Executive Summary

If someone escapes hell, how can you grab them and take them back to hell?

– Bamba, a 31-year-old from Ivory Coast who reached Italy in October 2016

Soft-spoken Abdul left Darfur in 2016 when he was eighteen. He went to Egypt, where he registered with the UN refugee agency UNHCR but, despairing of being resettled, Abdul decided to go to Libya to attempt the journey to safety in Europe. He spent three months in a smuggler warehouse in Sebratha but there too he endured “very much suffering,” and escaped to Tripoli. It would only be in early May 2018 that, in the early hours of the morning, he finally crammed himself into a rubber boat with over 100 people and set off from Khoms, a coastal city east of Tripoli. Their journey was short; the Libyan Coast Guard intercepted the rubber boat after roughly four hours at sea.

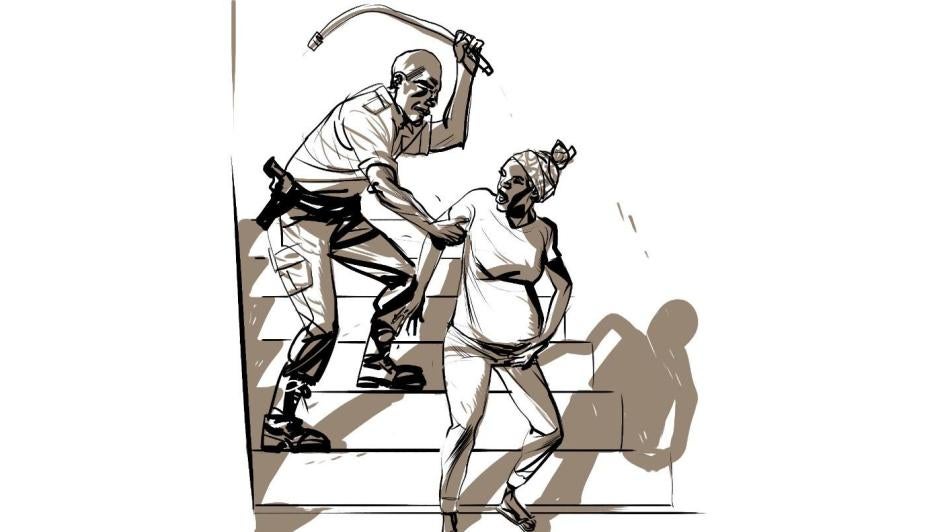

When we spoke in mid-July, he was recovering from what he described as torture by the guards in al-Karareem detention center near Misrata, where he had been detained in abysmal, overcrowded and unsanitary conditions for two months. He said guards beat him on the bottom of his feet with a hose to make him confess to helping three men escape. Abdul’s hopes were thread-bare; he wished only to be transferred to a detention center in Tripoli, where he hoped he would have more access to UN agencies that might help him.

Abdul’s experience encapsulates the struggle, dashed hopes, and suffering of so many migrants and asylum seekers in Libya today: beholden to unscrupulous smugglers, captive to a market that exploits the most basic human needs for survival and dignity, victims of indifference or downright hostility to people in need of protection and safety.

In July 2018, Human Rights Watch researchers visited four detention centers in Tripoli, Misrata, and Zuwara where they documented inhumane conditions that included severe overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, poor quality food and water that has led to malnutrition, lack of adequate healthcare, and disturbing accounts of violence by guards, including beatings, whippings, and use of electric shocks.

Migrant children are as much at risk as adults of being detained in Libya. Human Rights Watch witnessed large numbers of children, including newborns, detained in grossly unsuitable conditions in Ain Zara, Tajoura and Misrata detention centers. They and their caretakers, including breast-feeding mothers, lack adequate nourishment. Healthcare for children, as for adults, is absent or severely insufficient. There are no regular, organized activities for children, play areas or any kind of schooling. Almost 20 percent of those who reached Europe by sea from Libya in the first nine months of 2018 were children under the age of 18. Children are also not exempt from abuses; we documented allegations of rape and beatings of children by guards and smugglers.

Because it is indefinite and not subject to judicial review, immigration detention in Libya is arbitrary under international law.

Senior EU officials are aware of the plight facing migrants detained in Libya. In November 2017, EU migration commissioner, Dimitri Avramopoulos, said, “We are all conscious of the appalling and degrading conditions in which some migrants are held in Libya.” He and other senior EU officials have repeatedly asserted that the EU wants to improve conditions in Libyan detention in recognition of grave and widespread abuses. However, Human Rights Watch interviews with detainees, detention center staff, Libyan officials, and humanitarian actors revealed that EU efforts to improve conditions and treatment in official detention centers have had a negligible impact.

Instead, European Union (EU) migration cooperation with Libya is contributing to a cycle of extreme abuse. The EU is providing support to the Libyan Coast Guard to enable it to intercept migrants and asylum seekers at sea after which they take them back to Libya to arbitrary detention, where they face inhuman and degrading conditions and the risk of torture, sexual violence, extortion, and forced labor.

Since 2016, the EU has intensified efforts to prevent boat departures from Libya. EU policy-makers and leaders justify this focus as a political and practical necessity to assert control over Europe’s external borders and “break the business model of smugglers,” as well as a humanitarian imperative to prevent dangerous boat migration. In reality, the externalization approach has the effect of avoiding the legal responsibilities that arise when migrants and asylum seekers reach EU territory by outsourcing migration control.

EU institutions and member states have poured millions of euros into programs to beef up the capacity of the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord—one of two competing authorities in Libya, and one whose power rests largely on fungible alliances with militias and no real control over territory—to intercept boats leaving Libya and detain those intercepted in detention centers where they face appalling conditions. Italy—the EU country where the majority of migrants departing Libya arrive—has taken the lead in providing material and technical assistance to the Libyan Coast Guard and abdicated virtually all responsibility for coordination of rescue operations at sea in a bid to limit the number of people arriving on its shores.

Legal and bureaucratic obstacles have blocked most nongovernmental rescue operations in the central Mediterranean. While Mediterranean departures have decreased since mid-2017, the chances of dying in waters off the coast of Libya significantly increased from 1 in 42 in 2017 to 1 in 18 in 2018, according to UNHCR.

Clashes in Tripoli between competing armed groups in August-September 2018, which lasted for a month, presented further problems and risks for detained migrants. During the clashes—which illustrated the Government of National Accord’s fragile hold on power and caused civilian deaths and destruction to civilian structures—guards abandoned at least two detention centers as fighting drew near, leaving detainees unprotected inside. Authorities eventually transferred hundreds to other detention centers in the capital, contributing to even greater overcrowding in those centers. The fighting also temporarily interrupted EU-funded humanitarian aid to the detention centers and United Nations programs to evacuate vulnerable asylum seekers and repatriate migrants.

Since the end of 2017, the UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), also a UN agency, have accelerated EU-funded programs to help asylum seekers and migrants safely leave Libya, a country with no refugee law and no asylum system. By the end of November 2018, UNHCR had evacuated 2,069 asylum seekers from Libya to a transit center in Niamey, Niger, for refugee status determination and, ultimately, resettlement to Europe and other countries. However, the program suffers from UNHCR’s limited capacity and mandate in Libya as well as from a gap between the number of resettlement places host countries are prepared to offer and the number of refugees in need. As of November 2018, UNHCR also evacuated an additional 312 directly to Italy and 95 to a UNHCR emergency transit center in Romania.

The IOM had assisted over 30,000 to return from Libya to their home countries through its “voluntary humanitarian program” between January 2017 and November 2018. While the program can be valuable in assisting people without protection needs who wish to return home safely, it cannot be described as truly voluntary as long as the only alternatives are the prospect of indefinite abusive detention in Libya or a dangerous and expensive journey across the Mediterranean.

Despite these programs, increased interceptions by the EU-supported Libyan Coast Guard led to an increase in the number of migrants and asylum seekers detained in Libya. At the time of our research, in July 2018, there were between 8,000-10,000 people in official detention centers, up from 5,200 in April 2018.

The cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment in Libyan detention centers described in this report violate international law. Libyan authorities are accountable for these abuses and the lack of accountability for perpetrators. EU institutions are aware of the mistreatment and inhumane detention conditions in Libya for those intercepted. Indeed, the EU provides support intended to ameliorate these conditions in detention. However, even though that support has had minimal impact on the situation, the EU continues to pursue a flawed strategy to empower Libyan Coast Guards to intercept migrants and asylum seekers and take them back to Libya. Where the EU, Italy and other governments have knowingly contributed significantly to the abuses of detainees, they have been complicit in those abuses.

Neither the complexities of international migration nor the myriad challenges facing Libya today excuse the brutality visited in Libya upon migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees.

Key Recommendations

- Libyan authorities should end arbitrary immigration detention and institute alternatives to detention, allow UNHCR to operate in full respect of its mandate, improve conditions in detention centers, and ensure accountability for state and non-state actors who violate the rights of migrants and asylum seekers;

- EU institutions and member states should ensure and enable robust search-and-rescue operations in the central Mediterranean, significantly increase resettlement of asylum seekers and vulnerable migrants out of Libya, and impose clear benchmarks for improvements in Libyan search-and-rescue capacity as well as treatment and conditions in detention centers in Libya, and be prepared to suspend cooperation if benchmarks are not met;

- United Nations agencies should press for respect by EU and Libyan authorities of the rights of migrants and asylum seekers in Libya and should increase coordination amongst themselves and with Libyan authorities to ensure that people with protection needs, including children, are properly identified, tracked, and protected.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report in Libya from July 4 to July 12, 2018. Although we requested from the Government of National Accord (GNA) Interior Ministry access to all Directorate for Illegal Migration (DCIM) managed facilities in western Libya, DCIM granted access only to four immigration detention centers in Ain Zara, Tajoura, Zuwara and Misrata. All interviews with detainees were conducted privately and out of earshot of guards. Center staff did not determine whom we spoke with. Guards were able to see but not hear us as we conducted interviews. One interviewee who escaped a few weeks after our visit told us a guard pressed him to relate our questions and what he had told us.

We conducted 66 individual interviews with migrants and asylum seekers, and seven group interviews with a total of 41 persons. We spoke with 33 women, 66 men, 4 unaccompanied girls aged 8-17, and 4 unaccompanied boys aged 13-16. Group interviews provided information about the situation in the center, information specific to a group of the same nationality, and shared experiences of arrests or interceptions at sea. Almost all of the detailed individual accounts came from one-on-one interviews, though some group interviews allowed for specific details on individuals in the groups. The interviews were conducted in English, French, and Arabic. Interviewees were from Bangladesh, Cameroon, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ivory Coast, Mali, Morocco, Nigeria, Palestine, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan (Darfur), and Syria.

In every detention center visited, Human Rights Watch met with the director and other senior staff. Human Rights Watch met with the head of the DCIM, senior officials in the GNA Libyan Coast Guard, including the commander and spokesperson, and the heads of mission for the International Organization for Migration and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, as well as staff of international nongovernmental organizations. Human Rights Watch met also with representatives of the EU’s Border Assistance Mission in Libya (EUBAM) and the Italian ambassador to Libya at the time.

Human Rights Watch sent letters detailing our findings and requesting comment to DCIM head Brigadier General Mohamed Bishr, Italian Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister Matteo Salvini, EU Council President Donald Tusk, EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Federica Mogherini, EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, and a representative of the International Maritime Organization. We did not receive any replies in time for inclusion in the report. Human Rights Watch also put questions to the IOM and UNHCR; their responses are reflected in the report.

This report also contains evidence obtained from interviews conducted in Italy in 2016 with migrants and asylum seekers and on board an NGO rescue ship in 2017.

All names of migrant, refugee, and asylum seeker interviewees have been changed for their protection. In all cases, Human Rights Watch told interviewees they would receive no personal service or benefit for their statements and that the interviews were completely voluntary.

Human Rights Watch decided to brief the director of DCIM at the end of the research mission, on issues of ill treatment and inhumane detention conditions. We did not raise individual cases with detention center staff to protect detainees from possible retaliation.

In accordance with international standards, all interviewees under the age of 18 are considered children.

This report only covers detention activities and EU cooperation in western Libya and does not cover the detention regime and coast guard activities in eastern Libya carried out by forces affiliated with the Libyan National Army (LNA) and the Interim Government. While the European Union and EU member states back only the Tripoli-based GNA and do not formally have ties with the rival government in the east, some countries, including Italy, the United Kingdom and France, conduct meetings with General Khalifa Hiftar, the commander of the LNA.

I. Migrants, Asylum Seekers, and Refugees in Libya

Libya has long been a destination for migrants seeking work as well as a transit country for migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees seeking to reach the EU.[1] Estimates of how many are in Libya vary significantly. In addition to the 8,000-10,000 migrants and asylum seekers in official detention at the time of our visit, the United Nations estimates that more than 680,000 migrants and asylum seekers live in Libya outside detention; while an unknown number are held in warehouses and other informal detention centers operated by smuggling networks and militias.[2] Within its severely constrained scope of action (see below), the UN refugee agency UNHCR had registered 55,912 asylum seekers and refugees in Libya, primarily from Syria, Iraq, and Eritrea, as of mid-October 2018.[3]

Following the uprising and armed conflict in 2011 that led to the fall of Muammar Gaddafi’s 42-year government, there was a short period of respite before another wave of violence in 2014 overtook much of the country. This led to the collapse of central authority and emergence initially of three, now two, separate authorities competing for legitimacy. The ongoing political turmoil and protracted armed conflicts since 2014 have plunged the country into an economic crisis in which illicit smuggling, including of human beings, has flourished. People smuggling and trafficking is now a multi-million-euro business in the country, a major source of livelihood for many Libyans.[4]

Two governments vie for legitimacy and control of the country. The United Nations Security Council and the European Union recognize the Government of National Accord (GNA), based in the capital Tripoli, in the west, but not the rival Interim Government based in the eastern cities of al-Bayda, Tobruk and Benghazi. In various parts of the country militias linked to the interior and defense ministries of the GNA have clashed with those linked to the Libyan National Army (LNA) and the Interim Government. All efforts to achieve political reconciliation have foundered. In Libya’s vast south, a hub for regional smuggling, Tebu, Tuareg and Arab armed groups fight one another for control of territory and resources. The fighting has decimated the country’s economy and public services, including the public health system, law enforcement, and the judiciary.[5] Around 200,000 people remain internally displaced by the conflicts.[6] In western Libya, militias operate checkpoints, police neighborhoods, run prisons and provide security for private corporations such as banks and public institutions including ministries, prisons and migrant detention centers. They are also involved in criminal activities including smuggling and extortion.[7]

Fighting broke out in Tripoli in late August 2018 between armed groups linked to the interior and defense ministries of the GNA. They were competing for control of territory and access to income from vital institutions in the capital. A UN-brokered cease-fire on September 26, 2018, ended the clashes, which claimed the lives of at least 100 people and wounded at least 500, the majority of them civilians.[8] Migrants in at least two detention centers were transferred to other facilities, still in Tripoli, while several hundred were reportedly released from a third. The fighting severely disrupted services provided by NGOs and UN agencies. Because of the insecurity, the humanitarian organization Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) temporarily reduced its staff and medical activities in DCIM centers in Tripoli.[9]

Human Rights Watch has documented abuses by smugglers, militias and criminal gangs against migrants in Libya for over a decade., including rapes, beatings and killings, kidnapping for ransom, sexual exploitation, and forced labor. [10] In Libya in July, Kameela, a 23-year-old Somali woman detained in Ain Zara detention center, told us she and her husband were held by smugglers somewhere in southern Libya, along with roughly 400 others, for three months in late 2017 and early 2018. She said she was repeatedly raped. “A big man there, a Libyan, he raped me. My husband couldn’t stop him, they held a gun to his head. Every night he did this to me. If I said, ‘don’t touch me,’ he beat me.” At the time we spoke, Kameela was seven months pregnant. She said the pregnancy was the result of the rape.[11]

