Introduction

This report collects recent and historic examples of laws, court decisions, military orders, policies, and practice by governments, armed forces, non-state armed groups, and courts aimed at protecting schools and universities from use for military purposes.

The examples in this report of law, policy, and doctrine protecting schools and universities from military use should encourage more governments and non-state groups to adopt their own concrete measures to protect students, educators, and the institutions in which they study.

Since 2007, the military use of schools or universities has been documented in at least 29 countries with armed conflict or insecurity, according to the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, of which Human Rights Watch is a member. That number represents the majority of countries experiencing armed conflict during the past decade. Examples can be found in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. The military use of schools is therefore a global problem, needing international attention and response.

Schools and universities have been taken over either partially or entirely to be converted into military bases and barracks; used as detention and interrogation facilities; for training fighters; and to store or hide weapons and ammunition.

Human Rights Watch has investigated the military use of schools in Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, India, Iraq, Pakistan, Palestine, the Philippines, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Ukraine, and Yemen. Further information on our research can be found in the annex of this report.

Our research has documented how the use of schools for military purposes endangers students’ and teachers’ safety, and can interfere with students’ right to education.

***

|

Protections for education from military interference date back at least to Roman times when Emperor Constantine proclaimed that all professors of literature must be free from the obligation to accommodate or quarter soldiers in order that “they may more easily train many persons in the liberal arts.” For more on historical protections, see chapter 3. 1935: The Roerich Pact between various countries in the Americas states that educational institutions “shall be considered as neutral and as such respected and protected by belligerents.” 1948: The United Nations General Assembly adopts the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, consisting of 30 articles, including that “everyone has the right to an education.” In the following decades, various international and regional treaties and declarations repeat and elaborate on this core right. 1949: The Fourth Geneva Convention lays out protections for civilians during armed conflict, including that an occupying power—a military force controlling the territory of another country—“shall, with the cooperation of the national and local authorities, facilitate the proper working of all institutions devoted to the care and education of children.” The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which promotes respect for international humanitarian law and its implementation in national law, has elaborated that this requirement is “very general in scope,” and that occupying authorities “are bound not only to avoid interfering with [the] activities [of schools], but also to support them actively… The Occupying Power must therefore refrain from requisitioning staff, premises or equipment which are being used by such establishments.” 1977: The two Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions outline further protections for children, schools, and education, including recognizing that receiving an education is a “fundamental guarantee” for children, even in situations of non-international armed conflict. |

In 2009, the issue of the military use of schools began to garner international attention. Early that year, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child—the international body of experts that oversees implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child—recommended that parties to the treaty “fulfill their obligation therein to ensure schools as zones of peace and places where intellectual curiosity and respect for universal human rights is fostered; and to ensure that schools are protected from military attacks or seizure by militants; or used as centres for recruitment.”

Later in that year, Mexico, acting as president of the UN Security Council, noted the council “urges parties to armed conflict to refrain from actions that impede children’s access to education, in particular … the use of schools for military operations.”

Since then, both the Committee on the Rights of the Child and the Security Council, increasingly joined by other international and regional bodies, have continued to elaborate protections that should be provided to protect children’s safety and students’ right to education from the potential negative consequences of military use of schools.

In 2012, in response to this increased interest, a coalition of UN agencies and civil society organizations, including Human Rights Watch, initiated consultations with experts from the ministries of foreign affairs, education, defense, as well as the armed forces of countries from various world regions, to develop guidelines directed at both government armed forces and non-state armed groups on how to avoid using schools and mitigate the negative consequences of such use. In 2014, the government of Norway took over the global consultation on these guidelines, and in December 2014 oversaw the release of the finalized Guidelines for Protecting Schools from Military Use during Armed Conflict.

In early 2015, the governments of Norway and Argentina led a consultative process that led to the Safe Schools Declaration, a political commitment by countries to do more to protect students, teachers, schools, and universities during armed conflict, including through use of the Guidelines to refrain from using schools and universities for military purposes. As of March 14, 2017, 59 countries had endorsed the declaration.

The most recent development in the Security Council’s increased response to the problem of military use of schools came in June 2015, with the unanimously supported Resolution 2225. It expressed “deep concern that the military use of schools in contravention of applicable international law may render schools legitimate targets of attack, thus endangering the safety of children.” The Security Council encouraged all member states “to take concrete measures to deter such use of schools by armed forces and armed groups.”

See chapter 1 for more information on international law and standards protecting schools from military use.

In addition to laws and standards at the international level, many individual countries have also adopted their own laws and policies to protect schools and universities from military use. Indeed, protections for schools are likely to be most effectively guaranteed when they are explicitly enumerated domestically. Chapter 2 contains examples of legislation, military orders, jurisprudence, municipal ordinances, and other statements of doctrine and policy from around the world, including from armed non-state actors.

Most of these examples of domestic laws and policies fall within five linking themes, although some countries fall into multiple categories:

- Many countries that have experienced the military use of schools, or countries that have deployed their armed forces to conflict zones, have created new policies in response to these experiences.

- At least three countries—Burma, Nepal, and Sudan—have included commitments to refrain from all military use of schools as part of peace agreements between the government and domestic armed non-state actors.

- A number of Latin American countries have laws making university campuses immune from action by government security forces: national police and military units cannot enter the grounds without the university rector’s authorization. Such laws are related to student-led movements to reform universities in Latin America, which valued universities’ autonomy or independence from the state.

- At least six countries have laws modeled on the Manoeuvres Act enacted by the British Parliament in 1897 regulating the conducting of military manoeuvres and excluding certain areas, such as schools, from encampments or other related interferences. The UK law (and its subsequent updates) did not define what constitutes a military manoeuvre. In 1991, during the Gulf War, the then-UK minister of state for the armed forces broadly defined the term as “the strategic or tactical movement of a military force.” A fair reading of the term might also suggest that it refers to military training exercises, involving a degree of simulation, sometimes popularly referred to as “war games.” Even with this limited definition, such laws are still relevant to protecting schools from military use in light of the adage that soldiers should “fight like they train.”

- Since 2009, and hand-in-hand with increased international interest and the drafting of the Safe Schools Declaration in 2015, has been more consideration of the issue of protecting schools from military use in some domestic contexts. Further domestic examples are likely in the coming years, as demonstrated by recent policy statements from armed forces and ministries of foreign affairs.

***

Disclaimer: The inclusion of a law or policy in this collection does not reflect any assessment by Human Rights Watch as to whether the relevant country or entity has adhered to its own doctrine. Instead, the examples aim to encourage greater awareness that alternatives to military use of schools have been considered both feasible and necessary, and to ease greater monitoring for their enforcement.

Recommendations

All Countries Should:

- Endorse the Safe Schools Declaration, and thereby endorse and commit to use and bring into their domestic policy and operational frameworks the Guidelines on Protecting Schools from Military Use during Armed Conflict.

- Take concrete measures to deter the use of schools by armed forces and non-state armed groups, including through the explicit regulation of military use of schools, using the Guidelines on Protecting Schools from Military Use during Armed Conflict as a minimum standard.

I. International

African Union

African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 1981

Every individual shall have the right to education.

