Clashes with the Islamic State (also known as ISIS) intensified in 2016, including operations to retake Ramadi in February and Fallujah in June, and the beginning of operations in October to retake Mosul, where fighting displaced over 45,000 Iraqis as of November 11. Credible allegations emerged of summary executions, beatings of men in custody, enforced disappearances, and mutilation of corpses by government forces during the operation in Fallujah.

ISIS executed hundreds in and around Mosul, and used civilians there as human shields.

According to the United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq (UNAMI), since January 2016 airstrikes, explosions, gunfire, or suicide attacks killed at least 9,153 Iraqis. A 2016 International Federation of Journalists report deemed Iraq the deadliest country in the world for journalists and a UNICEF report deemed it one of the deadliest for children.

ISIS Abuses

A joint UNAMI and Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) report from January said that ISIS had kidnapped between 800 and 900 children in Mosul for religious and military training.

ISIS carried out over a dozen suicide and car bombings throughout 2016. In its deadliest attack on July 3 a car bombing in Baghdad killed over 200 people and injuring hundreds more. On July 7, ISIS carried out a triple suicide attack on a Shia shrine in Balad, 100 km north of Baghdad, killing at least 35 and wounding over 60.

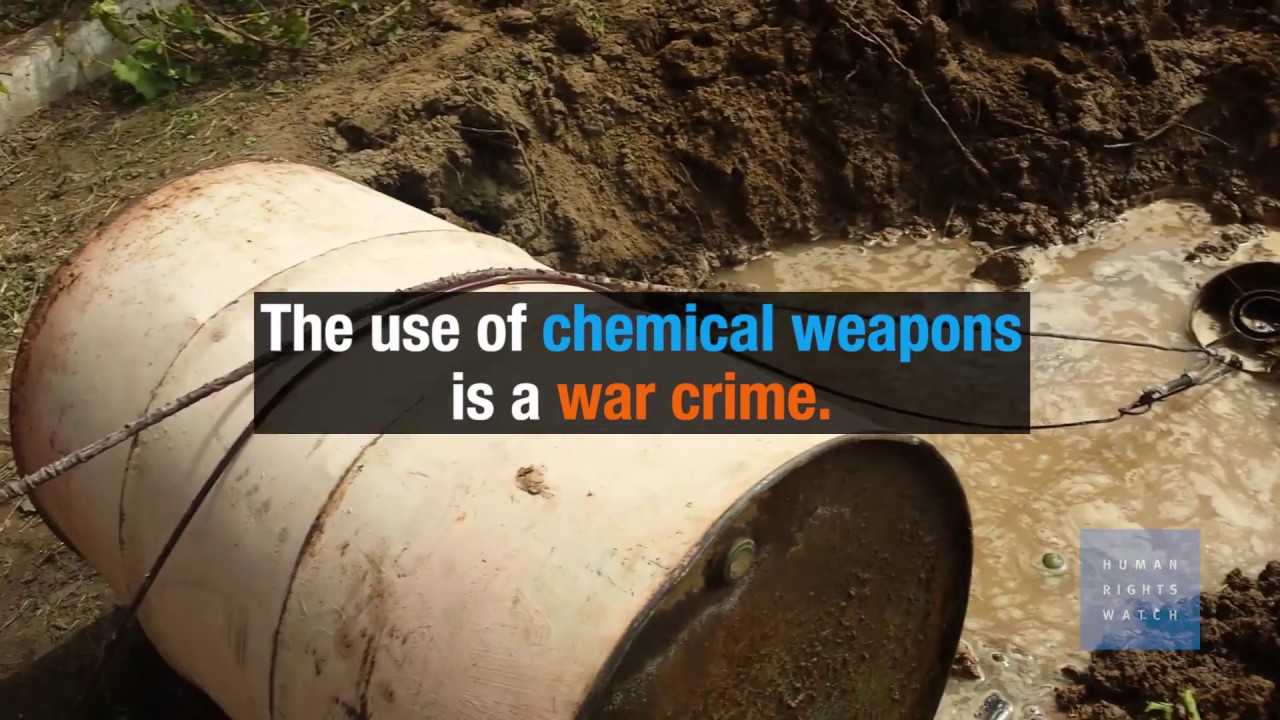

In September and October, ISIS launched at least three chemical attacks on the Iraqi town of Qayyarah, south of Mosul. The use of toxic chemicals as a means of warfare is a serious threat to civilians and combatants and is a war crime.