Many migrants who contract smugglers willingly to facilitate their migration journey end up victims of trafficking, defined in international law as the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons through “the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion...or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control of another person, for the purpose of exploitation.”[12]

There is significant evidence that smugglers operate in varying degrees of collusion with government officials and militias. A confidential UN Panel of Experts report on Libya leaked to the press in February 2018 and reviewed by Human Rights Watch concluded that most smuggling and trafficking groups have links to official security institutions. The Panel of Experts expressed concern in the report “over the possible use of state facilities and state funds by armed groups and traffickers to enhance their control of migration routes.”[13] The panel heard accounts of Eritreans who said that the Special Deterrence Force, a militia affiliated with the GNA Interior Ministry, arrested them and then handed them over to smuggling networks.[14] In June 2018, the UN Security Council imposed sanctions on six Libyans accused of human smuggling and trafficking, including Abd al-Rahman al-Milad, the head of the Zawiya coast guard unit, which is affiliated, at least nominally, with the GNA Defense Ministry’s Coast Guard.[15]

In September 2018, the UNHCR reiterated its call on all countries “to allow civilians (Libyan nationals, former habitual residents of Libya and third-country nationals) fleeing Libya access to their territories.” The refugee agency urged all countries to suspend forcible returns to any part of Libya, including anyone rescued or intercepted at sea, and stated that Libya should not be designated as a “safe third country” for the purpose of rejecting asylum applications from people who have transited Libya.[16] UNHCR has not, however, taken a clear position on EU capacity-building programs for the Libyan Coast Guard even though as a matter of policy and practice people intercepted or rescued by these forces are placed in inhuman and degrading detention that is arbitrary by virtue of being prolonged, indefinite and not subject to judicial review.

Detention

Foreigners, regardless of age, without authorization to be in Libya are detained on the basis of laws dating back to the Gaddafi era that criminalize undocumented entry, stay and exit punishable by imprisonment, fines, and forced labor.[17]

Immigration detention in Libya can be indefinite because the law does not specify a maximum term, providing only that detention be followed by deportation. There are no formal procedures in place allowing detainees access to a lawyer or any opportunity to challenge the decision to detain them. Prolonged detention of adults and children other than the period strictly necessary to carry out a lawful deportation and without access to judicial review amounts to arbitrary detention and is prohibited under international law.

Human Rights Watch learned of only one instance where Libyan authorities allegedly freed detainees from immigration detention through a judicial process. In that case, five Palestinians and two Syrians who had been intercepted at sea and detained at Tajoura center were released after paying fines for illegal entry and exit. The director of Tajoura center told Human Rights Watch these individuals later were on board a rescue ship that disembarked in Spain in June 2018.[18]

The Directorate for Illegal Migration (DCIM), under the GNA Interior Ministry, is nominally responsible for operating official detention centers. At the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit, in July 2018, DCIM head Brigadier General Mohamed Bishr said that 8,672 people were detained in 16 centers, up from 5,200 in April.[19] The IOM estimated at the time that there were more than 9,300 migrants and asylum seekers in official detention.[20] The number of official centers fluctuates over time; the logic for opening and closing them can be baffling. While centers are staffed with DCIM personnel, most centers are under the effective control of whichever armed group controls the neighborhood where a center is located.

At the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit, the Ain Zara center was guarded by the militia controlling most of the city of Ain Zara known as Battalion 42, or “al-Sheikh,” after its commander Hakim al-Sheikh. Researchers noted the presence of unmarked armed vehicles parked outside the center and the entry of militia members into the premises. At the Tajoura detention center, a militia known as Katibat al-Dhaman, under command of Mohamed Dreider, is in charge of providing security for the prison complex that houses the DCIM facility and a separate prison under the Justice Ministry. Researchers noted the presence of armed men from the militia within the complex. A unit from the Central Military Region, a GNA-linked armed group predominantly from Misrata, is in charge of security of al-Karareem Facility. Armed men were present within the al-Karareem compound during the visit. At the Zuwara detention center, a militia known as the Zuwara Protection Force, under the Zuwara Military Council, is in charge of providing security for the town including the detention center.

As noted, militias and other armed groups operate an unknown number of unofficial detention centers. One asylum seeker from Darfur told researchers he was held for two weeks in the military camp of Brigade 301, a major Misrata-led and GNA-aligned armed group in Tripoli and was forced to work at no pay.[21] Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) provides medical and humanitarian assistance to migrants and asylum seekers at official detention centers in Libya. In a December 2017 report, the organization explained that “[u]nofficial places of captivity can be taken over and categorized as detention centres overnight, or vice versa…. When new managers or guards take over, the detention regime can change, becoming more or less violent and allowing or barring the provision of services by the UN or NGOs.”[22]

While some of the detainees in DCIM centers were arrested in raids on smuggler camps, private homes, and in stops on the streets, the increase in interceptions at sea by the LCG is swelling numbers at the centers and contributing to greater overcrowding and deteriorating conditions. UNHCR reported a “critical worsening” of conditions, with more rioting and protests as a result.[23] At least 59 out of 107 detainees whom we interviewed in four detention centers in July 2018 said they had been intercepted or rescued by the LCG.

The arbitrary and indefinite nature of the immigration detention system in Libya means there are only discretionary, informal and often dangerous or exploitative ways for people to get out.

Some detainees are released to work in private homes, on farms, or in construction. Some are paid for their labor and then allowed to leave or escape. Human Rights Watch has, however, heard numerous statements of people forced to work for no pay. Issouf, a 31-year-old from Ivory Coast we interviewed aboard an NGO rescue ship in October 2017, was detained briefly in Tajoura detention center in 2016; he got out quickly because he was chosen to do brickwork on a man’s property. “No, no, no, he didn’t pay me. He didn’t let me go; I escaped. You see, you can work and when you’re done they’ll take you back to prison,” Issouf said.[24] Ousmane, a 25-year-old from Mali, also managed to escape after he was taken out of the Abu Salim detention center, where he had been detained for eight months, for work laying bricks.[25] Musa, a 16-year-old detained in the Tajoura facility, told Human Rights Watch, “Sometimes boys can get out to work on a farm. But I don’t want to do that. You work for months and then maybe they sell you to someone else.”[26]

Suleyman, a 30-year-old from Darfur in the Sudan, said he was forced to work without pay for an armed group while he was detained at a DCIM detention center in Tripoli known as Trig el-Matar.

I was taken out of prison to clean streets, institutions and universities, and work at the military camp of Brigade 301, but was not given any money. I stayed for about 14 days and used to sleep inside the military camp [Brigade 301]. I got one meal a day, sometimes not. Some of us demonstrated, so they took one guy, Nasreddin, and shot him in the leg.[27]

Bribing guards or consular officials to secure release is another way out of detention.[28] A 16-year-old boy who reached Italy in 2017 told Human Rights Watch he had paid to get out of Tajoura detention center, then “went straight from prison to the boat.”[29]

Some detainees attempt risky escapes from detention centers. Detainees at Tajoura center told us several men had attempted an escape a few weeks before our visit, and that while a few managed to get away, guards shot at and injured several others. A detainee at the al-Karareem detention center in Misrata said he was tortured after helping three men escape.[30] Human Rights Watch has also heard about collective punishment following escape attempts. The 16-year-old boy mentioned above, for example, said guards at Tajoura center hit “everyone” after a group of detainees tried to escape.

Some representatives of embassies in Tripoli visit detention centers, or conduct Skype interviews with nationals, to facilitate repatriation. The director of Ain Zara center said most detainees, especially Sudanese nationals, refuse to meet with their embassies, though he recalled one occasion in which a Sudanese government representative convinced a group of Sudanese to accept repatriation. According to a released detainee from Palestine, one Palestinian asylum seeker from Gaza who spent 1.5 years at Trig el-Sikka center in Tripoli, was allegedly deported to Egypt and then onward to Gaza.[31]

We also heard of visits by Somali embassy staff to Ain Zara and Tajoura centers, including earlier on the same day that we visited Tajoura. Somalis are among the nine nationalities UNHCR may register as people of concern given a presumption of protection needs; efforts by Somali officials to identify and repatriate nationals raise serious concerns unless the Somali nationals in question have prior access to UNHCR for a determination of any protection needs or risks upon return.

