“I don't care about human rights," Rodrigo Duterte boasted in August 2016, shortly after becoming president of the Philippines. In just a few months since coming to power, Duterte’s self-proclaimed anti-drug campaign has resulted in police and “unidentified gunmen” killing thousands of Filipinos, without any semblance of due process. Promising medals to those who join his effort, Duterte has compared himself to Hitler and declared that he would be “happy to slaughter” the more than 3 million Filipinos he describes as “drug addicts.”

This kind of braggadocio makes it difficult to try to change Duterte’s actions by simply showing how his tactics violate basic human rights. In this, he is not alone. Groups like the Islamic State (ISIS), autocrats like Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, and populists vying for political influence in Europe and the United States are distinguishable from one another in many important ways, but they all share a common feature with Duterte: a public embrace of policies that flout international human rights law.

“Naming and shaming,” an important tool for human rights advocacy, works best if advocates can raise the reputational costs of problematic behavior by disclosing that their targets are breaking the rules or highlighting the devastating impact of their actions. But increasingly it seems that some actors are almost completely immune to this kind of pressure. The “shameless” do not seek to hide their abuses or the policies that underpin them, but instead flaunt them as electoral or recruitment tools.

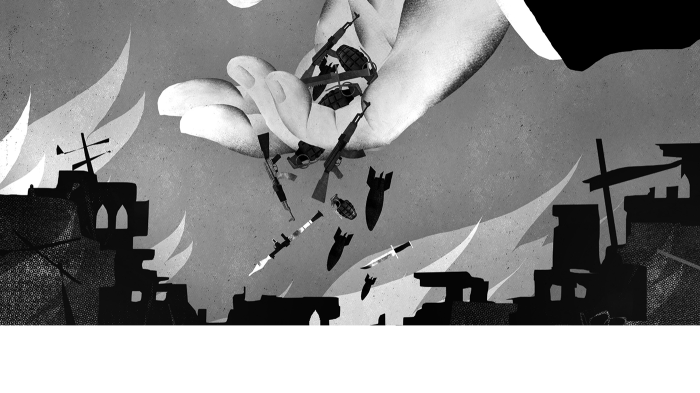

This essay outlines strategies to challenge those actors by shifting the focus from them onto their networks of financial enablers and, for those implicated in violations in armed conflicts or security operations, their arms suppliers. By underscoring their enablers’ complicity in abuses and seeking to impose punitive measures on these enablers directly, human rights advocates have a chance to affect the calculations of the shameless too. Some of those financing or arming abusers may be more vulnerable to being exposed publicly than their clients.

But since enabling alone can amount to a serious international crime or human rights abuse, advocates should also make clear that coercive tools like sanctions and punitive measures like prosecutions apply directly to enablers as well.

The Special Court for Sierra Leone, for example, convicted Liberian president Charles Taylor in 2012 for aiding and abetting the war crimes of a brutal rebel group in neighboring Sierra Leone. The court pointed to Taylor’s role in providing arms and assistance to the abusive Revolutionary United Front (RUF) and his participation in the blood diamond trade, which helped to fund the RUF during Sierra Leone’s armed conflict. More recently, US government lawyers weighing the risks of assisting the Saudi-led coalition in its aerial bombardment of Yemen, are reported to have considered the legal precedent set by the Taylor decision when evaluating their own role as enablers.

Of course, like all advocacy strategies, these tactics need to be calibrated to address the scale and nature of abuses being perpetrated and the degree to which enablers are complicit. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. But focusing on the networks of the complicit, instead of just frontline abusers or their commanders, offers an important vehicle to protect and promote rights.

“Naming and Shaming”

Human rights advocates are adept at leveraging shame to press for change. Once exposed, governments or corporations can become so ashamed to be in the spotlight they quickly switch tactics to avoid further criticism.

For example, within days of an October 2016 report on his government’s role in the rape and sexual exploitation of women and girls displaced by Boko Haram, Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari ordered a special investigation into the allegations. Similarly, the Central African Republic government’s June 2016 decision to suspend the director of an abusive police unit came after researchers documented his role in at least 18 unlawful executions.

