Côte d’Ivoire’s continued political stability and strong macroeconomic growth provided a platform in 2016 for gradual improvement in the rule of law and the fulfillment of economic and social rights. A new constitution removed a divisive nationality clause—requiring a presidential candidate’s father and mother to be Ivorian—that had contributed to over a decade of political turmoil. However, little progress was made in addressing key human rights issues at the root of political violence, such as combating impunity and delivering justice for the victims of over a decade of political violence, including the 3,000 victims of the 2010-11 post-election crisis.

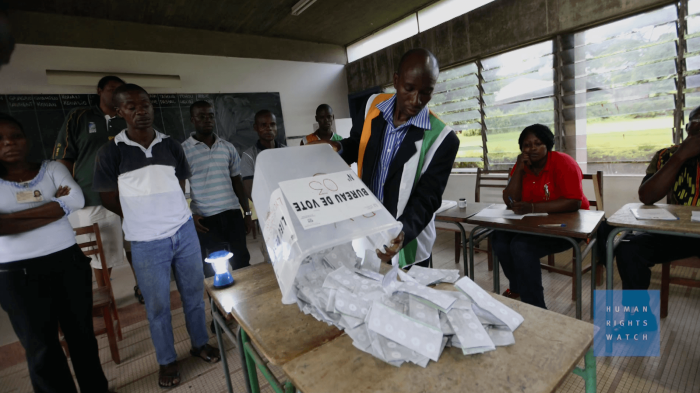

The campaign in advance of an October 30 referendum on the new constitution was characterized by some violations of the rights of freedom of assembly and expression. The new constitution contains provisions that the opposition contend significantly strengthen the power of the presidency. Côte d’Ivoire was slated to hold legislative elections on December 18.

A terrorist attack on a beach resort in Grand-Bassam on March 13 killed 22 people, including three assailants. The attack, claimed by al-Mourabitoun, an offshoot of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, underscored the risk that Côte d’Ivoire faces from regional extremist groups.

Freedom of Assembly and Expression

Ahead of the constitutional referendum, the ability of opposition parties to explain their opposition to the draft constitution was undermined by a brief seven-day campaign period, lack of access to state media, and the suspension of two opposition-leaning newspapers.

The opposition argued that the addition of a vice president and a senate, one third of which is appointed by the president, as well as a clause stating that the constitution can be amended by a two-thirds vote of the national assembly and the senate, gave undue power to the executive.

In the weeks leading up to the vote, Ivorian security forces on at least two occasions dispersed demonstrators opposed to the constitution and briefly detained several opposition leaders. Several other opposition rallies occurred without incident. Many opposition parties boycotted the vote, which was marred by modest turnout and the vandalism of dozens of polling stations in opposition strongholds.

Accountability for Past Abuses

Progress in delivering impartial justice for victims of past political violence was slow. In January 2016, the International Criminal Court (ICC) trial began of former President Laurent Gbagbo and the former youth minister and militia leader, Charles Blé Goudé, for crimes against humanity committed during the 2010-11 crisis.

An Ivorian court tried former First Lady Simone Gbagbo for crimes against humanity and war crimes during the crisis. The ICC and national judges are investigating high-level perpetrators from pro-Ouattara forces but had yet to bring them to trial at time of writing.

The Special Investigative and Examination Cell, established in 2011, continued its investigations into human rights crimes committed during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis. The cell has charged high-level perpetrators from both sides, including several pro-Ouattara commanders now in senior positions in the Ivorian army.

The only national civilian trial for human rights crimes so far, however, is that of Simone Gbagbo, whose trial in Côte d’Ivoire’s highest criminal court (cour d’assises) for crimes against humanity and war crimes began on May 31, 2016. Human rights groups acting on behalf of victims decided not to participate in the trial, citing violations of victims’ due process rights. In May, the Ivorian Supreme Court denied Simone Gbagbo’s appeal of her March 2015 conviction and 20-year sentence for offenses against the state during the post-election crisis.

The ICC has also indicted Simone Gbagbo, but the Ivorian government has refused to transfer her to The Hague. The ICC’s long-delayed investigations into crimes committed by pro-Ouattara forces continued during 2016, although President Ouattara has said that all further cases related to the post-election crisis will be tried in national courts.

A military court on February 18 convicted 13 military personnel, including Gen. Dogbo Blé, the former leader of Gbagbo’s Republican Guard, and Commander Anselme Séka Yapo, former head of protection detail of Simone Gbagbo, for the 2002 assassination of former coup leader and Ivorian president, Gen. Robert Gueï and his family. Neither the special cell nor the ICC are investigating crimes committed during election-related violence in 2000 or the 2002-2003 armed conflict.