Until October 2017, UNHCR was able to secure the release of particularly vulnerable asylum seekers—primarily women and children as well as critical and urgent medical cases—into their care in Libya; that year 1,428 people were released into the care of the agency.[32] UNHCR Libya told us that since then Libyan authorities have allowed releases to UNHCR only for the purpose of evacuation to a third country.[33] A UNHCR “transit and departure” center in Tripoli that could accommodate up to 1,000 people out of detention centers stood empty for five months until receiving final authorization from Libyan authorities in early December 2018.[34] The center should allow some freedom of movement to asylum seekers living there.

Finally, UNHCR operates a program to evacuate asylum seekers and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) operates a program to repatriate migrants to their countries of origin out of Libyan detention centers. These programs are discussed in the next chapter.

II. EU-Libya Migration Cooperation

Despite instability in Libya, the European Union (EU) has since 2015 deepened its partnership with the GNA on migration control. This cooperation is rooted in the EU’s ambition to outsource responsibility for migration control to countries outside the EU. Since at least 2016, EU policy-makers and leaders have justified this approach as a political and practical necessity to assert control over Europe’s external borders as well as a humanitarian imperative to prevent dangerous boat migration. In June 2018, EU leaders reaffirmed their commitment to “continue and reinforce this policy to prevent a return to the uncontrolled flows of 2015 and to further stem illegal migration on all existing and emerging routes … to stop smugglers operating out of Libya or elsewhere … to definitely break the business model of smugglers, thus preventing the tragic loss of life.”[35]

The approach has the effect of avoiding the legal responsibilities that arise when migrants and asylum seekers reach EU territory, including territorial waters, or otherwise come under EU jurisdiction. EU law and jurisprudence justly affirms the right to seek asylum, the right to fair procedures, and the right to humane treatment.[36]

Political calculations also influence policy choices. Marco Minniti—Italian interior minister under the government of Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni, promoter of closer migration cooperation with Libyan authorities and architect of policies to restrict NGO rescue operations in the Mediterranean—argued that “resigning ourselves to the impossibility of regulating migration flows and giving human traffickers the keys to European democracies is not an alternative, this is the heart of problem.”[37] The proposition that harsher migration policies would syphon support from anti-immigrant parties would prove incorrect: Minniti’s Democratic Party lost badly in national elections in early 2018, and his successor Matteo Salvini, of the anti-immigrant League Party, would subsequently block disembarkation from NGO rescue ships, threaten to take migrants rescued by Italian forces back to Libya in violation of international law, and pursue closer collaboration with Libyan authorities.[38]

Financial aid to Libya is designed both to increase the capacity of Libya’s border control, notably by its Coast Guard, and, in recognition of the human rights issues raised, to address chronic and systemic problems in Libya’s detention regime for migrants. The EU has allocated €266 million from the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa for migration-related programs in Libya, and an additional €20 million through bilateral assistance.[39] EU financial assistance has supported positive efforts including training, improved registration of migrants and asylum seekers, and help getting a limited number of people out of abusive detention. Nevertheless, this funding has not helped to diminish the widespread and systematic violence and abysmal conditions in migrant detention centers.

Support for Libyan Coast Guard

Building the capacity of the Libyan Coast Guard and Navy under the GNA is a central plank in the EU’s containment policy. The EU’s anti-smuggling operation EUNAVFOR MED—also known as Operation Sophia—includes a training program, begun in October 2016, for Libyan Navy and Coast Guard officers, petty officers, and sailors at least nominally under the Libyan Government of National Accord’s Defense Ministry. As of June 2018, 213 Libyan Coast Guard and Navy personnel had participated in training courses, out of 3,385 total personnel.[40] A classified 2018 report from the EU’s Border Assistance Mission in Libya (EUBAM) indicated that LCG staff includes an “unknown number” of former revolutionary fighters who fought to topple Gaddafi in 2011 and who were incorporated into the LCG after 2012. None of them had had any training at all, according to the report.[41]

Italy has taken the lead in EU efforts to build the capacity of Libyan authorities to secure Libya’s borders and patrol the Mediterranean. A former colonial power in Libya, Italy has deep historical, political, and economic ties with the country, and engaged in significant migration cooperation agreements with the Gaddafi government.[42] The majority of migrants and asylum seekers departing Libya reach Italian shores. Successive Italian governments have complained that other EU countries have failed to share responsibility for legal processing and reception of new arrivals and they have responded to the significant increase in arrivals since 2014 with policies focused on stemming the flows, despite negative rights consequences.[43] More than any other EU country, Italy is investing significant material and political resources to enable and legitimize Libyan authorities to intercept and subsequently detain anyone trying to leave the country by sea.

In February 2017, Italy signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the GNA on migration control. Italy has since delivered four patrol boats pursuant to a 2008 agreement and, in August 2018, the Italian parliament voted in favor of a government decree to donate 12 patrol boats to the Libyan Coast Guard, along with €1,370,000 for maintenance of the vessels and training of Coast Guard personnel.[44] As part of this package, the Italian government delivered in October 2018 a 27-meter patrol boat to “to strengthen capacity in border control and fight against illegal trafficking.”[45]

Italy is carrying out an EU-funded project to assist Libya in setting up a maritime rescue coordination center (MRCC), which is expected to be operational in 2020. In the meantime, a Libyan operations room has been set up aboard an Italian Navy ship docked in Tripoli. Colonel Abu Ajeila Ammar, head of the Libyan Coast Guard search-and-rescue operations, told Human Rights Watch, “We coordinate with MRCCs Rome and Malta, and the operations room is there to enhance the cooperation.”[46]

The Libyan Coast Guard does not have capacity to provide continuous coverage or rapid response in every case of distress in the entire area that Libya unilaterally delineated as its search and rescue zone. In a report leaked in March, the EU’s anti-smuggling operation in the Mediterranean, EUNAVFOR MED, cited a “critical infrastructural situation” in the operations room, limited language and software skills among personnel, fuel and equipment shortfalls.[47] Libyan units have inadequate and insufficient boats, chronic maintenance problems, and fuel shortages that limit their ability to patrol even Libyan territorial waters and quickly reach boats in distress, according to information obtained through Human Rights Watch interviews with Libyan Coast Guard commanders in Tripoli and Sebratha in July 2018.[48]

Relying heavily on technical and surveillance assistance from Italy, the LCG increased the number of interceptions in the first half of 2018. The LCG intercepted 12,490 people in the first seven months of 2018, a 41 percent increase over the same period in 2017.[49] By the end of 2018, the LCG had intercepted 15, 235 people according to UNCHR data, a slightly lower number than in the preceding year.[50]

In June 2018, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), a UN inter-governmental organization, acknowledged a vast Libyan SAR region. In a meeting in April 2018 with a senior IMO official , in which Human Rights Watch discussed the evidence of insufficient capacity, reckless and dangerous behavior by Libyan Coast Guard units, allegations of collusion between these forces and smugglers, and the risks faced by migrants and asylum seekers who are returned to Libya, the official argued that coordination among MRCCs was sufficient and that “you can’t make a blanket statement that Libya is not a place of safety” under the terms of existing maritime law.[51] He explained that the IMO’s role was to register declared SAR regions when the declaration is in conformity with IMO stipulations and is agreed to by neighboring states.[52]

Acknowledgment of a Libyan SAR region coincided with implementation of a hardline approach by Italy’s new government, including closing its ports to nongovernmental rescue groups and intensifying its practice, tested since at least May 2017, of transferring responsibility to Libyan Coast Guard forces in international waters even when there are other, better-equipped vessels, including its own patrol boats or Italian Navy vessels, closer to the scene.[53] Uncertainty around rescue coordination and disembarkation, as well as prosecutions, ship seizures and administrative acts to block rescue ships in port, forced nongovernmental rescue groups to suspend rescue operations in the central Mediterranean for months.[54] In late November 2018, three NGOs returned to international waters off Libya to perform search and rescue.[55]

Commercial ships are being called upon to respond to situations of distress and put in the position of having to hand migrants and asylum seekers to Libyan Coast Guard forces at sea or disembark people directly in Libya. In several instances, Italy has instructed commercial ships in the initial phase of a rescue only to hand coordination over to Libyan authorities.[56] The resistance and protests of rescued persons against return to Libya illustrate their fears, well-founded, of being forced back to inhuman and degrading detention.[57] On November 20, 2018, Libyan forces used tear gas and rubber bullets to violently remove around 80 people from the cargo ship Nivin in the port of Misrata, after they had refused to disembark for ten days. Acting on instructions from the Italian MRCC, the Nivin had rescued them in international waters and subsequently docked in Misrata.[58] Observers on the ground estimate that 11 people were injured, and that among them were three people with gunshot wounds from live ammunition. Human Rights Watch was not able to independently confirm this information. While 50 were taken to detention centers, 29 were reportedly imprisoned on criminal charges relating to hijacking and piracy.

