Summary

Ly Sim passed productivity tests and was promoted t0 team leader in the sewing division of her factory in Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital, in 2012.[1] A few months later, Sim, in her late 20s, became visibly pregnant. Factory management demoted her and cut her pay. When she and other workers protested with the help of the factory union, they were summarily fired.

Devoum Chivon helped form a union in the factory where he worked and was elected president in late 2013. Within days of being notified about the new union leaders, the factory managers pressured Chivon to quit the union and offered him a bribe, which he refused. The management then criticized the newly elected union leaders’ job performance and fired them.

Leouk Thary, in her 20s, worked in a garment factory on four-month short-term contracts that her managers repeatedly renewed. One day in November 2013 she had a bad nosebleed and sought exemption from overtime work. Even though her managers told her to continue working, she went to see a doctor. She returned the next day with a medical certificate requesting sick leave for nose surgery. She was fired immediately.

Workers in Cambodia’s garment factories—frequently producing name-brand clothing sold mainly in the United States, the European Union, and Canada—often experience discriminatory and exploitative labor conditions. The combination of short-term contracts that make it easier to fire and control workers, poor government labor inspection and enforcement, and aggressive tactics against independent unions make it difficult for workers, the vast majority of whom are young women, to assert their rights.

Recent events linked to labor rights in Cambodia have attracted international attention. There have been repeated episodes of workers fainting on the job. In January 2014, police, gendarmes, and army troops brutally crushed industry-wide protests for a higher minimum wage. And the authorities have introduced more burdensome union registration procedures.

Lack of accountability for poor working conditions in garment factories is at the center of troubled industrial relations in Cambodia. This report—based on interviews with more than 340 people, including 270 garment workers from 73 factories in Phnom Penh and nearby provinces, union leaders, government representatives, labor rights advocates, the Garment Manufacturers Association of Cambodia, and international apparel brand representatives—documents those working conditions, identifies key labor rights concerns voiced by workers and labor rights advocates, and details the failure of Cambodia’s labor inspectorate to enforce compliance with applicable labor laws and regulations.

The report also examines the role of the Better Factories Cambodia, an International Labour Organization factory monitoring program launched in 2001.

The Cambodian government is primarily responsible for ensuring compliance with international human rights law, including labor rights. However, international clothing and footwear brands have a responsibility to promote respect for workers’ rights throughout their supply chains, including both direct suppliers and subcontractor factories. As documented in this report, many brands have not fully lived up to these responsibilities due to poor supply chain transparency, the absence of whistleblower protections, and failure to help factories correct problems in situations where that is both possible and warranted. Some brands remain nontransparent about their policies and practices, withholding information on issues of concern, while other brands notably provide information and voluntarily subject themselves to greater public scrutiny and demonstrate a commitment to improved policies.

***

Garment and textile exports are crucial for the Cambodian economy. In 2013, Cambodian global exports amounted to roughly US$6.48 billion, of which garment and textile exports accounted for $4.96 billion; export of shoes accounted for another $0.35 billion. In 2014, garment exports reportedly totaled $5.7 billion. The industry is a major source of non-agrarian employment, particularly for women. Women dominate Cambodia’s garment sector, making up an estimated 90 to 92 percent of the industry’s estimated 700,000 workers. These numbers do not include the many women engaged in seasonal home-based garment work.

Cambodia enacted a strong labor law in 1997. But its enforcement remains abysmal, in large part due to an ineffective government labor inspectorate. Better Factories Cambodia (BFC), a third-party monitor that focuses primarily on factories with an export license, helps fill the monitoring gap in export-oriented factories and a few subcontractor factories but cannot be a substitute for a strong labor inspectorate. Some of the worst working conditions in Cambodia, however, are in smaller factories that lack such licenses and work as subcontractors for larger export-oriented factories. Because BFC’s mandatory monitoring is limited to export-oriented factories, its monitoring services extend to such subcontractors only where brands and factories identify them and pay for BFC services.

Hiring practices also influence labor law compliance. In many factories, managers repeatedly use short-term contracts beyond the legally permissible two years as a way of controlling workers, discouraging union formation or participation, or avoiding paying benefits. This practice has become a key point of contention, fueling tense industrial relations.

Some factories, especially those working on a subcontracting basis for larger factories, also employ workers on a casual daily or hourly basis. These workers face additional barriers to unionizing and filing complaints about working conditions. Some factories also outsource work seasonally to home-based workers, whose work remains poorly regulated and invisible in monitoring processes.

Even though long-term Cambodian workers, as well as limited-term workers employed full-time for 2 consecutive periods of 21 days or more, are entitled to most of the same basic workplace benefits under the law, casual workers and those on short-term contracts risk relatively easy retaliation by management through dismissal or contract non-renewal. They are more likely to be denied benefits or face other discrimination, but have less access to reporting mechanisms and union support.

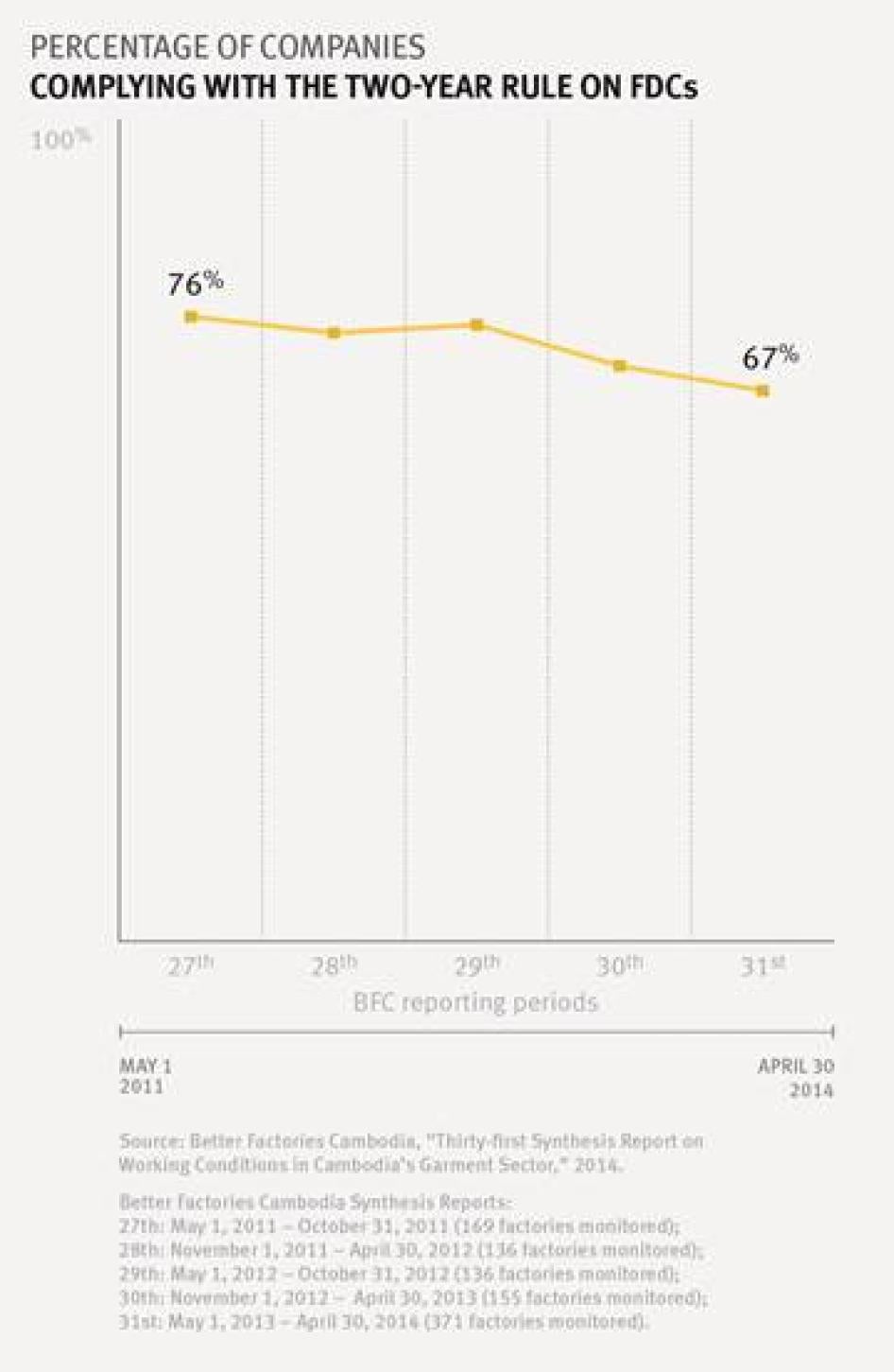

Contrary to claims by the Garment Manufacturers Association of Cambodia (GMAC) that factories using repeated short-term contracts are “black sheep,” BFC reported that the number of surveyed factories complying with the two-year rule on short-term contracts (called fixed-duration contracts or FDCs in Cambodia) dropped from 76 percent in 2011 to 67 percent in 2013-2014. Since 2011, BFC has consistently found that nearly a third of all factories used FDCs to avoid paying maternity and seniority benefits.

