Corruption, poverty, and repression continue to plague Equatorial Guinea under President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who has been in power since 1979. Vast oil revenues fund lavish lifestyles for the small elite surrounding the president, while a large proportion of the population continues to live in poverty. Mismanagement of public funds and credible allegations of high-level corruption persist, as do other serious abuses, including torture, arbitrary detention, secret detention, and unfair trials.

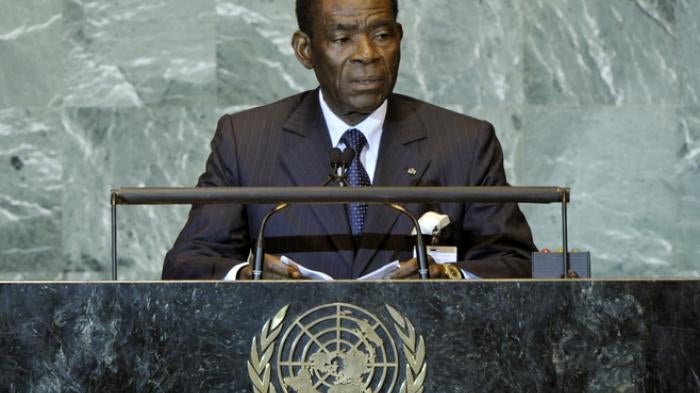

Throughout the year, President Obiang made sizable donations to international organizations, hired public relations firms, traveled widely to visit leaders in other countries, and hosted international events in order to improve his image. His efforts bore some results: the United Nations secretary-general and other dignitaries made official visits during the African Union Summit held in June, and an association of Portuguese-speaking countries in July accepted Equatorial Guinea’s bid for membership, which the country had pursued for a decade.

Obiang’s eldest son and possible successor, Teodorin, was indicted in France in March on money-laundering charges stemming from a long-running investigation, while the United States agreed to settle its forfeiture claim against Teodorin in October in a separate case that produced thousands of pages of evidence of alleged corruption, extortion, and money laundering. To pay the US$30 million settlement, Teodorin had to sell his Malibu mansion and other US holdings. The US Justice Department said the seized assets would be used to benefit Equatorial Guinea’s people.

Economic and Social Rights

Equatorial Guinea is among the top five oil producers in sub-Saharan Africa and has a population of approximately 700,000 people. It is classified as a high-income country by the World Bank. According to the UN 2014 Human Development Report, the country has a per capita gross domestic product of $37,478.85, which is the highest wealth ranking of any African country and one of the highest in the world, yet it ranks 144 out of 187 countries in the Human Development Index that measures social and economic development. As a result, Equatorial Guinea has by far the world’s largest gap of all countries between its per capita wealth and its human development score.

Despite the country’s abundant natural resource wealth and government’s obligations to advance the economic and social rights of its citizens, it has directed little of this wealth to meet their needs. About half of the population lacks access to clean water and basic sanitation facilities, according to official 2012 statistics. Childhood malnutrition, as seen in the percentage of children whose growth is stunted, stands at 35 percent, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF. A large portion of the population also lacks access to quality healthcare, decent schools, or reliable electricity. Net enrollment in primary education was only 61 percent in 2012. Despite tremendous resources, Equatorial Guinea has very low vaccination rates, including the worst polio vaccination rate in the world, 39 percent, according to the World Health Organization. As of mid-2014, five cases of polio were confirmed there, prompting a belated vaccination campaign.

The government’s statistics are unreliable and it makes few efforts to reliably track basic indicators. International organizations frequently have to make their estimates based on computer models because they only have limited information. According to such models, Equatorial Guinea has reduced maternal mortality rates by 81 percent since 1990 and has met a Millenium Development Goal target ahead of schedule.

The government does not publish basic information on budgets and spending, and citizens and journalists are unable to effectively monitor the use of the country’s natural resource wealth. In August, the government confirmed that it would seek to reapply to an international transparency initiative on oil, gas, and mining payments from which it was expelled in 2010. A key requirement of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is that governments openly engage with activists about the management of the country’s natural resources, without intimidation or reprisal, and guarantee an “enabling environment” for their full participation.

Freedom of Expression and Association

Equatorial Guinea has long had a poor record on press freedom. In January, security officials detained two Financial Times journalists for several hours and confiscated their computers, notebooks, and recording equipment, which were not returned. The journalists were able to recover their passports and mobile phones, then left the country earlier than planned.

Local journalists are unable to criticize the government or address issues the authorities disapprove of without risk of censorship or reprisal. Only a few private media outlets exist in the country, and they are generally owned by persons close to President Obiang; self-censorship is common. Foreign news is available to the small minority with access to satellite broadcasts and the Internet; others have access only to limited foreign radio programming.

Freedom of association and assembly are severely curtailed in Equatorial Guinea, greatly limiting space for independent groups. The government imposes restrictive conditions on the registration and operation of nongovernmental groups. The country has no legally registered independent human rights groups. The few local activists who seek to address human rights-related issues face intimidation, harassment, and reprisals.

