Summary

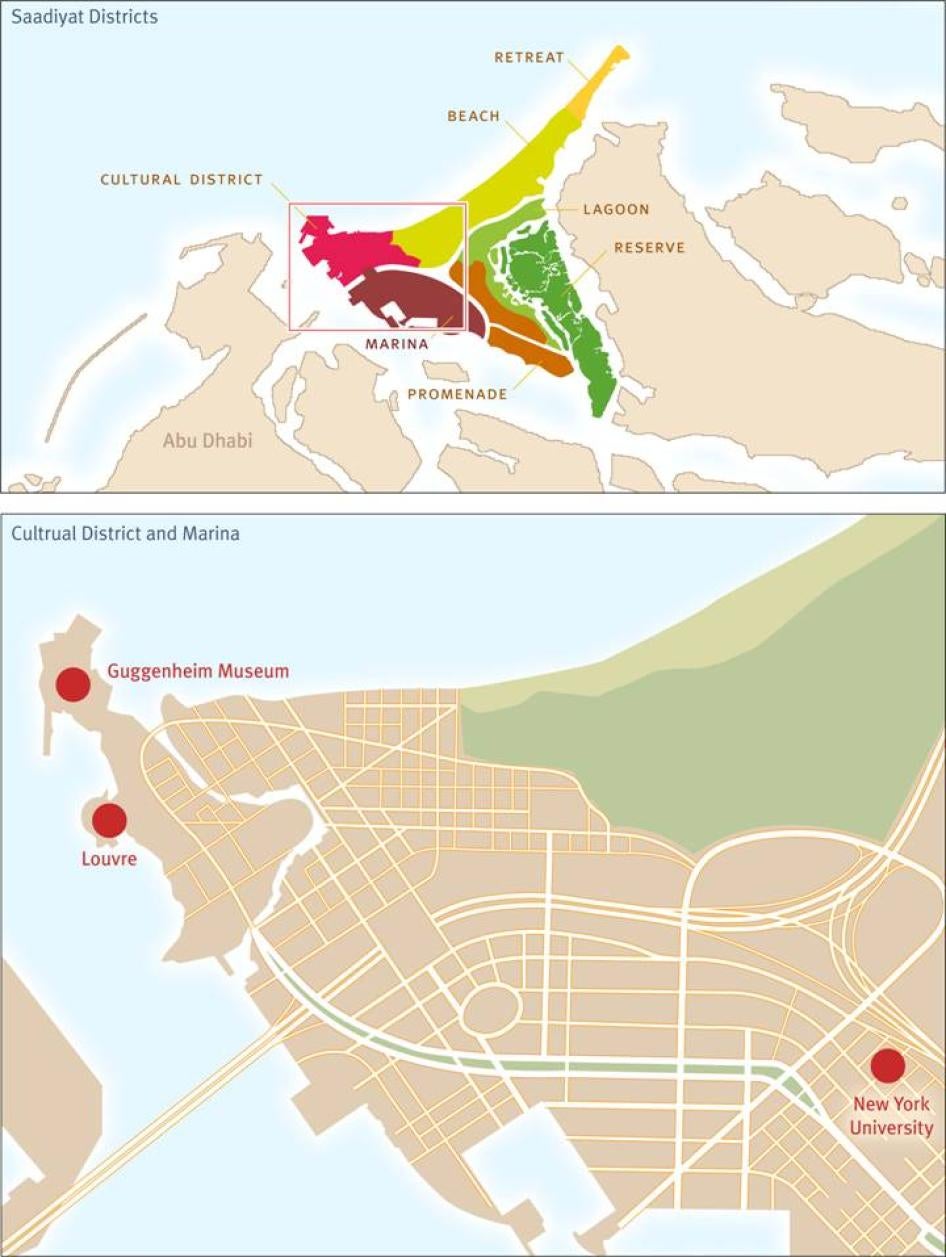

The Gulf emirate of Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has been working to convert Saadiyat Island into an international tourist destination, at a cost of between US$22 and $27 billion. The low-lying island in the Arabian Gulf will get a campus of New York University (NYU), museums, including branches of the Guggenheim and the Louvre, and a performing arts center, each designed by world-renowned architectural firms, as well as golf courses, hotels, and luxury residences. The Tourism Development and Investment Company of Abu Dhabi (TDIC), a government-established and owned development company, is the primary development partner on the island; cultural institutions, including the Guggenheim and Louvre museums, have signed agreements with TDIC to develop outposts there. In January 2012 TDIC announced a new time frame for the museums, which have faced lengthy construction delays. The Louvre Abu Dhabi is now scheduled to open in 2015, while the Guggenheim is set for 2017. Abu Dhabi’s Executive Affairs Authority (EAA), a government agency that provides strategic policy advice to the Chairman of the Abu Dhabi Executive Council, is responsible for the development and construction of the NYU campus, scheduled to open in 2014.

Between October 2010 and January 2011 Human Rights Watch visited Saadiyat Island several times to update the findings of its May 2009 report, The Island of Happiness: Exploitation of Migrant Workers on Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi, which documented the severe exploitation and abuse of South Asian migrant workers on the island, and the lack of legal and institutional protections necessary to curtail the abuse.

Our research, based on interviews with 47 workers on the island, found that in spite of commitments by both the developers and their foreign partners to take steps to avoid abuse of migrant workers on Saadiyat Island, and in spite of some improvements in the working conditions of migrant workers, abuses are continuing. This new report documents both these continuing abuses and the gaps in protection that must be addressed in order to remedy them.

Our research found notable improvements in some areas, particularly in the regular payment of wages, rest breaks and days off, and employer-paid medical insurance. However, workers continue to report indebtedness for recruitment fees paid to obtain their jobs in the UAE. In some cases, they had paid fees just a few months before arriving in Abu Dhabi to obtain their most recent employment contracts.

Workers also reported a lack of information, or misleading information, about their terms of employment before arrival in the UAE, or the imposition of new, inferior contractual terms upon arrival; illegal salary deductions; and, for some workers who did not live in the Saadiyat Island Workers’ Village, overcrowded and unhygienic housing conditions. Contrary to commitments of the developers, only one worker of the 47 we interviewed reported that he retained custody of his passport, while the rest said that their employers retained their passports.

Following the publication of our 2009 report and in line with its recommendations, many of the institutions involved in the development of Saadiyat Island started to make commitments to avoid the abuses of workers on the island, including promises to ensure prompt payment of salaries, overtime pay, days off, vacations, and improved housing standards.

Most recently, they pledged to require contractors to reimburse workers who have paid recruitment fees in their home countries and to appoint independent monitors to detect and report publicly on violations of workers’ rights on the island.

These steps have the potential to improve conditions for workers but, as the mixed picture of continuing abuse presented in this report shows, there is still considerable progress to be made. Much will depend on how the commitments are carried out in practice. The developers have not yet reported publicly on any findings by the new monitors they say they have appointed. Moreover, to date they have not made public key components of their monitoring programs (such as terms of reference, scope of monitoring, and research methodology) that might demonstrate that the monitoring is credible and independent. It is unclear if they plan to do so.

Further clarity is also needed regarding measures to ensure compliance with the new commitments. TDIC has spelled out its contractual rights to fine or terminate contractors that do not comply with the measures designed to prevent human rights abuses, but enforcement appears to be dependent on TDIC alone. It is unclear what recourse NYU, the Louvre, and the Guggenheim have should TDIC and EAA fail to enforce their own commitments to worker protections.

Since the publication of our 2009 report, the UAE government has implemented significant new labor reforms, including expanding a ban on work during the hottest hours of the day between mid-July and mid-September, andcompulsory housing standards to improve living conditions for migrant workers. In January 2011 the government issued important new labor regulations to curb exploitative recruiting agents who entrap foreign workers with recruiting fees and false contracts, signaling a very positive commitment to address two of the country's most glaring human rights problems.