African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (also known as the Banjul Charter), adopted by the eighteenth Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the Organisation of African Unity, June 1981, article 17(1).

African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 1990

- 1) Every child shall have the right to an education...

- 3) States Parties to the present Charter shall take all appropriate measures with a view to achieving the full realisation of this right and shall in particular:

- a) provide free and compulsory basic education;

- b) encourage the development of secondary education in its different forms and to progressively make it free and accessible to all;

- c) make the higher education accessible to all on the basis of capacity and ability by every appropriate means;

- d) take measures to encourage regular attendance at schools and the reduction of drop-out rates;

- e) take special measures in respect of female, gifted and disadvantaged children, to ensure equal access to education for all sections of the community.

African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, adopted by the Organisation of African Unity in 1990, article 11.

Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, 2003

Article 12 - Right to Education and Training

- States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to:

- c) protect women, especially the girl-child from all forms of abuse, including sexual harassment in schools and other educational institutions and provide for sanctions against the perpetrators of such practices.

Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, 2003.

Peace and Security Council of the African Union (AU) 597th meeting, 2016

Council expressed deep concern over the continuing violations of children’s rights and violence perpetrated against children, including sexual violence, attacks against schools, as well as wanton destruction of educational infrastructure, not only during situations of armed conflicts, but also during times of peace…

Council noted with serious concern that despite African and global engagements towards the protection of children affected by armed conflict and the progress achieved to strengthen the existing legal frameworks, grave violations of children’s rights still continue in most African countries affected by conflicts. Council also noted with concern, the weak and slow implementation of existing AU and international legal instruments relating to protection of children’s rights. In this regard, Council underscored the need for all Member States to mainstream the protection of children, educational infrastructure and personnel in their public administration and management systems…

Council called on all Member States in conflict situations to comply with International Humanitarian law and to ensure that schools are not used for military purposes. In this context, Council welcomed the initiatives taken by some Member States to promote and protect the right of children to education and to facilitate the continuation of education in situations of armed conflicts. In this respect, Council commended the fifteen (15) AU Members States, namely, the Central African Republic, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Somalia, Sudan and Zambia, which have already endorsed the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use During Armed Conflicts, also popularly known as the “Safe Schools Guidelines” and urged all the other AU Member States, which have not yet done so, to also endorse these Guidelines. In the same context, Council underscored the need to further strengthen the Guidelines in order to ensure that they are applicable to all situations and circumstances…

Press Statement on the Peace and Security Council of the African Union’s 597th meeting on May 10, 2016: “Children in Armed Conflicts in Africa with particular focus on protecting schools from attacks during armed conflict.”

Peace and Security Council of the African Union 615th meeting, 2016

Council, once again, called on all Member States in conflict situations to comply with International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and to ensure that schools are not attacked and used for military purposes. In this context, Council welcomed the initiatives taken by some Member States to promote and protect the right of children to education and to facilitate the continuation of education even in situations of armed conflicts. Council further encouraged all Member States that have not yet done so, to sign the Safe Schools’ Declaration…

Press Statement on the Peace and Security Council of the African Union’s 615th meeting on August 9, 2016: “Education of Refugees and Displaced Children in Africa.”

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, 2012

Every person has the right to education.

ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, adopted November 2012, article 31(1).

Commission of Inquiry on Syria

Seventh Report, 2014

Children’s right to education has been denied by the use of schools as military bases and training camps…

The commission of inquiry recommends that all parties… Respect and protect schools and

hospitals, and maintain their civilian character.

Report of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, Human Rights Council, February 12, 2014, A/HRC/25/65, para. 78 & 157.

Fifteenth Report, 2017

Education

- 13. As defined by General Comment No. 13 of the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, “education is both a human right in itself and an indispensable means of realizing other human rights. As an empowerment right, education is the primary vehicle by which economically and socially marginalized adults and children can lift themselves out of poverty and obtain the means to participate fully in their communities.”

- 14. The legal obligations of Governments concerning the right to education consist of: (i) the duties found in article 2.1 of the ICESCR; and (ii) the more specific obligations to recognise, respect, protect and fulfil this and other rights. The obligation to fulfil incorporates both an obligation to facilitate and an obligation to provide.

- 15. Moreover, under IHL, schools may only be the object of attack by warring parties when used for military purposes, and such attacks require prior warning when the school is located in a densely populated civilian area. [Citation to International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary International Humanitarian Law, 2005, Volume I: Rules, at Rule 20.]

Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic “Special inquiry into the events in Aleppo,” A/HRC/34/64, March 1, 2017, annex I, paras. 13-15.

Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

General Comment 13: The Right to Education, 1999

There is a strong presumption of impermissibility of any retrogressive measures taken in relation to the right to education… If any deliberately retrogressive measures are taken, the State party has the burden of proving that they have been introduced after the most careful consideration of all alternatives and that they are fully justified by reference to the totality of the rights provided for in the Covenant and in the context of the full use of the State party's maximum available resources.

The right to education, like all human rights, imposes three types or levels of obligations on States parties: the obligations to respect, protect and fulfill… The obligation to respect requires States parties to avoid measures that hinder or prevent the enjoyment of the right to education. The obligation to protect requires States parties to take measures that prevent third parties from interfering with the enjoyment of the right to education. The obligation to fulfill (facilitate) requires States to take positive measures that enable and assist individuals and communities to enjoy the right to education. Finally, States parties have an obligation to fulfill (provide) the right to education…

States have obligations to respect, protect and fulfill each of the ‘essential features’ (availability, accessibility, acceptability, adaptability) of the right to education. By way of illustration, a State must respect the availability of education by not closing private schools; protect the accessibility of education by ensuring that third parties … do not stop girls from going to school; [and] fulfill (facilitate) the acceptability of education by taking positive measures to ensure that education is ... of good quality for all...

General Comment No. 13: The right to education, Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, E/C.12/1999/10, December 8, 1999, paras. 45-46, & 50.

Concluding Observations on Thailand, 2015

The Committee recommends that the State party take all necessary measures to ensure that the situation in the southern border provinces has no adverse effects on the enjoyment of the rights enshrined in the Covenant. In particular, it should ensure that schools, teachers and medical personnel are adequately protected from attacks and that everyone has access to education…

Concluding observations on the combined initial and second periodic reports of Thailand, E/C.12/THA/CO/1-2, June 19, 2015, para. 34.

Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women

Concluding Observations: India, 2014

The Committee is equally concerned that girls are subjected to sexual harassment and violence including in conflict-affected regions where the reported occupations of schools by the security forces contributes to school drop-out.

The Committee … calls upon the State party … to take measures to… Prohibit the occupation of schools by security forces in conflict-affected regions in compliance with international humanitarian and human rights law standards…

Concluding observations on the combined fourth and fifth periodic reports of India, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, CEDAW/C/IND/CO/4-5, July 18, 2014, paras. 26-27.

