Introduction

In the charred remains of Mariupol, a vibrant city once stood.

Before Russian forces attacked, about 540,000 people called the bustling city in southeastern Ukraine home. It was a place as rich in culture as it was in industry, strategically placed on the Sea of Azov.

When the weather was warm, city residents crowded onto Mariupol’s beaches, wading into the shallow waters to a chorus of seagulls. They strolled through the city’s main garden, enjoying its tulips and playgrounds with a view of the sea. “Let’s meet at the water tower,” friends would say to each other, gathering at the century-old red and white brick tower in the city center.

There were popular festivals celebrating the arts – like Gogolfest, in honor of the nineteenth century novelist and playwright Nikolai Gogol. Ukrainians from all over came to see plays at the Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theater, in the heart of the city, and attend performances at Mariupol’s Chamber Philharmonic next door.

A young girl waves a Ukrainian flag at Ukraine Independence Day celebrations on August 21, 2021. © 2021 aerocaminua / POND5

The Sea of Azov as seen from Mariupol on January 30, 2022. © 2022 Brendan Hoffman/New York Times

Children play in front of the Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theater in May 2021. © 2021 SEBASTIAN BACKHAUS/Agentur Focus/Redux

A playbill for Gogolfest in Mariupol on May 1, 2018. © 2018 Oleksii FILIPPOV/AFP

Artists perform a concert during Gogolfest in Mariupol on May 1, 2018. © 2018 Oleksii FILIPPOV/AFP

Home to two of Ukraine’s largest iron and steel factories, Mariupol invested hundreds of millions of dollars in its roads, public transportation, and parks.1 The sea was both a part of the city’s identity and part of its promise: one of the largest ports in the region allowed Ukraine to export coal, steel, and grain around the world.

On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. For nearly three months, the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation along with affiliated armed groups from the Donbas region of southeastern Ukraine engaged in a fierce battle against the Armed Forces of Ukraine to take Mariupol. Russia saw Mariupol as a strategic prize. Dominating areas to the west of the city would allow the Kremlin to control a land corridor between the Crimean Peninsula and the Donbas region.

By March 2, Russian forces were besieging the city. As Russian and affiliated forces gained ground, attacking with tanks, mortars, heavy artillery and aircraft, families left their homes and followed stairs deep into basements, down into darkness.

In early March, an estimated 450,000 civilians remained stranded in Mariupol, unable or unwilling to leave their homes, loved ones and the lives they had built. The fighting had seriously impaired critical infrastructure, including electricity, running water, heating systems, and telecommunications, bringing the city to its knees.

By April 13, occupying forces had seized control of most of the city, declaring victory on April 21.2 On May 17, Ukrainian forces holding out at the Azovstal steel plant began surrendering. The fate of Mariupol rested in Russian hands and remains so.

War transformed the city into something unrecognizable: a tangled mess of crumpled buildings and a place of shallow graves. Thousands of civilians were killed during the fighting or died from other causes. Mariupol has suffered some of the worst destruction in war-scarred Ukraine.

Human Rights Watch, SITU Research and Truth Hounds collaborated to document the devastation of Mariupol.

Unable to conduct research in Mariupol, we relied on accounts obtained in person or by phone from hundreds of displaced survivors and witnesses; geolocated and verified 850 photographs and videos; analyzed satellite imagery of graves to estimate the death toll; conducted a remote block-by-block assessment of the extensive damage in the city center; and investigated which Russian forces and commanders may be responsible for war crimes.

We focused on the damage around Myru Avenue, the Avenue of Peace, a central artery of the city.

