Morocco’s 2011 constitution incorporated strong human rights provisions, but these reforms have not led to improved practices, the passage of significant implementing legislation, or the revision of repressive laws. In 2014, Moroccans exercised their right to peaceful protest in the streets, but police continued to violently disperse them on occasion. Laws that criminalize acts deemed harmful to the king, the monarchy, Islam, or Morocco’s claim over Western Sahara limited the rights to peaceful expression, assembly, and association. Courts continued to convict and imprison street protesters and dissidents in unfair trials. On a more positive note, Morocco implemented reforms announced in 2013 to its policies on migrants, granting temporary legal status to hundreds of refugees and to thousands of other foreigners, most of them sub-Saharan.

Freedom of Expression

Independent print and online media continue to investigate and criticize government officials and policies, but face prosecution and harassment if they step too far. The press law mandates prison terms for “maliciously” spreading “false information” that authorities consider likely to disturb the public order, or for speech that is ruled defamatory.

Moroccan state television allows some space for debate and investigative reporting but little for direct criticism of the government or dissent on key issues. Authorities pursued their investigation on terrorism charges of Ali Anouzla, director of the independent news site Lakome.com, because of an article describing, and providing an indirect link to, a jihadist recruitment video. In 2013, Anouzla spent five weeks in detention after publishing the article.

Rapper Mouad Belghouat (“El-Haqed”), whose songs denounce corruption and police abuse, spent four months in prison after being convicted on charges of assaulting police officers, in a trial where the judge refused to summon any defense witnesses or purported victims. Authorities in February prevented a Casablanca bookstore from hosting an event for El-Haqed’s new song album. Seventeen-year-old rapper Othmane Atiq (“Mr. Crazy”) served a three-month prison term for insulting the police and inciting drug use for his music videos depicting the lives of disaffected urban youth.

Abdessamad Haydour, a student, continued to serve a three -year prison term for insulting the king by calling him a “dog,” “a murderer,” and “a dictator” in a YouTube video. A court sentenced him in February 2012 under a penal code provision criminalizing “insults to the king.”

Freedom of Assembly

Authorities tolerated numerous marches and rallies to demand political reform and protest government actions, but they forcibly dispersed some gatherings, assaulting protesters. In Western Sahara, authorities prohibited all public gatherings deemed hostile to Morocco’s contested rule over that territory, dispatching large numbers of police who blocked access to demonstration venues and often forcibly dispersed Sahrawis seeking to assemble.

On April 6, police arrested 11 young men at a pro-reform march in Casablanca and accused them of hitting and insulting the police. A court of first instance on May 22 sentenced nine of them to prison terms of up to one year and two to suspended sentences using similarly worded “confessions” police said they had made in pretrial detention, although the defendants repudiated them in court. On June 17, the court provisionally freed the nine pending the outcome of their appeals trial, which was continuing at time of writing.

Freedom of Association

Officials continue to arbitrarily prevent or impede many associations from obtaining legal registration although the 2011 constitution guarantees the right to form an association. In May, authorities refused to register Freedom Now, a new free speech group and prohibited it from holding a conference at the bar association in Rabat. Other associations denied legal registration included charitable, cultural, and educational associations whose leadership includes members of al-Adl wal-Ihsan (Justice and Spirituality), a nationwide movement that advocates for an Islamic state and questions the king's spiritual authority.

In Western Sahara, authorities withheld recognition for all local human rights organizations whose leaders support independence for that territory, even those that won administrative court rulings that they had wrongfully been denied recognition.

Authorities also prohibited tens of public and non-public activities prepared by legally recognized human rights associations, such as an international youth camp that the national chapter of Amnesty International had organized every summer; and numerous conferences, training sessions, and youth activities organized by the Moroccan Association for Human Rights (AMDH) and its branches.

Between April and October, Morocco expelled at least 40 foreign visitors from Western Sahara. Most of those affected were either European supporters of Sahrawi self-determination or freelance journalists or researchers who had not coordinated their visit with authorities. These expulsions, along with heavy Moroccan police surveillance of foreigners who did visit and met Sahrawi rights activists, undermined Morocco’s efforts to showcase the Western Sahara as a place open to international scrutiny.