Committee on the Rights of the Child

Day of General Discussion on “The Right of the Child to Education in Emergency Situations”: Recommendations, 2009

With reference to the obligation under international law for States to protect civil institutions, including schools, the Committee urges States parties to fulfill their obligation therein to ensure schools as zones of peace and places where intellectual curiosity and respect for universal human rights is fostered; and to ensure that schools are protected from military attacks or seizure by militants; or use as centres for recruitment. The Committee urges States parties to criminalize attacks on schools as war crimes in accordance with article 8(2)(b) (ix) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and to prevent and combat impunity.

Day of General Discussion on “the Right of the Child to Education in Emergency Situations”: Recommendations, Committee on the Rights of the Child, 49th Session, October 3, 2008, para. 35.

OP-CAC Concluding Observations: Colombia, 2010

The Committee is … concerned over continued reports indicating the occupation of schools by the armed forces and over military operations in the vicinity of schools. The Committee recognizes the State party’s duty to guarantee the right to education throughout the territory, however underlines that military presence in the vicinity of schools significantly increases the risk of exposing school children to hostilities and retaliations by illegal armed groups.

The Committee urges the State party to immediately discontinue the occupation of schools by the armed forces and strictly ensure compliance with humanitarian law and the principle of distinction. The Committee urges the State party to conduct prompt and impartial investigations of reports indicating the occupation of schools by the armed forces and ensure that those responsible within the armed forces are duly suspended, prosecuted and sanctioned with appropriate penalties.

Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 8 of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict, Concluding observations: Colombia, U.N. Doc. CRC/C/OPAC/COL/CO/1 (2010), paras. 39-40.

OP-CAC Concluding Observations: Sri Lanka, 2010

The Committee … calls upon the State party to: (a) Immediately discontinue military occupation and use of the schools and strictly ensure compliance with humanitarian law and the principle of distinction and to cease utilizing the primary section of V/Tamil MV school and the Omanthai Central College in Vavuniya to host separatees; and (b) Ensure that school infrastructures damaged as a result of military occupation are promptly and fully restored.

Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 8 of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict, Concluding observations: Sri Lanka, CRC/C/OPAC/LKA/CO/1 (2010), para. 25.

Concluding Observations: Afghanistan, 2011

The Committee is particularly concerned that, in the prevailing conditions of conflict, schools have been used as polling stations during elections and occupied by international and national military forces.

The Committee recommends that the State party … (i) Use all means to protect schools, teachers and children from attacks, and include communities, in particular parents and children, in the development of measures to better protect schools against attacks and violence…

Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 44 of the Convention Concluding observations: Afghanistan, CRC/C/AFG/CO/1 (2011), paras. 61-62.

Concluding Observations: Syria, 2012

The Committee also expresses serious concern about consistent reports that some schools have been used by the State party’s security forces as detention centres.

The Committee strongly urges the State party … to stop using schools as detention centres, and to strictly ensure compliance with humanitarian law and the principle of distinction…

Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 44 of the Convention Concluding observations: Syria, CRC/C/SYR/CO/3-4 (2012), paras.51-52.

Concluding Observations: Thailand, 2012

[T]he Committee remains concerned that in the context of the ongoing armed violence:…

Access to education has been disrupted by the targeting of government schools and teachers by non-State armed groups and by the presence of government military and paramilitary units near the schools.

The Committee recommends that the State party:

- a) Take immediate measures to ensure that the situation in the southern border provinces has no adverse effects directly and indirectly on children…

- b) Ensure that schools are not disrupted by State military and paramilitary units and are protected from attacks by non-state armed groups…

Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 44 of the Convention Concluding observations: Thailand, CRC/C/THA/CO/3-4 (2012), paras.84-85.

Concluding Observations: Israel, 2013

The Committee urges the State party to: Cease attacks against schools and use of schools as outposts and detention centres in the OPT...

Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 44 of the Convention Concluding observations: Israel, CRC/C/ISR/CO/2-4 (2013), paras.63-64

OP-CAC Concluding Observations: Yemen, 2014

The Committee is concerned at the deliberate attacks on and occupation of schools and hospitals by all parties to the conflict and the denial of humanitarian access, all of which have a negative impact on the survival and development of children.

The Committee urges the State party to: ensure that the relevant domestic legislation explicitly prohibits the occupation and use of, and attacks on, schools and hospitals, in line with international humanitarian law; expedite the reconstruction of these facilities as appropriate; and take practical measures to ensure that cases of unlawful attacks on and/or occupation of schools and hospitals are promptly investigated and that the perpetrators are prosecuted and punished.

Concluding observations on the report submitted by Yemen under article 8, paragraph 1, of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict, CRC/C/OPAC/YEM/CO/1, February 26, 2014, paras. 29-30.

OP-CAC Concluding Observations: India, 2014

[T]he Committee is concerned at the deliberate attacks on schools by non-State armed groups, as well as the occupation of schools by State armed forces in north-eastern India and in areas where Maoist armed groups are operating.

The Committee urges the State party to take all necessary measures to prevent the occupation and use of as well as attacks on places with a significant presence of children, such as schools, in line with international humanitarian law. It also urges the State party to ensure that schools are vacated expeditiously, as appropriate, and to take concrete measures to ensure that cases of unlawful attacks on and/or occupation of schools are promptly investigated and that perpetrators are prosecuted and punished.

Concluding observations on the report submitted by India under article 8, paragraph 1, of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict, CRC/C/OPAC/IND/CO/1, July 7, 2014, paras. 28-29.

Concluding Observations: Zimbabwe, 2016

[T]he Committee remains concerned … about: … The reported use of some schools by militia groups as bases and for political purposes, as well as cases of harassment, expulsion and unlawful arrests and detention of teachers and students during and after the last parliamentary and presidential elections.... [T]he Committee urges the State party to: … Take appropriate measures to deter the military or political use of schools and establish mechanisms to monitor and investigate allegations of attacks on education facilities.

Concluding observations on the second periodic report of Zimbabwe, CRC/C/ZWE/CO/2, March 7, 2016, paras. 68-69.

Concluding Observations: Democratic Republic of Congo, 2017

The Committee notes the initiatives taken by the Government to improve access of children to schools, including … to prohibit the occupation of schools by the military back in 2013. However, it regrets that the efforts are not sufficient and a large number of school age children in the country remain out of school. In particular, the Committee expresses its serious concern that: … Armed groups continue to attack schools, student and teachers in conflict affected areas putting children at risk of abduction and recruitment and use schools for military purposes…

In the light of its general comment No. 1 (2001) on the aims of education and taking note of Goal 4 of the Sustainable Development Goals, the Committee recommends that the State party: … Implement its laws and regulations that prohibit attacks and occupation of schools by the military and take measures to bring those responsible to justice…

Concluding observations on the combined third to fifth periodic report of the Democratic Republic of Congo, CRC/C/COD/CO/3-5, February 28, 2017, paras. 39-40.

Concluding Observations: Central African Republic, 2017

While welcoming the State party’s endorsement of the Safe Schools Declaration, in June 2015, to protect education during armed conflict, the Committee is deeply concerned about attacks against students, teachers and schools as well as the military use of schools by parties to the conflict.

The Committee urges the State party to take the measures necessary to deter the use of schools by parties to the conflict, including by bringing the “Guidelines for protecting schools and universities from military use during armed conflict” into military policy and operational frameworks; and investigate and prosecute attacks against education and bring perpetrators to justice. It should further ensure that children affected by the conflict can be reintegrated into the education system, including through non-formal education programmes.

