Summary

I have already lost four years of my life because I have not been able to study. It is not normal for a student to lose this much time. I want to be a doctor, but the Seleka are blocking my future.

–18-year-old student, Ngadja, January 24, 2017

The [anti-balaka] destroyed desks and chairs. We were able to get them to vacate one of the buildings so we could restart the school, but they still occupied half of the school and ruined the building... They used our school grounds as their toilet. They used the desks for firewood.

–School official, Sekia-Dalliet, January 17, 2017

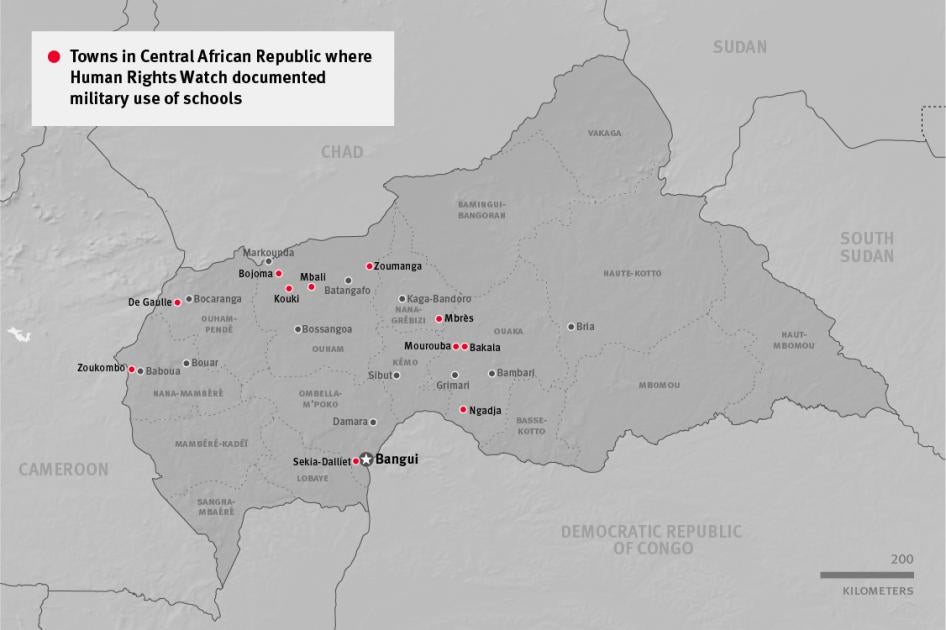

Four years after the start of the conflict in the Central African Republic—notwithstanding the return of an elected government to power—many children are still prevented from getting an education because armed groups have occupied or destroyed schools. The problem is most acute in the central and eastern provinces where fighting continues.

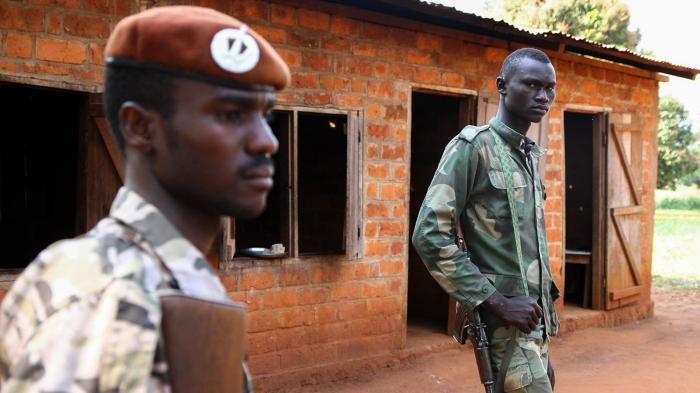

Based on interviews in November 2016 and January 2017 with over 40 people, including school-age children, parents, teachers, local officials and members of armed groups, this report documents the occupation of schools for military purposes, such as for barracks or bases. Further, the report outlines how abuses by fighters in and around schools are threatening the safety of students and teachers, as well as children’s ability to learn.

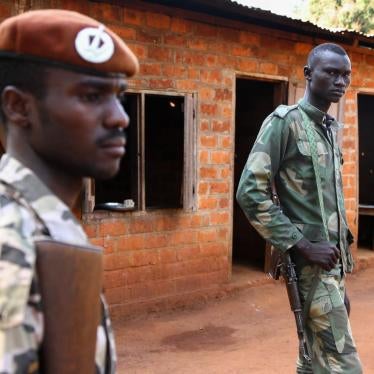

In the majority of cases documented by Human Rights Watch and other international organizations, including the United Nations, Seleka fighters were the ones who looted and occupied schools; however, anti-balaka fighters have also repeatedly committed such harmful acts. The Seleka (or “alliance” in Sango, the main national language) was a loose coalition of largely Muslim armed actors, aggrieved by years of impoverishment, insecurity and weak social services from the government of Francois Bozizé, the president from 2003 to 2013. The anti-balaka are Christian and animist militias who originally emerged to fight the Seleka, but in recent months some anti-balaka have made alliances with some Seleka splinter groups.

Fighters occupying schools expose students and teachers to risks. The military use of schools deteriorates, damages, and destroys an already insufficient and poor quality infrastructure as fighters who occupy schools often burn the desks and chairs for cooking fuel.

The use of a school by an armed group can also make the building and grounds a legitimate target for enemy attack. Even once vacated, the school may still be a dangerous environment for children if fighters leave behind unused munitions or other military equipment. In several instances documented in this report, schools that were vacated continue to be affected by the close proximity of fighters to the school grounds, restricting the ability of students to attend class.

As a country in conflict that poses serious threats to children’s health, safety and well-being, the continued military use of schools directly hampers their right to education.

