“How Can We Survive Here?”

The Impact of Mining on Human Rights in Karamoja, Uganda

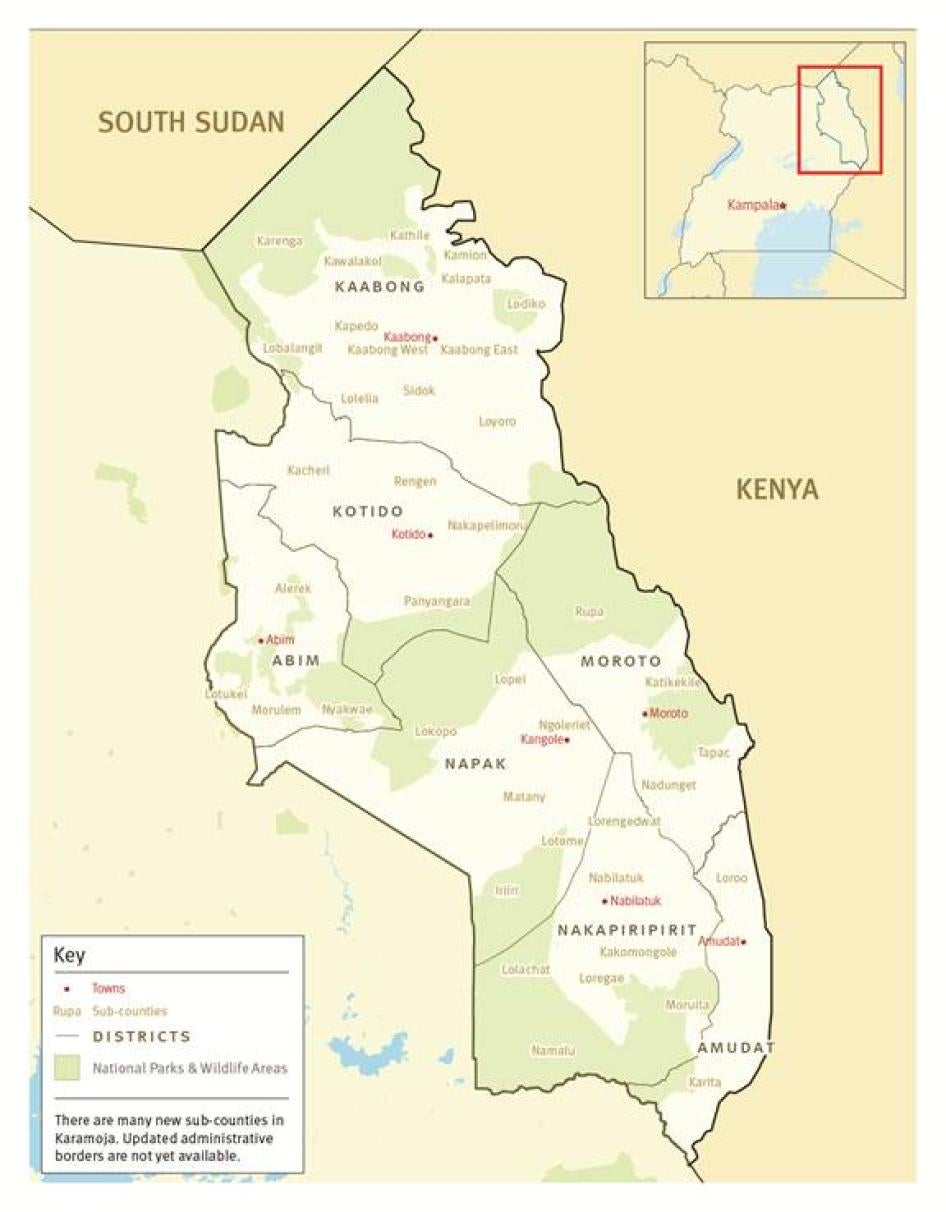

Map 1: Districts and Sub-Counties in Karamoja

© 2014 John Emerson / Human Rights Watch

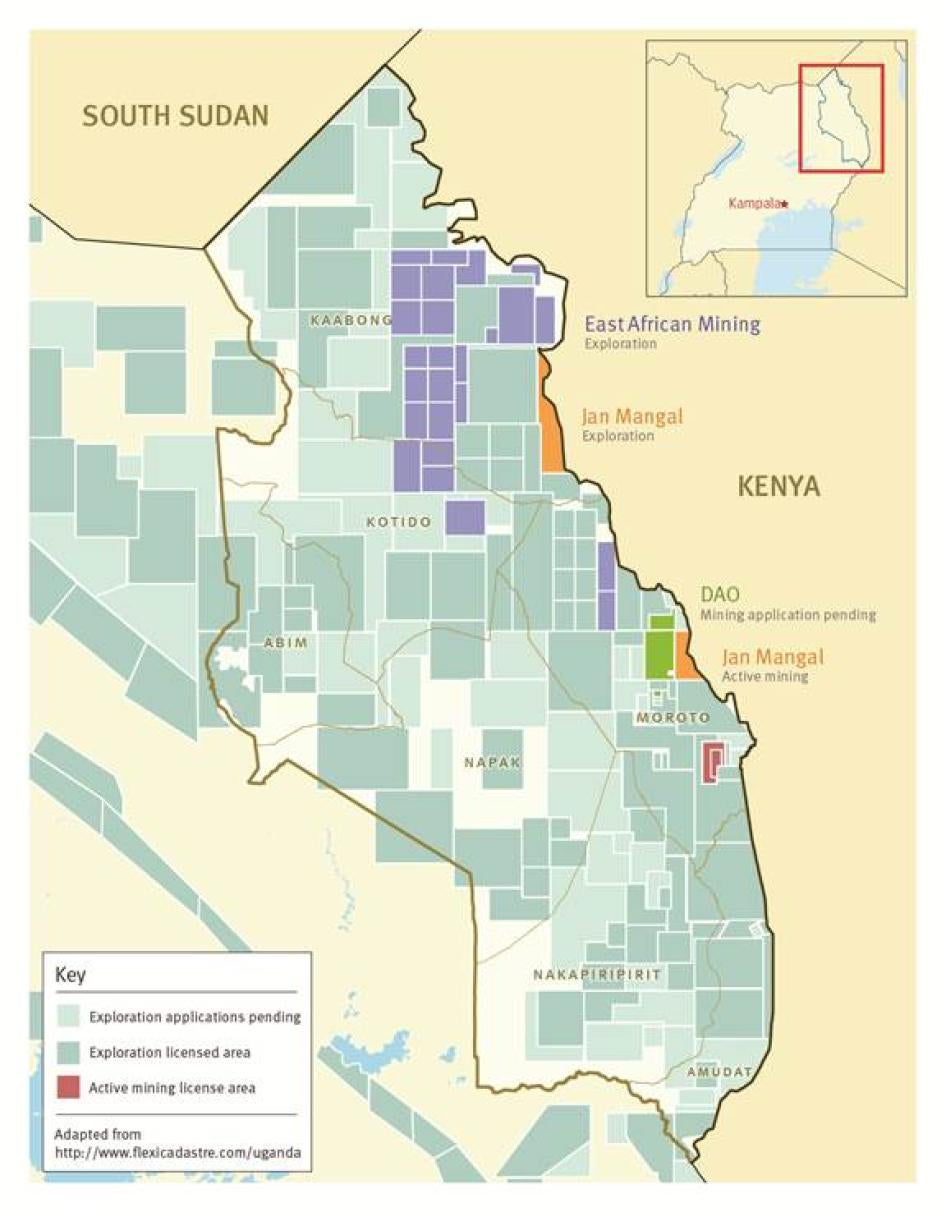

Map 2: Mining Licensing in Karamoja

© 2014 John Emerson / Human Rights Watch

Summary

“There is nothing bad about companies coming, but what we hate is the way they come in, don’t show us respect, and don’t show us the impact and the benefits of their work for my people.”

—Dodoth elder of Sidok, Kaabong town, July 3, 2013

“We want to see our natural resources exploited but our people should not be. Pastoralism lives here, we are pastoralists. The land looks vacant but it is not.”