The commitments and legal reforms made on Saadiyat Island are welcome developments, but the true test lies in the impact of these changes on workers. The evidence to date indicates that there are significant problems yet to be overcome and that both the government and institutions need to do more to follow through on existing commitments and expand on them to address remaining weaknesses.

Our research points to the continuing gaps in protections. A number of the important commitments made by TDIC, EAA, and their foreign partners are being weakened or ignored in practice. Absent rigorous monitoring and penalties for non-compliance, there is a high risk that conditions for workers will not change substantially and that instead abusive contractors will continue to violate standards designed to protect workers’ rights, and workers will continue to face exploitation, with inadequate information about their rights or opportunities for redress.

To avoid this outcome, the developers and their foreign partners need to do more to ensure that adequate accountability measures are put in place. Their existing commitments should be strengthened to provide for monitoring that is transparent and independent, supported by clear and public guidelines and by the disclosure of comprehensive information about the terms of reference and monitoring methodologies of their new independent monitors.

TDIC and EAA must remain vigilant by penalizing and, failing adequate response, terminating relationships with contractors who continue to confiscate passports or work with agencies or sub-agencies that mislead workers regarding conditions of employment in the UAE, and should publicly disclose these penalties and terminations.

In light of the continued prevalence of workers reporting the payment of recruiting fees—the single greatest factor in creating conditions of forced labor—all parties must make a clear, unequivocal promise to ensure that workers are reimbursed any recruiting fees they are found to have paid to secure employment on the island. That way, if contractors fail in their promise, the national developers will be responsible and, as a last resort, workers can turn to them or to the foreign cultural and academic institutions for reimbursement. As between workers and these entities, there is no doubt that the national and foreign institutions are in a far better position to bear the risk and loss when contractors fail in their promise to pay such fees. Finally, NYU, Guggenheim, and the Louvre should obtain and disclose enforceable guarantees from EAA and TDIC, respectively, to uphold their commitments to protecting worker rights.

Key Recommendations

- TDIC and EAA should monitor compliance by contractors and subcontractors through an independent and transparent process that includes interviews with workers in their native language. They should penalize contractors working with agents or sub-agents who are found to have charged workers recruitment fees, and should terminate relationships with contractors that continue to work with agencies or sub-agencies that charge workers fees. The penalties should be severe enough to act as deterrent rather than a routine cost of business. The Guggenheim, the Louvre/AFM, and NYU should seek regular updates on compliance and insist that their development partners enforce penalties for violations and terminate relationships with repeat violators.

- TDIC and the EAA should explicitly commit to reimbursing workers for any recruiting fees they are found to have paid when contractors have failed to do so. If TDIC or the EAA also fails to fulfill this obligation, NYU, the Guggenheim and AFM/the Louvre should step in to reimburse any outstanding recruitment fees paid by workers on their respective sites.

- TDIC and EAA should require all contractors and subcontractors to obtain copies of contracts signed by workers in their home countries, in their native languages, attesting to the terms of their employment. If workers have already held jobs in the UAE and are recruited in-country, contractors should provide signed and notarized undertakings in workers’ native languages that clearly state the terms and conditions of their employment.

- TDIC and EAA should immediately require all contractors, subcontractors, and labor suppliers to return workers’ passports to their physical possession.

- TDIC and EAA should penalize contractors, subcontractors, or labor suppliers who are found to have confiscated passports, and should terminate relationships with those that continue to do so. The Guggenheim, the Louvre/AFM, and NYU should seek regular updates on compliance and insist that their development partners enforce penalties for violations and terminate relationships with repeat violators.

- TDIC and the EAA should release comprehensive information about the terms of reference and methodologies of the monitoring firms they have engaged to demonstrate their respective firms’ independence in auditing and reporting.

I. Background

Human Rights Watch’s 2009 “Island of Happiness” Report

Human Rights Watch’s May 2009 report, The Island of Happiness: Exploitation of Migrant Workers on Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi, documented a pattern of severe exploitation and abuse of South Asian migrant workers in the showcase developments on Saadiyat Island in the Gulf emirate of Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Almost all of the 94 migrant workers interviewed for the report said they paid recruitment fees of up to US$4,100, or between one and three years’ of their home countries’ annual Gross Domestic Products (GDP) per capita, to recruitment agencies in order to obtain their jobs in the UAE. With meager incomes and few assets, workers often took out loans at high monthly interest rates in order to pay these fees, which they then spent months or years working to pay back.

Once in the UAE, many workers we interviewed found that their employers required them to sign new agreements. Some found that recruiting agents had misinformed them about the types of job they would have, or the terms of employment, while others faced exploitation or abuse from their employers in the UAE. Like other migrant workers in the UAE all were denied the right to change jobs under the UAE’s restrictive immigration sponsorship laws. Workers interviewed said that employers universally confiscated passports from migrant workers.

The report called on the relevant local authorities, including the Tourism Development and Investment Company of Abu Dhabi (TDIC) and Abu Dhabi’s Executive Affairs Authority (EAA), foreign cultural and academic institutions, including New York University (NYU), the Guggenheim, and Agence France-Muséums (AFM), the agency overseeing the Louvre Abu Dhabi, and contractors operating on the island, to uphold international human rights and labor standards and UAE laws designed to protect workers’ rights, especially with respect to confiscation of workers’ passports by employers and payment of recruitment fees by workers. Human Rights Watch asked that the institutions and their development partners guarantee minimum protections for workers to ensure that no workers on their projects should arrive in the UAE in a state of indebtedness because of payment of recruitment fees or should be unable to go home because of the confiscation of their passports. Such

practices violate existing UAE laws and court rulings, which employers frequently flout in practice with no consequence from the authorities. To address this lack of accountability, as well as the failure of the UAE government to require public disclosure of death and injury rates at worksites, we further called upon the companies and institutions involved to institute a rigorous independent monitoring program to detect and report publicly on violations of workers’ rights and health and safety conditions and records.Lastly, the report called on these institutions to establish clear mechanisms for redress and compensation in cases where employers had violated their workers’ rights.

Responses to 2009 Report

In 2010, the EAA, TDIC, NYU and the Guggenheim issued a number of public promises to protect the workers building their sites. On February 3, 2010, NYU and the EAA publicly announced that they would require all employers associated with the NYU Abu Dhabi project to reimburse workers for any fees associated with their recruitment. The announcement also promised that employees would retain all of their personal documents, including passports, specified minimum housing standards, and reiterated requirements under UAE law including timely wage payments through bank accounts and employer-paid medical insurance.

In September 2010 the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and TDIC, the development company responsible for the bulk of Saadiyat Island construction, including museums in the Cultural District, issued a joint statement publicizing TDIC’s employment practices policy effective since July 2010 that sets certain labor standards for workers employed on the majority of Saadiyat Island projects, including the Abu Dhabi branches of the Guggenheim and Louvre museums. Human Rights Watch publicly recognized the significance of these steps.

Agence France-Muséums (AFM) and the Louvre, by contrast, have to date not publicly articulated their approach to addressing the human rights of the migrant workers building their museum, although they have given some explanations privately in response to concerns raised.In correspondence and in meetings with Human Rights Watch, they spoke of the French government’s historical commitment to protecting labor rights, and stressed that issues identified in our 2009 report remained of concern to them. They also explained that the contractual agreement between AFM and TDIC includes a requirement (that preceded our 2009 report) that workers’ conditions on the Louvre Abu Dhabi project meet the international labor standards set in the Social Accountability 8000 standard (known as SA8000), a code meant to guide companies’ compliance with internationally-recognized workers’ rights. While the reference to the Social SA 8000 in the contract is an important step toward ensuring that workers are treated fairly and in compliance with international human rights law, it remains unclear how this provision of the agreement is applied in practice. In discussions with Human Rights Watch, Louvre officials said that they will rely upon the findings of the TDIC-hired labor monitor to observe conditions on the Louvre site and, moreover, clarified that that the contractual provisions are not accompanied by an enforceable guarantee that would clearly allow AFM to take measures if it learned that the agreed standards were being disregarded.

