Summary

Some things are getting better. There is electricity in the next village, and we may get electricity here, too. But none of that matters if our land is gone.

–Nu Yee, San Klo, Karen State, February 2015

The businessman takes the land from the farmer, but when the farmer protests, he becomes the criminal.

–Lawyer, Hpa-an, Karen State, August 2015

In Burma, where 70 percent of people earn a living through agriculture, securing land is often equivalent to securing a livelihood. But instead of creating conditions for sustainable development, recent Burmese governments have enacted abusive laws, enforced poorly conceived policies, and encouraged corrupt land administration officials that have promoted the displacement of small-scale farmers and rural villagers.

Conflicts over land have come to the forefront of Burma’s national agenda in recent years. These tensions have intensified as the country has embarked on a process of democratic transition and reform, with greater openness in some areas, but continued military dominance in other sectors, particularly where the military controls key government ministries.

Land disputes are a major national problem, with rising discontent over displacement for plantation agriculture, resource extraction, and infrastructure projects—often without adequate consultation, due process of law, or compensation for those displaced. In many parts of the country, those contesting land seizures have taken to the streets in frequent demonstrations but have faced retaliation in the courts.

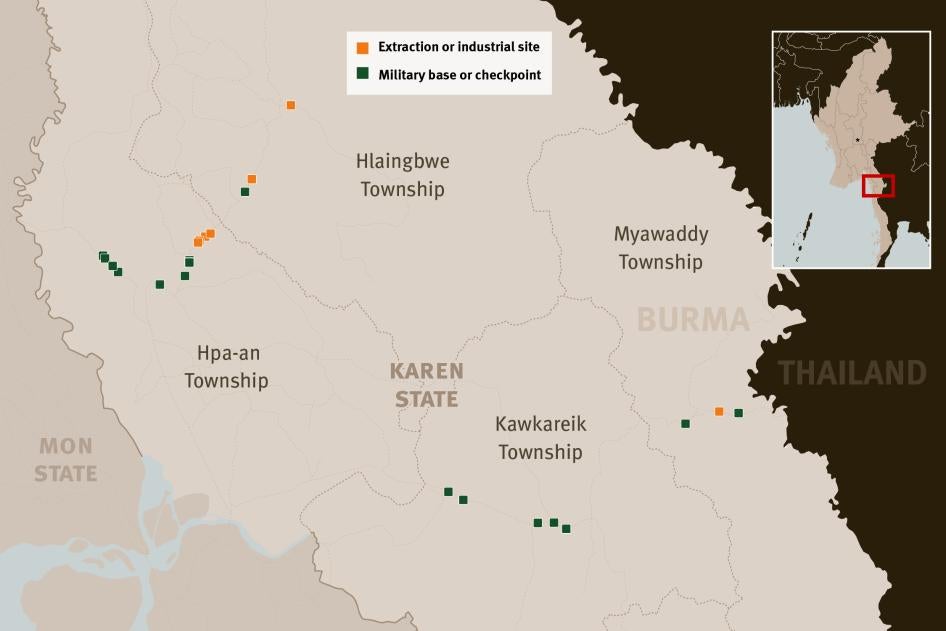

The dual problems of land confiscation and reprisals against protesters is particularly acute in Karen State. Located along the border with much more prosperous Thailand, Karen State is viewed by many as a desirable site for investment in the tourism, extractive, and agriculture industries.

The economic opening of the country to investors has made land more valuable, while the peace process in Karen State and other ethnic areas has given access to areas previously beyond the reach of the Burmese armed forces and military-linked businessmen. The result is that powerful interests are gaining land through questionable means while farmers are losing it, often without adequate compensation.

As peace negotiations continue and the return of refugees from Thailand gains credence, land tenure issues will likely intensify, particularly as those who return find that land they previously farmed has now been occupied by government or business interests.[1]

This report focuses on government abuses related to land confiscation in areas near Hpa-an, the capital of Karen State. The villages in this area are under the effective control of the Burmese military, called the Tatmadaw, and military-controlled militias called Border Guard Forces (BGFs), or are located in areas of mixed governance by the ethnic armed group Karen National Union (KNU) or other militias and the government.

The report illustrates the dynamics of land confiscation in Karen State—a longstanding problem previously documented by Human Rights Watch and local organizations such as the Karen Human Rights Group.[2] It details cases in which government officials, military personnel and agents on behalf of the army, local militia members, and businessmen have used intimidation and coercion to seize land and displace local people. It also documents the impact of land loss on local villagers, some of whom have farmed land for generations but lack legal documentation to prove it.

Human Rights Watch found that farmers who protest land-taking and try to stake a claim to their land face retaliation by police and government officials, and prosecution under peaceful assembly and criminal trespass laws. Many farmers whose land has been confiscated as far back as a decade have not been able to obtain any redress and, in some cases, continue to suffer abuses after calling for compensation or attempting to reclaim land. The government’s failure to provide adequate compensation or other redress for land confiscation means that victims struggle to make ends meet, and frequently must become migrant workers abroad or rely on relatives working in Thailand or elsewhere abroad for economic survival.

Villagers and local groups say that government land registration services are effectively inaccessible to them, and farmers assert that local government offices fail to uphold their rights against more powerful moneyed interests. In some cases, villagers allege that local government officials have acted as brokers for land deals or facilitated the granting of licenses for mining and other projects, leaving long-time residents and farmers empty-handed and without effective recourse.

Burma’s departing national government adopted a cabinet resolution to enact a National Land Use Policy in early 2016, which could form the basis of future land law reform. The new policy aims to improve land classification and land information management systems, recognize communal tenure systems and shifting cultivation practices, create more independent dispute resolution procedures, and provide restitution for victims of land confiscation or those who have been forced to abandon lands due to past or ongoing conflict.

