Summary

“I am a mechanical engineer and I was interviewed for a position in Iran's oil and gas fields […]. My contact in the company told me that they really liked me, but that they did not want to hire a woman to go to the field.”

− Naghmeh, a 26-year-old woman from the city of Tehran

“I often impress my boss through points I raise about programming, but I rarely get the chance to participate in the decision-making process. Once my boss told me to come and explain my points in a meeting, but then he immediately retracted his suggestion, saying that it’s not a good idea since it’s a men’s club.”

− Safoura, who works for consulting company in Tehran

In July 2015, Iran, the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council Germany, and the European Union (EU), reached an agreement on Iran’s nuclear program. This resolution marked a historic breakthrough in which Iran began to re-engage with and re-integrate into the global economy. In the first six months of 2016, trade between the EU and Iran – described by the United Kingdom Secretary of State for International Trade as “the biggest market to enter the global economy since the fall of the Soviet Union”– increased by 43 percent. President Hassan Rouhani, who championed the deal, promised that all Iranians would benefit economically as a result. Yet without serious reforms to Iran’s legal code and labor regulations, Rouhani’s rhetoric will remain detached from the daily reality of a critical constituency in Iran and one which makes up half of the country’s population: Iranian women.

Women in Iran confront an array of legal and social barriers, restricting not only their lives but also their livelihoods, and contributing to starkly unequal economic outcomes. Although women comprise over 50 percent of university graduates, their participation in the labor force is only 17 percent. The 2015 Global Gender Gap report, produced by the World Economic Forum, ranks Iran among the last five countries (141 out of 145) for gender equality, including equality in economic participation. Moreover, these disparities exist at every rung of the economic hierarchy; women are severly underrepresented in senior public positions and as private sector managers. This significant participation gap in the Iranian labor market has occurred in a context in which Iranian authorities have extensively violated women’s economic and social rights. Specifically, the government has created and enforced numerous discriminatory laws and regulations limiting women’s participation in the job market while also failing to stop – and sometimes actively participating in – widespread discriminatory employment practices against women in the private and public sectors.

Discrimination against women in the Iranian labor market is shaped in part by the political ideology that has dominated Iran since the Islamic revolution, which pushed women to adopt perceived “ideal roles” as mothers and wives and sought to marginalize them from public life. Yet what often goes unmentioned in narratives on women’s role in Iranian society is that discriminatory laws towards women in the economic realm long predate this period. Many discriminatory laws can be found in Iran’s 1936 civil code. After the Islamic Republic of Iran came to power in 1979, the authorities rolled back the progress made by legislation enacted in 1976 promoting gender equality, particularly in family law, and returned to these earlier legal provisions while also enforcing a dress code as a prerequisite for appearing in public life. In the past three decades, authorities have punished women’s rights activists for their efforts to promote gender equality in law and practice, including with imprisonment. The government’s prosecution of prominent members of the “One Million Signatures” campaign to change these discriminatory laws also illustrates that the battle for women’s social and economic freedoms cannot be disentangled from the broader struggle for political and civic rights in Iran.

Despite their everyday struggle against this discriminatory environment, many Iranian women have thrived in higher education; they represent the majority of test takers in the national university entrance exams. The uphill climb for women, however, only gets steeper as they seek entry into and promotion within Iran’s job market. Unemployment for women is twice as high as for men, with one out of every three women with a bachelor’s degree currently unemployed. The participation of women in Iran’s job market is significantly lower than the average participation in other upper-middle income countries and is lower than the average for all women in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. MENA already has the lowest female participation compared to other regions at around 20 percent.

Iranian law is likely a culprit in creating this unequal economic reality. Domestic laws directly discriminate against women’s equal access to employment, including restricting the professions women can enter and denying equal benefits to women in the workforce. Furthermore, Iranian law considers the husband the head of the household, a status that grants him control over his wife’s economic choices. For instance, a husband has the right to prevent his wife from working in particular occupations under certain circumstances, and, in practice, some employers require husbands and fiancés to provide written consent for women to be allowed to work with them. Lawyers told Human Rights Watch that, during divorce court proceedings, husbands regularly accuse their wives of working without their consent or in jobs they deem unsuitable. A man also has the right to forbid his wife from obtaining a passport to travel abroad and can prevent her from travelling abroad at any time (even if she has a passport). Some employers interviewed said they were unlikely to hire women where extensive travel is involved due to the uncertainty created by these discriminatory legal codes.

The government also fails to enforce laws designed to stop widespread discrimination by employers against women, and Iranian law has inadequate legal protections against sexual harassment in the workplace. Moreover, while Iranian law prohibits discrimination against women in the workplace, its application is not extended to the hiring process, where it is critically needed. Publicly available data shows that government and private sector employers routinely prefer to hire men over women, in particular for technical and managerial positions. Employers in both the public and the private sectors regularly specify gender preferences when advertising position vacancies and do so based on arbitrary and discriminatory criteria. Managers and employees interviewed told Human Rights Watch that they were not aware of any anti-sexual harassment policies at their place of employment, while several women reported intances of sexual harassment. Moreover, interviewees regularly expressed frustration with arbitrary enforcement of discriminatory dress codes.

Iranian laws also impose severe restrictions on the freedoms of assembly and the right to form trade unions, which limit workers’ ability to advocate collectively for their rights and weakens the effectiveness of existing complaint procedure mechanisms.

Instead of taking steps to address these barriers, since 2011 Iran has shifted its population policies towards increasing population growth in a manner that has placed a disproportionate burden on women in the society. As a result, several draft bills that aim to increase child bearing do so mostly by restricting women’s access to reproductive healthcare and employment opportunities. If passed, these bills could further marginalize women in the economic sphere.

Some Iranian officials have recognized the lack of gender equality as a problem. During his presidential campaign in 2013, President Rouhani rejected gender discrimination and stated that his administration will ensure equal opportunity for women. Since taking office, however, his administration has taken only minimal steps to improve the situation, such as by temporarily suspending certain government hiring processes that were discriminatory against women.

Shahindokht Mowlaverdy, the vice president for Women and Family Affairs, has spoken out against gender discrimination, promising, among other things, to create exemptions for women to travel abroad for work on certain occasions without the permission of their husbands. However, her efforts are yet to translate into tangible benefits for Iranian women.

At the height of Iran’s confrontation with the international community over its nuclear programs between 2007 and 2013, the economic sanctions imposed by global powers, combined with changes in Iran’s monetary policy, negatively impacted the economy and resulted in higher levels of unemployment and the closure of numerous businesses. Employment data show that under this difficult situation, women suffered disproportionately.

Since Iran and world powers reached the historic nuclear deal in 2015 and the subsequent removal of several sanctions, the Iranian government’s first priority has been to improve the country’s economy. Several foreign companies have resumed trade with Iran and are in the process of opening their offices there. But for women who lost their jobs under the previous decade’s difficult economic circumstances and are struggling to be treated equally in the job market, the effect will be limited unless the barriers confronting women are addressed.

Iran needs to adopt comprehensive anti-discrimination law to eliminate discrminatry provisions of the current legal system and to extend equal protections to women who participate in the job market. If the administration is serious about removing barriers to equal participation of women in the workforce, it should work closely with the parliament to enact legislative reforms, to address prevailing gender stereotypes in the workplace, and to work towards extending social insurance coverage to those in the informal economy which has become more female dominant. Only when these right restrictions are addressed will Iranian women be able to take equal part in building the future of their families and their country.

Recommendations

To the Iranian Government and Parliament

- Ratify the Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) without reservations.

- Ratify International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 87 on Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize (1948), No. 156 on Workers with Family Responsibilities (1981), and No. 183 on Maternity Protection (2000), to provide a broader, more equal framework governing the labor force.

- Move towards abolishing or amending all laws and other legislation under the civil code that discriminate against women when it comes to the right to work, including but not limited to:

- Article 1117 of the civil code, which allows a husband to prevent his wife from obtaining an occupation he deems against family values or his reputation.

- Article 18 of the passport law, which allows a husband to refuse permission to his wife to travel. As an interim measure, judicial authorities should waive the requirement for women traveling for work until that requirement is abolished entirely.

- Revise marriage contracts to guarantee equal rights for women, in accordance with international human rights law. As an interim measure, make all those provisions optionally available in marriage contracts at all official marriage registration offices.

- Pass a comprehensive anti-discrimination law which bans all forms of discrimination on the grounds of gender in the workplace, in both the public and private sectors, and includes prohibitions against indirect discrimination consistent with the definition of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, while providing effective mechanisms for complaints, litigation, and implementation for women who bring complaints. The proposed legislation should specifically include reforms to the Labor Code and Social Security Law to:

- Explicitly prohibit gender specifications in job advertising.