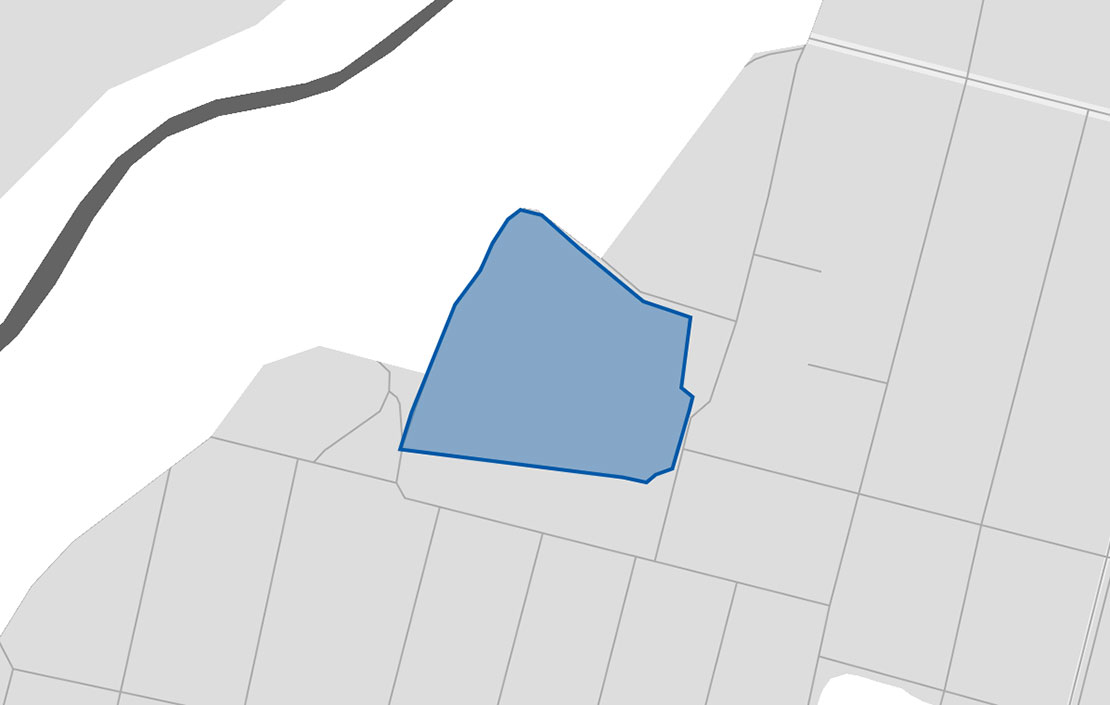

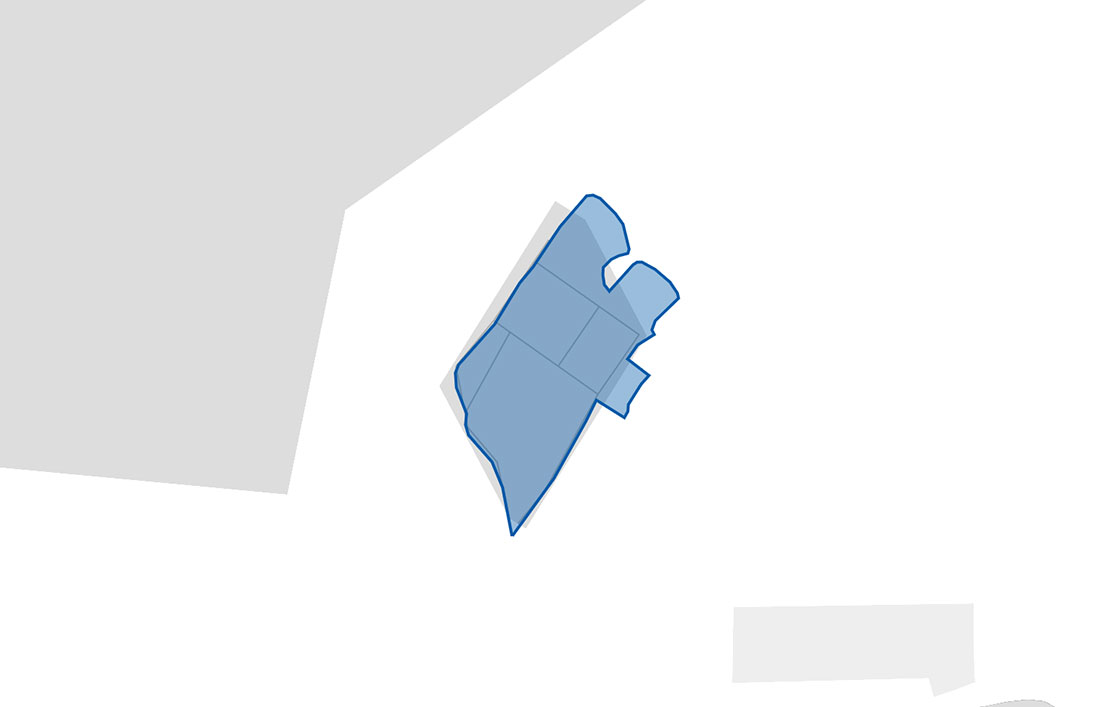

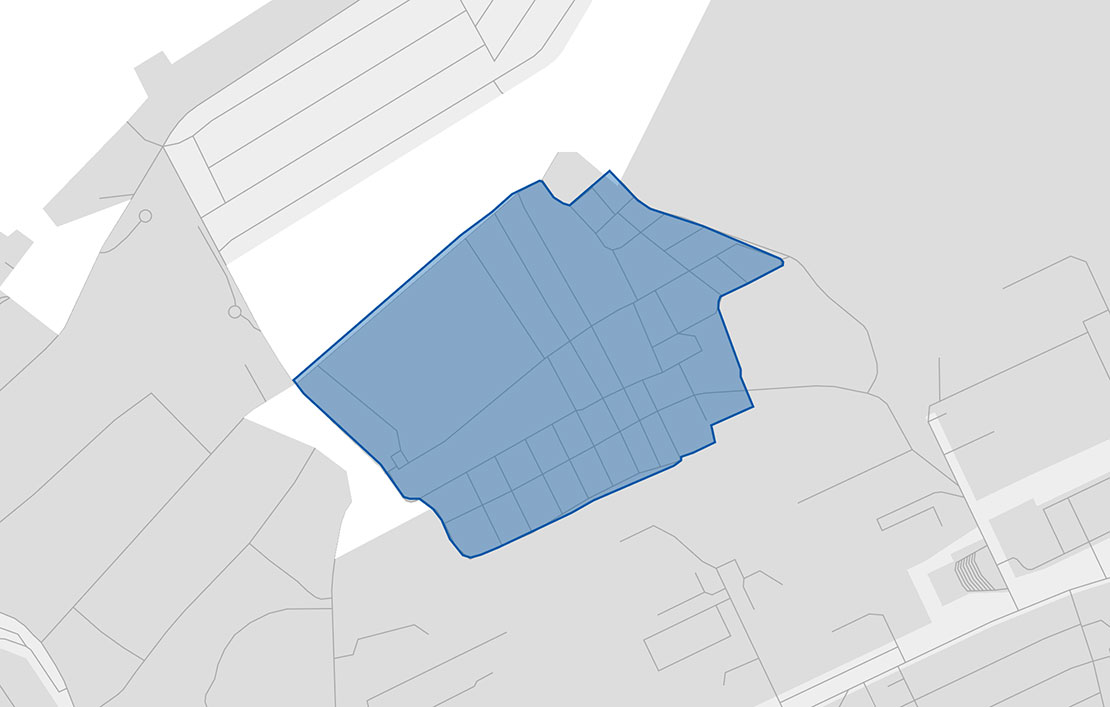

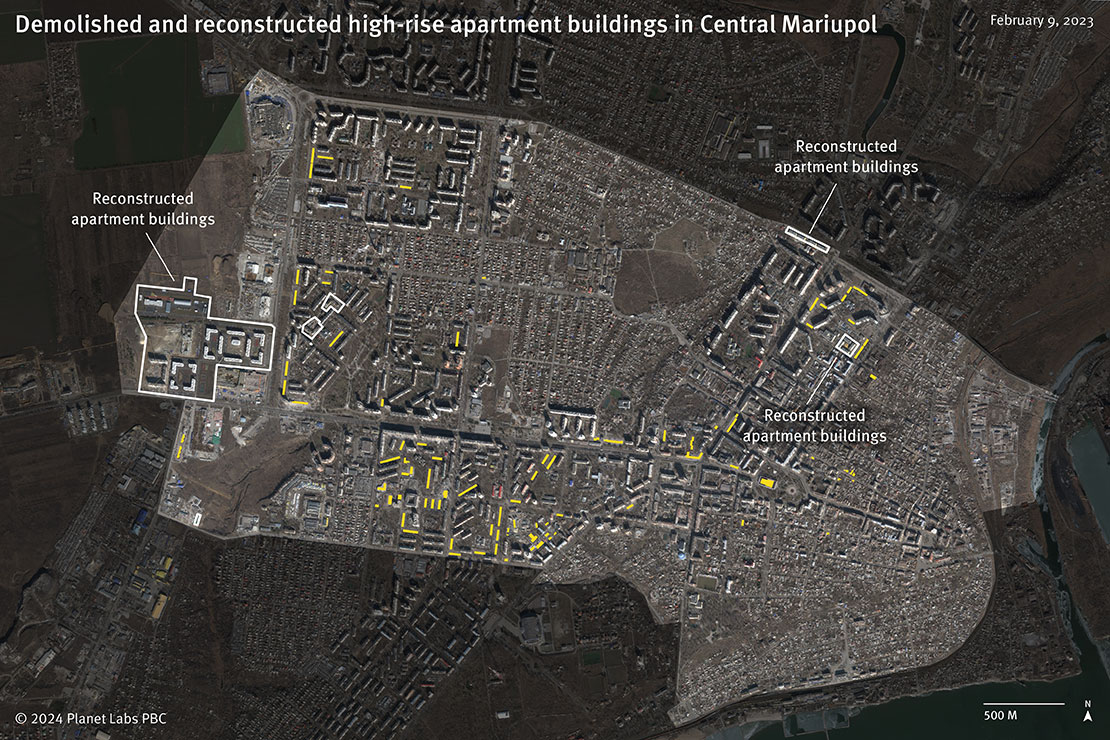

Our investigation included analyzing 4,884 damaged or destroyed buildings in an area measuring roughly 14 square kilometers, a quarter of the city’s urban zone.

Creating 3D models of seven buildings within this area helped illustrate the extent of the damage. Russian occupying forces began tearing down buildings as early as June 2022.3

These seven buildings each represented a different and unique part of life in Mariupol.

One was a residential apartment complex that hundreds of people, spanning generations, called home. Another, a hospital where city residents accessed health care, including for labor and delivery. There was the university where students learned about the world and fostered skills to develop their city. A cozy single-family home in a quiet neighborhood. A building on a busy city street, complete with a bank, a shopping center, and a playground for children. There was the neoclassical building in the center of the city. And an ornate theater, the beating heart of Mariupol, where the community celebrated the arts.

When war came to Mariupol, the identities of those buildings, and the communities they fostered, were stripped away. They became something else: first places of refuge, then, scenes of injury and death.

Two years have passed since Russian forces besieged Mariupol. Much global attention, drawn to other hotspots in the grinding war or to other major conflicts, has moved on. But life has not returned to normal for the city’s residents; the Mariupol they knew is largely gone.

As Russian occupying forces clear away the rubble, building a new city in Russia’s image between mass graves and the Sea of Azov, questions of accountability abound.

Some seek closure and healing. Many are waiting anxiously for the city to be restored to Ukrainian control, for reparations to be paid, and for those responsible for abuses to face justice.

This project aspires to support the push for accountability, through documentation. It also tries to capture some of what was lost so that it is not forgotten.

The Missing

Warplanes flew menacingly over Mytropolytska Street 98 in early March, while

But inside the basement, 3-year-old Arina Antipenko, called “Arishulka” by her grandmother, was playing a game.

“Look Dyma, I am a princess,” the smiling toddler told her 22-year-old neighbor, Dmytro Lastenko, urging him to join in her make-believe.4

Despite the darkness and the dampness, many residents of Mytropolytska Street – a tree-lined street running through downtown Mariupol – hoped they would find safety in basement rooms.

The basement of the large apartment complex seemed like the safest bet. It was one of hundreds of places that local authorities designated as shelters.5

There, Arina and her parents, Ivan and Khrystyna, who lived nearby, huddled in blankets next to other families. Packed tightly on the floor, they prayed for relief from the war raging outside, some filming the experience on their phones.

They exited only briefly through the green front door, into the freezing cold and swirling snow, to find clean water and to cook food on makeshift stoves.6

On March 11, Arina spent the afternoon dancing and playing in the basement.7 Around 3 p.m., Danylo, an entrepreneur, was protectively taping his windows shut in the neighboring building when he heard an aircraft overhead.8 He ran into the corridor for safety, fearing an attack. Then came the explosion, his windows shattering into jagged pieces of sharp glass.

Facts about the attack

- Building: Mytropolytska 98

- Coordinates: 47.107290, 37.514850

- Date: March 11, 2022

- Military forces in the vicinity at the time of attack: Witnesses said there was heavy fighting in the area and they saw Ukrainian forces trying to deploy in the building the day before the attack, but they did not see them there when the attack occurred. While Ukrainian soldiers may have been near or in the building at the time, witnesses also said many civilians were entering and exiting the building on a regular basis in the days before the attack.

- Weapon used: Air-dropped bomb

- Death toll: At least 17 people were killed.

- Dimensions of rubble pile: 25 meters wide, according to the estimates of one man, Pavlo, who was part of a series of teams later tasked with removing rubble – and bodies – from the building.

An air-dropped bomb tore through the middle of Mytropolytska Street 98, a high-rise residential building in the city’s Central District. In our area of focus, 93 percent of high-rise residential buildings were damaged in attacks.

It was the kind of tactic that Russian forces have employed elsewhere in the country, such as in Izium, where they appear to have targeted residential apartment buildings with air-dropped bombs, leading to enormous loss of civilian life.

Throughout the fighting, the highest levels of Russia’s command structures, which included President Vladimir Putin, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, and chief of the general staff, Valery Gerasimov, had detailed knowledge of the situation in Mariupol and were involved in the planning, execution, and coordination of military operations conducted there.