During times of conflict and insecurity, maintaining access to education is of vital importance to children. If they remain safe and protective environments, schools can provide a sense of normalcy that is crucial to a child’s development and psychological well-being.

***

Violence by armed groups and attacks on civilians have risen sharply since October 2016, particularly in the central and eastern provinces of the country. Fighting between two Seleka factions in the Ouaka and Haute-Kotto provinces led to increased attacks on civilians, displacing tens of thousands of people, and shows no signs of abating. In these areas, the government of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra is struggling to maintain stability and has little presence in areas controlled by armed groups. In most parts of the country, UN peacekeepers are the only force with the capacity to protect vulnerable groups.

The gravity of the crisis in the Central African Republic has resulted in an overwhelming burden on the national government, UN agencies, and humanitarian groups. The country continues to receive inadequate funding to address multiple humanitarian emergencies, with only 4.7 percent of the $399.5 million UN appeal met.

Some children in the Central African Republic continue to suffer the negative effects of fighting and displacement, others struggle with the trauma of violence in their villages, homes, and schools. The government has the primary responsibility to ensure that communities have the resources to repair and rebuild schools that have been damaged due to fighting. This effort will require close collaboration with international partners.

In line with UN Security Council Resolution 2225 on children and armed conflict, the Central African government should take concrete measures to deter the military use of schools, including requesting assistance from the UN peacekeeping mission. In June 2015, the Central African Republic endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration, which commits governments to protect schools from attack and military use. This was an important step that spurred the UN peacekeeping mission in the country to begin clearing schools occupied by militias. Although the UN mission had a number of successes in 2016, progress was undermined by cases of peacekeeping forces themselves using school buildings as bases and barracks, in violation of UN rules.

On December 2, 2016, the Security Council Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict issued a public statement calling on all armed groups, including UN peacekeeping forces, to comply with international law and to respect the civilian character of schools.

For too many children in the Central African Republic, a safe and reliable education is not possible. In a crisis neglected on many fronts, children’s access to education should be a priority. Efforts to establish a safe environment for students are key to achieving a durable peace.

Recommendations

To the Government of the Central African Republic:

- In accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 2225, take concrete measures to deter the military use of schools, including by requesting assistance from the UN peacekeeping mission to oblige armed groups to vacate schools and school grounds;

- Ensure that students deprived of educational facilities as a result of conflict are promptly given access to alternative suitable facilities while their own schools are repaired. Request assistance from UN agencies and humanitarian actors in this regard;

- Incorporate into domestic policy, military operational frameworks or legislation, protections for schools from being used for military purposes, using as a minimum standard the Safe Schools Declaration’s “Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict”;

- Investigate attacks against students, teachers, and schools, and hold those responsible to account.

To All Armed Groups:

- Order fighters not to use school buildings or school property for camps or barracks where it would unnecessarily place civilians at risk or deprive children of their right to education;

- Order fighters currently based on or next to school property to vacate the area.

To the UN Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA):

- Fully enforce the directive issued on December 24, 2015, on the protection of schools and universities against military use;

- Remind all troops of the UN Infantry Battalion Manual, which states that UN peacekeepers shall not use schools in their operations;

- Ensure that all peacekeeping forces receive pre-deployment trainings that highlight the obligation not to use schools in their operations;

- Continue to advocate with armed groups who use schools for military purposes to vacate schools and to ensure the safe return of students.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in the Central African Republic in November 2016 and January 2017 in the Lobaye, Nana Grébizi, Nana-Mambéré, Ouaka, Ouham and Ouham-Pendé provinces. A Human Rights Watch researcher visited 12 schools and interviewed more than 40 people, including school-age children, parents, teachers, local officials and members of armed groups. Interviews were conducted in French or Sango with interpretation to French. Research on schools that had been previously occupied and vacated was conducted by field visits to each location to verify the circumstances and consequences of the occupation. Human Rights Watch spoke with relevant Seleka groups, the Central African People’s Democratic Front and MINUSCA during its research. Human Rights Watch sent written questions to Alfred Yékatom, the anti-balaka leader cited in this report; at time of writing, he had not responded.

Many of those interviewed, fearing harassment or reprisals, requested not to be named in the report. As a result, the names of witnesses and victims have been withheld. Some individuals gave consent for their photos to be used so long as their names and the photo locations were withheld. Other individuals gave permission for their photo, location and names to be published.

All of the interviewees provided their informed consent to Human Rights Watch. None of them received payment or other benefits for having given information.

I. Background

Seleka and Anti-Balaka[1]

The origins of the current conflict in the Central African Republic begin in late 2012 with the establishment of the Seleka rebel group in the northeast. The Seleka (or “alliance” in Sango, the main national language) was a loose coalition of largely Muslim armed actors, aggrieved by several years of impoverishment, insecurity and weak social services from the government of then-President Francois Bozizé.

On March 24, 2013, the Seleka seized Bangui, the capital, and ousted Bozizé and his government. The Seleka said their aim was to liberate the country and to bring security and development; however, within days, Seleka fighters unleashed waves of violence against those they perceived to have been Bozizé’s supporters, killing hundreds of civilians, possibly many more, in Bangui and across the country.[2] The Seleka rule was violent, disorganized and marked by total impunity for serious crimes.

In late 2013, Christian and animist militias known as anti-balaka began to organize counterattacks against the Seleka. (The term “anti-balaka” means “anti-balles,” or bullets, from a Kalashnikov assault rifle).[3] In response to the Seleka attacks, and with support from former government soldiers, the anti-balaka quickly grew into a loosely organized and violent militia. The group frequently targeted Muslim civilians, associating all Muslims with the Seleka.[4]

On December 5, 2013, the Security Council authorized the deployment of African Union (AU) peacekeepers and French forces already on the ground.[5] The two forces effectively pushed most Seleka fighters out of Bangui and the country’s southwest. Most Seleka fighters moved east, where the group established strongholds and split into numerous factions.