A Spanish fishing boat, the Nuestra Madre de Loreto, remained at sea for ten days with 11 people it rescued in international waters late November 2018. The boat’s captain refused to follow instructions, including from the Spanish government, to disembark in a Libyan port. Malta agreed to allow disembarkation on December 2, 2018, on the condition everyone would be subsequently transferred to Spain.

The rate of death per attempted crossing has significantly increased. UNHCR estimated that one in 18 people died or went missing in the period January-July 2018 compared to one in every 42 people in the same period in 2017.[59] The IOM also estimated that the rate of death per attempted crossing has increased from 2.1 percent in 2017 to 3.1 percent in 2018. According to the IOM, there were 20 recorded deaths in April and 11 in May 2018, while an estimated 564 people died or went missing in June 2018.[60] Statistical analysis developed by the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI) on the basis of IOM and UNHCR data demonstrates that the rate of deaths at sea compared to the number of people attempting the voyage rate surged in the absence of NGO rescue patrols from 2.3 percent to 7 percent.[61] An ISPI mapping of major shipwrecks—in which over 15 people died—between June 16-July 31, 2018, indicates that many appear to have taken place in areas patrolled in earlier periods by NGO rescue groups.[62]

Alexandra, 25, mother of two children from Ghana, who had travelled to Libya with her husband Kofi, 32, said they had both been on a boat with 180 people in June and, after the Coast Guard intercepted and disembarked them, they saw dead bodies of migrants:

We were surprised when the Libyan Coast Guard came, we were in the blue sea [a term used by migrants to describe international waters]. There were women and children with us on the boat and water had started to enter the boat we were on. At disembarkation in Khoms port, I saw five dead bodies already there from another ship. They were smelly and there were flies all around. We had to sleep at the port for one night. The bodies of the dead people were not removed for as long as we stayed there.[63]

When interviewed, Alexandra was in detention, as was her husband.

Some interviewees described acts of intimidation or violence by members of the Coast Guard during interceptions. Joanna, 34, from Cameroon and mother of three, said that she was on a boat with 170 people that was already in international waters after 10 hours at sea in early June 2018, when a Coast Guard vessel approached:

Men on the large Libyan boat threw us a rope and at first we refused to tie it to ours. The Libyans shot into the air and threatened us: “If you don’t tie it onto the boat then we will shoot at you.” So we tied it to our boat and they started to move people to their boat.[64]

Ahmed, 26, a Palestinian from Gaza, described a similar incident in May 2018 when the Coast Guard approached the boat he was on after 11 hours at sea, during his second attempt to reach Europe. Ahmed said they were in sight of a large orange-colored ship:

Some people jumped off our boat and started to swim toward the foreign boat.…Two of the three Libyans on board the large rescue ship, one of whom was from the Coast Guard and two who were in military uniform, shot into the water next to where we were. They also came very close to our boat and started to make waves to scare us. People got scared and finally started to board their ship. They took us to Khoms.[65]

This may have been an incident reported by SOS MEDITERRANEE, whose rescue ship the Aquarius is orange and white, on May 7, in which the crew observed people jumping in the water. The rescue group said that the Libyan Coast Guard declined their repeated offers of assistance and ordered the ship to leave the area.[66]

Italy’s then ambassador to Libya, Giuseppe Perrone, told Human Rights Watch that training had led to “significant improvement” in LCG performance. He acknowledged that coast guards were “probably overly aggressive [at times],” but said, “we have confronted the LCG about their aggressive behavior. They are defensive, saying they need to protect migrants when lives are at risk. We are trying to shape a narrative whereby they treat Africans with respect.”[67]

Humanitarian Assistance in Detention Centers

EU institutions and member states have repeatedly declared that they do not fund Libya’s Directorate for Illegal Migration (DCIM) directly, but rather channel all funding to UN agencies and nongovernmental organizations to improve conditions in the centers and provide material and medical assistance to detainees.[68] The Italian government has channeled €2 million through its development agency to seven Italian NGOs to provide assistance to detainees in three detention centers in Tripoli, and has solicited bids for a €4.2 million program in five centers outside Tripoli (Gharyan, Sebratha, Zuwara, Khoms, and Janzour).[69] Programs in detention centers include providing material (mattresses, blankets, clothing), food, hygiene kits for men and women, medical care (including anti-scabies campaigns), and assistance to improve general sanitary conditions.

Staff members of international humanitarian organizations operating in Libya described to Human Rights Watch poor coordination and even disputes among humanitarian actors, including UN agencies, and the lack of a conflict-sensitive framework that requires assessment of the interaction between humanitarian assistance and the conflict context to avoid negative impacts. More broadly, these observers expressed concern that humanitarian assistance to detainees in official detention centers, vital as it may be, served to prop up a system of abusive, arbitrary detention and provide a fig leaf for EU migration control policies.[70] These interlocutors requested anonymity to protect their access to detention centers and relations with Libyan and EU authorities.

IOM and UNHCR staff are authorized to assist disembarkation in 12 official ports along the western coast between Misrata and Zuwara. Each agency is responsible for six disembarkation points, where they provide basic material assistance (hygiene kits), quick medical checks, although not systematically for all who are disembarked, and register basic information about each person, mostly limited to the name and nationality.

Accounts from individuals intercepted by the LCG suggest that these UN agencies are not present at all disembarkations, either because they take place in unofficial locations, remote locations, or during the late hours of the night, or because the agencies are unable to send staff.

Mulugeta, a 27-year-old from Ethiopia who was detained in Zuwara when we interviewed him, said there were no international organizations present when he was disembarked in that city in June 2018. A group of men wearing a mix of uniforms and civilian clothes took all their money and cell phones, and one of them beat Mulugeta when he asked for his possessions, he said. “They made us keep our heads down, there is no way of knowing who hit me.”[71]

Solomon, 20, from Sierra Leone, whose younger brother was among several who drowned during his last attempt to cross to Europe by boat on June 29, said during an interview that upon disembarkation, DCIM staff took all of the people’s phones and that upon arrival at the detention center, they took some people’s money and did not return any of the personal effects.[72]

UN agencies are trying to systematize registration of all migrants at disembarkation points, using electronic tablets to record basic information. Once people are placed in detention, they may be transferred to other centers without proper record-keeping, or leave the center in a variety of ways, including transfer into the hands of smuggling networks, payment of a bribe, removal by militias for forced labor, or escape. Detention centers do not systematically make a record of the name, nationality and age of every person who is transferred into the center. This means DCIM, but also UN agencies and humanitarian organizations present in detention centers, easily lose track of people and are unable to find them again.[73]

In early September 2018, UNHCR issued a press release reporting that smugglers and traffickers were impersonating their staff at disembarkation points as well as other locations.[74] The account of Hawa, a 19-year-old from Mali, of her disembarkation in Khoms in early June suggests there may have been smugglers present. She said she was “sure that some people managed to pay to escape from the port.… They gave us a cell phone to call a Libyan contact to arrange release. I tried to call but then I had to get on the bus.”