Concluding observations on the second periodic report of the Central African Republic, CRC/C/CAF/CO/2, March 8, 2017, paras. 62-63.

Convention on the Rights of the Child

Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989

- States Parties recognize the right of the child to education, and with a view to achieving this right progressively and on the basis of equal opportunity, they shall, in particular:

- a) Make primary education compulsory and available free to all;

- b) Encourage the development of different forms of secondary education, … make them available and accessible to every child…;

- c) Make higher education accessible to all on the basis of capacity by every appropriate means; …

- d) Take measures to encourage regular attendance at schools and the reduction of dropout rates.

Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of November 20, 1989, entry into force September 2, 1990, article 28.

Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, 2000

Reaffirming that the rights of children require special protection, and calling for continuous improvement of the situation of children without distinction, as well as for their development and education in conditions of peace and security,

Disturbed by the harmful and widespread impact of armed conflict on children and the long-term consequences it has for durable peace, security and development,

Condemning the targeting of children in situations of armed conflict and direct attacks on objects protected under international law, including places that generally have a significant presence of children, such as schools…

Recalling the obligation of each party to an armed conflict to abide by the provisions of international humanitarian law…

Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict, adopted by General Assembly resolution A/RES/54/263 of May 25, 2000, preamble.

Council of Europe

Protocol 1 to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, 1952

No person shall be denied the right to education.

Protocol 1 to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, 1952, article 2.

Revised European Social Charter, 1996

Part I

The Parties accept as the aim of their policy, to be pursued by all appropriate means both national and international in character, the attainment of conditions in which the following rights and principles may be effectively realised:…

- 9. Everyone has the right to appropriate facilities for vocational guidance with a view to helping him choose an occupation suited to his personal aptitude and interests.

- 10. Everyone has the right to appropriate facilities for vocational training…

Article 17 – The Right of Children and young persons to social, legal and economic protection

With a view to ensuring the effective exercise of the right of children and young persons to grow up in an environment which encourages the full development of their personality and of their physical and mental capacities, the Parties undertake, either directly or in co-operation with public and private organisations, to take all appropriate and necessary measures designed:

- (a) to ensure that children and young persons, taking account of the rights and duties of their parents, have the care, the assistance, the education and the training they need, in particular by providing for the establishment or maintenance of institutions and services sufficient and adequate for this purpose; …

- to provide to children and young persons a free primary and secondary education as well as to encourage regular attendance at schools.

Revised European Social Charter, 1996.

European Union

Charter of Fundamental Rights, 2000

Article 13 – Freedom of the arts and sciences

The arts and scientific research shall be free of constraint. Academic freedom shall be respected.

Article 14 – Right to education

- Everyone has the right to education and to have access to vocational and continuing training.

- This right includes the possibility to receive free compulsory education.

Charter of Fundamental Rights, 2000.

European Parliament recommendation to the Council of 12 March 2014 on humanitarian engagement of armed non-state actors in child protection

The European Parliament … Addresses the following recommendations to the Commissioner for Development and the Vice-President of the Commission / High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy: … call on the Member States to join international efforts to prevent attacks against and the military use of schools by armed actors through endorsing the draft Lucens Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict…

European Parliament recommendation to the Council on humanitarian engagement of armed non-state actors in child protection, 2014/2012(INI), March 12, 2014.

Geneva Conventions

Fourth Geneva Convention, 1949

Art. 50.

The Occupying Power shall, with the cooperation of the national and local authorities, facilitate the proper working of all institutions devoted to the care and education of children…

Should the local institutions be inadequate for the purpose, the Occupying Power shall make arrangements for the maintenance and education, if possible by persons of their own nationality, language and religion, of children who are orphaned or separated from their parents as a result of the war and who cannot be adequately cared for by a near relative or friend.

Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, August 12, 1949.

Protocol I Additional to the Geneva Conventions, 1977

Art 52. General protection of civilian objects

- (3) In case of doubt whether an object which is normally dedicated to civilian purposes, such as a place of worship, a house or other dwelling or a school, is being used to make an effective contribution to military action, it shall be presumed not to be so used…

Art 58. Precautions against the effects of attacks

The Parties to the conflict shall, to the maximum extent feasible:

- (a) without prejudice to Article 49 of the Fourth Convention, endeavour to remove the civilian population, individual civilians and civilian objects under their control from the vicinity of military objectives;

- (b) avoid locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas;

- (c) take the other necessary precautions to protect the civilian population, individual civilians and civilian objects under their control against the dangers resulting from military operations.

Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), June 8, 1977.

Protocol II Additional to the Geneva Conventions, 1977

Art 4.Fundamental guarantees

- 3) Children shall be provided with the care and aid they require, and in particular:

- (a) they shall receive an education, including religious and moral education, in keeping with the wishes of their parents, or in the absence of parents, of those responsible for their care…

Art 13. Protection of the civilian population

- The civilian population and individual civilians shall enjoy general protection against the dangers arising from military operations. To give effect to this protection, the following rules shall be observed in all circumstances.

Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II), June 8, 1977.

Inter-American Framework

Charter of the Organization of American States, 1967

The Member States will exert the greatest efforts, in accordance with their constitutional processes, to ensure the effective exercise of the right to education…

Charter of the Organization of American States, 1967, article 49.

Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights, 1988

Everyone has the right to education.

Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights, Protocol of San Salvador, 1988, article 13.

Inter-American Democratic Charter, 2001

Education is key to strengthening democratic institutions, promoting the development of human potential, and alleviating poverty and fostering greater understanding among our peoples. To achieve these ends, it is essential that a quality education be available to all, including girls and women, rural inhabitants, and minorities.

Inter-American Democratic Charter, 2001, article 16.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), Fourth report on human rights situation in Colombia, 2013

In addition to poverty, a number of conflict-related factors have undermined the right of children and adolescents to education: the destruction, the occupation and the forced closure of schools; the scarcity of teachers because of the threats and attacks made against them; the anti-personnel mines and unexploded ordnance in and around the schools and school sidewalks; the abusive use of school areas for military propaganda and recruitment activities; and forced displacement. Added to the aforementioned there is a high level of violence, including student harassment. The IACHR observes that Colombian boys and girls have, as well as all the boys and girls of the hemisphere, the right to access an education. The schools, within the framework of an armed conflict, are also established as instruments to prevent forced recruitment and other serious violations of children’s and adolescents’ human rights. In this regard, the Commission reiterates that schools should serve as shelter for children and provide them protection. Therefore, their use for military purposes places children in a situation of risk of attacks and impedes the exercise of their right to education.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Truth, Justice, and reparation: Fourth report on [the] human rights situation in Colombia, OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 49/13, December 31, 2013, para. 732.