Sometimes condemnation or abusers’ fears of prosecution secure rights advocates a seat at the table to define how policy makers should remedy the situation. Extensive research on the use of child labor in mining, for example, has given advocates an opportunity to shape the due diligence guidance promulgated by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development for responsible investment. In Japan, research on the harassment and bullying of youth based on their sexual orientation and gender identity laid the foundation for a push to revise the country’s national curriculum to be more inclusive of the needs and perspectives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students.

Counterintuitively, the energy that some abusive governments devote to silencing critics, even as they continue to commit abuses, also reveals that naming and shaming has power.

Bahraini human rights defender Nabeel Rajab, for example, faces up to 15 years in prison for his tweets about alleged torture in Jau prison and airstrikes by the Saudi-led coalition, of which Bahrain is part, in Yemen. And in June 2016, days after the United Nations added the Saudi-led coalition to its “list of shame” for attacking schools, and hospitals, and killing and maiming children in Yemen, Saudi Arabia and its Arab allies launched an unprecedented diplomatic campaign to get off the roster, including by threatening to stop funding key humanitarian programs. While UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon made this blackmail public, leaving the Saudi-led coalition with a diplomatic black eye, the campaign worked. Powerful abusers can often evade criticism, even when it is based on well-documented patterns of abuse.

More worrying is the fact that some abusers attempt to draw power from public attention to their abuses. When ISIS broadcasts its executions, it covers the faces of its fighters, but not their acts. This is not accidental. ISIS seems to have designed its fighters’ rape of Yezidi women in Iraq and the brutality of its rule in Libya in part as a magnet for recruits. A recent UN report on ISIS concluded: “By publicizing its brutality, the so-called ISIS seeks to convey its authority over its areas of control, to show its strength to attract recruits and to threaten any […] that challenge its ideology.”

There are many other less egregious cases where the same principle applies. Australia’s offshore detention processing centers for asylum seekers seem to be designed to be so inhumane that they dissuade others from seeking refuge on its shores.

In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orban is not shy of publicly advancing policies that violate basic norms. He emphasizes, “European identity is rooted in Christianity” and points to the so-called “right to decide that we do not want a large number of Muslim people.” Orban’s government erected razor-wire fences and prosecuted asylum seekers who bypassed them. It purposely stoked anti-refugee sentiment by spending millions of taxpayers’ money on a smear campaign to bolster a referendum to reject a binding EU duty to relocate asylum seekers to Hungary from overstretched Greece and Italy. These policies may appear to be aimed at keeping asylum seekers and migrants away but they also mobilize popular support for the government.

During Donald Trump’s campaign for the US presidency, he openly urged policies that would amount to war crimes under international humanitarian law. For example, he repeatedly lauded the benefits of waterboarding and “worse,” dismissing those who disapprove of using such techniques as “too politically correct.” When reminded that torture is illegal, Trump promised that he would work to change the law. Governing, of course, is different than campaigning. Following his election, Trump told “60 Minutes” and the New York Times that torture “is not going to make the kind of a difference that a lot of people are thinking.”

Rhetoric like this is hugely problematic. Trump’s focus on whether the tactic is effective misses the point. International law makes it clear that that no national emergency, however dire, ever justifies torture. Further, Trump’s choice of retired Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn as his National Security Advisor demonstrates a disturbing disregard for human rights principles and the laws of war since, even when asked directly, Flynn did not repudiate proposals such as waterboarding that would constitute torture.

For many populist politicians, publicity of their tactics or condemnation as being abusive is not seen as something to avoid. Instead, it is viewed as an effective deterrence strategy and an electoral argument. These governments justify harsh policies that violate rights as necessary to counterterrorism or stem migration and dismiss rights groups’ criticism by pointing to the broad-based popular support of their citizens. Indeed, leaders need followers and any comprehensive strategy to address the enablers of shameless leaders should consider how and why these messages resonate with voters, recruits and supporters.

Similarly, it is also worth considering the role of allied governments in offering shameless abusers political cover and protection from scrutiny at inter-governmental bodies, like the UN. Russia, for example, has used its power as a permanent member of the UN Security Council to cast five vetoes to shield the Assad government’s crimes in Syria.