Responsibility of Institutions for Protection of Workers’ Rights

The government of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has an obligation to protect workers from abuses. It has taken some steps to improve the country’s labor regulations to address weaknesses. Yet enforcement is lax, and workers have only limited access to legal and judicial remedies in the UAE. The authorities must do more to reduce the abuses against migrant workers on Saadiyat Island.

The private sector also must play a role in tackling human rights abuses. Although the UAE government has primary responsibility for respecting, protecting, and fulfilling human rights, businesses also have human rights responsibilities. This basic principle has achieved wide international recognition and is reflected in various norms and guidelines.[1]

The longstanding concept that businesses have human rights responsibilities secured additional support during the 2005-2011 tenure of the United Nations special representative on business and human rights, Professor John Ruggie. As elaborated in the “Protect, Respect and Remedy” framework and the “Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights” for their implementation, which were endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council, businesses should respect all human rights, avoid complicity in abuses, and adequately remedy them if they occur.[2] Elsewhere, Ruggie has explicitly noted that “[t]he corporate responsibility to respect human rights … applies across an enterprise’s activities and through its relationships with other parties, such as business partners, entities in its value chain, other non-state actors and state agents.”[3]

II. Since 2009: A Mixed Record

In October and November 2010, and again in January 2011, Human Rights Watch returned to Saadiyat Island to assess what these new policies have meant in practice for workers on the island. We interviewed 47 workers employed there, including workers from the Guggenheim and New York University (NYU) construction sites, workers constructing roads and other infrastructure servicing the Louvre site, workers from around the Cultural District (where all the museums will be housed), and workers we met elsewhere on the island.

Our new research indicates that there have been some significant improvements in problems previously documented: nearly all workers we interviewed reported that employers paid their wages into individual bank accounts, and all but one worker held medical insurance policies purchased by their employer. UAE law requires both practices. However, though at least one UAE court has ruled that employers are prohibited from confiscating worker passports, the problem of passport confiscation remained common among the workers who spoke to Human Rights Watch. Only one worker we interviewed said he retained custody of his passport, while the rest said that their employers retained their passports. And despite the newly implemented electronic payment system, designed to curb long-standing abuses vis-à-vis the non-payment of wages, some workers we spoke to reported that their employers continued to illegally deduct significant portions (up to 25 percent) of their wages each month, justified as reimbursement for their food costs.

Particularly with regard to the payment of recruitment fees, contract procedures, and redress for violations of workers’ rights, it appeared from our interviews that employment practices still failed to conform to the various commitments made by the academic and cultural institutions and their local partners. In some of the cases we researched, it additionally appeared that practices on the island continue to violate UAE law as well as international standards for labor rights and migrant workers’ rights.

Almost all of the workers we spoke to reported that they had paid high recruitment fees to obtain their jobs in the UAE. In some cases workers said they had paid these fees over three years ago, while in other cases, they had paid fees just a few months before arriving in Abu Dhabi—when the commitments to halt such practices was already in effect—to obtain their most recent employment contracts. Some workers said that they had not signed an employment contract before leaving their home countries, while others reported that, in cases where they had signed a contract in their home countries, employers required them to sign new contracts with different terms upon arrival in the UAE. Many workers reported that their jobs significantly differed from what agents had promised in their home country.

Both the Tourism Development and Investment Company of Abu Dhabi (TDIC) and Abu Dhabi’s Executive Affairs Authority (EAA) (NYU’s local partner) have paid particular attention to workers’ housing conditions, with positive effect. In its Employment Practices Policy, TDIC requires contractors working on the island to house their workers in the Saadiyat Island Construction Village, a housing facility with the capacity to house 10,000 workers as of July 2011, and with a projected capacity of 40,000 workers upon completion. The Construction Village houses a maximum of six workers in each room and boasts amenities atypical of labor camps in the UAE, including an internet café, sports and recreational facilities, entertainment programming, and laundry services.

However, many of the workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they did not live in the TDIC Workers’ Village, but instead in alternative housing facilities in the Industrial Area and elsewhere in Abu Dhabi. Human Rights Watch visited several of these other labor camps and housing facilities, where residents included employees on the Guggenheim site. Workers in these housing facilities said they were not allowed visitors, suffered from regular water shortages, complained of poor levels of cleanliness, and lived in rooms crowded beyond their intended capacity, with between 14 and 16 people per room.

Responses to our New Findings

In February 2011 Human Rights Watch presented its most recent findings in a private letter (published in the appendix below) to the main parties involved in the Saadiyat Island development project, including TDIC, the EAA, NYU, the Guggenheim, and Agence France-Muséums (AFM), and held meetings with NYU, Guggenheim, and Louvre representatives, highlighting the continuing abuses on the island and again stressing the need for independent monitoring and real remedies for workers abused by their employers and recruiting agents. While all institutions responded to the findings of our letter, their responses varied substantially in terms of the information they provided and their willingness to acknowledge and address human rights violations caused by common employer practices in the UAE. At a minimum, all the institutions reiterated a broad commitment to protecting the rights of workers on their respective sites.[4]

However, despite having taken steps to incorporate protections of workers’ rights into their contract with TDIC, the Louvre and AFM have yet to make public their own commitments (independent of TDIC) to workers’ rights on the island, including reimbursement for recruiting fees.[5] During a May 2011 meeting with officials from the French Ministry of Culture, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and AFM, Human Rights Watch asked why the government had not made commitments similar to those made by other institutions on the island.[6] Christine Gavini-Chevet, advisor to the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said, “we believe we have been transparent about our engagement….We feel that public promises won’t bear fruits.” Gavini-Chevet assured Human Rights Watch that despite evidence of ongoing worker abuses on TDIC projects on the island, the French government “trusts TDIC” to keep its promises to avoid such abuses on the Louvre project, and that “the violations [Human Rights Watch] cited are not relevant to our site because we haven’t started construction yet.”[7] In fact, when Human Rights Watch visited the Louvre Abu Dhabi construction site in October 2010, pilings on the site had already been completed, indicating that construction had proceeded further than on either the Guggenheim or NYU sites. In August 2010 TDIC and AFM each also announced that TDIC had completed placement of the final pilings for the Louvre Abu Dhabi, with TDIC describing it as a “major construction milestone.”[8]

The joint written response we received from AFM and the Louvre to our February 2011 letter described the importance they attach to workers’ rights, indicating that they “have kept encouraging and enforcing socially responsible practices within the framework of the Louvre Abu Dhabi construction site” and stressing their strong commitment to “high social standards, not only on the building site but also in the entire Louvre Abu Dhabi project.” The letter did not, however, substantively address concerns about abuses on the island. Despite voicing strong commitments to ensure that workers’ rights will be respected, AFM continued discounting the museum’s responsibility to workers: “the French party does not have the responsibility of building the museum as the contracting authority is TDIC.”[9]

Since the letter, TDIC, NYU, and the EAA made significant new pledges to hire independent monitoring firms (although TDIC indicated that it already had an “independent monitoring consultant” and had carried out 48 audits) to review and issue public reports on compliance with rules safeguarding protections of workers’ rights on their projects (discussed in greater detail below), and TDIC matched the pledge by NYU and EAA to require contractors to reimburse workers for recruitment fees (discussed in greater detail below).

These new pledges mark major progress in the protection of worker rights by employers, and in reaffirming the responsibility and role of both the government and private sector actors in securing these protections. They have created new benchmarks for labor practices across the Gulf, particularly in the areas of recruitment fees, passport confiscation, and independent monitoring.

However, our most recent research shows that additional measures are needed. Penalties and fines should be imposed on contractors found to have violated workers’ rights in order to deter future abuses. It is also necessary to establish an enforceable mechanism, such as contractual guarantee, through which NYU, the Louvre and the Guggenheim can hold the EAA and TDIC responsible if they fail to uphold their promises. The Louvre in particular must make existing promises regarding the protection of worker rights public, both to affirm their commitment to the protection of workers on their projects and to serve as an important precedent for best practices in private sector development projects in the UAE.