A detainee in the Misrata detention center may also have met impersonators at disembarkation. She told Human Rights Watch that “UN police took our money” at disembarkation in Khoms in early July. “My husband had €250 and they took it,” she said.[75]

Evacuation and Repatriation

In parallel with its collective efforts to prevent boat migration from Libya, the EU is underwriting UN programs to help migrants and asylum seekers get out of arbitrary detention in Libya. While these programs have helped large numbers of people escape inhumane treatment and conditions, they have done little to address the systemic problems with immigration detention in Libya and serve as a fig leaf to cover the injustice of the EU containment policy.

With EU financial support, the UN refugee agency UNHCR began evacuating particularly vulnerable asylum seekers out of Libya to a transit center in Niamey, Niger, in December 2017. In Niamey, asylum seekers undergo full refugee status determination for the purposes of resettlement. By the end of November 2018, 2,069 had been evacuated to Niger, with an additional 312 evacuated directly to Italy and 95 to a UNHCR emergency transit center in Romania.[76] After an evacuation on October 16, UNHCR stated that their “staff endured significant security challenges and restrictions on movement to complete the evacuation as tensions amongst rival militias increase, resulting in intermittent exchanges of fire and rockets falling on Tripoli airport.”[77]

Between December 2017 and mid-November 2018, only 860 refugees were resettled out of Niger to seven EU countries (Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom), Switzerland, Canada, and the United States. In addition, 104 people were resettled directly out of Libya to Canada, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Sweden. As of mid-November 2018, nine EU countries, Norway, Switzerland, and Canada had pledged to resettle 3,886 people directly out of Libya and via Niger.[78]

The UNHCR faces severe constraints. Although Libya is a party to the 1969 Organization of the African Union Refugee Convention, it is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and has, as yet, no formal mechanism to protect individuals fleeing persecution, not to mention the practical and security obstacles to doing so in Libya at present.

Though it has operated in the country since 1991, UNHCR does not yet have a Memorandum of Understanding with the Government of National Accord that clarifies its mandate, a standard procedure in countries where UNHCR maintains an office. Negotiations on an MoU continue with little progress. Libyan authorities allow the UNHCR to register asylum seekers and refugees from only nine countries: Eritrea, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia (only members of the Oromo ethnic group), Iraq, the Syrian Arab Republic, Yemen and Palestine. Asylum seekers from these nine countries are not exempt from detention; according to UNHCR, over 3,700 nationals of these nine countries were disembarked on Libya’s western coast during the first eight months of 2018 and placed in detention.[79] This means the agency cannot register as asylum seekers persons from other countries with protection needs. As a consequence, they cannot benefit from evacuation.

UNHCR is also facilitating the return to asylum seekers currently in detention in Libya to the countries where they first registered with the agency. According to UNHCR Libya, three countries—Sudan, Ethiopia, and Chad—have agreed to receive people back in these circumstances and the agency is continuing advocacy with other countries.[80]

The EU and its member states also provide significant support to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) program for “voluntary humanitarian repatriation” from Libya to countries of origin. Since January 2017, IOM has repatriated around 30,000 people.[81] Beneficiaries receive a small amount of cash and assistance for their reintegration including counselling, support for training or schooling and, in some cases, seed money to start an income-generating activity. The range of reintegration measures varies among destination countries.[82]

The VHR program, as it is known, provides a vital service to people whose migration dream has turned into a nightmare and who want to return to their home country safely and are able to do so. Human Rights Watch spoke to numerous detainees who had experienced devastating losses and abuse along their journeys, and who wished to return home.

However, the fact that access to VHR is one of the few ways detainees can regain freedom from the abysmal conditions and treatment in detention fundamentally undermines the voluntary nature of the program.

Isaac, a 21-year-old from Nigeria detained in the Zuwara DCIM center, said:

Here, the guards told me I can’t get out unless I agree to go home. So, I’m left with no option. If I stay … it’s just a matter of time before I change my mind and go. IOM came, they told all the Nigerians to come outside. IOM said they’d give us €50.[83]

Hamza, 31, from Morocco told us violence by the guards at the Zuwara facility influenced his decision to register for repatriation with an embassy official the day before we spoke. “At the beginning, I didn’t want to return home. Now I have changed my mind. Other Moroccans want to leave too.”[84]

A humanitarian worker in Libya who wished to remain anonymous said IOM is essentially deporting people on behalf of the Libyan authorities, free of charge. These returns, and UNHCR evacuations, he said, are not real long-term solutions, and are not working to empty detention centers given the rate of interceptions followed by automatic detention. He argued that decriminalizing irregular entry and stay, and the creation of pathways to regularization of status in Libya, are key to addressing abuses against migrants in the country.[85]

Isaac began on his journey with his brother, with a plan to work in Italy to save money and then study in the United Kingdom to become a lawyer. He wished to support his widowed sick mother. Smugglers in Sebha, a southern city that serves as a major hub for migrants, held him and his brother captive where, Isaac said, they killed his brother and burned Isaac on his stomach and left arm to extort more money out of his family. “I had to call my mother to ask her for money, but she didn’t have it. She cried. That’s the last time I spoke with her. She doesn’t even know my brother is dead and I am alive.”[86]

Because Isaac did not fear for his life or his freedoms back home, he had the option to return to Nigeria as a way to escape detention, though returning would end his migration dreams. However, others risk being forced to return to places where they do face serious risks. UNHCR and IOM assert they have a mutual referral system but given the constraints on the UNHCR’s scope of action it is clear that some people in need of protection have few options.

Some detainees who might otherwise apply for asylum may opt to participate in IOM’s return program, a quicker option than registering with UNHCR and awaiting evacuation. Somalis, who are able to register with UNHCR, are reportedly signing up in large numbers for repatriation. On November 7, 2018, IOM repatriated 124 Somalis to Mogadishu, Somalia’s capital.[87] UNHCR’s special envoy for the central Mediterranean route Vincent Cochetel has commented on Twitter that IOM and UNHCR provide joint counselling to Somalis, and that many “left their country due to serious security problems…. Destitution, hunger, security concerns [in Libya] & lack of alternatives lead them to return.”[88]

IOM Libya argues its program is “absolutely voluntary in nature” and that its staff ensures that migrants “take informed decisions about their return, which includes that they have no fear of persecution upon returning.”[89]

UNHCR and IOM do not appear to have sufficient capacity to respond to the overwhelming needs of detained migrants and asylum seekers. Human Rights Watch heard repeated complaints from migrants and asylum seekers, but also from Libyan detention authorities, that IOM and UNHCR came only rarely and were not able to register enough people when they did visit. A group of 13 Ivorian women detained in the Ain Zara center told us on July 5, 2018, that they had been intercepted by the Coast Guard in mid-June. They wished to return home and were frustrated that they had not yet been registered by IOM.[90] Human Rights Watch witnessed a protest at Tajoura detention center of a group largely composed of Darfuri men asking to be registered by UNHCR.

In response to queries about their capacity, both IOM and UNHCR detailed their mandate and achievements. IOM Libya told Human Rights Watch their teams visit detention centers in Tripoli every day, and regularly arrange visits to centers located in other cities to offer “humanitarian direct assistance, health services, protection screenings (including referrals to UNHCR of the individuals who wish to seek international protection), and registration for VHR.”[91] UNHCR launched a registration campaign in October 2018, during which it registered 660 people, including Darfuris, at Tajoura center over the course of two days. The campaign has included all detention centers in Tripoli and the mountain town of Zintan and will be expanded to include centers in cities to the west of Tripoli and in and around Misrata.[92]

III. Abuses in Libyan Detention Centers

This place is like hell. They pretend to be nice people but then they flog [shock] you with electricity. Three times they beat me, when getting food. They make us sit in the sun or stand up and look straight at the sun. We protested so they hit us. They take people to the front room to beat them. They took me there, they tied my hands and then they beat me on the bottom of my feet. They hit my friend in the head.