Confronting Enablers

Naming and shaming has limits when dealing with the shameless. But that does not mean that these actors are untouchable or unmovable. While condemnation in the press or public may not restrain them or change their calculations, these actors do not operate in a vacuum. In regions with effective regional human rights courts like the European Court of Human Rights, litigation can offer an important vehicle for redress. But in many other regions, to effectively confront the shameless, advocates must look beyond shining a spotlight on what abusers are doing wrong. Human rights groups need to shift some of their focus onto those who are enabling these shameless actors to continue that wrongdoing.

A dynamic whole-systems approach, which confronts enablers, is not uncharted territory. In 1997, advocates seeking to end the abuses of Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), an armed group founded in northern Uganda that also reveled in its own brutality, appealed to the government of neighboring Sudan to end its support for the group. In 2003, researchers connected the weapons being used in unlawful attacks by Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) to neighboring Guinea. Pointing to these ties, which flouted a UN arms embargo on Liberia, Human Rights Watch called for a suspension of US military assistance to Guinea.

Efforts to challenge the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam’s (LTTE) use of child soldiers did not stop at Sri Lanka’s borders. In 2006, Human Rights Watch examined coercive practices the LTTE used to extract money from the Tamil diaspora in Canada. While urging the Canadian government to take steps to end that intimidation and extortion, the report also recommended that the diaspora itself seek to ensure that funds provided for humanitarian causes not be used to benefit the LTTE while it committed serious abuses.

This research strategy involved showing both that the tactics being used to extract money in Canada were abusive and that the funds themselves helped to further abuses back in Sri Lanka. The Canadian government and others subsequently prohibited LTTE fundraising on their soil. Almost a decade later, a Court of Appeals in The Hague found that five people who had raised millions of euros for the LTTE were part of a criminal organization with the intent of committing war crimes, including recruiting child soldiers. In this case, the enablers were not just exposed, they were also convicted for their role as a part of the broader “criminal organization.”

Research in 2013 on abuses by armed groups in their offensive to take parts of Latakia province in Syria—dubbed “Operation to Liberate the Coast”—took this approach a step further. Researchers used social media postings to identify individuals who actively raised funds to support the operation. Unlike previous work on the LTTE, this research did not unearth any evidence of coercion or abusive tactics to extract money. Unlike the situation involving the LURD, there is no arms embargo on Syria. Nonetheless, by pointing to the abuses being conducted by groups financed by those donations, Human Rights Watch suggested restricting or blocking money transfers from Gulf residents to groups responsible for the operation. Noting that funders were potentially liable for the group’s abuses if they continued to provide money after the operation’s abusive tactics became public, this advocacy strategy emphasized that enablers were at risk of complicity.

Financiers of Abuses

Drawing on research into ISIS crimes in Libya, Human Rights Watch has called on the UN Security Council to impose sanctions, not just on ISIS and its members but also “those who intentionally finance or otherwise assist abuses.” This recommendation is grounded in the idea that sanctions on those knowingly financing abuses might stop them from continuing to enable these atrocities.

Of course, even before human rights groups made this recommendation, global efforts to curb the spread of ISIS were already seeking to choke its financial networks. Similar tactics have been used to respond to North Korea and Iran’s nuclear programs.

Some of these inter-government initiatives are motivated by policy considerations that go far beyond the scope of human rights organizations work and mandates. Others straddle both arenas. The UN Security Council’s many sanctions committee panels of experts have long held mandates that included a duty to research and identify those responsible for human rights abuses and war crimes, and to investigate arms sales, the illegal exploitation of natural resources and finances.

Human rights research typically does not extend to doing the painstaking financial forensic analysis required to identify those financiers and enablers. Venturing into this area will require harnessing the research expertise of accountants, arms experts, and others who specialize in mapping these networks, and learning from effective techniques that others are using to target networks that support shameless perpetrators. For example, The Sentry, a new initiative led by George Clooney and John Prendergast seeking to explore this space, follows the money and then makes policy recommendations that seek to alter the incentive structures that let enablers benefit financially and politically from abusive conflict and mass atrocities in east Africa.

But even if human rights groups can successfully harness this expertise, there is no guarantee of success. For example, the 2015-2016 ISIS attacks in France cost relatively little, just tens of thousands of euros. The Bastille Day attack on Nice cost Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel no more than €2,700. Still, in some cases, adopting a wider lens could provide important leverage for those seeking to change the behavior of shameless abusers.