The most significant Seleka factions are the Union for Peace in the Central African Republic (l'Union pour la Paix en Centrafrique, UPC) led by Ali Darassa Mahamat in the Ouaka province; the Popular Front for the Renaissance of Central Africa (Front Populaire pour la Renaissance de la Centrafrique, FPRC), led in the Nana Grébizi province by Moussa Maloud and Lambert Lissane (but with ties to Seleka leaders Michel Djotodia and Noureddine Adam, who live outside the country); and the Central African Patriotic Movement (Mouvement Patriotique pour la Centrafrique, MPC), led in the Nana Grébizi province by Idriss Ahmned El Bachar. In late August 2016, the Seleka announced a conference to unify the branches. [6] The unification was short-lived: in November 2016, the FPRC and the UPC fought each other in the central town of Bria.[7] Conflict there spread to the Ouaka province in December 2016 as the FPRC and MPC allied with anti-balaka forces in the area.[8] Fighting between these groups remains a serious threat to the civilian population in the center of the country.

MINUSCA

In April 2014, the UN authorized a peacekeeping mission, MINUSCA, with 11,820 military personnel to take over from the AU mission. MINUSCA has a mandate to protect civilians, when necessary by force, to facilitate a political transition, and to create a secure environment for humanitarian assistance.[9] As of February 2017, 10,750 peacekeepers and 2,080 police were deployed in the country.

Attacks on Schools and Military Use of Schools by Armed Groups

The Seleka offensive adversely affected an already weak education system. Before the crisis began, the Central African Republic was ranked by one organization as one of the worst places to be a student, due to weak infrastructure, a chronic lack of teachers and disparities between the number of boys and girls. [10]

As the Seleka moved out of the northeast of the country, they looted and occupied schools. By late 2013, schools across the country had lost an average of 25 weeks of the school year.[11] Looting became so severe that in many schools there was nothing left to steal.[12] Anti-balaka groups similarly looted schools as they became more active in 2013.[13]

Attempts to quantify the effects of the use of schools by armed groups in the Central African Republic since December 2012 is complicated due to different reporting standards used by UN agencies and nongovernmental organizations, as well as limited access caused by insecurity and remoteness of locations. Further complicating matters, some schools were occupied repeatedly for short periods of time. While the absence of comprehensive data has hindered attempts to understand the full scale of the problem, some general conclusions emerge.

For example, the UN recorded 36 cases of the military use of schools, most perpetrated by Seleka groups, from late 2012 to February 2016.[14] In an April 2015 report, the education cluster – the humanitarian coordination group on education – reported that 38 percent of the 335 randomly selected schools they assessed had been attacked by armed groups. These numbers were up from two previous assessments looking at attacked schools, from August 2013 and February 2014, which had rates of 17.5 percent and 33 percent, respectfully. The April 2015 report concludes that armed groups “specifically targeted education during the September-November 2014 period, in order to impede the return to school, which is a symbol of the return to normality and stabilization.”[15]

More recently, the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated in November 2016 that 2,336 schools were operational across the country and at least 461 were not operational. It is unclear if temporary disruptions in the school calendar are reflected in this data. The key reasons for schools remaining inactive, the UN said, are insecurity, a lack of teachers, displacement, the destruction of school property or occupation of schools by armed groups.[16] Humanitarian efforts to reopen schools and to improve the education system remain seriously underfunded. In early 2016, the UN education response was only three percent funded.[17]

From 2014 to late 2016, the intensity of the violence declined but the problem of attacking or occupying schools remained. In October 2016, for example, FPRC and MPC forces attacked a school in Kaga-Bandoro, in the Nana Grébizi provinces, killing two teachers at a school where a teacher training course was being held.[18] One participant from the training course said:

A group of Seleka fighters came into the courtyard of the school. It was about 15 men… They started to shoot directly at us. One teacher, Kango, was sick and he could not keep up, he was captured and stabbed to death. I watched as they killed him. I learned later that another teacher, the director of the training center, was also killed when they found him in the neighborhood.[19]

In December, fighters from the UPC executed 25 people after calling them to a school in the town of Bakala for an alleged meeting.[20] Human Rights Watch has also received credible allegations that UPC fighters occupied a school in Liwa, 10 kilometers from Bambari, on February 21, 2017, in the days before UPC commander Ali Darassa left the town.[21]

II. Use of Schools by Armed Groups Impairs or Denies Education

The practice by armed groups, of looting schools, or using them for military purposes has been a common feature of the crisis for the past four years.[22] Members of the Seleka and anti-balaka have used schools as lodging and military positions and taken furniture for firewood.

At times, peacekeeping forces have also used schools in their operations, contrary to both local directives and international standards from the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations. The education cluster received 11 reports of schools occupied by African Union or UN peacekeepers between 2012 and January 2015.[23] The 2015 report by the UN Secretary General on Children and Armed Conflict reported that AU and French forces had used five schools in 2014.[24] The 2016 report on Children and Armed Conflict in the Central African Republic said that two contingents of the AU’s Central Africa Multinational Force[25] had occupied two schools, in Sibut and Damara, in 2013.[26]

At times, fighters converted an entire school into a barracks or military base. In other cases, they seized control of part of a school campus.

When soldiers impose themselves on schools, it puts students and teachers unnecessarily at risk and hinders students’ ability to learn. It also causes damage to school buildings, equipment, and teaching materials. Even brief military use left schools unfit for educational use without major rehabilitation.

