For two decades, President Isaias Afewerki of Eritrea used the absence of peace with Ethiopia to justify authoritarianism. The July 2018 peace agreement between the two countries, which ended Eritrea’s diplomatic isolation, have not, as hoped, ushered in an era of respect for human rights in one of the world’s most repressive nations.

The government continued to conscript Eritreans indefinitely into the military or civil service for low pay, with no say in their profession or work location, and often under abusive conditions. The government continued to detain scores of Eritreans without trial, in extremely punitive conditions, and often incommunicado. There is no evidence that the habeas corpus provisions of the new penal code have been implemented.

There was no opening up of civil society space during the year. Independent media outlets inside Eritrea have been shut down since 2001. The government has not scheduled elections or implemented the 1997 constitution guaranteeing civil rights and including limits on executive power. The government nationalized religious schools and closed Catholic health facilities.

Eritrea’s election as a member of the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) beginning in January has not led to greater respect of international standards or engagement with the HRC’s procedures. Instead, Eritrea continues to deny access to the special rapporteur for Eritrea and all other human rights monitors. Despite strenuous opposition by Eritrea, the special rapporteur’s mandate was renewed in July.

Eritrea’s abuses, especially indefinite national service, continue to drive thousands of Eritreans into exile, many of them children. By the end of 2018, 507,300 Eritreans had fled, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), about 10 percent of the population.

Indefinite Military Service and Forced Labor

Most men and unmarried women are forced into open-ended service for the government despite a government decree limiting service to 18 months. After military training, some conscripts are assigned to military duties, but according to the government, over 80 percent are assigned jobs in the civil service or at government agricultural or construction projects. Some conscripts have been forced to work on projects developing infrastructure for foreign mining companies.

Conscripts are subject to inhuman and degrading punishment, including torture, without recourse. Although the government has increased gross pay for certain national service conscripts since 2015, deductions and currency controls make conscript salaries inadequate to meet living costs, much less support a family. Conscientious objection is not recognized and punished. The procedures resulting in discharge from national service are incoherent and opaque.

Legally, conscription begins at 18, but children are among those caught during roundups (“giffas”) in urban areas and sent directly into military service.

Right to Education

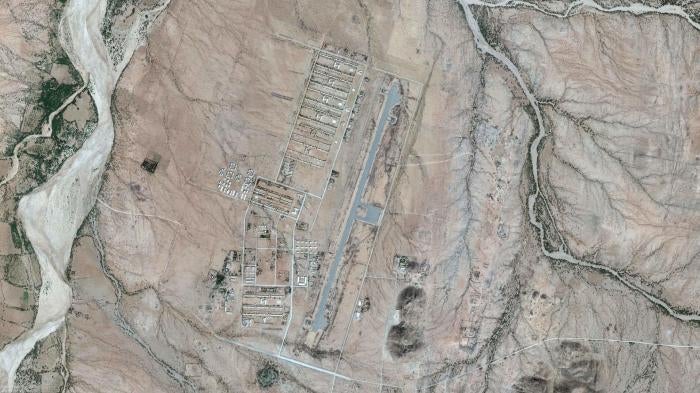

Secondary school students, some aged 16 or 17, are forced to undergo their final school-year, Grade 12, in an abusive military camp, Sawa, where they undergo mandatory military training, are under military command, and take their final school examinations before being assigned to civilian or military duties. Despite calls for reform, in August the government again conscripted the latest batch of students into national service.

At Sawa, military officials subject students to inhumane and degrading punishment. Girls and women students risk sexual harassment and exploitation. On weekends, students are assigned to forced labor at a nearby government farm.

Despite government commitments to reforming the education sector, the government relies on national service conscripts to teach in schools across the country. Conscripts have little to no choice in their assignment and no end to their deployment in sight. Absenteeism is rampant and the education system suffers.

Freedom of Religion

The government continued to “recognize” only four religious denominations as legitimate: Sunni Islam, Eritrean Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Evangelical (Lutheran) churches.

Eritreans affiliated with “unrecognized” faiths risk raids on their homes, imprisonment, and torture; release requires written renunciation of religious affiliation. In 2019, as in previous years, there were reports of raids in Keren and Asmara.

Jehovah’s Witnesses have been especially victimized since 1991 when they refused to participate in the referendum on independence. Fifty-two reportedly remain in prolonged detention at the Mai Serwa prison, including three arrested in 1994 because of their conscientious objections to military service.

