis. In order to correctly assess risks in their supply chain, companies need to be familiar with every link in their supply chain.

In practice, businesses often fail to get a clear picture of the human rights risks contained in their supply chain. Some companies do not even map out all actors involved in their supply chain.

For example, several international gold refineries have bought from Ghanaian gold export companies that had not traced the origin of the gold they were selling on and did not have sufficient child labor due diligence in place. One of the Ghanaian export companies acknowledged to Human Rights Watch that “we have no way of knowing… whether the gold is from child labor.”[29]

Failure to adequately assess human rights risks can also contribute to violations of international humanitarian law, or the laws of war. For example, an American retail chain sourced linens from a manufacturer, which was located in an Israeli settlement industrial zone in the occupied West Bank before relocating to Israel in October 2015. Until then, the retail chain imported the settlement-produced goods, thereby contributing to and benefitting from Israeli settlement activity in occupied Palestinian territory, which violates international humanitarian law. The company also contributed to and benefited from human rights abuses associated with the occupation. The manufacturer promoted itself on its website as an exporter with a “home-base in Israel” and labeled the linens as made in Israel, but the retailer—which appears to have known the true origin of the goods—failed in its duty to conduct due diligence to ascertain the true origin of the goods and to ensure that it did not contribute to violations of the international humanitarian laws applicable to occupation and human rights abuses.[31]

One method to assess and monitor risks is to conduct inspections at production sites. However, businesses do not always conduct such visits. Companies who visit production sites may also conduct very superficial inspections and give the local employer advance notice. As a result, abuses may not be detected or may be concealed.[32]

Weaknesses in preventing and mitigating human rights abuse

Once companies have identified risks to human rights, they should take steps to prevent or mitigate those risks. Depending on the context these may include putting in place regular surprise inspections, contractual obligations for suppliers, whistleblower protection, and other measures.

Many companies fail to write specific human rights requirements into contracts with their suppliers. For example, most workers in the construction sector in the Gulf States are not covered by meaningful labor protections under domestic law, and most construction firms do not address this gap by insisting their contractors provide adequate rights protections. In some high profile projects in the Gulf States—such as construction associated with the 2022 Qatar World Cup or on Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi—contractual codes of labor protection are in place to regulate the conduct of contractors and subcontractors, but these are exceptions rather than the norm.[33]

Insufficient third-party auditing for human rights issues

Companies across many sectors engage third-party auditors to verify compliance with laws, regulations, and voluntary standards, including on responsible sourcing and respect for human rights. They sometimes also outsource the assessment of human rights risks.

However, Human Rights Watch has found that these audits frequently do not focus strongly enough on human rights, are not conducted by human rights experts, or are too limited in scope.

For example, in the precious minerals industry, voluntary standards for responsible sourcing seek to ensure respect for human rights alongside other goals, but third-party verification of company compliance with these standards has sometimes neglected human rights issues. In one case, Human Rights Watch found that the summary report of an audit against Dubai’s responsible sourcing standard for a gold refinery in the United Arab Emirates did not mention human rights at all, and did not include any site visits to gold mines the refinery was sourcing from.[34]

In the tobacco industry, Human Rights Watch found that in some cases auditors inspected tobacco farms in the US, but the inspections were deeply flawed. Auditors sometimes did not speak the language of the workers, did not interview workers during site visits, visited at times of the day or year when children were not likely to be working, or announced visits ahead of time.[35]

In Bangladesh, weak third-party social audits have been identified as one of the factors that contributed to the Rana Plaza collapse. According to trade unions, such audits often addressed worker’s rights issues superficially or not at all.[36] Since the Rana Plaza disaster, inspection of fire and building safety has improved in the garment and footwear sector, particularly in Bangladesh.

A large auditing company, Ernst and Young, has criticized a “checklist approach” in auditing that is “skewed towards the detection of clerical errors and health and safety questions with yes/no answers” in current social compliance auditing across a variety of sectors and countries.[37]

Lack of adequate external communication and public reporting

All too often, businesses keep the results of their internal and third-party inspections secret or publish only summary audit reports. While some information could legitimately be kept internal, companies should report publicly on the steps they have taken to conduct human rights due diligence. The lack of adequate public reporting poses a serious problem of accountability. If companies do not disclose the steps they have taken to identify, prevent, mitigate, or remediate human rights risks in their supply chain, abuses can be covered up, companies evade public scrutiny, and it is far harder to remedy problems.

One example of weak public external communication is the poor reporting on audits conducted among gold refineries on responsible minerals supply chains. Gold refiners have published summary compliance reports and summary reports of audits against several responsible sourcing standards,[38] but not the full findings. One refinery has not even published the summary report of its audit against the “Responsible Gold Guidance” of the London Bullion Market Association.[39]

Some brands, however, do publicly disclose information about factories that produce for them, enabling better risk assessments. (See text box).

|

STEP IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION: PUBLIC DISCLOSURE OF SUPPLIERS ENABLES BETTER RISK ASSESSMENTS Public disclosure of suppliers in the Garment and Footwear Sector Some leading brands including Adidas, Disney, H&M, Levis, New Balance, Nike, Patagonia, and Puma regularly publish lists of the factories producing their clothes and shoes on their websites. By publishing the names and locations factories producing for the company, companies bolster their ability to prevent and take timely measures to mitigate and remediate labor rights violations in their supply chains. The disclosure of information by some brands in the garment and footwear section is a powerful first step towards greater transparency. |

Insufficient remediation

Where business enterprises have caused, contributed, or been directly linked to rights abuses, they should provide for or cooperate in the remediation of these abuses. But in practice, Human Rights Watch has found a number of instances where businesses have failed to take any effective steps to ensure remedy for human rights abuses that have occurred in their supply chains.[40]

A positive example for remediation, if limited in scope, is the legally binding Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety. (See text box).

|

STEP IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION: PREVENTION, MITIGATION, AND REMEDIATION The legally binding Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety In May 2013, in the immediate aftermath of the Rana Plaza collapse, more than 200 apparel and footwear companies signed a five-year legally binding agreement with trade unions to work towards factory building and fire safety in Bangladesh’s garment industry. This agreement paid attention to the serious flaws in the Bangladesh labor inspectorate regarding building safety, created an independent inspection system, and publicly disclosed all factories covered by the agreement, inspection reports, and corrective action plans. The Accord, even though limited to fire and building safety issues, has been a promising collaborative effort to improve due diligence. |