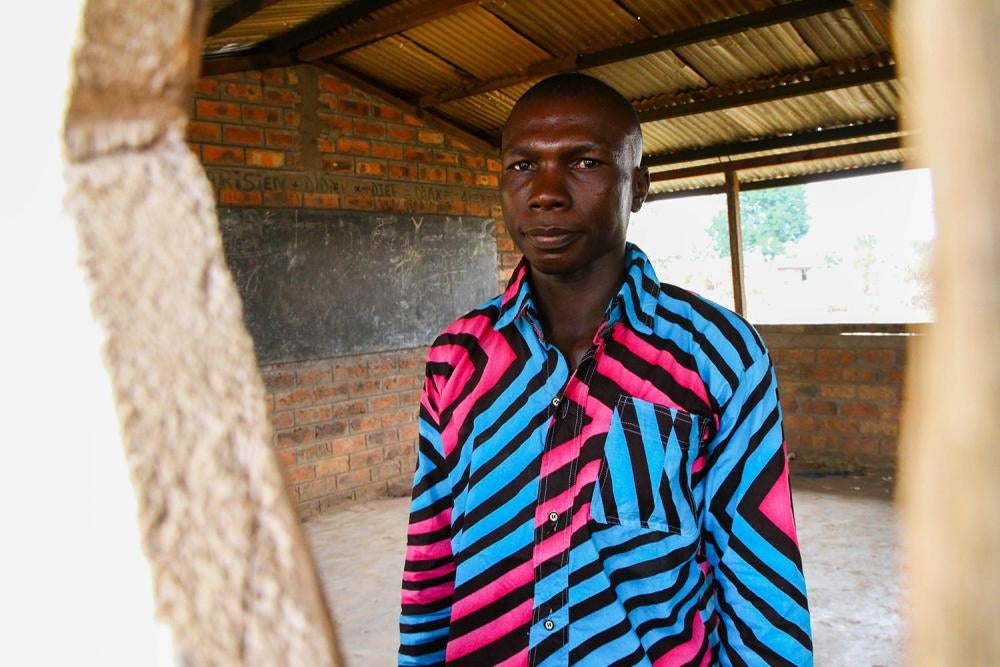

In November 2016 and January 2017, Human Rights Watch visited 12 schools that were either occupied by an armed group, had previously been occupied by an armed group or the group was in the immediate area, preventing students from attending. While some of these schools were operational, teachers and parents told Human Rights Watch of frequent closures that prevented children from attending class.

In some instances, fighters have occupied and then vacated schools, but they still operated nearby. Some of these schools were damaged during the occupation.

In one case from July 2016, in the town of Sekia-Dalliet, Lobaye province, an anti-balaka fighter beat a teacher who tried to stop him from burning a school desk. “One day an anti-balaka fighter was taking a desk to burn and I had had enough,” the teacher said, explaining that, at the time, anti-balaka fighters had been occupying the school for 22 months. “I ran up and told him to stop. I told him to put down the desk because it was for the kids. He pulled out a knife and hit me in the head. I was taken to the hospital immediately.”[27] Human Rights Watch saw scars on the teacher’s head where he said he was struck.

When Human Rights Watch visited Sekia-Dalliet in January 2017, hundreds of anti-balaka fighters were still in the town. None of them were based in the school but some were staying directly across the road. Residents of Sekia-Dalliet told Human Rights Watch that the anti-balaka there were under the command of Alfred Yékatom, alias Rombhot, currently a deputy in the National Assembly. [28]In other towns and provinces, schools were still occupied by armed groups. For example, Seleka forces from the UPC have occupied the primary school in Ngadja in the Ouaka province – which normally has 344 students –on and off since 2015, and they were still there in January 2017. They first took the school in October 2014, but left it for a few months in 2015. They re-occupied the school in December 2015 and vacated it again in 2016 for a few months, only to re-occupy it again later that year. For five months in 2015, while occupying the main school building, the Seleka used the director’s office as a prison. Teachers explained to Human Rights Watch how fighters kept prisoners in the small room for weeks and forced them to relieve themselves in the corner.

In January 2017, UPC fighters were living in the kindergarten on the school grounds and had men posted outside the main school building while children were attending school. At times they fired their guns while school was in session, teachers and students said. A student from the school explained:

The Seleka received new guns on January 13 [2017] and they were shooting them. We were in class when they started shooting behind the school. We wanted to run, but the teachers told us it was safer to stay down in the class room. I am scared to come to school. I am scared the Seleka will attack me. I often ask myself, “Should I even bother to go to school? Is it worth the risk?”[29]

Use of Schools as Places of Accommodation and Detention

Since the crisis began, multiple armed groups have used schools as temporary bases, usually when they seek shelter from rains during the rainy season, and the trend continues today. In Zoumanga, in Nana-Grébizi province, for example, Seleka fighters from the MPC occupied the only school starting in March 2014. They vacated the school building in November 2015, but set up a base on the school grounds near the road. From this road they extort money by gunpoint from passersby. In early 2016, MPC fighters re-took the school building and held it until October, when they once again moved on the school grounds near the road. A local MPC commander explained that they had no choice but to stay in the school when the rainy season started because they lacked sufficient shelter. “The school is a nice building,” he said. “And look at our tents, they are not good. So we will have to move into the school again soon once the rains come. But it is ok, the students can still come to school when we are here.”[30]

In October 2016, an armed group in the west of the country, the Central African People’s Democratic Front (Front démocratique du people centrafricain, FDPC), vacated a school in Zoukombo, in the Nana-Mambére province, at the insistence of MINUSCA, but it has threatened to reoccupy the school during the upcoming school holidays. The FDPC had occupied the school since May 20, 2016. FDPC spokesperson Gustav Guingi justified the school occupation to Human Rights Watch: “We want to be moved somewhere comfortable while we wait for DDR [Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration]. Now we are in huts and life is not good. We won’t live in the school again, but we may occupy it during the school holidays as it is not in use.”[31]

According to the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic[32], using the school as a base, the FDPC has looted goods and extorted money and valuables from villagers and travelers in the area, and negotiated payments for hostages held by the group in other areas.[33]

In June 2016, the UN Panel of Experts took photos of armed FDPC fighters stationed in front of the school.[34] On January 27, 2017, a Human Rights Watch researcher saw an FDPC fighter armed with a Kalashnikov meters away from the school perimeter as students were walking to class.