—Mining community organizer, Moroto, July 7, 2013

Basic survival is very difficult for the 1.2 million people who live in Karamoja, a remote region in northeastern Uganda bordering Kenya marked by chronic poverty and the poorest human development indicators in the country. Traditional dependence on semi-nomadic cattle-raising has been increasingly jeopardized. Extreme climate variability, amongst other factors, has made the region’s pastoralist and agro-pastoralist people highly vulnerable to food insecurity. Other factors include gazetting of land, under both colonial and recent governments, for wildlife conservation and hunting that prompted restrictions on their mobility, and more recently the Ugandan army’s brutal campaign of forced disarmament to rid the region of guns and reduce raids between neighboring groups caused death and loss of livestock.

Uganda’s government has promoted private investment in mining in Karamoja as a way of developing the region since violent incidents of cattle rustling between communities have decreased in recent years. Karamoja has long been thought to possess considerable mineral deposits and sits on the frontier of a potential mining boom. Private sector investment could transform the region, providing jobs and improving residents’ security, access to water, roads, and other infrastructure. But the extent to which Karamoja’s communities will benefit, if at all, remains an open question and the potential for harm is great. As companies have begun to explore and mine the area, communities are voicing serious fears of land grabs, environmental damage, and a lack of information as to how and when they will see improved access to basic services or other positive impacts.

Communities in Karamoja have traditionally survived through a combination of pastoral and agro-pastoral livelihoods, balancing cattle-raising with opportunistic crop cultivation. Communities are usually led by male elders who gather in open-air shrines to make decisions of importance to the community and share information. Land is held communally, with multiple overlapping uses, including grazing, habitation, and migration. Over the last two generations, both men and women have turned to the grueling work of artisanal gold mining for cash in part because of increased weather variability and the loss of livestock due to cattle raiding and the government’s disarmament program. This increases community concerns for how large scale mining will affect their survival and makes the lack of consultation and information with affected communities all the more dire.

Based on more than 137 interviews over three weeks of research in Moroto, Kotido, and Kaabong, three of Karamoja’s seven districts, and two months in Kampala, as well as meetings and correspondence with government officials and companies working in Karamoja, this report examines the human rights impacts of the nascent mining industry in Karamoja. Companies seeking to work in the region have a responsibility to respect human rights, including the land and resource rights of its indigenous peoples. The government has an obligation to respect, protect, and fulfill these rights. This report focuses in particular on the right of indigenous peoples to freely give (or withhold) their consent to projects on their lands, including during mineral exploration.

While Uganda’s mining law requires a surface rights agreement to be negotiated with land owners prior to active mining and payments of royalties to lawful landowners once revenues flow, the law does not require any communication or consent from the local population during exploration work. And despite Uganda’s land laws recognizing customary land ownership, the Land Board has not yet granted any such certificates anywhere in the country. There is considerable governmental resistance to communal or collective land ownership involving large numbers of owners, as is the tradition in Karamoja. The residents’ lack of legal proof of land ownership puts communities in significant jeopardy of rights abuses as mining activities increase. Fears of land grabs, loss of access to mineral deposits, water contamination and erosion, forced evictions, and failure to pay royalties to traditional land owners have already prompted communities to question the companies and their own government’s role in the companies’ operations.

Several extractives companies have come to Karamoja in the past two years seeking natural resources, particularly gold and marble. None of the communities interviewed by Human Rights Watch indicated that they were outright opposed to exploration or mining activities on their lands, but community members repeatedly stressed that there has been inadequate information and participation in decision making and confusion as to how the communities would benefit, if at all. They described not understanding private investors’ intentions and long term objectives, and being unaware of the communities’ rights or companies’ obligations under national laws and international standards. Local governments were similarly uninformed.

The companies have consistently failed to secure free, prior, and informed consent from the local communities before they started operations on communal lands. The central and local governments have failed to insist on this established international standard. Companies have promised communities benefits, including schools, hospitals, boreholes, jobs, scholarships, and money in exchange for their compliance. But often exploration work has continued and communities have yet to see the promised benefits that were supposed to help mitigate current and future loss of land use, livelihood, and other impacts.

This report, in examining three companies currently working in Karamoja and at different stages of the mining process, found that companies have explored for minerals and actively mined on lands owned and occupied by Karamoja’s indigenous peoples. But the Ugandan government, in partnership with the private sector, has excluded customary land owners from making decisions about the development of their own lands and has proceeded without their consent. Legal reforms, to the land and mining act among others, are needed to ensure that the peoples’ right to development is protected as mining escalates.

East African Mining Ltd., the Ugandan subsidiary of East African Gold—a company incorporated in Jersey in the Channel Islands, a British dependency with a negligible company tax rate—obtained exploration licenses from the government of Uganda over more than 2,000 square kilometers of land in Kaabong and Kotido districts in 2012. The company hired a Ugandan team, including a local manager originally from Kaabong. Residents have alleged that, without consultative meetings with the community, they often found exploration teams on their land, taking soil samples from their gardens and even within their homes without any explanation and in some cases, locals indicate, destroying crops in the process. The concession area includes Lopedo, an area prized by local artisanal gold miners who have expressed fears that the company would eventually seek to remove them from the land or destroy their own ability to mine, a key source of livelihood during the dry season. After sub-county officials protested and complained over several months, the company hired a local community liaison manager to try to negotiate with the residents and seek their cooperation. Questions arose about poor local labor practices, friction between the company and both the sub-county and district leadership, and ad hoc, unfulfilled promises have prompted frustration from local residents who told Human Rights Watch that they felt both excluded and exploited by the company’s work. Confusion has persisted since the company suspended exploration operations in early 2013 to secure an infusion of capital.

Jan Mangal Uganda Ltd., a Ugandan subsidiary of an Indian jewelry company, arrived in Rupa sub-county, Moroto district, complete with excavators and other mining equipment in mid-2012 to mine gold. While some high-level government officials and political elites had encouraged this venture, according to local government officials, Jan Mangal senior management, and community members, Jan Mangal arrived without having had any contact with the local government or local community members or even acquiring an exploration license from the central government. When residents protested the company’s presence, a long and puzzling series of negotiations began between the company and the central government, other political elites, and elements of the local government. Several affected community leaders said that they were excluded from discussions.

Eventually, the company secured an exploration license for an area near the communities of Nakiloro and Nakibat in Rupa, Moroto district, along the Kenyan border. With support from the speaker of the local town council, the company transported several individually selected elders to Kampala to discuss Jan Mangal’s project. According to a report about the trip, the elders met with high-ranking central government officials, together with Jan Mangal representatives and the Moroto district speaker, to indicate their support for the granting of a mining lease, required for excavating and processing minerals.

There is great confusion within the community about why these particular elders were selected, what was discussed, and what was agreed during the Kampala trip. Several community members shared the belief that a surface rights agreement was signed in Kampala, but the vaguely worded agreement is dated as having been signed several months in advance of the Kampala trip. Despite the ongoing misunderstandings and inter-communal animosity, that surface rights agreement formed the basis for the company’s application for a mining lease, but community members remain unaware of its content or the signatories of the agreement. Several community members accuse the elders of selling their land. The company has erected a compound for its workers, installed a large gravel sifter on the hill side and commenced mining, pumped water out of a nearby perennial stream, and fenced off the land, blocking community grazing areas.

DAO Uganda Ltd. is the subsidiary of a Saudi and Kuwaiti construction firm. It acquired an exploration license over a few kilometers of land in Rata village, on the border of Rupa and Katikekile sub-counties in Moroto district in 2013. DAO plans to quarry dimension stones which are massive and luxurious marble blocks, ship them to Mombasa, Kenya, and then export them to European and Middle Eastern markets. DAO faced hurdles since, according to community members, it did not get the consent of the local population before beginning exploration. It has now held several meetings to determine which families had households on the land it occupies and paid some compensation to them. This compensation has formed the basis for a surface rights agreement and an application for a mining lease. But tensions over land, employment, and water within the community persist.