In November 2015, the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD), led by Aung San Suu Kyi, swept nationwide elections. The party assumed executive power in March 2016 and appointed U Htin Kyaw as president. Since then the NLD government has made little progress on reforming land policy to advance these policy goals or otherwise ensure that rights are protected.

To address the problems facing farmers and other villagers such as those detailed in this report, the government should adopt additional safeguards (see Section IV). Crucial is tackling the significant gap between government documentation of land rights and the manner in which land is actually being used or occupied, and by whom, in rural communities. Measures to be adopted should include recognizing community land tenure systems and shifting cultivation systems, providing formal documentation to farmers and villagers recording existing land use, and ensuring that villagers can challenge government decisions about land in an independent forum or body with the power to adjudicate land disputes.

In addition, the government should enact administrative changes to ensure that land reform at the national level results in actual changes at the local level, including by providing genuine notice to farmers where proposed land use changes would affect their livelihoods, and by implementing robust public consultation procedures. The government should also end the arbitrary arrest and detention of land activists for engaging in peaceful activities to protest land seizures.

A special taskforce consisting of the Burmese Defense Services (Tatmadaw), the Justice Ministry, and the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission should investigate all alleged abuses by Border Guard Forces (BGF) connected to land confiscation in BGF-controlled areas, make public the findings of the investigation, and ensure the return of land taken improperly by members of the BGF to the villagers and farmers who had previously been using it.

Methodology

From January to August 2015, Human Rights Watch conducted interviews in Burma with ethnic Karen farmers, laborers, and other villagers from 27 different villages in Hpa-an township and Hlaingbwe township, Karen State. Some villages were visited multiple times. In April 2015, Human Rights Watch also interviewed Karen migrant workers in Mae Sot and Bangkok, Thailand.

Altogether, Human Rights Watch interviewed 72 farmers and laborers, 48 men and 24 women. Interviews were conducted in Po Karen, Sgaw Karen, and Burmese with the help of interpreters, and in English. Local groups working on land rights helped identify individuals to interview. Human Rights Watch also conducted interviews with people displaced during fighting in October 2014. Migrant workers in Thailand were referred to Human Rights Watch by family members in Burma.

All participants were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the data would be collected and used. All orally consented to be interviewed. The names and other identifying details of some interviewees and villages have been withheld or changed to prevent possible reprisals.

Most interviews were conducted in villagers’ homes with between one to four people interviewed. Often the interviews included other members of the village, some of whom participated in the interviews.

A number of villagers expressed concerns about security and possible retaliation if they spoke with Human Rights Watch in their villages. In such instances, Human Rights Watch reimbursed villagers for travel expenses to meet in a secure location.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed and obtained information from land experts, former government officials, nongovernmental organization workers, and local community members.

Human Rights Watch sought information from the national government and the Karen State government relating to land confiscation in Karen State and in Burma more generally. A Human Rights Watch representative met with the vice chair of the Hpa-an Special Industrial Zone in August 2015 in Hpa-an, and officials from the national Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation in Burma’s capital, Naypyidaw, in February 2016.

In October 2015, Human Rights Watch received a letter from the office of the chief minister of Karen State in response to our letter seeking information on alleged human rights abuses related to land confiscation.

Throughout the research, Human Rights Watch collected copies of land use certificates, tax receipts, letters to government officials and responses received, land registers prepared by villages, and site maps. We visited almost all of the sites of land confiscation discussed in this report.

Because of government-imposed travel restrictions and security concerns at the time of the research, Human Rights Watch was unable to conduct interviews in areas under the control of the Karen National Union (KNU), the main ethnic Karen political organization, whose armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), has waged a war against central government control since 1948. As a result, this report does not document abuses that may be occurring in KNU-controlled areas.

Glossary

|

ADB |

Asian Development Bank |

|

ASEAN |

Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

|

BGF |

Border Guard Force |

|

CCVFV |

Central Committee for the Management of Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands |

|

CEDAW |

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women |

|

DKBA |

Democratic Karen Benevolent Army |

|

ESIA |

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment |

|

FAB |

Farmland Administration Body |

|

FPIC |

Free, Prior and Informed Consent |

|

GAD |

General Administration Department |

|

GMS |

Greater Mekong Sub-region |

|

ICCPR |

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights |

|

ICESCR |

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights |

|

IDP |

Internally Displaced Person |

|

JICA |

Japan International Cooperation Agency |

|

KNLA |

Karen National Liberation Army |

|

KNU |

Karen National Union |

|

LUC |

Land Use Certificate |

|

MoECaF |

Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry |

|

MNREC |

Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation |

|

SIZ |

Special Industrial Zone |

|

SLORC |

State Law and Order Restoration Council |

|

SLRD |

Settlement and Land Records Department |

|

SPDC |

State Peace and Development Council |

Terminology

In this report Human Rights Watch uses the terms “Burma” in reference to the country and “Burmese” for the population generally, regardless of specific ethnicity. “Karen” is used in reference to the state and its predominant ethnic group. The Burmese government refers to the country as “Myanmar” and the state and ethnic group as “Kayin,” reflecting changes to the English translations of names made by the military State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) after it seized power in 1989. All of these terms are still commonly used inside Burma. The 2008 constitution also changed the administrative areas called “Divisions” to “Regions,” so for example Pegu Division became Pegu Region after March 2011 when the constitution came into force.