In addition, TDIC, the EAA and their international partners should clearly define remedies for workers whose rights are violated and specifically promise to reimburse workers found to have paid recruiting fees. While TDIC’s and EAA’s requirements for contractors with respect to worker rights, including the requirement to reimburse workers for recruiting fees, are admirable, workers are not a direct party to these agreements and do not have clear standing to seek their enforcement via the companies and institutions themselves. Ultimately, even if TDIC or EAA terminate an abusive contractor who has failed to reimburse workers for recruiting fees, there is no assurance that the worker will be compensated. For impoverished workers who cannot change jobs, depend upon their monthly wages to support families and pay debts back home, and who have no source of support or shelter should they quit their jobs with abusive employers, taking matters to the courts presents a heavy burden that discourages workers in all but the most dire circumstances. In light of the limited legal protections and access to justice in the UAE, these agencies need to guarantee that, at a minimum, workers on their sites will not serve as effective indentured servants, stuck in their jobs due to debts incurred by the imposition of unlawful recruiting fees.

While the workers we spoke to continued to report a range of problems in employment, we focus in this report on four ongoing problem areas: 1) recruitment fees, 2) contract substitution, 3) passport confiscation, and 4) the need for effective monitoring and remedies. We address some of the remaining problems reported by Saadiyat workers at the time of our research, including access to medical care, health and safety concerns, accommodation, wage deductions, and payment issues, in our letter to responsible companies and institutions, attached in an appendix to this report.

III. Key Issues

Recruitment Fees

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly documented how workers’ indebtedness for recruitment fees remains a key factor in their exploitation and abuse across the Gulf region. Until workers pay back debts incurred through these recruitment fees, they are effectively trapped in their jobs—including jobs that they did not agree to, or where employers abuse their rights.[10] Strict limits on the right of migrant workers to change employers in the UAE, employer confiscation of worker passports, and employer control over worker visas in the country have trapped workers even with abusive employers, in conditions that often amount to forced labor.[11]

UAE law explicitly prohibits recruitment agents from charging workers any fees associated with their recruitment or travel costs. [12] On January 15, 2011, the UAE government passed a new law to address one aspect of the recruiting fee problem by introducing regulations intended to curb recruiting agents who charge recruiting fees and induce workers with false contracts. The new regulations explicitly prohibit UAE recruitment agencies from charging workers or intermediaries recruitment fees. If a worker is found to have paid a fee to anyone associated with an Emirati recruitment agency either inside or outside the UAE, the Labor Ministry may compel the agency to reimburse the worker. The regulations also hold a recruitment agency partly liable if the employer with whom the agency places workers does not pay the workers. Furthermore, the regulations ban recruiters from placing workers with companies involved in collective labor disputes. While the regulations require UAE recruiters to put down a 300,000 dirham (US$81,000) minimum deposit, which should be available to pay workers' salaries if the company fails to do so, there is no provision to reimburse recruiting fees. However, the regulations do require agencies to pay 2,000 dirhams (US$540) per worker for insurance and allow the Ministry of Labor to revoke or suspend an agency’s license in the event that an agency violates any of the regulation’s provisions.

In March 2011 the Tourism Development and Investment Company of Abu Dhabi ( TDIC) amended its Employment Practices Policy to require that contractors reimburse workers found to have paid any recruitment costs or fees associated with their employment on Saadiyat Island, matching a pledge by New York University (NYU) and Abu Dhabi’s Executive Affairs Authority ( EAA). However, none of the institutions have specified any mechanisms through which workers can register complaints and seek remedy for employers’ failure to reimburse them. Without any such provisions, workers have little recourse should employers ignore the pledge that TDIC and EAA have made. There is also a lack of transparency regarding how many, if any, workers have ever received reimbursement.

During our research in October/November 2010 and January 2011, workers on Saadiyat Island told us they continued to pay high recruitment fees, despite promises by the institutions to address this problem. Almost all of the workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported paying between US$900 and $3,350 to agents in their home countries when seeking employment in the UAE, including some who had arrived recently and worked only on TDIC projects on Saadiyat Island (meaning that the fees were charged in contravention of TDIC’s 2009 pledge). They said they continued to take loans at high interest rates, to mortgage family property, and to exhaust hard-won savings to raise the funds to pay recruitment fees, for the promise of better employment in the UAE.

For example, Kabir A., a 32-year-old worker from Bangladesh, said that he had mortgaged his family’s farm land to pay a recruitment fee of 200,000 Bangladeshi taka (US$2,682), and that after two years of working in the UAE, he still had not paid off his loan.[13] “We [all] bring loans from our side,” he said. “If we can do this job for six years continuously, we can make some money. Three years is not enough.”[14]

Ali R., a worker from Bangladesh who worked for Leighton al-Habtoor, told Human Rights Watch that he had paid 190,000 Bangladeshi taka (US$2,668) to a recruitment agent in his country seven months earlier.[15] Jamshid S., an al-Jaber employee from Punjab, India, said that he had paid 45,000 Indian rupees (US$990) in recruitment fees eight months earlier.[16]

Human Rights Watch notes that many of the workers on the NYU construction site whom we interviewed reported that while they paid fees to obtain jobs in the UAE, they had not paid recruitment fees to obtain their most recent employment contract to work on the NYU site. Many of these workers said they had paid fees to recruitment agencies in their home countries more than five years before. However, some newer arrivals reported that they had paid fees more recently. Shahin M., a worker from Bangladesh, said he had paid 175,000 Bangladeshi taka (US$ 2,347) to come to the UAE 28 months before, and was still employed on his initial contract.

Ensuring that workers do not pay recruitment fees themselves will require employers to proactively seek out and engage in methods of responsible recruiting—methods which are not currently the industry standard in the UAE. TDIC’s employment policy states that contractors may not charge TDIC additional amounts for bringing their practices into compliance—meaning that all contractors hired to date will have to absorb the added costs of complying with TDIC’s March 2011 commitment to reimburse workers for their recruitment fees until they take steps to ensure that workers stop paying such fees.[17] To successfully implement these policies and ensure that contractors pay all workers’ recruiting fees (a major break with past recruitment practices), both TDIC and NYU/EAA should not only levy effective penalties against those who violate the updated policy, but also explicitly commit to reimbursing recruitment fees that workers are found to have paid when contractors fail to do so. As a failsafe—given how significant recruitment fees are to the exploitation and abuse of workers—NYU, the Guggenheim, and AFM/the Louvre should directly reimburse any outstanding fees to workers on their respective sites whenever TDIC or the EAA fails to fulfill this obligation. These institutions, having received considerable financial inducements from the UAE in exchange for their branches, are in a much better position to accept this financial burden than the laborers building their institutions for meager salaries. If these institutions are genuine about preventing labor abuses at their sites, they need to go beyond pledges and demonstrate their commitments by financially guaranteeing that, as a last resort, they will reimburse any laborer on their site who has paid recruitment fees and not been reimbursed, despite pledges by contractors and developers to pay these fees.

Recommendations

- Contractors should provide to TDIC and/or EAA, as the case may be, documentation to prove that either they, the subcontractor, the labor supplier, or another affiliated company have paid all the recruitment fees, including visa fees and travel costs, for each worker hired;

- Contractors should obtain, or require recruiting agents to obtain, a formal statement from each worker signed or formally approved in their home country stating that he has not paid any recruiting fees, as well as from the recruiting agency stating that the agency has not charged any fees;

- Contractors should interview each worker currently employed on a project and ask whether he has paid any recruitment fees, visa fees, or travel costs to any labor supply agency, and reimburse them for any such fees or costs found to have been paid;

- TDIC and EAA should monitor compliance by contractors and subcontractors through an independent and transparent process that includes interviews with workers in their native language. They should penalize contractors working with agents or sub-agents who are found to have charged workers recruitment fees, and should terminate relationships with contractors that continue to work with agencies or sub-agencies that charge workers fees. The penalties should be severe enough to act as deterrent rather than a routine cost of business. The Guggenheim, the Louvre/AFM, and NYU should seek regular updates on compliance and insist that their development partners enforce penalties for violations and terminate relationships with repeat violators; and

- TDIC and the EAA should explicitly commit to reimbursing workers for any recruiting fees they are found to have paid when contractors have failed to do so. If TDIC or the EAA also fails to fulfill this obligation, NYU, the Guggenheim and AFM/the Louvre should step in to reimburse any outstanding recruitment fees paid by workers on their respective sites.