International Committee of the Red Cross

Commentary on the Geneva Conventions, Volume IV, 1958

The obligation of the Occupying Power to facilitate the proper working of institutions for children is very general in scope. The provision applies to a wide variety of institutions and establishments of a social, educational or medical character, etc., which exist under a great variety of names in all modern States (e.g. child welfare centres, orphanages, children's camps, childrens’ homes and day nurseries, “medico-social” reception centres, social welfare services, reception centres, canteens, etc.). All these organizations and institutions, which play a most valuable social role even in normal times, become of increased importance in wartime when innumerable children are without their natural protectors, who have fallen on the battlefield, or have been victims of bombing, conscripted to do forced labour, interned or deported…

The Occupying Powers must, with the co-operation of the national and local authorities, facilitate the proper working of children’s institutions. That means that the occupying authorities are bound not only to avoid interfering with their activities, but also to support them actively and even encourage them if the responsible authorities of the country fail in their duty. The Occupying Power must therefore refrain from requisitioning staff, premises or equipment which are being used by such establishments and must give people who are responsible for children facilities for communicating freely with the occupation authorities; when their resources are inadequate, the Occupying Power must ensure by mutual agreement with the local authorities that the persons concerned receive food, medical supplies and anything else necessary to enable them to carry out their task. It is in that sense that the expression “the proper working” of children's institutions should be understood.

This provision assures continuity in the educational and charitable work of the establishments referred to and is of the first importance, since it takes effect at a point in children's lives when the general disorganization consequent upon war might otherwise do irreparable harm to their physical and mental development.

Commentary on the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, 1958, Volume IV, pp. 286-287.

International Covenant on Economic, Cultural and Social Rights

- The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to education …

- … [W]ith a view to achieving the full realization of this right:

- (a) Primary education shall be compulsory and available free to all;

- (b) Secondary education in its different forms, … shall be made generally available and accessible to all by every appropriate means, and in particular by the progressive introduction of free education;

- (c) Higher education shall be made equally accessible to all, …;

- (d) Fundamental education shall be encouraged or intensified as far as possible for those persons who have not received or completed the whole period of their primary education;

- (e) The development of a system of schools at all levels shall be actively pursued … and the material conditions of teaching staff shall be continuously improved.

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, adopted by General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI) of December 16, 1966, entry into force January 3, 1976, article 13.

International Red Cross and Red Crescent

Resolution 2 of 31st International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, 2011

[Annex 1]

Objective 2.1: To enhance the protection of children in armed conflict…

- (c) Protection of education in armed conflict

States take all feasible measures to prevent civilian buildings dedicated to education from being used for purposes that could cause them to lose their protection under international humanitarian law.

Resolutions of the 31st International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, Resolution 2, “4-year action plan for the implementation of international humanitarian law,” Annex 1, 2011.

League of Arab States

Arab Charter on Human Rights, 2004

- 1. The eradication of illiteracy is a binding obligation upon the State and everyone has the right to education…

- 4. The States parties shall guarantee to provide education directed to the full development of the human person and to strengthening respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.

Arab Charter on Human Rights, adopted by the Council of the League of Arab States, May 22, 2004, article 41.

Non-State Armed Groups

Deed of Commitment for the Protection of Children from the Effects of Armed Conflict, 2010

[We] solemnly commit ourselves to the following terms: …

To further endeavor to provide children in areas where we exercise authority with the aid and care they require, in cooperation with humanitarian or development organizations where appropriate. Towards these ends, and among other things, we will: … v) avoid using for military purposes schools or premises primarily used by children.

Geneva Call, Deed of Commitment under Geneva Call for the Protection of Children from the Effects of the Armed Conflict (2010), art. 7.

Safe Schools Declaration

Safe Schools Declaration, 2015

The impact of armed conflict on education presents urgent humanitarian, development and wider social challenges. Worldwide, schools and universities have been bombed, shelled and burned, and children, students, teachers and academics have been killed, maimed, abducted or arbitrarily detained. Educational facilities have been used by parties to armed conflict as, inter alia, bases, barracks or detention centres. Such actions expose students and education personnel to harm, deny large numbers of children and students their right to education and so deprive communities of the foundations on which to build their future. In many countries, armed conflict continues to destroy not just school infrastructure, but the hopes and ambitions of a whole generation of children…

Where educational facilities are used for military purposes it can increase the risk of the recruitment and use of children by armed actors or may leave children and youth vulnerable to sexual abuse or exploitation. In particular, it may increase the likelihood that education institutions are attacked…

We emphasize the importance of Security Council resolution 1998 (2011), and 2143 (2014) which, inter alia, urges all parties to armed conflict to refrain from actions that impede children’s access to education and encourages Member States to consider concrete measures to deter the use of schools by armed forces and armed non-State groups in contravention of applicable international law.

We welcome the development of the Guidelines for protecting schools and universities from military use during armed conflict. The Guidelines are non-legally binding, voluntary guidelines that do not affect existing international law. They draw on existing good practice and aim to provide guidance that will further reduce the impact of armed conflict on education. We welcome efforts to disseminate these guidelines and to promote their implementation among armed forces, armed groups and other relevant actors.

Recognizing the right to education and the role of education in promoting understanding,

tolerance and friendship among all nations; determined progressively to strengthen in practice the protection of civilians in armed conflict, and of children and youth in particular; committed to working together towards safe schools for all; we endorse the Guidelines for protecting schools and universities from military use during armed conflict, and will:

- Use the Guidelines, and bring them into domestic policy and operational frameworks as far as possible and appropriate;

- Make every effort at a national level to collect reliable relevant data on attacks on educational facilities, on the victims of attacks, and on military use of schools and universities during armed conflict, including through existing monitoring and reporting mechanisms; to facilitate such data collection; and to provide assistance to victims, in a non-discriminatory manner;…

- Meet on a regular basis, inviting relevant international organisation and civil society, so as to review the implementation of this declaration and the use of the guidelines.

Safe Schools Declaration, opened for state endorsement May 29, 2015 in Oslo, Norway. As of March 14, 2017, 59 countries had endorsed the declaration

Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict, 2014

Parties to armed conflict are urged not to use schools and universities for any purpose in support of their military effort. While it is acknowledged that certain uses would not be contrary to the law of armed conflict, all parties should endeavor to avoid impinging on students’ safety and education, using the following as a guide to responsible practice:

Guideline 1: Functioning schools and universities should not be used by the fighting forces of parties to armed conflict in any way in support of the military effort.

- (a) This principle extends to schools and universities that are temporarily closed outside normal class hours, during weekends and holidays, and during vacation periods.

- (b) Parties to armed conflict should neither use force nor offer incentives to education administrators to evacuate schools and universities in order that they can be made available for use in support of the military effort.

Guideline 2: Schools and universities that have been abandoned or evacuated because of the dangers presented by armed conflict should not be used by the fighting forces of parties to armed conflict for any purpose in support of their military effort, except in extenuating circumstances when they are presented with no viable alternative, and only for as long as no choice is possible between such use of the school or university and another feasible method for obtaining a similar military advantage. Other buildings should be regarded as better options and used in preference to school and university buildings, even if they are not so conveniently placed or configured, except when such buildings are specially protected under International Humanitarian Law (e.g. hospitals), and keeping in mind that parties to armed conflict must always take all feasible precautions to protect all civilian objects from attack.

- (a) Any such use of abandoned or evacuated schools and universities should be for the minimum time necessary.

