Summary

They rape us because they are in control, because they have guns, because there is nobody to defend us. There is no police or state.

— Survivor from Cité Soleil[1]

Josephine T., 29, and her sister were walking home with some men to the Port-au-Prince neighborhood of Brooklyn on April 15, 2023, when they were stopped by members of the G9 criminal group at a place called Carrefour la Mort, or Crossroads of Death. The G9 members lined up the men and killed some with machetes, others with gunshots. “The criminals cut open some of the men’s bodies before gathering them all together and setting them on fire,” Josephine said.[2] They then raped the two sisters repeatedly. A few hours after Josephine made it home, she learned that her 27-year-old brother was among those who had been killed.[3]

Josephine’s violent experience is not unique. Brooklyn, on the outskirts of Haiti’s capital Port-au-Prince, has been mostly cut off from clean water, electricity, and health care since clashes between the G9 and a rival criminal group, G-Pèp, began in July 2022. Despite the risks, residents have to leave the neighborhood in search of food and to meet other basic needs. The two groups agreed on a truce in late June 2023, which led to a shaky ceasefire, but neighborhoods remain under their control and reports of abuses continue to mount. Residents still struggle to send their children to school, and many can often only eat one meal every two or three days.

The United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH) estimates that criminal groups in Haiti killed more than 2,000 people between January and June 2023, an increase of almost 125 percent compared to the same period in 2022.[4] BINUH also reported 1,014 kidnappings during this time period, as well as “pervasive rape,” as criminal groups use sexual violence to terrorize the population and demonstrate their control. Family members of victims and survivors described suffering or witnessing these and other abuses in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area since January 2023. Various forms of violence have often been accompanied by the burning of homes and looting, forcing people to flee.

The Haitian government has failed to protect people from the violence of criminal groups. To those living in affected areas, the police and other authorities scarcely exist.

In response, some residents have turned to “popular justice,” forming the Bwa Kale movement that gained traction in late April 2023. According to BINUH, as of June 2023 the movement had reportedly killed more than 200 people suspected of being members of criminal groups, often in collusion with police officers.

The dire security situation is exacerbated by intense political deadlock, a dysfunctional judicial system, and long-running impunity for human rights abuses. Prime Minister Ariel Henry has controlled all executive and parliamentary functions since the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021, and he has not reached a consensus with Haitian political actors to enable a democratic transition. Based on available information, there have been no prosecutions or convictions of those responsible for the killings, kidnappings, and sexual violence committed since the start of the year.

Meanwhile, the UN estimates that nearly half of Haiti’s total population of 11.5 million people is acutely food insecure. Over 19,000 people living in the Cité Soleil commune of Port-au-Prince faced catastrophic hunger in late 2022 for the first time on record in Haiti and in the Americas. Haiti is now one of the countries with communities most at risk for starvation, alongside Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Mali, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Yemen. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) elevated Haiti to “the highest concern level” for food insecurity for the period from June to November 2023.[5] In addition, about 5.2 million people currently need humanitarian assistance.

Almost 195,000 Haitians are internally displaced due to violence since 2022, and many others have left the country, often undertaking dangerous journeys they hope will lead to safety. In the first half of 2023, more than 73,000 people were forcibly returned to Haiti, often in abusive conditions, mostly from the Dominican Republic and other countries, despite the high levels of risk to their lives and physical integrity.

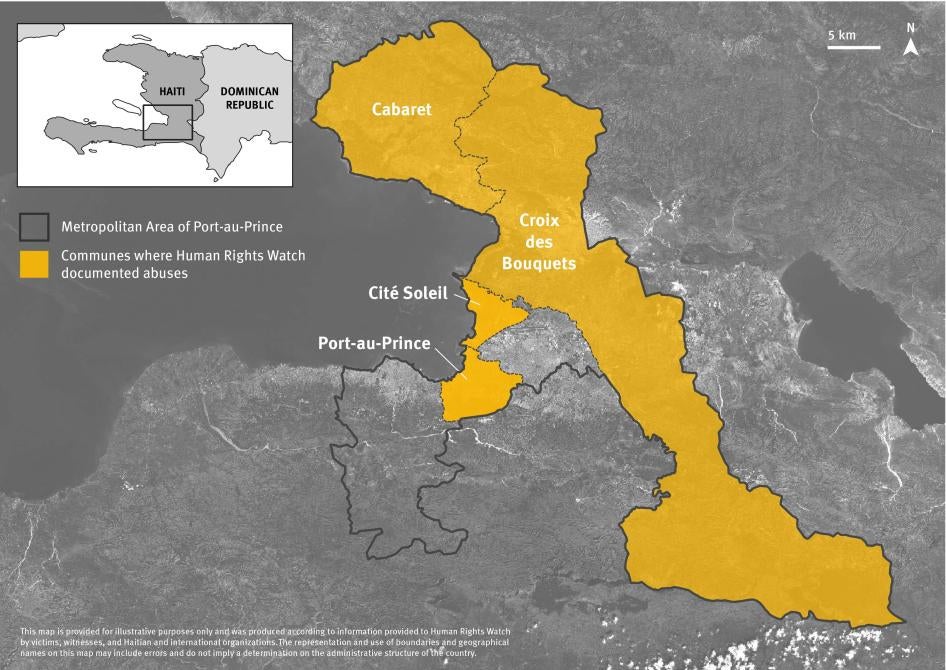

This report documents some of the abuses committed by criminal groups in four communes of the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince—Cabaret, Cité Soleil, Croix-des-Bouquets, and Port-au-Prince itself—between January and April 2023. In total, Human Rights Watch documented 67 killings, including of 11 children and 12 women, and 23 cases of rape, including 19 cases in which victims were raped by multiple perpetrators. This count only includes cases where Human Rights Watch interviewed victims or their family members and other witnesses, and not cases reported by other organizations. Many of those Human Rights Watch interviewed were forced to flee their homes following this round of violence.

The report is based on interviews with 127 people, before, during, and after a Human Rights Watch visit to Haiti in late April and early May 2023. Those interviewed included 58 victims and witnesses of violence, all interviewed in person in Haiti, as well as members of Haitian civil society, human rights and diaspora groups, representatives of the United Nations and humanitarian agencies, Haitian political actors and government officials, including Prime Minister Henry, and international officials working on Haiti. In addition, Human Rights Watch reviewed data and reports by the UN, international nongovernmental organizations, Haitian civil society groups, and the media.

Human Rights Watch also verified 15 videos and 5 photographs of violent incidents and used satellite imagery to geolocate key footage of specific cases in the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince.

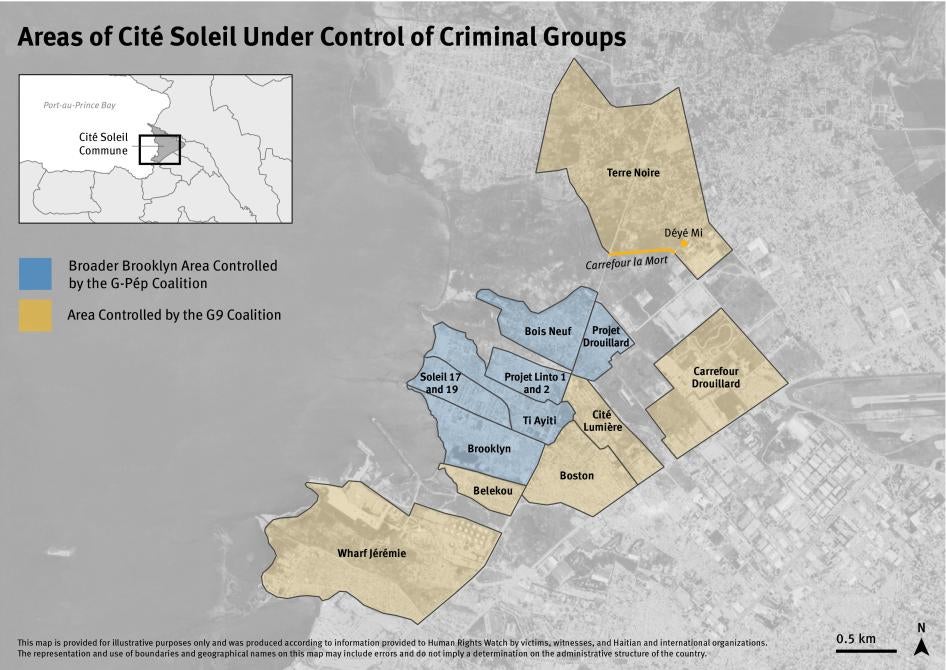

Some of the most egregious abuses occurred in and around the Brooklyn area of Cité Soleil, where Josephine lives. From mid-March 2023, clashes escalated between two of the main criminal coalitions, the G-Pèp federation, which at time of writing controls Brooklyn, and the G9 alliance, which controls all surrounding neighborhoods and is attempting to expand and take control of Brooklyn. The G9 has blocked off all exit routes from Brooklyn, except Carrefour la Mort. Its members positioned themselves there, and during a month-and-a-half of extreme violence from mid-March through late April, routinely shot at, killed, and gang-raped Brooklyn residents trying to go to the city center or return home. Most of the violence occurred at a place known as Dèyè Mi (Behind the Wall). None of the victims from Brooklyn interviewed by Human Rights Watch had denounced the abuses publicly, reported them to the police, or filed judicial complaints because they feared reprisals and lacked confidence in or access to judicial authorities.