Labor Rights Abuses

Human Rights Watch documented labor rights abuses in both export-oriented factories and subcontractor factories in Cambodia. These include forced overtime and retaliation against those who sought exemption from overtime, lack of rest breaks, denial of sick leave, use of underage child labor, and the use of union-busting strategies to thwart independent unions. In addition, women workers faced pregnancy-based discrimination, sexual harassment, and denial of maternity benefits.

Forced Overtime

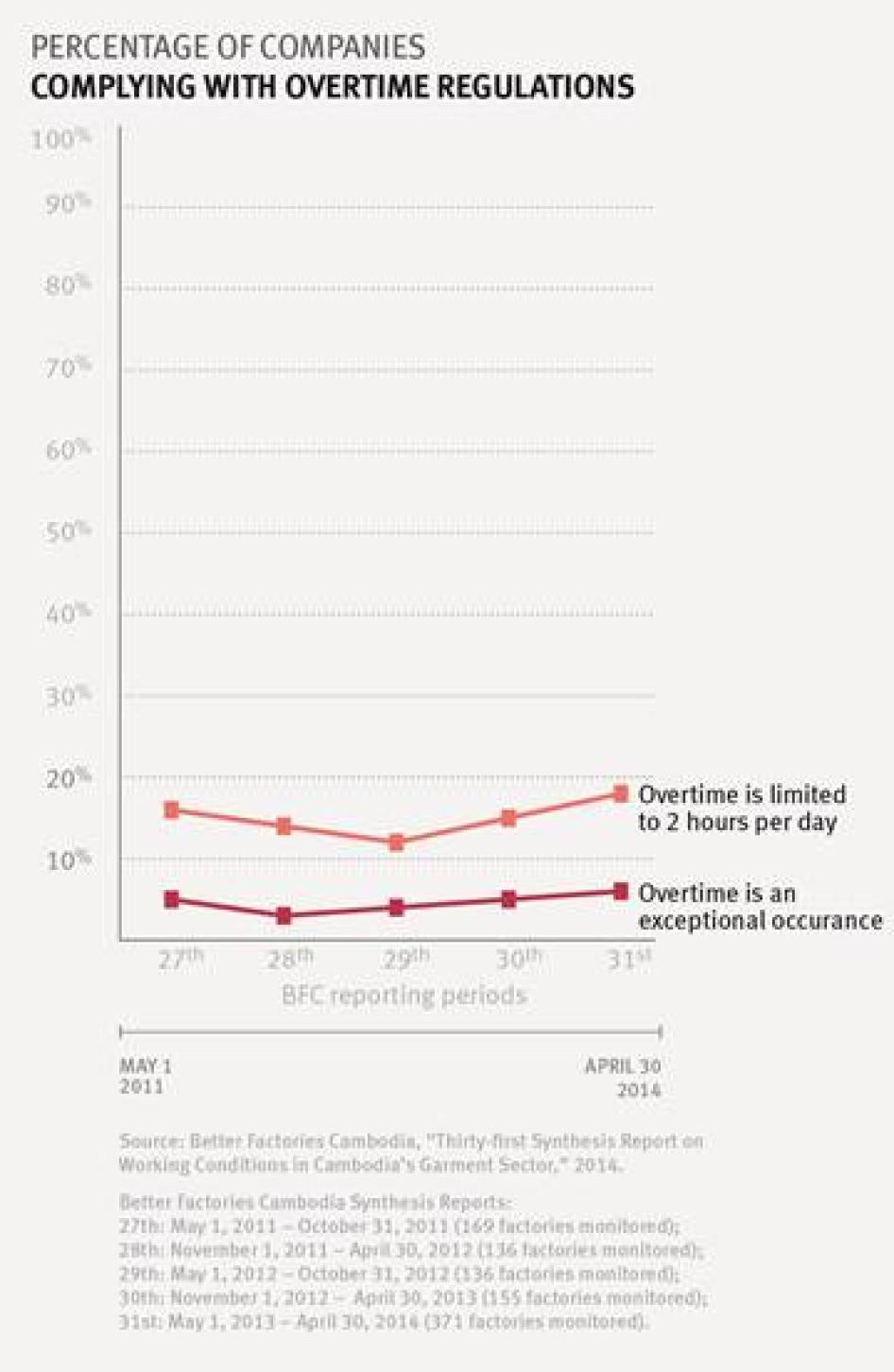

Human Rights Watch discussed concerns regarding overtime work with workers in 48 factories. Cambodia’s Labor Law limits weekly (beyond 48 hours) overtime work to 12 hours (2 hours per day). Workers generally preferred some overtime work to supplement their incomes, but complained that factory managers threatened them with contract non-renewal or dismissal if they sought exemption from doing overtime work demanded of them. Most of the workers we interviewed performed overtime work far exceeding the 12-hour weekly limit.

In at least 14 of the 48 factories, Human Rights Watch documented recent examples of management retaliation against workers who did not want to do overtime work, including dismissal, wage deductions, and punitive transfers of workers from a monthly minimum wage to a piece-rate wage where income depends on the number of garments individuals produced. For example, in November 2013, a factory dismissed 40 workers for refusing to do overtime until 9 p.m. It subsequently reinstated half the workers, however, after protests and negotiation with an independent union.

Factories usually assign garment workers daily production targets. Many workers—from both large factories directly supplying to international brands and small, subcontractor factories—complained that management pressure to meet production targets undermined their ability to take breaks to use washrooms, rest, or drink water. Some workers also recounted how factory managers promised small cash incentives in the range of 500 to 3000 riels ($0.12 to $0.75) a day to meet production targets, but at times did not pay these promised incentives. In other cases, workers said they made upward revisions to targets to compensate for increases in statutory minimum wages. Many workers reported being subject to invectives, and a few said they were physically intimidated if perceived as being “slow.”

Key Concerns for Women Workers

Pregnancy-related discrimination and sexual harassment at the workplace were two key concerns for women workers in Cambodia.

Discrimination against pregnant workers took different forms at different stages of the employment process, including during hiring, promotion, and dismissal, and included failure to make reasonable workplace accommodations to address the needs of pregnant workers. Human Rights Watch documented one or more of these problems in at least 30 factories. Cambodia’s Constitution and the Labor Law forbid dismissals based on pregnancy. The Labor Law also guarantees all pregnant workers three months’ maternity leave irrespective of the duration of service and maternity pay for workers with a year’s uninterrupted service.

Workers said that factory managers refused to hire visibly pregnant workers, echoing findings from a 2012 International Labour Organization (ILO) report on gender equality in garment factories. Pregnant women on short-term contracts were unlikely to have their contracts renewed, allowing their managers to avoid providing maternity benefits.

Factory managers also often failed to make reasonable accommodations for pregnant workers such as more frequent bathroom breaks or lighter work without loss of pay. Many found it difficult to work long hours, including overtime, without adequate breaks to rest or use washrooms. Many interviewees said workers often resigned from factories as their pregnancy progressed because managers harassed them for being “slow” and “unproductive.”

Contrary to a ruling by the Arbitration Council, a dispute resolution forum, workers from some factories found it difficult to take medically approved sick leave and were denied their entire month’s $10 attendance bonus for missing a few hours or single day of work. The attendance bonus is an important part of workers’ remuneration and workers who do not attend work, as attested by medical professionals, are entitled to a pro-rated share of the bonus. This especially had an impact on pregnant workers who felt unable to take sick leave.

Another issue affecting women is sexual harassment at the workplace. Workers, independent union representatives, and labor rights activists said that sexual harassment in garment factories is common. The 2012 ILO report found that one in five women surveyed reported that sexual harassment led to a threatening work environment.

The forms of sexual harassment that women recounted include sexual comments and advances, inappropriate touching, pinching, and bodily contact. Workers complained about both managers and male co-workers.

Cambodia’s Labor Law prohibits sexual harassment but does not define it. Nor does it define sexual harassment at the workplace, outline complaints procedures, or create channels for workers to secure a safe working environment.