The government further restricted activities of the four religions it recognized. In September, it seized control of seven religion-affiliated schools—Catholic, Islamic, and Lutheran. In June, the government confiscated all Catholic health clinics, and expelled patients receiving treatment and resident nuns. The UN special rapporteur on Eritrea expressed concern that their seizure “will negatively impact the right to health of the affected populations, in particular, those in remote rural areas.” The crackdown came after the country’s Catholic bishops released a pastoral letter obliquely calling for justice and reform from the government, and raising alarm about the ongoing exodus from the country.

The government has run the Eritrean Orthodox Church, the nation’s largest religious institution, since it deposed its patriarch, Abune Antonios, in 2007 and placed him under house arrest. In July, media reported that five of the church’s six bishops voted to expel the Abune from the church, accusing him of heresy after he released a video complaining that the church was being led by a government-appointed layman. The expulsion letter threatens punishment for mentioning his name. Five priests were reportedly arrested in June for supporting Antonios.

Unlawful, Abusive Detentions

Eritreans are subject to arrest and incarceration for long periods, without trial or opportunity to appeal. Imprisonment is frequent in vastly overcrowded cells or in shipping containers. Ill-treatment is common, including torture.

The former finance minister and critic of the president, Berhane Abrehe, remains in incommunicado detention since September 2018. His wife, Almaz Habtemariam, arrested earlier in 2018, was released in August.

Many detainees, including government officials and journalists arrested in 2001 after they questioned Isaias’s leadership, are held incommunicado in places unknown to family members. Ciham Ali Abdu, daughter of a former information minister, has been held in incommunicado detention for six years since her arrest at age 15.

Some families only hear of the fate of their imprisoned relatives when the prisoners’ bodies are returned to them. The body of an executive committee member of the Al Diaa school, whose proposed government takeover sparked protests, was returned shortly after his death in January.

The judicial system, partly staffed by national service conscripts subject to military control, has no independence. No public defense lawyers exist.

Freedom of Speech, Expression and Association

Independent press has not been tolerated inside Eritrea since 2001. The Committee to Protect Journalists found that Eritrea was the world’s most censored country and the sub-Saharan African country with the highest number of journalists behind bars. Internet cafes are monitored and, in May, media reported that the government briefly shut down the internet altogether.

No opposition political parties are allowed. Labor unions are also banned, except those controlled by the government, as are gatherings of more than three people. There are no independent nongovernmental organizations. Same-sex relations are prohibited.

Leaving the country without permission is illegal and individuals trying to flee risk being shot, killed, or arrested. For a time after the border to Ethiopia opened in 2018, the government did not restrict departures. At the end of 2018 and again in April 2019, however, the government unilaterally closed several border crossings and reinstated the exit permit requirements. After the Eritrea-Ethiopia border opened, the number of fleeing Eritreans, especially unaccompanied children and women, increased. Hundreds were reported to flee daily in early 2019. Among those fleeing in 2019 were five members of Eritrea’s youth soccer team participating in a regional tournament in Uganda.

Key International Actors

Despite the 2018 rapprochement between Eritrea and Ethiopia, the disputed border has not been demarcated and Ethiopia has not withdrawn from Badme, the village that triggered the 1998 war.

Tensions with Djibouti remain unresolved because Djibouti claims that Eritrea has not accounted for prisoners of war captured in a 2008 border dispute. In 2019, Djibouti requested binding international arbitration; the request remained pending at time of writing.

The International Monetary Fund said Eritrea’s macro-economic conditions remained “dire.” Eritrea was identified in a 2019 survey as one of only three countries that place “extreme constraints” on humanitarian assistance to citizens from international organizations.

Except for a massive 50 percent Australian company-owned potash development project scheduled to begin operations in two to three years, Chinese firms have acquired all mineral mining rights. All mining firms must use government construction firms, staffed largely with conscript labor.

The European Union initiated what it dubbed a dual track approach to Eritrea, with its development arm focusing on job creation activities, and its political arm reportedly raising human rights issues. In February, under its Trust Fund for Africa aimed at stemming migration, the EU provided EUR€20 million (US$22 million) to support the procurement of equipment on a road building project on which it acknowledges national service labor, i.e., forced labor, may be used. In April, a Dutch NGO filed a summons calling on the EU to halt the project or risk further legal challenges.

The EU held two rounds of political dialogue with Eritrea under article 8 of the “Cotonou Agreement,” one in November, the other in March.