Contract Substitution and Misrepresentation

Not only do recruitment agencies demand high recruitment fees in return for jobs in the UAE, they often provide incorrect or inadequate information about what the jobs entail. As a result, workers can end up incurring large debts on the basis of false promises. Workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch had either failed to sign any contract in their home country, relying on verbal promises made by recruiters, or had signed contracts prior to their departures that did not match the employment or salaries they found upon arrival. When they learned the truth, they had already paid fees and migrated thousands of miles from home, leaving them to choose between forfeiting their investment and returning home, or accepting the terms they found and staying in a job they might never have accepted had they been given a true picture of the terms and conditions of employment.

TDIC’s employment policy states that “New employee’s [sic] shall receive, in their own language, and acknowledge receipt of official confirmation of his terms of employment, including but not limited to all wage information before leaving his country of origin, or where the Employee is already in the UAE, before the Employee is assigned to the Site.”[18] NYU/EAA pledges on workers’ rights remain silent on the issue of workers’ contracts.

Human Rights Watch’s research shows that UAE authorities, contractors, and developers have made little effort to ensure that workers obtain accurate pre-departure information in the recruitment process, and remedies for workers whom agents cheat or deceive regarding their employment. Contract substitution, deception, or misinformation about the nature or terms of employment, and workers’ lack of effective remedies when they find that their employment does not match contracts or promises made back home, remain major problems on Saadiyat Island.

Mizan R. from Bangladesh had worked for 16 months as an “electrical helper” in the UAE. He said that he had paid 200,000 Bangladeshi taka (US$ 2,677) to an agent in Dhaka, to obtain his job. He told Human Rights Watch:

[In Bangladesh,] I didn’t sign a contract—the agency signed for me. They told me my salary would be 900 dirhams [US$ 245] for basic salary. But I get only 600 dirhams [163.40] basic salary.[19] I pay for my own food; I spend about 250 dirhams [US$ 68/per month.] When I came to camp, they brought a paper and told me to sign. I saw only the salary. It was written in English, and I had no time to read it. I didn’t have any experience here [in the UAE], so I didn’t say anything [to them]. I talked to the agency [in Bangladesh] on a mobile [to complain about the salary difference]. They said, “later you will make more money.”[20]

Workers also reported that contract-signing practices in Abu Dhabi remained flawed. Those interviewed described a range of contract practices. Some workers, including two workers Human Rights Watch met at the Guggenheim construction site, said employers had required them to sign a blank piece of paper. [21] Others said that they had been required to “quick-sign”—that employers had presented them with paperwork for immediate signature, giving them no time to examine the documents. [22] Many workers reported receiving contracts in English and Arabic with no translation or explanation in a language they could understand.

Even workers who received wages substantially lower than they had been promised, or told Human Rights Watch that they never would have accepted their employment offers had they known the real josb they would have to do, or the real terms of employment, had little recourse.

Shahin M. told Human Rights Watch that he had worked in the UAE for 28 months, and was still on his initial contract. He said:

In Bangladesh, I was a carpenter. I would make beds [and] cupboards; I rented a shop. It’s good in Bangladesh, but I wanted to get the chance [to do something better]. I thought it would be good and fun in the UAE, and the salary would be going [to help people at] home. I thought, if I go to the UAE I’ll collect some money, do something in my country. A lot of people had successes. Some of my neighbors told me to go to an agent. I paid the agent 1 lakh 75 thousand taka [US$2,347]. I saved some money, but a lot I took from a mortgage on my land….2.5 kani of farming land. I signed a contract in English. The agent said, “it’s carpenter work, [you will be] making 25,000 taka a month [about 1200 dirhams, or US$327].’ When I came, I saw that the salary was only 520 dirhams [US$142].[23]

In a letter to Human Rights Watch responding to our findings, TDIC did not specifically address the problem of contract substitution or the deception of workers prior to their departure from their home countries, even though such practices would appear to be contrary to the spirit of TDIC’s employment policy regarding the signing of contracts that serve as “confirmation of the terms of [each worker’s] employment.” The TDIC also failed to address the shortcomings of contract-signing procedures upon arrival identified by Human Rights Watch.

The Guggenheim also failed to adequately address problems of contract substitution and worker deception. Their response cited a TDIC auditing report that found that, out of 895 workers interviewed, “100 percent of the workers interviewed were holding their employment contracts. In all cases the actual conditions were found to be consistent with what was described in their agreements.”[24] However, these findings did not indicate whether workers had received accurate employment contracts prior to migration; by the time workers arrive in the UAE, having paid significant fees to migrate and with little ability to seek new employment, they effectively have little choice but to sign any contract employers provide them with in the UAE.

Despite remaining silent on this issue in their original promises, NYU acknowledged the need to ensure workers received full information about their employment prior to signing contracts. Their response to Human Rights Watch stated that “contracts should always be available in English and Arabic (as required by UAE law) and, in addition, there should be translators available to assist prior to a contract being signed. We are working with contractors to ensure this is the case moving forward.”[25]

The Louvre/AFM did not significantly address this issue in their response to us.

Recommendations

- TDIC and EAA should require all contractors and subcontractors to obtain copies of contracts signed by workers in their home countries, in their native languages, attesting to the terms of their employment. If workers have already held jobs in the UAE and are recruited in-country, contractors should provide signed and notarized undertakings in workers’ native languages that clearly state the terms and conditions of their employment;

- TDIC and EAA should monitor compliance by contractors and subcontractors through an independent and transparent process that includes interviews with workers in their native languages;

- TDIC and EAA should penalize contractors that continue to work with agencies or sub-agencies that fail to provide workers with adequate information or mislead workers regarding conditions of employment. If the problems continue with one or more contractors, the relationships with them should be terminated; and

- The Guggenheim, the Louvre/AFM, and NYU should seek regular updates on compliance and insist that their development partners enforce penalties for violations and terminate relationships with repeat violators.

Confiscation of Passports

Confiscation of workers’ passports by employers remains one of the most stubbornly entrenched practices we found on Saadiyat Island, despite the relative ease of monitoring this practice and the ready solution. Not only does Emirati jurisprudence prohibit employers from confiscating workers’ passports and other identification documents, but both TDIC’s employment policy and NYU/EAA’s labor commitments clearly state that workers shall retain possession of their personal documents.[26]

Allowing workers to retain physical possession of their passports means that contractors will need to change a decades-old practice that has remained standard, particularly for low-wage workers. To change this practice, developers and foreign cultural and academic institutions on Saadiyat Island must send strong and consistent messages to contractors that confiscation of passports will no longer be tolerated, and that they must depart from past norms. Such messaging includes effective inspection, and levying penalties against contractors who continue to retain documents.

Employers justify confiscation of workers’ passports in a variety of ways. For example employers say that they retain workers’ passports in order to protect their own financial investment in the worker, the time spent training them, etc. Or they sometimes assert that they retain the documents for safekeeping, saying that workers have no safe place in which to store passports. Some employers say that workers themselves prefer to have employers store their passports.