I sit for 11 hours and feel like my buttocks are on fire. We can’t go to the toilet. —Keu Sreyleak (pseudonym), garment worker, group interview, factory 60, Phnom Penh, December 7, 2013 It doesn’t matter whether you are pregnant or not—whether you are sick or not—you have to sit and work. If you take a break, the work piles up on the machine and the supervisor will come and shout. And if [a pregnant] worker is seen as working “slowly” then her contract will not be renewed. —Human Rights Watch interview with Po Pov (pseudonym), worker, factory 3, Phnom Penh, November 22, 2013 A worker in my team wanted to leave early. We have to do overtime work till 9 p.m. every day. She had her period and had severe cramps and so requested that she will do overtime work only till 6 p.m. They shouted at her and said they would reduce $7 from her wages and not renew her contract. So she didn’t leave and continued to work. —Human Rights Watch interview with Kong Chantha (pseudonym), worker, factory 9, Phnom Penh, November 30, 2013 There is one male worker who harasses me a lot. Each day it’s something different. One day he says “Oh your breasts look larger than usual today.” On another day, he says, “You look beautiful in this dress—you should wear this more often so I can watch you.” There are others who purposely brush past us or pinch our buttocks while walking. Sometimes I feel like complaining. I don’t like it at all. But who do I complain to? —Human Rights Watch interview with Keu Sophorn (pseudonym), worker, factory 18, Phnom Penh, December 5, 2013 If we have taken three days [sick] leave, then they deduct $20 from what we have earned. They say to us: “If you want to earn that money back, work more.” We only bring medical certificates because we feel they will scream at us less. —Human Rights Watch interview with Chhau San (pseudonym), worker, factory 15, Kandal province, November 24, 2013 |

Anti-Union Discrimination

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch found evidence of union-busting activity in at least 35 factories in Cambodia since 2012. Relevant practices included keeping long-term workers on short-term contracts to discourage their participation in union activities, shortening the length of male workers’ contracts, dismissing or harassing newly elected union representatives to prevent formation of independent unions, and encouraging pro-management unions.

All of the independent unions interviewed for this report—Coalition of Cambodian Apparel Workers Democratic Union (CCAWDU), National Independent Federation of Textile Unions in Cambodia (NIFTUC), Collective Union of Movement of Workers (CUMW), and Cambodian Alliance of Trade Unions (CATU)—said as soon as workers initiated union-formation procedures, factory management would dismiss union office-bearers or coerce or bribe them to resign, thwarting union formation.

|

Workers formed a union affiliated to CCAWDU and notified factory management in late 2013. Soon after being notified, the management called the elected representatives and presented them with the option of giving up their union positions for promotions and a hike in wages. When the president and vice president refused to accept the offer, they were dismissed. CCAWDU supported the two workers in bringing a claim before the Arbitration Council, a dispute resolution body, which ruled in favor of the workers in December 2013. At this writing the factory had yet to comply with the ruling. |

Cambodian officials with the Ministry of Labor and Vocational Training (the “Labor Ministry”) have also introduced bureaucratic obstacles to union formation. They have delayed licensing unions for months since December 2013. They also now require union leaders to produce a certificate from the Ministry of Justice stating the worker in question has not been convicted of any criminal offense. Independent union leaders told Human Rights Watch that these changes would prolong the union registration process, giving factory management more time to take retaliatory measures against workers temporarily leading the union.

Leaders from independent union federations alleged that Labor Ministry officials acted arbitrarily against independent unions, rejecting their applications citing inconsequential typographical errors. Such practices violate Cambodia’s international obligations to respect and protect workers’ freedom of association and right to organize.

In 2014, the Labor Ministry also revived an earlier draft trade union law, citing a multiplicity of unions and “fake unions” as problems that the government needed to address. The draft law curbs workers’ freedom to form a union by introducing a high threshold for the minimum number of workers needed to support union formation and gives overarching powers to the Labor Ministry to suspend union registration without any judicial review.

Subcontracting and the Role of Brands

The labor rights concerns, discriminatory practices against women, and union-busting actions described above were particularly pronounced in subcontractor factories. Many factories directly supplying to international brands subcontract to other, often smaller, factories that are subjected to little or no monitoring and scrutiny. At least 14 of the 25 subcontracting factories Human Rights Watch examined appeared not to be monitored by BFC— despite operating and producing for international brands for several years most of the factories did not appear on BFC’s January 2015 factory monitoring list.

The working conditions in the subcontractor factories we investigated were usually worse than those in larger factories. The former were more likely to use casual hiring arrangements and issue repeated short-term contracts. Because many of these factories are small and physically unmarked—and often not monitored in any way—independent union leaders said it was more difficult to unionize for fear that factories would briefly suspend operations, laying off all the workers in the process. Women in these factories often said they were denied benefits including maternity leave and maternity pay.

Very few international clothing brands disclose the names and locations of their production units—suppliers and subcontractors—even though disclosures can help workers and labor advocates to alert brands to labor rights violations in factories producing for them. Such disclosure is neither impossible nor prohibitively expensive and there appears to be no valid reason for brands to withhold this information. For example, Adidas wrote to Human Rights Watch that it first started privately disclosing its supplier list to academics and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in 2001 and moved to a public disclosure system in 2007. In 2014, Adidas moved to a biannual disclosure. H&M started publicly disclosing its supplier list in 2013 and updates it annually.

Other brands operating in Cambodia, including Gap, Marks and Spencer, and Joe Fresh, have not disclosed their suppliers publicly. Marks and Spencer wrote to Human Rights Watch stating that the brand will make its global suppliers list public by 2016. In October 2014, a Gap representative told Human Rights Watch that the brand is examining the implication of such disclosure for its business. Loblaw (owner of Joe Fresh) and Armani do not disclose their global supplier list and did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s inquiries on the subject.

Some suppliers may farm out their work to subcontractors without brand authorization. Dealing with unauthorized subcontracting is complex. But international apparel brands can do much more to help fix labor rights abuses in unauthorized production units brought to their attention.

While brands depend on workers and independent unions to alert them to unauthorized subcontractors in their supply chain, none of the brands except Adidas provided Human Rights Watch with evidence of a process for whistleblower protection to mitigate possible management retaliation against workers who raise concerns. In October 2014, Adidas introduced a written anti-retaliation clause in its grievance reporting system whereby workers can report retaliation, seek investigation, and obtain redress.

There is a need for much more effective whistleblower protection for workers in factories. For example, workers told Human Rights Watch that after they provided information on subcontractors to external monitors in mid-2012, factory managers filed false complaints of theft against one worker and compelled others to testify against the worker, threatening dismissal if they did not obey. Several workers were dismissed.

Brands also sometimes issue stop-production orders as soon as unauthorized subcontracts are brought to their attention, even in situations where prompt remediation in the subcontractor factory is feasible. This hurts worker incomes in the affected subcontracting factories, creating a disincentive for workers to report abusive conditions.

As set out in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, businesses have a responsibility to minimize human rights violations in their supply chains irrespective of whether they directly contributed to the violation, and to adequately address any abuses that do take place. In order to encourage workers to report abusive conditions and to avoid negative impacts on workers’ jobs and wages, Human Rights Watch recommends that, where feasible and appropriate, international brands give suppliers in Cambodia adequate opportunities to remedy problems before terminating their business relationships.

H&M Case Study

Factory 1, a direct supplier to H&M, subcontracts work to many smaller factories. Team leaders in factory 1 allegedly told workers that they should work Sundays, their day off, at an unauthorized subcontractor to help meet production targets and supplement their incomes because factory 1 was not going to provide them with any opportunities for overtime work. In their Sunday and public holiday work at the unauthorized subcontractor, they worked on H&M garments but without overtime pay. By outsourcing the work to a subcontractor, factory 1 was able to bypass labor law provisions governing overtime wages and a compensatory day off for night shifts or Sunday work.

Human Rights Watch also spoke to five workers from a subcontractor factory supplying factory 1. Workers knew their factory was “sharing business” and was producing for H&M because the managers had discussed the brand name and designs with them. When they had rush orders, the workers report that they were not permitted to refuse excessive overtime, including on Sundays and public holidays, and were not paid overtime wage rates.

The workers in the subcontractor factory considered organizing a union but were afraid of retaliation if they did so. They also reported that the factory employed some children below the legally permissible age of 15, and that those children were made to work as hard as the adults.

Marks and Spencer Case Study

Factory 5 is a small subcontractor factory that was producing for Marks and Spencer and received regular orders from one or two direct suppliers at least until November 2013, when we spoke to workers there.

Workers told Human Rights Watch that they received three-month fixed term contracts, which were extended beyond two years. Factory managers allegedly dismissed workers who raised concerns about working conditions or chose not to renew their contracts. Issues raised by workers that we interviewed included discrimination against pregnant workers, lack of sick leave, forced overtime, and threats against unionizing.

Joe Fresh Case Study

In 2013, factory 4 produced for Marks and Spencer, Joe Fresh, and other international brands and periodically subcontracted work to other factories.

Workers from two subcontractor factories that produced for factory 4 told Human Rights Watch that they were hired on three-month short-term contracts repeatedly renewed beyond two years. Workers reported a number of labor law violations, including wages lower than the then-statutory minimum of $80, forced overtime without overtime pay rates, absence of maternity pay for eligible workers, and disproportionate deductions of their monthly attendance bonus for a single day of sick leave. The factories did not have a legally mandated infirmary even though there were more than 50 workers in each factory. Workers said that the subcontractor factories also employed children and hid them when there were visitors.

Gap Case Study

Factory 60 is a small subcontractor factory that periodically produced for Gap until at least December 2013, when Human Rights Watch spoke to workers there.