In each company concession area, residents consistently complained of lack of consultation and access to information from both the companies and local government officials, particularly regarding employment, land, and possible impacts on the environment. This puts communities’ access to essential resources, such as water, at long-term risk. In the short term, it already has put communities at a serious disadvantage during ad hoc meetings between community members and company representatives that took place after exploration work had begun, often in the presence of central government officials. Some community leaders expressed frustration that they were pressured to submit to company plans, only to beg for benefits, without any way to hold the companies or the government accountable.

While the army specifically denies having any role in the mining sector in Karamoja, there is clear evidence that soldiers provide security for the companies and their workers, and at least in some instances, benefit financially from those arrangements. Given the brutality of the recent forced disarmament in Karamoja, the presence of the military alongside the companies has prompted both apprehension and questions from local residents about intimidation if they try to criticize mining operations or query companies’ decision-making and suspicions of corruption.

Uganda’s mineral industry has grown by an average rate of five percent per year for the past 10 years.[1] There are ample reasons to be concerned about the government’s willingness and ability to protect human rights of indigenous groups in Karamoja as more companies arrive to mine. First, the government’s Department of Geological Survey and Mines (DGSM) has massively accelerated licensing of companies to carry out exploration and mining operations—a more than 700 percent increasebetween 2003 and 2011 country-wide[2]—while its ability to support and educate affected communities, and inspect and monitor the work of companies lags far behind. Local governments also lack the financial resources and technical manpower to effectively monitor mining operations.

Second, successive governments have viewed Karamoja as “backward” and “primitive,” and residents have faced generations of state-sponsored discrimination and externally driven development projects. That discrimination, coupled with the varying levels of insecurity and a general sense that Karamoja is a difficult region in which to operate in terms of both security and infrastructure, has often meant it is the last area to benefit from government policies and donor-funded projects. When the World Bank, the African Development Bank, and the Nordic Development Fund financed a US$48.3 million sustainable mining management project from 2003 to 2011, Karamoja was specifically excluded because of security concerns. This was not remedied when providing additional financing in 2009, even though security had improved and the Ugandan government was increasingly handing out exploration licenses to mining companies and speculators across Karamoja.

Third, the government’s opaque approach to the development of the oil sector on Uganda’s western border bodes ill if it is replicated in Karamoja’s mining sector. There, the controversial resettlement of residents to make way for an oil refinery, on-going allegations of corruption, and the persistent government attacks on civil society critiquing development projects—characterizing them as “economic saboteurs”—raise serious doubts about whether the government and companies will respect human rights as mineral exploration and exploitation progresses in Karamoja.

States have a duty, and companies have a responsibility, to consult and cooperate with indigenous peoples in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources. This right, which is derived from indigenous peoples’ right to own, use, develop, and control their traditionally occupied lands and resources, has been affirmed by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR). But with government and companies providing little information about planned exploration or mining activities and their rights to them, and with scant formal education, the people of Karamoja have barely had a chance to express their views on the mining exploration work. The absence of land tenure registration or security renders communities increasingly vulnerable to abuse.

International donors have played a prominent role in supporting Uganda’s development of the mining sector, but so far projects have excluded indigenous rights and therefore failed to set a positive precedent that would have supported the rights of the people of Karamoja. For example, the World Bank-led multi-donor sustainable mining project did not come close to addressing indigenous peoples’ rights, including the key requirement that all mining projects, including exploration, may only take place with the free, prior, and informed consent of the indigenous land owners.

The Ugandan government should uphold international standards by reforming its laws to ensure that the free, prior, and informed consent of affected communities is required before exploration operations begin and throughout the life of a project. It should also ensure that companies prepare human rights impact assessments carefully and meaningfully to analyze the consequences of their work. It should address the allegations of corruption and bribery and the unclear role of the Ugandan army in providing security for private companies in the region. Current and future investors should live up to their human rights responsibilities by consulting and negotiating with indigenous peoples in order to obtain free and informed consent prior to commencing any project affecting their lands or resources, identify and mitigate risk of future violations of human rights, such as of the right to water and a healthy environment, and investigate and remedy any violations.

Human Rights Watch urges Uganda’s donors, including the World Bank, to address the complex development challenges created by the increased mining operations in the impoverished Karamoja region by pressing the government to create a robust regulatory regime which ensures respect for the rights of the region’s indigenous peoples and improve its monitoring and enforcement capacity. Should mining in Karamoja boom without significant changes in this regard, mining is likely to become yet another obstacle for development in the region, as well as a potential driver of conflict, and prompt increased dependence on outsiders for residents’ survival.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Uganda

- Recognize the communities in Karamoja as indigenous peoples and recognize their rights over land traditionally occupied and used.

- Urgently implement a land tenure registration system that increases security of ownership, particularly for communal land owners.

- Implement robust procedures to consult with the peoples of Karamoja, working transparently through their own representative institutions and local governments in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to approving or commencing any project affecting their lands, including granting exploration licenses and mining leases.

- Expand Uganda’s existing legal requirement to conduct environmental impact assessments (EIAs) to bring it in line with international best practices for comprehensive and transparent social and environmental assessments that explicitly address human rights considerations and are independently verifiable.

To Uganda’s Parliament

- Amend the constitution to recognize indigenous peoples’ rights in line with international human rights law and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, as applied by the Working Group on Indigenous Populations/Communities.

- Amend the Land Act to make eligible broad social representation in the composition of Communal Land Associations legally permissible in order to address a major hurdle for registering certificates of customary ownership. Maintain the current requirement for representation of women, and also require account to be taken of the interests of youth, the elderly, persons with disabilities, and all vulnerable groups in the community.

- Amend the Mining Act to include a requirement for clear evidence of free and informed consent from affected communities prior to the granting of exploration licenses, and again prior to the granting of mining leases.

- Amend the Mining Act to include a requirement for a human rights impact assessment, detailing the potential impacts exploration and active mining may have on affected communities and their rights, what steps companies will take to continually inform and communicate with affected communities, and how adverse rights impacts will be mitigated or avoided.

To Companies Working or Considering Working in Karamoja

- Implement vigorous procedures to consult with the indigenous peoples of Karamoja through their own representative institutions and local governments in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to commencing any project affecting their lands, including exploration or mining.

- Fully uphold internationally recognized human rights responsibilities, including the responsibility to respect human rights and avoid causing or contributing to any abuses.

- Undertake human rights impact assessments to identify potential human rights impacts and avoid or mitigate adverse impacts, in active consultation with the affected community, human rights organizations, and other civil society organizations, and make them publicly available in a timely and accessible manner.

To Uganda’s International Donors, including the World Bank

- Undertake human rights due diligence for proposed development projects to avoid contributing to or exacerbating human rights violations. Only approve projects after assessing human rights risks, including risks concerning land and labor rights; identifying measures to avoid or mitigate risks of adverse impacts; and implementing mechanisms that enable continual analysis of developing human rights risks and adequate supervision.

- Require respect of the right of indigenous peoples to freely give (or withhold) their consent to projects on their lands and urge the Ugandan government publicly and privately to protect this right through its laws, policies, and practices.

- Publicly and privately urge the Ugandan government to amend the Mining Act and the Land Act, as stated above.

An Action Plan for Free, Prior, and Informed Consent in Karamoja

The government, businesses, donors, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) all have a key role to play in working to respect and protect the rights of the peoples of Karamoja as the mining sector builds. This action plan outlines how each of these sectors can advance realization of international standards that require consultation with traditional land owners to seek their free, prior, and informed consent prior to commencing projects on their lands.

States have a duty under international law to consult and cooperate with indigenous peoples through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent. This is supposed to occur before the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization, or exploitation of mineral, water, or other natural resources. [3] This duty is derived from indigenous peoples’ land and resource rights. States must also provide effective mechanisms for just and fair redress for any such activities, and appropriate measures shall be taken to mitigate adverse environmental, economic, social, cultural, or spiritual impact. [4]

While the obligation to carry out these consultations and prevent works without community consent lies primarily with the Ugandan government, businesses also have the responsibility to respect these and related rights. As the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples has emphasized, “Companies should conduct due diligence to ensure that their actions will not violate or be complicit in violating indigenous peoples’ rights, identifying and assessing any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts of a resource extraction project.”[5] In so doing, companies and the government will be taking much-needed steps to avert communal conflict, respect human rights, and provide meaningful and sustainable development for marginalized communities.