On December 11, 2016, UPC fighters attacked Bakala, a town in the Ouaka Province. After a battle with the FPRC, the UPC took control of the town. That evening they held a small group of men captive in a classroom of the École Sous-Préfectorale. The next day, they sent a message around town that there was to be a meeting at the school. When people gathered there, UPC fighters seized at least 24 men and one boy, killing 16 of them on the school grounds.[35]

MINUSCA Use of Schools

Since 2013, Human Rights Watch has documented five occasions in which armed international peacekeepers from the AU mission, MISCA, and the UN mission, MINUSCA, used schools as bases, including two cases from late 2016. In November 2016, Human Rights Watch visited a school in De Gualle in the Koui sub-prefecture in the Ouham-Pendé province and observed how MINUSCA peacekeepers from the Republic of Congo had occupied the town’s primary school and grounds. Locals said the armed peacekeepers had been there for several weeks. The commanding officer told Human Rights Watch that they were going to leave the school soon, but that it was the community’s wish for the peacekeepers to use the school.[36] The peacekeepers did leave the school in November 2016 after Human Rights Watch contacted MINUSCA staff in Bangui.

Since December 2016, Mourouba, a small town in the Ouaka province, has seen clashes between the UPC and FPRC in the area. UPC fighters took control of the town in December and killed at least three civilians, a father and his two sons, aged 1o and 16.[37] They also ransacked the school and burned documents, residents said. The town’s population fled and when they returned in January, the school was occupied by MINUSCA peacekeepers.

During a visit to the town on January 22, Human Rights Watch researchers saw MINUSCA peacekeepers from Pakistan using the school grounds as their base. Residents told Human Rights Watch that they want the peacekeepers to stay, but they also want to send their children back to school. One parent explained:

We all fled when [UPC commander] Darassa’s men arrived and when we came back the Pakistanis [MINUSCA] were in the school. They arrived sometime this month. We would like to restart the school, but now the Pakistanis are there and we would rather have MINUSCA in the town to protect us.[38]

“I hope that peace returns so the Pakistanis leave the school and we can re-open it,” a 16-year-old boy told Human Rights Watch. “I would like to be an intellectual. Without school, I will have no future, so it is important to me.”[39]

Human Rights Watch informed MINUSCA authorities of the occupied schools in De Gaulle and Mourouba and both were subsequently vacated. However, these recent occupations are troubling violations of MINUSCA’s own directive “not to use schools for any purpose” (see Section III for more details) that show how orders from Bangui are not getting implemented in the provinces. When speaking with Human Rights Watch, the MINUSCA commanding officers in De Gaulle defended their use of the school, on grounds that the local population wished them to be based there, and officers in Mourouba failed to clearly answer questions about the directive.

Dangers Keep Students from Education in Occupied Schools

In Ngadja, in the Ouaka province, the school runs despite the UPC occupation, but a school official told Human Rights Watch that hundreds of students were routinely missing class because parents were too afraid to allow them to come. One parent from Ngadja told Human Rights Watch:

I am worried that if there is a fight between the Seleka and the anti-balaka, the Seleka could seek revenge on the general population and attack our children at the school. We live far from the school, so if there is an attack or if the Seleka decide to attack our kids in revenge, I will not be able to get to our children. If I had not gone to school, I would not be able to write my name. Education gave me this ability. I hope these Seleka will leave the school so our kids can at least gain what they have lost and get a basic level of education, the same level that I got.[40]

Another parent from Ngadja made a similar point. “I am most afraid of an anti-balaka attack on the school and the kids getting caught in the crossfire,” he said. “I want the national government and MINUSCA to get this base away from the school so our kids can safely study.”[41]

In Zoumanga, Seleka fighters from the MPC are based in huts only a few meters from the school and have their meals under a tree on school property. While the Seleka fighters told Human Rights Watch they have no problem with the school and wish it to continue

running, school officials talked of a constant threat. “The Seleka sometimes shoot at pigs that walk in front of the school,” one official said. “I complained about this just a few days ago and the commander told me, ‘We are ready to close the school at any moment.’ It is very difficult to teach under these conditions and children often do not come.”[42]

School officials in Zoumanga said at least 100 students out of 392 do not come regularly to school because they fear the Seleka fighters. One parent who does not permit his children to go to the school told Human Rights Watch:

I have three kids that should be going. But the Seleka could start shooting at any moment. Sometimes they shoot their guns off and it scares the children. My kids want to go to school, but since November [2016] I have decided not to send my kids there. When peace comes back they will be able to return.[43]

Another parent from Zoumanga concurred. “The presence of the Seleka makes it too dangerous for our kids,” he said. “A gun

could go off, a child could stray too close to the Seleka and they could shoot him, or the Seleka could be attacked and shooting

could start.”[44]

Fear Keeps Students from Education in Vacated Schools

The risk to teachers and students may not end once an armed group has vacated a school. In four instances in January 2017, Human Rights Watch observed the presence of fighters in close proximity to school grounds. Several parents said they were too afraid to send their children to school because the fighters were so close.

