Summary

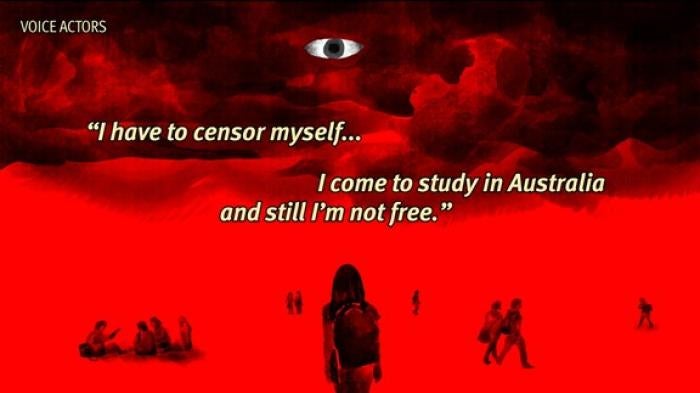

I have to censor myself. This is the reality. I come to Australia and still I’m not free.

—Lei Chen (pseudonym), student from mainland China describing his experience studying in an Australian university, September 25, 2020

You have to choose your words very carefully. I look at my university and see the place is absolutely hooked on Chinese foreign student money.

—Academic “T” (pseudonym), November 12, 2020

In 2020, nearly 160,000 students from China were enrolled in Australian universities. Despite the Chinese government in Beijing being thousands of kilometers away, many Chinese pro-democracy students in Australia say they alter their behavior and self-censor to avoid threats and harassment from fellow classmates and being “reported on” by them to authorities back home.

Students and academics from or working on China told Human Rights Watch that this atmosphere of fear has worsened in recent years, with free speech and academic freedom increasingly under threat. The Chinese government has grown bolder in trying to shape global perceptions of the country on foreign university campuses, influence academic discussions, monitor students from China, censor scholarly inquiry, or otherwise interfere with academic freedom.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, approximately 40 percent of all onshore international students in Australia came from China, with Chinese students making up roughly 10 percent of all students attending Australian universities. Even with borders closed due to the pandemic, international education remains one of Australia’s top exports as universities put courses online and some international students remain in the country.

This research builds on Human Rights Watch’s 2019 research into the Chinese government’s efforts to undermine academic freedom globally, which included a 12-point Code of Conduct for colleges and universities to adopt to respond to Chinese government threats to the academic freedom of students, scholars, and educational institutions.

Surveillance, Harassment, and Threats

The Chinese government maintains surveillance of Chinese mainland and Hong Kong students in Australian universities. Human Rights Watch verified three cases of students whose family in China were visited or were requested to meet with police regarding the student’s activities in Australia. While this number is low (though other cases may not have been reported to Human Rights Watch), the fact this occurs at all is enough to keep thousands of other students on edge and fearful.

Current threats to and limitations on academic freedom at Australian universities stem from China-related pressures and documented cases of harassment, intimidation, and censorship of students and academics from China, and faculty members who criticize the government or express support for democracy movements. These corrosive dynamics set in motion considerable self-censorship.

Students said the fear of fellow students reporting on them to the Chinese consulate or embassy and the potential impact on loved ones in China led to stress, anxiety, and affected their daily activities. Fear that what they did in Australia could result in Chinese authorities punishing or interrogating their parents back home weighed heavily on the minds of every pro-democracy student interviewed. It was a constant concern that had to be evaluated before decisions were made of what to say, what they could attend, and even with whom they were friends.

Pro-democracy students from mainland China and Hong Kong experience direct harassment and intimidation from Chinese classmates—including threats of physical violence, being reported on to Chinese authorities back home, being doxed online, or threatened with doxing. These acts occurred in various environments, including online, in-person, and on and off campus.

Students were targeted for harassment and intimidation after being identified by their classmates as criticizing the Chinese Communist Party, expressing support for democracy in China or Hong Kong, or if they attended a protest in support of Hong Kong democracy.

This abusive behavior of intimidating or “reporting on” classmates does not represent most Chinese students in Australia, the majority of whom do not get involved in political disputes or choose to express their views peacefully. Instead, it is carried out by a small but highly motivated and vocal minority who have the potential to influence many others.

Many students expressed disappointment and dismay that Australian universities were not doing enough to protect them and their academic freedom. Most pro-democracy students interviewed who experienced harassment and intimidation said they did not report it to their university. Those who did not report these incidents believed that their university would not take the threat seriously, believing their university was sympathetic to nationalistic Chinese students or gave priority to maintaining their relationship with the Chinese government.

Students and social media users supportive of the Chinese government have subjected academics to harassment, intimidation, and doxing if the academics are perceived to be critical of the Chinese Communist Party or discuss “sensitive” issues such as Taiwan, Tibet, Hong Kong, or Xinjiang. Such incidents have taken place numerous times over the last few years on Australian campuses, and they continue to occur.

Interviewees attributed the recent increase in harassment and intimidation of students and academics to the deteriorating human rights situation in Hong Kong, and Australian-based students’ involvement in demonstrations and expressions of solidarity with those back home. The growing number of incidents should also be seen in the context of efforts by the Chinese government and the Party to influence and “call on” Chinese students studying abroad, with Chinese President Xi Jinping designating them as a “new focus” of United Front Work in 2015. Nearly all academics interviewed pointed to a marked increase in the level of nationalism among their students from China since President Xi came to power in 2013.

Culture of Self-Censorship

Both students from China and academics who work on China have adopted self-censorship as the most common strategy to avoid threats, harassment, and surveillance. As a result, frequent self-censorship on issues relating to China now threatens academic freedom in Australia. A significant majority of pro-democracy Chinese and Hong Kong students interviewed said they self-censored while studying in Australia.

More than half of faculty interviewed, selected because they are from or specialize in China studies, or teach a large number of PRC students, said they practiced regular self-censorship while talking about China. University administrators censoring staff also occurred but was much less frequent, with examples of administrators asking staff not to discuss China publicly, or discouraging them from holding public China-related events or speaking to the media about sensitive China issues.

Self-censorship is common by academic staff who do not feel protected enough to discuss controversial topics around China because they feel that universities do not “have their back.” For nearly all academics interviewed, how to discuss China in the classroom had become a major issue in their professional lives.

Rising self-censorship is also related to fears of nationalistic Chinese students recording and reporting on class discussions, the now-regular university practice of recording and uploading most lectures and tutorials, and concerns of doxing online.

Fears of visas to China being rejected, for Chinese colleagues, or for family still in China also drove academics to self-censor. Nearly all academics highlighted their university’s failure to recognize this culture of self-censorship or develop any official policy to address it and support staff, even in circumstances when staff raised it with their supervisors.

Failure to Recognize Risks to Students and Staff

Teaching online during the Covid-19 pandemic has also posed new challenges for academics who suddenly had to teach units to students who had returned to mainland China. Course material designed for Australian campuses was now being accessed by students behind the “Great Firewall” of China, which posed new and difficult security risks for students and academics alike. Despite this, many academics said their university had not offered any official guidance on teaching Chinese students remotely and the security considerations.

Australian universities have also not grasped the full consequences of the extraterritorial reach of Hong Kong’s new National Security Law and the potential impact it could have students studying in Australia. The law, which China’s government imposed in June 2020, is Beijing’s most aggressive assault on Hong Kong people’s freedoms since the transfer of sovereignty in 1997. Its provisions include creating specialized secret security agencies, the denial of fair trial rights, sweeping new powers to police, increased restraints on civil society and media, and the weakening of judicial oversight.