- Ensure that state agencies do not conduct discriminatory recruitment practices and cease the use of gender-specific job advertising.

- Establish penalties, including fines, against companies and state agencies that discriminate against women, including in recruitment and promotion processes.

- Protect women from sexual harassment, including in the workplace.

- Grant women and men equal protection and benefits, including but not limited to “family bonuses.”

- Provide similar family leave benefits for fathers and men related to elderly or sick relatives.

- Revise relevant bills currently before the parliament to remove all discriminatory provisions, including the Comprehensive Family Excellence Plan, the Plan to Increase Childbirth and Prevent a Decline in Population Growth, and the Plan to Protect the “Sanctum” of the Hijab.

- Respect the rights of workers to associate, organize, and form unions, and to peaceful assembly with others in accordance with international human and labor rights law.

To the Iranian Ministry of Labor

- Accept and investigate sexual harassment and other complaints of discrimination submitted to the existing complaint procedure bodies within the ministry.

- In collaboration with the Office of the Vice President for Women and Family Affairs, workers’ unions, and employers organizations, develop and ensure the principle of “equal remuneration for work of equal value,” in accordance with ILO regulations.

- In collaboration with the Office of the Vice President for Women and Family Affairs, address prevailing gender stereotypes in the workplace, including through awareness-raising campaigns.

- Progressively extend social insurance coverage to those in the informal economy and, if necessary, adapt administrative procedures, benefits and contributions, taking into account their contributory capacity.

To the International Labour Organization

- Call on Iran to ensure that the Iranian labor code fully complies with international standards regarding nondiscrimination and equal treatment in employment.

- Provide trainings to inspectors at the Ministry of Labor and other government officials on gender-specific labor rights issues and investigative techniques.

To National and Foreign Companies

- Adopt comprehensive anti-discrimination policies which bans all forms of discrimination on the grounds of gender in the workplace and specifically includes:

- Clear policies prohibiting sexual harassment in the workplace, and conduct periodic trainings on those policies; and

- Ensuring gender equality in hiring and promotional practices as well as equal access to professional development opportunities.

To the European Union (EU), EU Member States, and Other Third-Party States

- Ensure the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, in particular its non-discrimination principles consistent with other relevant international human rights and ILO standards, remain an integral part of any economic engagement with or investment in Iran.

Methodology

The Iranian government has rarely allowed international human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch to enter the country to conduct independent investigations into abuses over the past 30 years. Iran’s record on independent criticism and free expression more broadly has been dismal, particularly over the past decade. Hundreds of activists, lawyers, human rights defenders, and journalists have been prosecuted for peaceful dissent. Iranian citizens are often wary of carrying out extended conversations on human rights issues via telephone or email, fearing government surveillance that is widespread across social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and the Telegram messaging application. Authorities often accuse their critics inside Iran, including human rights activists, of being agents of foreign states or entities and prosecute them under Iran’s national security laws.[1]

For this report a Human Rights Watch researcher interviewed 44 women and men, including lawyers, small business owners, hiring managers, employees in public and private sectors, and economic experts who currently live in Iran or have recently left the country and have participated in or have studied Iran’s job market. A large number of interviewees were from the city of Tehran but a number of others lived and worked in cities such as Shiraz, Mashhad, Sanandaj, and Qazvin. Where available, Human Rights Watch incorporated government statistics and officials’ statements into this analysis. Human Rights Watch interviewed men and women from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds, but the majority of interviewees were university graduates and members of the highly skilled segment of Iran’s labor force. The Human Rights Watch researcher conducted all of the interviews in the Persian (Farsi) language over secure messaging smartphone applications. All participants were informed of the purpose of the interview and the ways in which the data would be used and were given assurances of anonymity. This report uses pseudonyms for all interviewees except one and withholds other identifying information to protect their privacy and their security. None of the interviewees received financial or other incentives for speaking with Human Rights Watch.

On March 14, 2017, Human Rights Watch sent lists of questions to the Iranian Parliament, the Office of the Vice President for Women and Family Affairs, and the Ministry of Labor, and requested meetings to discuss the report’s findings prior to publication (See Annex I, II, and III). Human Rights Watch has not yet received a response.

Human Rights Watch also corresponded with two foreign companies that are currently operating in Iran or have announced that they will begin commercial activities in the country in the near future inquiring about mechanisms in place to ensure gender equality in practice.

Human Rights Watch makes no statistical claims based on these interviews regarding the prevalence of discrimination against the total population of women in Iran.

I. Background

During the 1979 revolution, Iranian women from different backgrounds stood shoulder-to-shoulder with men in demanding greater respect for human rights. Thirty-eight years later, however, women are still fighting, both for equal recognition before the law and against discriminatory patriarchal social practices and norms. The dominant ideology of the period following the Islamic Revolution promoted a regressive view of women’s role in society. It assigned women primary responsibility for child-raising and work inside the home and placed serious obstacles for women seeking to participate in society on the same level as men. As will be elucidated in greater detail in the chapter on violations embedded in Iranian law, the authorities also revived a decades-old civil code embedded with discriminatory provisions against women in key legal matters such as marriage, family law, age of criminal responsibility, inheritance, court testimony, and the issue of diya’, or “blood money.”

Yet these restrictions have long been in tension with the talents and aspirations of Iranian women and national economic necessities. During the devastating eight-year war with neighboring Iraq (1980-1988), which crushed the Iranian economy, women worked as nurses, medical professionals, and in administrative positions to support Iranian soldiers on the frontlines, often as volunteers. In the absence of men, many women also became the primary breadwinners for their families.[2]

More economic opportunities emerged for women during the late 1980s and 1990s, when President Hashemi Rafsanjani led efforts to revitalize the economy through expanding the role of the private sector. With the rise of both living standards and costs during this period, Iranian women actively sought more opportunities for obtaining education, including at the university level, while taking advantage of the family planning program from 1989 to access reproductive health care services and contraceptives.[3]

The 1997-2005 presidency of Mohamad Khatami, who campaigned on promises of gender equality and greater social and political freedoms, is commonly referred to as the “reform era.” Khatami’s administration sought to create an environment that facilitated greater civil society activities, expanded freedom of the press marginally, instituted modest political reforms, and aided women in entering the public sphere. The greater presence of women in civil society resulted in the establishment of the “One Million Signatures Campaign,” a grassroots effort aimed at raising awareness among the public through face-to-face discussions and the collection of signatures in a petition to change discriminatory laws against women. [4],[5] While the campaign played a role in mainstreaming the conversation about these discriminatory provisions, it did not succeed in achieving its broader goals, and several of its most active members faced prosecution.

Under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s two terms as president from 2005-2013, the modest political and social reforms of Khatami’s era, including women’s rights, came under sustained government assault. Among other discriminatory policies, Ahmadinejad implemented controversial “gender-rationing” restrictions at the university level, which limited women’s access to certain majors. In 2012, at least 77 fields of study in 36 different universities did not accept female students.[6] The final years of his administration also coincided with a shift in the country’s population planning, with an aim to increase population growth. During this period, several pieces of legislation were introduced to the parliament that further marginalized women in the job market.

Changing Views of Women’s Role in Iran’s Development Plans

The leadership of the Islamic Republic of Iran has never endorsed the concept of “gender equality,” instead considering it one of the greatest mistakes in western ideology.[7] Yet the government’s own development policies related to women’s role in society have continued to fluctuate over time, caught up in Iran’s enduring factional struggle between conservatives and reformists. In 1991, under President Rafsanjani, the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution established the Office of Women Affairs focused on women’s empowerment. Once President Khatami came to power, he changed the office’s name in 1998 to the Center for Women’s Participation, reflecting the more inclusive policies of his administration. More importantly he granted a separate budget for the center and included the center’s head as a member of his cabinet. Then in 2005, President Ahmadinejad renamed the center the “Center for Women and Family Affairs.” This change reflected his policies towards women in Iran, which emphasized their primary role as raising children and adhering to the authorities’ enforced norms of “pious” Islamic dress and behavior. In 2013, president Ahmadinejad also elevated the status of the center by transferring it into the Office of the Vice Presidency.[8]

The evolving view among officials has also influenced how the government has prioritized women’s issues in the economic development report it releases every five years. This plan, known as the “Five-Year Development Plan of the Islamic Republic of Iran” establishes the government’s macroeconomic priorities and is prepared by the executive branch and approved by the Iranian parliament (majles). It was notable that in the third development plan (2000-2004) prepared under President Khatami, the Center for Women’s Participation was directed for the first time to cooperate with other government agencies to facilitate the presence of women in public life.[9] The plan also included orders to assess women’s educational and athletic needs, increasing women’s employment opportunities, and improving injustices women faced in the legal system.