Support communities in Karamoja to craft their own development plans: Indigenous communities should be supported and given the opportunity to proactively chart their community’s own course for development. This becomes increasingly challenging when negotiations are happening with companies on a case-by-case basis. NGOs and donors should provide the relevant legal and technical support to communities in discussing their development needs and avenues for achieving them, with the potential of crafting a sustainable development plan for the community. Decisions made through this process can then provide the basis on which community representatives can commence negotiations with mining and other companies interested in doing business on their land.

Inform communities of projects prior to commencing any operations, including exploration, on their lands: The government should consult the peoples of Karamoja and obtain their consent to any proposed projects on their land. Uganda’s Department of Geological Survey and Mines (DGSM) should only grant exploration licenses after it is satisfied that traditional land owners have been fully informed of the exploration proposal, understand the potential environmental, social, and human rights impacts, understand what benefits they will receive and when, and have agreed to the proposal having had the opportunity to reject it. Similarly, companies should consult with communities prior to commencing exploration, making sure that the affected communities are part of every step of the extractive process.

Consult and cooperate with peoples of Karamoja through councils of elders, women caucuses, and youth caucuses: States and companies should consult indigenous peoples through their own representative institutions. For the peoples of Karamoja one primary institution is the council of elders. In addition, informal caucuses of women and youth exist. While the views of these caucuses should be filtered into the community’s decisions through the council of elders, inclusive consultations directly with the caucuses is also essential.

Ensure that all processes are inclusive of women, persons with disabilities, youth, and any other marginalized members of the community: There is a real risk that women and other marginalized groups may not be included in a community’s decision-making process. All actors, including the government, companies, NGOs, and donors, should take affirmative steps to ensure that such groups are fully informed and able to participate freely in decision-making processes.

Together with the councils of elders, caucuses of women, and caucuses of youth, hold public community meetings in all affected communities to disburse information: Public meetings are an important element of the peoples of Karamoja’s decision-making processes. As an elder explained:

In the village, we reach our decisions communally. We have meetings to discuss [problems in the community, for instance] if hunger strikes or there is a disease, and we decide what to do. We meet … and send messages so everyone can come.[6]

Ensure that the community is given the opportunity to approve (or reject) the proposed project prior to the commencement of any operations, including exploration: It is essential that the community be empowered to make the decision of whether or not they want the project to begin, having considered all relevant information.[7] That said, none of the communities interviewed by Human Rights Watch indicated that they were outright opposed to exploration or mining activities on their lands. Rather, the emphasis was on the need for adequate information and participation in decision making. As one elder explained:

People would not refuse as long as we agree what we really want and they agree what they [the company] want from us…. We could only give a portion [of our land], not the whole area. We would need to keep part of the land for our cultivation, part of the land for our animals to graze…. It would be essential that the land could and would be rehabilitated.[8]

Should the community consent to exploration, it must again be given the opportunity to approve (or reject) a proposal to actively mine.

Ensure that the community is given all of the information it needs in order to reach its decision, including independent information and advice: Both the government and companies should provide information about what activities they plan to undertake; the potential impacts on the environment and community members’ human rights, particularly their livelihood, their security, and any cultural or spiritual impacts; and the degree to which adverse impacts can, and will be, avoided or mitigated. Companies should inform communities about companies’ security arrangements, employment opportunities, labor conditions, grievance mechanisms, and how and when the community may expect to benefit. Further, a community’s “consent” cannot be “informed” if the sole source of information is the company that wants to exploit resources on their land. The Uganda Human Rights Commission (UHRC), NGOs, and donors have an important role to play in ensuring that communities are informed of their rights, relevant laws, and have access to independent legal advice.

Undertake and disseminate human rights impact assessments (HRIAs): An HRIA is the key tool for governments, companies, and donors to analyze the likely impacts of proposed activities on human rights, including the rights of indigenous peoples. The Ugandan government should model the system currently used for environmental impact assessments where there is a roster of independent experts from which companies must select. The government should require companies to finance an independent human rights expert, for example from a list maintained by the Uganda Human Rights Commission, to undertake HRIAs both prior to exploration and prior to active mining. Such an assessment should be developed in active consultation with the affected community, human rights organizations, and other civil society organizations, and be made publicly available in a timely and accessible manner. It should be undertaken in conjunction with an environmental impact assessment. The UHRC has an important role to play in ensuring that the requisite standards of human rights impact assessments are met.

Ensure that the community is given the opportunity to participate in setting the terms and conditions that address the economic, social, and environmental impacts: Once the community is properly informed, it has the right to be actively involved in setting the various terms and conditions which they require to grant their consent.

Ensure that the community reaches its decision free from force, manipulation, coercion, or pressure: Both the government and companies have the potential to exert significant pressure on the peoples of Karamoja to acquiesce to mining ventures quickly. The central government’s persistent allegations that opposition to development projects is “economic sabotage” undermine the freedom of communities to reach a decision regarding whether or not to consent to a project on their land. In this environment, it is all the more crucial that companies and local government entities take additional measures to enable communities to reach their decision freely and to respect that decision, and that donors and the international community more broadly pressure the Ugandan government to cease such rhetoric and harassment of affected communities and civil society.

Continue to consult and provide information throughout all phases of operations, from exploration, to extraction, to post-extraction: The duty to consult and cooperate with the peoples of Karamoja in order to obtain free, prior, and informed consent exists throughout the project cycle, requiring companies and the government to keep the community adequately informed throughout.

The government should ensure that the community’s decision is respected: The DGSM, the local government, and the UHRC should monitor the implementation of any terms and conditions agreed to by the company and the community, to ensure that the community’s decision is respected.

Companies should create accessible, independent grievance mechanisms in line with international standards: Companies should put in place effective mechanisms that allow community members to complain directly to senior management to ensure that senior management is made aware of problems along the management chain, particularly when those problems may relate to their senior staff.

Methodology

This report is based on research carried out by Human Rights Watch staff from May to November 2013 in Uganda. Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews in Lodiko, Loyoro, East Kaabong, and Kathile sub-counties and Kaabong town in Kaabong district; Rupa and Katikekile sub-counties and Moroto town in Moroto district; Kotido district; and Kampala and Entebbe.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 61 community members (41 men and 20 women and girls) who lived in the exploration and mining license areas of the three companies featured in this report. The companies are East African Mining Ltd., the Ugandan subsidiary of Jersey-registered East African Gold, Jan Mangal Uganda Ltd., a Ugandan subsidiary of an Indian jewelry company, and DAO Uganda Ltd., the Ugandan subsidiary of a Saudi and Kuwaiti construction firm.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 21 members of the local governments of Moroto and Kaabong districts. Interviews with government officials and company representatives were conducted in English. The vast majority of interviews in the communities were conducted in Ngakarimojong, the language of the peoples of Karamoja, also sometimes spelled N’Karamojong, with translation into English. Some were conducted in Kiswahili.

Human Rights Watch researchers discussed with all interviewees the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, the ways the information would be used, and that no compensation would be provided for participating. Interviews typically lasted between 30 minutes and over one hour. Where necessary, names have been withheld or replaced by randomized initials in order to protect identities. In some cases, useful identifying information was included, such as referring to an individual’s role as a district government official. Footnotes include as much information as possible regarding the interview location, such as listing the parish, sub-county, and district where applicable.

Human Rights Watch also conducted in-person interviews in Uganda with Minister of State for Mineral Development Hon. Peter Lokeris, who is a parliamentarian representing a constituency in Karamoja, and four other parliamentarians from Karamoja, the acting commissioner of the Department of Geological Surveys and Mines (DGSM), a commissioner of the Land Board, as well as over 30 representatives of national and international nongovernmental organizations, United Nations agencies, the World Bank, donor governments, soldiers of the Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces, gold traders, lawyers, journalists, and other persons with knowledge of Karamoja and mining in Uganda.