In reality, the confiscation of passports allows employers to keep workers from leaving their employment. The UAE sponsorship system, which holds sponsors liable for workers who “illegally” switch employers, also gives employers incentives to control the movement of their workers by confiscating their passports. Confiscation of passports is one of the main factors in creating conditions of forced labor: workers cannot flee the country even if they are abused because they cannot leave the country without possession of this crucial travel document. The International Labour Organization (ILO) has identified confiscation of passports as a key element in identifying situations of forced labor.[27]

International law and a UAE court ruling prohibit confiscation of passports as a violation of the right to freedom of movement. Without their passports, workers remain at the whim of their employers; in some cases workers have reported employers refusing to return their passports to allow them to attend relatives’ weddings or funerals in their home countries.[28] For example, Mansoor S., a landscaping worker on Saadiyat Island who had come from Bangladesh and worked in the UAE for three years, told Human Rights Watch, “I want to return home because of an emergency. My parents are sick. But [my company is] not letting me go.”[29]

At the time of Human Rights Watch research, despite institutional promises, only one of the 47 workers we interviewed had his passport in his possession. This worker, in a group interview with six others from the al-Jaber construction company, said his company was in the process of returning passports to other workers.[30] Other workers reported that while they did not have their passports, they could request them from their company. Workers described a variety of circumstances for passport retrieval. Some, including those employed by al-Futaim Carillion and working on the NYU site, said that they had a piece of paper that would enable e them to retrieve their passport at any time.[31] Others said they could retrieve their passport if needed. However, workers continued to report that companies maintained physical possession of their passports, and that retrieval depended upon company consent. Ali R. told Human Rights Watch, “My company keeps all the [workers]’ passports. I didn’t see my passport since landing [in the] UAE.” Naveen P., a worker for al-Nabouda Company, said, “The day we stepped on UAE land, they took our passports.” Ismail S., another Nabouda worker, said, “I don’t have my passport. I can get it, but there should be some reason.”

Even workers who signed agreements attesting that they had voluntarily handed over their passports seemed to feel they had no choice in the matter, and indicated that they would not ask for their passports unless they anticipated employer consent.[32] Shahid A., a driver employed by al-Futaim Carillion (responsible for building NYU’s campus), said, “there is no choice with the passport.” Muhsin R., another NYU worker, said “Before [when I worked] in Dubai, we were not supposed to take our passports. When we came to Saadiyat, we could take [them back], but the company will ask why.”

NYU responded to our findings by saying that workers’ documents would be returned to them. A March 27 letter to Human Rights Watch said that, “at this point, contractors should not be holding onto worker passports, even if they’re asked to do so,” and “this should be standard operating procedure in the near future.”[33]

In contrast, both TDIC and the Guggenheim responded to our findings regarding passport confiscation by pointing to the results of a study conducted by an outside monitoring firm employed by TDIC, which indicated that passport confiscation was not a problem on the island. According to the Guggenheim, “the report found that 90 percent of the workers interviewed (out of a total of 895 workers interviewed by the auditor) held their passports and the remaining 10 percent had visas in process.” Thus, the TDIC-employed auditor found contractors to be 100% compliant with company policy. TDIC’s letter further states that “11,538 workers have received their passports.” However, TDIC failed to clarify how its auditors reached this result.[34] If based on the “Site Assignment Agreement” that workers must sign before beginning work on any TDIC project, on release forms individual contractors require workers to sign before beginning employment on Saadiyat Island, or on company records or attestation, these results fail to prove that workers indeed have physical possession of their passports. As discussed below in the “Independent Monitoring” section of this report, results achieved by TDIC’s external auditor to date only underline the need for a transparent, independent, and credible monitoring program.

Recommendations

- TDIC and EAA should immediately require all contractors, subcontractors, and labor suppliers to return workers’ passports to their physical possession;

- TDIC and EAA should monitor compliance by contractors and subcontractors through an independent and transparent process that includes verification of where passports are held, such as through interviews with workers in their native languages. They should penalize contractors, subcontractors, or labor suppliers who are found to have confiscated passports, and should terminate relationships with those that continue to do so. The penalties should be severe enough to act as deterrents rather than a routine cost of business. The Guggenheim, the Louvre/AFM, and NYU should seek regular updates on compliance and insist that their development partners enforce penalties for violations and terminate relationships with repeat violators; and should

- Ensure that all workers, including those housed off the island, have access to personal lockboxes in which to store documents including passports.

Independent Monitoring

Human Rights Watch has long recommended that in order to eliminate violations of workers’ rights, the agencies and institutions involved in developing Saadiyat Island should establish a mechanism to monitor and report publicly on labor practices within the operations of their respective branches, as well as those of any subcontractors and their affiliates (including those who provide construction and maintenance services). In the spring of 2011, both EAA and TDIC separately announced that they had appointed independent monitors to audit and report on compliance for their Saadiyat Island projects. The announcements marked a significant breakthrough and set a positive precedent for all future projects in the UAE and elsewhere in the Gulf.

Prior to announcing independent monitoring consultancies in the spring of 2011, the EAA and TDIC had undertaken some limited compliance checks. In 2010 auditors monitored labor conditions on Saadiyat Island, and TDIC and the EAA/NYU shared some of their auditors’ findings, including findings on passport confiscation and recruitment fees, in correspondence with Human Rights Watch (attached as an appendix to this report). With regard to recruitment fees, TDIC states that 15,354 workers had operated on Saadiyat Island as of December 2010, and that 13,696 —more than 90 percent—of these workers had signed TDIC’s Site Assignment Agreement, which declares that they have not paid recruitment fees to work on Saadiyat Island. [35] However, not only does this written agreement provide an ineffective method for monitoring whether workers have in fact paid recruitment fees, given the linguistic difficulties and flawed contract signing procedures workers described to Human Rights Watch, but the Site Assignment Agreement to TDIC’s employment policy (attached as an appendix) specifically states that workers may be denied access to TDIC sites in the event of their failure to comply with its conditions—including the condition that they have not paid recruitment fees. [36] Because workers who refuse to sign can be barred from working on the island, even those who have paid fees, or who do not have their passports (another condition required), they are unlikely to refuse signing. Auditing results based upon forms signed under possibly coercive circumstances, such as the Site Assignment Agreement, indicate little about the rights workers enjoy in practice. This flawed approach to auditing further confirms the need for a rigorous, independent monitoring program that includes worker interviews and a transparent methodology.

In March 201, NYU and the EAA appointed the UK firm Mott MacDonald to audit and report on compliance with the university's promises for workers involved in the construction of the NYU Saadiyat Island campus. Importantly, the university said that the resulting report would be made public, which it anticipated would happen by the end of 2011. To date, neither party has disclosed information about the terms of reference with the appointed monitor, the nature of monitoring methodology, or the measures to be taken if violations are found.[37]

In May 2011, TDIC appointed Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC), an international auditing firm, to monitor working conditions on its projects. TDIC's announcement said that PwC will monitor and report publicly on whether workers' conditions meet the standards set forth in TDIC's employment policy and UAE labor law (but not additional standards consistent with international human rights law), including requirements that contractors pay workers' recruiting fees, provide health insurance, make on-time monthly wage payments into individual bank accounts, and allow workers to retain personal documents including passports.

Unlike the EAA, TDIC offered specific promises about the methodology that their appointed monitor would use, including random spot-checks and unsupervised worker interviews in workers’ own languages, as well as promising to publish "comprehensive" findings in annual public reports. This welcome level of transparency by TDIC did not extend to other elements raised by Human Rights Watch. To date, TDIC has not released the terms of reference it had established with PwC, a full description of the planned methodology and scope of monitoring, or any requirements or restrictions the monitor would adhere to in producing public reports. The absence of this information makes it difficult to assess whether the contract provides for fully independent monitoring (as opposed to an internal compliance program). For example it is not clear whether or not mechanisms are in place to ensure that: the monitor can operate with sufficient autonomy; conflicts of interest are avoided; pertinent issues will be examined; an appropriate methodology will be utilized; and a clear reporting system is in place that allows publication of monitoring results without interference or censorship from the hiring party.

On September 14, 2011, Human Rights Watch sent a letter to the institutions and development partners requesting additional information on their monitoring programs, including terms of reference, scope of monitoring, and research methodologies. We received no additional information from TDIC, the EAA, or any of the institutions involved. An email from TDIC on October 19 responding to our request noted that the questions “raised in your letter will be addressed in the annual public independent monitoring report and according to international best practices.” In response to subsequent emails, TDIC said it did not have a release date yet for the monitoring report.