Before Khatami left the presidency in 2005, he prepared the fourth development plan (2004-2008), which emphasized empowering women in society while identifying legal barriers, such as women’s lack of protection from violence and strengthening civil society empowerment as the areas the government should focus on.[10] Despite some modest achievements, such as conducting research on the prevalence of domestic violence against women in the country, the government failed to change discriminatory legal provisions or to tackle the lack of sufficient legal protections related to violence against women. While the Ahmadinejad administration brought with it major policy shifts regarding women, his administration never finalized drafting the comprehensive women and family plan that was envisioned in the fifth development plan. The sixth development plan, drafted under President Rouhani and currently under the consideration of the parliament, proposes that the executive branch incorporate “gender justice” into its planning. In the draft the term “gender justice” is used to suggest not that women and men should have equal rights, but that their rights should correspond to their “appropriate” roles and needs under sharia law.

Women in the Workforce: A Current Snapshot

Iran’s official statistics display a complex reality three decades after the Islamic Revolution promised to bring women their human rights.[11] Women’s rights on some issues, such as the rights to education and health, have undoubtedly improved. The female literacy rate increased from 35.1 percent in 1977, to 80.2 percent in 2006, with the gap between male and female literacy decreasing from 23.5 percent to 8.5 percent.[12] Over the past 38 years, women’s enrollment in universities also increased to the point that, in 2009, women became the majority – more than 60 percent – of accepted students at the bachelor’s level. After being elected in 2013, President Rouhani’s administration reversed some of the discriminatory “gender-rationing” policies enacted under President Ahmadinejad, although interviewees reported to Human Rights Watch that some quotas remain in place for certain majors in a number of universities, restricting women’s access to fields of studies in those places.[13]

Over the past nine years, the economic situation of Iran has deteriorated, reducing Iran’s economic growth from around 6.7 percent in 2008 to -5.8 percent in 2013.[14] In line with the country’s worsening economic situation, government statistics showed a decline in economic participation and a rise in unemployment, a trend that widened the gap between male and female employment.[15]

The statistics illustrate a far bleaker situation for women in Iran who are seeking to translate these improvements in health and education into similar gains in the labor market. According to the World Bank, Iran is an upper-middle income country – bolstered by a large hydrocarbon sector – that is the second largest economy in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) after Saudi Arabia.[16] Yet women’s participation in the job market remains as low as 16 percent, significantly lower than the average participation in upper-middle income countries (69 percent) and lower than the average for all women in MENA countries, which is the lowest globally at 20.7 percent.[17] The 2015 Global Gender Gap report produced by the World Economic Forum ranks Iran among the last five countries (141 out of 145) in terms of gender equality, including equality in economic participation and opportunity.[18]

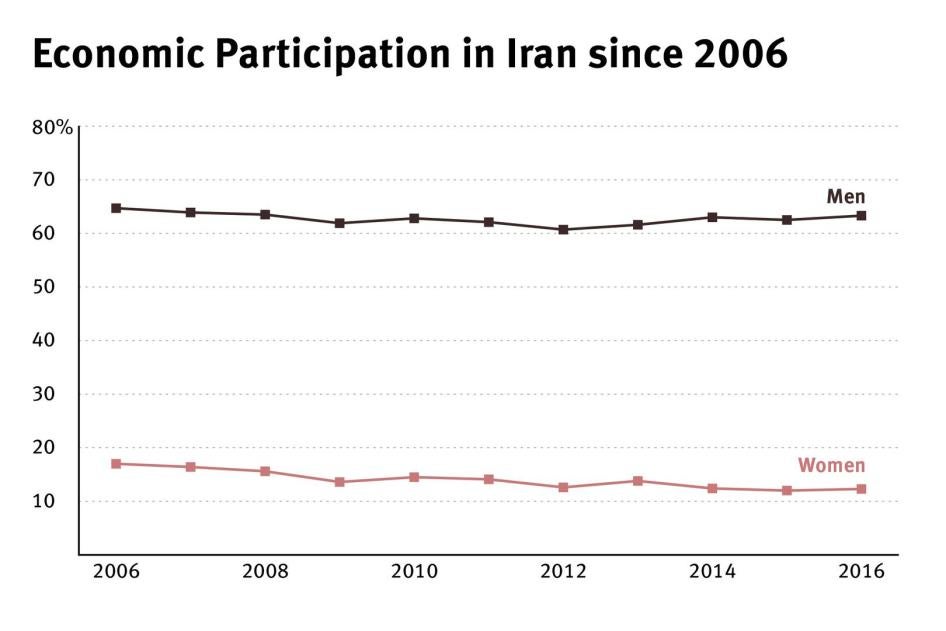

According to official statistics produced by the Statistical Center of Iran, in 2014, women constituted only approximately 16.6 percent of Iran’s workforce.[19] In the period between March 2015 and March 2016, only 12.3 percent of women participated in the country’s workforce, while the percentage of men who participated was much higher, at 63.3 percent. This is a stark gender gap, which has grown since Ahmadinejad’s election in 2005 over the past dozen years despite women’s increasing education levels.