In this report, Human Rights Watch uses the term “land confiscation” to describe instances in which the government, military, or private individuals claiming ownership appropriate via legal or extralegal means land that is already occupied or used by another. In most cases addressed in this report, the “legal” means by which government and businesses have acquired land fail to meet domestic procedural requirements and international legal standards, notably notice and compensation requirements.

Article 37 of Burma’s constitution establishes the state as the ultimate owner of all land in the country, while also recognizing the right to private property. Given this legal framework, Human Rights Watch uses the term “land use rights” to refer to the rights of farmers to work farmland. The term “claim to land” is used for individuals who may qualify for land use rights, particularly through inheritance or under a customary system, but have not yet registered land with the government. In Karen communities visited by Human Rights Watch, references to “ownership” were often made, as reflected in direct quotes of interviews.

I. Background

The population of Karen State has for decades suffered from armed conflict between the Burmese military and Karen armed groups, widespread human rights violations, and forced displacement and outflows of refugees. These have created a complex, competing, and overlapping governance system in the state that affects land ownership and use as well as access to justice.[3]

A nationwide census in Burma in 2014 recorded the population of Karen State as approximately 1,573,000. However, observers criticized the census for not including certain areas of Karen State, including conflict-affected areas covered by this report.[4] Most residents of Karen State are ethnic Karen, but there are also ethnic Mon, Shan, Pa-o, and Burman populations.[5] Most people earn their living in agriculture or animal husbandry.

Since Burma attained independence in 1948, ethnic armed groups, including those in Karen State, have operated in many areas along Burma's borders. After Karen nationalist hopes for independence at the end of British rule were left unrealized, the Karen National Union (KNU) and its armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), advanced the nationalist cause both politically and militarily.[6]

Successive Burmese civilian and military governments have sought to suppress the Karen nationalist movement. The Burmese military’s counterinsurgency strategy—known as the “Four Cuts” strategy aimed to cut insurgents off from food, supplies, intelligence, and recruits—resulted in widespread and systematic human rights violations and displacement. Several major waves of refugees fled over the border into Thailand to seek protection in the 1980s and 1990s. The military committed with impunity countless acts of extrajudicial killings, rape, torture, child soldier use, and abusive forced labor, as documented by Human Rights Watch and others.[7]

Internal divisions in Karen political and insurgent organizations have created difficulties in articulating or achieving a unified political position on behalf of the Karen. The KNU suffered a serious split in the mid-1990s, when the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army broke away in 1994.[8] Additional fractures occurred with the formation of the Karen Peace Force in 1997, and the KNU/KNLA Peace Council (KPC) in 2007. Various smaller “peace groups” run by retired military or non-state armed group officers also operate throughout Karen State.

In 2010, a large section of the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army broke away and renamed itself the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA), while other units transitioned to become various units of the Border Guard Force (BGF). BGFs are militia units that the government created after the adoption of the 2008 constitution to assimilate ethnic armed groups into the national army.

Conflict After the 2010 Elections

Karen State today remains a zone of intermittent armed conflict, though fighting has decreased dramatically since the signing of an initial peace agreement in 2012 and a nationwide ceasefire agreement in October 2015.[9]

In September 2014, fighting broke out between the Burmese army and the DKBA, causing thousands of villagers to flee their homes.[10] In early 2015, skirmishes continued between the DKBA and the army in Hpapun and Kawkareik.[11] Starting in July 2015, clashes occurred along the Asia Highway between Myawaddy and Kawkareik.[12] In February 2016, a BGF unit was attacked by remote-controlled landmines and gunfire along the same road.[13] Landmines generally remain a major problem, and reports indicate that fighters continue to plant new mines in the region.[14] In September 2016, clashes between DKBA units and BGF battalions #1011 and #1012 broke out in Hlaingbwe township, displacing nearly 4,000 civilians.[15]

In a July 2016 survey, The Border Consortium (TBC), an umbrella group of nongovernmental organizations, counted the number of refugees living in camps along the Thai-Burma border at 104,149, of whom about 79 percent are Karen.[16] A large number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) still living in Karen State face challenges in obtaining basic services including health care and education due a lack of humanitarian access. A 2014 TBC survey found there were approximately 400,000 IDPs in southeast Burma who are displaced due to armed conflict, generalized violence, large-scale development projects, or natural disasters.[17]

Many Karen have also migrated to Thailand for economic reasons. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), in 2015 the total number of Burmese migrants in Thailand was just under 2 million.[18] Human Rights Watch found that migrants face harsh and often abusive conditions upon reaching Thailand, including killings, torture, sexual violence, and extortion.[19]

Karen State Governance

Karen State governance is divided among government-controlled (as designated by the government) “white” areas, non-state armed group-controlled “black” areas, and mixed-controlled or contested “brown” areas.

The chief minister runs the state government, with various other state ministers covering portfolios such as transport, security and border affairs, forestry and mining, and social development, among others.

The KNU divides Kawthoolei (its name for the free state of Karen) into nominally civilian-administered districts that are each correlated with an armed group military brigade.[20] The KNU has its own governance systems delivering health care, education, and land and forestry regulation.[21] After the signing of an initial ceasefire agreement with the government in 2012, the KNU also opened offices to help liaise with the government.

Areas near Hpa-an, the state capital, are heavily government-controlled, while the KNU exercises greater control in border zones close to Thailand. In some areas, villagers continue to pay taxes to both the government and armed groups. Furthermore, in contested areas, business projects may require permission from both the government and the KNU, or from any combination of armed groups. Powerful business interests and companies, many of whom are former members of the military or ethnic armed groups, play a dominant role in local life.