One example of the potential opened by adopting this wider lens is recent work applying the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights to violations of international law in the West Bank. In its January 2016 report, Human Rights Watch concluded that it is impossible to do business in Israeli settlement communities without contributing to injustice and discrimination against Palestinians. Rights campaigners have long engaged with companies to ask them to voluntarily stop their activities in settlements and screen their supply chains for settlement-related activities. Based on a business and human rights analysis, Human Rights Watch was able to join them in arguing, for example, that by advertising, selling, and renting homes in settlements, the Israeli franchise of the real estate company RE/MAX contravenes best practices for corporate social responsibility and its responsibilities to uphold human rights.

One lesson from this kind of work is the importance of piercing the veil of plausible deniability. Human rights groups have an important role to play here by informing corporations of their possible complicity in distant abuses and war crimes.

In June 2015, the Swiss government prosecutor declined to move forward with a case brought by TRIAL International, an NGO that fights against impunity for international crimes, against a Swiss gold refiner for its role in processing conflict-affected gold from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Charges that the refiner had unlawfully abetted a pillaging Congolese armed group were dropped because the prosecution did not find evidence that the refinery knew enough about abuses happening at the gold’s real point of origin. If evidence had been available that the refiner was notified about abuses and proceeded with business anyway, this kind of a defense, based on ignorance of complicity, would not have been valid.

The use of tools of coercion like targeted sanctions or asset freezes inevitably raises questions about unintended consequences, possible violations of due process, and mistaken identity. These risks are heightened because enforcement actions frequently occur without any kind of legal proceeding. There are also legitimate concerns about the proportionality of these measures, particularly considering the impact that these sanctions can have on family members and business partners of sanctioned individuals and entities.

Some sanctions mechanisms, like the ones established by the UN Security Council to combat terrorism, now include a means to appeal these measures, but the appeals process remains deeply flawed. Outside the counterterrorism realm, other sanctions regimes enforced by the UN Security Council do not even have those limited safeguards.

Additionally, fear of penalties for violating sanctions restrictions can lead international businesses to aggressive de-risking, where they simply stop doing business in “high risk” jurisdictions. This can unintentionally marginalize communities by limiting their access to financial services, preventing them from accessing critical remittances and atrophying their economic development. Oxfam has campaigned against the US government’s restrictions, for example, on informal money transfers to Somalia, pointing to the impact it had on Somalis access to the remittances they rely on to meet their basic needs.

There is a human rights case for caution, but also one for thoughtful sanctions enforcement against enablers who aid and abet or are knowingly complicit in abuses. These measures can play a powerful role in influencing behavior and should always be reversible, giving enablers who focus on their bottom line a reason to stop supporting abusers. Finding ways to effectively freeze assets of enablers while not giving short shrift to due process and other fundamental rights is a challenge. However, it is one that human rights advocates should see as part of their work.

Arms Suppliers

Financial backers play a role in enabling the shameless, but for those conducting abusive military campaigns in Syria, South Sudan, or Yemen, arms suppliers remain among their most important enablers.

Although not impossible, it is much more difficult to continue to commit abuses on a large scale without the influx of new weapons and ammunition, either from abroad or through domestic production. Many human rights groups’ mandates do not extend to stopping wars, which conflicts with a policy of neutrality in all armed conflicts. Instead, advocates push for hostilities, when they occur, to be conducted according to international humanitarian law.

Nonetheless, in places like Syria, rights advocates have argued the UN Security Council to impose arms embargoes to stop further sales and transfers of weapons to known abusers and war criminals. In 2016, following years of advocacy at the UN by arms control, humanitarian, and human rights groups, the Security Council considered a resolution that would have imposed an arms embargo and limit future weapons transfers to South Sudan. In the US, rights advocates campaigned against a US$1.2 billion arms sale to Saudi Arabia pushing the US Congress to debate and vote on the issue in September 2016. In the United Kingdom, the Campaign Against Arms Trade brought a lawsuit challenging the export licensing of weapons sales to Saudi Arabia in light of abuses being committed by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen.

In November 2016, Turkey decided to gradually stop sales and production of fertilizer, despite its many legitimate uses in agriculture, due to concerns about terrorism. The decision came after brisk cross-border fertilizer sales from Turkey to Syria triggered speculation that ISIS was using the fertilizer to build explosives.