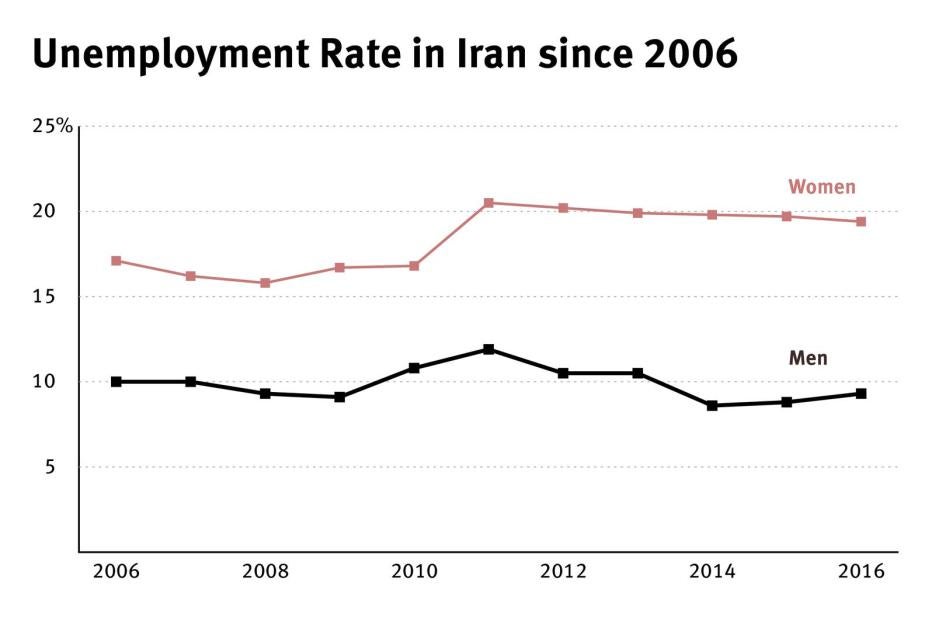

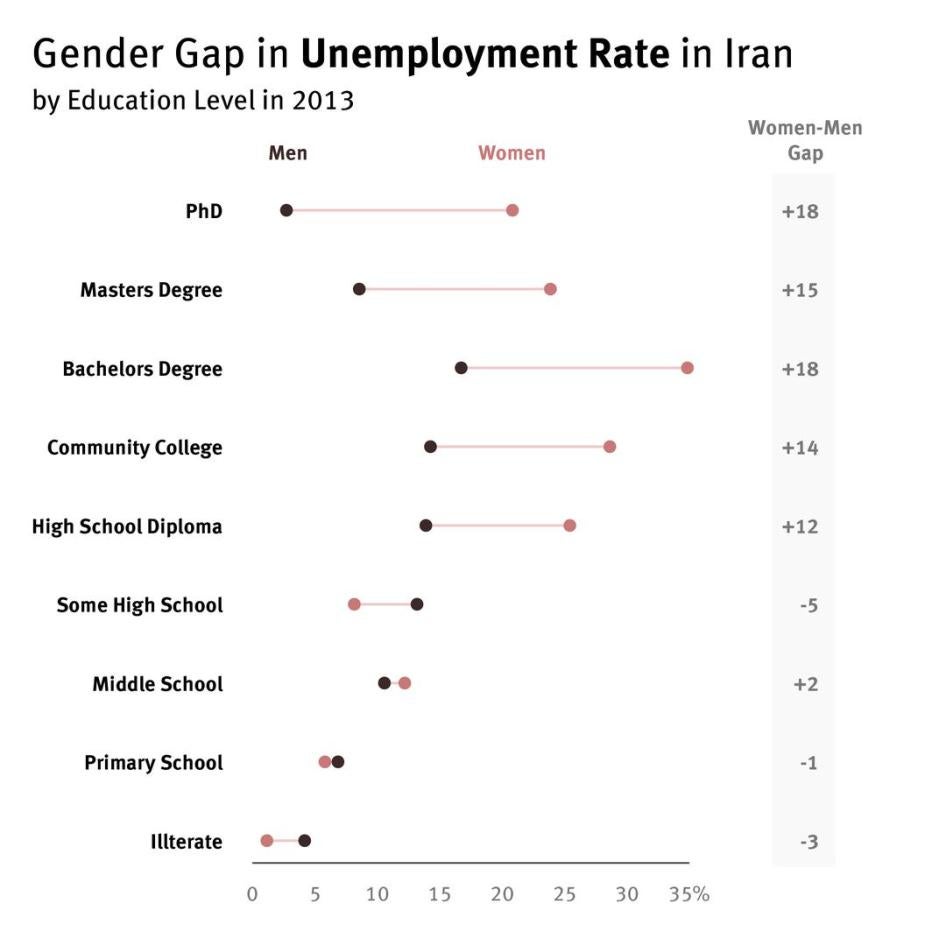

The economic crisis that began in 2008 lowered employment rates across the board. Yet while men’s participation rate in the labor market has almost returned to 2005 levels of 64.7 percent, women’s participation rates are still 27.6 percent lower than in 2005. This also remains true for female unemployment, which peaked at 20.5 percent in 2011 and remains at 19.4 percent (13.5 percent higher than in 2005).

And despite the fact that the number of working women with higher educational degrees increased from 860,000 in 2005 to 1.5 million in 2015 (a 67.5 percent increase), unemployment among this group are one of the highest in the country.[20] The 2011 national census data also shows that 48.15 percent of unemployed women have received higher education.[21]

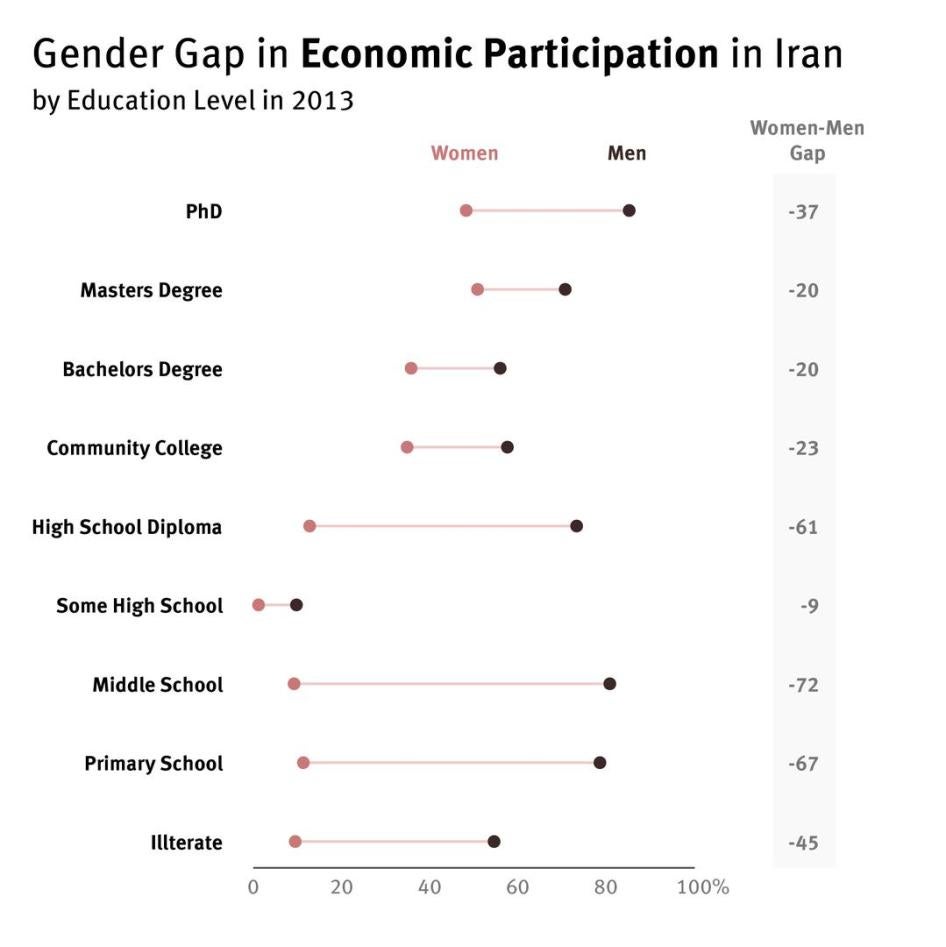

The data also shows a narrower gap than national average of economic particiation between male and female economic participation among individuals with higher education levels. While this shows women with higher education are more eager to participate in the economy, they find it more difficult than men to get jobs that suit their qualifications.

Women only constitute 14 percent of the private sector’s workforce while this number is 22 percent in public sector.[22]

Since 2005, the Iranian government has started operationalizing plans to transfer government-owned companies to the private sector.[23] While the disparities between male and female employment in both public and private sectors are clear, the gap between male and female employment is larger in the private sector than the public sector. Unless the gender distribution of jobs in the private sector becomes more balanced, the country’s plan to privatize large parts of the economy could increase the overall gap between male and female employment.

With the nuclear agreement in place, many Iranians are optimistic that the removal of relevant economic sanctions will improve their difficult living conditions.[24] However, unless the government is willing to take measures to address the systemic discrimination against women, their economic situation is not going to improve significantly. Some government reports predict that even if the country can achieve the optimistic growth rate of eight percent predicted in the government’s five-year development plan, where about 310,000 jobs will be created, women’s economic participation will only increase to 19 percent, and their unemployment rate will remain at 20 percent.[25]

Women in the “Informal” and “Fragile” Economy

The majority of working women in Iran work in what is known as the “informal” economy. “Informal work” is broadly defined as working in units with minimal labor law regulations and oversight.[26] Women occupying such positions, mostly in the industrial and agricultural sectors, are particularly vulnerable to abuse since they do not receive protection from the labor laws.

A study conducted by the Office of the Vice President for Women and Family Affairs estimates that half of the jobs held by woman are in the “informal” economy.[27] In recent years, the government has prioritized improving conditions both for those women who are breadwinners for their households and for women who remain at home as “housewives” through a range of measures, such as the provision of health care.[28] Those measures have yet to materialize.

The number of women in the informal economy will likely increase due to undocumented refugees who are not included in the formal economy. In 2015, the Ministry of the Interior estimated that there is a total of 2.5 million Afghan refugees in Iran.[29] One and a half million of them have temporary resident permits, which allow them to work only in certain occupations, mostly in jobs that involve heavy or hazardous manual labor.[30] Examples include: plaster manufacture, making acid for batteries, digging, brick-making, laying asphalt and concrete, herding sheep, slaughtering animals, burning garbage, loading and unloading trucks, stone cutting, road building, mining, and farming.[31] These occupations are male dominant in Iran and are often not only poorly paid, but also are dangerous. These restrictions on access to the labor market for Afghan refugees effectively excludes Afghan women from the formal job market and pushes them towards work in the informal economy.