This violent struggle for control—fueled by elite and criminal groups’ electoral and economic interests in the area—has severely restricted the ability of Brooklyn residents to access critical services and basic necessities, as markets and health centers have closed. Nearly all victims and witnesses from Brooklyn said they faced daily challenges finding food for their families and living amid filthy wastewater, due to the accumulation of garbage in the city’s sewage canals that run through the neighborhood and into the sea. The G9 cut off electricity approximately two years ago and did not allow water delivery tanks or sanitation workers to enter Brooklyn during the clashes. Some whose homes were burned down in the clashes struggle to find a place to sleep at night.

A community organization working in Brooklyn documented the killings of around 100 people, as well as around 100 instances of sexual violence during the seven-week period in March and April 2023. Since May, only a few sporadic abuses have been reported on Carrefour la Mort and at Dèyè Mi, but violence continues in other parts of Brooklyn due to attacks by G9 members who still surround the neighborhood.

Haiti is party to core human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the American Convention on Human Rights, that protect the rights to life, physical integrity, and liberty, among others. Haitian authorities are obligated to protect these rights effectively, including by taking adequate measures to protect people from reasonably foreseeable threats to their lives by non-state actors, including criminals and organized crime.

In late 2022, Prime Minister Henry called on the international community to deploy a specialized armed force to assist the Haitian National Police in addressing the country’s insecurity. The United Nations secretary-general echoed this call. After months of inaction, the United Nations Security Council on July 14, 2023, gave the secretary-general 30 days to present an options paper, outlining possibilities for a multinational force, peacekeeping operation, or other international response. On July 29, Kenya announced that it would “positively consider” leading a multinational force in Haiti and deploying 1,000 police officers to “help train and assist Haitian police restore normalcy in the country and protect strategic installations.”

Nearly all Haitian civil society representatives and victims of abuse interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the situation has deteriorated so drastically this year that some form of urgent international response is needed to restore basic security and the rule of law and to ensure that all Haitians have access to basic necessities. Many said that the dire security situation and extreme hunger and poverty is worse now than at any time they remember.

Civil society representatives also told Human Rights Watch that meaningful change will likely only happen with the establishment of a new, more legitimate transitional government, ideally led by technocrats who do not have links to criminal groups and who would not run in upcoming elections. They urged that any international force deployed in the country should not in effect prop up Prime Minister Henry, whom they see as heading an illegitimate and corrupt government with alleged links to criminal groups, and the political establishment that accompanies him in power.

Many also highlighted the continuing impact in Haiti of the legacies of slavery, colonialism, racism and anti-Blackness, forced debt, and poverty. They caution that, alongside the historical harms and abuses that resulted directly or indirectly from the intervention in Haiti of outside powers and entities, many Western countries and the UN can still have a significant impact on Haiti’s economy and politics.

Since the early 19th century, when the US, France and other countries refused to recognize Haiti’s independence in order to protect their own slave-owning interests, the country has suffered violent occupation, interference in the control of its public finances and political processes, and forced debt. Haitians in the mid-20th century also endured almost 30 years of dictatorship characterized by violence, corruption, and human rights abuses, during regimes that received support from the US and France. In the 2000s, UN peacekeepers were responsible for sexual exploitation and abuse of women and girls, and a deadly cholera epidemic, which the current cholera epidemic can in part be traced back to.

While those interviewed largely said that some form of international force is now needed to support the Haitian national police in addressing violence, they said that steps must be taken to avoid repetition of past harms and to support implementation of a Haitian-led reparations process.

Human Rights Watch calls on the UN Security Council to heed these calls and, if it authorizes the consensual deployment of an international force in Haiti, ensure that it is based on clear human rights protocols and has adequate funding and robust oversight mechanisms. These should be complemented by strong measures to ensure accountability that include Haitian civil society groups, as well as the provision of humanitarian aid and other basic services to those in need.

Human Rights Watch also calls on the US, Canada, France, Caribbean Community (CARICOM) members and other governments to support the facilitation of the establishment of a transitional government that would work to re-establish rights-respecting rule of law and provide access to basic necessities for all Haitians, until democratic elections can provide the basis for the formation of a regular government.

Urgent action is needed to address the extreme levels of violence, lack of security and near-total impunity, and the palpable feelings of terror, fear, hunger, and abandonment that so many Haitians experience today.

Map

Haiti is administratively divided into 10 departments, which are subdivided into districts, each of which has communes. The communes are in turn divided into community sections, and these are made up of neighborhoods.[6]

According to Haitian and international humanitarian and human rights organizations working in Haiti, this administrative structure may vary and there can be additional or different subdivisions in some places, for example in densely populated or large communes, where residents often refer to subdivisions called “areas” to identify specific zones.

The “metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince” refers to the region encompassing the commune of the capital Port-au-Prince and surrounding areas, including at least seven other communes (Cité Soleil, Croix-Des-Bouquets, Cabaret, Pétion-Ville, Delmas, Carrefour, and Tabarre) that are closely connected and have a total estimated population of 3 million people.[7]

Glossary

BINUH: Bureau Intégré des Nations Unies en Haïti, United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti

CARDH: Centre d’analyse et de recherche en droits de l’homme, Center for Analysis and Research in Human Rights

CARICOM: Caribbean Community

CERP: Center for Economic and Policy Research

EU: European Union

FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization

IOM: International Organization for Migration

MINUJUSTH: Mission des Nations Unies pour l'appui à la justice en Haïti, United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti

MINUSTAH: Mission des Nations Unies pour la stabilisation en Haïti, United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti

MSF: Médecins Sans Frontières, Doctors without Borders

OCHA: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

OHCHR: United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

RNDDH: Reseau National De Défense des Droits Humains (RNDDH), Rezo Nasyonal Pou Defann Dwa Moun, National Human Rights Defense Network

UN: United Nations

UNHCR: United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees

UNDP: United Nations Development Programme

US: United States

WOLA: Washington Office on Latin America

WFP: World Food Programme

WHO: World Health Organization

Recommendations

To the United Nations Secretary-General

- Ensure that BINUH’s activities support the establishment of a transitional government, including through the provision of technical and financial resources and by strengthening interactions with Haitian civil society representatives and political actors (including the opposition) and taking into account their proposals.

- Ensure that OHCHR, BINUH, and other UN agencies support the implementation of a vetting mechanism for the Haitian National Police, under the authority of the transitional authorities, with the goal of identifying, investigating and as appropriate prosecuting, police officers implicated in human rights violations, corruption, support to criminal groups, or other crimes.

- Ensure that OHCHR and other UN agencies work to provide training and technical support to a specialized pool of Haitian judicial investigators, prosecutors, and judges focused on ensuring accountability—including for crimes by members of violent criminal groups and police officers, politicians, and others supporting them—with a view toward reform of the judicial system.

- Support the implementation of measures to address the humanitarian situation and severe overcrowding in prisons, primarily because individuals are held for extensive periods in pre-trial detention, and to have prisons where members of criminal groups allegedly responsible for serious abuses, and their supporters, can be detained in secure and humane conditions.

- Support efforts to ensure that those arrested or detained for their alleged involvement in criminal acts are guaranteed rights-respecting trial procedures that include access to legal counsel and deprivation of liberty only as a last resort; a humane, rights-respecting, and functioning pre-trial facility; a rights-respecting criminal trial process that includes the right to judicial review; and a functioning prison with humane conditions.

- Support the provision of trauma-informed specialized health care, legal support, and psychosocial support, including during criminal proceedings, for survivors of sexual violence, including through support to Haitian organizations.

- Work with the transitional government to implement specialized programs for the disarmament, demobilization, and social and economic reintegration of people associated with violent criminal groups, with special attention paid to trauma-informed support for children associated with such groups.

- Rigorously apply the Human Rights Due Diligence Policy to any planned cooperation with the Haitian National Police and other security forces in the country.

To the United Nations Security Council

- Any authorization of the consensual deployment of an international force, as requested by Haitian authorities and the UN secretary-general, should be primarily composed of police officers and should support the Haitian National Police’s efforts to restore basic security. The force should be mandated to patrol and secure access to the country’s main roads to ensure the transport of food and humanitarian aid and to allow residents to circulate freely; secure key locations such as ports, airports, courts of justice, and hospitals to allow services to be provided to the population; and provide technical, logistical, and intelligence support to the Haitian authorities as they seek to investigate, arrest, and prosecute abusive leaders of criminal groups and those backing these groups through rights-respecting procedures, including by creating conditions to allow members of these groups to safely surrender their weapons. The Security Council should also:

- Require the creation of an independent mechanism, with the involvement of Haitian civil society groups, to monitor and report on the international force’s conduct and performance. This mechanism should include a plan to publicize its existence to the Haitian public; accessible, confidential, and independent complaints procedures for the public; an independent investigation branch with a gender perspective; and procedures to share evidence with other countries’ judicial systems to better ensure accountability in the countries of origin of forces responsible for breaches of international norms and UN codes of conduct.