– Elijah, 26, from Sierra Leone, detained in Misrata, July 10, 2018

In 2014, Human Rights Watch reported on migrant detention centers in Libya. At the time, in eight out of the nine centers visited, we witnessed massive overcrowding, dire sanitary conditions, and inadequate medical care. We documented torture, including beatings with all manner of implements, burning with cigarettes, electric shocks, and whippings while being hung from a tree.[93] Visits to four official detention centers in July 2018 confirmed that conditions and treatment remain nightmarish despite EU-funded efforts by international nongovernmental organizations and United Nations agencies.

Abuses

Human Rights Watch visited four DCIM centers in early July 2018. These were Tajoura and Ain Zara centers, both located on the outskirts of Tripoli, Zuwara center in the town of the same name near the border with Tunisia, and the center in the area of al-Karareem, near Misrata, a city to the east of Tripoli. We witnessed overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, inadequate health care. We heard about low quantity and poor-quality food and water in all centers.

While women are accommodated separately from men in all four centers, none of the facilities conformed with international guidelines on conditions and treatment of women in detention. All guards are male. NGOs are able to provide only limited prenatal and maternal healthcare, menstrual hygiene supplies are insufficient. Survivors of sexual violence before or during detention have extremely limited options for physical and psychological care. Accounts collected by human rights organizations and UN agencies indicate that sexual violence is a widespread phenomenon along the migration journey, in Libya, and in detention centers.[94]

In every center, staff complained of material shortages, security and health concerns for the guards, including lack of health insurance and vaccinations for staff, and disregard by international humanitarian organizations for the needs of staff. All said that the government was late in paying private contractors who provided food, water and cleaning material, which adversely affected the quantity and quality of food provided to detainees. In Misrata, the director told us that instead of spending 10 Libyan dinars per detainee (US$7) per day, catering companies were spending only 1,5 LYD (US$1).[95] As a result, none of the centers provided fresh fruit and vegetables or meat whatsoever.

No detention center has healthcare professionals on staff. Humanitarian organizations, as well as UN agencies, provide some medical attention, including maternal and post-partum care, but their access is limited.

In Misrata, Tajoura, and Zuwara we heard disturbing accounts from both adults and children of violence by guards, including beatings, whippings and use of electric shocks. Detainees in all centers said that guards treated them roughly and insulted them.

To protect migrants and asylum seekers against possible retaliation by detention center staff, Human Rights Watch decided to share deep concerns about inhumane conditions and ill-treatment with Mohamed Bishr, the head of the DCIM, at the end of the mission rather than with prison directors at the time of the visits.[96] A week later, Col. Bishr circulated a letter to all directors of DCIM facilities instructing them to respect Libyan laws and standards and international protocols in their treatment of all detainees, cooperate with civil society organizations and government institutions on human rights issues, and establish recreational activities for migrants such as beach outings and children’s activities.[97]

Col. Bishr said he suspended three DCIM staff from duty at three detention centers and referred them to the General Prosecutor for investigations after complaints of misconduct.[98] Human Rights Watch did not visit these three centers in 2018 and is not aware of any disciplinary measures taken with respect to staff at the four centers we did visit.

Col. Bishr did not respond to a November 13, 2018 letter from Human Rights Watch detailing our findings and requesting updates on implementation of guidelines and any disciplinary measures.

Misrata

Misrata is a major city 209 kilometers east of Tripoli. The migrant detention center is located in a former school in al-Karareem, just south of the city. We were allowed access to two floors of one part of the building. Men are held on the ground floor, in rooms that open onto a hallway that is accessed by a barred and locked iron door. We walked through the hallway, navigating the men standing, sitting, and lying on the floor all along the space. The bathroom at the end of the hallway has three or four stalls, with feces-encrusted holes in the floor. Upstairs we visited the women’s section, composed of two large rooms with mattresses and belongings strewn on the floor. We did not see the women’s toilets. Authorities allowed us to interview detainees individually and outside of the building. Many men and women clamored to be interviewed; we were only able to interview a few.

At the time of our visit, the center in al-Karareem held 472 detainees, according to the director: 381 men, 64 women, and 27 children up to 12 years old living with their female relatives in the women’s section. The director said there were no children between 12 and 18 years of age. He acknowledged overcrowding but implied that poor material conditions were the fault of NGOs:

There is overcrowding, people sleep in corridors. The food, living conditions and accommodation are bad, bad, bad…NGOs haven’t brought anything since the beginning of the year. We need blankets, mattresses, cleaning material. I’m supposed to burn the mattresses when people leave but we don’t have enough. In some cases, two detainees have to share one mattress. [99]

The director added that they lack baby food and sanitary pads for women, forcing staff members to buy it “from our own pockets or get it from charity.”[100]

Many interviewees complained about not being allowed outside and about poor-quality food and water. Marie-Claire, 30, from Cameroon who was among a group intercepted at sea in mid-April 2018 and who was transferred to the center in Misrata a week later, said “They [the guards] are violent. When they come, they have guns, she said. “I was never allowed to go out, I have been locked in [since I arrived]. No one goes out [to the court yard].”[101]

Oputa, a 31-year-old Nigerian woman who had been in the center for two weeks after being intercepted by the Coast Guard, said,

They beat you with a pipe if you’re not in a straight line [for food]. They never hit me, I avoid it. I often don’t go out to get food because I’m afraid of being hit. They beat the men a lot. At breakfast the men go out first. One man, they beat him so bad and they gave him electric shocks. They put him in a room near us, we could hear him screaming. Maybe it was last Thursday, a man from Sierra Leone tried to escape but they caught him. They beat him unconscious. We protested, all the women were shouting and screaming. Since then they’ve limited the beatings.[102]

She recounted that a guard had beaten a woman with a stick embedded with nails that cut her hand, the week before our visit. The same guard, Oputa said, had also hit another woman, “but in that case at least he apologized.”

Kemi, a Nigerian woman who was seven-months’ pregnant, told us a guard beat her with a hose as she was going down the stairs to get water. “He said I had to go back up, and he beat me on the arm with a hose.”[103] Hawa, 19, from Mali, was eight-and-a-half months pregnant when we spoke. She also said a guard hit her, the day before we spoke, as she was going up and down the stairs to exercise. “He hit me with his hand on my back. He said he would take me away to punish me.”[104]

Alexandra, 25, from Ghana, said,

There is ill treatment here and beatings. They [the guards] lock women inside for days. They shout at us, they beat women and flog women on the hand even if you are pregnant. One man tried to escape. They tied his neck like a dog to his legs so he cannot move his legs. They beat him seriously. He was crying like a woman. If someone tries to escape, they will beat everyone who has the same nationality as that person.[105]

Both women and men told us about a “lonely jail” on the second floor, near the women’s area, where detainees are put as punishment. Abdul, a 20-year-old from Darfur was put there after he helped three men escape:

It was one Sudanese, one Egyptian, and one from Sierra Leone. They caught the guy from Sierra Leone and beat him on the bottom of his feet and on his lower leg with a hose. They beat us in the front room, three of us. They beat me on the bottom of the feet and on my legs to get me to confess I had helped them escape. I said no, but then the other guys said it was me because they were so afraid. Then they took me to the “lonely jail,” the room in front of where the girls are. They locked us in there. The men and women shouted for us to be released. I saw the guards down below [out the window] pointing guns at the women saying they would shoot. There were nine other guys in the lonely jail, I don’t know why they were there. I spent five hours in there.[106]

A few interviewees spoke of men being subjected to electric shocks. Elijah, a 26-year-old from Sierra Leone, said there were at least four men he said were permanently affected by the application of electric shocks.

There is a man from Mali, they shocked him with electricity two months ago. He just sits on the floor. He used to speak normally, now he just stares straight ahead. They took him to the hospital but he came back in the same condition. There are three other men like that here because of electric shocks.

Human Rights Watch saw one of these men, sitting in the hallway near the toilets, sitting rigid with knees bent, hands resting on bent knees, staring straight ahead.