Business Development Plans

Political reforms in Burma have promoted new laws and international agreements to enable investment, sparking plans for infrastructure development and special economic zones. Foreign investment in Burma reached US$8 billion in 2014-2015, double that of the previous year.[22]

At the national level, the government has accelerated plans to encourage foreign investment. In December 2015, parliament passed a new investment law, developed with the assistance of the International Finance Corporation (IFC).[23]

The new law consolidates the Foreign Investment Law of 2012 and the Myanmar Citizens Investment Law.[24] In addition to guarantees of regulatory stability for investors, it protects the government’s “right to regulate” in favor of human rights, including health and the environment.[25] In a reversal of prior drafts, the final version of the law removed a contentious investor-state dispute mechanism clause opposed by many civil society groups.[26]

Karen State is considered an attractive area for investment because of its abundant natural resources and strategic location on the Thai border. Construction of the Asia Highway, which the Asian Development Bank (ADB) asserts will “dramatically improve connectivity within Kayin [Karen] State, between the state and the economic hub of Yangon [Rangoon], and regionally between Myanmar and Thailand, and onwards across the GMS [Greater Mekong Sub-region],” is already underway.[27] A portion of the road, which links the border town of Myawaddy to Kawkareik, was financed by Thailand and is already complete. The second portion, financed by the ADB as part of its GMS East-West Economic Corridor project, will connect Kawkareik to Eindu, a small town close to Hpa-an.[28]

Hydropower is also being developed in the area, with seven dam sites planned along the Salween River, including the Hatgyi, Weigyi, and Dagwin dam sites in Hpapun district, Karen State, all backed by the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT).

In 2005, the Burmese government signed a Memorandum of Understanding to develop the Hatgyi dam site with EGAT, and pledged 60 percent of electricity flow to China, 30 percent to Thailand, and 10 percent to Burma.[29] The dam has been controversial, with protesters raising environmental, economic, and social concerns, and blaming the project for an increased Burmese military presence in the area.[30]

In 2011, the Karen State government opened the 1,000-acre Hpa-An Industrial Zone, where three factories were operating at time of writing.[31] Land around the industrial zone has reportedly tripled in value since its opening.[32]

Cement production is another source of investment, with a French-led factory near Hpa-an constructed in 1986, and two military-backed plants that caused relocation of at least five villages around 2000.[33] Four large-scale mining licenses for limestone extraction and at least 10 exploration permits have also been granted in Karen State.[34] In 2014, villagers in Mi Kayin village resisted development of a Chinese-led cement factory near the banks of the Salween River. At time of writing, the KNU’s refusal to grant permission has halted the project, though it still retains official government permission.[35]

Tourism has greatly increased in Burma since 2011, with the country on track to draw 7.5 million tourists in 2016.[36] Though most tourism to date is concentrated in Rangoon, Bagan, Inle, and Kyaiktiyo, the opening of four new crossings on the Thai border adds the potential for expansion of tourism in Karen State.[37]

Japan is a major supporter of investment in the area. The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is considering development in the Hpa-an to Myawaddy corridor, with plans for additional special economic zones that would utilize labor from displaced ethnic minority communities, including refugees living in camps across the border in Thailand.[38] In response, the Karen Peace Support Network, a network of Karen civil society organizations, has expressed concern over potential exploitation of low-wage workers and natural resources, and encouraged the Japanese government to consult with local communities on the planned projects and to protect vulnerable populations.[39]

II. Barriers to Realization of Land Rights

The following section presents a range of challenges faced by communities in Karen State, particularly farmers and other villagers in the Hpa-an area, as they try to maintain use of land they depend on for their livelihoods.

Intimidation by the Border Guard Force and Other Armed Groups

Human Rights Watch received several complaints of land confiscation that involved armed units operating in Karen State.[40] These cases ranged from alleged land grants by the government to more straightforward forced expropriations of land by Border Guard Force (BGF) commanders and various militias.

The BGFs often used intimidation to silence villagers’ objections—including firing assault rifles, bringing in armed soldiers to guard disputed land, and threatening villagers.[41]

Human Rights Watch witnessed firsthand BGF threats to detain villagers in relation to land confiscation in Hlaingbwe township. Villagers in Htantabin village in Hlaingbwe told Human Rights Watch of land appropriation by the BGF, which had built a compound near their farmland in 2012. U Be Be, who lives in the village, said when the BGF arrived in the area, they laid claim to the 20-acre plot used for sugarcane and vegetables that he said had been in his family for four generations, planning to divide the land into blocks and sell it for houses. BGF commanders resisted repeated requests by some villagers to show them their legal documents providing evidence of their right to the land, and insisted the land was in a military zone. U Be Be, like many of the villagers, said his family lacked documents for the land: “In 2013, we planted some rubber on that land. A year later, the BGF came to us and said that they would build a road on the land and they were going to divide the land into blocks 80 feet by 60 feet and sell it for houses.”[42]

In April 2015, a few weeks after villagers held a meeting about land confiscation in the area, a BGF commander arrived with two trucks filled with armed soldiers in an attempt to intimidate villagers from speaking out further. The dispute followed a series of efforts by a local family to get back land they claimed as their own from the BGF commander.

After a direct conversation with the BGF commander, who would not return the land to the family, the family matriarch sent a letter directly to the commander’s superior officer.[43]

While Human Rights Watch was visiting the village, the BGF commander arrived with armed troops and confronted the woman. “Why would you do this?” he shouted. “If you do this to me, I can arrest you.” The commander called to the soldiers outside, and six rushed into the house with ropes, threatening to tie up family members and take them to BGF headquarters. After protracted discussions, the BGF commander eventually withdrew with his troops from the village.