Most of the factory workers we spoke with had worked there for more than two years and were repeatedly issued short-term contracts. They did not receive benefits accorded to long-term workers. They said the managers of the factory had taken a hostile approach to unions and workers were scared of forming a union or openly organizing within factory premises.

The factory allegedly discriminated against pregnant workers in hiring. Workers reported that women who gave birth did not receive maternity pay even when they had worked at the factory for more than a year. The workers described seeing a fellow worker dismissed for refusing overtime work. Even though the factory employed more than 300 workers, there was no infirmary or nurse in the factory.

A Failure of Government Accountability

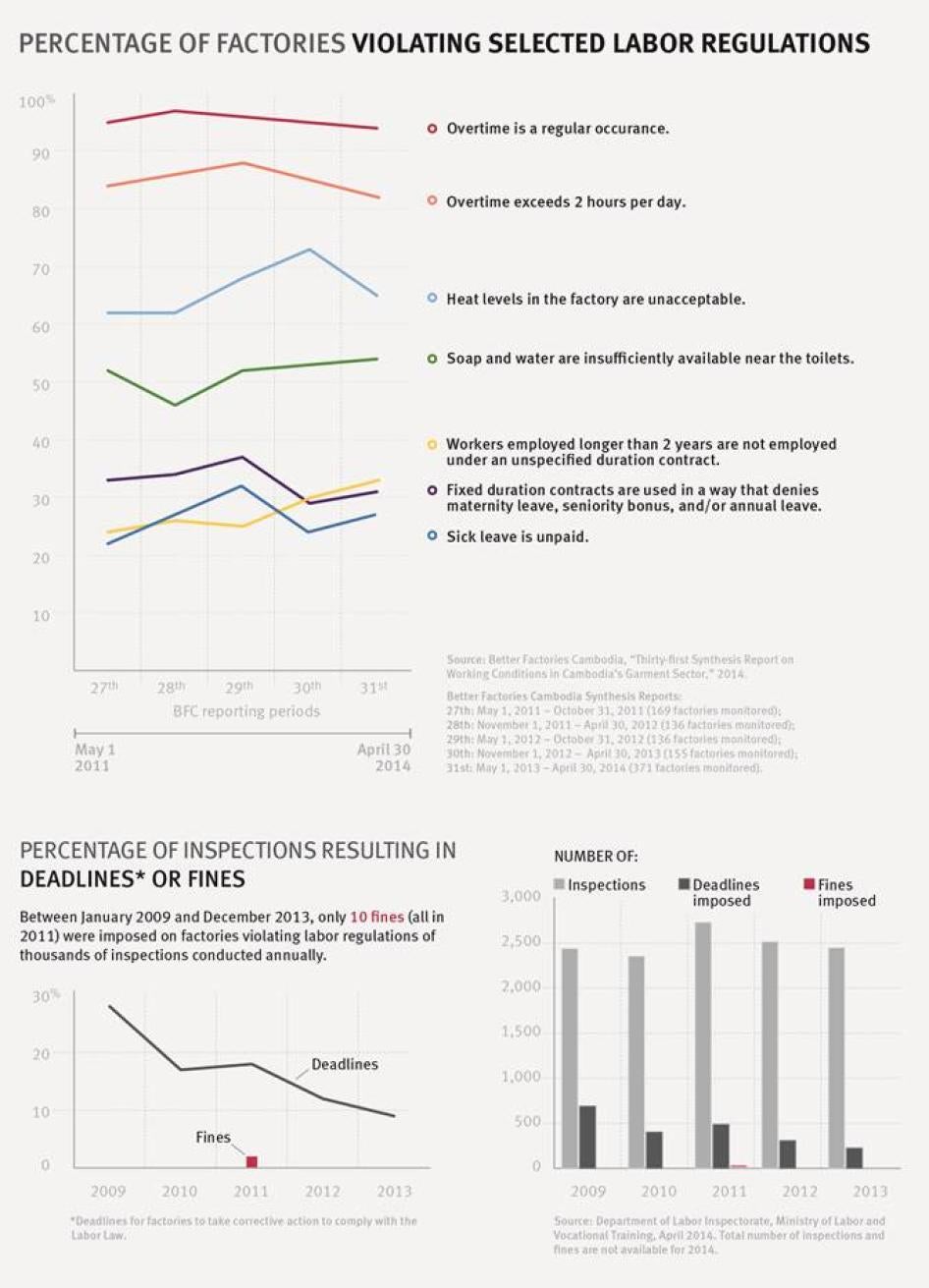

The Cambodian government has obligations under international law to ensure that the rights of workers are respected, and that when abuses occur, they have access to redress. Irrespective of whether a factory is a direct supplier or a subcontractor to an international purchaser, its working conditions should be monitored by the government’s labor inspectorate, which is tasked with enforcing the Labor Law and has powers to initiate enforcement action. But to date, Cambodia’s labor inspectorate has been wholly ineffectual, and the subject of numerous corruption allegations.

In 2014, the Labor Ministry created integrated labor inspectorate teams to streamline factory inspections. It committed itself to providing the teams with better training (in cooperation with the ILO) to investigate and report factory working conditions accurately. While these are welcome preliminary steps, it is clear that many additional measures are needed to improve government rigor in monitoring factory working conditions.

Corruption is a key issue that affects the credibility of the labor inspectorate. Two former labor inspectors independently told Human Rights Watch about an “envelope system” where factory managers thrust an envelope with money to visiting inspectors in exchange for favorable reports.

The Labor Ministry’s own data shows its enforcement track record is poor. For example, official data provided to Human Rights Watch shows that between 2009 and December 2013, labor authorities imposed fines on only 10 factories and initiated legal proceedings against 7 factories. Yet, in 2013 the ministry had found that at least 295 factories (not all garment factories) had violated the Labor Law. In December 2014, Labor Ministry officials told Human Rights Watch they had fined 25 factories in the first eleven months of 2014. In February 2015, Khmer-language media reported that in 2014 the labor inspectorate had taken action against 50 factories without specifying details. Furthermore, even though ministry officials insisted that their investigators found labor rights violations in the 10 low-compliance factories named in Better Factory Cambodia’s Transparency Database, they could not provide any information about resulting enforcement action in accordance with a 2005 circular issued by the Cambodian government, which empowers the Ministry of Commerce to cancel export licenses.

Enhancing Better Factories Cambodia

Particularly given the weakness of the labor inspectorate, BFC fills a critical monitoring role in Cambodia’s garment industry. Its factory-level, third party monitoring reports can be purchased and used by international apparel brands for their audits. These reports are behind a pay-wall for all others except the factory itself. Following criticism about the lack of public disclosure of its findings, BFC launched a Transparency Database in March 2014 despite significant resistance from the Cambodian government and the manufacturers represented by GMAC.

While BFC’s reports enjoy widespread credibility internationally, many Cambodian workers we spoke with expressed a lack of confidence in BFC monitoring and said managers coached or threatened workers ahead of external visits. Workers recounted how factory managers made announcements using the public announcement system, sent messages through team leaders, or called workers and warned them not to complain about their working conditions to visitors. In one case, a worker said that factory managers offered to pay money to workers who gave positive reports.

In addition to being coached, workers were told to prepare for “visitors.” They were told to remove piles of clothes from their sewing machines and hide them and were given gloves and masks just before visitors arrived. Lights and fans that were normally switched off were turned on, drinking water supplies were refilled, and underage child workers were hidden.

Before ILO comes to check, the factory arranges everything. They reduce the quota for us so there are fewer pieces on our desks. ILO came in the afternoon and we all found out in the morning they were coming. They told us to take all the materials and hide it in the stock room. We are told not to tell them the factory makes us do overtime work for so long. They also tell us that if [we] say anything we will lose business. —Human Rights Watch group interview with Nov Vanny (pseudonym) and Keu Sophorn (pseudonym), workers, factory 18, Phnom Penh, December 5, 2013 Our factory started using the lights this year. As soon as the security guard finds out there are visitors and tells the factory managers, the long light near the roof will come on…. And the group leaders will start telling all the workers to clean our desks; we have to wear our masks, put on our ID cards, and cannot talk to visitors. Everyone knows this is a signal. —Human Rights Watch interview with Leng Chhaya (pseudonym), worker, factory 32, Phnom Penh, November 29, 2013 |

BFC takes a number of measures aimed at counteracting management coaching. BFC’s factory monitoring methods include unannounced visits, a 30-minute outer limit on the time monitors can be made to wait outside the factory when they arrive unannounced, monitors’ discretion to convene a fresh group of workers if the first group appears to be coached, and interviews with some workers off-site. Workers told Human Rights Watch, however, that they still need a direct mechanism to report labor rights violations to BFC.

A significant deficiency is that BFC’s factory reports are not available to workers individually or even to unions, making it practically impossible for workers to verify whether the BFC reports accurately portray actual working conditions in any given factory.

The garment industry plays a critical role in Cambodia’s economy, including by employing a large number of women. The detailed recommendations below to the Cambodian government, garment factories, international brands, BFC, unions, and international donors aim to improve labor practices so that Cambodia can be a model for good working conditions for garment workers.