Additional information for this report was gathered from August to November 2013 via phone and in-person interviews in Kampala, letters, email, and desk research.

Human Rights Watch met with employees of the three companies and then sent letters to each of the company’s senior management. In one instance, Human Rights Watch had a phone interview with the company’s chief executive officer after he expressed a willingness to discuss our research. All correspondence is available in the annexes to this report, though no company responded to the letters in writing.

This report also draws on synthesis and analysis of licensing data collected from

Uganda’s online mining cadaster throughout 2013. Map demarcations of licensing areas are current as of December 2013. Background research included analysis of Uganda’s legal framework, review of existing literature, and press monitoring.

Throughout the report, we use the term “peoples of Karamoja” to refer to the multiple unique ethnic groups living in the region as opposed to “Karamojong.” Experts have reduced their usage of “Karamojong” to refer to all people living in Karamoja because of increased recognition that the region is inhabited by numerous different groups with a diversity of culture and customs. The term is also often confused with “Karimojong,” which refers specifically to the Matheniko, Bokora, and Pian people. All groups in Karamoja face discrimination and political marginalization to varying degrees.

A note on administrative structure: Uganda is currently divided into 120 districts, though 16 more are set to be phased in by July 2015. Starting at the village level (known as Local Councilor 1 or LC1), the local council system progresses up from the parish (LC2) to the sub-county (LC3), county (LC4), and district (LC5), though there are vacancies in some areas of the countries for some positions, particularly LC4s. Councilors are elected. The councils at the county and district level (LC4 and LC5) are local government and have financial, legislative, and administrative powers. The lower level councilors have administrative powers only. The numbers of officials on each council depends on the population of the area.[9] The LC5 is the highest ranking elected district official in each district. Districts have a chief administrative officer (CAO) and a deputy chief administrative officer (deputy CAO) who are unelected civil servants in charge of financial management. They are most often not native to the areas in which they serve and are frequently transferred around the country. Most districts also have a natural resources officer, though some have vacancies. Each district also has a resident district commissioner and a deputy, both appointed directly by the president, who are officially charged with “security matters.”

I. Poverty and Survival in Karamoja

The remote Karamoja region of northeastern Uganda, stretching across 10,550 sparsely populated square miles, accounts for nearly 10 percent of the country.[10] It is home to an estimated 1.2 million people spread across seven districts—Abim, Amudat, Kaabong, Kotido, Moroto, Nakapiripirit, and Napak.

While the ethnic groups who live in Karamoja are sometimes referred to collectively as Karamojong,[11] the majority constitute three distinct large groups: the Dodoth to the north in Kaabong district; the Jie in the center in Kotido district; and the Karimojong (comprised of the Matheniko, Bokora, and Pian) to the south in Moroto and Nakapiripirit districts.[12] Other smaller groups include the Pokot, Ik, Tepeth, and Labwor.[13]

Livelihoods, Marginalization, and Discrimination

The peoples of Karamoja traditionally survive largely through a combination of pastoralism, agro-pastoralism, livestock-herding, and opportunistic agriculture to maximize the unfavorable environmental conditions and low annual rainfall.[14]They occupy semi-permanent manyattas, the center of agricultural livelihoods, while cattle are traditionally kept in mobile or semi-mobile kraals. Failed or poor crops have occurred approximately one out of every three years, making livestock products an essential source of sustenance.[15] Migration is a key element of this livelihood, allowing for the movement of herds between pasture areas in response to environmental pressures. Movements by some groups reach into Kenya and neighboring regions of Uganda.[16]

Traditional livelihoods in Karamoja have been radically altered for most residents due to a variety of external factors. Access to grazing land outside of and between sections of Karamoja has been restricted over time by government policy beginning in the colonial period, including the imposition of a fixed border between Uganda and Kenya,[17] and continuing in the post-independence era.[18] Conflict between groups within Karamoja beginning in the late 1970s has also curtailed internal grazing areas.[19] While livelihood strategies vary across Karamoja and groups engage in livestock keeping, agriculture, and other economic activities to differing degrees often reflecting underlying ecological and historical differences,[20] the peoples of Karamoja regard themselves as cattle keepers. Livestock herding is essential to both cultural identity and livelihood.[21]

While sharing much in common with neighboring groups in Kenya and South Sudan,[22] the pastoralism of Karamoja and its cyclical migrations of people and livestock is largely unique within Uganda. Policies of colonial administrations and post-independence regimes alike have tended to marginalize pastoralism: government initiatives have been directed historically almost wholly toward increasing the sustainability of settled agriculture and the assertion of central control.[23] Some argue these initiatives, including animal confiscations and restrictions on mobility,[24] contributed to the present impoverishment of Karamoja by increasing competition over scarce, degraded resources, which in turn amplified the consequences of devastating droughts.[25]

Society in Karamoja is organized through territorial groupings and kinship clusters with reliance on traditional elders for leadership and decision-making and each ethnic group, such as the Dodoth in Kaabong or the Matheniko of Moroto, has its own leadership. Kraals have elected leaders, but most governing and decision-making among the people of Karamoja are determined by a complex system of elders who hold political authority, though how this arrangement differs among the groups.[26]

Successive Ugandan governments have viewed Karamoja as “backwards” compared to the rest of the country, largely because of the reliance on agro-pastoralism. The Idi Amin regime subdued the region by force, and subsequent former Prime Minister Apolo Milton Obote—famously quoted as having said “We shall not wait for Karamoja to develop”—created the Karamoja Development Agency to try to tackle development in the region. Government pressure to modernize and transform Karamoja continues in current political discourse.[27] In March 2009, when President Yoweri Museveni appointed his wife, Janet Museveni, as minister of state for Karamoja, he spoke of the need to “develop one of the backward areas” of Uganda.[28] Mrs. Museveni herself has spoken of needing to transform “the primitive and poor quality” lives in Karamoja.[29]

The belittling of pastoralism is a recurrent theme in official government statements about the region. The Office of the Prime Minister, currently leading development efforts, has said Karamoja was “a complete write-off, insecure, gun-infested, hunger-prone, derelict and very backward region.”[30] In a letter to the European Union delegation to Uganda in November 2010, Mrs. Museveni highlighted that “the nomadic way of life is ‘outmoded’,” and her office has pushed for development partners to support the government’s program to “stop nomadism and settle permanently because that is the Government’s focus for now.”[31]

The discriminatory language has had a negative impact on some efforts to mitigate local conflict. An April 2013 assessment on conflict management in Karamoja by Mercy Corps— an international development organization that provides support to people after conflict, crisis, and natural disaster world-wide—reported that, due to the treatment by government officials and other security personnel of the people of Karamoja. Elders withdrew from government-led initiatives because “the lack of respect displayed by government actors had … undermined their authority.”[32]

Despite government efforts to centrally control the peoples of Karamoja and “transform” their traditional lifestyle, infrastructure and services in the region, including schools, health centers, potable drinking water, roads, and many other facilities, are scarce.[33] Large swathes of Karamoja are not yet on the national power grid.[34]

Poverty, Food Insecurity , and Artisanal Mining

“Famine has killed many people in this place. Drought has dried the crops. Even wild animals are suffering.”

—“Achilla”, community member, Nakiloro, Rupa, Moroto, July 8, 2013.