Over the years, employers have increasingly preferred to sign temporary short-term contracts which grants them more freedom to terminate the contract and reduces costs.[32] According to some labor rights activists more than 80 percent of Iran’s labor force is employed on the basis of temporary contracts.[33]

Small workshops with fewer than 10 employees are exempted from labor law protections and often use short term contracts to reduce costs. There are no publically available statistics on the number of workers, including women, who work in these small workshops. The study conducted by the Office of the Vice President for Women and Family Affairs states that most of these small workshops hire women with contracts from three to six months and considers the lack of job security for these workers a “serious issue.”[34] Some labor activists also believe that women are the primary victims of harsh working conditions in these workshops, working up to 12 hours a day without receiving benefits.[35]

UN bodies have recognized that “women are often overrepresented in the informal economy, for example, as casual workers, home workers or own-account workers, which in turn exacerbates inequalities in areas such as remuneration, health and safety, rest, leisure and paid leave.”[36]

Women in Senior Government Positions

Women have a limited presence at senior decision-making levels in the country. Under Iranian law, candidates for the presidency must be what the constitution refers to as “Rajol-E-Siasi” (رجل سیاسی), i.e., “political men.” There is disagreement among officials about the meaning of the word "Rajol" (commonly translated as “man”). Referring to negotiations during the drafting of the constitution, many argue that the phrase as a whole could be understood as “political persons,” without a specification as to gender.[37]

Despite this ambiguity on women’s participation, the Guardian Council, a body of Islamic jurists responsible for vetting candidates for elections, has never approved a woman to stand in presidential elections or elections to the Assembly of Experts despite women registering for both.[38] Similarly, no woman has ever served on the important Guardian Council or Expediency Council. For the 2016 election, the Guardian Council invited eight female candidates to participate in a test to determine whether they were qualified to run for the Assembly of Experts, although none qualified.[39] The Guardian Council did not approve any of the female candidates who registered for the 2017 Presdential elections, including Azam Taleghani, a former parliamentarian.[40]

There are currently no female ministers in the cabinet, although President Rouhani has appointed three women as part of his cabinet administration.[41] The minister of the interior, who holds the power to appoint provincial governors, has only selected men. However, the administration appointed at least three female county governors out of 430 positions across the country.[42] The administration has also appointed women to 13 out of 1,058 district governors, mostly in small provinces across the country.[43] In the past three years, there has been an increasing trend of appointing women as city and country governors and mayors across the country. On November 8, 2015, Iran appointed Marzieh Afkham as the ambassador to Malaysia. She became the first female ambassador since the 1979 revolution.[44]

Women cannot serve as judges issuing rulings, but they can be appointed as assistant judges and clerks. On September 21, 2016, Tehran’s general prosecutor appointed for the first time two women as investigators (investigating magistrates) in the juvenile court of Tehran.[45] In September 2015, Hojjatoleslam Alireza Amini, the judiciary’s human resources director, told Iranian media in a press conference that about 700 women are currently employed as assistant judges and clerks by the judiciary. According to Amini, the total number of judges in Iran is about 10,000.[46]

The number of women that occupy elected seats has marginally increased over time. Women currently occupy only 5.8 percent (17 out of 290) of parliamentary seats in the new parliament, but this is still the highest percentage since the 1979 revolution. The percentage of female candidates who registered for the February 2016 election also increased to 12 percent from 8 percent in 2012.[47] The number of women elected in city and village councils increased from 1,491 in 2006, to 6,092 in 2013.[48] In 2017’s city and village councils elections, women constituted 6.3 percent of candidates who registered in the race.[49]

II. Iran’s International Legal Obligations

Discrimination on the grounds of gender is prohibited under international human rights law. As a party to the International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) since 1976, Iran is obligated to “ensure the equal right of men and women” as set out in the Covenant, including the right to work.[50] The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), the body that interprets the Covenant, considers the right to work to include prohibitions on “denying or limiting equal access to decent work for all persons.” The Committee has also made clear that states are obliged to take “measures to combat discrimination and to promote equal access and opportunities.”[51] The Committee emphasizes in particular that pregnancies must not constitute an obstacle to employment for women and should not constitute a justification for loss of employment.[52]

The Committee has explained the meaning of prohibited discrimination as including direct and indirect discrimination. Indirect discrimination “refers to laws, policies or practices which appear neutral at face value, but have a disproportionate impact on the exercise of Covenant rights as distinguished by prohibited grounds of discrimination.”[53]

The ICESCR also includes special protections for mothers during a “reasonable period” before and after childbirth, including paid leave or leave with adequate social security benefits, the right to social security and social insurance, and the right to equal access to social services.[54] The Committee has made it clear that implementing the right to equal social security “requires, inter alia, equalizing the compulsory retirement age for both men and women; ensuring that women receive the equal benefit of public and private pension schemes; and guaranteeing adequate maternity leave for women, paternity leave for men, and parental leave for both men and women.”[55]

Iran has ratified five out of eight of the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) fundamental conventions, including the 1958 C111 Convention Concerning Discrimination in Respect of Employment and Occupation and the 1951 C100 Equal Remuneration Convention.[56] The observation made in 2013 by the ILO Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR), which examines the application of ILO conventions by state parties, emphasized that the Iranian Labor Code does not sufficiently meet the principle of “equal renumeration for men and women for work of equal value” in the Convention and urged Iran to take the opportunity of the review of the Labor Code to give full expression to this principle.[57]

Several provisions in the ILO conventions concerning maternity protection seek to ensure that women have non-hazardous employment options during and after pregnancy, without denying women the choice of continuing to perform their usual work. However, those conventions are not currently in force in Iran. According to article 2 of Convention No. 111, “[a]ny distinction, exclusion or preference in respect of a particular job based on the inherent requirements thereof shall not be deemed to be discrimination.” The CEACR however, has urged that exceptions to the rule of nondiscrimination be interpreted strictly to avoid “undue limitation of the protection which the Convention [No. 111] is intended to provide.”[58]

Under international human rights law, discrimination is not always intentional. Supposedly neutral laws, regulations, policies, and practices can have a discriminatory impact. The CEACR has stated that indirect discrimination within the meaning of Convention No. 111 includes discrimination based on “archaic and stereotyped concepts with regard to [the] respective roles of men and women… which differ according to country, culture, and customs [and which] are at the origin of types of discrimination based on sex.”[59] “Facially neutral” labor laws or social legislation and policies that have a disproportionate impact on women are forms of indirect discrimination.

Iran is yet to ratify the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the key international instrument to ensure full equal protections for women.[60] Following arduous years of debate and campaigning, the Iranian parliament passed the bill to join CEDAW in May 2003.[61] Conservative figures in the government however rallied to push the Guardian Council to reject the bill.[62] The bill has been with the Assembly of Experts, a body that rules over disputes between the Guardian Council and the Parliament, ever since.

III. Discrimination Against Women in Iranian Law

Iran’s 1979 constitution, its long-standing civil code, and the labor code are the core legal provisions that govern women’s role in the labor market. In addition to these laws and regulations, the ideology of the Islamic Republic shapes the country’s macro socioeconomic planning in areas such as population growth and defines official interpretations of “morality” and “modesty.” This ideological worldview translates into policies that disproportionately impact women’s lives and their access to equal economic opportunities. The 1979 Iranian constitution makes expansive promises to Iran’s citizenry, guaranteeing equal protection of the law and enjoyment of “all human, political, economic, social, and cultural rights, in conformity with Islamic criteria,” for both men and women.[63] The constitution also emphasizes the responsibility of the government to ensure both a “favorable environment for the growth of a woman's personality and the restoration of her rights, both material and intellectual.”[64] It also guarantees the “protection of mothers, particularly during pregnancy.”[65] Yet in practice the Iranian legal system emphasizes women’s role as mothers and spouses over other rights stipulated in the constitution, and relies on discriminatory laws codified in provisions of the civil code that defines spouses’ rights and responsibilities toward each other. The Guardian Council, the body that is responsible for interpreting the constitution, is controlled by conservative forces that often act to prevent greater legislative change towards gender equality.

Iran’s Civil Code and its Historical Development

The majority of the civil code provisions currently enforced in Iran, particularly the discriminatory provisions stipulating the rights of spouses, were drafted long before the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The 1936 Civil Code that codified personal status laws for the first time granted men an unrestricted right to divorce their wives outside the court system, defined the husband as the head of household, giving him the privilege to choose the family’s place of living, and selected a minimum age of marriage of 15 for girls and 18 for boys.[66] Under the law, a husband could prohibit his wife from obtaining an occupation he deemed against family values or harmful to his or her reputation.

Until 1968, these marriage and divorce-related matters were adjudicated in the ordinary civil court system. In 1967, the parliament passed the first family law, creating family courts and making divorce possible with only a court order and after proof that reconciliation is not possible.[67] The 1967 law was adopted based on the same principle in Iran’s 1936 civil code that defined the husband as the head of household and envisioned similar privileges for men. The parliament approved another round of amendments to the family law in 1976. New amendments included provisions that improved the rights of women in certain areas, such as by increasing the minimum age of marriage to 18. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, however, the 1967 family law was one of the first laws to be nullified. Until 2007, the articles of the old 1936 civil code were used in courts.[68] In 2007, a new family law granted jurisdiction over family disputes in the civil code to family courts. The current version of the civil code still includes discriminatory provisions that define the husband as the head of household, which gives him the power to choose the family’s place of living and allows him to prohibit his wife from obtaining an occupation he deems against family values or harmful to his or her reputation with a court order.