- Reiterate the expectation that the force’s leadership will not tolerate misconduct of any kind, including sexual exploitation and abuse by the force; will promptly investigate all allegations of misconduct; and will appropriately address incidents of confirmed misconduct.

- Remind the United Nations that it must rigorously apply the UN’s Human Rights Due Diligence Policy and refrain from cooperating with units or commanders of the international force or the Haitian National Police that have credibly been implicated in serious human rights abuses or support to criminal groups.

- Urge robust efforts led by Haitian entities focused on: investigating and prosecuting those most responsible for serious violent crimes; resolving the country’s political deadlock and facilitating a transitional government; ensuring the safe delivery of urgent humanitarian aid and access to other basic services; curbing the flow of weapons and ammunition to violent criminal groups; and providing jobs, education, and other opportunities for those in communities previously controlled by violent criminal groups.

- Expand the existing arms embargo to include a prohibition on all weapons and materiel transfers to Haitian territory, with an exemption for the Haitian National Police, as long as a strict control mechanism is implemented to ensure delivery and non-diversion.

- Direct the Panel of Experts to produce a specific report to identify states and other actors that violate or circumvent the arms embargo with a special focus on transfers of small arms.

- Impose further targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, on those responsible for killings, kidnappings, sexual violence, and other serious abuses, as well as those Haitian and foreign actors responsible for providing support to abusive criminal groups.

- Request regular 30-day reporting from the UN secretary-general on the situation in Haiti.

- Urgently call for a briefing about Haiti by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on sexual violence in conflict; and for the immediate deployment of a women’s senior protection advisor who should work closely with BINUH, OHCHR, and other UN agencies.

To all concerned Governments, Institutions, and Donors

- Stop supporting political actors in Haiti who are credibly implicated as responsible for supporting criminal groups.

- Support, including through technical and financial resources, facilitation of the establishment of a transitional government to restore basic security and ensure adherence to fundamental human rights, re-establish rights-respecting rule of law, and provide access to basic necessities for all Haitians, until the formation of a regular government on the basis of democratic elections.

- Call for any consensual deployment of an international force to be based on clear human rights protocols, have adequate funding and robust oversight mechanisms, and be complemented by strong measures to ensure accountability, curb the flow of weapons and ammunition to violent criminal groups, and provide humanitarian aid and other basic services, education, and jobs in areas that have been most affected by violent criminal groups.

- Support efforts by the transitional government and any international force to effectively dismantle criminal groups and their criminal networks by ensuring that those responsible for large-scale killings, sexual violence, and kidnappings, and for providing support to criminal groups, including outside Haiti, are held accountable through rights-respecting procedures. Such support should include steps by foreign governments to examine and improve their domestic actions to address any links existing in their own countries to violent criminal groups operating in Haiti.

- Ensure that immigration policies and measures comply with international human rights laws, in particular with the non-refoulement principle, and where such policies and measures exist, keep them in place and expedite their implementation to achieve protection for Haitians. All governments, particularly the Dominican Republic, the United States, the Bahamas, and Cuba, should stop removing, expelling, or deporting people to Haiti as long as conditions of violence and other exceptional conditions present a real risk of serious harm. This suspension of returns should include children born of Haitian parents abroad who face a high risk of violence in Haiti and have no effective access to protection or justice.

- Consider directing additional emergency humanitarian aid to Haiti, in particular toward strengthening the functioning of humanitarian agencies to ensure that Haitians can freely receive this assistance and access basic services while a transitional government puts in place a sustainable plan of assistance for those in need. Ensure measures are in place or improved to guard against sexual exploitation in the delivery of all services and assistance.

To the United States, Canada, and the European Union

- Impose, fully enforce, continuously update, and adopt additional targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, against those responsible for killings, kidnappings, sexual violence, and other serious abuses, as well as those Haitian and foreign actors responsible for providing support to abusive criminal groups, as necessary, to ensure they are tailored to evolving circumstances in Haiti.

- Adopt stronger measures to stop the illicit flow and sale of weapons and ammunition to violent criminal groups operating in Haiti.

To the United States and France

- Explicitly recognize, with guarantees of non-repetition, the responsibility of the US and France for their historic harms and abuses with ongoing impacts and work towards the development of an effective and genuine reparations process led by Haitian people.

To Members of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM)

- Continue supporting political negotiations among Haitian civil society representatives, political actors, and government officials towards the establishment of a transitional government that should work to restore basic security and ensure adherence to fundamental human rights, re-establish rights-respecting rule of law, and provide access to basic necessities for all Haitians.

- Adopt measures to stop the illicit flow and sale of weapons and ammunition to violent criminal groups operating in Haiti, including strengthening control of seaports and maritime traffic.

To Prime Minister Ariel Henry’s Administration

- Engage meaningfully and urgently with a diverse group of Haitian social and political actors to craft a solution to the country’s multifaceted crisis with clear objectives and a precise timetable.

- Support a process that will allow a transitional government to form, reestablish basic security and ensure adherence to fundamental human rights, re-establish rights-respecting rule of law, provide safe and fair access to basic necessities for all Haitians, and hold democratic elections to establish a regular government.

- Work to ensure that all Haitians have access to basic services, including health services, justice and reparations for survivors of sexual violence, ensuring those living in areas controlled by criminal groups are not left out.

- Support efforts to sanction and hold accountable through rights-respecting procedures those responsible for large-scale killings, sexual violence, and kidnappings—including the attacks in Cité Soleil, Source Matelas, Bel-Air, and Croix-des-Bouquets documented in this report—as well as those who have provided support to abusive criminal groups.

- Do not criminalize children who have been coerced or forced into criminal groups’ activities and support measures aimed at their rehabilitation and reintegration.

- Urgently address the crisis in the judicial system, including by relocating courts to safe areas, providing security for threatened judicial officials, improving prison conditions, and urgently improving access to justice for all Haitians.

- Remove abusive or corrupt officers and officials from the police force and judiciary.

- Work with the international force (if deployed), the National Police, and international partners to restore basic security in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area, as well as other parts of the country plagued by insecurity.

- Work with UN agencies and donors to provide assistance to people who are displaced internally due to violence and natural disasters.

- Work with UN agencies and donors to implement a comprehensive returnee reintegration program for those who have already been removed, expelled, or deported to Haiti that addresses their specific needs, including work, security and family reunification, services for survivors of gender-based violence, and support for children on the basis of a best interests assessment.

- Establish a dialogue with the government of the Dominican Republic to address its treatment of Haitians and their descendants and implement assistance programs for those affected.

Methodology

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch interviewed 127 people, before, during, and after a visit to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, from April 27 to May 5, 2023. Interviews were conducted in English, French, and Creole with the support of Haitian translators and humanitarian and human rights workers. Additional meetings took place in Washington, DC with diaspora groups and Haitian and US government officials between March and June.

Those interviewees included 58 victims and witnesses of various forms of violence, people who were injured, and relatives of those who were killed or faced sexual violence. All were interviewed in person in Haiti. We also interviewed representatives of Haitian civil society groups and political coalitions, and human rights and community organizations working in Haiti; members of the diaspora; representatives of international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), international organizations and the United Nations; and experts. We met with Haitian government officials, including Prime Minister Ariel Henry and Ambassador Leon Charles, Permanent Representative at the Organization of American States (OAS), as well as government commissioners and judges.

Human Rights Watch reviewed data and reports by the UN, the United States government, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), international NGOs, Haitian and diaspora civil society groups, and the media.

In addition, we used satellite imagery to geolocate eight videos shared on social media showing attacks committed by the Bwa Kale movement, mainly in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area. We also verified 12 videos and photographs showing the catastrophic humanitarian situation faced by the Haitian population in the Port-au-Prince area.

Our documentation of the killings and cases of sexual violence is based mostly on information provided by victims or their family members and witnesses to events, cross-checked with information collected by Haitian and international human rights and community organizations. Because criminal groups burned the bodies of many of the victims, and due to the limited access to health care and lack of a functioning judicial system, it was difficult to obtain medical records, autopsy reports, or death certificates. Most of the victims and witnesses Human Rights Watch interviewed either did not have access to smartphones or were too afraid to use them to record violence and abuses, which limited the availability of photographs and videos.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed Haitian and international security experts and analysts, human rights officials, and government officials about their own research into alleged links between violent criminal groups and the country’s political, economic, and security elite. We did not have the capacity to independently verify claims about these alleged links.

Human Rights Watch identified victims and witnesses of violence with the support of Haitian human rights and community groups and international organizations. We also visited a hospital in Port-au-Prince.

Human Rights Watch has used pseudonyms for most interviewees, as they requested confidentiality for fear of reprisals.

Human Rights Watch informed all participants of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which information would be collected and shared publicly. Interviewers assured participants that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions, without any negative consequences. All interviewees provided informed consent orally and, in the cases where recordings of their testimonies were made, they gave their written consent.

Interviews were semi-structured and covered topics related to abuses by criminal groups, the humanitarian situation, the political, judicial and security context, and the international response.