The villagers remained terrified of the BGF unit and told Human Rights Watch they felt it was hopeless to seek redress through direct contact with the BGF unit or higher levels within the BGF. They said that they were too fearful to initiate legal action against the BGF unit.[44]

In some reported cases, BGF units have acted on their threats to carry out arrests, including without apparent legal basis. In May 2015, in a different village in Hlaingbwe township, a BGF unit held a man, Yar Kut, in Mae Thein jail for four days regarding a land dispute in which the BGF claimed rights to land which the man’s family asserted they had been working for generations.[45] “They didn’t charge me, they didn’t tell me any number [of the penal code] that I broke in the law,” Yar Kut said. “They just said it’s because of the land.” He was he was held in jail for four days without charge, and only released from jail after his parents paid 50,000 kyat (US$41).

In some cases, armed groups stood guard over land for businesses seeking to develop the site.[46] In Mine Kan, villagers said BGF soldiers came to protect land claimed by the Kyaw Hlwan Moe Company for a 450-acre agricultural project on land claimed by villagers, who were actively protesting the project. According to villager Kaw Doe: “The company came to destroy the land [in early 2015] with big machines. Most of the land is destroyed now. They planted some teak and other trees just to show that they own the land.”[47]

Villagers said that armed soldiers from the BGF, led by Gen. Thein Zaw Min, had since come to guard the land. One local resident said: “The villagers don’t dare to go to that area anymore. The villagers are afraid because when the BGF came, they shot a lot, almost every day when they first came.”[48]

Daw Mu Pulu of Ateyebu village told Human Rights Watch that in 2006, Bo Sar Yay—who was in charge of a group of 10 DKBA fighters—seized the 20 acres of land she and her sister had inherited from her mother: “He started to plant teak and rubber on our land. He didn’t tell us anything. We wanted to complain but we were too afraid to say anything.”[49]

U Di Yay, a farmer in the village, said: “We are afraid of [the BGF]. They have guns. Even if we are angry we can’t argue very strongly because they have guns.”[50]

Smaller militias or “peace groups” have also been involved in land confiscation.[51] In February 2015, Human Rights Watch interviewed a group of villagers in San Klo, near Eindu.[52] The villagers complained that in 2013, Padoh Aung Sang, a member of the KNU who had left to form his own “peace group” in the late 1990s, had started to plant rubber on land owned and used by villagers for generations.

The villagers said they feared retaliation if they contested his seizure of their land. They stated that Padoh Aung San leads a local militia, the “Pyago Peace Group,” that consists of about 15 to 20 armed men living within 20 minutes of the village.[53] As Nu Yee explained:

Padoh Aung San and his armed group stay 10 minutes from here. When they came to plant the rubber, we didn't say anything to him because we were afraid of him. They have guns; they came with their guns when they checked the soil for planting.[54]

Even when less explicit threats are used, some villagers remain fearful because of the shadow of past abuses by BGFs and other armed groups in Karen State. The threat of violence by BGFs and other armed groups remains a reality in Karen State, which may explain why many farmers are reluctant to protest against the taking of their land when armed groups are involved.

In January 2015, Human Rights Watch interviewed seven villagers from Myaingyinu who were displaced due to fighting between the BGF and the DKBA in October 2014. One villager said: “The BGF shot at my house. I ran away to another village and stayed with my niece.… Sometimes I cannot sleep the whole night.… One of the BGF soldiers has beaten my son three times.”[55]

Villagers also said that BGFs continue to use forced labor:

The BGF told us we had to help them build a BGF camp. We worked for about a week, collecting bamboo. They didn’t pay us anything. The BGF soldiers speak rudely to the villagers, and threaten to kill them if they don’t do what they say.[56]

BGF leaders in one case refused to respect villagers’ requests that BGF personnel be stationed away from the children at the village school.[57]

Similar findings were reported by Karen Rivers Watch after interviewing displaced villagers.[58] Many BGF soldiers were also reportedly belligerent in areas they controlled. As one villager told Human Rights Watch, “When they are drunk, they shoot around and can hit the homes.”[59]

Forced Eviction and Destruction of Property

Villagers said police have destroyed houses and other property in response to protests or other efforts to prevent the seizure of land which villagers had long used.

New Ahtet Kawyin

In June 2015, police officers torched more than 100 houses in New Ahtet Kawyin village, west of Hpa-an, after evicting over 200 people. The eviction followed villagers’ attempts to reclaim land they said had long belonged to their village. Several elderly villagers told Human Rights Watch that local people had previously farmed the disputed area of land. One elder, Mu Htaw, said:

Before the government seized our land, we did taungya farming [shifting cultivation] in that area. We grew vegetables and collected bamboo shoots from the forest. We used leaves to shelter our houses from the rain.[60]

Villagers said that after they refused police demands in March 2015 to remove huts from the disputed land, they joined villagers from Kaw Sa Ka Lo village in a peaceful protest in Hpa-an on March 21, 2015, where police arrested 13 people under section 18 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law.