President Putin issued direct orders. Other senior officers in Russia’s General Staff and other forces, including the director of the National Guard of Russia, Viktor Vasilyevich Zolotov, and the then-commander of the Southern Military District, General Alexander Vladimirovich Dvornikov, also had command responsibilities and most likely participated in high-level decision-making.

At Mytropolytska Street 98, five floors collapsed in the central part of the building, crushing people. Concrete walls crumbled, ripping apart wallpapered living rooms and tiled bathrooms.

Entrance number 3, close to where families had cooked outside for days, was gone.9 The result was a heaping pile of destruction some 25 meters wide, according to the estimates of one man, Pavlo, who was part of a series of teams later tasked with removing rubble - and bodies - from the building.10

Survivors trapped inside called out for help, their moans heard by neighbors.11 Fire engulfed part of the building, but the fire brigade, faced with shelling, was forced to turn around.12 One woman leapt to her death from the fifth floor, rather than succumb to the smoke and fire, her granddaughter wrote in an online memorial.13

In the basement, bodies blackened by fire lay on the ground. The room where Arina’s family had spent days and nights sheltering was destroyed. Out front, people’s belongings hung in the trees, the air tinged with the smell of burned flesh.

Survivors emerged from the smoldering basement in a state of shock. With electricity cut and phone lines down, people turned to strangers on the internet in a desperate plea to find their loved ones.

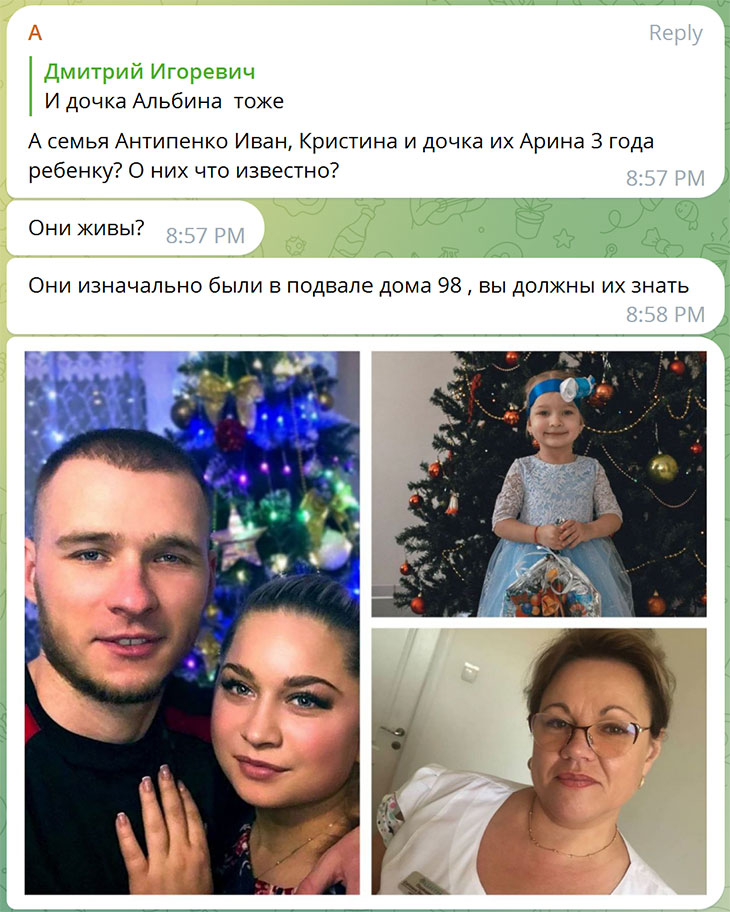

“Are they alive?” read one March 2022 message, asking about Arina and her family. The message was in a neighborhood Telegram group, alongside a series of photographs: Arina smiling in a blue holiday dress, a blue bow in her hair. Her parents embracing in front of a Christmas tree. Ivan’s mother, Svetlana, posing for a photograph.

The Telegram exchange was one of thousands in a flurry of messages from people desperate to find family and friends as news emerged of attack after attack on residential buildings and shelters across the city. Many would be looking for months. Some are still looking.

Nobody seemed to know where the Antipenko family was.

On April 24, 2022, Orthodox Easter Day, a group of men tasked by the Russian occupation administration to remove rubble and bodies from buildings found the body of a child at Mytropolytska Street 98.14 Pavlo, one of the volunteer workers, had chosen not to work at the site that day. He knew they were going to find the child; survivors had told him that Arina and her family never emerged from the rubble.

The child’s remains, one of 17 bodies and body parts found by Pavlo and his team over several weeks in April, was the smallest they had found. She looked between 3 and 5-years-old, he was told, and was found next to bodies that matched the description of the Antipenko family by people who saw them before the attack: a man in dark clothes, a woman in jeans, an older woman in a pink robe. But was it Arina?

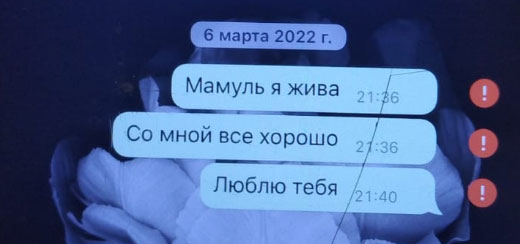

In May, two months after the attack, Dmytro Lastenko, who was in the basement during the attack, returned to the ruins of the building in search of his identity documents. Using a shovel, he dug into the rubble. The smell of death lingered. And with it, lumps of hair, blankets, and a cell phone, its screen cracked. He recognized the phone. It belonged to Arina’s mother, Khrystyna. He brought it to Khrystyna’s mother, Stefaniia, who lived in a different town.

On it were three undelivered messages from March 6, 2022: “Mommy,” it read. “I’m alive. Everything is fine with me. Love you.”

Following the attack, Stefaniia repeatedly tried to enter Mariupol to find her family, but Russian forces denied her entry, she said. Finally, on April 15, she successfully entered the city and began her months-long search.

She walked up and down streets in her daughter’s neighborhood, showing photographs of her missing relatives.

“I went to different basements and shouted the names of my children,” she said. “People were still huddling in basements. It was dark, and I couldn’t see faces, so I shouted.”

Stefaniia returned to the ruins of Mytropolytska Street 98, where blankets and clothing lay strewn under rocks and jagged wire. She recognized some of the items: Ivan and Khrystyna’s marriage document, Khrystyna’s hat, Arina’s birth certificate.

She visited the city’s central makeshift morgue again and again, for months. There, desperate to find her family, she meticulously combed through decomposing piles of the bodies of men, women, and children. Some bodies were wrapped in large black bags, arranged in the yard of the morgue. Others, dug up from the ground, were strewn on blankets. There were other piles, too: mounds of clothing and footwear taken from victims, and wooden coffins ready for the dead.

Stefaniia returned every other day, like clockwork: unclaimed bodies were buried after two or three days. She didn’t want to miss finding her family’s bodies if they arrived at the morgue.

“On one day we would come, the next day we would try to recover after [seeing] the horror,” she said. “Then, again, I would come [back again].”

Finally, in late September, Stefaniia found a photograph of Arina’s body in a computer database of the city’s dead managed by occupation authorities. “She had an earring in the shape of a crown,” she said. “I recognized her by her teeth, by her clothes. I know these clothes.”

Arina was assigned a number in the database: 1734. So Stefaniia went looking in Mariupol’s biggest cemetery, Starokrymske, where she found a grave marked with the number 1734. But next to the grave’s cross was the picture of another little girl. It wasn’t Arina; it was a girl named Eva, who Stefaniia was told had been shot in a car. Eva’s family had mistaken Arina’s body for their own little girl.

That night, Stefaniia dreamed that she heard Arina whimpering from inside the mislabeled grave.

It wasn’t until October 5 that she was finally able to find her granddaughter’s body, which had been dug up from Starokrymske cemetery by Eva’s relatives a week earlier and reburied in Novotroitske cemetery, about 2.5 kilometers northeast of the city’s Left Bank district. With the permission of occupying authorities, she exhumed Arina, who was buried in a black body bag inside of a small coffin, and reburied her in her hometown elsewhere in Ukraine.

She has not found the bodies of Arina’s parents, Khrystyna and Ivan, or Ivan’s mother Svetlana. She will never stop looking, she says.

For now, they remain “missing,” their remains lost among the remains of thousands of other people. On July 19, 2022, Stefaniia provided her own DNA sample to occupation authorities. They told her to wait for DNA test results from bodies that would be compared to DNA samples of surviving relatives, and that the process could take over a year. At the time of writing, she was still waiting.

“I was a mother and a grandmother, and now I’m nobody,” she says. “My [family was] my wealth, my life was joy and happiness, and now there is nothing. I only ask God to find the bodies of my children to bury, to be next to me.”

Struggling to Survive

War forms part of Mariupol’s recent history: its residents endured nearly two years of German military occupation from 1941 to 1943, during which Nazi forces rounded up, killed and deported thousands of people, most of them members of the Jewish community. The grandchildren of those who lived through that time would also live through armed conflict.