Students and academics consistently raised concerns that Chinese students studying in Australia are able to live in an information vacuum akin to life in China. This is largely due to an overreliance on the heavily censored Chinese social media platform WeChat, which is the dominant social platform in China and often the only way to communicate with loved ones back home. The misinformation and lack of diverse views that exist in this Communist Party-controlled environment are viewed as a potential motivating factor behind the harassment and intimidation by some students of those who want to speak out or express different opinions. Embassy and consulate-linked student bodies dominate the support networks for students from China, and this poses difficulties for those who do not want to have any association with the Chinese state.

Focus on National Security, Rise in Racism

In 2017, Australia’s intelligence agency, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), warned of an increase in China's alleged attempts to interfere in domestic affairs, sparking a national debate around “foreign interference” and concerns around national security implications for Australia. Since then, political and media commentary has focused on many alleged examples of interference. As part of that, some media outlets have portrayed Chinese students as unthinking, untrustworthy, manipulable defenders of the Chinese Communist Party.

This depiction—simplistic, unfair, and at times racist—fails to consider the many challenges these young people face when suddenly living in a multicultural democracy after growing up in a strictly controlled state. Many of these students have only ever been exposed to an academic system in which diverse views are not encouraged. The institutions hosting them do little to protect their academic freedom, leaving them vulnerable to pressure from other students and from Chinese authorities.

Racism and discrimination faced by Asians in Australia has increased dramatically in the past year. A March 2021 report by the Lowy Institute in Sydney found that almost one in five Chinese Australians say they have been physically threatened or attacked in the past year, with most blaming tensions stemming from the Covid-19 pandemic or hostility between Canberra and Beijing. Around one in three community members reported they have faced verbal abuse or discriminatory treatment.

University officials are acutely aware of the financial impact full fee-paying international students have on their institutions and how reliant they have become on their fees, which accounted for 27 percent of total operating revenue for the Australian university sector by 2019. Australian universities are in a difficult position: while the government once encouraged engagement with China, Canberra now views relationships with Chinese state institutions with suspicion. Border restrictions imposed due to the Covid-19 pandemic are forcing the Australian higher education sector to examine its over-reliance on full fee-paying international students.

A plethora of reviews, taskforces, and inquiries in the past few years that have examined issues of foreign inference at Australian universities have not made concrete recommendations to protect the safety and well-being of students and staff. There is a lack of oversight and accountability mechanisms to ensure their academic freedom and security.

In Australia, university administrators of eminent institutions have repeatedly expressed to Human Rights Watch that they have robust policies to protect free speech and academic freedom. They point to their current student and staff codes of conduct as well as existing student complaint and support systems to assert their institutions are well placed to manage these threats. Universities have highlighted a commitment to implement the new government-commissioned Model Code on Free Speech or steps taken to already implement the code when we asked about these issues. But despite these services, policies, and commitments, the threats to free speech and academic freedom continue.

These issues have been difficult to identify, partly because most students and staff do not report these incidents. As a result, Australian universities have not been aware of the extent of the problem, leaving academic freedom eroded by self-censorship rather than outright repression. This also makes it easier for Chinese authorities to escape scrutiny over their actions. In the meantime, students, faculty, and genuine academic freedom of instruction and inquiry all suffer.

Positive Steps

Public hearings in March 2021 as part of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security’s inquiry into national security risks affecting the Australian higher education and research sector indicated a greater willingness by universities towards confronting Chinese government interference.

Testimony by vice-chancellors from several of Australia's largest universities signify that they are now taking these issues seriously and are keen to work with the government’s recently established University Foreign Interference Taskforce (UFIT) to develop new systems and safeguards for their institutions and how to adopt the taskforce’s guidelines for dealing with foreign interference.

However, despite making these commitments, discussion remains focused on protecting university research interests and national security while the universities remain unprepared to address threats to academic freedom in a systematic way for students from China and China-focused academics, or responding to issues of censorship and self-censorship.

Australian government departments, universities, and the higher education sector should adopt concrete procedures for dealing with threats, intimidation, self-censorship, and censorship affecting students from China and Hong Kong and China-focused academics.

Universities will be best served if they commit to acting together to confront China’s threats to academic freedom. Alongside sector representatives like Universities Australia and The Group of Eight, universities should, where beneficial, work collaboratively on these issues. By doing so, they will reduce the risk of being individually targeted by the Chinese government for retribution for daring to speak out.

Glossary

|

ASIO |

Australian Security Intelligence Organisation |

|

CSSA |

Chinese Students and Scholars Association, the main student body in Australia for Chinese students, which has formal links with the Chinese embassy and consulates, including funding support and organizing pro-Communist Party political gatherings |

|

CCP |

Chinese Communist Party |

|

Doxing |

Publishing personally identifiable information about an individual without their consent, sometimes with intent to provide access to them offline, exposing them to harassment, abuse, and possibly danger |

|

Hong Konger |

A person from Hong Kong |

|

Lennon Wall |

Artistic expressions of support created by Hong Kong pro-democracy demonstrators that feature sticky notes covered in protest slogans and messages of support, forming large colorful pop-up mosaics |

|

PRC student |

A student from mainland People’s Republic of Chin |

|

The Group of Eight |

An alliance of Australia’s leading research-intensive universities. It includes the Australian National University, Monash University, the University of Adelaide, the University of Melbourne, the University of New South Wales, the University of Sydney, the University of Queensland, the University of Western Australia |

|

Universities Australia |

An industry representative body for universities in Australia that attempts to advance higher education through voluntary, cooperative, and coordinated action |

|

|

A Chinese-language multi-purpose messaging, social media, and mobile payment app developed by the Chinese company Tencent. It became the world's largest standalone mobile app in 2018 and currently has more than 1 billion monthly active users |

Key Recommendations

To the Australian Government

- Publish annually a report documenting incidents of harassment, intimidation, and censorship affecting international students that occur at Australian universities and steps taken by those universities to counter those threats.

- Establish a mechanism so students at Australian universities can report harassment, intimidation, pressures of censorship or self-censorship, and acts of retaliation involving foreign governments.

To the University Foreign Interference Taskforce

- Examine as a priority the harassment, intimidation, censorship, and self-censorship of students and academics from China and working on China.

To Australian Universities and Vice-Chancellors

- Speak out publicly when specific incidents of harassment or censorship occur. Commit to consistently supporting academic freedom and freedom of expression through public statements at the highest institutional levels.

- Define “reporting on” the activities of fellow students or staff to foreign embassies as bullying and harassment, classifying it as a serious violation of the student code of conduct and grounds for disciplinary action.

- Ensure Chinese students, academics, and staff feel welcomed and protected and that anyone who engages in harassment or discrimination is appropriately punished.

A full set of recommendations is found at the end of the report.

Methodology

In recent years, the Chinese government has grown bolder in trying to shape global perceptions of China on university campuses and in academic institutions outside China, influence academic discussions, monitor overseas students from China, censor scholarly inquiry, and otherwise interfere with academic freedom.

This research builds on Human Rights Watch’s 2019 research into the Chinese government’s efforts to undermine academic freedom globally, which included a 12-point Code of Conduct for colleges and universities to adopt to respond to Chinese government threats to the academic freedom of students, scholars, and educational institutions.[1]

This report is based on 48 interviews conducted between September 2020 and April 2021.