Côte d’Ivoire’s reparations body had, when it submitted its report in April 2016, compiled a list of more than 316,000 victims potentially eligible for reparations, although the vast majority of victims have yet to receive assistance. The government on October 25 published the report of the Dialogue, Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which completed its work December 2014, although the report does little to identify those responsible for crimes committed during the 2002-2003 conflict or 2010-11 crisis.

Judicial System

Sessions of the cour d’assises were held in Abidjan and several regional courts, an essential step to clear the backlog of serious criminal cases. However, approximately 40 percent of the prison population remains in pretrial detention, often for several years. Despite the conditional release since December 2015 of some 100 pro-Gbagbo defendants arrested for their alleged role in the post-election crisis or subsequent attacks against the state, more than 200 remained in extended pretrial detention.

Most prisons are overcrowded and detainees lack adequate nutrition, sanitation, and medical care. On February 20, 2016, an uprising in Abidjan’s central prison (Maison d’Arrêt et de Correction), led to the death of a prison guard and 10 inmates, including a gang leader responsible for systematic racketeering inside the facility.

Fear of violent crime committed by street gangs, including by children, fueled several public lynchings of suspected criminals. Although the government has taken steps to eliminate its use of the word “germ” (“microbe”) to describe children in criminal gangs, it has yet to develop a comprehensive strategy to address the social, psychological, and economic drivers of violent crime by children.

Conduct of Security Forces

The prevalence of arbitrary arrests, mistreatment of detainees, and unlawful killings by the security forces lessened in 2016. Investigations and prosecutions of those who do commit abuses increased slightly, but were still rare. The military justice system remains severely under-resourced, and needs reform to strengthen its independence from the executive.

The security forces continued to engage in extortion, parallel tax systems and other criminal conduct to obtain revenue from the illicit exploitation of cocoa, diamonds, and other natural resources. Commanders allegedly responsible for severe human rights violations remain in positions of authority within the armed forces and several have allegedly illicitly accumulated private wealth and personal armories.

Extortion by security forces at illegal checkpoints remains an acute problem on secondary roads in rural areas. The United Nations reported that in March, in Assuéfry northeastern Côte d’Ivoire, the Ivorian army fired on protesters angry at soldiers’ continued extortion, resulting in the death of three persons.

Communal Violence and Land Rights

In March, violent intercommunal clashes between pastoralists and farmers in Bouna, in the northeast, left at least 27 people dead and thousands more displaced. Armed traditional hunters, known as Dozo, intervened in the conflict and were responsible for at least 15 of the killings. The government subsequently charged the Dozo chief from Bouna with murder, and some 70 Dozos were among more than 115 people arrested for their role in the violence. More than 75 people at time of writing remained in detention awaiting trial.

Land conflicts between migrant and indigenous communities underscored episodic violence in southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, including a December 2, 2015 attack by Ivorian and Liberian militiamen in Olodio that killed seven Ivorian soldiers. The December 2015 resumption of the repatriation of refugees from Liberia, on hold during the Ebola crisis, increased competition for land in western Côte d’Ivoire.

In an effort to restore Côte d’Ivoire’s dwindling forests, the government in July evicted more than 15,000 cocoa farmers from Mont Péko National Park, leaving many families without access to sufficient food, shelter, or sanitation. Smaller-scale evictions from protected forests were frequently conducted without adequate notice, and farmers were beaten and extorted during eviction operations.

Violence against Women and Girls

Gender-based violence remains widespread, particularly against girls. A July UN report found that of 1,129 rapes reported between 2012 and 2015, more than two-thirds of victims were children. Because the cour d’assises mandated to try rape cases rarely functions, Ivorian judges frequently reclassify rape cases to lesser offenses, although cour d’assises did hear at least 15 rape cases in 2016, resulting in more than a dozen convictions.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

No law prohibits discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, gender identity, or intersex status. Côte d’Ivoire does not criminalize same-sex conduct, but the criminal code establishes higher penalties for same-sex couples convicted of public acts of indecency. Two men were in November convicted of public indecency and sentenced to three-month prison terms after being accused of same-sex sexual acts. Two gay men were assaulted in June after a photo was published of them signing a book of condolences to the victims of a shooting at a gay nightclub in Florida, US.

Human Rights Defenders

Although in June 2014 the government passed a law that strengthened protections for human rights defenders, it has so far failed to adopt a decree to facilitate the law’s implementation. International and national human rights groups generally operate without government restrictions.

Key International Actors

On April 28, 2016, the UN Security Council extended the mandate of the UN peacekeeping mission, the UN Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI), for a final time, to June 30, 2017. The UN Security Council also terminated the arms embargo and individual sanctions first imposed in 2004. UNOCI progressively reduced its military and civilian components throughout 2016, leaving France, the European Union, and the United States as the government’s principal partners on justice and security sector reform.