Karamoja has the lowest human development indicators in Uganda, and approximately 82 percent of the population lives on less than $1 a day, whereas the national rate is 31 percent. [35] UNDP’s Human Poverty Index (HPI) uses indicators of deprivation to determine poverty, relying on life expectancy, adult literacy, and minimum standard of living. [36] In early 2013, the national poverty index in Uganda was 27.69 percent, but for all districts in Karamoja, it ranged from 56 to 65.3 percent. [37] In children, chronic malnutrition, which results in stunted growth, was at a high of 45 percent in the region compared to 33 percent nation-wide. [38] Almost 45 percent of children in Karamoja eat only one meal per day. [39]

The region’s rough terrain and unpredictable rainfall have, in the past, resulted in severe climate variability, and in turn contributed to the region’s extreme poverty. [40] In 2006 there was serious drought; a combination of a prolonged dry spell and flooding in 2007; another drought in 2008; and 970,000 people were in need of food aid in 2009. [41] Though rainfall improved in 2010 and 2011, excessive rains have led to flooding and crop damage in areas like Kotido, Moroto, and Napak, impacting food security. [42] The UN World Food Programme (WFP) has provided food aid to Karamoja for over 40 years, and though it has significantly scaled back its operations since 2009, WFP continues to support 150,000 people in the region. [43]

Furthermore, growing environmental problems are having a greater impact on the precarious position of poor households. Climate change, deforestation, soil erosion, and desertification are all impacting harvest and production capacity of agro-pastoralists. [44]

Communities in Karamoja often face bouts of food insecurity and malnutrition, coupled with very limited access to health services. There are only five hospitals that serve all seven districts in Karamoja, [45] and a 2011 survey revealed that just 27.3 percent of the population in Kaabong district has access to health services. [46] A June 2013 food security analysis, led by the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries, revealed that up to 975,000 people in Karamoja face serious levels of food insecurity, while 234,000 more cannot meet their minimum food needs, and some districts recently experienced acute malnutrition rates. [47] In June 2013 Kaabong district reported the deaths of 41 people from starvation, according to a compilation of May and June reports by an Office of the Prime Minister-led team. [48] A July report stated the number was closer to 50 deaths across Kaabong, Napak, and Moroto districts. [49]

Entrenched poverty and environmental variability has, over the last generation, increasingly pushed people into artisanal and small-scale mining for the region’s minerals, particularly gold and marble, for survival.[50] It is not clear how many people rely on or sporadically turn to mining for cash in the dry season, but one local civil society group estimates that there are over 18,000 men, women, and children active in the sector in Karamoja.[51] Some operate in family groups, particularly in gold mining, where often men and older boys gather soil from deep, open pits while women and children sift and wash sediment and/or ferry water long distances, though these roles are flexible. Marble and limestone work involves breaking rock faces into small pieces both as an additive to cement and as bricks. These products are all sold for cash, mostly to outside middle men. Despite the back-breaking physical labor, income varies tremendously and is a gamble. Miners in Kaabong and Moroto told Human Rights Watch that occasionally they had been fortunate and been able to earn 100,000 Ugandan shillings ($40) for a day’s work mining gold. Many said they routinely make less than 2,000 Ugandan shillings ($0.75) however,[52] and complained bitterly of being cheated by middle men who purchased their gold for less than the miners felt it was worth.[53]

Local activists have noted that small scale and artisanal mining activities “are predominantly informally organized or disorganized, un-mechanized and often characterized by hazardous working conditions, lack of planning and issues related to child labour, poor health conditions and gender inequalities.”[54] Often these miners confront serious impediments if they try to formalize their work, for example, by securing a location license, due to high costs, bureaucracy, and lack of access to information. In some instances observed by Human Rights Watch, it would appear that the presence of artisanal miners is a bellwether for companies seeking to carry out mineral exploration work, raising very urgent questions about the rights of the local miners when the companies begin operations on land the locals depend on for survival.[55]

Disarmament and Abuses

Competition over scarce resources has contributed to high levels of insecurity in Karamoja. Conflicts between groups, including across international borders, take the form of cattle raids.[56] Armed criminality and cattle raiding expose the population to high levels of violence, and has restricted the movement of humanitarian workers at various times.[57]

The government has mounted several disarmament campaigns, some voluntary, some forced, in Karamoja since 2001 to collect an estimated 40,000 unlawfully-held weapons.[58] At the same time, however, government programs to improve security, including programs of disarmament, face a fundamental dilemma: guns are used to defend from raiders as well as to rob and steal. The dynamics behind weapon possession include, for some, the desperate need to secure and defend cattle and access to essential limited resources.

Since May 2006 the national army, the Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces (UPDF), tasked with some law enforcement responsibilities in Karamoja absent a fully adequate police force, renewed a forced disarmament program to curb the proliferation of small arms. In a 2007 report, Human Rights Watch documented alleged human rights violations by UPDF soldiers in “cordon and search” disarmament operations.[59] Violations included unlawful killings, torture and ill-treatment, arbitrary detention, and theft and destruction of property. Allegations of UPDF abuses continued through 2009 to 2011, though at a reduced rate.[60]

The disarmament process was slated to end in 2011, but the army continues to police Karamoja. The UN has called for a handover of law enforcement activities to local police.[61]

II. Land and Resource Rights

Indigenous Peoples Defined

The indigenous groups in Karamoja are among Uganda’s most marginalized communities.[62] There is no internationally agreed definition of “indigenous people,” but the United Nations’ Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues has relied on a description based on a multi-part analysis that includes self-identification as indigenous peoples; a historical continuity with pre-colonial and/or pre-settler societies; a strong link to the territories and surrounding natural resources; distinct social, economic, or political systems; a distinct language, culture, and beliefs; and the maintenance and reproduction of their ancestral environments and systems as distinctive peoples and communities.[63]

The African Commission’s Working Group on Indigenous Populations/Communities has affirmed this approach, stating that the “focus should be on … self-definition as indigenous and distinctly different from other groups within a state; on a special attachment to and use of their traditional land whereby their ancestral land and territory has a fundamental importance for their collective physical and cultural survival as peoples; on an experience of subjugation, marginalization, dispossession, exclusion or discrimination because these people have different cultures, ways of life or modes of production than the national hegemonic and dominant model.” [64]

This working roup, in a report from its 2006 visit to Karamoja, refers to the people of Karamoja as indigenous people and called on the government of Uganda to recognize the “pastoralists” as indigenous people “in the sense the term is understood in international law.”[65] However, the Ugandan government has not yet done so. The Ugandan constitution recognizes 56 “indigenous communities” that roughly correspond to the various ethnic groups who have historically resided within the country’s borders. These include many of the communities living in Karamoja today.[66] But the term “indigenous” corresponds to citizenship based on ethnicity, rather than to any international norm.

Domestic law does not expressly outline protections for the rights of indigenous peoples as defined by international law, nor are there any criteria in place for identification of internationally considered indigenous peoples.[67] However, the Ugandan constitution does include protections for marginalized groups and minorities that are directly relevant to international norms and would apply to indigenous peoples in Karamoja. The constitution’s National Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy affirm that the government recognizes ethnic, religious, ideological, and cultural diversity among the different peoples of Uganda,[68] and will ensure the fair representation of marginalized groups in constitutional and other bodies.[69] The constitution also guarantees non-discrimination and requires the state to take affirmative action in favor of marginalized groups, whether on the basis of “gender, age, disability or other reason created by history, tradition or custom, for the purpose of redressing imbalances which exist against them.”[70] Without expressly defining marginalized groups or minorities as “indigenous peoples,” the definitions outlined in the constitution effectively embrace the unique groups living in Karamoja and provide them protections, if such provisions are enforced.