Recommendations

The primary responsibility to improve labor conditions in the Cambodian garment industry rests with the Cambodian government. But a number of other influential actors—brands, Better Factories Cambodia (BFC), the Garment Manufacturers Association of Cambodia (GMAC), and unions—play an important role in ensuring that working conditions in factories adhere to the Labor Law and international standards. While paying attention to individual labor rights concerns, the structural issues that underlie a range of labor rights problems—hiring practices, union-busting strategies, and unauthorized subcontracting—need urgent attention. The vast majority of workers are women and the issues affecting women workers are of particular concern.

To the Ministry of Labor and Vocational Training

On hiring practices

-

Improve

the regulation and monitoring of hiring practices:

- Issue a proclamation (prakas) requiring factories that employ a significant number of workers on short-term contracts (called fixed-duration contracts or FDCs in Cambodia) to furnish information on the number of workers employed each month for the preceding year to demonstrate that business-related fluctuations are driving the heavy use of FDCs.

- Issue a proclamation clarifying home-based garment workers have the same rights as other workers and mandating that subcontractors issue them proof of work.

- Issue a proclamation requiring factories to provide all workers identity cards listing their actual start date and regularly update them.

On unions

- Review, in consultation with independent unions and the ILO, all union registration procedures and eliminate unnecessarily burdensome requirements (such as certificates of no criminal conviction) that violate ILO Convention No. 87 on Freedom of Association. In the interim, accept and promptly grant pending applications for union licenses.

- Eliminate the requirement that unions inform employers of the identity of newly elected office-bearers as a prerequisite to union registration. Consult with ILO and labor rights experts and develop an alternative notification system to ensure legal protection for unions. For example, notification could be permitted to a neutral third party such as the ILO.

- Develop, in consultation with independent unions and Better Factories Cambodia, a transparent system of union registrations, in which the status of each application can be tracked online.

- Ensure that any trade union law adopted in Cambodia fully respects international standards, and ensure that the drafting process is transparent and includes consultation with independent labor unions and labor rights advocates.

On labor inspections

-

Improve

labor inspection methods, including through periodic joint monitoring with BFC,

and paying special attention to:

- the repeated use of fixed-term contracts;

- forced overtime and retaliatory measures for refusing overtime;

- complaints about working conditions for pregnant workers, including discrimination in hiring, contract renewals, promotions, and provision of reasonable workplace accommodation;

- denial of sick leave and disproportionate deduction of attendance bonuses; child labor; and

- complaints of discrimination against union leaders from licensed unions and newly formed unions.

- Publicly and regularly disclose (such as every four months) the number of factories inspected, key labor rights violations found, and enforcement actions taken. The terms of disclosure should be finalized in consultation with various actors, including labor rights advocates, independent unions, and BFC.

- Ensure adequate resources for labor inspectors in Phnom Penh and other provinces and periodically disclose a statement of allocation and expenditure, including out-of-pocket reimbursement for factory inspectors, in order to curb rent-seeking.

On gender-related concerns

-

Issue

a proclamation or other appropriate ministerial regulation, developed in

consultation with various actors including the Ministry of Women’s

Affairs, independent unions, and labor rights advocates, that:

- Establishes a definition of sexual harassment at the workplace, outlines prevention measures that employers should take, and sets forth independent grievance redress procedures that employers should create to investigate and respond to individual complaints of harassment.

- Establishes protections against unfair dismissal of workers in accordance with ILO Convention No. 158 on the Termination of Employment at the Initiative of the Employer, 1982.

- Develops reasonable accommodation measures for pregnant workers in accordance with the ILO Convention and Recommendation on Maternity Protection, 2000. >

On child labor

- Work with the Ministry of Education, ILO, GMAC, nongovernmental organizations, and others to promote education and sustainable solutions to underlying causes of child labor, including through programs to support employment, skills development, and job training opportunities for young workers.

To the Ministry of Commerce

- Publicly and regularly disclose (such as every six months) the names and number of garment and footwear factories that are registered with the ministry so that these may be cross-verified by labor rights groups and the Labor Ministry for inspections.

- Publicly and regularly disclose (such as every four months) any actions initiated by the ministry against garment and footwear factories that are not compliant with Cambodia’s Labor Law, especially factories appearing on BFC’s Transparency Database.

- Publicly and regularly disclose (such as every six months) the names of all international apparel and footwear brands sourcing from Cambodia.

To the Royal Government of Cambodia

- Monitor and issue public progress reports on enforcement actions initiated by the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Labor and Vocational Training against low-compliance factories named in the BFC Transparency Database.

- Expand the mandate of BFC to include factories without export permits.

- Enact a freedom of information law that meets international standards; consult with local and international human rights organizations in drafting the law.

- Publicly and regularly disclose (such as every six months) contributions received to any government fund, and issue a directive requiring high-level ministers and bureaucrats to also declare income sources.

- End arbitrary bans on freedom of association and peaceful assembly, and revise existing legislation on demonstrations so that any restrictions on these freedoms are absolutely necessary for public order and proportionate to the circumstances.

- Discipline or prosecute, as appropriate, members of the security forces responsible for excessive use of force, including unjustified use of lethal force, during the January 2014 protests.

- Create a tripartite minimum-wage-setting mechanism to periodically review and recommend minimum wage adjustments. The minimum-wage-setting mechanism should include worker representatives drawn from independent union federations and have a third party neutral observer to report on the proceedings.

- Ratify ILO Conventions No. 158 on Termination of Employment at the Initiative of the Employer; No. 183 on Maternity Protection (2000); and No. 131 on Minimum Wage Fixing (1983).

To International Brands

On transparency and approach to subcontractor factories

- Publicly disclose all authorized production units on a regular (such as semi-annual) basis, indicate the level of production (for example, whether the unit is a small, medium, or large supplier), and disclose when the unit was most recently inspected by independent monitors.

- Create a whistleblower protection system for workers and union representatives who alert the brand to unauthorized subcontracting. The system should ensure that all workers and union representatives receive appropriate protection for a reasonable period, including legal representation to defend themselves against vexatious lawsuits or criminal complaints filed by factories; monthly wages including the minimum wage, reasonable allowances, and overtime pay; and, where workers are dismissed from work soon after reporting the subcontract, possible alternative employment at a nearby location.

- Ensure that unauthorized subcontractor factories brought to brand attention are reported to BFC’s monitoring and advisory services. Where feasible and appropriate, the brand should contribute toward monitoring and remediation for a reasonable period before stopping production or terminating business relationships.

- Ensure that all factories that have subcontracted work without authorization over a particular period (for example, the past year) are reported to BFC for monitoring and advisory services, irrespective of whether the factory currently undertakes subcontracted production for the brand.

- Ensure that unauthorized subcontractor factories brought to brand attention are formally reported to the Labor Ministry for monitoring and enforcement action.

- Advocate with BFC to publicly list the names of brands that source from the factories that BFC monitors in order to facilitate greater transparency in brand supply chains.

- Revise the Code of Conduct for Suppliers to protect workers in subcontractor factories.

On labor compliance and industrial relations

- Register all authorized production units with BFC (including those without export licenses) and improve purchase and use of BFC’s factory monitoring and advisory services.

- Ensure that pricing and sourcing contracts adequately reflect and incorporate the cost to suppliers of labor, health, and safety compliance. This should include the cost of minimum wage salaries, overtime payments, and benefits. These efforts should be undertaken in consultation with worker rights groups and independent unions.

- Review the Code of Conduct for Suppliers and, if not already specified in the code, add provisions on the following:

- A clause that forbids illegal use of casual contracts and FDCs, including as a method of bypassing labor protections.

- Language limiting the use of FDCs to seasonal or temporary work for all workers and incentivizing the adoption of undetermined duration contracts. Communicate with all suppliers that primarily employing male workers only on short-term FDCs is discriminatory.

- A clause drawing a distinction between reasonable and unreasonable production targets that disregard worker rights.

- Ensure that suppliers set productivity targets that allow adequate breaks during the work day in accordance with basic human rights and dignity, including breaks for rest, drinks of water, and use of restrooms, and that increases in minimum wages do not result in intensified and unreasonable demands on workers.

- Develop or enhance collaboration with local stakeholders to eliminate child labor in garment factories, including by working with government officials, the ILO, NGOs, and others. The initiatives should focus on preventing child labor through improved access to primary and secondary education and alternative skill-building programs.

To Better Factories Cambodia

- Develop an alternative funding model and a time-bound plan to share Better Factories Cambodia (BFC) factory monitoring reports with factory unions. In the interim, disseminate factory monitoring report findings to unions and at least those workers who are part of BFC off-site and on-site discussions.

- Disseminate information from the Transparency Database Critical Issues Factories’ List to unions and workers in accessible and appropriate formats.

- Develop guidelines, in consultation with workers, independent union representatives, and labor rights activists, aimed at strengthening mechanisms for off-site interviews with workers in the course of BFC factory-level monitoring.