- (b) Abandoned or evacuated schools and universities that are used by the fighting forces of parties to armed conflict in support of the military effort should remain available to allow educational authorities to re-open them as soon as practicable after fighting forces have withdrawn from them, provided this would not risk endangering the security of students and staff.

- (c) Any traces or indication of militarisation or fortification should be completely removed following the withdrawal of fighting forces, with every effort made to put right as soon as possible any damage caused to the infrastructure of the institution. In particular, all weapons, munitions and unexploded ordnance or remnants of war should be cleared from the site.

Guideline 3: Schools and universities must never be destroyed as a measure intended to deprive the opposing parties to the armed conflict of the ability to use them in the future. Schools and universities—be they in session, closed for the day or for holidays, evacuated or abandoned—are ordinarily civilian objects.

Guideline 4: While the use of a school or university by the fighting forces of parties to armed conflict in support of their military effort may, depending on the circumstances, have the effect of turning it into a military objective subject to attack, parties to armed conflict should consider all feasible alternative measures before attacking them, including, unless circumstances do not permit, warning the enemy in advance that an attack will be forthcoming unless it ceases its use.

- (a) Prior to any attack on a school that has become a military objective, the parties to armed conflict should take into consideration the fact that children are entitled to special respect and protection. An additional important consideration is the potential long-term negative effect on a community’s access to education posed by damage to or the destruction of a school.

- (b) The use of a school or university by the fighting forces of one party to a conflict in support of the military effort should not serve as justification for an opposing party that captures it to continue to use it in support of the military effort. As soon as feasible, any evidence or indication of militarisation or fortification should be removed and the facility returned to civilian authorities for the purpose of its educational function.

Guideline 5: The fighting forces of parties to armed conflict should not be employed to provide security for schools and universities, except when alternative means of providing essential security are not available. If possible, appropriately trained civilian personnel should be used to provide security for schools and universities. If necessary, consideration should also be given to evacuating children, students and staff to a safer location.

- (a) If fighting forces are engaged in security tasks related to schools and universities, their presence within the grounds or buildings should be avoided if at all possible in order to avoid compromising the establishment’s civilian status and disrupting the learning environment.

Guideline 6: All parties to armed conflict should, as far as possible and as appropriate, incorporate these Guidelines into, for example, their doctrine, military manuals, rules of engagement, operational orders, and other means of dissemination, to encourage appropriate practice throughout the chain of command. Parties to armed conflict should determine the most appropriate method of doing this.

Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict, finalized December, 2014. As of March 14, 2017, through the Safe Schools Declaration, 59 countries had endorsed the guidelines.

Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education

Report to the Commission on Human Rights, 2004

Security and the Right to Education in Emergency Situations

- 119. The Special Rapporteur also believes that security in schools forms part of the human right to education. Security means not only physical, psychological and moral safety but also a right to be educated without interruption in conditions conducive to the formation of knowledge and character development.

- 120. It is for this reason that emergencies are threats, embracing as they do a wide range of possibilities such as natural disasters, armed conflicts and situations of occupation…

The Right to Education, Report submitted by the Special Rapporteur on the right to education, Mr. Vernor Muñoz Villalobos, Economic and Social Council, Commission on Human Rights, December 17, 2004, E/CN.4/2005/50, paras. 119-120.

Communication with the government of India, 2009-2010

Communication sent

- 84. On 28 December 2009, the Special Rapporteur sent a communication regarding the conflict in India’s Bihar and Jhakhand States between the Maoist rebels (Naxalites) and government security forces.

- 85. According to information received, it was alleged that education of tens of thousands of India's most disadvantaged and marginalized children was being disrupted by the ongoing conflict between Naxalite insurgents and police and other security forces in the eastern states of Bihar and Jharkhand. Security forces are allegedly occupying government school buildings as bases for anti-Naxalite operations, sometimes only for few days but often for periods lasting years. Meanwhile, it was reported that the Naxalites are directly targeting and blowing up government schools, including those not used or occupied by security forces.

- 86. It was reported that police and paramilitary forces were occupying school buildings either temporarily or for extended periods, as part of their counter-insurgency operations. Security forces had been known to take over entire school facilities and campuses, completely shutting down the school, or occupy part of school buildings, forcing classes to continue in the reduced space and alongside the armed men. While some of these occupations had lasted only days at a time and coincide with extra protection to schools and remote locations during times such as an election, many other police occupations had been reported to last for many months and even for several years.

- 87. It was further alleged that the presence of heavily armed police and paramilitaries living and working in the same buildings where children were studying has detrimental impacts on children's studies and frequently puts the authorities in breach of their obligations to realize children's right to education.

- 88. It was reported that school principals, teachers, parents, and students have not received prior notification regarding the police occupying their schools. Concern had been expressed that this lack of notification to school authorities deprived the community of the opportunity to prepare better alternatives for continuing studies and eliminates the opportunity for local residents and their children to propose alternative locations for the police presence. Moreover, lack of notification and explanation to the students left the children confused and uncertain. Moreover, it was also reported that representatives from the Bihar and Jharkhand Departments responsible for education and schools had opposed and objected to the use of their schools by security forces, yet their objections had not been considered by the security units carrying out the school occupations.

- 89. It was further alleged that the generalized fear and disruption that results from attacks by the Naxalite rebels had lead to some students dropping out from school or experiencing interruptions to their studies. Concern had been expressed that girls especially appear likely to drop out following a partial occupation of a school. Although some students may transfer to other schools in the area if their parents can cover the related costs, many students simply drop out of education all together. The increased rate of girl students dropping out was linked to either perceived or experienced instances of harassment by the security forces of girl students. As well as leading to increased rates of students dropping out of school, long-term occupation of schools had been reported to also decrease the enrollment rate and the rate of students continuing on to higher years of study.

Communication received

- 90. On 7 April 2010, the Government responded to the communication sent by the Special Rapporteur on 28 December 2009 and informed that the Government had examined this communication and, according to the concerned State authorities, no breach of the right to education of children had been reported in Bihar. However, the concerned authorities had been sensitized to provide adequate protection in this regard, so as to enable prompt and suitable action in the event of an instance of such a breach.

Observations

- 91. The Special Rapporteur thanks the Government for its reply, but nevertheless would like to express concern regarding the conflict in India’s Bihar and Jhakhand States between the Maoist rebels (Naxalites) and government security forces and its effects in the realization of the right to education.

Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to education, Vernor Muñoz, Addendum, Communications sent to and replies received from Governments, May 17, 2010, A/HRC/14/25/Add.1, paras. 84-91.

Treaty on the Protection of Artistic and Scientific Institutions and Historic Monuments (Roerich Pact)

The historic monuments, museums, scientific, artistic, educational and cultural institutions shall be considered as neutral and as such respected and protected by belligerents …

The same respect and protection shall be accorded to the historic monuments, museums, scientific, artistic, educational and cultural institutions in time of peace as well as in war.

Treaty on the Protection of Artistic and Scientific Institutions and Historic Monuments (Roerich Pact), Apr. 15, 1935, 49 Stat. 3267, 167 L.N.T.S. 289, art. 1.