Once the independent monitors’ reports are available, and assuming they include at least basic data on the number of violators identified and the action taken in response, this information will provide a useful tool for assessing the seriousness of the effort to address worker conditions. In earlier discussions, Human Rights Watch has strongly encouraged TDIC and EAA to identify and punish contractors and subcontractors who fail to adhere to standards on workers’ rights. In our February 2011 letter, Human Rights Watch asked TDIC and EAA questions including:

1) How many contractors or agents have been reported to your institution as violating the terms of your labor values policy?

2) What measures has your institution taken or recommended to penalize violating contractors?

3) How many recruitment agents have been reported to UAE authorities for violating UAE laws and charging workers on your project(s) recruitment fees? Have you identified any recruitment companies ineligible to provide workers for your projects?

In its March 2011 reply, TDIC said it has “always worked with an independent monitoring consultant, who provides regular reports on contractors’ performance.” It stated that “48 audits have been carried out on contractors operating on Saadiyat Island,” out of the “130 companies, including sub-contractors and labor supplies, [that had] operated on Saadiyat Island” as of December 2010. TDIC stated that penalties for non-compliance ranged from warning notices to contract termination, without specifying how many warning notices it had issued to contractors or how many contracts had been terminated.

The EAA, in its reply to Human Rights Watch, stated that its policy framework and implementation protocols include “a rigorous and ongoing internal compliance process, structured to identify one-off problems and systemic issues, which are subsequently addressed through the enforcement regime,” and that its enforcement regime is “designed to support the fulfillment of the Statement of Shared Labour Values”. However, the EAA did not elaborate further.

Looking ahead, one issue remaining to be addressed is whether and by what means institutions will act should TDIC or the EAA fail in their promise to enforce protections promised in the TDIC’s employment policy or in the Statement of Shared Values issued by NYU and EAA. According to these two documents, the commitments they contain are incorporated into contracts between TDIC or EAA and companies awarded contracts on the island, which provide means by which the contractors can be held responsible for upholding the standards. The cultural institutions involved in Saadiyat Island projects also describe them as shared commitments and should ensure that they, too, have a means to enforce the commitments they have secured from their development partners. In the event that developers fail to enforce their policy with contractors, these institutions should be sure that they have recourse through a contractual provision or other means to hold their respective developer accountable.

In a May 11 meeting between Human Rights Watch and representatives of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Culture regarding the Louvre Abu Dhabi project, advisor Christine Gavini-Chevet stated that “If violations of social rights are huge [and] serious, then there will be no way to continue working with our Emirati partner.”[38] She added that, “We cannot cancel some parts of the contract … it is either all or nothing.”[39]

Recommendations

· TDIC and the EAA should release comprehensive information about the terms of reference and methodology of the monitoring firms they have engaged, to demonstrate their respective firms’ independence in auditing and reporting;

· They should also publish the results of the monitoring programs for their respective sites, as they have committed to do, and ensure that the reporting is comprehensive; and

· TDIC and the EAA should set publicly-announced penalties for contractors who violate standards and put into effect clearly-defined remedies for workers whose rights are violated, including a direct promise to reimburse workers found to have paid recruiting fees if the developer fails to do so.

Case Study: Nurredin A., from Punjab Province, PakistanNurredin A. is married, with two children. He works for a labor supply company supplying workers to Leighton al-Habtoor. Human Rights Watch met him on the Guggenheim construction site, where he was working to construct the pilings (sub-foundation) for the new museum. He lived at a labor camp in the Musaffa Industrial Area of Abu Dhabi, a large industrial neighborhood outside the city where thousands of workers are housed.[40] I have been in Abu Dhabi for 14 months. I paid 150,000 Pakistani rupees [US$1,747 in recruitment fees to an agent] for a visa back home. At home, my agent said I would make 700 dirhams [US$191] in basic salary. The agent told me I would work in a processing plant, packaging bottled water, but when I arrived, I was made to sign a new contract, to work as a construction worker, at a lower salary of 525 dirhams [US$143]. [But] I have no experience building. I worked as a driver in Pakistan. I didn’t complain [about the salary or the job] to the company because it won’t help to complain. Some of other people in my room are working for the same company. Nobody is happy. [Now,] I earn the 525 dirhams [US$143] basic salary, plus overtime, as a crane helper. I am helping with the pilings and with the drilling machine. My job is to make the land strong. Sometimes I am making 720, 725 dirhams [US$195] per month, including my overtime pay. It’s a very difficult job, long hours [and] hard work. In the morning, we start [from the labor camp] at 6 a.m., and start work at seven. We get a half-hour break, and return back here at 8 pm. There is no arrangement for cold water; we have to come to the central area. The boss will ask us, “why are you going to the water so many times?”, so we can’t go too often. Sometimes I have a headache, fever. It’s not that serious—I never went to the clinic. I think I was sick because of tiredness, and the heat. [Soon after I started my job] we had a safety briefing—it was a one hour meeting. After that, they said, “you have to do this work, starting tomorrow.” During the safety training, they said to wear a helmet, have safety shoes, don’t throw trash everywhere. My company pays a food allowance of 125 dirhams [US$34]. But we need a minimum of 200 dirhams [US$54] for even simple food. Because of inflation, even 300 [US$81] might not be enough for good food. We just eat dal, vegetables. We cannot eat meat, just two or three times per month. There are two kitchens for the whole company, [about] 50 or 60 employees. Our accommodation looks good, but we are living [in rooms with] between 14 and 16 people per room. I still haven’t been able to make back the 150,000 rupees [US$1,747] I paid for my visa. That was my money that I earned [and saved]. I send 6,000 Pakistani rupees [US$ 70] each month for my family, maybe 7,000 [US$ 82]. Most of the people who work for my company have the same problems. If I knew that I had to do this work, I would never have come here for this. |

Appendix: Related Correspondence

Letter from Human Rights Watch to Main Parties Involved in the Saadiyat Island Development Project – February 24, 2011

February 24, 2011

To: The Abu Dhabi Tourism and Development Investment Company (TDIC); the Abu Dhabi Executive Affairs Authority (EAA); New York University; the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation; and Agence France Museums

Following up on our last meetings with several of you, we wish to inform you about our ongoing efforts to monitor the progress of labor rights protections for migrant workers employed on Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi.

Recently, many of your institutions made public commitments to uphold a variety of workers’ rights protections, including provisions relating to payment of recruitment fees, workers’ freedom of movement, protections against forced labor, health and safety provisions, minimum standards of accommodation, electronic monitoring of wage payments, and the provision of adequate rest and leisure. We note, however, that Agence France Museums/the Louvre has failed to publicly announce commitments on workers’ rights to date.

In October and November 2010 and again in January 2011, Human Rights Watch visited Saadiyat Island and interviewed, in individual and group settings, migrant workers engaged in construction projects on the island. We met interviewees on worksites that included the Saadiyat Island Cultural District and the NYU and Guggenheim construction sites, which were clearly signposted with their respective names. Interviews took place at work sites and at off-site labor camps. Workers provided the names of their employers, which we saw printed on many workers’ uniforms and pay slips, as well as posted at work sites. Employers included Leighton al-Habtoor, al-Jaber, Saif bin Darwish, al-Nabouda, al-Hilal, al-Futaim Carillion, Dulsco, and al-Ryum Companies.[41]

We conducted this research to update the findings of our 2009 report, The Island of Happiness: Exploitation of Migrant Workers on Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi, particularly with the knowledge that there remained lack of clarity regarding your commitment to provide independent, third-party monitoring of labor conditions for workers on your projects. We plan to issue a new report based upon our findings. In this letter, we share with you these findings prior to publication, in order to give you an opportunity to respond. We will incorporate responses received within one month from the date of this letter’s issuance into our public reporting. Some of you have already responded through private conversations, and while we have not reflected those updates in this private correspondence, we will follow up with you to ensure that your responses appear in our published material.