For five weeks in the summer of 2014, Russia-backed armed groups and Ukrainian government forces clashed in parts of Mariupol. Since then, Mariupol residents had become accustomed to living close to the front lines, and occasionally hearing fighting in the distance, but they were hopeful, some convinced, that Mariupol was impenetrable. Eight years later, nobody was prepared to see their neighbors die in the street, their loved ones crushed in basements – and the loss of Mariupol to Russia.

“Every street is saturated with blood, pain, horror,” said one former Mariupol resident. “This is a trauma for many, many years…probably for more than one generation.”

It only took a week or two for the city to become unrecognizable. With city blocks turned into front lines, several hundred thousand remaining residents faced the same challenge: how to stay alive.

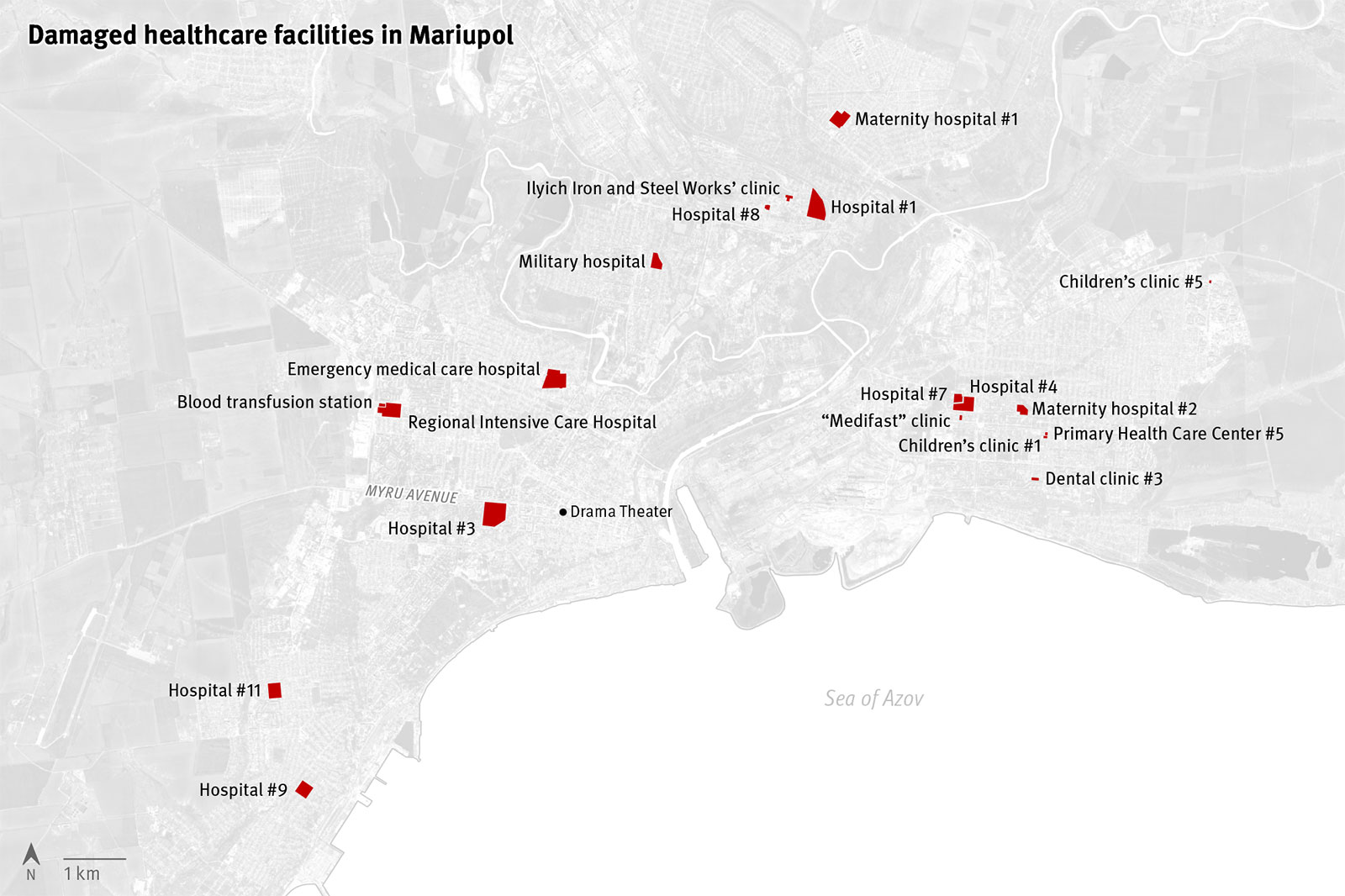

Nearly two and a half kilometers southeast of Mytropolytska Street 98, where hundreds lived and raised families before the war, stood the city’s main hospital for women and children, a yellow and lime green building known as Hospital #3. There, with its brightly colored corridors and sterile examination and surgical rooms, the city’s inhabitants gave birth, sought out gynecological care, and nursed their sick children in the modern facility.15

When Russian forces invaded Mariupol, the assumed safety of the hospital grounds took on new meaning, with dozens of men, women and children making their way to the bunker beneath the hospital complex to the south of the oncology building, accessible by a ramp. Many spent weeks there trying to survive. “It was an old, strong shelter, but it was cold,” said Rustam, a lab technician at the medical complex who sheltered in the bunker with his daughter and wife. The temperature often dipped below freezing during the night, and the limited sun did little to warm up the bunker.16

Medical staff were inside the hospital complex, tending to patients, including pregnant women and sick, or injured children.

In the bunker nearby, civilians huddled in the dark. It was a waiting game, one that required strategy and luck to secure the basics: water for drinking and washing, food for eating, supplies for tending to wounds, any means to use the bathroom.

At around 2:50 p.m. on March 9, residents near the hospital

The attack appeared to target the hospital complex, damaging the maternity unit and children’s diagnostic unit, and leaving a deep crater in one of the hospital’s courtyards.18

Facts about the attack

- Building: Hospital #3

- Coordinates: 47.096906, 37.533441

- Date: March 9, 2022

- Military forces in the vicinity at the time of attack: Russian officials made several unfounded claims relating to the hospital. Just a couple of hours before the attack, Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova claimed that Hospital #3 was empty of patients – which analysis shows it was not – and being used by Ukrainian forces as a firing position. On March 10, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said Russian forces targeted the hospital because the Azov battalion was using it as a base. Witnesses said about 10 members of Ukrainian forces were positioned as guards in the hospital, but this would not make the facility a legitimate military target.

- Weapon used: An analysis of the crater and the damage to nearby buildings indicate that the explosion was caused by a 500-kilogram aircraft bomb that uses an impact fuze.

- Death toll: Ukrainian officials reported that the attack killed two adults and a child and wounded 17 medical staff and patients. A volunteer at the hospital who helped injured patients told Human Rights Watch he saw between 12 and 15 injured people immediately following the attack.

The hospital was one of 19 in Mariupol damaged during the fighting. By the end of March 2022, all of the city’s hospitals had “effectively ceased to function,” the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights said.19

Following the attack, patients and medical staff poured out of the facility. Several Ukrainian national police personnel and volunteers trudged through the mud carrying Iryna Kalinina, a wounded pregnant woman on a stretcher who gripped her abdomen in distress, blood soaking her pants. She died later that day, along with her baby, who was reportedly delivered via caesarean section following the attack but showed no signs of life.20 On March 10, Ukrainian officials said the attack killed at least two adults and a child, and injured 17 patients and medical staff.

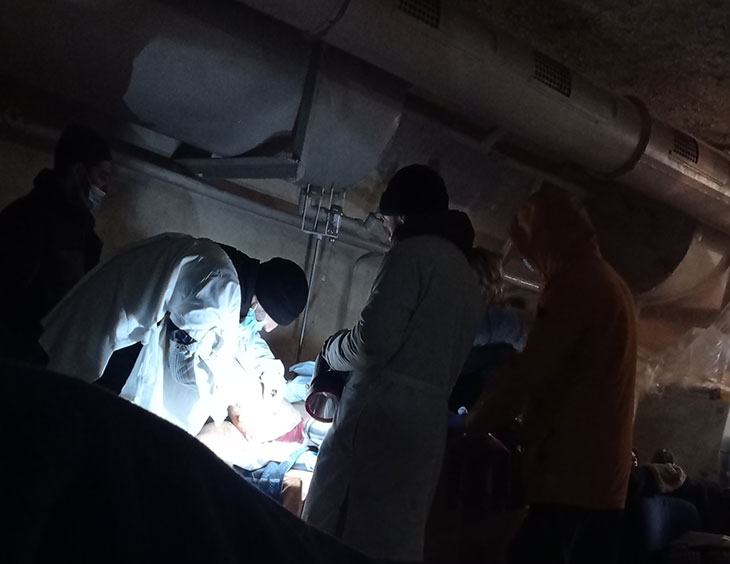

Medical staff transferred patients to other medical facilities, some of which were also struck during attacks. Some survivors went into the hospital’s underground bunker. At least 57 people sought shelter there, one witness said, including 30 children of medical staff and injured children who were being treated at the hospital at the time of the attack. Some young children arrived alone, without their parents.