Uganda was not present at the voting for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted by the General Assembly in September 2007. The ACHPR has expressly articulated its support for the declaration, noting that it is “in line with the position and work of the African Commission on indigenous peoples’ rights as expressed in the various reports, resolutions and legal opinion on the subject matter.”[71]

|

The African Commission’s Working Group on Indigenous Populations / Communities has debunked several misconceptions regarding indigenous peoples in Africa: Misconception 1: To protect the rights of indigenous peoples gives special rights to some ethnic groups over and above the rights of all other groups. Certain groups face discrimination because of their particular culture, mode of production, and marginalized position within the state. The protection of their rights is a legitimate call to alleviate this particular form of discrimination. It is not about special rights. Misconception 2: Indigenous is not applicable in Africa as “all Africans are indigenous.” There is no question that Africans are indigenous to Africa in the sense that they were there before the European colonialists arrived and that they were subject to subordination during colonialism. When some particular marginalized groups use the term “indigenous” to describe themselves, they use the modern analytical form (which does not merely focus on aboriginality) in an attempt to draw attention to and alleviate the particular form of discrimination they suffer from. They do not use the term in order to deny other Africans their legitimate claim to belong to Africa and identify as such. Misconception 3: Talking about indigenous rights will lead to tribalism and ethnic conflicts. Giving recognition to all groups, respecting their differences and allowing them all to flourish does not lead to conflict, it prevents conflict. What creates conflict is when certain dominant groups force a contrived “unity” that only reflects perspectives and interests of powerful groups within a given state, and which seeks to prevent weaker marginal groups from voicing their unique concerns and perspectives. Conflicts do not arise because people demand their rights but because their rights are violated. Protecting the human rights of particularly discriminated groups should not be seen as tribalism and disruption of national unity. On the contrary, it should be welcomed as an interesting and much needed opportunity in the African human rights arena to discuss ways of developing African multicultural democracies based on the respect and contribution of all ethnic groups. Source: Paraphrased from Report of the African Commission’s Working Group on Indigenous Populations/Communities, Adopted by the ACHPR at its 34th Ordinary Session, November 6-20, 2003. |

Rights to Land, Development, and Environment

Indigenous peoples have the rights to “own, use, develop, and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership or other traditional occupation or use, as well as those which they have otherwise acquired,” and to determine their own development priorities and strategies. [72] In order to realize these rights, states are required to give legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories, and resources, with due respect to the customs, traditions, and land tenure systems of the indigenous peoples concerned. [73]

Under the right to development, the Ugandan government is obligated to ensure that the peoples in Karamoja are not left out of the development process or benefits. According to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the right to development is both constitutive and instrumental, and a violation of either the procedural or substantive element constitutes a violation of the right to development.[74] The procedural element requires active, free, and meaningful participation in development choices, free of coercion, pressure, or intimidation.[75] The substantive element should include benefit sharing, improve the capabilities and choices of people, and is violated if the development in question decreases the well-being of the community.[76] The combination of these elements should result in empowerment.[77]

Uganda’s 1998 Land Act and the National Environment Act of 1995 recognize customary interests in land,[78] though the government can acquire land in order to control environmentally sensitive areas, thereby usurping customary land rights of indigenous groups.[79] The National Environment Act does highlight that environmental management should include maximum participation by the people, effectively requiring the consultation of indigenous peoples prior to the gazetting of their land.[80]Uganda’s land law recognizes customary tenure, as is the case in Karamoja, as one of four forms of land ownership.[81] To legally acquire land this way, one must seek a certificate of customary ownership, first by forming a communal land association[82] and then submitting an application at the parish.[83]

Uganda’s 2013 National Land Policy contains very progressive language regarding the rights for minorities, and more specifically for customary land owners. The policy identifies ethnic minorities as “ancestral and traditional owners,” and goes as far as to say that even though ethnic minorities are the “users and custodians of the various natural habitats,” that they are “not acknowledged even though their survival is dependent upon access to natural resources.”[84] The policy acknowledges that the establishment of national parks and development of regions, including through mining and logging, “often takes place at the expense of the rights of such ethnic minorities.”[85] It calls on the government to protect the rights to ancestral lands of ethnic minority groups and give them prompt, adequate, and fair compensation for displacement by government action.[86]

Uganda’s constitution and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Banjul Charter) guarantee every person the right to a clean and healthy environment.[87] The government is mandated to enact laws that protect and preserve the environment from degradation and to hold in trust for the people of Uganda natural assets.[88] This is realized somewhat through the National Environment Act which stipulates the nature of projects for which an environmental impact assessment (EIAs) may be required and how impact studies are to be undertaken.[89] Under the 1997Local Government Act, local governments are responsible for the protection of the environment at the district level.[90]

Free, Prior, and Informed Consent

States have a duty under international law to consult and cooperate with indigenous peoples through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent. This is supposed to occur before the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization, or exploitation of mineral, water, or other natural resources. [91] This duty is derived from indigenous peoples’ land and resource rights, discussed above. States must also provide effective mechanisms for just and fair redress for any such activities, and appropriate measures shall be taken to mitigate adverse environmental, economic, social, cultural, or spiritual impact. [92]

While these rights are most clearly enunciated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and in the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, they stem from existing international law. [93] Furthermore, African regional institutions have significantly advanced the right to free, prior, and informed consent and do not limit its application to indigenous peoples, as discussed below.

It is sometimes contended that compulsory acquisition of property or eminent domain takes precedence over free, prior, and informed consent rights. To the contrary, laws regarding compulsory acquisition must, like all other laws, respect human rights including indigenous peoples’ free, prior, and informed consent rights.[94]

The aforementioned indigenous rights are integral elements of the right to take part in cultural life, which is interdependent of the right of all peoples to self-determination and the right to an adequate standard of living, protected in both the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the Banjul Charter.[95] The UN Committee charged with interpreting the ICESCR has described how indigenous peoples’ land rights and right to free and prior informed consent stem from the right to take part in cultural life:

The strong communal dimension of indigenous peoples’ cultural life is indispensable to their existence, well-being and full development, and includes the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired.[96] Indigenous peoples’ cultural values and rights associated with their ancestral lands and their relationship with nature should be regarded with respect and protected, in order to prevent the degradation of their particular way of life, including their means of subsistence, the loss of their natural resources and, ultimately, their cultural identity.[97] States parties must therefore take measures to recognize and protect the rights of indigenous peoples to own, develop, control and use their communal lands, territories and resources, and, where they have been otherwise inhabited or used without their free and informed consent, take steps to return these lands and territories…. States parties should respect the principle of free, prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples in all matters covered by their specific rights.[98]

The UN Committee charged with interpreting the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) has similarly held that states are required to “recognize and protect the rights of indigenous peoples to own, develop, control and use their communal lands, territories and resources and, where they have been deprived of their lands and territories traditionally owned or otherwise inhabited or used without their free and informed consent, to take steps to return those lands and territories.”[99] States must ensure “that indigenous communities have equal rights in respect of effective participation in public life and that no decisions directly relating to their rights and interests are taken without their informed consent.”[100]

In May 2012, the ACHPR issued a resolution calling on states to “confirm that all necessary measures must be taken by the State to ensure participation, including the free, prior and informed consent of communities, in decision making related to natural resources governance.” [101] It also calls on states to ensure:

[R]espect for human rights in all matters of natural resources exploration, extraction, … development … and in particular … ensure independent social and human rights impact assessments that guarantee free prior informed consent; effective remedies; fair compensation; women, indigenous and customary people’s rights; environmental impact assessments; impact on community existence including livelihoods, local governance structures and culture, and ensuring public participation; protection of the individuals in the informal sector; and economic, cultural and social rights.[102]

The commission has also emphasized the importance of consultation and consent in various cases brought before it. As early as 2001 the commission emphasized the importance of “providing information on health and environmental risks and meaningful access to regulatory and decision-making bodies to communities likely to be affected by oil operations.”[103] But the commission went significantly further in a 2009 case in which it found that the Kenyan government had forcibly removed the Endorois people from their ancestral lands, violating several rights. After noting that the Endorois are an indigenous people, the commission said that in relation to “any development or investment projects that would have a major impact within the Endorois territory, the state has a duty not only to consult with the community, but also to obtain their free, prior, and informed consent, according to their customs and traditions.”[104]

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has issued a directive on Harmonization of Guiding Principles and Policies in the Mining Sector, which does not apply to Uganda but is a useful guide to an emerging standard of free, prior, and informed consent in an African sub-region. [105] In addition to emphasizing the obligations of states to respect, and ensure respect of, human rights throughout mining activities, the declaration outlines obligations for mining companies. In particular, it states that:

Companies shall obtain free, prior, and informed consent of local communities before exploration begins and prior to each subsequent phase of mining and post-mining operations.