Ahmed, 26, from Palestine, said he left Gaza three years ago after being threatened, imprisoned and ill-treated by Hamas. He said he and others were beaten at the Misrata center. "A group from Sudan tried to escape while they were at the clinic, so the guards rounded up everyone who was at the doctor’s and beat them with plastic tubes. I was beaten a bit, but others were beaten like animals. It was collective punishment.”[107]

In a follow-up phone call after his release, Ahmed said he had been transferred to Trig el-Sikka, a detention center in Tripoli, just two days after the Human Rights Watch visit where he had been held for over two months and where he had suffered ill treatment.[108]

Two detainees said that it was possible to bribe the authorities in order to be released from al-Karareem. Naser, 48, from Syria, said “I cannot go back to Syria, I will be executed. In this place they treat you the same as a terrorist. There is no mercy or hope. But you can bribe your way out of this prison.”[109] Ahmed, the Palestinian, added, “a Sudanese and an Egyptian bribed their way out. UNHCR knows that I am in this center, so the prison authorities will not accept for me to pay my way out.”[110]

Zuwara

Zuwara is 118 kilometers to the west of Tripoli along the coast, near the Tunisian border. Until recently, it was a smuggling hub and a major departure point for boats heading towards Europe. The center, composed of connected one-story buildings, is located on a dirt road outside town. The women and young children are held in a wing with three rooms of which only two were in use, with open doors onto a hallway that ends at a barred door. The men are held in a separate wing that contains 15 cells, seven of which Human Rights Watch viewed from the iron-grated door at the entrance of the wing.

The director of the center told us there were 590 detainees at the time of our visit, including 18 women and 7 children, while the center has an official capacity of 450. He said the largest group of around 150 were from Nigeria, and there were around 111 men from Bangladesh. He said the prison management had not requested transfers to other facilities because a group of over 100 Nigerians was due to be repatriated by IOM in the following days, adding that IOM had also promised to repatriate soon 30 Bangladeshis while it remained unclear when the rest of the group would be repatriated. The director said the Bangladeshis, as well as 60 Malians, had all accepted voluntary repatriation after Skype interviews with their respective embassies. Transfers between Zuwara and Tripoli were difficult because of migrants’ attempts to flee and damage to the interior of the buses, he added.[111] Human Rights Watch found unaccompanied minors among the children held at the facility.

The director cited serious material shortages: “We need blankets, beds, hygiene kits. We don’t have a battery for the generator. I’m supposed to burn and replace beds when people leave but we don’t have enough. DCIM doesn’t give us anything.”[112]

While the 18 women and 7 children had sufficient room in their spartan rooms, the men’s section was extremely overcrowded. Human Rights Watch staff was unable to move beyond the iron-barred door and enter the hallway because men sitting or standing occupied practically every available space. All of the rooms off the hallway were filled with men who were kept indoors almost all the time despite the stifling heat. The director justified this by saying he did not have enough staff to guard such a large number of men in the facility’s courtyard. Women and children were also allowed outside only rarely. In May, the humanitarian organization MSF reported that there were over 800 people in the center at the time; it is impossible to imagine how so many more people could have fit in the spaces we saw. MSF put the center’s capacity at 200.[113]

Interviews with 29 detainees in the center confirmed that they are locked inside the wing—rooms and one hallway—virtually all day, allowed out only to wash in outdoor basins. One detainee from Ethiopia did not possess any trousers, explaining that he had lost his clothes while at sea around two weeks prior to our visit and was only wearing a shirt and a towel around his midriff. Samuel, a 29-year-old tailor from Nigeria, said, “We only come outside to wash, and not every day. They treat us like criminals. They lock us in the rooms, it’s very hot. There’s no ventilation. There is not enough space for everyone to lie down; we have to take turns.” In tentative English, Aman, a 20-year-old Eritrean, estimated there were over 40 people in his cell and said that they were “never outside, always inside.” Aman explained he left his native Eritrea because “no justice, no democracy, no peace, no education. I left because I had to be a soldier. If I go back, they’ll shoot me.”[114]

Six interviewees said guards beat detainees indiscriminately when the guards intervened in fighting in the overcrowded cells. Two others said they were threatened with beatings. Isaac, 21, from Nigeria, said, “They never let us out … it’s kind of suffocating. Some of the guards are caring, others force us inside the cells [from the hallway] when we’re making too much noise. They hit us when people fight.”[115] Idriss, another 21-year-old Nigerian, said, “The guards use sticks to beat people.”[116]

Hamza, 31, from Morocco, who was intercepted at sea in March 2018 together with a group of 120 people and again in May, said, “It’s very hot and we get little food. If there is a problem between two men, they will shut all the doors of the cells to teach us a lesson. They close us in for many hours, even during meals. They will beat us with wooden sticks or plastic tubes.”[117]

Magdi, 32, from Egypt, who had been at the center for 25 days at the time of our visit, was wearing his clothes inside out. “There are ticks and lice stuck on my clothes and I have an itch. We are allowed outside to shower every ten days or so. There is very little water,” he said. “Sometimes there are beatings. You cannot talk freely, they [the guards] are very tough and will shout ʻShut up!ʼ or ʻBe quiet!ʼ Sometimes they use wooden sticks and sometimes they use slippers to beat people.”[118]

Magdi also stated that the Zuwara police directorate stole from him. “I was held at a house in Zuwara [by smugglers] when I was arrested by the Zuwara Police Directorate. The police took my passport and money. They took all of my things and did not return anything.”[119]

Tajoura

Located to the east of Tripoli city center, the Tajoura center is located within a large compound comprising various warehouse-type buildings and another prison under the authority of the Justice Ministry known as al-Dhaman. At the time of our visit, on July 8, 2018, the director told us there were over 1,100 in total, including about 1,000 men, 100 women, and 26 children under the age of 14 detained in the center. All children over the age of 14 are counted as adults.

Detainees included Arab nationals and people from sub-Saharan Africa, including Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Niger, Nigeria, Sudan and Cameroon. According to the director, the majority of people were brought to the center after being intercepted or rescued at sea, some after multiple attempts to cross it. He mentioned the case of one Sudanese woman with two children who was “arrested” at sea on June 10, 2018, detained briefly at Tajoura, only to be brought back to the center after a second attempt to reach Europe on July 1. It was unclear how the woman left the center after her first failed attempt to reach Europe by boat.[120]

Human Rights Watch was able to enter briefly only three of the buildings, two sections where women and children were detained, and the other where men were held. The sanitary installations in the section that researchers visited were dire.

Just as we walked to towards the buildings where people are detained, a group of detainees began a protest to demand registration by the UNHCR. According to the director, 600 Sudanese nationals had gone on hunger strike the day before our visit protesting slow registration procedures. He said that all of them were asking for resettlement and despite offering to release some of them, including a pregnant woman, they all refused. A group of roughly 20 men stood in a semi-circle holding signs, one of which read: If Death is a Solution for Refugees, then Welcome to Death. The center staff prohibited us from taking photographs of the protest. Raheem, a 22-year-old from Darfur who said he had been detained in Tajoura for one year, said, “We are losing our minds just waiting. UNHCR registers Eritreans but then they wait for months. They don’t normally register us from Darfur. If this is the way it’s going to be, then don’t even save us at sea. Just let us die. That would be better than here.”[121]

A group of detainees from Darfur surreptitiously handed Human Rights Watch a note expressing deep frustration and a sense that UNHCR “doesn’t care about Darfur Refugee Issue.” According to the note, the group was arrested by the authorities in Sebratha in October 2017, when the victory of one militia over another in fighting that engulfed the city led to the discovery of roughly 14,000 people being held in smuggling warehouses.[122] They were detained in Gharyan center for four months, then transferred to Trig el-Matar center, which is on the road to the airport. They were held there for three months before being sent to Tajoura center in April 2018. None of them have been registered by UNHCR. “We spent long period we don’t know our distiny [sic] & we still waiting helps from organizations for our safety…we hope from UNHCR make care about our issue and get us out of here to safty [sic] place…(Thanks you very much) please help us.”[123]

UNHCR told Human Rights Watch it had registered 660 people at Tajoura in late October, including Darfuris.[124]