While our research indicates that there have been some improvements in problems we have previously documented, particularly in the regular payment of wages into personal bank accounts, it appears that employment practices still fail to conform to the various commitments made by your institutions, such as TDIC’s Employment Practices Policy (“TDIC EPP”), dated June 2010, the TDIC/Guggenheim Statement of Shared Values (“Guggenheim Statement”), published September 22, 2010, the SA8000 standard, adopted by Agence France Museums and TDIC for their Louvre Abu Dhabi project, though not publicly announced, on March 6, 2007 (“Louvre Standards”), and NYU/EAA’s Statement of Labor Values, as well as the Additional Information on the Construction and Operation of NYU Abu Dhabi(together, the “NYU/EAA Statement”) dated February 3, 2010. In some of the cases we researched, it additionally appears that ongoing practices on the island violate UAE law as well as international standards for labor rights and migrant workers’ rights.

In summary, workers nearly universally reported that they had paid high recruitment fees to obtain their jobs in the UAE. In some cases, workers said they had paid these fees over three years ago, while in other cases, they had paid fees just a few months before arriving in Abu Dhabi, to obtain their most recent employment contract. Some workers said that they had not signed an employment contract before leaving their home country, while others reported that, in cases where they had signed a contract in their home country, employers required them to sign new contracts with different terms upon arrival in the UAE. Some workers reported that the nature of their employment was substantially different from what agents had promised in their home country.

In a positive development, almost all workers interviewed said that they received timely electronic payments for both their regular wages and overtime pay into personal bank accounts. Most workers said they received regular rest breaks and days off and reported that employers observed summertime restrictions on afternoon work. However, it appears that contractors are not uniformly applying these improvements.

Some workers complained that employers deducted significant portions (up to 25 percent) of their monthly wage as a “food allowance.” Many of the workers interviewed said that they did not live in the TDIC Workers’ Village, and some cited problems with their accommodations. All but one of the workers interviewed held employer-paid health insurance, and all said they had received safety clothing and training, though some felt their training had not been adequate and felt ill-equipped for their jobs. Finally, of all the workers interviewed, only one had possession of his passport.

1. Recruitment Fees

As long documented by Human Rights Watch, one of the leading factors in worker exploitation and abuse in the UAE is their indebtedness for exorbitant recruitment fees, which effectively traps workers in unsatisfactory employment. It appears that workers on Saadiyat Island continue to pay these fees, without remedy by your institutions, despite promises to address this problem.

Under UAE labor law, the employer must pay all recruitment fees associated with hiring migrant labor.[42] Your institutions have addressed this issue in your public commitments to protect workers’ rights on Saadiyat Island, but thus far not with the specificity needed to avoid the payment of such fees by workers. The TDIC EPP prohibits contractors from working with agents that charge workers such fees and further stipulates that contractors remain solely liable for all costs and fees associated with workers’ employment on Saadiyat Island.[43] However, the TDIC EPP includes no mechanism to reimburse workers found to have paid such illegal fees. The Guggenheim Statement stresses its commitment to preventing employees involved in constructing its Abu Dhabi site from paying these fees, stating “ No one involved in the construction of TDIC’s projects shall utilise the service of any agent or agency charging an employee any recruitment fee.”[44] But it too includes no mechanism for enforcement of this provision or reimbursement for workers found to have paid such fees. The Louvre Standards do not address recruitment fees specifically, but prohibits forced labor using international legal standards, including ILO conventions on forced labor.[45] ILO research on forced labor has found recruitment fees to be one of the main factors contributing to situations of forced labor and debt bondage.[46]

The NYU/EAA Statement, the most robust of these commitments, includes the provision that “ Employers will fully cover or reimburse employees for fees associated with the recruitment process, including those relating to visas, medical examinations and the use of recruitment agencies, without deductions being imposed on their remuneration.”[47]

Despite your institutional commitments to date, almost all of the workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported paying between US$900 and $3,000 to agents in their home countries when seeking employment in the UAE, including some who had arrived recently to work specifically on TDIC projects on Saadiyat Island. They said they continued to take loans at high interest rates, mortgage family property, and to exhaust hard-won savings to raise the funds to pay recruitment fees, for the promise of better employment in the UAE. Ali R., a worker from Bangladesh who worked for Leighton al-Habtoor, told Human Rights Watch that he had paid 190,000 Bangladeshi taka (US$2,668) to a recruitment agent in his country seven months earlier.[48] Jamshid S., an al-Jaber construction company employee from Punjab, India, said that he had paid 45,000 Indian rupees (US$990) in recruitment fees eight months earlier.

Human Rights Watch notes that nearly all of the workers on the NYU construction site, employed by al-Futaim Carillion, whom we interviewed reported that they had not paid recruitment fees to obtain their most recent employment contract; instead, the majority of these workers had paid fees over five years before, they said. However, one al-Futaim Carillion worker at the NYU site said that he had arrived just over a year ago and had paid for his plane ticket. Another on the site said that he had arrived 28 months before, and paid 175,000 Bangladeshi taka (US$2458) in recruitment fees.

In contrast, the prevalence of recently paid recruitment fees by workers employed on other work sites, including throughout the Cultural District, indicates that TDIC and the Guggenheim have failed to give meaning to assurances that only employers will pay recruitment fees. The only meaningful remedy to this practice will be a policy of interviewing each worker currently employed on a project and asking whether he has paid any recruitment fees, visa fees, or travel costs to any labor supply agency and reimbursing them for any such fees or costs. Furthermore, TDIC, the Guggenheim, and NYU/EAA should implement their promise to insist that contractors stop working with agents that have charged workers such fees, and report these agents to the relevant embassies or consulates. Agence France Museums (AFM)/the Louvre should immediately commit to ensuring that contractors involved in the Louvre Abu Dhabi project pay workers’ recruitment fees, and to penalizing contractors who worked with agents that charged workers fees.

On the subject of recruitment fees, Human Rights Watch respectfully requests replies to the following questions:

- What steps has your institution taken to monitor whether workers employed on your projects have paid recruitment fees to obtain employment?

- Have you asked each contractor to attest that it has paid all of the recruitment fees for each of its employees, and that it has ascertained that none of its employees have otherwise paid fees?

- How many contractors or agents have been reported to your institution as violating the terms of your labor values policy?

- What measures has your institution taken or recommended to penalize violating contractors?

- How many recruitment agents have been reported to UAE authorities for violating UAE laws and charging workers on your project(s) recruitment fees? Have you identified any recruitment companies ineligible to provide workers for your projects?

2. Contract Substitution and Human Trafficking

As previously documented by Human Rights Watch, “contract substitution,” and other practices involving the promise of jobs and wages in the home country markedly superior to a worker’s actual assignment once in the UAE, have been a widespread problem for migrant workers. Our research indicates that these practices continue to be a problem despite your public institutional commitments to ensure that the terms workers are promised in their home country are the terms they actually get once in the UAE.

TDIC’s EPP states that “New employee’s [sic] shall receive, in their own language, and acknowledge receipt of official confirmation of his terms of employment, including but not limited to all wage information before leaving his country of origin, or where the Employee is already in the UAE, before the Employee is assigned to the Site.”[49] The Guggenheim Statement reiterates these commitments.[50] However, the NYU/EAA Statement remains silent on contracting requirements, and the Louvre Standards also fail to contemplate this aspect of migrant labor contracting.

Many of the workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch in November 2010 said that their wages on Saadiyat Island were less than the amount they had been promised in their home countries. In some cases, they said that they had to work different jobs than what they had contracted for with recruitment agents in their home countries. However their lack of access to their passports, recruitment debts, and the urgent need to send income home to their families, combined with workers’ inability to change jobs, left them trapped in whatever employment conditions they found upon their arrival in the UAE.

Some workers reported that agents in their home countries had required them to sign blank pieces of paper before departure. Others said they had signed one contract in their home country, in their native language, and another upon arrival, in Arabic or English (languages that many of them did not read). In cases where agents in workers’ home countries provided employment contracts in their native languages, these contracts did not match the conditions workers later found on Saadiyat Island, they said.