- Outline and implement a time-bound plan for expanding mandatory monitoring to all garment and footwear factories, irrespective of whether they have export-licenses.

- Expand the list of low-compliance factories on the Transparency Database to include the bottom 20 percent of factories performing poorly.

- Expand the information tracked in the Transparency Database to include the following:

- The names of the sourcing brands.

- Whether the factory purchased BFC advisory services.

- Whether BFC has notified the concerned brands of labor rights violations and, if so, any responses BFC received from brands.

- Whether brands made a financial contribution toward factory purchase of advisory services and what percentage of the costs they covered.

- Progress on remediation and brand contribution toward remediation.

- Include the names of brands that source from BFC-monitored factories on the public list of BFC-monitored factories.

-

Create

a public Transparency Database for Brands that periodically updates information

on the following:

- The number of BFC monitoring reports that brands have purchased annually and the names of the factories concerned.

- The number of brands that have contributed toward purchase of advisory services by supplier or subcontractor factories, and the percentage of the overall costs paid by brands in each instance.

- The names of brands that have not responded to BFC’s invitations to subscribe to BFC monitoring services or have failed to respond to BFC concerns about individual supplier factories.

- Conduct a study of forced overtime, the use of production quotas, and factory moves to piece-rate wages following minimum wage increases.

To the Garment Manufacturers Association of Cambodia

- Publicly and regularly disclose and make available on the Garment Manufacturers Association of Cambodia (GMAC) website an updated list of all GMAC members, including subcontractor factory members.

- Adopt and make public written policies prohibiting the illegal use of FDCs and discriminatory action against workers, such as disciplining or dismissing workers based on pregnancy or union membership.

- Adopt and make public a written policy detailing penalties to be imposed by GMAC on factory members listed as low-compliance in the BFC Transparency Database, including fines, loss of privileges, and suspension of company officials from leadership positions in GMAC and the company from general membership in GMAC. The suspensions should remain in place until the company is taken off the low compliance list.

- Adopt and make public a policy imposing penalties on GMAC member companies that do not comply with Arbitration Council findings that the companies engaged in anti-union practices.

- Support awareness programs in member factories against sexual harassment and other forms of harassment at the workplace.

To Unions

- Promote and create avenues for women’s equal participation in union leadership at the factory, federation, and confederation levels, including through adoption of new union policies.

- Create gender committees at the factory level and provide training to workers about specific gender-related workplace concerns, including sexual harassment at the workplace.

- Develop procedures to allow home-based garment workers to join unions and be represented in collective bargaining agreements.

To the EU, US, Canada, Japan, and Other Countries Whose Apparel and Footwear Companies Source from Cambodia

- Enact legislation or regulations to require international apparel buyers domiciled in the country to periodically disclose and update the names of their global suppliers and subcontractors, and, to provide updates on the status of any inspections by independent monitors as of the date of disclosure.

- Adopt a sourcing policy for government procurement which, among other things, requires companies to disclose and update the names of their global suppliers and subcontractors, and, to provide updates on the status of any inspections by independent monitors as of the date of disclosure.

- All EU member-countries should take steps to incorporate the 2014 EU Directive on disclosure of non-financial and diversity information into national law swiftly.

- Support a proposal at the ILO Governing Body for standard setting on “violence against women and men in the world of work,” where the definition of gender-based violence specifically includes sexual harassment.

To the ILO, UN agencies, the World Bank Group, Asian Development Bank, and Other Multilateral and Bilateral Donors to Cambodia

- Work with BFC to implement the above recommendations and consider funding the progressive expansion of BFC to ensure that its monitoring and advisory services programs extend to all factories, regardless of whether or not they have export permits.

- Create, in consultation with labor rights activists and workers, a special awareness program and technical guidance to prevent and seek redress against sexual harassment and other forms of harassment at the workplace.

- Actively encourage women’s participation in union leadership and encourage training, awareness-generation, and the development of factory-level complaints mechanisms against sexual harassment at the workplace.

- Assist ILO efforts to strengthen the capacity, transparency, and accountability of the Cambodian Ministry of Labor and Vocational Training to implement the above recommendations, including evaluation of the labor inspectorate through joint inspections with BFC.

- Periodically commission studies to analyze trends in apparel prices, wages, and cost of living in major apparel exporting countries to facilitate the comparison of international apparel brands’ pricing and to encourage good practice.

- Support a survey of Cambodian home-based workers, including home-based garment workers, to ensure that such workers are counted and their labor rights addressed.

- Undertake due diligence on government and private sector projects in Cambodia to ensure that projects or funding do not directly or indirectly support labor rights violations. This should include assessing the labor rights risks of each activity prior to project approval and throughout the life of the project, identifying measures to avoid or mitigate risks, and comprehensively supervising the projects including through independent third-party reporting when risks are identified.

I. Methodology

This report is based on seven weeks of interviews in Cambodia conducted between November and December 2013, and March and April 2014; phone interviews in August 2014, October 2014, and January 2015; and secondary research between October 2013 and February 2015.

Interviews took place in Phnom Penh, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Kampong Cham, and Prey Veng provinces.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 342 people, including:

- A total of 270 garment workers including 40 factory-level union representatives from 71 garment factories and 2 footwear factories. We conducted 25 of those interviews one-on-one with the workers; the rest stemmed from 37 group interviews. About 80 percent of the workers we interviewed were women; 11 workers were children below age 18.

- Two independent confederation representatives, 10 independent union federation leaders, 11 labor rights activists, and 2 representatives from the Arbitration Council.

- Two mothers of children working in a garment factory.

- Two factory infirmary workers and 2 private health providers.

- Twenty-five home-based workers who did seasonal work for garment factories.

- Five factory representatives, including 2 office-bearers of the Garment Manufacturers Association of Cambodia (GMAC).

- Individual and group interviews with 9 Cambodian government officials from the Labor Ministry; and interviews with 2 former government labor inspectors.

We interviewed some workers, union representatives, and Labor Ministry officials multiple times.

To supplement formal interviews, Human Rights Watch had informal conversations with more than 25 others with relevant knowledge, including labor rights experts and staff from local and international NGOs, the ILO, donor countries, and the UN.

We identified workers to interview with the assistance of local NGOs and independent union federations, as well as via chain referrals from workers themselves.

Worker interviews took place after their factory workday, during the lunch hour, or on Sundays, their day off. The interviews were conducted in local NGO offices, garment workers’ homes, or in restaurants or shacks around the factory that workers identified as safe. No interviews were conducted in the presence of workers’ employers, such as factory managers or other administrative staff.

All participants were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways the information would be used. Each orally consented to be interviewed. Interviews lasted between thirty minutes and two hours and were mostly conducted in Khmer with translation into English. We primarily used female interpreters. Interviewees did not receive any material compensation. Some workers were reimbursed the cost of transport to and from the interview.

The names of all workers interviewed for this report have been withheld or substituted with pseudonyms in the interest of the security of the individuals concerned. All incidents cited in the report occurred during or after 2013, unless expressly stated otherwise.

Factory names have been withheld to minimize the risk to the workers we interviewed. We assigned numbers 1 to 73 to each of the factories where we interviewed one or more workers. Letters A to Q have been used to label another 17 factories (both direct suppliers and subcontractors) that workers named in their accounts, but from which we have no worker interviews.

Between March and September 2014, Human Rights Watch sent two letters each to six international clothing and footwear brands that source from Cambodia for additional information about their approaches to labor rights in the supply chain, to present preliminary findings of our research, and to request meetings with company officials, as described below:

- Adidas Group (Adidas) provided detailed written responses to both letters, and met with Human Rights Watch in Bangkok in September 2014.

- The Armani Group (Armani) did not respond to any letters or several follow-up letters.

- Gap Inc. (Gap) responded in writing to both letters and a Gap representative had a phone discussion with Human Rights Watch in October 2014.

- H&M Hennes & Mauritz AB (H&M) provided a detailed written response to our first letter, responded in writing to the second letter, and met with Human Rights Watch in Bangkok in September 2014.

- Loblaw Cos. Ltd. (which owns Joe Fresh) did not respond to our first letter or to several follow-up letters. After we sent the second letter, they responded in writing to both letters.

- Marks and Spencer did not respond to our first letter or to several follow-up letters. After we sent the second letter, they responded in writing to both letters. They declined our invitation for a discussion and offered to respond in writing to any additional questions but did not respond to a follow-up email as of February 11, 2015.

This report is not a thorough investigation of any one brand’s entire supply chain. Not all brands named in this report were sourcing from each of the 73 factories. Human Rights Watch does not have complete brand information for every factory, which can frequently change.

Of the 73 factories:

- Based on information publicly disclosed by H&M in 2013 and 2014, 11 factories were authorized manufacturers for H&M.

- Based on information publicly disclosed by Adidas and information that Adidas gave Human Rights Watch about its past suppliers, seven factories were authorized manufacturers.