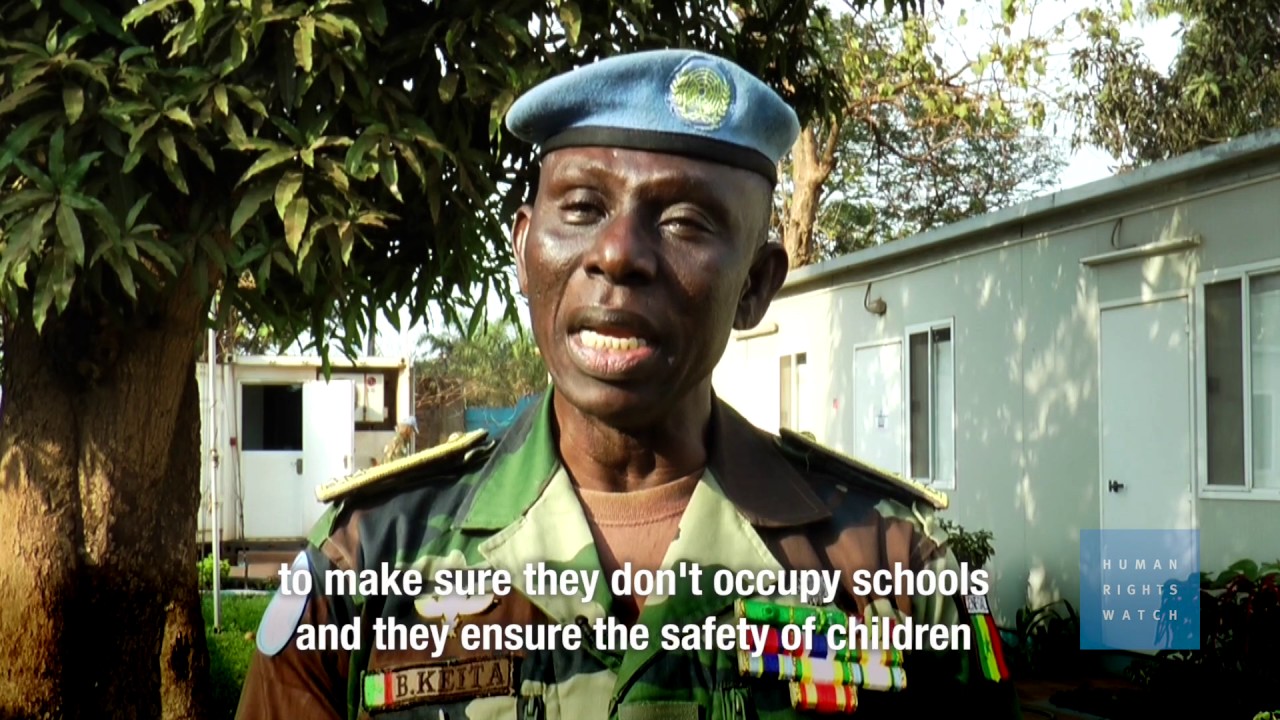

United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual, 2012

[Section] 2.13

The military has a special role to play in promoting the protection of children in their areas of operation and in preventing violations, exploitation and abuse. Relevant issues that need to be considered by unit commanders include, but are not limited to, grave violations committed against children such as recruitment and use of children by armed forces and groups, rape and grave sexual violence, killing and maiming, abductions, attacks on schools and hospitals and denial of humanitarian access as well as child sensitive Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR), and detention of children.

Therefore, special attention must be paid to the protection needs of girls and boys who are extremely vulnerable in conflict. Important issues that require compliance by infantry battalions are:

- Children should not be put in the direct line of danger…

- Schools shall not be used by the military in their operations.

Department of Peacekeeping Operations, Department of Field Support, United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual, 2012, sec. 2.13.

United Nations General Assembly

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948

- Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.

- Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

- Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UN General Assembly December 10, 1948, article 26.

The Right to Education in Emergency Situations, 2010

The General Assembly… reminding all parties to armed conflict of their obligations under international law to refrain from the use of civilian objects, including educational institutions, for military purposes and child recruitment… Urges all parties to armed conflict to fulfil their obligations under international law, in particular their applicable obligations under international humanitarian law and international human rights law, including to respect civilians, including students and educational personnel, to respect civilian objects such as educational institutions and to refrain from the recruitment of children into armed forces or groups, in accordance with their applicable obligations under international law, urges Member States to fulfil their applicable obligations under international law, including international humanitarian law, related to the protection and respect of civilians and civilian objects…

The right to education in emergency situations, A/64/L.58, June 30, 2010.

Rights of the Child Resolution, 2015

The General Assembly…

- 48. Expresses its deep concern about the growing number of attacks in contravention of international humanitarian law, as well as threats of attacks against schools, recognizes the grave impact of such attacks on children’s and teachers’ safety, as well as on the full realization of the right to education, further expresses its concern that the military use of schools in contravention of applicable international humanitarian law may also affect the safety of children and teachers and the right of the child to education, and encourages all States to strengthen efforts in order to prevent the military use of schools in contravention of applicable international humanitarian law;

- 49. Calls upon all States to give full effect to the right to education for all children and in particular:…

- (b) To take all appropriate measures to eliminate obstacles to effectively accessing and completing education, such as … armed conflicts…

- (e) To take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against girls in the field of education and to ensure equal access for all girls to all levels of education, including through … improving the safety of girls on the way to and from school, taking steps to ensure that all schools are accessible, safe, secure and free from violence …

- (m) To take necessary measures to protect schools from attacks and protected persons in relation to them in situations of armed conflict and to refrain from actions that impede children’s access to education…

Rights of the Child, A/C.3/70/L.28/Rev.1, November 18, 2015.

United Nations Security Council

Presidential Statement, April 29, 2009

The Security Council … urges parties to armed conflict to refrain from actions that impede children’s access to education, in particular … the use of schools for military operations.

Statement by the President of the Security Council, 6114th meeting of the Security Council, April 29, 2009, S/PRST/2009/9.

Resolution 1998, 2011

[The Security Council] Urges parties to armed conflict to refrain from actions that impede children’s access to education and to health services and requests the Secretary-General to continue to monitor and report, inter alia, on the military use of schools and hospitals in contravention of international humanitarian law, as well as on attacks against, and/or kidnapping of teachers and medical personnel…

Security Council Resolution 1998, July 12, 2011, S/Res/1998 (2011), para. 4.

Presidential Statement, February 12, 2013

The Security Council expresses deep concern about the severity and frequency of attacks against schools, threats and attacks against teachers and other protected persons in relation to schools, and the use of schools for military purposes, and significant implications of such attacks on the safety of students and their access to education. The Council calls upon all parties to armed conflict to put an end to such practice and to refrain from attacks against teachers and other protected persons in relation to schools, provided that they take no action adversely affecting their status of civilians.

Statement by the President of the Security Council, 6917th meeting of the Security Council, February 12, 2013, S/PRST/2013/2.