Labor Code

While the labor code includes provisions against forced labor and discrimination against women, it falls short of granting equal benefits to women and ensuring nondiscrimination through legal penalties and active enforcement. Article six of the Iranian labor law prohibits forced labor and states that “all individuals, men and women, are entitled to equal protection of the law and can choose any profession they desire as long as it is not against Islamic values, public interest, or the rights of others.”[69] Article 38 of the law also emphasizes that equal wages are to be paid to men and women performing work of equal value in a workplace under the same conditions.[70]

However, the labor code prohibits employers from hiring women to “perform dangerous, arduous or harmful work or to carry, manually and without mechanical means, loads heavier than the authorized maximum.” In July 1992, the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution ratified the “employment policies for women in the Islamic Republic of Iran.” Article five of the employment policies emphasize that the executive offices of the state should facilitate women’s employment, but in part this role is to ensure that there are enough women in jobs that are either encouraged by the authorities’ interpretation of Sharia as being suitable for women (specifically mentioned in the law as e.g., nurse, teacher, doctor) or jobs that are “mentally and physically suitable for women” (i.e. laboratory sciences, electrical engineering, social work, pharmaceutical sciences, and translating). Under the law, women seeking jobs for which there is no difference between being a man or a woman should be able to access them without discrimination. But Article 5 also designates certain professions, such as judges or firefighters, as not suitable for women either because of the authorities’ interpretation of Sharia on the matter or because of their claims that work conditions are unsuitable for women.[71]

The Iranian labor code also suffers from two additional shortcomings that lead to violations. First, the nondiscrimination principles in the the labor code do not cover the hiring process, which is critical for women to enter the workforce, particularly in higher paying, technical, or more senior positions. Second, as will be shown in the section on discrimination, there is a failure to enforce these nondiscrimination protections for women in the workplace.

Violations of the Right to Work

I am a woman who has invested so much time on education and can’t imagine myself without my profession. By pressuring me to leave my job, my husband wants to take away part of my identity.

—Shahnaz, lawyer and university lecturer from Tehran

Discrimination in the Right to Choose a Profession

In accordance with Article 1117 of the civil code, a husband can bar his wife from occupations he “deems against family values or inimical to his or her reputation.”[72] In practice, in order to ban his wife from a certain profession, a husband must file a case in court and provide justification to a judge. In 2014, the ILO expert committee, CEACR, urged the Iranian government “to take steps to repeal or amend section 1117 of the Civil Code to ensure that women have the right, in law and practice, to pursue freely any job or profession of their own choosing.”[73] Women interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report repeatedly noted that their right to choose their desired profession is restricted by Iran’s civil code, which is a violation of right to work under ICESCR.

Shahnaz, a lawyer and university lecturer who studied and worked before getting married, recounted that “because of my visual impairment, my husband did not think it was safe for me to teach at university in different cities, and took the case to court… We were married for two years. We had disagreements on several issues but he did not want me to work and did everything in his power to stop me from doing that.”[74]

The civil code provisions not only directly discriminates against women, but also facilitates discrimination by employers against married or engaged women. Iranian law does not prohibit employers from requiring a husband’s permission for a woman to work. “In our company, married women have to provide their husbands’ written consent, otherwise they won’t be hired. I was engaged at the time and had to present a form showing my fiancé had consented to me working,” said Sahar, a 26-year-old woman who works as a sales representative in a private company in Tehran. [75]

Several lawyers told Human Rights Watch that marital disputes over the profession of the wife are regularly used against women in family courts. While these disputes rarely make it to court as a separate claim, a problem with the wife’s profession is often part of a husband’s claim for or against divorce and can become one of most contentious issues.

Marzieh, a lawyer from Tehran who has represented several women and men in family disputes note: “My male clients commonly use the phrase ‘since she started working’ when they are complaining about their wives’ behavior. Many of them comfortably pass judgments on different occupations [they consider unsuitable for their wives].”[76] Marzieh added: “For example, many don’t like that their wives work in beauty salons, as [they] do not consider that a dignified job.”[77]

“Two years ago, I had a client who was going through a rough time in her marriage,” said Negar, a lawyer who practices in Khorasan province. [78] “She was a medical professional and had to work one or two night shifts every week. When things turned sour, her husband complained to the court that he did not think it was suitable for his wife to spend the night out, and the judge ruled in his favor and asked my client to either change her working conditions or give up her job entirely.”[79]

Lack of Equal Access to Social Security Benefits

Iranian social security regulations discriminate against women for certain benefits, such as family bonuses, and instead favor payment to married men with children. In order for a woman to be eligible to receive such monetary compensation, she must prove that her husband is unemployed or has a disability or that she is the sole guardian of their children.[80] Iranian social security rules also discriminate against women’s families when the woman is not the primary breadwinner. Article 148 of the labor code obliges employers to insure their workers under the Social Security Act, and the family of the insured can also receive health insurance from the social security organization.[81] However, because Iranian law considers the man the head of the household, the family of a female employee can only benefit from her health insurance when she provides for him or when her husband is unemployed or disabled.[82] This discrimination concerning benefits even extends to what families receive after female or male members die. After paying a social security tax and satisfying certain age and work experience requirements, a family member of a social security beneficiary is entitled to a portion of these pensions after they die. However, while a man’s spouse and children under the age of 18 can receive a portion of his pension, when an insured female dies, her family is not entitled to the same benefits.[83] Women who spoke to Human Rights Watch expressed dissatisfaction about Iranian law’s discriminatory social security benefits. “My husband and I both worked in the same field and in similar positions. There were times that I held a more senior position and earned more than him,” explained Narges, a retired financial manager in Tehran. [84] “But although I have paid the exact same portion of my social security as my husband for my entire professional life, if I die I can’t leave anything for him but if he dies, I can get his salary.”

Violations of the Freedom of Movement

According to Article 18 of Iran’s passport law, married women, including those under the age of 18, must receive permission from their husbands to get a passport. While the permission to travel abroad can be included in the marriage contract, a husband’s written consent must be presented along with a passport application.[85] Even if a husband grants permission to his wife when she is applying for a passport, he can always change his mind and prevent her from traveling abroad. This legal provision allows men to prevent their wives from traveling for any reason and at any point in time. In an emergency situation, however, the prosecutor can grant permission for women to travel without such permission. In March 2012, President Ahmadinejad’s Administration proposed an amendment to the passport law that would restrict freedom to travel outside the country for unmarried women as well. According to the proposed amendment, women below the age of 40 would require permission from their legal guardian, or “Sharia ruler,” to obtain a passport to travel abroad.[86]

Article 12 of the International Covenent on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Iran is state party, protects the right to free movement, including the right of everyone to leave any country, including their own.[87] The Human Rights Committee – which oversees states’ compliance with the ICCPR – considers freedom of movement to be “an indispensable condition for the free development of a person” that is violated if the restrictions “make distinctions of any kind, such as on the basis of race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.” The Committee has on several occasions found that measures preventing women from moving freely or from leaving the country by requiring them to have the consent or the escort of a male person constitute a violation of right to freedom of movement. In 2011, the Committee specified in its concluding observations that Iran should amend its laws to remove the requirement for a husband’s approval when a woman intends to leave the country.[88]

In September 2015, Iranian media reported that the husband of Niloufar Ardalan, the captain of Iran’s women’s futsal – five-a-side football – team, had refused to grant his wife permission to travel, effectively barring her from accompanying her team to participate in the Asian futsal tournament in Malaysia.[89] Ardalan told Iranian media that her husband refused to grant her permission to leave the country because he expected her to attend their child’s school orientation.[90] “This is the first time that the Asian Championship is happening and I have practiced and feel prepared, but my husband refused to give me my passport. Because of his position, I lost the chance to play in the championship,” Ardalan told Ghanoon, an Iranian daily newspaper.[91] She continued, “I wish the authorities would create provisions for female athletes so we can defend our rights in this situation. These matches were very important for me and I wanted to have a role in raising my country’s flag as a Muslim woman.” Following the reaction from civil society, the office of Tehran’s prosecutor granted her a one-time authorization to participate in matches that took place in Guatemala in November 2015.[92]

On May 8, 2017, ISNA news agency reported that Zahra Nemati, a member of Iran’s national paraolympic team, was banned from traveling abroad by her husband after she filed for divorce.[93] A day later, Tayebeh Siavashi, a member of the Cultural Commission of the Parliament, told ISNA that she was able to remove the travel ban after consulting with Iran’s Olympic Committee. “The country has invested in her and if she cannot travel abroad, it can damage our country’s reputation,” Siavashi added.[94]

A few companies’ hiring managers and employers told Human Rights Watch that they prefer not to hire women for jobs that require extensive travel. One employer told Human Rights Watch that he prefers not to hire women for jobs that require them to travel abroad because he cannot trust that they will receive permission from their spouses to travel in a timely fashion. Although no women interviewed stated that this issue was given as a reason they were not hired for a position, it may become an increasing problem as Iran’s economy reconnects to the global market after years of isolation that limited travel opportunities for both men and women professionals.