No interviewee received compensation for providing information. Human Rights Watch only provided financial assistance for transportation and food to those interviewed who needed it, through the human rights and community organizations that helped locate them. We also referred several survivors of sexual violence to a hospital where they could receive medical attention free of charge, and supported the foreseen transport costs. Care was taken with victims of trauma to minimize the risk that recounting their experiences could further traumatize them.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the Haitian National Police, the Ministry of Justice, and Prime Minister Ariel Henry on July 12, laying out allegations of police inaction during or complicity in violence in the attacks that took place in Cabaret and Port-Au-Prince communes, and the violence committed by the self-defense groups known as the Bwa Kale movement. At time of writing, we had not received a response.

Haitians and international observers refer to those responsible for the abuses that Human Rights Watch documents in this report as members of gangs, armed groups, or violent criminal groups. For the purposes of this report, we are using the term criminal groups or violent criminal groups.

I. Soaring Insecurity

The security situation in Haiti has deteriorated drastically as violent criminal groups have expanded their areas of control, committing serious human rights abuses and disrupting the social and economic lives of Haitians. This has led some Haitians to form new self-defense movements, exacerbating a spiral of violence that the authorities have not been able to address. The abuses documented by Human Rights Watch in four communes of the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince amount to serious violations of international human rights law that should be investigated and prosecuted in fair and credible judicial proceedings.

Applicable Legal Standards

Haiti is party to core human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the American Convention on Human Rights, that protect the rights to life, to physical integrity, and to liberty, among others. Haitian authorities are obligated to protect these rights effectively, including by taking adequate measures to protect people from reasonably foreseeable threats to their lives by non-state actors, including criminals and organized crime.[8]

Killings, Sexual Violence, and Kidnappings by Criminal Groups

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimates that approximately 300 criminal groups operate in Haiti, half of them in the West department that includes the capital Port-au-Prince and its metropolitan region, where they killed more than 2,000 people during the first half of 2023, an increase of nearly 125 percent compared to the first half of 2022. Six hundred were killed just in April.[9]

Most of the killings took place in communes and neighborhoods that are largely under the control of criminal groups, including Cité Soleil and Bel-Air, while some took place in Cabaret, Croix-des-Bouquets, and other areas where criminal groups have recently expanded their control.[10]

In Cité Soleil, long-running clashes intensified in mid-2022 between the two main criminal coalitions, the G-Pèp federation, led by Gabriel Jean-Pierre, alias “Gabriel,” and the G9 alliance, led by Jimmy Chérizier, alias “Barbecue.” In other areas, both criminal groups that are part of these coalitions and independent groups have sought to expand their territorial control, directly attacking the population and establishing themselves as the de facto authorities, including in neighborhoods considered relatively safe or free of criminal activity in previous years.[11]

Haitian human rights organizations and international organizations assess that criminal groups currently control nearly all of the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince, an alarming expansion compared to December 2022, when these organizations estimated that criminal groups controlled 60 percent of this area.[12]

Violence has also spread to other parts of the country, including the neighboring Artibonite department to the north, a largely agricultural region. According to international and Haitian humanitarian and human rights organizations, some criminal groups, mainly Baz Gran Grif, led by Luckson Élan, alias “Jeneral Luckson,” have expanded their territorial control in the communes of Deschapelles, La Croix Périsse, L’Estère, Liancourt, Petite Rivière de l’Artibonite, Saint Marc, and Verrettes. This expansion led to at least 123 murders between January and June 2023, an increase of about 485 percent compared to the same period in 2022, as well as the closure of multiple markets and abandonment of land, which affected food production and the distribution chain to Port-au-Prince and from there to the rest of the country. This has severely aggravated the food insecurity crisis that now affects almost half of Haiti’s population.[13]

Killings in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area and Artibonite are often accompanied by sexual violence, looting, burning of corpses in the streets, and burning or illegal occupation of houses, all of which have led to the displacement of thousands of people.[14]

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), between January and June 2023, more than 47,400 people were newly displaced in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan region, and more than 6,700 in Artibonite, including people who arrived from the Cabaret, Croix-des-Bouquets, and Port-au-Prince communes in the West Department, due to violence.[15]

Sexual violence, including gang rape, continues to be used by criminal groups to terrorize, control, and “punish” women and girls who live in areas controlled by rival criminal groups.[16] International organizations also reported abuse and sexual exploitation by criminal groups of women and children living in areas under their control.[17]

In Cité Soleil, some criminal groups, including members of the G9 alliance, gang-rape women and girls living in neighborhoods controlled by the G-Pèp federation to instill fear, as part of their effort to gain control of the area. Other groups use sexual violence as a form of control to demonstrate that they are the new authority in areas where they previously had no presence, and still others use it as punishment for residents who oppose their presence in the neighborhoods.[18]

“Sexual violence is not only used as a weapon of war between criminal groups,” an international humanitarian officer told Human Rights Watch. “But it has become a usual practice, just for their [criminal group members’] pleasure, simply because they have the power to do so, since they have control of the population in the absence of the state.”[19]

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, Doctors Without Borders), which runs several hospitals in Port-au-Prince, reports that between January and May 2023, it assisted a total of 1,005 survivors of sexual violence in Port-au-Prince, almost twice the number registered during the same period in 2022.[20] The Haitian women’s rights organization Négés Mawon has documented more than 110 cases of sexual violence committed by criminal groups since the start of the year.[21] However, underreporting is significant, and no state or nonstate entity keeps track of the total number of cases.[22] Of the 23 people whose sexual violence cases Human Rights Watch documented and which occurred between January and April 2023, 16 said they had not received any medical treatment before Human Rights Watch met with them and referred them to a hospital.

Criminal groups also kidnapped more than 1,000 people in the first half of the year, often only releasing victims after receiving hefty ransom payments.[23] This is an increase of almost 49 percent compared to 681 reported kidnappings in the same period in 2022.[24] The victims are primarily Haitian nationals, and include civil servants, judicial officials, health and education workers, and others perceived to have access to financial resources, as well as some who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.[25] Some foreigners have also been kidnapped, including 40 in the first half of 2023.[26] In some cases, assailants reportedly sexually assaulted victims of kidnapping to pressure families to pay the ransom.[27]

According to several international and Haitian human rights officials and security experts monitoring the situation, kidnapping has reached new levels of severity and has become one of the main sources of financing for criminal groups, and giving them more autonomy and strength, and helping facilitate their territorial expansion.[28] “It’s a business,” a Haitian civil society representative said. “It allows them to get food and buy weapons and ammunition. Kidnapping is the only business that’s functioning in Haiti today.”[29]

Children have been particularly affected by the violence. The UN secretary-general’s annual report on children in armed conflict, published on June 27, 2023, added Haiti as a “situation of concern with immediate effect,” due to “the gravity and number of violations” between September 2022 and March 2023, including “recruitment and use, killing and maiming, rape and other forms of sexual violence, attacks on schools and hospitals, abduction, and denial of humanitarian access.”[30]

Rise of a Violent “Self-Defense Movement”

Given the alarming insecurity and the state’s failure to protect residents, some Haitians have decided to take “justice” into their own hands, forming what has become known as the Bwa Kale movement. Justice Minister Émmelie Prophète-Milcé appeared to encourage this when she stated in a press release in March 2023 that the criminal code allows for legitimate self-defense.[31] The Bwa Kale movement gained traction on April 24, 2023, when residents of Canapé-Vert, a neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, took 14 suspected members of criminal groups from police custody, lynched them with improvised weapons, and burned their bodies in the street as police officers looked on and, in some cases, appeared to encourage the residents.[32] A video recorded in Canapé-Vert on April 24 and shared on Twitter shows one police officer stepping on a person’s back to keep him on the ground while residents throw rocks at him and other suspected criminal members moments before they are set on fire.[33]

Since then, the movement has expanded to at least eight departments and resulted in the killing of more than 200 suspected criminal group members, according to the United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH) and the Center for Analysis and Research in Human Rights (CARDH), a Haitian nongovernmental group.[34] Some victims were apparently targeted because they seemed unfamiliar to neighborhood residents or had tattoos or dreadlocks, or because their photos had been posted on social media.[35] Human Rights Watch verified eight videos uploaded to social media and news sites between April 24 and May 19, 2023, showing four different attacks relating to the Bwa Kale movement.[36] Three of the attacks documented in these videos took place within 15 meters of police stations.

While kidnappings by criminal groups reportedly decreased in some areas, apparently due to this movement, according to CARDH, attacks have continued unabated in other areas. Many residents unaffiliated with Bwa Kale fear violent reprisal attacks by criminal groups and a further spiraling of the situation, particularly as members of criminal groups have formed their own new movement in retaliation, known as Zam Pale.[37]

A Haitian human rights representative told Human Rights Watch:

The self-defense brigades seize weapons from alleged members of criminal groups, but they are not handing them over to the police. They are using them, and now they are asking the neighbors for money for ammunition, gasoline, etc., following the same pattern of formation of the criminal groups.[38]

An international humanitarian worker warned: “We’re talking about groups of up to 50 residents and they’ve started asking residents for money to protect them... It’s very dangerous because many innocent people are victims... and if people refuse or tell them that they are also violating human rights, they accuse [their critics] of defending the gangs and threaten them.”[39]

The UN secretary-general warned in a report on July 1, 2023, that the Bwa Kale and Zam Kale movements have “sparked a new and alarming cycle of violence which, if not urgently addressed, is likely to escalate through further mobilization, arming, and recruitment, especially of youth.”[40]

Port-au-Prince Communities Most Affected by Violence

Between January and April 2023, many of the most egregious abuses took place in four communes in the West department, all in the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince: Cité Soleil, Cabaret, Port-au-Prince, and Croix-des-Bouquets. Human Rights Watch documented some of these abuses: 67 killings of residents by members of criminal groups, including 11 children and 12 women, and 23 cases of rape, including 19 cases of gang rape, where the victims were sexually assaulted by multiple perpetrators. These figures only include cases where Human Rights Watch interviewed victims or their family members and other witnesses, and not cases we heard about from other organizations. Many of those Human Rights Watch interviewed were forced to flee their homes following this latest round of violence.