“It was dark and cold, and our collective breath created a lot of moisture,” said Diana who sheltered there and tended to wounded civilians. “Everything was soggy. At night, I was covered in several blankets, and they were all disgustingly moist and cold.” 21

Doctors performed rudimentary surgery, bandaging wounds, administering injections, removing shrapnel, and amputating one man’s hand with a bayonet knife.22 They deposited trash and other waste, including human waste, outside the bunker on a ramp. It was there, too, where they placed the remains of those who died, according to Diana, including the body of a girl who died in the shelter.

Meanwhile, throughout March, attacks continued to hit the medical complex. As blast waves rocked the heavy doors of the bunker, those sheltering inside came up with activities to distract the children.23

“To help their mood, we gave them simple tasks like sorting pills, which they did with great eagerness and meticulousness,” said Rustam, whose wife worked in the hospital.

With no way to bring food into the city and few shops sporadically open, people across Mariupol survived on food from their apartments or shared by people in shelters who risked their lives scavenging for it in nearby buildings. Food was scarce: two oranges divided among 20 people; boiled potatoes and a can of meat stew was dinner for dozens.24 Volunteers who left the hospital complex bunker in search of food and water, or to restart the generators, sought cover from aircraft and drones overhead. 25

Across the city, thousands of people endured similar conditions, doing what they could to survive.

“Without [the volunteers’] help, we would have likely starved to death,” said Diana.26 Children cried from hunger, she said, their bellies mostly empty.

Without running water, people tapped fire hydrants, collected rainwater in buckets, melted snow, and dodged shelling to fetch water from springs and wells. Venturing outside to get water was risky; some people never returned.

Those sheltering in the hospital’s bunker were comparatively lucky. There was an old water reservoir inside, though nobody knew how old the water was, and a well close by in a park. But it didn’t come without risk.

“The way to the well was covered with corpses,” Diana said. “Those people who were brave enough to go there were likely to become our patients with pieces of [their bodies] torn off.”27

Documenting Destruction

On March 9, minutes after the attack on Hospital #3, Mykhailo Puryshev heard an aircraft approaching.28

“Run!” he screamed, rushing with a group of people into a building at Pryazovskyi State Technical University, one of the oldest educational institutions in the region.

As he ran, Puryshev held his phone up, selfie style, recording. An explosion is heard on the video, throwing him forward. And then another blast. The university was under attack.

“Everybody go down, careful!” Puryshev said. A shock wave pushed him inside the building. It was hard to breathe. Everything went dark. A man cursed; a child wailed.

Before the war, students in over 200 educational programs there studied engineering, metallurgy, transportation, economics, and information technology.29

Puryshev owned a restaurant called “Evo” next to the campus, where young people played video games and listened to music. But on that morning, there were no students grabbing a meal between classes or catching up with friends. The university was no longer for learning; it was a place to seek safety. Hundreds of people were sheltering in basement classrooms and corridors there, breaking radiators to find drinking water.30

“I went outside and saw the horror,” Puryshev recalled. “I started to cry for the first time.”

The attack appears to have killed at least two civilians, injured at least one more, and caused significant damage to the university.

Puryshev became one of many Mariupol residents who documented damage done to their city in real time, posting photographs, videos, and information to Telegram, TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, and elsewhere. They did so to inform the world about what was happening, to keep a record of their lived experience, and in some cases, to document what they thought would be their final moments.

Facts about the attack

- Building: Pryazovskyi State Technical University

- Coordinates: 47.095504, 37.5414040

- Date: March 9, 2022

- Military forces in the vicinity at the time: None of the seven witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they saw any Ukrainian military forces in the area at the time of the attack.

- Death toll: At least two confirmed dead and one injured

- Weapon used: Air-dropped munitions

- Damage to buildings: Significant damage to the northwest corner of Universytetska Street 7, the collapsed roof of Universytetska Street 9 just to the south, and damage to the roof of at least one other building, at Kazantseva Street 7, that forms part of the enclosed campus.

“The sky belonged to them,” he said, referring to the Russian Air Force. “And they did whatever they wanted.”

Our analysis of central Mariupol, using satellite imagery and open-source information, determined that 86 out of 89 educational facilities in Mariupol were damaged, including all 15 university campuses and 71 out of 74 school campuses.

In Mariupol, the once-bustling campus of Pryazovskyi State Technical University has now relocated some 300 kilometers away, to Dnipro, where students continue learning in person and online, despite the war.

Explosive Weapons, Deadly Consequences

Throughout the Russian offensive on Mariupol, the use of explosive weapons in populated areas unleashed death, destruction, and misery. This included shelling from tanks and heavy artillery, mortar projectiles, multi-barrel rocket launchers, missiles, and airstrikes that continually rained down.

Explosive weapons can have a large destructive radius, or are inherently inaccurate, or deliver multiple munitions simultaneously. They not only kill and injure civilians at the time of attack, but also have long-term ripple, or “reverberating,” effects by damaging infrastructure, inflicting psychological harm, causing lasting environmental damage, and displacing entire communities.

The devastating effect of these weapons was laid bare at Marinska Balka Street 67, a 10-minute walk from the Pryazovskyi State Technical University. There stood a community of single-family homes with colorful metal gates, nestled between trees and the city’s tramway. A bright red tram ran on tracks past the neighborhood. Survivors say a number of attacks destroyed at least 15 homes there.

Facts about the attack

- Building: Marinska Balka Street 67

- Coordinates: 47.10098, 37.53943

- Date: March 10, 2022

- Military forces in the vicinity at the time: A resident told Human Rights Watch that Ukrainian armored vehicles passed by his and his neighbors’ homes every day to distribute aid, but that they moved on after doing this and were never stationed near his home.

- Death toll: Human Rights Watch documented at least three deaths, in addition to one man who lost his legs but survived.

- Damage to buildings: Satellite imagery from March 12, 2022-the first available after the attack-shows damage to the southwest corner of Marinska Balka Street 67 and severe damage to the adjacent houses, some of which are completely destroyed.

The ceiling collapsed onto Vladyslav’s sleeping family.

“The garden shed had been blown into the living room and one of the living room doors was destroyed,” he said. “The windows and doors were gone.” The family emerged unscathed.

The home opposite theirs was in flames.

“I helped a young man and his mother-in-law escape from the [neighbor’s] house,” he said. “But the young man’s wife and her sister were screaming as they were trapped under the collapsed roof. They burned to death.”

In a nearby house, someone screamed for help. Solomiia grabbed a cloth for a tourniquet and rushed outside. The house opposite was gone. Her neighbor’s legs were blown off. He begged Solomiia to save the 12-year-old girl next to him whose her legs were crushed by a wall.

Solomiia was able to save the man’s life, but his legs were later amputated. The girl died.

The community around Marinska Balka Street 67 was one of many damaged by explosive weapons.

Through satellite imagery analysis, as well as verification of photographs and videos posted online, we determined that 54 percent of buildings (4,884 out of 9,043) we surveyed in the part of central Mariupol where we focused our damage analysis were damaged or destroyed. Ninety-three percent of high-rise buildings (433 out of 477) were damaged, as well as almost half of single-story homes, like those on Marinska Balka Street.

In June 2022, a journalist with a Russian government broadcaster posted a video to social media showing workers in hazmat suits walking through the once cozy Marinska Balka Street neighborhood.33 They walked past a crumpled blue bicycle and the gutted remains of homes that once lined the street, carrying bodies that had been there for months.

Burying the Dead

In neighborhoods across the city, residents watched as their communities became battlegrounds and, ultimately, graveyards.

Despite the danger outside, Stanislav decided to leave his home near the seaside on March 8, 2022, to deliver food to a friend with a disability. The five-story building, more than a kilometer and a half from the single-family homes around Marinska Balka Street 67,34 stood within a city neighborhood surrounded by banks, stores, a shopping center, and a playground.

Facts about the attack

- Building: Torhova Street 20

- Coordinates: 47.09357, 37.55960

- Date: March 8, 2022

- Military forces in the vicinity at the time: A witness to the attack told Human Rights Watch that he saw no soldiers or military vehicles in the street on the day of the attack.

- Death toll: At least five people, including two children, were killed.

- Damage to building: Satellite imagery from March 10, 2022 — the first available after the attack — shows damage to the middle section of the roof, as well as debris next to the eastern side of the building. Analysis of additional satellite imagery shows the building was subsequently damaged four times.

Late that afternoon, Stanislav and his friend were smoking downstairs, with the sound of explosions in the distance. As he looked around, he saw three women and a boy, who appeared around 10, and a girl, about 12, standing in front of a three-story building, at Torhova Street 20.

“Suddenly we heard a sound of something coming down from the sky,” he said. “The sound was slow and heavy. I also didn’t see any soldiers or any vehicles.”

Then, a flash, and smoke. Stanislav watched, as if in slow motion, as the roof of the nearby building collapsed. He and his friend fled, returning 10 minutes later to see if anyone was injured.

“I saw five bodies on the ground,” he said. He realized it was the three women and two children he had seen just moments before.