Shahindokht Mowlaverdy, the vice president for women and family affairs, told media on September 15 that her office will seek to amend the law requiring married women to receive permission from their husbands to travel. “Until the law is amended, we will look for exemptions so our female scholars and athletes can participate in international conferences and tournaments.”[95] However, Human Rights Watch is not currently aware of any proposed amendments.

IV. Lack of Legal Protection or Enforcement

Violations of the Right to Equal Access to Work

The standard recruitment process in the Iranian public and private sectors shows that employers regularly use gender as a qualification for jobs. Moreover, gender discrimination is not limited to allegedly “harmful” or “unsafe” jobs, from which women are excluded under Iranian law, but is also applied to employment for which there is no domestic legal basis for denying someone a position based on their gender, such as technical or managerial positions. Iranian law does not prohibit advertising gender as a qualification for a job. It appears that a number of employment opportunities in the public and private sectors specify gender preferences, and the majority of these job postings appear to do so without any stated justification.

When interviewing female jobseekers, Human Rights Watch learned of a construction project management company based in Tehran that only hired men for all positions. When Human Rights Watch asked about this discriminatory policy, one of the company’s employees recalled that the management of its parent company made the decision, following rumors that several male and female employees were involved in romantic relationships. “As [management] was unhappy about [alleged illicit] relationships within the company, they decided that eliminating women was the solution to their problem,” said Roozbeh, a junior manager in the company.[96]

Discrimination in Hiring Practices in the Private Sector

Human Rights Watch examined hundreds of job vacancies on different websites and in public newspapers, including jobs advertised on Iran Talent – one of the most popular job search websites for skilled labor in the private sector between May and September 2016. In numerous incidents, job advertisemetnts in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics stated explicit preferences for male candidates. In contrast, many of the postings directed at women were for assistants, secretaries, or other administrative workers. Jobs in business, such as in sales or marketing, were generally advertised for both males and females.

Out of the 66 open vacancies reviewed by Human Rights Watch that specified female as their preferred gender on September 19, 2016, only 12 of them could be categorized as “specialist” positions. The rest were administrative, including 19 vacancies for hiring secretaries. Out of the 176 vacancies posted on Hamshahri online (a popular job search site) on one day (September 20, 2016) for vacant secretarial positions, 173 explicitly stated a preference for women. In contrast, out of the 58 positions that explicitly stated a preference for men on Iran Talent on that same day, 55 were professional and technical positions.

Human Rights Watch’s analysis of job advertisements also indicates that some foreign companies and subsidiaries have followed similar discriminatory patterns. For example, a Swiss law firm stated a preference for hiring a female secretary in a local job advertisement, while a French telecommunications company stated a preference for a male regional project manager. When asked why he only advertises for female secretaries for his company, Ali, the CEO of an online advertising company, told Human Rights Watch that he thinks “having women as secretaries will create a gentler interface for his company.” He added: “It’s important for us to project that image to our client and outside contacts.”[97]

The experiences of women interviewed for this report suggest such discriminatory practices are widespread. Naghmeh, a 26-year-old woman from the city of Tehran, said, “I am a mechanical engineer and I was interviewed for a position in Iran's oil and gas fields in Asaluyeh port (where the Pars special economic energy zone is based). My contact in the company told me that they really liked me, but that they did not want to hire a woman to go to the field.”[98]

Pooria, a 30-year-old male civil engineer who worked on construction projects outside Tehran, stated there were no women on the construction sites he worked. While his company had three or four women who worked in the office, he told Human Rights Watch, “I don’t think the management was very eager to hire women. I think they felt that it would add ‘complications’ to the [work] environment.”[99]

The absence of a comprehensive legal framework in this area allows human resources teams to institute openly discriminatory hiring practices, a practice that can only be kept in check by individual initiatives or company policies. Nioosha, a human resources manager at one of Iran’s largest insurance companies, told Human Rights Watch that she attempted to ensure that positions are open to both genders in her own company. “Since there is no law prohibiting advertising gender [preferences], it is up to the manager to guarantee gender equality. Coming from [past] work with international organizations, I cared deeply about ensuring gender equality at the work place. It did not take long for the company to get used to having women managers as well as men.”[100]

Discrimination in Hiring Practices in the Public Sector

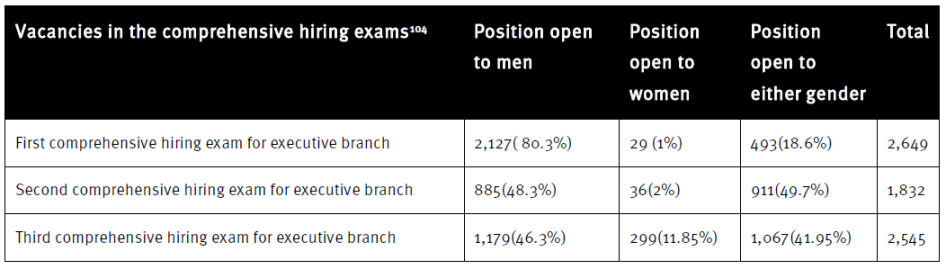

Thousands of public sector positions are filled through exams administered by a state evaluation administration, known in Farsi as the Sanjesh. In April 2015, the Rouhani administration consolidated entrance exams for several government agencies and began offering comprehensive exams for executive branch positions. Human Rights Watch analysed 7,026 advertised vacancies for the past three public service entrance exams. The result of this analysis was that in about 60 percent of vacancy advertisements reviewed by Human Rights Watch an explicit preference for a man was stated. The majority of managerial positions advertisements reviewed by Human Rights Watch were also exclusively limited to men with no justification. In the first exam that was offered in May 2015, more than 80 percent of the 2,649 announced vacancies were limited to men, with certain agencies, such as the state tax organization, earmarking 96 percent of its positions for men.

Human Rights Watch’s analysis shows that the distribution of jobs improved marginally in the second exam offered by the government in March 2016. However, in the third exam, out of 2,545 vacancies announced, more than 46 percent of them were restricted exclusively to men.

These discriminatory practices were first brought into the attention of the government by Shahindokht Mowlaverdy, vice president for women and family affairs in April 2015.[101] On July 31, 2016, President Rouhani postponed the exam to investigate apparent discrimination against women in the job market.[102] The move was welcomed by the women’s parliamentary faction.[103]

Discrimination in access to work has not been limited to hiring practices in the public sector. On July 9, 2014, the Pupils Association News Agency (PANA) published an image of the notes from a municipality of Tehran meeting that took place on May 11, 2014. The notes showed that the municipality required high-level and mid-level managers to hire only men as secretaries, typists, office managers, operators, etc.[105] On July 13, 2014, Farzad Khalafi, a press deputy at the Tehran Municipality’s media center, confirmed the existence of the notes in an interview with Iranian Labor News Agency (ILNA), claiming that jobs like administrative assistants and secretaries are “long and time-consuming,” and therefore the decision was made for “women’s comfort.”[106] On July 28, 2014, Iranian media published a letter the international affairs deputy at the Ministry of Labor had sent to the Tehran municipality asking the office to reverse the practice.[107] The letter specifically noted that the “requirements” in the written summary violated Iran’s anti-discrimination commitments under ILO conventions and constituted a violation of human rights.[108] In response to the letter, the municipality of Tehran denied ever having issued such an order, and accused the Ministry of Labor of parroting claims made by foreign media.[109] Discriminatory practices in public sector hiring are not limited to comprehensive exams for the executive branch. In the vacancies announced by the social security organization in 2015, out of a total of 1,435 positions, 618 were open exclusively to men, while just 151 were exclusively for women. The social security organization designated 566 positions open for both men and women. An analysis of vacancies in municipalities across the country reveals similar levels of discrimination against women in the public sector.