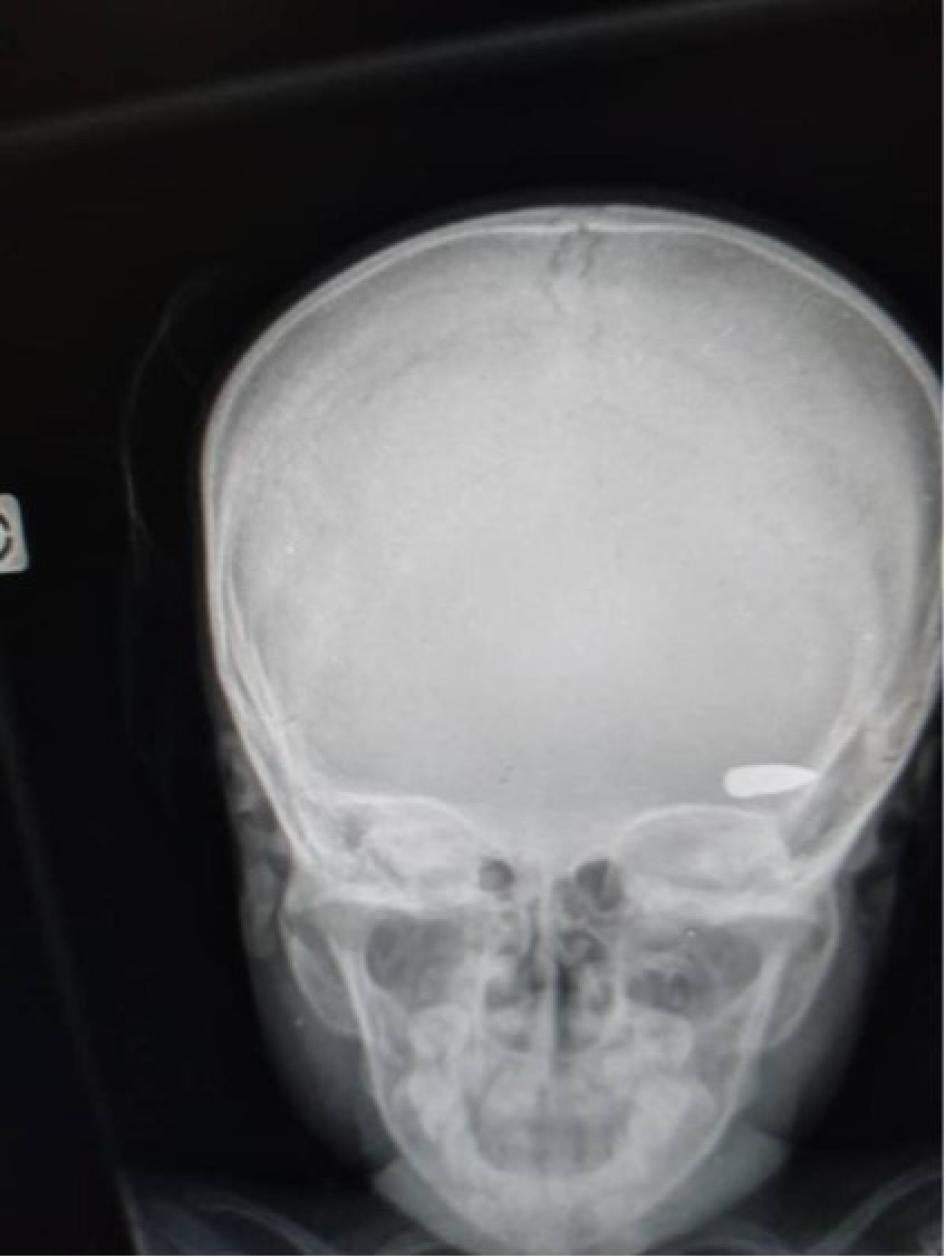

At least 45 victims died from gunshot wounds, while others were attacked with machetes, and some were burned alive inside their homes. Most of those shot were hit in the head, chest, or back, and appear to have been targeted. Two were apparently victims of stray bullets while they were inside or just outside their homes, and one victim was shot while fleeing during clashes between different criminal groups. In a few cases, family members were able to recover the bodies of their loved ones for burial. Most bodies, however, were burned in the streets or taken away by the criminal groups.[41]

Many survivors of rape said that they were also beaten during the episodes of sexual violence, and one said the perpetrators penetrated her vagina with a stick. Sixteen of the victims had not visited a health center or received any medical care before Human Rights Watch met with them and referred them to a hospital for treatment. Ensuring prompt access to health care for sexual violence survivors is critical because some treatments are time-sensitive, such as emergency contraception to prevent unintended pregnancy and post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection.[42] Some survivors interviewed for this report did not have access to these treatments. Many described the continued physical pain, psychological trauma, and stigmatization that they endured after the assault.

One woman from Bel-Air said that she was held captive by members of a criminal group for five days in late February and early March 2023, during which five men repeatedly raped and beat her. Another woman from Bel-Air said she became pregnant after being gang-raped in February 2023.[43]

Killings and Sexual Violence on the Crossroads of Death, Cité Soleil

Human Rights Watch interviewed 21 victims and witnesses, mostly from the Brooklyn area, who described how they or their loved ones were killed, raped, or injured between mid-March and late April 2023 by members of the G9 on a block known as Carrefour la Mort (Crossroads of Death), and at a nearby point known as Dèyè Mi (Behind the Wall), on the only open road that connects Brooklyn to the rest of Port-au-Prince. A community organization documented the killings of more than 100 people and over 100 cases of sexual violence at these locations during this period.[44]

Human Rights Watch documented 35 killings in this area, including of 6 children, and 17 cases of sexual violence. In addition, five people injured by gunshot at Carrefour la Mort were interviewed while being treated at a hospital in Port-au-Prince.

“Brooklyn residents are living a nightmare,” a community organization representative told Human Rights Watch. “They only have one way to enter and leave the area that they need to use daily to make a living… But when they arrive at the place known as Carrefour la Mort, members of the G9 indiscriminately shoot at them or gang-rape women and girls behind the wall, known as Dèyè Mi.”[45]

Brooklyn has for several years been strategically important for criminal group leaders and their backers, including political and economic actors: it is a significant electoral base with an estimated population of more than 100,000 people, and its location on the coast and proximity to ports means that controlling it brings economic benefits.[46] The area has been controlled in recent years by the Gang of Brooklyn, part of the G-Pèp federation led by Gabriel Jean-Pierre (“Gabriel”). The neighborhood is surrounded by areas controlled by other criminal groups that are all part of the G9 alliance and in conflict with the G-Pèp, including the Gang of Belekou (led by “Isca”); the Gang of Boston (led by “Mathias”); and the Gang of Warf Jérémie (led by “Micanor”), which controls the port area.[47] Other members of the G9 also operate in other neighborhoods surrounding Cité Soleil, including the Gang of Terre Noir, the Gang of Simon Pele, and the Gang of Drouillard.[48]

For several years, residents of Brooklyn and other areas controlled by the G-Pèp have been besieged and attacked by G9 members who want to gain control of all of Cité Soleil.[49] These attacks escalated in the second half of 2022, starting with a particularly deadly incident on July 8, when at least 95 people were killed in the Soleil 9 and Sous Terre sectors of Brooklyn, according to the United Nations.[50] Between July and December 2022, the UN estimates a total of 263 killings, 285 injuries, 57 cases of sexual violence, and 4 disappearances occurred in Brooklyn alone. Thousands of people were displaced.[51]

The attacks escalated dramatically again in mid-March 2023. Victims from Brooklyn whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said they had been targeted by the G9 because they live in an area controlled by its rival.