In Bojomo, in the Ouham province, Seleka fighters vacated the local primary school in November 2016 at the behest of local authorities and MINUSCA.[45] However, one school official explained how parents are still reluctant to send children to class due to threats. “The Seleka are just down the road,” she said. “Parents are afraid to send their kids because the Seleka said they would kill people in the village. They were angry they were told to leave the school.”[46]

A parent with four school-age children said:

Since the Seleka put their base here, there has been a lot of fear on the part of the parents. Their base is still near the school. The Seleka attacked the village in 2014 and killed my husband. Seeing these Seleka here with heavy arms and us with no means to defend ourselves if they attack…it is too much. I can’t send my kids to school.[47]

In Mbrès, a town in the Nana Grébizi province, Seleka fighters allied with the FPRC and the MPC vacated two schools, a boys and girls primary school, in December 2016. The schools were meant to re-start afterwards, but they remain closed due to tensions in the town, a lack of teachers— many of whom fled during the fighting, and the close proximity of fighters to the school buildings. On January 21, Human Rights Watch researchers noted the presence of Seleka fighters just meters away from the schools.

One teacher from Mbrès told Human Rights Watch:

The schools closed in 2013. They were meant to re-open on September 21, 2016, but we decided not to because of the presence of the Seleka. At this point there was a Seleka group sleeping in each class, but that team has now moved on to Bakala. Since then they have left, but the Seleka are just next to the school and the parents are too scared to send their kids. The Seleka think it is normal to be based in schools.[48]

One student, a 15-year-old girl, told Human Rights Watch:

I am scared of the Seleka in front of my school. They look at me with red eyes when I pass. Some of them smoke drugs and it makes me scared. I have not studied since 2013. I have lost years. I want to return to school, but the presence of the Seleka means it is not possible.[49]

Another student, a 16-year-old boy, said:

When school was meant to re-start a few months ago, more Seleka came and occupied it. These Seleka have stolen my future. I am not always afraid of the Seleka. I can walk by them on the road, but sometimes the men outside the school can shoot and we don’t know where the bullet will go. I want to be a teacher because I like to read. I’d like to teach that to other kids, but now I don’t know what to do.[50]

The fears of the students are grounded in years of Seleka occupation in Mbrès. One 13-year-old girl explained:

The school closed because the Seleka came and when they first arrived they threatened to lock us into our classrooms and kill us all. That frightened me. If the school reopens and I can go, but only if other students also go… I can’t go alone. With the school closed it means I can’t be smart. My favorite subject is math and I want to be a teacher, but without the school I can’t realize my dream.[51]

Education Infrastructure Damaged and Destroyed by Military Occupation

When an armed group occupies a school, the result is frequently some amount of damage: broken or burned furniture, looted supplies. In ten of the twelve schools visited by Human

Rights Watch in November 2016 and January 2017, desks had been burned as firewood. In some instances, reading materials were deliberately destroyed.

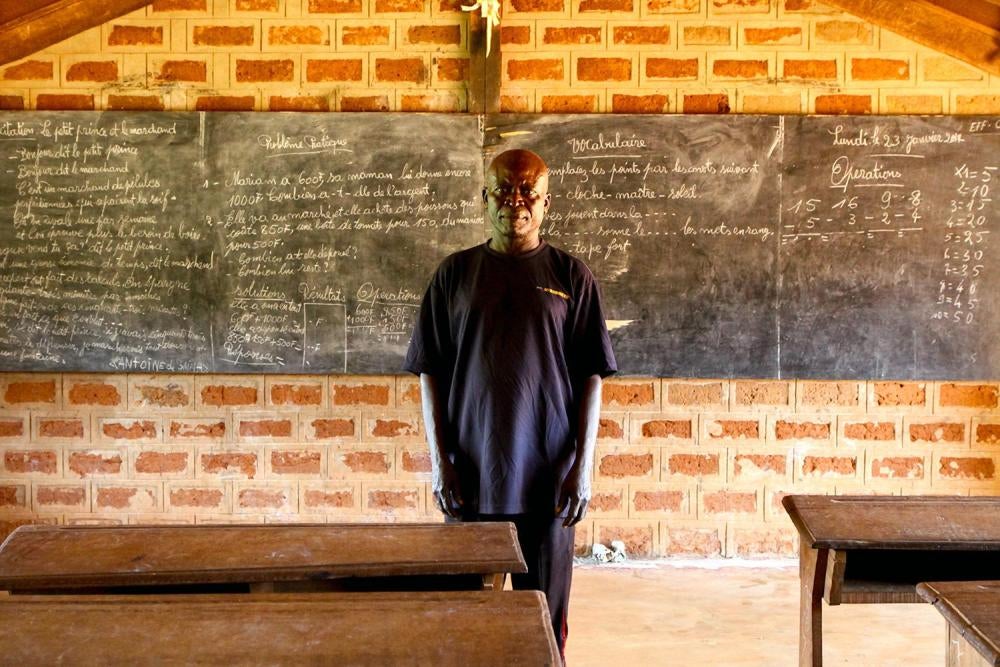

A school official from Sekia-Dalliet, where the primary school was occupied by anti-balaka fighters from late 2014 to October 2016, explained to Human Rights Watch how his school was still suffering the consequences:

They destroyed desks and chairs. We were able to get them to vacate one of the buildings so we could restart the school, but they still occupied half of the school and ruined the building. They would smoke marijuana all day and they said they were waiting for DDR [Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration]. They would go out on the main road and put up roadblocks on the street, stop vehicles and take money from them at gunpoint. They used our school grounds as their toilet. They used the desks for firewood and destroyed at least 75 of them. When the building is repaired we will use it again.[52]