In June 2015, police began making arrests under the Forest Law. Twenty-seven men charged under articles 40 and 43 were later convicted, and served between two to six months in prison. Article 40 prohibits trespassing in a reserved forest, with a penalty of up to six months in prison and a fine of 5,000 kyat (US$4). Article 43 prohibits cutting teak trees in government forests, with a penalty of up to seven years in prison and a fine of 50,000 kyat (US$40). Villagers dispute that there were any teak trees on the land that they occupied.[61]

Villagers said that they had not seen any documents specifically naming individuals for arrest.[62] According to Daw Hla Nyut, 21, who was in the village: “The police came on June 2, 4, and 9, and they came to arrest people. If they saw any men [there], they would arrest them.”[63]

On June 15, Hpa-an police held a meeting in the village, informing villagers that they had one week to leave their homes. They also posted signs on fences notifying villagers that any houses not vacated by June 22 would be burned down. Most villagers decided to remain on the land. According to Daw Hla Nyut, “Many people had no place to go, and so they had to stay in the village.”[64] A week after the meeting, police officers came and destroyed the village. Tin Shwe, another villager, said:

On June 22, the police came. There were 20 cars and over 40 police and they hired some villagers from a different village to come with them. The police were wearing dark blue shirts. The police cut down all of the houses with chainsaws and they burned the bamboo houses.[65]

The house of 27-year-old Mu Kalote’s mother was among those destroyed, even though family members said they had no idea that the home was part of the disputed area and no signs had been posted indicating that they had to leave. According to Mu Kalote: “Two days after the police burned the village in New Ahtet Kawyin, they came to my mother’s house and destroyed it. We didn’t expect this. We had lived there for 16 years.”[66]

In February 2016, the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission concluded, in the event of an eviction of “squatters”:

Measures should be taken, based on humanitarian principles, such as, treating them humanely, giving educative talk prior to eviction, giving prior notices, making arrangements for transportation, providing assistance in health, education and social welfare needs and resettlement following the eviction.[67]

Obstacles in the Justice System

Several villagers said they faced arrest when peacefully attempting to defend their continued use of land they had been living on.

“In the past, even if you didn’t have documents for your land, nobody would arrest you,” one villager said.[68]

Human Rights Watch received several reports of charges against farmers whose land had been confiscated under section 447 of the penal code for “trespass” or “squatting.”[69] Charges were also brought for trespass under article 40 of the Forest Law against individuals foraging for food and materials in areas traditionally used by Karen as communal forests.[70] Since trespass is a criminal charge, those convicted face fines and prison.

Ka Sa Ka Lo

In Ka Sa Ka Lo village, police arrested a group of villagers who in March 2015 had built structures on land they said had been in their possession since their grandparents’ time, although they lacked documents to prove it. Six were charged with trespass under section 447 of the penal code. One of the villagers present said:

The [police] asked us questions about our land ownership. At the [police] station we were charged with [article] 447. Each person needed two guarantors to be released. It is 1 million kyat [US$800] guarantee.[71]

“This land is old land, owned by our grandparents,” Shue Kalay, a woman from the village, said.[72] A group of Kaw Sa Ka Lo villagers walked the land with Human Rights Watch, pointing out old trees planted by their grandparents and a stone post that marks the site of the village, and telling local folklore about a tiger living in the mountain at the base of the town. When Human Rights Watch visited the village again in August 2015, the farmers had managed to maintain their huts on the land.

Trespass cases often arise when villagers oppose claims by businessmen who receive government permission to take land. When farmers dispute such claims by attempting to return to the land as a form of protest, businesses file a complaint and police initiate trespassing charges against the farmers. “The businessman takes the land from the farmer,” said one lawyer. “But when the farmer protests, he becomes the criminal.”[73]

In these cases, farmers usually had little more than tax receipts from the government to argue for their claims to the land, which under Burmese law do not count as evidence of “ownership” against which a trespass charge may be defended.

Villagers often do not have the resources to defend themselves in court against criminal charges. As one villager whose land was confiscated for a hotel project said, “The hotel said, ‘If you don’t like it you can go to court against us.’ I want to go to court, [but] if you don’t hire a lawyer it doesn’t work. But I don’t have any money to pay a lawyer.”[74]

Farmers pointed out that the trials can become onerous, especially when government officials fail to appear, and complained that it is time consuming and expensive for them to travel to get to courtrooms—adding to the costs of defending themselves.[75]

Moung Pi, a villager from a town just outside of Hpa-an, was charged in 2013 with trespass after building a fence on land he claimed as his own. He said the cost of defending the suit was overwhelming: “I’ve nearly bankrupted myself trying to defend against the trespass suit. I had to sell another piece of land just to pay for the lawyer.”[76]

After being convicted of trespass, Moung Pi spent two months in prison with hard labor, working in an agriculture field: “I worked in the heat as a farmer. If you wanted a rest, you had to pay a 50,000 kyat [US$45] bribe.”[77]

Tokawklay

In Tokawklay village, land just outside the Hpa-an Special Industrial Zone is now the subject of a trespassing case instigated by U Khin Kyu, an influential local businessman who was an army general and government official in Karen State during the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) military government. Villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch indicated that they had claims to the land—showing tax receipts dating back to as early as 2004.[78] However, the value of the land near the zone has reportedly tripled since its opening.[79]

Villagers told Human Rights Watch they had put up a fence to demarcate the boundaries of their land in May 2014. Hpa-an police officers then came to the village and ordered the farmers to remove the fence. In July, after the farmers did not comply with the order, police filed trespass charges against seven villagers under section 447 of the Penal Code.

In June 2015, the Hpa-an court convicted six of the villagers—U Ne Win, U Myint I, Maung Kyaw Klone, U Ti Lone, U Tin Win, and U Shwe La Nge—and ordered them to each pay a 500 kyat (US$0.40) fine. While the final fine was nominal, the villagers said that at many of the 21 court hearings they were compelled to attend, government officials failed to turn up, delaying the trial and adding to the cost of defending the suit. Villagers added that it was difficult to travel to court, and each time their effort to go to court prevented them from working the entire day. The six convicted farmers estimated that they each spent 440,000 kyat (US$360) defending themselves against the charges.[80]

Farmers find it difficult to obtain lawyers who will represent them against powerful figures in the community. Lawyers in Hpa-an and Rangoon said that few lawyers in Hpa-an were willing to take on land cases.[81] To defend high-profile cases in Karen State involving political activists, legal aid lawyers had to be brought in from other parts of the country.