Political Parties and Opposition

The ruling Democratic Party (PDGE) maintains a monopoly over political life. All but two officially recognized political parties are aligned with the ruling party. Equatorial Guinea’s two-chamber parliament with a total of 175 seats has only one opposition representative in each chamber. President Obiang appointed 20 senators, five more than allowed under the 2011 constitution.

Members of the political opposition face arbitrary arrest, intimidation, and harassment. In July, Santiago Martín Engono Esono, the leader of the youth wing of the Convergence for Social Democracy (CPDS), was arbitrarily arrested and jailed for five days in Bata, the country’s second largest city.

In August, President Obiang announced that a national political dialogue scheduled for November would for the first time include opposition leaders in exile. In preparation for this dialogue, President Obiang declared general political amnesty for exiled opposition figures in October but did not extend it to jailed political prisoners convicted for alleged security offenses. In part for this reason, three political parties, including the only opposition party with representation in parliament, withdrew from the dialogue and declared it a failure.

Presidential elections are scheduled for 2016 but there is speculation they may be brought forward in 2015. National legislative elections in 2013 were marred by serious human rights violations and a denial of fundamental freedoms, including arbitrary arrests and restrictions on freedom of assembly.

Torture, Arbitrary Detention, and Unfair Trials

Due process rights are routinely flouted in Equatorial Guinea and prisoner mistreatment remains common. Torture continues to take place, despite government denials. Many detainees are held indefinitely without knowing the charges against them. Some are held in secret detention. Poor conditions in prisons and jails can be life-threatening.

President Obiang exercises inordinate control over the judiciary, which lacks independence. The president is designated as the country’s “chief magistrate.” Among other powers, he chairs the body that oversees judges and appoints the body’s remaining members.

In February 2014, the Obiang government announced a temporary moratorium on the death penalty. The Community of Portuguese-Speaking Countries (CPLP) admitted Equatorial Guinea on that basis, believing it was a first step toward eliminating the death penalty. Only two weeks before announcing the moratorium, the government executed up to nine people who had been sentenced to death. In July, President Obiang stated in an interview that he continued to support the death penalty.

Agustín Esono Nsogo, a teacher held without charge for over a year, was released in February 2014. According to his lawyer, Esono was tortured on three occasions in an effort to get him to confess to an alleged plot to destabilize the country. He was denied medical attention for his injuries.

Cipriano Nguema Mba, a former military officer who was granted refugee status in Belgium in 2013, was abducted while visiting Nigeria in late 2013 and illegally returned to Equatorial Guinea, where he was secretly held by government authorities and tortured.

This is the second time Nguema was kidnapped from exile abroad. On both ocassions, authorities belatedly acknowledged holding him and claimed he was discovered inside the country and imprisoned to serve an earlier sentence. Following a new trial, in September 2014 Nguema was convicted for an alleged coup attempt and and sentenced to 27 years in prison. His lawyers were not able to visit him and were unable to represent him at trial. Five other people allegedly connected to Nguema were also tried without legal representation, convicted, and handed harsh sentences.

During the year Roberto Berardi, an Italian national, was tortured, held for months in solitary confinement in inhumane conditions, and repeatedly denied medical treatment and access to his lawyer or diplomatic representatives. His family said he was denied food and water for several days in September after a visit to the prison by the ambassador of Equatorial Guinea to Italy, in which she reportedly rebuked Berardi for an open letter he published from jail. Berardi is imprisoned in an apparent attempt to protect his business partner, Teodorín, from disclosures about corruption allegations. President Obiang did not release Berardi on humanitarian grounds, as promised in April under international pressure. He remained in prison at time of writing.

Key International Actors

The United States is Equatorial Guinea’s main trading partner and source of investment in the oil sector. It raised human rights concerns throughout the year. In August, Obiang participated alongside dozens of other leaders in the US-Africa Summit hosted by US President Barack Obama, sparking media controversy that he was permitted to attend despite Equatorial Guinea’s poor record on human rights and corruption. While in Washington, Obiang was also the guest of honor at a dinner and conference organized by the Corporate Council on Africa.

Spain, the former colonial power, eased pressure on Equatorial Guinea to improve its human rights record. In June, Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy attended the African Union Summit outside Malabo, marking the first visit by a Spanish prime minister since 1991. Early in the year, Rajoy had declined to meet bilaterally with Obiang.

Irina Bokova, director-general of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) traveled twice to Equatorial Guinea, including to attend a September prize ceremony hosted by President Obiang for an award he funded and sought to have named after himself. She had previously tried to block UNESCO’s approval of the controversial award.

Equatorial Guinea underwent a second cycle of the Universal Periodic Review at the UN in Geneva and received many recommendations on torture, arbitrary detention, rule of law, freedom of association, press freedom, anti-corruption, and social and economic rights. The government accepted most recommendations and rejected very few. Expectations that this would lead to positive change on the ground are low, however, as the government did not implement changes promised following an earlier UN peer review.