Anne J., a 34-year-old Brooklyn resident, told Human Rights Watch:

The rapes and killings happen every day at Dèyè Mi…. [T]he bandits have us cornered. When we have to go out to look for food or money, they rape and shoot us; there is no police or anyone to help us.[52]

In mid-April 2023, Anne said she lost her older brothers, ages 40 and 50, when they were trying to leave the neighborhood to go to work. Both were shot dead by G9 members at Dèyè Mi. Anne was sexually assaulted by five men at the same place:

They dragged me by the hair to an abandoned house, where five men raped me one after the other… They told me that this was happening to me because I was one of Gabriel’s women [referring to the leader of the G-Pèp] … My 29-year-old sister was also raped on the same day by three G9 members.[53]

Aurelie F., a 17-year-old resident of the Soleil 1 sector of Brooklyn, said she was sexually assaulted at about 1 p.m. on March 22 at Dèyè Mi, when she was returning home after shopping:

They grabbed me, raped me, and hit me in the face. Another one held me with both hands because I resisted... I was brutally raped and now I am injured. I could not walk for six days. I have not been able to go to the hospital .... My mom has no money. Every time I think about this, I cry a lot. [54]

Natalie P., a 42-year-old mother of three, was crossing Dèyè Mi on her way home from the market at around 7 p.m. on April 16, 2023, when criminals called out to her. She tried to keep going, but then they shot in her direction. “I wasn’t hit, but then they caught up with me and tore off my clothes… They beat me with their guns, and then five of them raped me,” she told Human Rights Watch.[55]

Two days later, Natalie’s 16-year-old son was shot and killed. Natalie said her son was hit in the chest by a bullet when he got caught in a clash between the G9 and G-Pèp on his way home from school:

This clash between the G9 and G-Pèp is what prevents us from living… The bandits are in position, and they fire on members of the population. When we’re wounded, there’s no hospital. There’s only one road into the area, and there’s a pile of bodies there. We try to go out before 4 a.m. because we know that after that, the bandits will come out with a vengeance. It’s a really complicated situation. To leave our neighborhood, we have to do it in hiding. And to return home, it’s the same thing… The situation is really extreme. We want to leave the area, but we don’t have the means to live elsewhere. So, we have to stay... Just since April 15, lots of women were raped, and lots of people were killed.[56]

Natalie also said she saw a pile of bodies at a house right next to Dèyè Mi, on around April 20:

The bodies were piled on top of each other. Lots of people were killed, and lots of crimes were committed. Some people were mutilated, some were killed by bullet, and some were chopped up by machete.[57]

Camille M., a 29-year-old mother of three from Brooklyn, lost her husband on April 1, 2023, when G9 members took him away at Dèyè Mi while he was on his way home after looking for work. On April 2, 2023, she went out to sell rice, peas, and oil in the market to try to earn some money, and was stopped at the same point on her way home. Camille was beaten in the face with a bat and raped by four criminals.[58] “When they finished, the bandits told me to leave quickly,” she said. “But it was hard for me to walk.”[59]

Camille’s 26-year-old sister was killed on April 15, when G9 members attacked Gabriel’s group in Brooklyn’s Soleil 17 sector, in an apparent attempt to take control of the area. “She was at home,” Camille explained. “There were gunshots, and then she was shot in the head and died. Many people were killed that day. Some of the bodies were burned, some were decapitated, and some were chopped up,” she told Human Rights Watch.

Camille said she later saw her sister’s body among a pile of dozens of bodies on the side of the road at Dèyè Mi:

[They] were all on top of each other. There were women and men. Some were decapitated, some had their breasts cut off, or their arms or legs cut off. They were all people who lived in the area who had been killed recently.[60]

Julieth F., a 30-year-old mother of four children, lost her 37-year-old husband in mid-April 2023 when they were returning to Brooklyn after selling merchandise on the street:

When we were walking along the street we call Carrefour La Mort, we were approached by three men … They raped me… Another armed man took my husband … They killed him and then burned his body. I saw them drag him to a pile of bodies, they placed some tires on top, and then set them on fire.[61]

None of the victims from Brooklyn interviewed by Human Rights Watch had denounced the abuses publicly, or filed police or judicial complaints, because they feared reprisals and lacked confidence in or access to the police and judicial authorities. The police station in Cité Soleil has not been operational since June 2021.[62] Port-au-Prince’s judicial authorities have not initiated any preliminary investigation into the abuses in Brooklyn or on Carrefour la Mort, Haitian human rights organizations said.[63]

Two survivors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were directly warned by G9 members not to speak publicly about what they experienced or witnessed.

Clementine V., a 33-year-old mother of four children, was beaten in the face and raped by two men on April 20, 2023, at around 4 a.m. in Dèyè Mi when she went out to sell products at the market. With her was her 32-year-old sister, a mother of three children, whom the bandits killed because she resisted the sexual violence. “When the women obey, they aren’t killed, but if they resist, they’re killed,” Clementine told Human Rights Watch:

[My sister] was shot... They burned her in my presence and her corpse was placed in a pile with other corpses. Then they let me go, but they told me not to say anything about what had happened to the press. Otherwise, they would kill me.[64]

Mathilde F., a 36-year-old mother of four children from Projet Linto 2 sector in Brooklyn, said she saw on April 19, 2023 how her 38-year-old brother was killed by G9 members at Dèyè Mi:

We were intercepted by armed criminals. One of them took a knife and stabbed my brother in my presence… they pulled out his organs. Then three of them raped me.... When they finished raping me, they ordered me to run away. They told me that they had left me alive so that I would tell others what had happened.[65]

But Mathilde said they also warned her that if she ever spoke to the press, they would kill her.[66]

A few cases of killings and sexual violence have been reported on Carrefour la Mort since early May, when G9 members apparently began to allow Brooklyn residents to circulate without attacking them, although the G9 still surrounds the neighborhood. More killings and cases of sexual violence were reported in May and June inside Brooklyn, when members of the G9 who control the neighboring Boston and Belekou areas, carried out attacks and incursions, in some cases accessing some Brooklyn streets.[67]

A community organization representative told Human Rights Watch in early July that it appeared that G9 and G-Pèp leaders had reached a truce on June 28. However, the representative added: “We don’t know why or how long it will last. The underlying situation has not changed for Brooklyn residents. They are still afraid of attacks and continue to suffer from hunger and thirst and live amid mud and sewage.”[68]

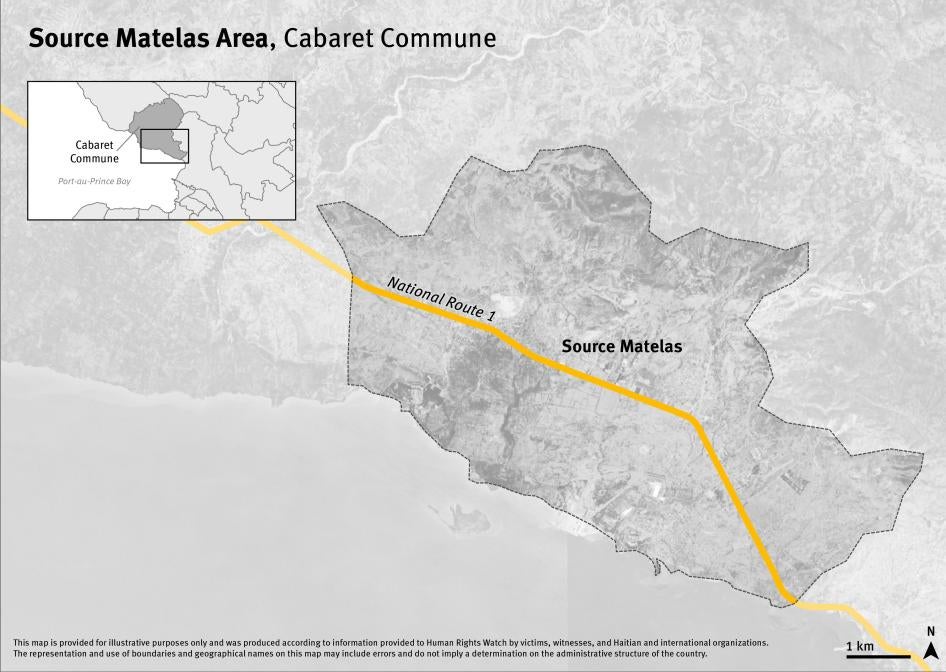

Reprisals Against Residents in Source Matelas (Cabaret)

On April 19, 2023, members of the G-Pèp federation launched a five-day attack on the Source Matelas area in Cabaret commune, apparently to punish the population for having built barricades to prevent criminal groups from attacking and taking control of their neighborhood.[69] Human Rights Watch estimates that at least 130 people were killed, 20 homes were looted and burned, and more than 3,700 people were forced to flee their homes, based on interviews with Haitian and international human rights officials who investigated the attack and a review of public and confidential reports by an international organization that documented the incident.[70] Human Rights Watch interviewed five victims and witnesses from this five-day attack and documented the killings of seven people, six of whom were burned in their homes, as well as three cases of sexual violence.

Three G-Pèp groups were involved in the April attack, including those led by Jean Auguste Cherisme, alias “General Bogi”, Bigel Chery, alias “Big C”, and Jeff Larose (“Jeff”), Haitian activists and researchers said, based on victims’ testimonies and information provided by local residents that identified the perpetrators as members of these groups.[71]

Approximately 2,000 people live in Source Matelas, a strategic and profitable location for criminal groups, given its location just to the north of Port-au-Prince along the national road connecting the capital with the country’s northern departments.[72] G-Pèp members previously attacked the population of Source Matelas in November 2022, in another apparent attempt to gain control of the area. During that incident, 72 people were reportedly killed, 29 women and girls were raped, and over 1,400 people were displaced, according to Haitian human rights groups.[73]

Five witnesses of the attack in 2023 told Human Rights Watch that some assailants arrived in Source Matelas shooting indiscriminately. Others, armed with machetes and long rifles, forcefully entered homes, killed and burned residents inside, shot those fleeing, and sexually assaulted women on the street in an apparent effort to spread fear and send the message that they were the new authority in the area. Even though there was a police presence in the area, witnesses said the police officers did not intervene to prevent or stop the attack.[74]

Human Rights Watch presented these findings to the Haitian National Police and requested a response to the allegations of non-intervention in a letter on July 12, 2023, but had not received a reply as of August.