At time of writing, there is no institutionalized legal aid infrastructure to assist farmers with their land issues.[82] While nongovernmental legal aid services have cropped up throughout the country, few such activities are currently being undertaken by civil society groups in Karen State.[83]

Lack of Free Expression and Assembly

Many farmers said that positive initiatives by the newly elected government meant that, unlike in the past, they could now raise their voices against governmental abuses.[84]

However, as farmers gain confidence to speak out in public spheres, charges related to protests are becoming increasingly common. The authorities and local police frequently deny applications for demonstrations; those who protest without permission face arrest and charges under section 18 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law.[85]

According to one activist, some 40 to 50 people are currently detained in Hpa-an prison in relation to land issues.[86]

Nongovernmental organizations in Hpa-an repeatedly expressed frustration over the restrictive environment imposed by the local government. In October 2015, the Hpa-an township General Administration Department (GAD) issued an order prohibiting domestic and international nongovernmental organizations from holding meetings in hotels without first obtaining official permission from the township.[87] The letter stated no apparent rationale for the decision.

Since 2014, protesters said authorities were unresponsive to requests to hold demonstrations against land confiscation, and that several of those who decided to protest without official permission were arrested. For example, Saw Maung Gyi, leader of the 88 Karen Student Generation Organization, which was prominently involved in organizing protests in Karen State, reported that on August 16 and 18, 2014, organizers sought police permission to protest, but were ignored:

We officially requested permission to protest peacefully but [the police] didn't reply to us until the night before the protest would take place. If we have to do things according to the law, they are responsible to get back to us in 48 hours prior to a demonstration but police officer [name withheld] said that he failed to reply to us just because he was so busy that night. So we prepared everything necessary and went to protest anyway.[88]

Although they say the protest was peaceful, local police arrested 10 people—six farmers and four activists. The Hpa-an court sentenced four activists to four months in Hpa-an’s Taungalay prison. Farmers had to pay a fine but avoided any prison time. The activists allege they were kept in solitary confinement for 10 days in prison before they were allowed to interact with others.[89]

Similarly, in March 2015, a group of nearly 300 people organized by the 88 Karen Student Generation Organization to protest their problems securing land in Karen State decided to go ahead with their demonstration, despite lack of official permission. Although the protest was peaceful, police called a number of participants to the Hpa-an police station the next day for questioning and charged 13 people under section 18 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law.[90] The protesters secured bail after guarantors provided a financial guarantee of 2 million kyat (US$1,600) per person.[91]

The activists also faced intimidation and threats of closer police surveillance. Saw Maung Gyi was charged on August 17, 2015, on trumped-up charges under section 17(1) of the Unlawful Associations Act and sentenced in November 2015 to two years’ imprisonment. He ended up spending four months in solitary confinement until he was released on parole through a pardon from then-President U Thein Sein on January 22, 2016.

After assuming office in April 2016, the NLD-led government of President U Htin Kyaw released scores of political prisoners, including prominent land rights activists and community leaders imprisoned for their activities connected to defending land and natural resources.

In May 2016, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) estimated that 86 people were in prison for politically related offenses and exercising their civil and political rights.[92] Observers noted that a significant number of these political prisoners were imprisoned for their work related to land issues.[93]

Lack of Notice, Consultation

Human Rights Watch found that in general the state and local governments, or companies involved, did not provide villagers with notice that would allow them to contest a proposed sale or confiscation, or even plan ahead for relocation.

Tin Shwe from New Ahtet Kawyin village, where police torched more than 100 houses in June 2015 after evicting 200 people, told Human Rights Watch: “We never had a chance to explain. The government just sent a letter to the village chief and then he had to stick it up on the fence.”[94]

The provisions of the Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Act (“Lands Management Act”) and the Farmland Law provide farmers the opportunity to contest land sales that affect their historical land use. The Farmland Law requires that a notice for objection be posted at the township department office as well as ward/village tract administration office pertaining to the land in question. The objection should be filed within 30 days after the notice was issued.[95]

Similarly, the Lands Management Act requires the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (“Agriculture Ministry”) to notify the public by posting an objection form on the notice board of the “Naypyidaw Department Office or Regional or State Department Office, the District Department Office, the Township Department Office, and the Administrator’s Office of the ward or village tract where the vacant, fallow and virgin lands are located.” Individuals have 30 days from notification to object to the proposal.[96] During this period, the Agriculture Ministry must inquire into whether the allegedly vacant lands are truly vacant, and “whether there is a holder currently utilizing the land,” among other things.[97]

In practice, villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch did not receive these notifications nor were such measures apparently applied. Consequently, many were not aware of impending projects until it was too late to formally object under the regulations.

Agriculture Ministry officials told Human Rights Watch that most land problems occur between investors and villagers or government and villagers. They conceded that notice was a fundamental issue with the land system, and while farmers have the right to object to land sales, most often they do not.[98]

In some instances we documented, villagers received no advance notification at all about a governmental project, only finding out about the project when their paddy fields were flooded or construction on a new project began.[99]

In Naw Kyaw Myine village, more than 3,000 acres of land were flooded by the Ye Bo irrigation dam project initiated by the Agriculture Ministry in 2009. Despite villagers’ claims to the land, when the dam project planning started in 2006, the government did not inform most villagers of their impending land loss. Aung Thay, a local man who organized and collected documentation to oppose the dam, said:

The government called the district and village tract administrator and made a decision. There was no consultation with the villagers. The village administrator did not share information about the project. He only invited leaders from only three of the four affected villages to a meeting about the dam.