- Marks and Spencer, Gap, Armani, and Joe Fresh have neither publicly disclosed the names of factories they source from nor furnished the information when we requested it. Based on information gathered by Human Rights Watch, thirteen factories appeared to produce regularly for Marks and Spencer, seven factories appeared to produce regularly for Joe Fresh, five factories produced for Gap, and one factory produced regularly for Armani.

In order to reflect the perspectives of factories in this report, we emailed questionnaires to 58 factories using contact information listed on the GMAC member database. These factories were chosen at random and included direct suppliers and subcontractors. Two factories responded—one in writing and the second through a meeting.

In November 2014, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Ministry of Labor and the Ministry of Commerce, outlining our findings and seeking a written response. By publication we received a response only from the Labor Ministry, which is reflected in the report.

Human Rights Watch correspondence and replies by brands and government ministries can be found at http://www.hrw.org.

Human Rights Watch also gathered information about which brands were produced in factories wherever this information was relevant and available from independent federations—the Coalition of Cambodian Apparel Workers Democratic Union (CCAWDU), the National Independent Federation of Textile Unions in Cambodia (NIFTUC), the Collective Union of Movement of Workers (CUMW), the Cambodian Alliance of Trade Unions (CATU), and a local nongovernmental organization—the Community Legal Education Center (CLEC). We were also able to access the Worker Information Center labels database from 2012 and 2013.

II. Background

Cambodia’s Garment Industry

Although Cambodia’s share of global exports of garments and textiles is relatively small, it is extremely important to Cambodia’s economy, which has a gross domestic product of US$15.35 billion.[2] The country’s global exports in 2013 amounted to roughly $6.48 billion, of which garment and textile exports accounted for $4.97 billion and shoe exports accounted for another $0.35 billion.[3] In 2014, garment exports reportedly totaled $5.7 billion.[4]

Cambodia entered the export-oriented global garment and textile industry in the 1990s. It benefitted from government promotion of foreign direct investments through tax holidays and duty-free imports of machinery and materials.[5]

Between 1995 and 2006, bilateral trade agreements with the United States, the European Union, and Canada spurred the garment industry’s growth. The US, EU, Canada, and Japan are the largest importers of Cambodian garments and textiles and shoes.[6] Except for the downturn resulting from the 2008 global economic crisis, the industry has grown consistently.

The Cambodian garment industry is largely foreign-owned, with investors largely from Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, and South Korea.[7] Less than 10 percent of factories are owned by Cambodians.[8]

A majority of factories undertake “cut-make-trim” functions—manufacturing clothes from imported textiles based on designs provided by international buyers.[9] Phnom Penh, the capital, is a hub for garment factories, but garment factories have mushroomed elsewhere, notably in adjoining Kandal province. Factories vary in size and operations, ranging from those with more than 8,000 workers with export licenses that directly supply international apparel buyers to small, unmarked factories with fewer than 100 workers that subcontract for larger factories.[10]

Women workers dominate the garment sector. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that women comprise about 90 to 92 percent of Cambodia’s garment sector.[11]

According to July 2014 government data reported in the media, Cambodia’s 1,200 garment businesses employ 733,300 workers.[12] This figure does not include home-based workers.[13]

Key Actors Influencing Labor Conditions

Manufacturers, government officials, trade union representatives, international buyers, and third-party monitors all influence labor practices in Cambodia’s garment industry.

The Cambodian Labor Ministry sets policy and its labor inspectorate is responsible for monitoring and compliance. The 1997 Cambodian Labor Law governs all garment factories irrespective of their size.[14] It regulates working conditions in factories, including through rules governing overtime work, minimum age of work in factories, pregnant workers, and leave. All factories with more than eight workers should have internal regulations governing working conditions. The Labor Ministry has issued model internal regulations. Even though the law has strong protections for workers on many subjects, its enforcement—as described below—has been abysmal, in large part because of an ineffectual labor inspectorate crippled by corruption and outpaced by factory growth.[15]

Independent trade unions play an important role in improving conditions through collective bargaining agreements, reporting labor rights violations, and helping workers seek redress. A 2014 report shows that 29 percent of the 371 factories surveyed had no unions; 42 percent had one union; 17 percent had two unions; and 12 percent of the factories had between three and five unions.[16]

According to June 2013 data compiled by the Cambodia-based staff of the Solidarity Center, an international labor rights group, there at least 63 garment trade union federations in Cambodia,[17] of which only a handful are considered independent. Workers and activists widely believe the rest to be pro-management and pro-government “yellow unions.”[18]

Unions can bring complaints affecting workers before the Arbitration Council, whose arbiters interpret the Labor Law to decide disputes. The Arbitration Council’s decisions are considered authoritative interpretations of the Labor Law and its applications. The decisions can also be binding depending on the nature of the dispute and the parties involved.

Another key player is the Garment Manufacturers Association of Cambodia (GMAC), which has more than 600 operational factory-members.[19] GMAC is the most powerful, well-organized employer association influencing labor conditions. For example, it is represented on tripartite bodies like the Labor Advisory Committee, takes public and vocal positions on policy issues like the minimum wage and use of short-term contracts; and plays a critical role in influencing industrial relations. While many of GMAC’s positions appear in conflict with worker rights, it has in the past taken measures aimed at improving working conditions. For example, GMAC signed a memorandum with several union confederations where parties agreed to treat arbitral awards as binding.[20] In December 2014, GMAC signed an agreement to help eradicate child labor in Cambodia’s garment industry.[21]

Cambodia also has an important third-party monitor—the Better Factories Cambodia (BFC) program—created in response to the 1999 US-Cambodia bilateral trade agreement that linked annual import quotas to demonstrable improvements in labor conditions in garment factories.[22]

Better Factories Cambodia

The 2001 BFC program—now a partnership between the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and ILO— remains the most important third-party monitor of labor conditions in Cambodia’s garment factories,[23] despite having lost clout when trade-related incentives expired in 2005.[24]

Garment manufacturers must participate in BFC’s factory monitoring program to get Cambodian government export licenses. According to January 2015 data, BFC monitors 536 garment and 12 footwear factories.[25]

The level of transparency in BFC’s reporting on factory conditions has varied over time. Initially, BFC publicly named factories and key labor rights problems as part of its biannual reports, with follow-up reports outlining remedial measures the factories had taken. Since 2005-2006, BFC no longer publishes its factory-specific findings and instead provides an overview of working conditions of factories surveyed through synthesis reports. It makes its factory-level monitoring reports available to factories free of cost, and other third parties, for example international brands, at a cost.[26] Third parties—including labor unions and NGOs—cannot access these reports unless the factory authorizes such access and the third parties pay a fee to BFC.

Labor rights groups have criticized BFC’s changes and called for greater transparency in its monitoring and reporting methods.[27] Despite pressure from the government and garment manufacturers to keep names of non-compliant factory confidential, in March 2014, BFC launched its Transparency Database, which publicly names the 10 “low compliance” factories every three months.[28]

Brands can participate in BFC in different ways. They can endorse BFC, buy BFC’s monitoring reports, and join in BFC’s buyers’ forum, a platform that brings together buyers, government authorities, factories, and unions to discuss key concerns and possible ways forward. They can also purchase BFC’s training and advisory services. According to January 2015 data, about 40 of the 200 brands representing 60 percent of the orders placed in Cambodia endorsed BFC.[29]

BFC has been a model for the IFC-ILO Better Work Program that operates in other garment-producing countries, including Vietnam, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Haiti.[30]

International Apparel Buyers

Many top apparel brands including H&M, Marks and Spencer, Adidas, and Gap source their products from factories in Cambodia. Many brands attempt to demonstrate their commitment to international labor standards by incorporating them in their codes of conduct. Through their own internal factory audits and engagement with external monitors like BFC, brands track labor compliance and are well-placed to exert pressure on suppliers to make changes. Some brands also undertake such monitoring for subcontractors. They may also set up grievance redress mechanisms to respond to complaints by workers employed by their suppliers and subcontractors.

International apparel buyers also play an important role in demanding that labor conditions meet international standards and in applying pressure on the Cambodian government to enforce the Labor Law, including through public and private advocacy.[31] As noted earlier, brands can also actively engage with third-party monitors like BFC.

A buyer’s pricing and purchasing practices can contribute to robust or poor labor conditions.[32] For example, when an international buyer places frequent orders or makes last-minute changes without adequate turnaround time, the additional pressure may contribute to factories exacting excessive and forced overtime from workers.[33] Ken Loo, the secretary general of GMAC, described how buyers’ refusal to adjust their prices after a minimum wage increase impacted factories:

By the end of December [2013], buyers have committed to contracts [with suppliers] till May or June [2014]. The contract is signed on the previous price. The minimum wages have been raised. But the brands are not willing to renegotiate the price.[34]

Factories may then pass the cost on to workers through higher—and what workers describe as unattainable—production targets, making labor rights violations more likely.

Recent Flashpoints in Cambodia’s Garment Industry

Over the last few years, repeated incidents in which scores of garment workers fainted while working, industry-wide protests over minimum wages, and an extremely hostile environment for independent unions in Cambodia have raised the profile of problems in the garment industry among labor rights advocates locally and globally.