Cecile Z., a 31-year-old mother of a 6-month-old baby, said she was sexually assaulted on April 19, 2023. She described how she was at home in Source Matelas when members of criminal groups arrived and started “firing everywhere.” She ran out, hoping to flee to safety:

I saw lots of people who were killed, and I didn’t know which way to go. Then I passed armed men with masks; I couldn’t see their faces. They then forced me to the ground, and even though I had my period, three of them raped me… They put the baby on the ground, and she cried while they attacked me. They also put their hands around my throat. When they finished, they started to fire their guns and I took advantage of this to take the baby and run. … I’ve had a lot of pain in my stomach since then.[75]

Cecile later learned that her 77-year-old grandfather and her cousin, seven months pregnant, were burned to death in her home, along with another cousin who lived nearby and whose house was also burned. “I lost everything,” she said.[76]

Marie N., a 32-year-old resident of Source Matelas, said her 74-year-old father and 15-year-old nephew were killed by criminals on April 19, 2023:

The criminals were on a bus and on motorcycles, they were shooting in every direction, and I saw people fall to the street, killed and wounded… Four days later I returned to my neighborhood. When I got there… I walked into my house… I saw my father’s body burned in his bed and my nephew’s body burned on the ground.[77]

Some people tried to flee out to sea on boats, but members of criminal groups also shot at them, some witnesses said.[78] One of these small sailboats sank at night due to overcrowding and lack of visibility, according to the human rights organization Je Klere Foundation, which documented the case. Those on board included eight babies who died, witnesses told the group, and other adults remain missing.[79]

Pauline M., a 45-year-old mother of five, lost one of her children on April 19. “After I fled, I found out from a neighbor that one of my sons … tried to flee on a boat with some neighbors, but the boat sank,” she told Human Rights Watch.[80]

Isabel G., a 51-year-old mother of eight, said she was in her home in Source Matelas on April 19 with her 25-year-old son when they started hearing gunshots all around. Masked criminals forced their way into the house. One of them hit her in the face, and then two of them raped her, she said. Her son was shot in the foot while running away. He made it to the coast and boarded a small boat, but the boat capsized, and he and many others drowned.[81]

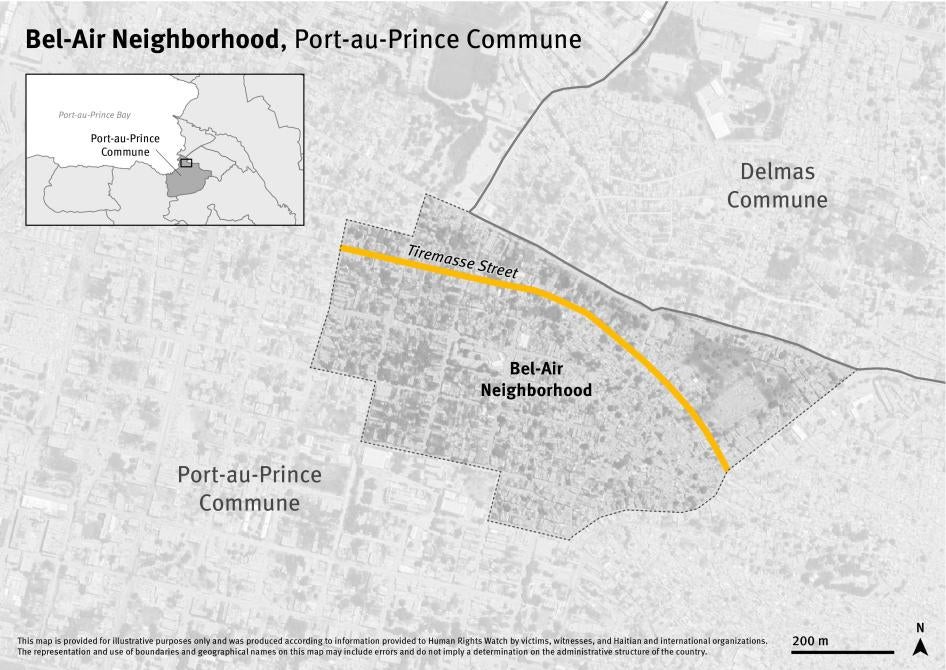

Attack in Bel-Air (Port-au-Prince)

On February 28, 2023, the Gang of Krache Dife led by Gady Jean (alias “Pèse”), a member of the G9 alliance that controls the lower sector of Bel-Air, attacked the upper sector of the neighborhood, which is controlled by the Kempès Sanon, a criminal group not affiliated with any of the large criminal coalitions.[82] The ensuing clashes lasted until March 5. At least 150 people were killed or reported missing, including some who may have been members of criminal groups, as well as local residents unaffiliated with the groups, and more than 80 houses were burned, looted, or vandalized, according to Haitian human rights organizations.[83]

The upper Bel-Air section—where almost 13,000 people live—separates the Delmas neighborhood, controlled by the G9 leader “Barbecue,” from the lower Bel-Air sector, also controlled by this coalition. G9 members need to traverse the upper Bel-Air sector, not under their control, in order to carry out criminal activities such as the transport of kidnapped people between areas that they do control.[84] The attack may thus have been either an attempt to expand control or to counter resistance.

One human rights group also alleged, based on victims’ and local residents’ testimonies, that the Krache Dife assailants received material support from Haiti’s national police, including three armored cars that were used in the attack.[85] Kempès Sanon also reportedly received material and personnel support from other criminal groups from Grand Ravine and Village de Dieu to repel the attack.[86]

Human Rights Watch presented these findings to the Haitian National Police and requested a response to the allegations in a letter dated on July 12 but had not received a reply as of August.

Human Rights Watch interviewed five victims and witnesses from this incident and documented 13 killings and three cases of sexual violence, the majority of which took place on Tiremasse Street, a key access road for the upper sector of the neighborhood. According to victims’ relatives, the attacks appeared to initially target those accused of collaborating with or being members of the rival group, and later targeted residents at random.[87]

Josie L., a 28-year-old woman who lives in Bel-Air with her 32-year-old partner, two children, and 64-year-old father, who has a disability, described how she was sexually assaulted by four members of the G9 alliance on February 28:

While I was leaving [home], I encountered four men who were armed, as if patrolling the street. They took me to an abandoned house nearby, and all four raped me. I was raped in the vagina and anus… It was very painful… All the time they threatened me, they told me that if I told other people what they did to me they would kill me or my family.[88]

That same day, after being sexually assaulted, Josie left her home with her partner, father, and children and went to an improvised camp for displaced people in Poste-Marchand. The next day, her partner returned to the neighborhood where a neighbor saw him being shot in the chest and set on fire by assailants on Tiremasse Street. A week later, Josie said she returned home to gather some of her belongings and found that her house had been burned down.

Valerie B., a 30-year-old mother of three, told Human Rights Watch:

My neighborhood, the upper section, is controlled by the gang under the command of Kempès. The members of the gang led by Ti Manno, which is part of the G9, attacked us… Initially the clashes were between them … but then the war was against us, the neighborhood residents. On March 3, I was on Tiremasse Street… when I heard a lot of gunshots… [I] ran towards my house and saw that my father, who had stayed at home, had been taken by two men… One of them shot him in the head and another began to cut off his arms with a machete, before dousing him in gasoline and burning him. My father was 44 and worked at a public cleaning company. He had nothing to do with the criminal groups.[89]

Valerie’s five-year-old son, who had stayed at home that day, was burned to death when the criminals set fire to the house. “When I managed to get into my house, he was wrapped in a blanket, totally charred,” she said.[90]

More killings and displacement cases were reported until late June in Bel-Air.[91]

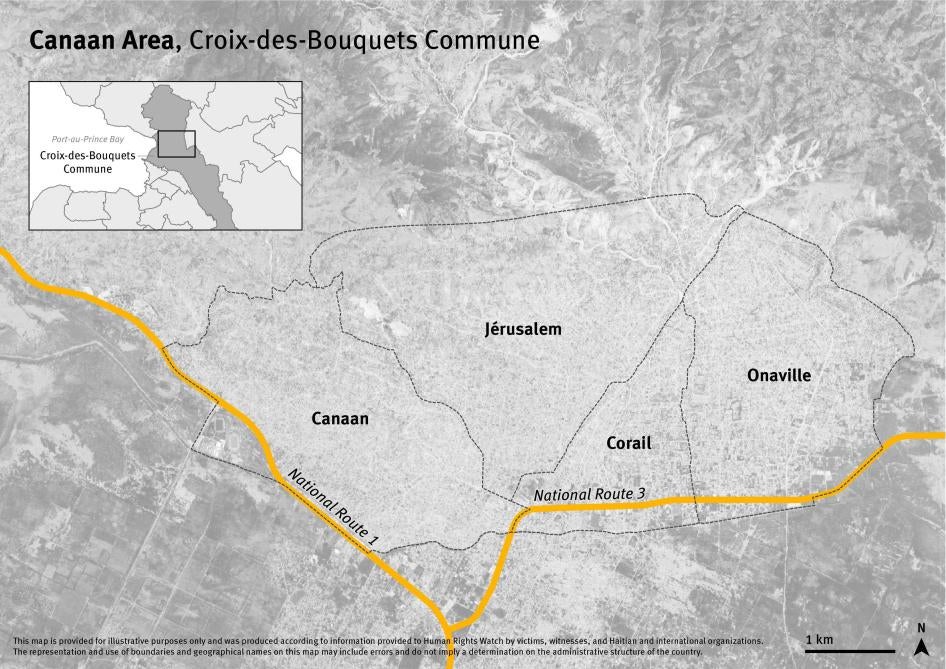

Expansion of Criminal Groups in Canaan (Croix-des-Bouquets)