The interviewees include 24 “pro-democracy” international students studying at Australian universities—11 from mainland China and 13 from Hong Kong. Two students who belonged to the Chinese Students and Scholars Association were also interviewed. Many other students were contacted but ultimately declined to be interviewed due to security fears.

Twenty-two academics who teach Chinese or Hong Kong students or their key area of expertise is China, were also interviewed.

While these 24 pro-democracy students make up a miniscule proportion of the student community in Australia, their experiences speak to the challenges faced by hundreds and possibly thousands of students from China studying in Australia who want the freedom to express their opinions.

The assessments of the 22 academics interviewed, and their experiences and observations of similar themes and patterns raised by the students, supports the finding that these issues are occurring across university campuses throughout Australia.

Students and academics were interviewed who attended or taught at the following universities: the Australian National University (ANU), Curtin University, Edith Cowan University, La Trobe University, Macquarie University, Monash University, RMIT University, the University of Adelaide, the University of Melbourne (UOM), the University of New South Wales (UNSW), the University of South Australia, the University of Sydney, the University of Tasmania, the University of Technology Sydney (UTS), the University of Western Australia (UWA), the University of Queensland (UQ), and the Queensland University of Technology (QUT).

Human Rights Watch wrote to each of these universities with a list of questions. All replied except for the Australian National University and the University of Adelaide. Replies can be found in full on Human Rights Watch’s website.

Due to Covid-19 travel and social distancing restrictions, interviews were conducted by phone, voice and text message, and email. Human Rights Watch informed interviewees of the purpose of the interview and the way the information would be used. No remuneration or incentives were promised or provided to those interviewed. Security concerns meant interviews were conducted via encrypted apps and secure networks and servers.

Names of all interviewees for this research have been withheld to protect their identity. All names used are pseudonyms. The highly sensitive nature of the topics discussed and the fears Chinese citizens expressed that they or they families could face repercussions for speaking to Human Rights Watch made this necessary.

Quoted academics are anonymous due to concerns that speaking publicly on China-related topics could result in repercussions from their universities.

Citations for Human Rights Watch interviews contain minimal information to avoid identification of the person.

I. Background

Australian University Dependence on International Students

In the past 20 years, international students have become a valuable part of Australian university campus life and a critical revenue stream for Australian universities. The total number of international higher education students at Australian institutions has nearly doubled since 2008 and more than tripled since 2002, with most growth occurring onshore.[2]

By 2017, 430,000 foreign students were enrolled in Australian higher education institutions, accounting for roughly 28 percent of all students.[3] International students earned education institutions in Australia more than AU$17 billion (US$13.6 billion) in tuition fees in 2019.[4] As a result, Australian universities have become increasingly dependent on income from these lucrative fees, which accounted for 27 percent of total operating revenue for the Australian university sector by 2019.[5] This increasing reliance was reinforced when federal government funding for higher education was reduced by AU$2 billion (US$1.5 billion) in real terms in 2017.[6]

In particular, students from China sought Australia as a study destination as the Chinese middle class grew alongside Australia’s reputation for quality higher education and post-study migration and employment opportunities.[7] Approximately 40 percent of all onshore international students in Australia came from China in 2018, with Chinese students making up approximately 10 percent of all students attending Australian universities.[8]

In a 2019 report entitled “The China Student Boom and the Risks It Poses to Australian Universities,” sociologist Salvatore Babones identified seven Australian universities as having “extraordinary levels of exposure to the Chinese market.”[9] These were the University of Melbourne, the Australian National University, the University of Sydney, the University of New South Wales, the University of Technology Sydney, the University of Adelaide, and the University of Queensland.

Babones noted that the University of Sydney was the most exposed, generating more than a half-billion Australian dollars (US$387 million) in 2017 from Chinese student course fees, which accounted for approximately 23 percent of its total revenues of over AU$2 billion (US$1.5 billion).[10] The next in line was the University of New South Wales, with 22 percent of its revenues from Chinese students. The University of Technology Sydney was third with 19 percent.[11]

The report found that this number of Chinese international students was unique to Australia, with approximately 10 percent of all students in Australia coming from China, compared to 6 percent in the United Kingdom, 3 percent in Canada, and 2 percent in the United States.[12]

This dependency on international students was exposed during the Covid-19 pandemic as Australian border closures saw many international students stuck overseas, unable to enter the country and take up their studies. In 2020, Australian universities shed 17,000 jobs and lost an estimated AU$1.8 billion (US$1.39 billion) in revenue, blamed on the pandemic and a sharp drop in international enrollments.[13] The Australian government’s decision to exclude universities from “JobKeeper” payments, a wage subsidy scheme designed to support businesses financially during the pandemic, has also contributed to new financial crisis in the higher education sector.[14]

Yet, even with the Covid-19 pandemic, education remains one of Australia’s key exports, as universities put courses online and some international students remained in the country. By December 2020, approximately 160,000 Chinese students were enrolled to study in Australian universities, with about half studying remotely in China and the others continuing to learn in Australia.[15] Universities are currently exploring options to expedite the return of international students to Australia, attempting to find methods to overcome the country’s strict border controls in response to Covid-19.[16]

China-Related Incidents and Academic Freedom 2013–2018

For the past decade, as Australian universities have become increasingly reliant on income from Chinese international students, there has been a growing number of reported incidents of restrictions on academic freedom, intimidation, and censorship on matters related to China.

In the 1980s and 1990s, holding events or protests on subjects such as Tibet, Taiwan, and the Tiananmen Square massacre would not be controversial on university campuses. But by 2013, Chinese consulates had become proactive in complaining to universities about certain events and speakers and universities started to back away from discussions on topics considered sensitive in China.

In 2013, for example, Sydney University made headlines when a talk by the Dalai Lama, the spiritual and political leader of Tibet, was moved off campus. The university warned organizers not to use its logo or to allow media coverage or Tibet activists entry into the event.[17] In an email obtained by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), Sydney University’s Vice-Chancellor Michael Spence expressed relief at the outcome, praising it as “in the best interests of researchers across the university.”[18] Several years later, in June 2017, a University of Sydney professor described how “someone from the [Chinese] consulate visited the university and urged the university” to rethink staging a planned forum on the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. The professor said, “These things are not unusual” and despite the approach, “the university stood by us” and the event proceeded.[19]

In April 2018, the University of Western Australia (UWA) student guild retrospectively passed a motion to express concerns about a visit by the Dalai Lama on campus three years earlier. The motion urged UWA to liaise with the guild to ensure guests do not “unnecessarily offend or upset groups within the student community” and to consider the “cultural sensitivities of all groups.[20] It also said the student guild “recognises the negative impact that hosting the Dalai Lama at the University has on the UWA Chinese Student Community.”[21] UWA’s student newspaper reported that no formal evidence was produced to the guild regarding why the motion was necessary, but that advocates for the motion “mentioned that they had been in contact and engaged in consultation with many Chinese students on campus who felt strongly about the issue.”[22]

Academics have also faced blowback from some pro-Chinese government students for comments or criticism deemed to be insensitive or critical of China. At the University of Newcastle in New South Wales in August 2017, a Chinese student secretly recorded an exchange with their lecturer, who described Taiwan as a country—which the student complained was offensive. The footage was leaked to and published by Sydney Today, a pro-Chinese government Chinese language website.[23] The same month, Chinese students at the University of Sydney criticized their lecturer on WeChat and called on students to quit his class, after an IT academic displayed a map showing Chinese-claimed territory as part of India. The lecturer later apologized, saying he had inadvertently used an outdated internet map.[24]

Media also reported on several incidents of students from China facing harassment or intimidation, including of relatives back in China, for peaceful activities in Australia. A student at the Queensland University of Technology, Tony Chang, planned to participate in a protest in Brisbane in June 2015, the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre. He told the ABC that Chinese intelligence agents visited his family in China, who warned them to rein in their son’s activities in Australia. Chang spoke to the ABC about his belief that he and his family were being monitored and tracked.[25]

Chinese consulates have not been alone in registering complaints with Australian universities. The Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA), which has formal links to the Chinese embassy in Canberra and with state consulates, has also became more active as the numbers of Chinese students in Australia have grown.

