Tajikistan’s dire human rights situation worsened further in 2019. Authorities continued a crackdown on government critics, jailing opposition activists, journalists, and even social media users perceived to be disloyal for lengthy prison terms. Freedom of expression and religion are severely restricted, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are subjected to intimidation, and the internet is heavily censored. Authorities harassed relatives of peaceful dissidents abroad and used politically motivated extradition requests made via INTERPOL, the international police organization, to forcibly return political opponents from abroad.

Prison Conditions and Torture

Prison conditions are abysmal, with regular reports of torture. In November 2018 and May, two prison riots in Khujand and Vahdat, respectively, resulted in the deaths of at least 50 prisoners and five prison guards in circumstances which remain unclear. Authorities announced that it was necessary to use lethal force to put down apparently violent uprisings within the prisons. In both cases, dozens of prisoners were killed, which raised legitimate concerns about use of disproportionate or excessive force and unjustified resort to lethal force.

Another 14 prisoners died of poisoning on July 7, allegedly as the result of eating tainted bread while being transported on a truck from prisons in Khujand and Istaravshan to prisons in Dushanbe, Norak, and Yovon.

During a prison visit on March 9, imprisoned political activist and deputy head of the banned Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Mahmadali Hayit showed his wife, Savrinisso Jurabekova, injuries on his forehead and stomach that he said were caused by beatings from prison officials to punish him for refusing to record videos denouncing Tajik opposition figures abroad. Jurabekova said that her husband said he was not getting adequate medical care, and fears he may die in prison as a result of constant beatings.

Harassment of Dissidents Abroad

In December 2018, IRPT activist Naimjon Samiev was forcibly disappeared in Grozny, Chechnya, and was returned to Tajikistan, where he was sentenced to 15 years in prison on politically motivated charges.

In February 2019, Tajik and Russian officials arbitrarily detained and forcibly returned to Tajikistan Sharofiddin Gadoev, 33, a peaceful opposition activist who was visiting Moscow from his home in the Netherlands. Russian and Tajik authorities used physical force to detain him in Moscow and forced him onto a plane, beating him in Moscow and on the flight to Tajikistan. While he was held in Tajikistan, the government published choreographed videos designed to show that he “voluntarily” returned to Tajikistan. Gadoev and his relatives said the statements were made under duress. The activist was returned in March 2019 to the Netherlands following an international campaign.

In May 2019, Russian authorities arrested IRPT member Amrullo Magzumov at Vnukovo airport in Moscow at the request of the Tajik authorities. Two days later, he was forcibly returned to Tajikistan without trial.

In September 2019, Belarusian border guards detained IRPT member and independent journalist Farhod Odinaev, 42, under a Tajik extradition request after he attempted to cross the Belarus-Lithuania border on his way to attend a human rights conference in Warsaw, Poland. In November, Belarus authorities rejected Tajikistan’s request for Odinaev’s extradition.

Dissidents’ Families

Authorities regularly harass the Tajikistan-based relatives of peaceful dissidents who live abroad. Activists based in France, Germany, and Poland told Human Rights Watch that their relatives are regularly visited by security services who pressured them to denounce them and provide information on their whereabouts or activities and threatened them with imprisonment if their relatives continue their peaceful opposition work.

In June, Europe-based journalist Humayra Bakhtiyar, 33, told Human Rights Watch that authorities were harassing her family in Dushanbe in order to pressure her to return to Tajikistan. She said police had recently called her 57-year-old father, Bakhtiyar Muminov, to come for a talk on June 12, her birthday, despite her father having suffered a heart attack that required surgery in April. Police told Muminov to convince his daughter to return to Tajikistan or he would lose his job as a schoolteacher, as he had “no moral right to teach children if he was unable to raise his own daughter properly.” Police placed a call to Bakhtiyar and had her father repeat their questions into the phone. They later threated to arrest Muminov.

Freedom of Expression

Authorities regularly block access to a wide spectrum of internet news and social media sites, including YouTube, Facebook, and Radio Ozodi, the Tajik service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. They also cut access to mobile and messaging services when critical statements about the president, his family, or the government appear online. Over 25 journalists have been forced in recent years to leave the country and to live in exile.

Journalists are frequently the subject of attacks. According to the National Association of Independent Media of Tajikistan, it receives at least 10 reports each month from journalists regarding threats and restrictions on access to information while conducting their work.

Radio Ozodi came under intense pressure in October after the Tajik foreign ministry refused to extend the accreditation of 18 reporters and staff. Following a meeting in November between the president of Radio Free Europe Jamie Fly and Tajik president Emomali Rahmon, the Tajik president’s office said rumors of the closure of Radio Ozodi were “false.”