As the operation to retake Mosul began, ISIS started forcibly evacuating civilians under their control with its fighters apparently using them as human shields.

There were regular, but for the most part unconfirmed, media reports during the year of executions carried out by ISIS. In November, in Hammam al-Alil, 30 kilometers southeast of Mosul, authorities discovered an ISIS mass grave containing the remains of between 50 and 100 bodies. As the battle for Mosul intensified, Human Rights Watch received reports of ISIS carrying out hundreds of executions of former Iraqi Security Forces in territory still under their control.

ISIS’s Diwan al-Hisba (Moral Policing Administration) and online media apparatuses have publicly announced 27 executions of allegedly gay men, at least nine of them in Iraq. The main method ISIS used to execute these men has been to throw them off the roofs of high-rise buildings.

Women and girls reported severe restrictions on their clothing and freedom of movement in ISIS-controlled areas. They told Human Rights Watch that they were only allowed to leave their houses dressed in full face veil (niqab) and accompanied by a close male relative. These rules, enforced by beating or fines on male family members or both, isolated women from family, friends, and public life.

They also reported restricted access to health care or education because of discriminatory ISIS policies, including rules limiting male doctors from touching, seeing, or being alone with female patients. In more rural areas ISIS has banned girls from attending school. ISIS fighters and female ISIS “morality police” hit, bit, or poked women with metal prongs to keep them in line, making them afraid to try to get services they needed.

ISIS also continues to torture, rape, murder, and sexually enslave Yezidi women and children, many of whom were captured in Iraq and taken to Syria. According to a June United Nations commission of inquiry report, ISIS still holds about 3,200 Yezidi women and children, most of whom are in Syria. Such abuses are war crimes and may amount to crimes against humanity, and possibly genocide.

Abuses by Government Forces

On May 24 Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi stated that the government would take measures to protect civilians during the operation to retake Fallujah from ISIS. Nevertheless, the next day an airstrike on Fallujah General Hospital damaged the emergency room. Over the next two weeks of fighting Human Rights Watch documented summary executions, beatings of men in custody, enforced disappearances, and mutilation of corpses by government forces.

As of mid-November, according to local officials, there were still at least 643 men and boys missing, and possibly as many as 800. They said they believed that at least 49 others had been summarily executed or tortured to death while in the custody of Hezbollah Brigade, a prominent group within the government-affiliated Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF).

On June 4, 2016, Prime Minister al-Abadi announced that he had ordered an investigation into allegations of abuse in the Fallujah operations and three days later announced an unspecified number of arrests. Government officials, however, at time of writing had not responded to requests for further information about the status of the investigation, who is conducting it, or steps taken so far.

In August, authorities implemented al-Abadi’s Office Order 91 from February, making the PMF an “independent military formation” within Iraq’s security forces.

Despite government assurances that only the Iraqi Security Forces would screen the thousands of civilians fleeing Mosul for possible ISIS affiliation, on at least one occasion a Shabak militia, part of the PMF, arbitrarily detained men after screening hundreds of families. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and Iraqi authorities have in some cases detained men and boys for weeks arbitrarily as part of the screening process. In many cases, families of detainees did not know where they were being held, for how long, or why.

During the Mosul operation, tribal militias unlawfully detained and mistreated residents of areas retaken from ISIS.

Displacement and Movement Restrictions

Since 2014 and over the course of 2016, Human Rights Watch has documented a pattern of unlawful destruction of Arab homes and sometimes of entire Arab villages, in tandem with the deportation of residents, in areas of Kirkuk and Nineveh governorates where there was no imperative military necessity for such measures. The destruction of homes in many cases amounted to a war crime. Authorities have not allowed internally displaced people to freely move in the Kurdistan region of Iraq and the disputed territories, requiring internally displaced people to stay in camps with severe restrictions on their movement.