In September 2016, the Australian Financial Review reported that the head of the CSSA allegedly shouted at staff in the Australian National University campus pharmacy, demanding they remove a stand holding the Epoch Times—the newspaper of the banned religious group Falun Gong, which publishes articles critical of the CCP—and threatening to organize a boycott.[26]

In August 2018, Chinese students at the University of Adelaide threatened to report fellow Chinese classmates to the embassy for campaigning against Communism during student elections, The Australian newspaper reported, with intimidating messages allegedly circulated on the Chinese media platform WeChat.[27]

United Front and Chinese Government Targeting of Chinese Students Studying Overseas

The growing number of incidents at Australian universities have occurred in the context of CCP efforts to influence people from China living outside the country and use them to promote the Party’s causes and positions. Part of this is to “call on” Chinese students studying abroad.

Within the CCP, a special section called the United Front Work Department (UFWD) is responsible for organizing outreach to key Chinese interest groups, including ethnic Chinese abroad, and representing and influencing them. Since Xi Jinping became Communist Party general secretary in 2012, he has overseen a dramatic expansion of the UFWD’s role and who it targets.[28]

“In its simplest terms, the UFWD is about uniting those who can help the party achieve its goals and neutralize its critics,” University of Adelaide Sinologist Dr. Gerry Groot said. “Its work is often summed up as ‘making friends,’ which sounds benign, and often is. But it can have other meanings, such as helping to stifle dissent at home and abroad.” [29]

Overseas Chinese students have long been a target of the United Front, but in 2015, this was reinforced when Xi Jinping designated them as a “new focus of United Front work.”[30]

“These efforts seek to maintain the CCP’s influence over Chinese students even when they are overseas and ensure that some can be mobilized when needed,” said analyst Alex Joske at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.[31] This new focus by the CCP appears designed to ensure these students “always follow the Party” and do not return to China with a newfound opposition to Communist Party rule, after potentially being exposed to commentary critical of the Party while abroad.[32]

A new directive was sent to education officials in February 2016:

Assemble the broad numbers of students abroad as a positive patriotic energy. Build a multidimensional contact network linking home and abroad—the motherland, embassies and consulates, overseas student groups, and the broad number of students abroad—so that they fully feel that the motherland cares.[33]

A new CCP online cyber policing portal that encourages Chinese internet users to report acts that undermine Beijing's image was exposed by the Sydney Morning Herald in August 2020. The online portal allows internet users to lodge “reports” for any perceived “attacks” on the Party and state systems, the position of President Xi, undermining territorial integrity and endangering national security, reported the newspaper, pointing out that the site was accessible in Australia.[34]

Australia’s Foreign Interference Laws

In the wake of increased reporting in 2017 of incidents by the media regarding alleged influence by the Chinese Communist Party, high-ranking Australian intelligence and government officials began publicly warning Australian universities to be vigilant about foreign interference and stifling debate on campuses.

In October 2017, Australia’s most senior diplomat, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Secretary Frances Adamson, warned international students to resist the Chinese Communist Party's “untoward influence” and called on universities to “remain true” to their values and be “secure and resilient” against foreign interference.[35]

Later that month, the head of Australia's domestic intelligence agency, ASIO, Duncan Lewis, said that the government needed to be “very conscious” of foreign interference in universities. “That can go to a range of issues,” Lewis told a Senate estimates committee in Canberra. “It can go to the behavior of foreign students, it can go to the behavior of foreign consular staff in relation to university lecturers, it can go to atmospherics in universities.”[36] Lewis said that providing any more information publicly would compromise his agency's work.

In December 2017, then-Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull proposed a wide-ranging crackdown on foreign interference, with proposed new laws that would target “covert, coercive” activities. This was largely in response to allegations of Chinese government interference in Australian domestic politics. Turnbull noted recent “disturbing reports” of Chinese influence but stressed the laws would not target any one country.[37]

Both of Australia’s major political parties supported the new foreign interference laws, which parliament passed in June 2018. They added 38 new offenses, including interference with Australian democratic or political rights by conduct involving use of force, violence, or intimidation; stealing trade secrets on behalf of a foreign government; broadening the definitions of existing crimes like espionage; and making it illegal to engage in covert activity on behalf of a foreign government that aims to influence Australian politics.[38] Punishment for such crimes range from 10 to 20 years in prison.

Parliament also passed the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Act 2018, which places new requirements on persons and entities who have arrangements with, and undertake certain activities on behalf of, foreign principals seeking to exercise influence over Australian political and governmental decision-making and processes.[39] The new law means that individuals and entities, including universities, must register the nature of the activities undertaken on behalf of foreign principals and the purpose for which the activities are undertaken. This includes arrangements such as Chinese government-funded language centers known as Confucius Institutes and US government-funded study centers.

Free Speech Reviews

In November 2018, Australia’s Education Minister Dan Tehan announced an inquiry into free speech on university campuses to be carried out by former High Court chief justice Robert French.[40] This was a government response to the alleged influence of “left-wing activists” on campus after protesters targeted a Sydney University event featuring an author who dismissed claims of a “rape crisis” on campuses as a “feminist myth.”[41] In April 2019, French delivered the findings, reporting that there was no evidence of a systemic free speech crisis on Australian campuses.[42] The French review only briefly mentioned issues around free speech for Chinese students and academics working on China.[43]

French concluded that “claims of a freedom of speech crisis on Australian campuses are not substantiated” but recommended a national code to strengthen protections around free academic expression in response to growing fears.[44] The code spells out protections from disadvantage, discrimination, threats, intimidation, and humiliation but states there is no duty to protect staff and students from “feeling offended or shocked or insulted by the lawful speech of another.” All Australian universities agreed to implement the French code by the end of 2020.[45]

In the wake of new allegations involving Australian academics involved with a Chinese government academic recruitment program called the “Thousand Talents” program and several other reported free speech issues at universities, Education Minister Tehan announced yet another review in August 2020—this time to evaluate the progress Australian universities had made implementing the French Model Code on university free speech.[46]

Former Deakin University Vice-Chancellor Professor Sally Walker was recruited to carry out the review.[47] In December 2020, Walker concluded that while 33 universities had completed work to implement the French Model Code on free speech, only nine of Australia’s 42 universities had adopted policies that completely aligned with the French Model Code on free speech, despite the sector committing to having policies in place by the year's end.[48]

In February 2021, it was reported that Walker would provide each Australian university with a “free speech report card” and would work personally with each university to advise them on implementation of the code.[49]

Despite these efforts, even if all universities diligently adopt the French Model Code, it has significant gaps and is insufficient to deal with many issues regarding China’s threats to academic freedom in Australia.