In July, Russian officials blocked the website of Asia-Plus, Tajikistan’s leading independent news agency. Later, in August, the agency’s web addresses based in Tajikistan were taken offline globally when unknown persons changed technical settings in the systems of the internet service provider. Asia-Plus, whose journalists in the past have been harassed by security services and whose website has been subjected to politically motivated blocking, moved its website to a domain hosted outside of Tajikistan. Authorities have also repeatedly denied them and other independent channels, such as the Penjiken-based Orionnur, a license to broadcast television programming.

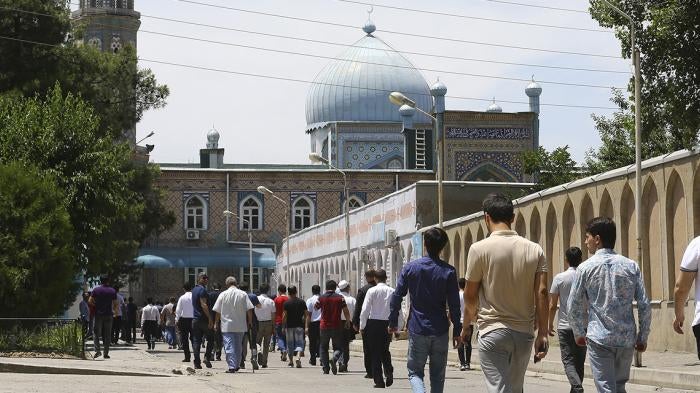

Freedom of Religion or Belief

In January, Radio Ozodi reported that officials in Dushanbe denied passports to over a dozen men unless they shaved their beards. President Rahmon has repeatedly urged Tajiks to not wear beards or hijab, and in recent years police and security services have fingerprinted and forced as many as 13,000 Tajik men to shave their beards.

In February, police arrested Shamil Khakimov, a Jehovah’s Witness based in Khujand, and seized a number of books, including copies of the Bible, which the authorities have classified as extremist literature. In August, Khakimov was placed on trial on charges of “inciting religious hatred.” Tajikistan banned Jehovah’s Witnesses in 2007.

Domestic Violence

The government has made important efforts to combat domestic violence but survivors, lawyers, and service providers reported that the 2013 domestic violence law remains largely unimplemented. Domestic violence and marital rape are not specifically criminalized. Police often refuse to register complaints of domestic violence, fail to investigate complaints, or issue and enforce protection orders. A lack of services for survivors, including immediate and longer-term shelters, leave women without clear pathways to escape abuse.

In November 2018, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) expressed concern that domestic violence is “widespread but underreported,” and that there is “systemic impunity for perpetrators … as illustrated by the low number of prosecutions and convictions” and no systematic monitoring of gender-based violence.

Key International Actors

In July, the UN Human Rights Committee (HRC) issued Concluding Observations on Tajikistan’s rights record, voicing concern over a wide spectrum of abuses, including politically-motivated imprisonment, torture, restrictions on lawyers, pressure on NGOs, domestic violence, and reports that suspected lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people were being identified and their names placed on a state registry.

In July, the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID) visited Tajikistan. The working group expressed concern that the existence of mass graves and the fate of thousands of persons unaccounted for in connection with Tajikistan’s 1992-1997 civil war remain a “virtually unaddressed issue” and that more should be done “to deal with issues related to truth, justice, reparation and memory in relation to the serious human rights violations.” The working group also pointed to a “number of recent and previous cases of Tajik individuals, reportedly political opponents who were residing abroad and were forcibly returned to Tajikistan. In some cases, these individuals have appeared in detention in Tajikistan after short periods of disappearance, while in a few instances their whereabouts are still unknown.”

In June, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention issued an opinion finding the detention of Tajik human rights lawyer, Buzurgmehr Yorov, to be a violation of international law and called for his release. The UN concluded that the charges against Yorov were baseless and that the government’s motivation was to punish him for his representation of the political opposition. Earlier rulings by the UN working group and the UN Human Rights Committee called for the release of imprisoned opposition figures Mahmadali Hayit and Zayd Saidov.

In June, Organization for Security and Co-operation Media Freedom Representative Harlem Désir called on Dushanbe to reinstate Radio Ozodi journalist Barotali Nazarov’s withdrawn press accreditation and to issue accreditation to his colleagues. He also called on authorities to investigate reports of intimidation of the family of journalist Humayra Bakhtiyar, who left Tajikistan in 2016.

In December 2018, the embassies of France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union urged the government to protect freedom of speech and media, particularly relating to the blocking of websites. At an event to mark World Press Freedom Day in May, US Ambassador John Pommersheim, former British Ambassador Hugh Philpott, and EU delegation political officer Nils Jansons renewed calls for open internet access and freedom of expression in Tajikistan.

In June, the EU and Tajikistan held the 7th Cooperation Committee meeting in Dushanbe, part of a series of meetings with high-level EU representatives. The EU emphasized freedom of expression and other fundamental freedoms, and called on the Tajik government to provide greater space for civil society.