In places where police or law enforcement are responsible for widespread abuses, like the Philippines, Burundi, or Egypt, rights groups have worried that bilateral donor assistance, especially to the security sector, could be contributing to abuses. In March 2015, in the wake of heavy criticism from human rights groups for resuming weapons sales to the Sisi government in Egypt, the US decided to wind down its longstanding policy of allowing the Egyptians to buy US equipment on credit starting in FY2018.

In June 2016, the UN peacekeeping mission in the Central African Republic decided to stop accepting Burundian police due to concerns about “serious and ongoing” human rights violations by police back in Burundi. The Burundian government, like many developing countries, benefits from the salaries paid to their troops and participating in UN missions. In November 2016, the US State Department suspended a planned sale of 26,000 assault rifles to Duterte’s Philippines following an objection raised by US Senator Ben Cardin about Duterte’s abusive “war on drugs.”

Since 2012, human rights groups have pointed to the role of Russia’s state-owned arms dealer, Rosoboronexport, in selling the Syrian government weapons and urged responsible governments and corporate actors to avoid all new business dealings with the company. Campaigners have also asked arms fairs in Paris and London to stop featuring Rosoboronexport as an exhibitor.

Human rights groups have also directly challenged UK-based BAE Systems and the US-based Boeing and General Dynamics for their role in supplying Saudi Arabia with weapons that enable abuses in Yemen. BAE is currently engaged in discussions around a possible five-year contract to supply Saudi Arabia with Eurofighter Typhoon combat aircraft. The recent arms sale to Saudi Arabia approved by the US Congress included Abrams tanks produced by General Dynamics to replace tanks that had been damaged as a part of combat operations in Yemen.

In August 2016, Textron, the last company manufacturing cluster munitions in the United States, decided to end its involvement in that business. Shame created by the international ban on these weapons did not achieve this victory alone. Mounting concerns over civilian casualties from the use of the weapons by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen were instrumental. The company’s own explanation of its decision to stop producing cluster munitions came on the heels of the US government’s May suspension of cluster munitions sales to Saudi Arabia and made clear that it had become “difficult to obtain approvals” needed for its sales to foreign customers.

But those more conventional tools are not the only paths to halt the flow of weapons into places where they may be used to commit further abuses. In 2012, the UK invoked EU sanctions to stop the delivery of repaired attack helicopters to the Syrian government by calling on the ship’s British insurer, Standard Club, to revoke its coverage of the vessel. Although an insurance company is not the first entity that comes to mind when thinking about the arms trade, by looking beyond the usual suspects, the UK was able to turn the ship around before it could deliver its cargo. Pushing the insurance company to stop its coverage of the ship due to its cargo’s problematic destination required treating them as a complicit enabler.

More recently, in October 2016, NATO’s secretary general warned Spain against allowing Russian warships headed for Syria to refuel in its ports. By cautioning that the ships could “be used as a platform for more attacks against Aleppo and Syria, and thereby exacerbating the humanitarian catastrophe,” NATO raised the reputational stakes for the Spanish government. Although Spain did not formally rescind the permission to dock, the Spanish chose to request a clarification from Russia about the nature of their mission in light of ongoing abuses in Syria. Shortly after, Malta made clear that it was unwilling to let Russian ships stop and refuel in their ports either.

Focusing on the Complicit

One of the more frustrating moments human rights advocates face is when perpetrators issue denials. The Sudanese minister who refuses to believe that his government’s troops could use chemical weapons or rape hundreds of Darfuri women, or the Chinese Communist Party official who called the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 “much ado about nothing” are paradigmatic examples.

Blanket denials of months or even years of painstaking research are an everyday hazard of human rights work. But the shameless do not even bother with denials of this kind. They revel in being criticized. For human rights advocates and those who fight to civilize the conduct of war, these shameless actors pose an undeniable threat. Responding will require expanding the frontiers for human rights advocacy.

Human rights research typically focuses on those who have blood on their hands or should have used their power and authority to prevent injustice. But in situations where exposing abuses alone is not enough to effect change, advocates need to consistently adopt a wider lens and devote more energy to better understanding the expansive networks of financial backers and arms suppliers who enable abusers to continue their wrongdoing. That kind of analysis may require more specialized expertise that falls outside of human rights documentation. But it is worth the investment.