As is, the French Model Code largely deals with protection of free expression in democracies and was drafted with students and academics from democratic countries in mind. It does not deal with the situation of students and academics from (or working on) authoritarian countries like China, and for whom academic freedom is curtailed in slightly different ways. The Model Code assumes all members of a given academic community are aware of, comfortable with, and confident in university bodies reporting Chinese government-related threats to academic freedom, and that universities will respond to those reports with informed and appropriate considerations.

Academic Code of Conduct

In March 2019, Human Rights Watch published a 12-point Code of Conduct for colleges and universities to adopt to respond to Chinese government threats to the academic freedom of students, scholars, and educational institutions.[50] The code derived from research tracking how Chinese government authorities have grown bolder in trying to shape global perceptions of China on university campuses and in academic institutions outside China.

The code was based on more than 100 interviews between 2015 and 2018 in Australia, Canada, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States with academics, graduate and undergraduate students, and administrators, some of them from China.

Human Rights Watch found that many colleges and universities around the world with ties to the Chinese government, or with large student populations from China, are unprepared to address threats to academic freedom in a systematic way. Few have moved to protect academic freedom against longstanding problems, such as the Chinese government’s visa bans on academics working on China, or surveillance and self-censorship on their campuses.

Efforts to Counter Foreign Interference

In August 2019, the Australian government announced a new University Foreign Interference Taskforce including representatives from universities, national security organizations and the Department of Education.[51] The taskforce consists of four working groups: to prevent and respond to cyber security incidents; to protect intellectual property and research; to ensure collaboration with foreign entities is transparent and does not harm Australian interests; and to foster “a positive security culture.”

The taskforce has developed guidelines for universities to address foreign interference, and while their overarching principle is to safeguard academic freedom, they place more emphasis on assessing research partnership and cyber security risk than harassment, intimidation, or self-censorship and the safety and security of students and staff.

In August 2020, reporting by The Australian newspaper highlighted the involvement of more than 30 Australian academics in the Chinese Communist Party’s “Thousand Talents” program.[52] The US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has identified the Chinese government initiative, which uses financial scholarships to recruit top scientific talent for research projects, as a potential means of economic espionage.[53] Australia’s domestic intelligence agency ASIO has been briefing universities on the national security risk of such programs.[54]

In December 2020, Australia’s parliament passed new legislation giving the federal government power to veto any agreement struck with foreign states.[55] Universities Australia, the key peak lobby group for Australian universities, expressed concern with the new law, which would mean any university agreement with state-backed Chinese institutions will now come under closer scrutiny.

A parliamentary inquiry into foreign interference threats in Australia’s universities was also announced in November 2020, focusing mainly on potential security risks affecting the higher education and research sector.[56]

II. Harassment, Intimidation, and Surveillance

At around 2 a.m. I received a message from a mainland classmate.

He was like, “I’m watching you.”

—Zhang Xiuying, PRC student at an Australian university, November 2020[57]

Of the 24 pro-democracy international students studying at Australian universities interviewed by Human Rights Watch, 11 from mainland China and 13 from Hong Kong, over half reported direct harassment and intimidation from fellow classmates from China. These included threats of physical violence, threats of being reported to Chinese authorities back home, being doxed online or threatened with doxing. Doxing is when personally identifying information about someone is shared online without their consent.[58] These acts occurred in a mix of environments, including online, in-person, and on and off campus.

Students said they were targeted for harassment and intimidation after their classmates from China identified them as critical of the Chinese Communist Party, expressing support for democracy in Hong Kong or China, or if they attended a protest in support of Hong Kong democracy.

Most pro-democracy students interviewed who experienced harassment and intimidation said they did not report it to their university. Those who did not report these incidents cited their belief that their university would not take the threat seriously or that they feared their university was sympathetic to pro-Beijing Chinese students only.

Human Rights Watch has documented that the harassment, surveillance, and intimidation of pro-democracy students from China has steadily increased in Australia in the past decade.[59] Pro-Chinese government students and social media users have also subjected academics to harassment, intimidation, and doxing if the academics are perceived to be critical of the CCP or discuss sensitive issues such as Taiwan, Tibet, Hong Kong, or Xinjiang.

Those interviewed generally believed monitoring and surveillance of students by Chinese government officials and individuals supportive of the CCP is prevalent in Australia. Several students described how Chinese officials had monitored their activities in Australia or been informed about them, which then led to authorities questioning their family members in China about their actions.

Harassment and Intimidation of Students

In mid-2019, as massive pro-democracy protests filled the streets of Hong Kong, many of the approximately 15,000 students from Hong Kong studying in Australia wanted to express their solidarity with their families and citizens back home.[60] On campuses and in city squares across Australia, these students organized demonstrations and speeches, highlighting their concerns at Beijing’s tightening grip on Hong Kong and the growing police violence that left many protesters injured and hundreds arrested. Protests were held in Melbourne, Sydney, Canberra, Perth, Adelaide, and Brisbane. Most were organized and led by university students from Hong Kong studying in Australia.[61]

The aftermath of these protests on and off Australian university campuses resulted in many instances of harassment and intimidation of pro-democracy Chinese and Hong Kong students by fellow students. The very participation of students in these pro-Hong Kong solidarity events “outed” the political views of students to their peers.

A female student from China, Zhang Xiuying, who joined in a demonstration to support democracy in Hong Kong, received a threatening message from a fellow PRC student just hours after attending the demonstration. She said:

At around 2 a.m. I received a message from a mainland classmate. He was like, “I’m watching you.” He ended the conversation with, “I support the Hong Kong police.” I knew him for a long time, and I knew he had different opinions. I had told him before, “I didn’t want to talk about Hong Kong stuff with you.” Personally, I felt really scared. I went to go see the uni [university] psychologist because I was so stressed. I blocked him [the classmate] on Facebook. I was in a course with 98 percent mainland students. Students were bad-mouthing me. That I was not loyal to the country.[62]

Zhang Xiuying said that she did not feel comfortable reporting the threat to her university because she said she felt that they would not take the threat seriously and she perceived her university as only being sympathetic to pro-Beijing Chinese students.

“In their mind, Chinese-speaking students are pro-CCP and they don’t want to hurt their relationship with the Chinese student association,” Zhang Xiuying said.[63]

While some students received anonymous threats, others were also the subject of doxing attempts online by fellow students. A male student, Wang Wei, who supported the Hong Kong democracy protests, said social media users threatened him as well as circulating his name online and leaking elements of his address:

There were attempts to dox me and someone leaked the name of the building I was living in as well as the floor number (although they didn’t get the floor number right) online. There were many rumors circulating on WeChat claiming that I have been beaten up and hospitalized. Another post said, “The CBD [Central Business District] has many dark alleys without CCTV and these will be good places to attack him.” I was recognized in the lobby of my apartment once, although he just asked me, “Have all Hong Kongers died yet?” and left the building.[64]

Wang Wei did not report these threats to his university. He said this was because he felt that his university was too worried about getting “one step wrong” and the impact this could have on “Chinese students who were the biggest customers.” However, he reported the incident to the local police: “I went to the police station to report these threats. However, the officer in attendance was unable to file a report because he said the people who posted these threats could not be identified.”[65]

Adam, a PRC student who attended a pro-Hong Kong democracy rally off campus, described what happened to him at the protest and in the days after:

They [the counter-protesters] were taking photos of us. One of the Chinese guys that I knew, he was a bartender, and I was a security guy at this bar, and after that protest he sent me pictures of me on Chinese social media and he said, “I didn’t know you support Hong Kong.” And he said, “If I tell my family and my friends about you being there, you will become so famous.” I said, “Don’t threaten me like this, I thought you were my friend.” And then he said, “I was just joking, man.” After that we stopped talking.[66]

Violence also flared at some smaller campus demonstrations. One student described how she reported an assault by pro-Chinese government protesters: “We reported to the university as one of the Chinese interveners acted up and tried to hurt our protesters. The security team came and separated us.”[67]

One of the largest pro-Hong Kong democracy demonstrations was held at the at the University of Queensland (UQ) on July 24, 2019, with hundreds of students gathering in UQ’s “Great Court” at lunchtime. A student journalist speaking to The Guardian estimated there were initially about 50 Hong Kong international students and 100 or more Australian students attending, before around 200 or more pro-Chinese government counter-protesters arrived.[68]

The Guardian reported that the pro-Chinese government students “interrupted the sit-in, tearing down banners, punching and shoving.”[69] One of the Hong Kong student organizers, Nelson, said:

We were being peaceful and suddenly there is a group of Chinese students around us. Hundreds of them. They got their speakers and slogans, and they seem well prepared and organized. Three of them surrounded my friend and they assaulted him. The police and security came. One of my Hong Konger friends got choked around the neck and one of my friends wearing a Hong Kong student association hoodie got bullied by three Chinese students. They cornered him in the carpark in the dark and intimidated him. It was really threatening.[70]

Videos posted on social media showed shouting and abuse between the two sides, turning into physical violence with police arriving to break up the four-hour-long standoff.[71] The Queensland police told Human Rights Watch they received no “formal” complaints, and therefore no charges were made in relation to the July 24 protest. The University of Queensland issued a statement regarding the protest on the afternoon on July 24:

One of the roles of universities is to enable open, respectful and lawful free speech, including debate about ideas we may not all support or agree with. The University expects staff and students to express their views in a lawful and respectful manner, and in accordance with the policies and values of the University. Earlier today, in response to safety concerns resulting from a student-initiated protest on campus, the University requested police support. On the advice of police, protestors were requested to move on. The safety of all students is paramount to the University. Any student requiring support should contact Student Services.

The statement was sent to media groups and put on the university’s Facebook page.[72] The university sent a copy of their statement that evening to the Chinese Consulate in Brisbane. The next day, Consul-General Xu Jie, who had controversially been appointed several weeks earlier as an honorary adjunct professor of language and culture at the University of Queensland, praised what he called the “spontaneous patriotic behavior” of the counter-protesters.[73] At the time, the university did not criticize the consul-general’s comments.

In September 2019, UQ’s Vice-Chancellor Peter Høj told the ABC that, “I’m not in the issue of debating with diplomats, and, but I made it very clear that, we don’t endorse any violence acts in a peaceful demonstrate [sic], and through that you can conclude that I would disagree with somebody who would endorse that type of behaviour.”[74] It wasn’t until 11 months after the comments by Consul-General Xu Jie that the UQ chancellor, Peter Varghese, publicly labelled them as “unacceptable.”[75]

In the days after the protest, Chinese state media outlet Global Times published the full real name of Nelson, the Hong Kong student who helped organize the rally at the University of Queensland. The student was then doxed online, with his real name and photo published on Chinese social media sites Weibo and WeChat in the days after the event. Nelson told Human Rights Watch:

After this my name got doxed. My full name and my photo, a really close-up photo. It was really scary for us. At the beginning we didn’t wear masks and we didn’t think there was a big threat. After that incident I was easily recognized on campus and felt like I was being followed and they were looking at me. I’m worried about being doxed again and the intimidation. I changed my name on Facebook. Sometimes I feel like I am being watched on campus.[76]

Nelson said he did not report what happened to the University of Queensland, citing the university’s failure to criticize previous intimidating actions by Chinese nationalist students on his campus: “We have not reported it to UQ as we’ve seen how UQ deals with our Lennon Wall being ripped apart by Chinese students.[77] We don’t think UQ would help us, like they’d just want to put down the incident to cause less trouble.”[78]

Human Rights Watch interviewed three pro-democracy students from China and Hong Kong who participated in the University of Queensland protests on July 24, 2019. All three said they felt that the university did not adequately respond to the events at the time.

The University of Queensland told Human Rights Watch that “in the past three years, we have not had any formal complaints from students or staff” relating to Chinese government harassment, surveillance or threats on campus, but confirmed they had received four complaints making allegations about UQ students in relation to “conduct broadly in the nature of ‘doxing.’” UQ confirmed that they did take action in respect to three complaints and that one is still being investigated. The parties involved “are from diverse countries of origin,” the university wrote.[79]

One year after the protests and following intense criticism of UQ’s handling of events and the university’s close relationship with the Chinese consul-general in Brisbane, the university leadership announced several new measures to limit Chinese government interference.[80]

These include ensuring that the university’s Confucius Institute, a Chinese government-funded language institute, no longer had any involvement in credit-bearing courses. UQ’s senate also ruled that serving foreign government officials will no longer be offered honorary or adjunct positions at the university—a direct response to the controversy around the Brisbane Chinese consul-general given an honorary professor title at UQ in 2019. At the time of writing, Consul-General Xu retained his honorary position at the university, which is due to end in December 2021.[81]

The university says it has also increased its liaison with the Queensland Police to develop a strategy for “ensuring that any further protests remained peaceful and safe for all students,” as well as arranging for enhanced security on campus for protests. UQ says it has also conducted “online and physical initiatives to reinforce campus harmony and tolerance,” employed additional student casual staff to speak to concerned students and offer peer-to-peer support, and formed a “community operations group” consisting of representatives from Student Affairs, Security, and the Student Union to meet on a regular basis and advice the deputy vice-chancellor on concerns among the student population.

Regarding an internal investigation into the July 2019 protest at UQ, the university told Human Rights Watch that while it requested 10 students to provide statements and other evidence about the protest, only three came forward to do so. The university advised that “in the end, UQ’s investigation did not uncover sufficient information to indicate that any UQ students engaged in inappropriate conduct,” and therefore no disciplinary action was taken.[82]

UQ also disclosed to Human Rights Watch that it had separately investigated “a number of reports of vandalism” in relation to the Lennon Walls on campus. “Nine of these reports resulted in UQ students being identified and actions taken by the university,” UQ said.[83]

Despite threats and violence at UQ, Hong Kong and Chinese students and their Australian supporters continued to hold demonstrations in Brisbane. At another protest in September 2019, Fung, a recently arrived student from Hong Kong was introduced to the crowd as a “real Hong Kong protester.” Recently arrived and feeling a long way from Hong Kong, Fung felt comfortable standing on stage at the rally without a mask. Fung told Human Rights Watch that about three weeks later, when leaving his home in a suburb of Brisbane, he found four Mandarin-speaking men waiting in front of his home:

One of those men called my name in a very angry way. So me and my friend ran away. They said, “Don’t go, stay there!” They picked up sticks and they were wearing masks. Not like a surgical mask, a hiking scarf that was put up to cover the bottom of the faces. They were about 30 meters away from me and they started to come after me and shouted and so I ran. I live on a hill and I ran down for 10 minutes and they didn’t chase. I was so scared after this incident I stayed with my friend for several days and didn’t come back home. I moved out to rent another place a week later. I slept in my car for two or three nights because I didn’t want to go back there.[84]