Stanislav didn’t want to leave the bodies where they had fallen. He and a friend dragged the children across the street, to the playground, which had a sandbox pit and a cover, and left them there. It was a crude makeshift grave, the best they could provide. It wasn’t safe to be outside.

Just weeks before, children had flocked here to play. Now, it was an unmarked grave holding children’s maimed bodies.

Faced with an onslaught of fighting, many people were unable to bury loved ones or other victims. For some, a makeshift grave was a shallow pit dug next to a residential building with a cross fashioned out of wood, or a children’s football field. For others, it was a trench for 200 bodies dug in haste as the war’s front line crept closer.35

Counting the Dead

Death was everywhere in Mariupol; it was impossible to avoid, with bodies scattered in the streets, alone in apartments, and buried in shallow graves.

The thought of dying scared Rostyslav, a 46-year-old boiler operator who helped maintain Mariupol’s heating network. But on March 22, he was hungry.36 And that meant going outside to cook borshch, a traditional beet soup, in the courtyard of Myru Avenue 42, a classic mid-century building with high ceilings and large windows just next to the Drama Theater.

“Suddenly, I heard an attack hit the other side of the building, the side facing the theater,” he said. “I saw the building shake.”

Facts about the attack

- Building: Myru Avenue 42

- Coordinates: 47.09475, 37.55154

- Date: March 22, 2022

- Death toll: At least two people were killed.

- Damage to buildings: Two images show the extent of the damage to the roof and western side of the building. A video uploaded on July 15, 2023, shows fire damage on the inside. A video recorded by Reuters also shows residents digging graves outside of Myru Avenue 42 in early April. Satellite imagery from March 21, 2022, shows some damage to the roof of the building. Satellite imagery from March 24, 2022, after the March 22 attack, shows additional damage to the roof and smoke rising from the building.

A man ran out of the building saying it had been hit. There were people who needed help.

Rostyslav ran inside with two other men, to an apartment now in ruins on the third floor. There he found Denis and Asya, a couple in their thirties with whom he had been sheltering in the basement. Denis and Asya had gone up to their apartment just before the attack to collect some belongings, leaving their two children, whom Rostyslav estimated to be 6 and 14, with their grandparents in the shelter below.

When Rostyslav entered the destroyed apartment, he found Denis and Asya in their bathroom under a collapsed wall.

Asya “died in my arms,” said Rostyslav. Denis was buried deeper under the rubble. “He was screaming from the pain, and he was in shock.” Rostyslav dug him out. A nurse administered intravenous (IV) fluids, hoping to save Denis, but he died an hour later.

Rostyslav placed their bodies together on the sofa, in the destroyed remains of the apartment. It was too dangerous to bury them; the shelling was constant.

“We realized we had to escape as soon as possible,” he said. Rostyslav and the other men wept for the people they could not save.

The next day, Rostyslav left Mariupol, risking the 30-kilometer walk, away from the bombs and the destruction, and far from his city.

He was one of the fortunate ones: during the first half of March 2022, it was nearly impossible for civilians to leave the besieged city, with evacuation attempts repeatedly called off at the last minute, in the face of Russian obstruction. Ukrainian authorities also accused Russian forces of blocking humanitarian aid from reaching the city.

Despite continued fighting, a reported ceasefire agreement on March 14 allowed tens of thousands of people to escape Mariupol in cars for Ukrainian-held Zaporizhzhia in the second half of March and April. Some, like Rostyslav, fled on foot.

Those fortunate enough to have working vehicles met at places like Myru Avenue 42 to join hundreds of cars that wove through the countryside as they tried to make it to relative safety. The journey of less than 300 kilometers often took two or three days as they passed dozens of checkpoints manned by Russian and Russia-aligned officials who often searched, interrogated, and occasionally detained those fleeing. It was especially difficult for older people, caregivers, people with disabilities, and those with serious injuries to make the journey. It was only on April 30 that the first official evacuations of civilians from Mariupol to Ukrainian-held territory took place, with further evacuations the following week involving the United Nations and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Many left behind loved ones. Bodies were rolled in carpets, left on benches, lying near walls, piled up behind garages. Spring brought new horrors, as bodies began to decompose and the smell overpowered parts of the city.

“Seeing dead bodies became the new normal in Mariupol,” said Olena, who survived multiple attacks on her building before making it into an evacuation convoy.

“As we drove out of the city, we saw it was all burned and black,” said Olena of the apocalyptic scene out the bus window on the drive out of Mariupol in late March. “We cried. Our city was gone.”39

Remains were being pulled from the rubble as late as February 2023, said Oleg Morgun, Mariupol’s mayor installed by Russian occupation forces.40 Thousands of people died during the assault on and siege of Mariupol and in the months that followed, including those killed during attacks and many who died because they did not have access to clean water or adequate health care.

Based on our analysis of five mass burial sites in and around Mariupol, at least 10,284 people -an unknown number of soldiers among them-were buried in these graves between March 2022 and February 2023. This is the minimum number of people buried during this period and is most likely a significant underestimate of the total number of people who died during this period, given that the remains of some victims may have disappeared in the rubble of destroyed buildings, some graves may contain multiple bodies, and some of the injured or sick may have died or been buried outside of the city. It will probably take many more years to get a full accounting of all those from Mariupol who were killed or died during this period.

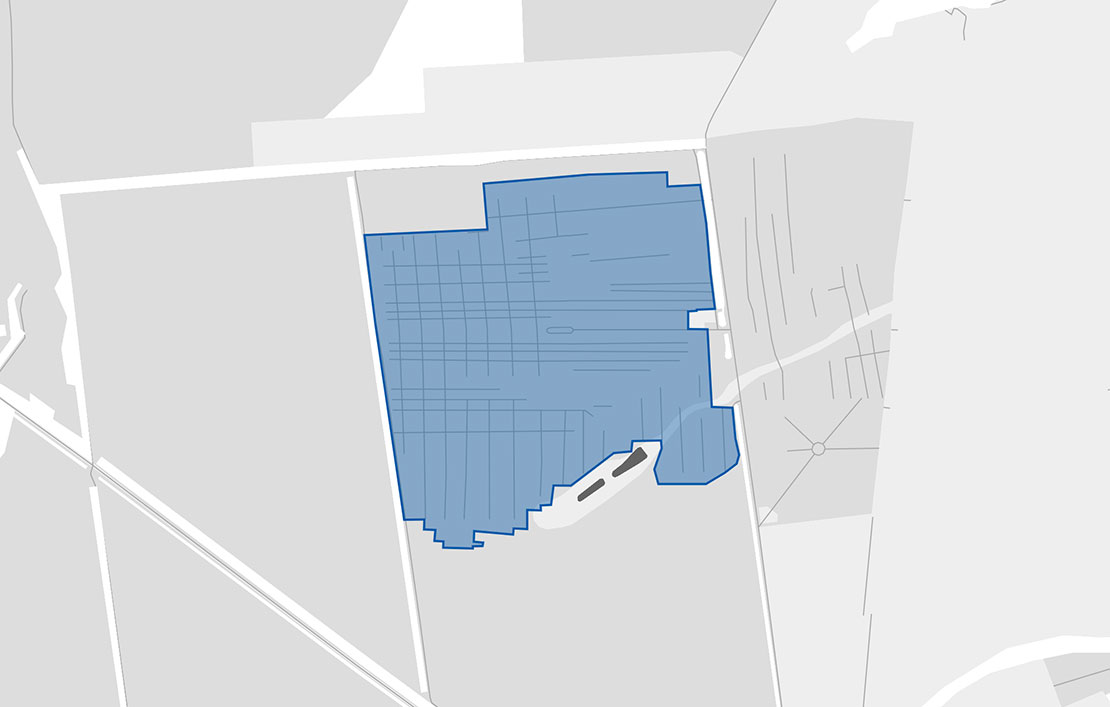

Human Rights Watch, SITU Research and Truth Hounds identified four cemeteries in the city that saw a significant increase in the number of graves and where thousands were buried in individual and trench-like graves: Starokrymske, Novotroitske, Vynohradne and Pavlov Street cemetery. We also identified hundreds of burials in a cemetery just outside of the city, in the town of Manhush.

Manhush: 315

Starokrymske: 8,580

Pavlov Street cemetery: 45

Vynohradne: 864

Novotroitske: 480

The cemeteries hold thousands of bodies, many still unidentified.

Stefaniia, who has only found one of her loved ones – little Arina – out of four relatives killed in Mytropolytska Street 98, assumes the rest of her family is buried in one of these cemeteries.

“I feel their presence,” she says. “I have to find them.”

A City Devastated, Rebuilt in Russia’s Image

For many Mariupol residents, the collective trauma of losing so many people has been compounded by what they say is a loss of identity.

Before Russia’s invasion, Mariupol’s iconic Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theater was a place of cultural celebration.

The arched entrance was topped by a stone carving of men and women carrying instruments, wheat, and tools, a celebration of the region’s culture.

Residents gathered outside every holiday season, the area twinkling with Christmas lights.

The theater, like other cultural landmarks, became a bunker overnight after the Russian attack on the city began. Civilians hoped the building, designated as a public shelter, would protect them from bullets and bombs. They were wrong.

On March 16, 2022, hundreds of people were sheltering inside the theater. Out front, in the plaza, the word “дети,” or “deti,” written on the pavement in huge white script was visible to any passing aircraft. The meaning of those Cyrillic letters, also visible on satellite imagery, was clear: Children.

Civilians, including many children, sheltered inside. For days they had entered and exited the theater, cooked and collected water outside, and received aid from Ukrainian soldiers and volunteers out front.

Just before midday on March 16, Maksym saw a plane fly in from the east, over the Azovstal factory, descending as it got closer to Myru Avenue, and then dropping two bombs.41

Nataliia Tkachenko had just returned to the theater’s entrance after collecting water outside from a water tank.42

“I felt a sudden flow of air and then something in my eyes and mouth,” she said. “I stood there, holding onto a friend in disbelief.”

The attack destroyed the central part of the roof as well as the central part of the northern and southern walls.

“I saw an older woman crawl slowly from the basement,” Tkachenko said. “I went outside and saw a young blonde woman covered in blood. There was debris everywhere and I saw a leg sticking out of it in one place and a hand in another place.”

Our research team documented that at least 15 people were killed as a result of the attack, but the total number has not been determined.

Facts about the attack

- Building: Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theater

- Coordinates: 47.09600, 37.54864

- Date: March 16, 2022

- Military forces in the vicinity at the time: Human Rights Watch interviewed eight witnesses who were in or near the theater at the time of the attack or in the immediate aftermath, and reviewed reports from Amnesty International, media outlets, and the Ukrainian government. Witnesses said that members of the Ukrainian army and Territorial Defense Forces would sometimes drive by the theater to drop off food and medicine, and at times patrolled on foot nearby. However, none of them saw any Ukrainian armed forces or vehicles outside the theater at the time of the attack. We found no evidence that Ukrainian military forces were in or around the theater before or at the time of the attack, making the attack unlawful, and those who ordered it or carried it out responsible for an apparent war crime.

- Death toll: Human Rights Watch estimates that several hundred people were in the theater at the time of the attack. Based on Human Rights Watch, Truth Hounds, and Amnesty International interviews, and the names of people published on traditional and social media, we believe that at least 15 people died in the attack. International media have reported on claims that between 60 and 200 were killed. The Associated Press carried out its own assessment and estimated that up to 600 people died. In July 2022, “DNR” officials said they had found 14 bodies in the theater’s ruins.

- Weapon used: The attack was most likely carried out by Russian aircraft that dropped two 500-kilogram bombs onto the theater’s roof, which then penetrated the building and detonated in the main auditorium at about stage level, possibly with the aid of delayed-action fuses, according to Human Rights Watch’s analysis and reporting by Amnesty International.

Over the next year, occupying Russian forces demolished most of the Drama Theater, constructing a tall fence around the site. Two-story portraits of classical Russian and Ukrainian writers and historical figures have decorated the scaffolding: the poet Alexander Pushkin, the author Leo Tolstoy, the novelist and playwright Nikolai Gogol, and, perhaps most jarringly, the celebrated literary figure Taras Shevchenko, long considered a symbol of Ukraine’s fight for sovereignty.

Across the city, occupying forces marked 459 buildings for demolition, 148 of which are in central Mariupol, according to a May 2023 list published on the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic (“DNR”) website.43

Our analysis shows that at least 66 high-rise apartment buildings damaged during the siege had been demolished in central Mariupol as of February 9, 2023.

In June 2023, two Russian companies, MCT and Geostroy, began tearing down Mytropolytska Street 98, where Arina and her family died in the basement.44

On Telegram, former Mytropolytska Street residents reacted to the news alongside a photo and drive-by footage showing a low rubble pile where Mytropolytska Street 98 once stood. “Теперь только воспоминания,” wrote one individual: “Now, only memories.”

Human Rights Watch reviewed satellite imagery of the site. As of late June 2023, nothing remained.

Occupying forces — and workers who are sometimes hired to do the difficult work – have cleared millions of tons of rubble from Mariupol, transporting it to dump sites around the city. That debris, once people’s homes and belongings, will be used by Russian authorities to rebuild the occupied city.

“At the landfill, it is planned to process 1.5 million tons of construction waste annually, which were formed as a result of repair and restoration work, including the dismantling of buildings and structures,” said Natalia Mnatsakanyan, a news anchor for the Russia-occupation controlled Mariupol 24, in a report posted to their Telegram account in February.45 The material “obtained from recycling will be used in construction,” she added.

In August 2022, Russia’s Construction Ministry announced plans to “restore” Mariupol within three years.46 The plan, promoted by Denis Pushilin, the head of the “DNR,” appears to have been commissioned by the Russian Construction Ministry and prepared by a Russian federal organization called the Unified Institute of Spatial Planning.47

According to the plan, Russian authorities expect some 350,000 people – up from the current estimate of about 150,000 – to live in Mariupol by 2025, 450,000 by 2030, and 500,000 by 2035.

Hundreds of thousands of Mariupol residents now live outside their city, some displaced to other parts of Ukraine, some abroad as refugees.

Meanwhile, unknown numbers of Mariupol’s original inhabitants remain missing, some of them presumed dead, others transferred to Russia, willingly or forcibly.

On February 25, 2023, the Kremlin put on a lavish event at Moscow’s Luzhniki stadium, to mark one year since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Onstage, in front of thousands of cheering onlookers, Russian leaders paraded children from Mariupol, recognized by Mariupol survivors who watched the footage from afar, the Guardian reported.

Several weeks later, on March 19, just over a year after Russian forces besieged Mariupol, and two days after the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for President Vladimir Putin for war crimes involving the unlawful deportation and transfer of Ukrainian children, the Russian president paid an unexpected visit to Mariupol.

Landing by helicopter at night, he drove down Myru Avenue and toured the surrounding area, visiting key landmarks and inspecting what the Russian occupation forces called “construction and restoration” plans.48

He walked through Mariupol’s elegant Philharmonic Hall, just next to the destroyed Drama Theater. Gone was the orchestra’s lead conductor, Vasyl Kriachok, who fled in April 2022, setting up a new orchestra in Kyiv. Also gone were most of the orchestra’s musicians, scattered around the world.

Russian occupation authorities have been portraying reconstruction efforts as a rebirth of the city. But for many residents, constructing new buildings feels like erasing their history.

“You have every fence, every corner, you have some kind of definite memory with it,” said one Mariupol resident. “When your memories are destroyed, your childhood is destroyed, your native home is destroyed, to which you can no longer return.”

Survivors now circulate information about their former homes and what may become of them, if occupying forces plan to repair them or if they will tear them down, the raw materials collected by construction teams. Some buildings remain standing, for now, their gutted frames a reminder of what was lost.

“For me, it doesn’t matter anymore whether our house will be restored or other housing will be given to me,” one resident displaced from Mytropolytska Street posted in a public neighborhood Telegram group in February 2023, before their home was fully torn down. “The main thing is that there would be somewhere to live…I’m just tired.49

Meanwhile, the city is changing in other ways, too. Teachers are forced to sign a document certifying their willingness to switch to teaching the Russian school curriculum. It features a Kremlin-approved version of history that denies Ukraine’s sovereignty and erases it as an independent nation. Ukrainian education “will be adapted,” Russia’s Education Minister Sergey Kravtsov reportedly said in June 2022.50

Occupying forces have changed names of streets and squares, replacing some of them with names imposed during the Soviet era: Myru Avenue, the city’s Avenue of Peace, is now named Lenin Avenue, symbolic of the former Soviet Union and Russian domination of Ukraine. Television programming that was in Ukrainian before is now in Russian. Internet traffic is routed through Russian servers, and access to many Ukrainian sites, blocked.

As in other Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine, those who dare to resist these changes, or who speak out against the war and occupation, risk being arbitrarily detained, imprisoned, or forcibly disappeared.

As occupying forces build a new Mariupol, this one in Russia’s image, the war in Ukraine continues.

Residents of Mariupol, some displaced and dispersed around the world, and others who stayed, say they worry the siege and widespread damage done to their city will ultimately be forgotten. They worry, too, that they themselves will forget: the bedroom they grew up in, the number of the bus they took to work, performances at the Drama Theater.

For Stefaniia, who lost her family in the attack on Mytropolytska Street 98, memories are all she has left. She cherishes the videos on her phone showing her loved ones alive and happy.

That’s how she remembers Arina Antipenko, not as the tiny body she buried in the cold ground, but as the radiant child she adored, now forever three years old. Stefaniia’s daughter, Khrystyna, comes to her in her dreams most nights, she says.

Despite losing her family in Mariupol, she still feels connected to the city. Her daughter loved Mariupol. It’s where Arina was born. And where Ivan worked, saving up for their dream home. It’s where she took long strolls with Khrystyna, admiring Mariupol’s architecture, with its many parks and blooming flowers. “The city was beautiful,” she says. “Now, it’s darkness.”

Yet she has returned, flowers in hand, scattering them near Mytropolytska 98. There is no other place to go and pray, she says.

“This is the city of my children.”

Read more Human Rights Watch reporting on the Russia-Ukraine conflict »

Read more about SITU Research

Read more about Truth Hounds

Call to Action

Take a Stand for Human Rights in Ukraine:

Research, United, Advocate!

Join us to make a difference in Ukraine’s war-torn landscape. Research, collaborate, and engage with human rights organizations. Together, we can protect and promote human rights.

Acknowledgments

We thank the many individuals who made this research possible. We also acknowledge the individuals who documented the destruction of Mariupol, uploading photos and videos to social media. This documentation enabled our team to report on incidents with a higher level of accuracy and nuance.

Research and writing at Human Rights Watch by: Sophia Jones, Gerry Simpson, Alexx Perepölov, Robin Taylor, Carolina Jordà Álvarez, Léo Martine, Sam Dubberley, Devon Lum, Ekin Ürgen, Nīa Knighton, Gabi Ivens, Kseniya Kvitka, Belkis Wille, Richard Weir, Sumaya Tabbah, Ida Sawyer, Yulia Gorbunova, Oksana Pankova, and consultants Ilja Sperling, Valeriia Voshchevska, and Mariam Naiem.

Research at SITU Research by: Bora Erden, Evan Grothjan, Martina Duque Gonzalez, Brad Samuels, Candice Strongwater, Gauri Bahuguna, Grisha Enikolopov, and Helmuth Rosales.

Research at Truth Hounds by: Viktoriia Amelina, Bohdan Kosokhatko, Vladyslav Chyryk, Roman Avramenko, Roman Koval, Olena Prokopyshyna, Olha Vovk-Sobina, Natalya Zlyhostieva, Yaroslav Shyman, Viktoriia Babii, and Maryna Slobodianiuk.

Reviewed at Human Rights Watch by: Fred Abrahams, Bill van Esveld, Kathleen Rose, Anagha Neelakantan, Rachel Denber, Tanya Lokshina, Mark Hiznay, Brian Root, James Ross, Bridget Sleap, Karolina Kozik, Hillary Margolis, Kayum Ahmed, Stephen Northfield, and Balkees Jarrah.

Art direction and development by: Grace Choi and John Emerson

Design by: Studio Rodrigo

Published on February 8, 2024

1 Alessandra Prentice and Natalia Zinets, “Russia’s ‘victory’ in Mariupol turns city’s dreams to rubble,” Reuters, April 26, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-victory-mariupol-turns-citys-dreams-rubble-2022-04-26/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

1 Alessandra Prentice and Natalia Zinets, “Russia’s ‘victory’ in Mariupol turns city’s dreams to rubble,” Reuters, April 26, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-victory-mariupol-turns-citys-dreams-rubble-2022-04-26/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

2 “Meeting with Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu,” Presidential Executive Office news release, April 21, 2022, http://www.en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/68254 (accessed July 11, 2023).

3 Mariupol Now (@mariupolnow), post to Telegram channel, June 13, 2022, https://t.me/mariupolnow/13391 (accessed December 12, 2023).

4 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Dmytro Lastenko, October 29, 2022.

5 Список мест для возможного укрытия населения Мариуполя (АДРЕСА), Official site of the Mariupol City Council, https://mariupolrada.gov.ua/news/perelik-misc-dlja-mozhlivogo-ukrittja-naselennja-mariupolja-adresa (accessed February 24, 2022).

6 Now-deleted account, post to Telegram channel, March 15, 2022, https://t.me/mitropolitskaya_giguli/1409 (accessed July 11, 2023).

7 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Pavlo, March 28, 2023.

8 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Danylo, October 22, 2022.

9 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Stefaniia, April 25, 2023.

10 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Pavlo, March 28, 2023.

11 Human Rights Watch interview with Maryna, Kyiv, September 21, 2022.

12 Ibid.

13 Погибшие, Память, Мариуполь (@mariupolRIP), https://t.me/mariupolRIP (accessed April 24, 2023).

14 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Pavlo, March 28, 2023.

15 Homepage, Mariupol Medkontrol, https://mariupol.medkontrol.pro/mtmo-zdorovya-rebenka-i-zhenshhiny (accessed July 12, 2023).

16 Human Rights Watch interview with Rustam, Dnipro, June 17, 2022.

17 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Demian, June 21, 2022.

18 Ibid.

19 “High Commissioner updates the Human Rights Council on Mariupol, Ukraine,” OHCHR, June 16, 2022, https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2022/06/high-commissioner-updates-human-rights-council-mariupol-ukraine (accessed July 11, 2023).

20 Alex Stambaugh, Tim Lister and Olga Voitovych, “Pregnant woman and her baby die after Mariupol maternity hospital bombing,” CNN, March 14, 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/14/europe/mariupol-pregnant-woman-baby-death-intl/index.html (accessed July 12, 2023).

21 Human Rights Watch interview with Diana, Dnipro, June 21, 2022.

22 Human Rights Watch interview with Rustam, Dnipro, June 17, 2022.

23 Human Rights Watch interview with Rustam, Dnipro, June 17, 2022.

24 Human Rights Watch interview with Diana, Dnipro, June 21, 2022.

25 Human Rights Watch interview with Viktoriia, Dnipro, June 16, 2022.

26 Human Rights Watch interview with Diana, Dnipro, June 21, 2022.

27 Ibid.

28 Human Rights Watch interview with Mykhailo Puryshev, Kyiv, October 25, 2022.

29 Human Rights Watch interview by email with Balalaeva Olena Yuriivna, June 28, 2023.

30 Human Rights Watch interview with Davyd, Dnipro, June 12, 2022.

31 Human Rights Watch interview with Vladyslav, Lviv, May 2, 2022.

32 Human Rights Watch interview with Solomiia, Dnipro, May 6, 2022.

33 “Мариуполь/Живые и мертвые,” June 8, 2022, video clip, Dzen, https://dzen.ru/video/watch/62a093267933a4355bf38f6f?utm_referrer=statics.teams.cdn.office.net (accessed December 12, 2023).

34 Human Rights Watch interview with Stanislav, Lviv, May 3, 2022.

35 Human Rights Watch interview with Vaagn Mnatsakanian, Arles, October 12, 2022.

36 Human Rights Watch Interview with Rostyslav, Dnipro, May 6, 2022.

37 Mariupol City Council (Маріупольська міська рада) (@mariupolrada), post to Telegram channel, March 15, 2022, https://t.me/mariupolrada/8861 (accessed July 11, 2023).

38 Mariupol City Council (@mariupolrada), post to Telegram channel, March 18, 2022, https://t.me/mariupolrada/8893 (accessed July 11, 2023).

39 Human Rights Watch Interviews with Aryna and Olena, Lviv, April 19, 2022.

40 “Снос разрушенных многоэтажек в Мариуполе закончат в этом году,” RIA Novosti, February 13, 2023, https://ria.ru/20230213/mariupol-1851596718.html (accessed January 20, 2024).

41 Human Rights Watch interview with Maksym, Kyiv, September 12, 2022.

42 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Nataliia Tkachenko, June 16, 2022.

43 Единый реестр зданий и сооружений, подлежащих сносу, Ministry of Construction and Housing and Communal Services, https://minstroy-dnr.ru/snos-jilya (accessed December 11, 2023).

44 Митрополитская, р-н “Жигули” (@mitropolitskaya_giguli), post to Telegram channel, May 27, 2023, https://t.me/mitropolitskaya_giguli/12848 (accessed July 11, 2023).

45 Mariupol 24(@mariupol24tv), post to Telegram channel, February 10, 2023, https://t.me/mariupol24tv/20566 (accessed September 4, 2023).

46 Мастер-план Мариуполя предполагает восстановление города за три года, Official website of the Ministry of Construction, Housing and Utilities of the Russian Federation, https://minstroyrf.gov.ru/press/master-plan-mariupolya-predpolagaet-vosstanovlenie-goroda-za-tri-goda/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

47 Мастер-план Мариуполя предполагает восстановление города за три года, EIPP, https://eipp.ru/news/2022/master-plan-mariupolya-predpolagaet-vosstanovlenie-goroda-za-tri-goda.html (accessed July 11, 2023); Decree of the Head of the Donetsk People’s Republic No. 420 of July 30, 2022, About the Concept of the Master Plan for the Development of the City of Mariupol, http://npa.dnronline.su/2022-07-30/ ukaz-glavy-donetskoj-narodnoj-respubliki-420-ot-30-07-2022-goda-o-kontseptsii-master-plana-razvitiya-goroda-mariupol.html (accessed December 21, 2023).

48 Official Website of the President of Russia, “Рабочая поездка в Мариуполь,” video report, March 19, 2023, http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/70742, (accessed July 11, 2023).

49 Митрополитская, р-н “Жигули” (@mitropolitskaya_giguli), post to a Telegram channel, February 7, 2023, https://t.me/mitropolitskaya_giguli/ 12163%20Post%20to%20a%20Telegram%20 group,%20February%207 (accessed December 5, 2023).

50 Единая Россия. Официально (@er_molnia), post to Telegram channel, June 28, 2022, https://t.me/er_molnia/4221 (accessed January 10, 2023).