Police Conduct, Torture, and the Criminal Justice System

Legal reforms advanced slowly. A law promulgated in September empowers the newly created Constitutional Court to block proposed legislation if it contravenes the new constitution, including its human rights provisions. A proposed law that would deny military courts jurisdiction over civilians was awaiting parliamentary approval.

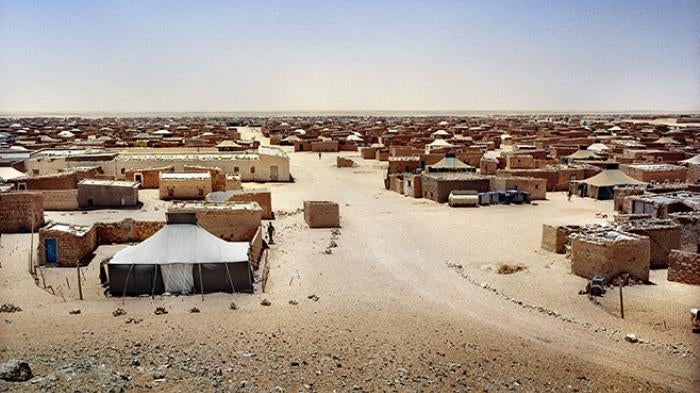

Meanwhile, military courts continued to try civilians, including Mbarek Daoudi, a Sahrawi activist held since September 2013, on weapons charges. Twenty-two other Sahrawis remained in prison serving long sentences imposed by a military court in 2013. The men had been charged in connection with violence that erupted on November 8, 2010, when authorities dismantled the Gdeim Izik protest camp in Western Sahara. Eleven members of the security forces were killed in the violence. The military court failed to investigate defendants’ allegations that police officers had tortured or coerced them into signing false statements, and relied heavily on the statements to return its guilty verdict.

Courts failed to uphold the right of defendants to receive fair trials in political and security-related cases. Authorities continued to imprison hundreds of suspected Islamist militants they arrested in the wake of the Casablanca bombings of May 2003. Many were serving sentences imposed after unfair trials following months of secret detention, ill-treatment and, in some cases, torture. Police have arrested hundreds more suspected militants since further terrorist attacks in 2007 and 2011. Courts have convicted and imprisoned many of them on charges of belonging to a “terrorist network” or preparing to join Islamist militants fighting in Iraq or elsewhere. Morocco’s 2003 counterterrorism law contains a broad definition of “terrorism” and allows for up to 12 days of garde à vue (pre-charge) detention.

After visiting Morocco and Western Sahara in December 2013, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) concluded, “The Moroccan criminal judicial system relies heavily on confessions as the main evidence to support conviction. Complaints received by the Working Group indicate the use of torture by State officials to obtain evidence or confessions during initial questioning ….Courts and prosecutors do not comply with their obligation to initiate an ex officio investigation whenever there are reasonable grounds to believe that a confession has been obtained through the use of torture and ill-treatment.” The WGAD said authorities had allowed it to visit the places of detention it had requested, and to interview detainees of its choice in private.

Moroccan courts continue to impose the death penalty, but authorities have not carried out executions since the early 1990s.

Prison conditions are reportedly harsh, largely due to overcrowding, exacerbated by the proclivity of investigating judges to order the pretrial detention of suspects. The National Human Rights Council (CNDH), which urged the government to expand alternative punishments, reported that the prison population had reached 72,000 in 2013, 42 percent of them pretrial, with an average of 2 square meters of space per inmate. The CNDH is a state-funded body that reports to the king.

A court on August 12 sentenced left-wing activist Wafae Charaf to serve one year in prison and pay a fine, and damages for slander and “falsely” reporting an offense, after she filed a complaint after unknown men abducted and tortured her following a workers’ protest in April in Tangiers. An appeals court in that city on October 20 doubled her prison term to two years. A Casablanca court sentenced one local activist to three years in prison, a fine, and damages, on the same charges, after he reported having been abducted and tortured by unknown men. The sentences in these two cases could have a chilling effect on people wishing to file complaints of abuse by the security forces.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Moroccan courts continued to jail persons for homosexual behavior under article 489 of the penal code, which prohibits “lewd or unnatural acts with an individual of the same sex.” Two of six men arrested in Beni Mellal in April and charged under this provision received prison terms for this and other offenses.