Fung was attending an English college at the time, and he said he did not feel comfortable reporting the incident to his school. But at the insistence of a flatmate, he reported it to local police. He said:

My flatmate took me to the police station to report the case in November. And the police said to me because of where I live, they don’t have any CCTV. But they wrote down what happened. The police officer hasn’t called me back. They said it’s very difficult to determine who chased me, that it would be impossible.[85]

Another student, Amy, told Human Rights Watch that mainland students who tried to stand up for Hong Kong protesters at a rally in Melbourne were among those doxed:

There was a Chinese student at the rally who tried to explain to other Chinese students that we were not promoting Hong Kong Independence—we were protesting the extradition law at the time—and eventually she got bullied, verbally insulted and they shared her personal information online because she was considered a “treason.”[86]

At the University of Technology (UTS) in Sydney, a cartoon written in Chinese with a death threat directed at pro-Hong Kong protesters was removed only after an ABC journalist brought it to the attention of campus security.[87] The cartoon, put up on a Lennon Wall near the university’s main entrance, showed a man holding another man over a cliff with the caption: “Take back your Hong Kong independence speech if you don't want to die.”

In Perth, a Hong Kong university student organizer told the ABC that police tipped her off that she had been filmed at a pro-Hong Kong democracy rally.[88] She said she had been followed home by Chinese nationals and had received death threats. A male student told the ABC he too had been doxed and followed in the wake of the Perth rally. Both students declined to be interviewed by Human Rights Watch about their experiences, citing the passing of the national security law in Hong Kong.

|

Hong Kong’s National Security Legislation On June 30, 2020, the Chinese government in Beijing passed a sweeping new National Security Law for Hong Kong that has been used to prosecute peaceful speech, curtail academic freedom, and generate a chilling effect on fundamental freedoms in the city.[89] The law contains provisions that are already proving devastating to human rights protections in Hong Kong. These include creating specialized secret security agencies, denying fair trial rights, providing sweeping new powers to the police, increasing restraints on civil society and the media, and weakening judicial oversight. The extraterritorial reach of the National Security Law means the law also applies to offenses committed against Hong Kong “from outside the Region by a person who is not a permanent resident of the Region.”[90] |

A mainland pro-democracy Chinese student, Lim, said that he had been threatened on campus while standing in front of his university’s Lennon Wall:

Just in front of the Lennon Wall, I was contacted directly by a senior Chinese student. He threatened me in a number of ways. He was an international student representative. I reported it to the student’s organization. They said they would contact him. Actually, he did not contact me again. I only reported it to the uni administration, not police.[91]

Lim says he was never informed by the student association regarding what action, if any, was taken against the student who threatened him. Human Rights Watch wrote to his university asking if they had any record of this complaint but received no response.

In August 2020, the University of New South Wales (UNSW) published an article about Hong Kong’s national security law on its media page with quotes from Elaine Pearson, Human Rights Watch’s Australia director and an adjunct lecturer at UNSW’s law school. UNSW removed the article in reaction to a campaign of harassment against the university and Pearson by pro-Chinese government students.[92] The article was later reinstated, but only on the law page of the website. In discussing this incident, a student at the university was openly harassed in a UNSW law student WeChat group after expressing sympathy for Hong Kong. “I have screen capped this and sent it to the [Chinese] embassy,” replied his classmate to the WeChat group, which contained 177 students.[93]

A mainland pro-democracy student who was a member of the WeChat group, said:

We had a WeChat group for Chinese law students just to share some study information. Some students got very angry about the article and wanted an apology. There was a Chinese student who was pro-democracy, and he expressed his view in the group chat. And he said he stands with the professor and with Hong Kong. And they threatened to report his speech to the embassy. They kicked that pro-democracy student out of the group chat. Only one person had the guts to speak out.[94]

Other demands and insults were tweeted at the university’s official Twitter account by people who openly identified as UNSW students on their social media profiles.

“Annihilate English dog, Destroy Hong Kong independence,” wrote a young male student. “Refund this year’s school fees for Chinese international students, apologize to all Chinese international students, fire all teaching staff who made such statements, head of UNSW must resign, expel all ‘yellow’ Hong Kong international students.”[95]

While UNSW’s Vice-Chancellor Ian Jacobs affirmed the university’s commitment to free speech and academic freedom in a statement on August 5, it was in general terms and did not mention the words “China” or “Hong Kong.” It also initially only went to UNSW staff. Five days later, the statement was made available on the university website.[96]

Following this incident, Human Rights Watch wrote to and met with UNSW management and urged the university to hold a public online meeting to clarify academic freedom to students and staff. Human Rights Watch also urged the university to conduct a thorough investigation into the online campaign targeting the university to determine who organized it, whether any are UNSW students, and whether UNSW students were involved in intimidation, harassment, or threats to inappropriately report discussions to off-campus authorities such as the Chinese consulate.

Human Rights Watch asked UNSW if it had reprimanded any students over such comments. In response, UNSW advised that they were “not able to provide details of the complaints currently lodged in our Complaints Management System but can advise that we do not currently have any complaints registered” in relation to the online harassment and intimidation of staff and fellow students following the outcry over the Hong Kong article published in August 2020.[97]

UNSW said that “complaints raised following the Hong Kong article published on Twitter in August 2020 were of a general nature relating to UNSW’s response to the incident and were not directed towards individual students.”[98]

To date, the university has not publicly released the results of any investigation into the incident nor confirmed what investigation, if any, took place. Vice-Chancellor Ian Jacobs told Human Rights Watch that “I have already made a public statement on UNSW’s handling of that matter and have taken steps to ensure that such an incident will not happen again.” However, he has not indicated what new policies UNSW has adopted to ensure similar incidents do not occur again.[99]

In February 2021, Freedom of Information documents revealed that a confidential report to the UNSW board recommends the university adopt a “more assertive, forward-leaning approach to China engagement” and “position UNSW as a leading advocate for constructive engagement with China.” The report was delivered only months before UNSW was embroiled in the censorship controversy.[100]

Teaching over Zoom, which became standard during 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, also presented the opportunity for a new type of harassment within the online classroom.

In August 2020, Hong Kong students in a chat group at a Melbourne university were warned by fellow students that a mainland classmate had harassed and intimidated a young female student, after he noticed a Hong Kong revolution flag in her bedroom during a class Zoom call.

Said Jonathan, a student, “[T]he mainland classmate started to private message and harass her. He said he was recording it and would put the video up on TikTok.”[101]

The student who was the alleged target of the harassment did not want to speak to Human Rights Watch directly due to security fears.

Only one of the 24 pro-democracy students interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that their university had discussed a point of contact or how these kinds of political pressures, threats, or acts of retaliation can be privately or anonymously reported. Every other student reported that their university had never raised this. A few students remarked that this was in sharp contrast to the policies on sexual harassment: Zhang Xiuying said, “I know you could report sexual harassment. But I didn’t know threats from Chinese students [could also be reported].”[102]

Harassment and Intimidation of Academics

Pro-Chinese government students and social media users have also subjected academics to harassment, intimidation, online abuse, and doxing if perceived to be critical of the Chinese Community Party or discuss sensitive issues such as Taiwan, Tibet, Hong Kong, or Xinjiang.