The primary school in Mbali, in the Ouham province, which Seleka fighters occupied from August 2013 to July 2016, was still impacted when Human Rights Watch visited in January 2017. One teacher told Human Rights Watch:

The Seleka took the school in 2013. Some time back we asked the Seleka to leave the school, and the fact that we asked made them angry so they made a big fire and burned all the desks and the books. Now the school is functioning, but we don’t have enough books or documents with which to teach.[53]

A 16-year-old boy from the school told Human Rights Watch, “I lost three years because the Seleka took the school. Now we don’t have enough books that I need to study, so it is making restarting my life difficult. I think about it a lot.”[54]

Seleka Response

Of the 12 schools visited by Human Rights Watch in November 2016 and January 2017, eight were either occupied or continued to be affected by the occupation of Seleka fighters from the UPC, MPC, or FPRC. Commanders from the different Seleka factions did not see how the presence of their fighters at or around the schools could negatively affect children’s ability to attend school.

In Mbrès, where Seleka fighters from the MPC and FPRC occupied schools as recently as December 2016, and continue to be based meters from school grounds, the zone commander Anour Djima said:

I don’t know why parents are scared to send their kids to school. Since 2016, we have not been inside a school or taken material, so they have no reason to be afraid of us. Also, we are here for their protection. I have now said our elements can’t sleep in schools, but yes they are stationed near them for protection.[55]

None of the three schools in Mbrès have operated since 2013.

The commander of the UPC, General Ali Darassa Mahamant, told Human Rights Watch on January 23, 2017 that his men do not occupy schools but that they may be in close proximity to schools in order to protect the population.[56] Darassa’s men continue to occupy the kindergarten and are based on school grounds in Ngadja. Local UPC commanders in Ngadja told Human Rights Watch that despite their presence on the school grounds, it was their adversary, rather than the UPC, that negatively affected schools. “It is the anti-balaka who threaten the school, not the UPC,” said Raul Antoine Oubandi, the group’s local general secretary. “It is the UPC that protects the school and allows students to study.”[57]

According to local residents, hundreds of children do not attend school in Ngadja due to the UPC’s presence.

In Zoumanga, where MPC fighters occupied the primary school until late October 2016, Seleka commanders told Human Rights Watch that their roadblock, along a road on the school grounds, serves to protect the population.[58] However, several residents of Zoumanga said fighters used the roadblock to extort money and often fired their guns on school grounds.

In Bojomo, where the primary school was occupied by MPC fighters from mid-2013 to November 2016, Seleka commanders denied that they had damaged school property and told Human Rights Watch that they were near the school to protect students.[59] Some MPC fighters have killed civilians in the town, including parents of children who are too afraid to attend class.

Anti-Balaka Response

As anti-balaka fighters in Sekia-Dalliet continue to threaten residents, Human Rights Watch did not speak with fighters in town due to security concerns.

Human Rights Watch delivered a letter to Alfred Yékatom’s office at the National Assembly on March 7, 2017, outlining our research findings and asking for a response. As of March 16, he had not replied.

III. Legal Protections for Schools

Not all uses of schools for military purposes are prohibited by the laws of armed conflict. However, even military use of schools that do not violate the laws of armed conflict may nonetheless infringe on children’s right to education as guaranteed under international human rights law.

Unlawful and unnecessary misuse of schools is made more likely by a lack of clear regulations, training for soldiers on how schools should be protected from military use, and adequate logistical support.

In 2015, the Security Council, in Resolution 2225, expressed “deep concern that the military use of schools in contravention of applicable international law may render schools legitimate targets of attack, thus endangering the safety of children and in this regard encourages Member States to take concrete measures to deter such use of schools by armed forces and armed groups.”[60]

Law of Armed Conflict (International Humanitarian Law)

The law of armed conflict (also known as international humanitarian law) is the body of law that regulates conduct in armed conflicts. Under Additional Protocol II to the Geneva Conventions, applicable during non-international armed conflicts, it is a “fundamental guarantee” that children shall receive an education, in keeping with the wishes of their parents.[61]

Schools are normally civilian objects and, as such, shall not be the object of attack unless they become legitimate military objectives.[62] To intentionally direct attacks against schools when they are not legitimate military objectives constitutes a war crime. In case of doubt whether a school is being used to make an effective contribution to military action, it shall be presumed not to be so used.[63]

The law of armed conflict requires that the parties to a conflict take precautions against the effects of attack. To the extent that schools are civilian objects, parties to an armed conflict shall, to the maximum extent feasible, a) avoid locating military objectives within, or near, densely populated areas where schools are likely to be located; b) endeavor to remove the civilian population, individual civilians and civilian objects under their control from the vicinity of military objectives; and c) take the other necessary precautions to protect those schools under their control against the dangers resulting from military operations.[64]

Therefore, turning a school into a military objective (for example, by using it as a military barracks) subjects it to possible attacks from the enemy that might be lawful under the law of armed conflict. Locating military objectives (weapons, for example) in a school courtyard also increases the risk that the school will suffer incidental damage from an attack against those nearby military objectives that might be lawful under the law of armed conflict.

Account must also be taken of other relevant rules and principles of the law of armed conflict. Among these are special protections to children.[65] If education institutions are fully or partially used for military purposes, the life and physical safety of children might be at risk and access to education is restricted or even impeded, either because children may not go to school for fear of being killed or injured in an attack by the opposing forces, or because they have been deprived of their usual educational building.

International Human Rights Law

International human rights law guarantees students, teachers, academics, and all education staff the right to life,[66] personal liberty and security.[67] States shall also ensure, to the maximum extent possible, the survival and the development of children.[68]

Everyone has the right to education.[69] With a view to achieving the full realization of this right, states shall make primary education compulsory and available free to all; secondary education generally available and accessible to all; and higher education equally accessible to all on the basis of capacity.[70] The material conditions of teaching staff shall be continuously improved.[71] States shall also take measures to encourage regular attendance by children at schools and the reduction of child dropout rates.[72] With respect to children, states shall undertake such measures to the maximum extent of their available resources and, where needed, within the framework of international co-operation.

|

The Safe Schools Declaration In June 2015, the Central African Republic endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration, which is an international political commitment to strengthening the prevention of, and response to, attacks on students, teachers, and schools during armed conflict. These include collecting reliable data on attacks and military use of schools; providing assistance to victims of attacks; investigating allegations of violations of national and international law, and prosecuting perpetrators where appropriate; developing and promoting “conflict sensitive” approaches to education; and seeking to continue education during armed conflict. Countries that endorse the declaration also commit to refrain from using schools for military purposes, by using the “Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict,” which provide guidance to both armed forces and non-state armed groups on how to avoid using schools from military use, and to mitigate the negative consequences when such use occurs. In May 2016, the Peace and Security Council of the AU commended the Central African Republic for endorsing the Declaration and urged all other AU member states to do so.[73] In February 2017, the Committee on the Rights of the Child—an international body of child rights experts which oversees implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child—also welcomed the Central African Republic for its endorsement of the Safe Schools Declaration. The Committee urged the government to “take the measures necessary to deter the use of schools by parties to the conflict, including by bringing the ‘Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict’ into military policy and operational frameworks.”[74] |

Standards for Peacekeeping Forces

On December 24, 2015, the head of MINUSCA, and Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General, Parfait Onanga-Ayanga, issued a directive on the protection of schools and universities against military use. The directive states that MINUSCA forces are requested “not to use schools for any purpose” and that abandoned schools, which are occupied should be “liberated without delay in order to allow educational authorities to reopen them as soon as possible.”[75]

Moreover, according to the UN Infantry Battalion Manual, which regulates the behavior of all troop-contributors:

The military has a special role to play in promoting the protection of children in their areas of operation and in preventing violations, exploitation and abuse... Therefore, special attention must be paid to the protection needs of girls and boys who are extremely vulnerable in conflict. Important issues that require compliance by infantry battalions are … schools shall not be used by the military in their operations.[76]

Examples of Good Practice Protecting Schools from Military Use

There are precedents instituted in other countries that Central African Republic could consider as examples of good practice when developing its own protections for schools from military use through legislation, military orders or in negotiations with armed groups. Many examples of such protections come from countries that also have experience with armed conflict.

In early 2013, the then Vice Prime Minister and Minister of Defense of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Alexandre Luba Ntambo, issued a ministerial directive to the army stating:

I urge you to educate all members of the [Congolese army] that all those found guilty of one of the following shortcomings will face severe criminal and disciplinary sanctions: ... Recruitment and use of children… Attacks against schools ... requisition of schools ... for military purposes, destruction of school facilities.[77]

In the Philippines, the armed forces are required to observe this strong protection:

All [Armed Forces of the Philippines] personnel shall strictly abide and respect the following: ... Basic infrastructure such as schools, hospitals and health units shall not be utilized for military purposes such as command posts, barracks, detachments, and supply depots.[78]

The armed forces of Colombia have issued the following order:

Considering International Humanitarian Law norms, it is considered a clear violation of the Principle of Distinction and the Principle of Precaution in attacks and, therefore a serious fault, the fact that a commander occupies or allows the occupation by his troops, of ... public institutions such as education establishments.[79]

During fighting between the armed forces of Sudan and the Sudanese Peoples’ Liberation Army (SPLA), both sides agreed:

The parties specifically commit themselves to ... refrain from endangering the safety of civilians by ... using civilian facilities such as ... schools to shield otherwise lawful military targets.[80]

In Nepal, the government armed forces and Maoist fighters made the following commitment as part of their peace agreement in 2006:

Both sides agree to guarantee that the right to education shall not be violated. They agree to immediately put an end to such activities as capturing educational institutions and using them, ... and not to set up army barracks in a way that would adversely impact schools.[81]

South Sudan is currently considering a proposal to amend legislation to make military use of schools by members of the national armed forces an indictable offense, with penalties including court martial, dismissal from service, and relief from command. In September 2014, the Acting Chief of General Staff in the SPLA issued an order to all units “to reaffirm” that “all SPLA members are prohibited from…occupying or using schools in any manner.” It states any SPLA member who violates the directive is subject to the “full range of disciplinary and administrative measures available under South Sudanese and International law.”[82]

Nineteen non-state armed groups, including from Burma, India, Iran, Sudan, Syria, and Turkey, have signed deeds of commitment developed by the nongovernmental organization Geneva Call, pledging to:

... avoid using for military purposes schools or premises primarily used by children.[83]

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Lewis Mudge, researcher in the Africa Division at Human Rights Watch, and Bede Sheppard, deputy director in the Children Rights Division. Thierry Messongo, research assistant in the Africa Division, provided research and translation assistance. Fred Abrahams, associate program director, and Babatunde Olugbuji, deputy program director, edited the report. Aisling Reidy, senior legal advisor provided legal review. Savannah Tryens and Lauren Seibert, associates in the Africa division, provided additional editorial assistance. Fitzroy Hepkins and Jose Martinez provided production assistance.

Photography and video footage by Edouard Dropsy.

Human Rights Watch is deeply grateful to the Dutch Postcode Lottery for its generous support of our work to document attacks on education worldwide. Thank you for making the publication of this report possible.