Resolution 2143, 2014

Expresses deep concern at the military use of schools in contravention of applicable international law, recognizing that such use may render schools legitimate targets of attack, thus endangering children’s and teachers’ safety as well as children’s education and in this regard:

- (a) Urges all parties to armed conflict to respect the civilian character of schools in accordance with international humanitarian law;

- (b) Encourages Member States to consider concrete measures to deter the use of schools by armed forces and armed non-State groups in contravention of applicable international law;

- (c) Urges Member States to ensure that attacks on schools in contravention of international humanitarian law are investigated and those responsible duly prosecuted;

- (d) Calls upon United Nations country-level task forces to enhance the monitoring and reporting on the military use of schools…

Security Council Resolution 2143, March 7, 2014, S/Res/2143 (2014), para. 18.

Resolution 2225, 2015

Expresses deep concern that the military use of schools in contravention of applicable international law may render schools legitimate targets of attack, thus endangering the safety of children and in this regard encourages Member States to take concrete measures to deter such use of schools by armed forces and armed groups…

Security Council Resolution 2225, June 18, 2015, S/Res/2225 (2015), para. 7.

II. Domestic

Afghanistan

Ministry of Education Memo to Ministry of Interior Affairs, 2016

[W]e are seeking the ministry’s support to follow up on the military use of schools and educational centres, and evacuation of schools and education centres of military checkpoints and military bases.

The military use of schools and educational centres, can put these premises at high risks of vulnerability. The military checkpoints/bases currently located in many schools in provinces, can convert schools into military targets of education enemies. Given the budget limitation of this ministry for reconstruction of these premises as a result of military use, please direct the concerned authorities to immediately vacate the schools from the military use in different provinces of the country.

Letter from Dr. Asadullah Hanif Balkhi, Minister of Education, to Ministry of Interior Affairs, number 311, April 2016.

Ministerial Directives, 2016

On 4 June and 4 July, the Ministry of Education sent two directives to all security-related ministries highlighting the commitment of Afghanistan to the Safe Schools Declaration and requesting security forces to stop using schools for military purposes.

Report of the Secretary-General, The situation in Afghanistan and its implications for international peace and security, S/2016/768, September 7, 2016, para. 33.

Argentina

Higher Education Act, 1995

Article 31

Public forces cannot enter the national universities without prior written order from a competent court or a request from the lawfully constituted university authority.

Ley de Educacion Superior, Ley 24,521, July 20, 1995, article 31.

Bangladesh

The Manoeuvres, Field Firing and Artillery Practice Act, 1938

Article 3

- Where a notification … has been issued, such persons as are included in the military forces engaged in the Manoeuvres may, within the specified limits and during the specified periods,-

- (a) pass over, or encamp, construct military works of a temporary character, or execute military Manoeuvres on, the area specified in the notification …

- The provisions of sub-section (1) shall not authorise entry on or interference with any … educational institution…

The Manoeuvres, Field Firing and Artillery Practice Act, Act No. 5 of 1938, March 12, 1938, art. 3.

Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Property Ordinance, 1982

When any property is required temporarily for a public purpose or in the public interest, the Deputy Commissioner may, with the prior approval of the Government, by order in writing, requisition it:

Provided that no such approval shall be necessary in the case of emergency requirement of any property:

Provided further that, save in the case of emergency requirement for the purpose of maintenance of transport or communication system, no property which is bona fide used by the owner thereof as the residence of himself or his family or which is used either for religious worship by the public or as an educational institution or orphanage or as a hospital, public library, graveyard or cremation ground shall be requisitioned.

Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Property Ordinance, April 13, 1982, art. 18(1).

Burma

Karenni National Progressive Party [KNPP] Statement on Child Soldiers, 2006

[Y]oung people were encouraged by the KNPP to go to schools run by the organization to pursue an education rather than becoming soldiers. These schools were not used for military recruitment and the students were not encouraged by the KNPP to serve in the army when they finished school.

Karenni National Progressive Party Headquarters, Statement on the Use of Child Soldiers, Statement No. 01/2006, August 31, 2006.

Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement between the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and Ethnic Armed Organizations, 2015

Chapter 3

Sec. 5: The Tatmadaw and the Ethnic Armed Organizations agree to abide by the following troop-related terms and conditions: …

- d. Avoid using any religious buildings, schools, hospitals, clinics and their premises as well as culturally important places and public spaces as military outposts or encampments…

Sec. 9: The Tatmadaw and the Ethnic Amted Organizations shall abide by the following provisions regarding the protection of civilians: …

- a. Provide necessary support in coordination with each other to improve livelihoods, health, education, and regional development for the people….

- h. Avoid restrictions on the right to education in accordance with the law; destruction of sch0ols and educational buildings, including educational tools; and the disturbance and hindrance of students and teachers….

- k. Avoid the destruction or actions that would lead to the destruction of schools, hospitals, clinics, religious buildings and their premises and the use of such places as military bases or outposts.

Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement between the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and Ethnic Armed Organizations, October 15, 2015.

Canada

Policy Statement on the Safe Schools Declaration and the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use During Armed Conflict, 2017

The world is home to more young people than at any other time in history. While great strides have been made to enhance their development and wellbeing, an estimated 250 million children live in countries and areas affected by armed conflict. Among them, girls are 2.5 times more likely to be out of school than boys. Canada shares the strong conviction to mitigate and ultimately stop the terrible effects of armed conflict on children, schools and universities. Canada strongly believes that education is a right that must be upheld, including in conflict situations. We believe that all students, girls and boys, must be able to attend school or university without fear of being targeted. Schools should be places where students come together in peace to learn about the world and their contribution to it; education can be a remedy for conflict and should never be a target of it. Protecting children and youth from all forms of violence and harmful practices is critical to upholding their rights, ensuring that they thrive, and helping them grow into engaged and productive members of society.

The Safe Schools Declaration and the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use During Armed Conflict recognize the importance of education and its role in promoting understanding, tolerance and respect for all. Canada joins other countries in endorsing the Safe Schools Declaration and, in doing so, reaffirms its commitment the protection of persons affected by armed conflict, including children.

We are concerned with the use of schools by parties to armed conflict for military purposes such as bases, barracks, weapons caches and detention centers, where such use is in contravention of international humanitarian law and we welcome efforts to address this. Eliminating all violations against children in all settings, including in situations of armed conflict, is a priority and we recognize and firmly support the need to prevent the unlawful recruitment and use of children in armed conflict, as well as for the rehabilitation and reintegration of children who have been recruited and involved in hostilities.

Compliance with international humanitarian law remains the best means to protect schools and other civilian objects from unlawful attack and we call on all parties to armed conflicts, including non-state actors, to adhere to these established international legal obligations. While not legally binding, the Declaration and associated Guidelines will inform the planning and conduct of Canadian Armed Forces operations during armed conflict, which are always carried out in full compliance with Canada’s obligations under international humanitarian law.

Canada shares the strong desire to minimize the adverse effects of armed conflict on children and we strongly agree with the importance of adhering to the protections that international humanitarian law affords to civilians and civilian objects, including schools and the students who attend them. Our endorsement of the Declaration gives us an important opportunity to reiterate our call for compliance with international humanitarian law.

Policy Statement on the Safe Schools Declaration and the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use During Armed Conflict, Global Affairs Canada, February 20, 2017.

Central African Republic