These incidents are not just political disagreements or heated exchanges in class. Academics have been subjected to doxing, the release of their personal information online, which is then amplified and shared, and the basis for targeted abuse. They have also been targeted with direct threats and complaints to employers about their suitability to hold their position and by bringing particular academics and their universities to the attention of the Chinese embassy or consulate.

|

In August 2020, a Taiwanese engineering student enrolled at a university in Melbourne joined his tutorial discussion over Zoom. The student was the only Taiwanese student in a class in which about 20 to 25 students were from mainland China. Studying remotely due to Covid-19, the Taiwanese student was discussing the class assignment, which involved walking around his neighborhood in Taipei. During this chat, the student mentioned Taiwan as a country. In response, a mainland classmate messaged the student, thinking it was private but sending it to the whole class, telling him that Taiwan was not a country and that he should not refer to it as such. The class tutor told the mainland Chinese student that his language was inappropriate. Another tutor in the engineering course, after learning what happened, wrote a post to students in the division, cautioning of the need to tolerate and respect others. Human Rights Watch saw a copy of the post which included the following: Dear Students, I was appalled to hear about the behavior of one student today in this subject. This person publicly denied the existence of the country where another student in the class is from and currently lives. Here at [university location withheld] we celebrate the diversity of international countries of origin that our students and staff are from. This includes Australia, Taiwan (Republic of China) and China (People’s Republic of China) and many other national states. Please take this opportunity in a tutorial class to learn from each other and meet people from different backgrounds to grow and become a more mature and enlightened adult. We all need to ensure that the learning environment is inclusive and welcoming to our diverse staff and student cohort.[103] Soon, the tutors began to receive emails from Chinese students angered by her message. News of what the tutor said began circulating on Chinese social media, where she was doxed with her name, email, and course information. One of the emails sent to the tutor, which the sender also copied to the university’s vice-chancellor said: I’ve seen your email about Diversity through a very famous Chinese social media and now many Chinese students know what you publicly said. I think it’s really bad as now we Chinese had a bad impression to [University name withheld] because of YOU. I know everyone has his/her own political idea, but I don’t think you should express it by sending this kind of email to many students. I’m now seriously concerned about how this thing will go on, and I firmly ask you for public apologize. Otherwise, I think not only myself, but many Chinese will not recommend [University name withheld] as it does not respect Chinese.[104] The tutor was advised that her message to students had been spotted on WeChat by academic colleagues in China. Several students interviewed separately confirmed they were aware of this incident through WeChat. Concerned for her safety, the university removed the original post and temporarily removed all the tutor’s public details and contacts from their website. The incident was reportedly dealt with quietly and Human Rights Watch is not aware of any wider policy changes or reviews in response. Following the incident, the Taiwanese student decided he did not want to present his assignment to the class, telling the tutor he did not feel comfortable and that he was worried about “inflaming an argument.” |

Merely mentioning Taiwan as a separate political entity was identified by several academics as a cause of harassment and intimidation. “K,” an academic who specializes in China and teaches Chinese students, said:

Whole areas are becoming off limits. I have a colleague who had students’ complaining about content of classes, due to mentioning Taiwan. Another colleague had a guest lecturer who mentioned Taiwan. Even saying that Taiwan could be a political entity was enough for some Chinese students to lodge complaints against the lecturer for inviting the guest.[105]

This academic explained that they and their colleagues worry about numerous student complaints because it can result in the tutor receiving low scores on their Subject Experience Survey (SES), an online feedback system in which students give feedback on their courses and teachers. Said “K”: Because if those students will give you low SES scores and if you have a lot of low scores, those scores will be on your record and when it comes to your own promotion it has an impact.”[106]

Most academics interviewed said their university had no adequate response to this kind of harassment or any policy to deal with it. Instead of directly addressing the issues, with universities proactively explaining the lines of acceptable behavior to students, these incidents tended to be quickly swept under the carpet with institutions simply muddling through until the next time. The systemic failure to respond at a policy level has a direct correlation to the self-censorship academics feel forced to practice that is discussed in Section III of this report.

Said “K”:

The universities are behind the curve on all of this. There is not a strategy for dealing with it. In internal meetings for the last few years, it’s been raised by more and more departments. More and more people are having these problems. At our uni there hasn’t so far been any strategy.[107]

The online targeting and harassment of academics in Australian universities who have strong public opinions on issues deemed sensitive to the CCP has become common online in the last 10 years on Twitter. There is evidence that this online harassment then sometimes extends into academic’s daily lives. An academic became the subject of a targeted email harassment campaign beginning in 2018 after giving public interviews critical of the Chinese Communist Party. The academic said:

I haven’t shared this before, but since December 2018 I started getting harassing emails on an almost daily basis. They set up a fake Gmail account in a name of someone I knew. They said, “Oh, you’re coming to your end.” And then last year in December, whoever this person is actually set up an email in my name and sent a fake resignation letter to my entire school. I was at home having a BBQ and I got a phone call from the head of my department, who said they were sorry to hear me go. I didn’t bother going to police over threatening emails. When I went to them over the resignation email, which is fraudulent activity, the police seemed very uninterested. For a little while there I thought it might be one crazy guy, but the police did say that the sheer amount of emails sent seems to indicate that it’s not just some lonely crazy guy in his basement.[108]

Students and academics told Human Rights Watch that classroom disturbances and arguments when controversial issues relating to China were discussed were not unusual.

“R,” an academic who specializes in China and teaches Chinese students, told Human Rights Watch:

We have had attempts to shout down students. Chinese PRC students shouting down Hong Kong students in class, talking about the Hong Kong independence movement. I told them it was inappropriate. You have to be a really good negotiator to stop problems popping up.[109]

In January 2021, the Chinese language pro-CCP online media outlet Today Melbourne featured the case of two Chinese students at Monash University who complained after two articles assigned by their tutor for their Data in Society class referenced oppressive digital surveillance of Muslim citizens in China’s Xinjiang region.[110] The articles were from the acclaimed academic journal Nature, one entitled “Crack down on genomic surveillance,”[111] and the other “The ethical questions that haunt facial-recognition research.”[112]

“The articles slander the Chinese government, spread rumors, sow discontent between ethnicities, and have a strong anti-China sentiment,” the Monash students told the online website.[113]

The students said that 95 percent of the students enrolled in the summer semester class were PRC students and that by selecting these articles as recommended readings, they believed that the tutor was “seriously disrespecting the students.”

Today Melbourne wrote that some of the Chinese students had already contacted the Chinese embassy and “the school management and demanded the retraction of the readings.”[114] The website published the email that had purportedly been sent by the Monash University tutor to the students who complained and Human Rights Watch has verified its authenticity:

Hi all,

I’m sorry you have found the content of some of the articles so distressing. The idea behind critical thinking is as you say—to identity and evaluate arguments made by others. Sometimes these arguments will be flawed. It is your job to identity these flaws and point them out by drawing on evidence (including anecdotal evidence).

Unfortunately, we all know there is a lot of misinformation out in the world, part of this assignment is about you being able to identity misinformation and respond in a constructive way. If you feel there are errors of fact in the article you were assigned, please feel free to say so in your assignment and explain how you know they are incorrect.

The nature of ethics is intrinsically political, so most of what is taught in this unit can be explored from a political perspective. The unit takes a socio-political perspective and draws on concepts from a range of fields including philosophy and sociology (both quite political). I hope you understand then that political content is unavoidable.

Human Rights Watch wrote to Monash University inquiring about this incident.[115] The university responded, confirming what had happened and saying that its response upheld “academic freedom and freedom of speech.”[116]