Building and fire safety have come under more scrutiny following the partial collapse of structures in two factories in 2013, resulting in the death of two workers, and a factory fire in July 2014.[35] A spate of mass fainting among Cambodian garment workers led the Labor Ministry to form a committee in August 2014 to investigate the cause of these faintings.[36]

Against this backdrop, protests for an adequate minimum wage rocked the Cambodian garment industry in December 2013. GMAC advised its member-factories to suspend operations, straining already tense labor relations. On December 31, 2013, the Labor Ministry increased the minimum wage to $100 per month from $80 effective February 1, 2014.[37]

On January 2, 2014, workers defied a government deadline to end protests and demonstrated, demanding $160 as minimum wage. Workers cited a December 2013 tripartite government-constituted task force report that estimated that a living wage should fall between $157 and $177 in support of their demands.

Overnight on January 2 and 3, hundreds of police and gendarmes were deployed to clear workers protesting. Violent clashes broke out with some protesters. On the morning of January 3, the authorities sent a large force of gendarmes to seize control of the area, some of whom fired their assault rifles towards the crowds, killing six people. A person beaten by gendarmes later died of his injuries. Twenty-three human rights defenders and workers arrested during these incidents were later charged with responsibility for the violence, tried and convicted, and sentenced to prison terms, despite there being no evidence against them. Their sentences were all suspended, but they remain at risk of imprisonment.[38] No gendarmes were prosecuted.

International outrage followed this crushing of the garment worker protests and arrests. Many international brands wrote to the Cambodian government requesting that it initiate an investigation into government violence and also create a wage-setting policy.[39] A new government committee led by a former minister of economy and finance began work in January on a new minimum wage policy.

Meanwhile, independent trade unions alleged that the government had suspended new union registrations after the January protests.[40] Talks around the hike in minimum wages were ongoing since January 2014 with strained industrial relations between factories and unions. In September 2014, days before another round of negotiation on minimum wages, the government announced that it was initiating a criminal investigation against six independent union leaders and summoned them to appear before a court.[41] Soon after, independent unions and labor rights groups launched a new advocacy campaign demanding a monthly minimum wage of $177.[42] In November 2014, the Cambodian government announced a revised minimum wage of $128 effective January 2015.[43]

III. Hiring Practices and “Flexible” Labor Arrangements

[W]hile it is true that buyer demand fluctuates, it typically does not drop at the end of a worker’s contract and pick up significantly a week later. There is a difference between a genuine change in buyer demand, and the use of this pretext to deny benefits to workers.

—ILO, “Practical challenges for maternity protection in the Cambodian garment industry,” 2012, p. 15.

Many factories hire workers on fixed-duration contracts or on other casual bases when there is no justification for doing so, such as seasonal labor demands or other temporary business needs. Workers repeatedly hired on short-term contracts or on a casual basis are more likely to experience the labor abuses documented in this report. They have a lower likelihood of redress and are at a greater risk of experiencing union discrimination, pregnancy-based discrimination, and denial of maternity benefits and sick leave.

Repeated Use of Short-Term Contracts

The illegal use of short-term contracts is common in Cambodia’s garment industry. The threat of non-renewal of such contracts fosters an environment in which factory managers can exploit workers, and workers are too scared to complain for fear of losing their jobs. Use of short-term contracts is often a barrier to healthy workplace conditions, and can facilitate anti-union discrimination, pregnancy-based discrimination, and forced overtime work.[44]

Cambodian labor law permits factory managers to engage workers either on open-ended contracts of undetermined duration (UDC) or on fixed-duration contracts (FDC) that specify an end-date. The Labor Law states that factory managers can issue short-term contracts and renew them one or more times for up to two years.[45]

In theory, workers on FDCs enjoy many of the same benefits that workers on UDCs enjoy, though they have less protection against dismissal. Workers on UDCs and FDCs who have at least one year’s uninterrupted service in a factory are entitled to maternity pay and a seniority bonus. The seniority bonus increases annually and is directly linked to job tenure.[46] A key difference is that workers on FDCs are entitled to least 5 percent of their wages as severance at the end of each contractual period or when they are terminated.[47] Factories pay severance for UDC workers only at the end of their employment.

Workers on UDCs have longer notice periods and heavier penalties assessed against employers for unfair dismissals from work.[48] A manager can refuse to renew an FDC without having to give any reason.[49]

Workers have challenged the abusive use of FDCs in collective disputes before the Arbitration Council. The Council has consistently ruled that according to article 67 of the Labor Law, factories cannot engage workers on FDCs beyond two years and that if they do, such workers are entitled to the same benefits and protections as workers on UDCs.[50]

The Garment Manufacturers Association in Cambodia (GMAC) has contested the Arbitration Council’s interpretation of the Labor Law.[51] In March 2014, Ken Loo, the secretary general of GMAC told Human Rights Watch that “very few” employers repeatedly used FDCs, describing them as the “black sheep” of the garment industry. Explaining the use of FDCs, Ken Loo said, “How can we afford to guarantee job security when our buyers place orders seasonally? I don’t know if my buyers will place orders again.”[52] Human Rights Watch research for this report, however, corroborated by information given by some international apparel brands (discussed in detail below), shows that even factories with assured business use FDCs in ways that appear to contravene the Labor Law.

The Cambodian government has in the past supported GMAC’s position on the repeated use of short-term contracts and has not made monitoring for illegal use of FDCs a priority in its inspections or enforcement measures.For example, Human Rights Watch reviewed the labor inspectorate reports for a factory where all workers were repeatedly issued short-term contracts and found no documentation of the length of the contracts or any assessment of why the factory’s entire workforce was on such contracts.[53] In December 2014, Labor Ministry officials responded to Human Rights Watch’s written concerns about the repeated use of FDCs stating, “[a]s there has been disputation about the interpretation and comprehension of the Labour Law, the result has been that each party has made an interpretation of these provisions in order to serve their own interests.”[54]

Proliferation of FDCs

Human Rights Watch found that many factories issued FDCs to workers who had been working in the factory for more than two years.[55] The duration of the short-term contracts varied from twenty-one days to one year, with three or six-month contracts the most common.[56] Some newer factories appeared to hire their entire workforce on FDCs without basing it on any apparent seasonal or temporary business needs.[57] In some factories, workers said men were hired on shorter term contracts than their female counterparts and believed it was to discourage men’s participation in factory unions.[58] Some factories changed worker contracts en masse from UDCs to FDCs, ostensibly because the factory management had changed.[59]

Survey data shows that factories use FDCs in violation of Cambodian labor law. The Better Factories Cambodia (BFC) reported a drop in factories complying with the two-year rule on FDCs from 76 percent of factories surveyed in 2011 to 67 percent of factories surveyed in 2013-2014.[60] Since 2011, BFC has also consistently found that nearly a third of all factories in each survey period used FDCs to avoid paying maternity and seniority benefits.[61]

The Worker Rights Consortium (WRC), an international labor rights organization, conducted a survey of 127 factories, including 119 GMAC members, between August 2012 and May 2013. The survey results found that nearly 80 percent of factories employ “most or all of their workers on FDCs” and “at least 72% violate the labor law’s two-year limit on successive FDCs.”[62]

Bent Gehrt, WRC’s Southeast Asia field director, told Human Rights Watch that many factories falsely claim they need to use FDCs because of fluctuating buyer demand. For instance, WRC found that MSI Garment (now closed), claimed fluctuating orders forced it to hire more than half of its 1,600 workers on repeated three-month FDCs. But upon close examination, WRC representatives found that its monthly employment figures for 2006 fluctuated by less than 50 from an average of 1,600 workers over the course of the entire year. Gehrt, while stressing that using UDCs does not hinder factories in laying off people when they have a valid reason, explained that if the fluctuating orders were the reason then factories should use the lowest number of workers employed in the preceding 12 months as a baseline and issue UDCs to all workers up to that baseline.[63]

Some proponents of FDCs from the business sector point out that workers themselves often demand FDCs. Ken Loo, the GMAC secretary general, suggested that independent unions were not accurately representing workers’ demands. He said, “Over the last three years we have not really seen cases where workers are demanding UDCs. Now workers are demanding FDCs.” He also said, “Workers know crystal clear what they are signing at the dotted line. So I really don’t understand how a worker hired on an FDC can want a UDC.”[64]

Contrary to GMAC’s assertions, in almost all cases where Human Rights Watch discussed worker contracts in detail, workers said they had no choice regarding their employment contract.[65] Many workers had no information about a written contract—they started working and were orally informed about their wages. For example, Cheng Thai, in her mid-20s, from factory 11, said, “They just told me I would be on a monthly wage. I didn’t sign any contract and don’t know my employment status.”[66]

Where workers said they had a written contract, they were called to the factory office and asked to affix their thumbprint on a document. Sren Seang’s experience in factory 9 is similar to that of most workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch: