After five months of UN-brokered political talks between Libyan stakeholders, the country’s House of Representatives swore in on March 15 a new interim authority, the Government of National Unity (GNU).

As of October, the first round of a two-round presidential election was due to take place on December 24. Parliamentary elections were due to take place 52 days after the first round of presidential elections.

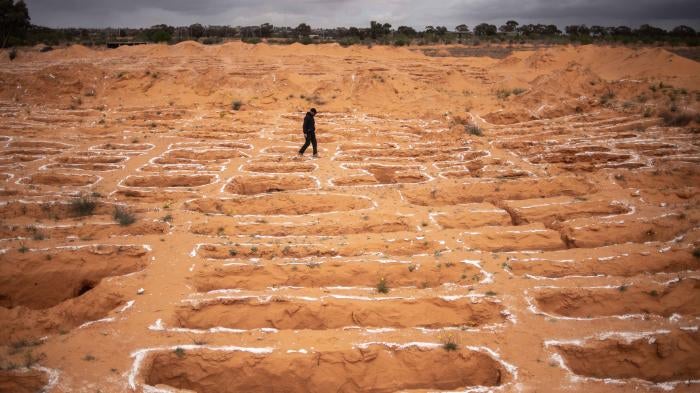

The country reeled from continued mass displacement, dangers caused by newly-laid landmines, and the destruction of critical infrastructure, including healthcare and schools. Hundreds of people remain missing, including many civilians, and the authorities made grim discoveries of mass graves containing dozens of bodies that remain unidentified.

Migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees in Libya faced arbitrary detention, during which many experienced ill-treatment, sexual assault, forced labor, and extortion by groups linked with the Government of National Unity’s Interior Ministry, members of armed groups, smugglers, and traffickers.

Political Process and Elections

UN-facilitated political talks involving 75 Libyan stakeholders at the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF) since November 2020 culminated in the nomination of the GNU. The new interim authority replaced the Government of National Accord and the Interim Government in eastern Libya.

While members of a joint military commission known as the 5+5 were negotiating the merging of Libyan fighters into a unified force, the Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LAAF), the armed group under the command of General Khalifa Hiftar, remained in control of eastern Libya and parts of the south.

The GNU’s core mandate is to conduct presidential and parliamentary elections on December 24 and to implement a ceasefire agreement from October 2020 between parties. As of October, the House of Representatives (HOR) passed a law for electing a president on December 24, and a separate law on electing a new parliament, paving the way for national elections. The High Council of the State, mandated to approve elections laws per political agreements, contested the legislation citing lack of consultation.

Libya remains without a permanent constitution, with only the 2011 constituent covenant in force. A draft constitution proposed by the elected Libyan Constitution Drafting Assembly in July 2017 has yet to be put to a national referendum. As of October, no date had been scheduled for the referendum.

The constitutional chamber of the Supreme Court has remained shuttered since 2014 due to armed conflict. The lack of a constitutional court to review and revoke legislation deemed unconstitutional, including elections-related legislation, only deepens Libya’s constitutional crisis.

Armed Conflict and War Crimes

The October 2020 ceasefire agreement between former Government of National Accord and Hiftar’s LAAF stipulated the departure of all foreign fighters from the country. According to the UN mission in Libya, as of September, thousands of foreign fighters from Syria, Russia, Chad, and Sudan, including members of private military companies, remained in Libya.

Since the discovery of mass graves in the town Tarhouna after the end of the armed conflict in June 2020, Libyan authorities said they had retrieved more than 200 bodies from more than 555 mass graves as of October. The Public Authority for Search and Identification of Missing Persons as of October had yet to confirm how many individuals were identified based on DNA matching or other means, such as clothing.

The use of landmines during the armed conflict in Tripoli and surroundings, reportedly by the Wagner Group, a Russian government-linked company, has killed and maimed dozens of people and deterred families from returning to their homes. In September, eight members of one family were injured when a landmine exploded near their home in southern Tripoli. According to a March report by the UN Panel of Experts on Libya, internationally banned antipersonnel landmines manufactured in Russia and never before seen in Libya were brought into the country and used in Libya in 2019 and early 2020.

Judicial System and Detainees

Libya’s criminal justice system remained dysfunctional in some areas due to years of fighting and political divisions. Where prosecutions and trials took place, there were serious due process concerns and military courts continued to try civilians. Judges, prosecutors and lawyers remained at risk of harassment and attacks by armed groups. Libyan courts are in a limited position to resolve election disputes, including registration and results.

Libya’s Justice Ministry as of August held 12,300 detainees, including women and children, in 27 prisons under their control and other detention facilities “acknowledged” by the GNU, according to the UN Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL). Forty-one percent of the detainees were held in arbitrary, long-term pre-trial detention, according to UNSMIL. Armed groups held thousands of others in irregular detention facilities. Prisons in Libya are marked by inhumane conditions such as overcrowding and ill treatment.

Libyan authorities in March deported to Tunisia 10 Tunisian women and 14 children held in Libyan prisons, some for more than 5 years, for having ties to suspected members of ISIS.

The Libyan Supreme Court in May annulled a 2015 verdict against Gaddafi-era officials whose prosecution and trials for their roles during the 2011 revolution had been marred by due process violations. Muammar Gaddafi’s son Saif al-Islam was among nine sentenced to death. The Supreme Court ordered a retrial, yet at time of writing none of the defendants had appeared in court.

Authorities in western Libya on September 5 released eight detainees linked with former leader Muammar Gaddafi held since 2011, including one of Gaddafi’s sons, Al-Saadi, held since 2014 after his extradition from Niger. A Tripoli appeals court in April 2018 had cleared Al-Saadi of all charges, including first degree murder, yet he remained held in arbitrary detention and subjected to ill-treatment for three more years.

International Justice and the ICC

The International Criminal Court’s (ICC) former prosecutor in May reported to the Security Council that members of her office had traveled to Libya and interviewed witnesses but she did not announce any new arrest warrants against Libyan suspects.

Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, wanted by the ICC since 2011 for serious crimes during the 2011 uprising, remains a fugitive and Libya remains under legal obligation to surrender him to the Hague.

Al-Tuhamy Khaled, former head of the Libyan Internal Security Agency and wanted by the ICC for crimes he allegedly committed in 2011, reportedly died in Cairo in February; Mahmoud el-Werfalli, a commander linked with the LAAF and wanted by the ICC for multiple killings in eastern Libya, was reportedly killed in March in Benghazi by unidentified armed men.

Khalifa Hiftar faces three separate lawsuits filed in a US District Court in Virginia by families who allege their loved ones were killed or tortured by his forces in Libya after 2014. In July, the judge ruled that Hiftar cannot claim head-of-state-immunity in his defense.

The Libya Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) established by the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) in June 2020 to investigate alleged violations and abuses since 2016 only became fully operational in June due to delays caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. On October 3, the FFM issued its report, which found that “several parties to the conflicts violated International Humanitarian Law and potentially committed war crimes.”

On October 11, the HRC renewed the mission’s mandate for an additional nine months to allow completion of its investigations.

Death Penalty

The death penalty is stipulated in over 30 articles in Libya’s penal code, including for acts of speech and association. No death sentences have been carried out since 2010, although both military and civilian courts continued to impose them.

Freedom of Association

Libya’s Penal Code levies severe punishments, including the death penalty, for establishing “unlawful” associations, and prohibits Libyans from joining or establishing international organizations unless they receive government permission.

Presidential Decree 286 on regulating NGOs, passed in 2019 by the former Presidential Council of the GNA, includes burdensome registration requirements and stringent regulations on funding. Fundraising inside and outside Libya is prohibited. The decree mandates onerous advance notification for group members wanting to attend events. The Tripoli-based Commission of Civil Society, tasked with registering and approving civic organizations, has sweeping powers to inspect documents and cancel the registration and work permits of domestic and foreign organizations.

Freedom of Speech and Expression

Authorities in eastern Libya on September 11 released freelance photojournalist Ismail Abuzreiba al-Zway, who had been detained since December 2018. In May 2020, a Benghazi military court had sentenced him in a secret trial to 15 years in prison for “communicating with a TV station that supports terrorism.” The General Command of the LAAF reportedly granted al-Zway amnesty, but the conditions of his release were not publicized.

In October, the Libyan parliament passed a cybercrime law that appears to contain overbroad provisions and draconian punishments including fines and imprisonment that could violate freedom of speech.

A number of provisions in Libyan laws unduly restrict freedom of speech and expression including criminal penalties for defamation of officials, the Libyan nation and flag, and insulting religion. The penal code stipulates the death penalty for “promoting theories or principles” that aim to overthrow the political, social or economic system.

Human Rights Defenders

In April, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), responding to a complaint filed in 2017 by Libyan human rights defender Magdulien Abaida, found that Libya had violated the human rights of an activist “by failing to investigate and prosecute her unlawful arrest and torture by a militia group affiliated with the government.” In August 2012, the armed group Martyrs of 17 February Brigade, had seized Abaida from a hotel in Benghazi during a workshop and over the course of five days moved her between different military compounds while subjecting her to threats, harassment, insults and beatings. Abaida fled Libya soon after the group released her and was granted asylum in the United Kingdom.

Mansour Mohamed Atti al-Maghribi, a civic activist and head of the Red Crescent Society in the eastern town of Ajdabiya, has been missing since June 3 when unidentified armed men seized him while he was driving in the town. According to a joint submission to the GNU in July by two United Nations special rapporteurs and the Working Group on Enforced Disappearances, the Internal Security Agency (ISA) in Ajdabiya had previously harassed al-Maghribi and subjected him to intimidation. ISA agents in December 2020 and in February had summoned him for questioning on his civil society work, and in April the ISA briefly arrested him for “promoting foreign agendas.” As of October, the GNU had yet to respond.

Women’s Rights, Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity

Libyan law does not specifically criminalize domestic violence. Corporal punishment of children remains common. Libya’s Family Code discriminates against women with respect to marriage, divorce, and inheritance.

The penal code allows for a reduced sentence for a man who kills or injures his wife or another female relative because he suspects her of extramarital sexual relations. Under the penal code, rapists can escape prosecution if they marry their victim. The 2010 nationality law stipulates that only Libyan men can pass on Libyan nationality to their children.

Online violence against women has reportedly grown steadily in recent years, often escalating to physical attacks, with no laws in place to combat the problem.

The penal code prohibits all sexual acts outside marriage, including consensual same-sex relations, and punishes them with flogging and up to five years in prison.

Internally Displaced Persons

As of October, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimated there were 212,593 internally displaced people in Libya, or 42,506 families, with the largest number in Benghazi, followed by Tripoli and then Misrata.

They include many of the 48,000 former residents of the town of Tawergha, who were driven out by anti-Gaddafi groups from Misrata in 2011. Despite reconciliation agreements with Misrata authorities, massive and deliberate destruction of the town and its infrastructure and the scarcity of public services by consecutive interim governments have been the main deterrent for the vast majority to return to their homes.

Migrants, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers

Between January and September, at least 46,626 people arrived in Italy and Malta via the Central Mediterranean Route, most of whom had departed from Libya, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which said arrivals in Malta and Italy in 2021 had been consistently higher when compared with the same period in 2019 or 2020. The organization recorded 1,118 deaths off the shores of Libya between January and September 30.

The IOM identified 610,128 migrants in Libya as of October. According to the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, over 41,000 including more than 15,000 children were registered asylum seekers and refugees as of October. Between January and September, UNHCR assisted 345 vulnerable refugees and asylum seekers to depart Libya, and more than 1,000 refugees and asylum seekers had been identified as a priority for humanitarian evacuations.

The European Union continued to collaborate with abusive Libyan Coast Guard forces, providing speedboats, training, and other support to intercept and return thousands of people to Libya. As of October, 27,551 people were disembarked in Libya after the LCG intercepted them, according to UNHCR.

Migrants, asylum seekers and refugees were arbitrarily detained in inhumane conditions in facilities run by the GNA’s Interior Ministry and in “warehouses” run by smugglers and traffickers, where they were subjected to forced labor, torture and other ill-treatment, extortion, and sexual assault. At least 5,000 were held in official detention centers in Libya as of August, according to IOM.

In June, Doctors Without Borders (MSF) reported that its staff had witnessed shooting by guards in one facility as well as repeated incidents of ill-treatment, physical abuse, and violence in two migrant detention centers in Tripoli, in Al-Mabani and Abu Salim, leading MSF to temporarily withdraw from these centers.

On October 1, authorities conducted raids in Hay al-Andalous municipality in Tripoli on houses and other shelters used by migrants and asylum seekers to curb irregular migration, arresting 5,152 people including women and children, according to IOM. One man was reportedly killed and 15 people injured during the raids. On October 8, during a riot in al-Mabani prison in Tripoli that resulted in a mass break-out of thousands of detainees, guards shot to death at least six migrants and injured at least 24, according to the IOM. As of October, thousands remained in front of the closed UNHCR headquarters in Tripoli protesting conditions and demanding shelter and evacuations outside of Libya.

UNHCR resumed resettlements of refugees and humanitarian evacuations to Niger as of November 3.

Key International Actors

The UN Sanctions Committee’s Panel of Experts report from March found that all Libyan parties as well as Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Syrian Arab Republic, Russia and Turkey had violated the arms embargo. The panel said “violations are extensive, blatant and with complete disregard for the sanctions measures. Their control of the entire supply chain complicates detection, disruption or interdiction.”

In March, the European Union put on its sanctions list the brothers Mohammed and Abderrahim al-Kani, and their Kaniyat Militia, for extrajudicial killings and disappearances in the town of Tarhouna between 2015 and 2020. Mohamed al-Kani was reportedly killed during a raid by armed men on his dwelling in Benghazi in July. In April, the EU lifted sanctions against Khalifa Ghwell, a former prime minister. In June, the EU extended for two years the mandate of the European Integrated Border Management Assistance Mission in Libya (EUBAM Libya), tasked with assisting Libyan authorities in border management, law enforcement and criminal justice.

In June high representatives, including from Germany, the UN, Egypt, France, Italy, Russia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, the United States, and the European Union, convened for the Second Berlin Conference on Libya, which aimed to ensure implementation of the previously negotiated political roadmap and ceasefire agreement. Among the conclusions was a call on Libyan authorities to conduct judicial reviews of all detainees and the immediate release of all those unlawfully or arbitrarily detained.

US Congress in October passed two amendments to the National Defense Authorization Act for 2022 requiring the president to review violations of the Libya arms embargo for sanctions per Executive Order, and another requiring the US Department of State to report on war crimes and torture committed by US citizens in Libya. Hiftar is believed to hold US citizenship.

UN Security Council in October added Osama al-Kuni Ibrahim to the Libya sanctions list in his capacity as de facto manager of the Al-Nasr Migrant Detention Center in Zawiya for directly engaging in, or providing support to commit acts that violate international humanitarian law and human rights abuses. Violations include torture, sexual and gender-based violence, and human trafficking.