Discriminatory Hiring against Women for Managerial Positions and Promotions

Iranian women have to battle against societal stereotypes to work as managers and supervisors. While some managerial jobs have explicit gender preferences (usually preferring men), many women interviewed felt that their chances of getting hired or promoted as managers are even lower due to their gender. “I felt that in our family business, women have to try twice as hard to prove themselves when it came to supervisory roles. We expect women to demonstrate commitment and seriousness to a far greater degree than men,” said Soraya, a 29-year-old woman who helped manage a construction company in Qazvin. [110]

Several individuals, both employers and jobseekers, reiterated that women are considered less serious than men in the workforce. The perception that women are the primary caretakers and responsible for domestic chores makes them less attractive candidates for jobs that require unpredictable work hours and higher levels of responsibility. Several interviewees told Human Rights Watch that in their workplaces, single women are preferred to married ones because employers think they can commit to work longer hours. “I try to be flexible with my employees and understand their limits,” Ali, an Iranian CEO claimed. “But since women’s top priority is family stuff, I can’t leave my business in their hands.”[111]

Some female managers experienced difficulties in their work by male staff members. “As the managing director of the company, my mother had to go to several construction sites to negotiate deals with project managers, but [male] guards and random [male] laborers would prevent her from entering the sites,” Soraya recalls.[112] “She literally had to get around them to enter.”

A number of managers and employers told Human Rights Watch that companies are also less inclined to hire women for higher level positions that represent the organization externally because of the perception that the company might not be taken seriously. Fariba, who worked as the representative of an independent contractor of a municipality outside Tehran, recalled the pressure she endured because several public officials whom she interacted with in her profession did not want to deal with a woman. “I needed to go to the municipality for my project but the [male] manager I needed to talk to would simply refuse to take the meeting with me, and he would then call my boss saying that it is better if a man handles the project.”[113]

Many women told Human Rights Watch that they do not feel they have equal opportunities to be promoted in their employers’ companies. “I often impress my boss through points I raise about programming, but I rarely get the chance to participate in the decision-making process,” says Safoura, who works for consulting company in Tehran in a mid-level position.[114] “Once my boss told me to come and explain my points in a meeting, but then he immediately retracted his suggestion, saying that it’s not a good idea since it’s a men’s club.”

Maryam, who passed an exam to be hired at a bank in Tehran, feels that while her bosses judged her by her merits when they initially hired her, she no longer perceives an opportunity to grow in her role. “We are treated equally as low-level staff members, but when it comes to promotion, women are never promoted to managerial positions.”[115] Likewise, Shabnam, a journalist who covers social issues for an independent publication, says that in her field women rarely become editors or chief editors of newspapers.[116] Negar, another journalist who conducted research on women’s employment in her province, shared this belief, stating that that there are very few women on Iranian newspaper editorial boards, even for local publications.[117]

Violations of the Right to Equal Pay for Equal Work

Iranian law includes provisions on equal pay for equal work, but several reports indicate that in practice, women are paid less than men in the job market. Article 38 of the labor code stipulates that equal wages are to be paid to men and women performing work of equal value in a workplace under the same conditions, and Article 49 of the labor code requires that businesses that are bound by the labor code must define the classification category in which each job falls and report the salaries and benefits in accordance with that category.[118] Workplaces with more than 50 employees have to follow the protocol for job categorization.[119]

The 2016 Global Gender Gap report, however, estimates that women earn 41 percent less than men for equal work, and that men in general earn 5.79 times more than women.[120] According to the Iran Talent website’s 2015 annual salary report, prepared by surveying 36,000 participants, women earn 23 percent less than men. The income gap for managerial positions is higher, at 36 percent, and 28 percent for jobs categorized as “expert.” While there are no official statistics publically available about income disparities between men and women, several officials have acknowledged such disparity. Soheila Jelodarzadeh, a consultant to the minister of welfare and a former parliament member, told ILNA news agency on June 21, 2015 that “according to the law, male and female workers should receive equal salary but in practice, in many cases, employers pay their female workers as low as one third of the legal minimum wage.”[121]

Women and managers who worked for large companies in Iran told Human Rights Watch that the women employed there receive the same salaries as men. However, several of them said that when it comes to benefits (such as overtime and bonuses), men received better treatment. Niloufar, who worked for a public sector company in Tehran, told Human Rights Watch that she was paid less than her male coworkers when it came to benefits and overtime. “In theory, the baseline of our salaries is the same but in practice men earn more in their paycheck when you add benefits.”[122] Maryam, an accountant agreed, clarifying that, “You can significantly increase your income if you take on more hours, but overtime is limited to the men in the bank.”[123] The justification for this practice appears to be grounded in explicit biases male managers have about working women. Ali, a CEO of a small company, says the reason he prioritizes men for raises and benefits is that he understands that they have to pay for their families, unlike women “who get to keep the money [for their personal spending] if they want to.”[124]

“In my field, there is a clear salary difference between men and women when it comes to managerial positions,” said Niyayesh, a 35-year-old accountant who lives in Tehran. [125] “The discrimination is also very clear when it comes to social security benefits. Many employers refuse to provide health insurance [to women], with the justification that they don’t need it.”[126]

Lack of Protection from Sexual Harassment

The ILO and the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognize sexual harassment in the workplace as a form of discrimination. In its 1996 Special Survey on Convention No. 111, the ILO Expert Committee (CEACR) stated that “sexual harassment undermines equality at the workplace by calling into question individual integrity and the wellbeing of workers; it damages an enterprise by weakening the basis upon which work relationships are built and impairing productivity.”[127] The Committee further defined sexual harassment as: “[A]ny insult or inappropriate remark, joke, insinuation and comment on a person’s dress, physique, age, family situation, etc; a condescending or paternalistic attitude with sexual implications undermining dignity; any unwelcome invitation or request, implicit or explicit, whether or not accompanied by threats; any lascivious look or other gesture associated with sexuality; and any unnecessary physical contact such as touching, caresses, pinching or assault.”[128] The Committee has asked the Iranian government to explicitly define and prohibit all forms of sexual harassment, including both quid pro quo and hostile environment harassment at work.[129]

In 2016, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights stressed the need for legislation for sexual harassment stating that “All workers should be free from physical and mental harassment, including sexual harassment. Legislation, such as anti-discrimination laws, the Penal Code, and labor legislation should define harassment broadly, with explicit reference to sexual and other forms of harassment, such as on the basis of sex, disability, race, sexual orientation, gender identity, and intersex status. A specific definition of sexual harassment at the work place is appropriate and legislation should criminalize and punish sexual harassment as appropriate.”[130]

Several women reported different forms of sexual harassment – mainly verbal – in their workplaces, and interviewees, especially in the public sector, identified the security offices, which enforce the company’s “moral codes,” as the department that received complaints about harassment. However, because there is a social stigma attached to victims and a lack of trust in the security offices as an institution, women felt uncomfortable reporting complaints to their employer. They were often also unaware of the existing mechanisms and procedures for reporting such abuses. Employers and employees interviewed told Human Rights Watch that they were not aware of any anti-sexual harassment policies in their companies.

There is no reference to sexual harassment in Iranian law. However, “coerced” sexual intercourse (Zena-e-be-onf) with a woman is punishable by execution under Iran’s criminal code, and kissing and “love making,” if done by force, can also be brought before a court.[131] Although the Office of the Vice President for Women and Family Affairs is preparing to submit to the parliament a comprehensive bill to protect women from violence, Human Rights Watch was not able to identify any effort to prohibit harassment at places of work. [132]

Fariba remembers that in the public sector organization with which she worked closely, an employee was accused of raping his secretary. He was put on paid leave only because several people found out about it, she recalls. “The first thing was that the woman left the organization and everyone talked about her as if it was her fault. Eventually, when rumors spread and everyone started talking about it, the manager was put on leave but all the organization’s effort focused on sweeping things under the rug.”[133]

Setareh, who works as a sales representative, was disturbed when her manager told her and her coworker that they should take up a client on his offer for dinner after working hours. “My coworker clearly did not think it was appropriate to accept the client’s invitation for dinner after working hours, but our manager insisted that we should be open to meeting clients after hours saying nothing will happen to me if she hangs out in a restaurant after working hours with the guy,” Setareh explained. [134]

On Febuary 6, 2016, Sheena Shirani, a TV anchor with the state broadcaster, the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), released a voice recording of her boss asking her to engage in a sexual relationship with him. She told Human Rights Watch that during the eight years she worked in the organization, she reported several incidents of harassment to the security office at IRIB, but the response was always that she should change her behavior to avoid being harassed. Sheena said she did not leave during this time because her boss “has always helped me in the organization” and ultimately quit her job after he asked her to have sex with him.

Discrimination Based on Dress Code