On October 2, a court sentenced a British tourist and a Moroccan acquaintance to four months in prison for homosexuality. After spending about three weeks in jail, the two men were released pending appeal.

Migrants and Refugees

Implementation continued of a 2013 plan to overhaul national policies toward migrants. Morocco’s refugee agency granted one-year renewable residency permits to more than 500 UNHCR-recognized refugees. At time of writing, Morocco had not determined the status it would grant to more than 1,300 Syrians, whom UNHCR recognizes as refugees. Morocco also granted one-year renewable residency permits to thousands of sub-Saharan migrants who were not asylum-seekers but who met certain criteria. However, security forces continued to use excessive force on migrants, especially the mostly sub-Saharan migrants who were camping near, or attempting to scale, the fences separating Morocco from the Spanish enclave of Melilla (see also Spain chapter).

Rights of Women and Girls

The 2011 constitution guarantees equality for women, “while respecting the provisions of the Constitution, and the laws and permanent characteristics of the Kingdom.” In January, Parliament removed from article 475 of the penal code a clause that had, in effect, allowed some men to escape prosecution for raping a minor if they agreed to marry her. The code retains other discriminatory provisions, including article 490, which criminalizes consensual sex between unmarried people and so places rape victims at risk of prosecution if the accused rapist is acquitted.

The Family Code discriminates against women with regard to inheritance and the right of husbands to unilaterally divorce their wives. Reforms to the code in 2004 improved women’s rights in divorce and child custody, and raised the age of marriage from 15 to 18. However, judges routinely allow girls to marry below this age. In September 2014, the Committee on the Rights of the Child expressed concern that Morocco had not adopted a legislation criminalizing all forms of domestic violence, including marital rape, although violence against women and girls in the home is reported to be pervasive.

Domestic Workers

Despite laws prohibiting the employment of children under the age of 15, thousands of children under that age—predominantly girls—are believed to work as domestic workers. According to the UN, nongovernmental organizations, and government sources, the number of child domestic workers has declined in recent years, but girls as young as 8 years old continue to work in private homes for up to 12 hours a day for as little as US$11 per month. In some cases, employers beat and verbally abused the girls, denied them an education, and refused them adequate food. In January 2014, an Agadir court sentenced an employer to 20 years in prison for violence leading to the death of a child domestic worker in her employ. In September 2014, the Committee on the Rights of the Child expressed concern that the government had not taken effective measures to remove children from hazardous domestic labor.

Morocco’s labor law excludes domestic workers from its protections, which include a minimum wage, limits to work hours, and a weekly rest day. In 2006, authorities presented a draft law to regulate domestic work and reinforce existing prohibitions on domestic workers under 15 years old. The draft had been modified but not adopted at time of writing.

Key International Actors

France, a close ally and Morocco’s leading trading partner, refrained from publicly criticizing human rights violations in the kingdom. Morocco suspended its bilateral judicial cooperation agreements with France in February after a French investigating judge served subpoenas on a visiting Moroccan police commander based on a complaint of complicity in torture. The United States is also a close ally of Morocco. Secretary of State John Kerry, in Rabat in April for the bilateral “Strategic Dialogue,” avoided any public mention of human rights concerns.

The government in recent years has granted access to several UN human rights mechanisms seeking to visit Morocco and Western Sahara, including the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention in December 2013 (see above). Then-UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay, on an official visit on May 29, noted Morocco’s “great strides towards the better promotion and protection of human rights,” but cited several areas of concern, including torture, restraints on freedom of expression, and the need to implement laws guaranteeing rights set out in the 2011 constitution.

As in past years, the UN Security Council in April renewed the mandate of UN peacekeeping forces in Western Sahara (MINURSO) without broadening it to include human rights monitoring, something Morocco strongly opposes.