Companies shall maintain consultations and negotiations on important decisions affecting local communities throughout the mining cycle. [106]

Uganda has not legislated to protect free, prior, and informed consent rights.

Uganda’s Mining Act

Mining activities in Uganda are controlled under the 2003 Mining Act and the 2004 Mining Regulations. The Mining Act does not currently require any form of consent or consultation with local communities prior to the application or acquisition of an exploration license.[107] While it does require a mining lease applicant to negotiate a surface rights agreement prior to the granting of a mining lease, it does not require this for an exploration license application. Ultimately, the law falls well short of protecting free, prior, and informed consent rights.[108]

The mining law specifies that regardless of land ownership, all minerals are the property of the government.[109] While any Ugandan entity can retain the right to search for and extract minerals, all prospecting, exploration, and mining can only be carried out under an appropriate license. In order to participate in mineral exploration, one must acquire a prospecting license. The license is not confined to a specific area and gives the holder a right to look for minerals and to demarcate it by planting “beacons” to indicate to others the area is exclusively booked. A prospecting license is not renewable and is valid for one year. A location license is available to locally resident artisanal miners.

When more than one entity applies for mineral rights over the same land Ugandan law requires that the first person who has marked out the land in question be accorded priority. When priority cannot be given, the commissioner of the Department of Geological Survey and Mines (DGSM) has discretion to decide who will receive priority.[110]

Companies featured in this report all eventually applied for and received exploration licenses from the DGSM or purchased the exploration licenses of others who had done the same.[111] An application for an exploration license requires basic information about the legal entity and the minerals to be explored, a map of the area, as well as payment of a fee. There is no requirement for proof of consultation with anyone from the community, however exploration entities are required to propose how they will employ and train Ugandan citizens.[112] An exploration license is usually valid for three years.

Entities intending to extract minerals for sale must apply for a mining lease. The application to the commissioner must include:

- a statement giving details of all known mineral deposits in the area, as well as possible and probable ore reserves and mining conditions;

- a technological report on mining and processing techniques to be used by the applicant;

- a statement describing the program of proposed developments and mining operations. This needs to include: the estimated capacity of production and scale of operations, the estimated overall recovery of the ore and mineral products, and the nature of the mineral products;

- a report on the goods and services which can be obtained in Uganda required for the mining operations, and proposals on the procurement of those goods and services;

- a statement on the employment and training of Ugandan citizens; and

- a business plan that forecasts capital investment, operating costs and revenues, type and source of financing, and a financial plan and capital structure. [113]

It is not until a company prepares to apply for a mining lease that Uganda’s law requires proof of communication with the land owners or occupiers. Applicants must state how many owners or lawful occupiers there are for the area he or she intends to mine, include written proof that he or she has reached an agreement with those owners or occupiers,[114] and include written proof that he or she has an agreement, negotiated with broad community support, which clearly quantifies compensation for disruption of the land.[115]

The Mining Act requires the holder of mineral rights to exercise such rights “reasonably” and in such a manner as not to adversely affect the interests of any owner or occupier of the land. However, this has not been interpreted by the courts and it is unclear what may be precisely involved in complying with this provision. The act states that the land owner or lawful occupier is entitled to demand either compensation for disturbance or a share of royalties.[116] The act also stipulates circumstances under which compensation may be paid to owners or persons lawfully occupying land that is the subject of a mineral right, for example for any crops, trees, buildings, etc., that may be damaged in operations. However, the law specifically states that compensation will only be paid “on demand” of the land owner and must be requested within one year of the damage.[117] Given the very limited knowledge of land owners as to their rights under the mining law, it is likely that rightful compensation payments are neglected.

Every holder of a mining lease is to carry out an environmental impact assessment of the proposed operations in accordance with the provisions of the National Environment Act and to take all necessary steps to ensure the prevention and minimization of pollution of the environment. It also requires environmental management and restoration plans.[118]

The Mining Act also stipulates how royalties must be allocated to the various stakeholders—80 percent to the central government, 10 percent to the district government, 7 percent to the sub-county, and 3 percent to the “owners or lawful occupiers of land subject to mineral rights.”[119] Payments to the community can be quite difficult when there is no bank account or legal entity recognized to receive the money.[120] Some people suggested that payment could be made to the sub-county administration for the benefit of the entire community.[121]

Ugandan laws do not require any social or human rights impact assessments (HRIAs), though this is an important aspect of ensuring protection and should be remedied. Such assessments should be required before any exploration work is scheduled to begin and involve meaningful and sustained engagement with the communities. Most likely, HRIAs could be accomplished by amending the Mining Act and then drafting accompanying regulations. For example, the Uganda Human Rights Commission could lead a consultative process to draft guidelines and regulations for such assessments, maintain a list of qualified independent experts from which companies could select, and then be in charge of evaluating HRIAs as and when they are submitted, as the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) does now for environmental impact assessments.

III. Three Mining Companies’ Practices in Karamoja

East African Mining: Kaabong District

East African Mining Ltd. (EAM), a local subsidiary of East African Gold, incorporated in Jersey, holds exploration licenses covering several hundred square miles of Kaabong district.[122] Since June 2012, the junior mining company has been using various prospecting methods to sample soil for gold in the parishes of Lois, Lopedo, Loyoro, Naikoret, and Sokodu, which span four sub-counties in Kaabong.[123]

Research undertaken by Human Rights Watch indicates that EAM did not receive, or even seek, the permission or consent of the indigenous land owners prior to undertaking exploration on their land.[124] Human Rights Watch interviewed 38 community members in the Kaabong parishes where EAM had been exploring. All of those interviewed said that they were not consulted by EAM about their planned activities prior to seeing them in their community, extracting soil samples. EAM Chief Executive Officer Dr. Tom Sawyer acknowledged that the company’s consultations had initially been limited, and even non-existent prior to commencing exploration; however, the company worked to improve them over time.[125] Several people said that they were scared by the sight of unknown men accompanied by soldiers. Human Rights Watch found that there was mass confusion in these communities regarding what EAM was doing, the likely impact on their communities, and the potential benefits of agreeing to allow EAM to proceed with exploration.

One woman in Lois described her first experience with EAM:

I was surprised to hear some noise one day…. Then we saw some soldiers. They stopped and we saw some men had a machine. They took some soil, using the machine, and put it in polythene bags. I almost took off running with fear.[126]

EAM had two or three soldiers accompany field teams, in addition to having soldiers guard their camp.[127]

In the early months of EAM’s activities employees took soil samples from peoples’ houses, in addition to their gardens and grazing lands.[128] Sawyer told Human Rights Watch that when he heard of this, he advised his staff to no longer do so.[129]

Community members, local government officials, and former employees described EAM’s exploration process damaging gardens.[130] When gardens were damaged by excavators or due to trenching, land owners received some compensation.[131] However, when sampling uprooted just a few crops, there was no compensation.[132]

Another Lois community member described his experience:

Eight men in yellow uniforms just entered my garden and started excavating. They said nothing. They just started digging and taking my soil. I just looked at them. I was afraid, so, I couldn’t get near them. They stepped on some of our crops and damaged them. I asked them, “Why are you destroying our crops”. They said, “It will be good for your survival. We are looking for something. It will benefit you….” We were afraid and feared to stop them. They moved around like a rooster, like this was their land.[133]

An employee of EAM said, to the contrary, “We could traverse their garden. They are our people. No one asked us for compensation, but we tried our best [not to damage their gardens].”[134] The local EAM manager said that he would provide compensation, but did not trust what people would do with it:

I would go to the district office ... to work out compensation. I prefer to give [people] food so I would convince them to let me bring them food. If I give them money they just spend it on drink. They’re shit. They don’t even feed their children.[135]

According to both EAM employees and community members, on several occasions community members chased the company employees off their land.[136] Despite this, when Human Rights Watch asked the field manager about the community’s response to EAM’s activities, he said “The community welcomed it so much. It helped areas.”[137] When asked about the complaints that the company had received, he said, “The first times we received complaints, it was through politicians. Politicians are big shits. I took a lot of time to convince them… There were too many [meetings with community members].”[138]