From January 21 to late February 2023, the Gang of Canaan, led by “Jeff,” launched an offensive to expand its area of control in the Canaan area of Croix-des-Bouquets commune. The group previously controlled Saint Christophe and Canaan neighborhoods, and wanted to expand into three more neighborhoods: Corail, Jerusalem, and Onaville.[92]

Dozens of residents were killed during this offensive, according to a Haitian human rights organization that investigated the attack, and many were forced to flee their homes.[93] Human Rights Watch interviewed 11 victims and witnesses of this incident and documented 12 cases of killings. Many displaced families are being temporarily housed outside a church in Delmas commune, with the support of IOM.

Canaan was planned as an urban settlement built to house the survivors of the 2010 earthquake. The national roads that connect the capital to the departments in the north and east of the country pass through the area, making it strategic for criminal groups and their economic interests.[94] Gaining control of Corail, Jerusalem, and Onaville would allow the Gang of Canaan to control and profit from kidnapping and illegal taxation at checkpoints along parts of National Route 3, which has become a key transit road since other criminal groups wrested control of National Route 1 from the Gang of Canaan.[95]

Until this episode, Corail, Jerusalem, and Onaville were considered relatively safe neighborhoods of the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince. The violence illustrates how economic interests are driving criminal groups to expand to new areas.[96]

Angelique V., a 26-year-old saleswoman, described how she was attacked on January 21, 2023, when she was in the Corail market. “They [the criminals] started to shoot… at everything in the market, everyone,” she said. “Their leader is Jeff… and they want to control the entrance to the neighborhood, because they want control of the access routes to Port-au-Prince, and those routes pass through here.”[97]

As Angelique fled through the streets, she saw her neighbor, a 54-year-old carpenter, shot in the back, after which the assailants burned his body. A few days after, her brother-in-law told her that her 28-year-old husband, who had fled during the attack, had also been killed and his body burned.[98]

According to some witnesses, members of the criminal group were looking first for members of the police force and their families, and then attacked other residents with no connection to the police.[99]

Simón C., a 45-year-old resident of Corail, told Human Rights Watch:

On January 21… I was at home cooking with my children when I started to see several armed men arriving… We hid underneath the bed… The next morning, my kids and I left… While I fled, I saw that two houses that belonged to police officers living on that street had been set on fire, they were in flames… Jeff’s men arrived asking for police officers and the houses of their families, and they burned them.[100]

Members of Jeff’s group took over houses that had been abandoned by residents who fled, and some of those who tried to come back said they were told they would need to pay significant amounts of money to get their houses back.[101] “Many people warned me that my house was already occupied by criminals and that I couldn’t go back inside,” a 51-year-old resident of Corail said. “I asked a neighbor to ask [the criminals] if I could go back… They told me that I could if I paid … [US] $500.”[102]

More killings and displacement cases were reported until late June in Canaan.[103]

II. Catastrophic Humanitarian Situation

I was born in Cité Soleil… I’ve lived there my whole life... The situation is worse now than it has ever been. We have nothing to eat, no water, and our house is burned. Life is really difficult.

— A 29-year-old resident of Brooklyn[104]

The security crisis is compounding a humanitarian situation that has been critical for years. Access to food, electricity, safe drinking water, sanitation, health care, and education in Haiti is severely limited.[105] Nearly 59 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, with limited access to basic services.[106] Humanitarian agencies estimate that 5.2 million Haitians, 57 percent of them girls and women, now need humanitarian assistance, an increase of 20 percent compared to 2022.[107]

Nearly half of Haiti’s population, or 4.9 million people, are acutely food insecure, and of these, 1.8 million are facing emergency levels of food insecurity. In September 2022, over 19,000 people living in Cité Soleil commune faced catastrophic hunger for the first time on record in Haiti and in the Western hemisphere. Haiti is now one of the countries with communities most at risk for starvation, alongside Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Mali, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Yemen.[108] The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) elevated Haiti to “the highest concern level” for food insecurity during the outlook period from June to November 2023.[109]

Only 47 percent of Haitians had access to electricity as of 2020, according to the World Bank.[110] Other sources estimate lower figures, saying that as of early 2023, only a third of the Haitian population had access to electricity—and only intermittently and at high prices—further hindering access to goods and services, food preservation, and business operations.[111]

Only 55 percent of Haitian households have access to basic drinking water, and two-thirds of the population has limited or no sanitation services, aggravating the nationwide spread of cholera.[112] Since the current outbreak started in October 2022, Haiti’s Health Ministry reported 56,580 suspected cases of cholera (almost half in children under the age of 14), 3,612 confirmed cases, and 814 deaths across the country’s ten departments as of July 26, 2023.[113]

International organizations estimate that 75 percent of the country’s health facilities have inadequate supplies of medicine or medical equipment and lack sufficient trained personnel. In recent years there has been a massive exodus of health workers from Haiti due to insecurity, which has further hindered the population’s access to health services.[114]

“The national health system is on the verge of collapse” and “cannot respond to the country’s malnutrition crisis and ongoing cholera outbreak,” reported Catherine Russell, Executive Director of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), on June 16, 2023.[115]

According to UNICEF, 4.2 million children have been deprived of their right to education due to high education costs, insecurity at school or on the way to school, or lack of infrastructure and staff.[116] The Haitian Ministry of Education reported in early May that fewer than 645,000 students attend Haiti’s 18,950 registered schools.[117]

Education in Haiti has been severely disrupted for four years and children are estimated to have lost a full school year over this period due to political demonstrations and unrest, as well as the Covid-19 pandemic, natural disasters, and increased insecurity that has caused the destruction of some schools and temporary or permanent closure of others.[118]

Humanitarian Conditions in Areas Controlled by Criminal Groups

Populations living in areas controlled by criminal groups suffer from a particularly extreme lack of access to basic services and food, as violence and insecurity prevents them from obtaining goods or accessing services for days, weeks, and even months at a time. In Cité Soleil, for example, in 2022, at least 19,200 people faced the risk of starvation according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 20 percent of children under five suffered from acute malnutrition, and 80 percent of households did not have access to drinking water.[119]

Some healthcare centers run by international organizations in the area, which were barely able to meet needs before the present crisis, have closed because of the insecurity.[120] On March 9, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, Doctors without Borders) temporarily closed its Cité Soleil hospital, resuming only emergency care activities at the end of March.[121] Many schools have closed, and some criminal groups have used schools as bases, damaging and looting them in the process.[122]

Since mid-2021, Brooklyn residents have lacked access to electricity after G9 members reportedly cut the cable that provided the service.[123] They also did not have any access to safe drinking water between mid-March 2023 and late April, when the G9 prevented water delivery tanker trucks from entering the area.[124] Although they were recently allowed to enter Brooklyn, the trucks were reportedly blocked during some weeks from entering because the access roads were inundated with mud.[125] The city’s sewage canals that run through this area to the sea have not been maintained, meaning that the limited access routes and many homes are regularly flooded with mud and garbage, contributing to new cases of cholera.[126]

Anne J., a Brooklyn resident, told Human Rights Watch about the challenges her family faces:

We don’t eat every day, sometimes yes, sometimes no... We don’t have drinking water, we only drink rainwater, my children are sick to their stomachs … We haven’t had electricity for a long time either. It’s the G9 gang that cut the cables … For several weeks our house has been flooded; every time it rains, it floods and smells bad because the garbage goes down the canals. We live on top of mud and garbage.[127]

Violence also disrupted supplies to the neighborhood market and access to surrounding markets, forcing residents to leave the commune to obtain food and other goods.[128]

“When we’re wounded, there’s no hospital. There’s no water. No food. The water trucks haven’t been able to enter since the war started in early March. People are hungry, and they can’t get food,” Natalie P., another Brooklyn resident, told Human Rights Watch.[129]

Julieth F., another resident, said: “The schools are closed, we don’t have water or electricity, we don’t have food. We live on top of the dirty water that comes down the mountain through the canals, and in the middle of the garbage … My children look in the garbage to try to recover things that can be used for the house, or so we can eat.”[130]

No humanitarian aid entered the Brooklyn area during clashes occurring between mid-March and late April 2023.[131] Some humanitarian and human rights organizations have recently managed to provide Brooklyn residents with assistance before and after the clashes. Residents said that they had received no support from the state.[132]