Freedom of Media

A 2016 International Federation of Journalists report deemed Iraq the deadliest country in the world for journalists—with more than 300 journalists killed between 1990 and 2015. In August, journalist Wedad Hussein Ali, who was allegedly affiliated with the armed Turkey-based Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), was abducted and killed in Dohuk. KRG Asayish forces had repeatedly interrogated him over the previous 12 months about his writings critical of Kurdish authorities.

In addition to these killings, authorities continue to limit press freedom. In March, Iraq’s specialized Media and Publishing Court summoned al-Alam al-Jadeed’s website editor, Mountadar Nasser, for questioning over a story published a month earlier which accused a regulatory telecommunication committee of corruption. Ultimately the court acquitted Nasser and dropped the defamation charges brought against him.

Also in March, the Iraqi Communications and Media Commission shut down the Cairo-based, privately owned al-Baghdadia TV. A month later, the commission withdrew Qatar-based Al Jazeera’s operating license for 2016, because of “media rhetoric that incites sectarianism and violence.”

Women’s Rights, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Identity

Many of the Yezidi women and girls who escaped ISIS and are displaced in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq lack adequate access to mental health and psychosocial services. Although some services have been provided for women who became pregnant during their captivity, safe and legal abortion services are not available. Iraqi law allows abortion only in cases of medical necessity such as a risk to a mother’s life but not in cases of rape.

Women have few legal provisions and protection mechanisms to shield them from domestic violence. Iraq’s penal code includes provisions on physical assault, but it lacks any explicit mention of domestic violence. While sexual assault is criminalized, article 398 provides that such charges will be dropped if the assailant marries the victim. A 2010 United Nations factsheet stated that one in five Iraqi women were subject to domestic violence, and a 2012 Ministry of Planning study found that at least 36 percent of married women have experienced some form of abuse at the hands of their husbands.

In 2015, Iraqi officials published a draft law on protection against domestic violence that parliament has yet to pass. The law has serious flaws, among others that it prioritizes reconciliation over justice for abuse victims and does not stipulate crimes of domestic violence nor adequate penalties. The law does not set out duties for police and prosecutors to respond to domestic violence, and does not provide for long-term protection for the victims.

Iraq’s penal code does not prohibit same-sex intimacy, although article 394 makes it illegal to engage in extra-marital sexual relations. Due to the fact that the law does not expressly allow same-sex marriage, it effectively prohibits all same-sex relations. In July Moqtada al-Sadr, the prominent Shia opposition cleric, stated that although same-sex relationships are not acceptable, individuals who do not conform to gender norms suffer from “psychological problems,” and should not be attacked.

Children in War Zones

In a June report UNICEF warned that Iraq was “one of the most dangerous places in the world for children,” with 3.6 million children at risk of death, injury, sexual violence, and exploitation.

In March, when Fallujah was still under the control of ISIS, a medical source at Fallujah General Hospital said that starving children were gathering at the local hospital, as there were no more food sources available and families were left eating flat bread made from ground seeds and soup made from grass.

UNICEF estimated that the number of Iraqi children working had doubled since 1990, to more than 575,000.

In 2016, Iraqi government-backed tribal militias, known as Hashad al-Asha’ri, recruited at least 10 children from the Debaga IDP camp in Erbil governorate to fight against ISIS.

Death Penalty

Iraqi courts continued to impose the death penalty. In 2016, there were at least 63 confirmed executions. In late August 2016, Iraqi authorities executed 36 men convicted in a sham group trial for participating in the 2014 ISIS execution of between 560 and 770 Shia army recruits stationed at Camp Speicher, outside Tikrit.

Key International Actors

A US-led coalition of states including Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom carried out over 9,000 airstrikes on ISIS targets since late 2014.

The United States was the largest provider of equipment to the Iraqi military, and Germany the largest provider to the KRG’s Peshmerga forces.

In September, the US deployed an additional 615 US troops, bringing the total number of US troops stationed there to at least 5,180, in order to assist in the operation to retake Mosul.

Lebanon’s Hezbollah group and Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps–Al-Quds Force sent forces into combat in Iraq against ISIS.

Since 2015, the Turkish airforce has carried out airstrikes on PKK positions in northern Iraq. In 2016, Turkish groundtroops entered northern Iraq and attacked ISIS positions near Mosul.