He added that villagers were dismayed over the loss of their ancestral lands: “It feels like we lost our parents.”[100]

In late 2014, the Agriculture Ministry built a new channel for the dam, affecting another 10 acres and displacing two more families. Again, families reported that they received no notice of the impending flood or compensation.

In addition, most farmers received no advance notice when the land they were using was sold to private parties, in many cases only learning of the sale after its execution. Mit Tarlar, a villager from a town outside of Hpa-an, told Human Rights Watch that the government developed the land without consultation with local people, who were not given a chance to raise their objections.[101]

Another villager, Hla Khin, said he was not even notified of the government meeting with the affected community: “They didn’t invite us to the meeting because we do not own large parcels of land. They only invited landowners with over five acres of land.”[102] Hla Khin owned less than one acre of land. He said that he had had plans to use the land to build a house for himself and his wife.

In a few cases, government officials visited the village or issued a written notice that farmland would be repurposed but then failed to provide information about the scope of the project, or its impact on farmland. One villager said of the Hpa-an Special Industrial Zone: “The big problem is that we do not know the size of the industrial zone. We do not know whether it will reach our land or not, and we don’t know whether we can register land that is not yet registered.”[103]

In other cases, consultation was offered but did not provide villagers with a meaningful opportunity to give views and inputs into plans for the zone.

With respect to the Hpa-an Special Industrial Zone, of which foundations were laid in December 2011, the government’s consultations about land with villagers were cursory and incomprehensible to many attendees. According to farmer U Ne Win, in May 2014, Special Industrial Zone authorities invited villagers from affected communities to a meeting regarding the industrial zone; however, it was conducted in Burmese, which most Karen villagers do not understand.[104]

This lack of adequate notice by government officials puts people who would contest a sale or development of land at a severe disadvantage. Discussions with local lawyers in Hpa-an indicated that any legal appeal of a land transfer will likely be rejected if the buyer already has received the proper forms from the government.[105]

Further, as described below, the grievance mechanisms put in place by the Farmland Law fail to provide an adequate substitute for a court of law in deciding such issues. As a result, failure to properly notify individuals of proposed land projects often results in a nearly uncontestable legal transfer of land without input from those utilizing the land.

Difficulties Demonstrating Land Claims

Prior to the 2012 land reforms, tax receipts were the only form of documentation available to farmers. Among farmers who spoke to Human Rights Watch, they were the form of documentation most commonly held.

However, while tax receipts document land use they are not a legal document that can be used to certify land ownership. As such, they do not protect against government confiscation and government officials have been unwilling to consider these when making land grants.

Human Rights Watch found numerous cases of farmers who had worked land for years and had recorded their land and paid tax to the government, but then lost the land to the government, or businessmen or non-state armed groups who had obtained more recent government certification of ownership of the land.[106]

For example, U Muu Tay from Ta Nyin Kone village said local residents had been working the land since 1985 and had registered the land with the government in 1999. From 2000 to 2006, the villagers regularly paid tax on the land, and received receipts for those payments.[107] In 2006, he said, the DKBA came:

When they first arrived, they told us that we owned the land. But later they took 500 acres [of the land tax had been paid on] for their own plantation. They never offered us any money for the land. Since the DKBA took the land, we haven’t received any tax payment requests [for that land] from the government.[108]

Despite recent legal reforms related to land rights, there has not been significantly improved land tenure for farmers whose claims were not already registered at government offices. Only since 2012 have farmers been able to access Land Use Certificates (LUCs), which contain the right to sell, exchange, and lease land in a manner comparable to a system of private property rights.

Most of the villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch had not received LUCs for their land, which are supposed to be given to all individuals with farmland currently on record with the Agriculture Ministry.[109] Those interviewed said that apparently as a result of the poor registration and documentation system, there were frequent mismatches between the land use maps in possession of the land office and actual land use in communities.[110]

For example, some farmers affected by the newly opened Hpa-an Special Industrial Zone showed Human Rights Watch tax bills paid to the government for use of their land and maps from local government land administration offices marking use rights to the land that they allege the government has now taken for the zone.[111] The dates of the documents varied, with some having been issued as far back as 2004.

Villagers stated that the government had not recognized their claims to the land nor given them any compensation. One aggrieved villager said, “They [government officials] look at the maps in the land office but they don’t compare them to the real use [of the land],” pointing out that the current land office maps do not reflect the community’s historical use of the land.[112]

Even where farmers possessed some form of documentation for their land, Human Rights Watch found that it often provided little protection against confiscation.[113]

U Lwan Kyaw, 72, one of several villagers who said their land was taken for the construction of the Zwebakin Hotel on the outskirts of Hpa-an, said that efforts to prove his ownership with records were dismissed: “We sent a letter to Shwe Mann [then speaker of the national parliament] but didn’t get any response. Before the hotel came, the land office said, ‘The government has taken the land, you cannot have it.’”[114]

Villagers presented Human Rights Watch with documents that showed they had paid taxes for the right to use the land, as well as maps provided by the local land office indicating that their names were on record at the local government offices as the farmers utilizing the land.[115] U Lwan Kyaw said that in 2013, he and his wife approached the local land administration office for assistance, but officers there told them they could do nothing to help. Later, the General Administration Department under the Ministry of Home Affairs told villagers they should go to court if they were unhappy with the decision.

Burma’s land registration system primarily focuses on farmland that has already been recorded.[116] As a result, LUCs have been issued only to those whose rights to land are already on record. Farmers that are actively using land but whose rights have never been recorded have still not benefited from the new registration systems. The registration maps on record are notoriously outdated, in some cases with maps dating back to the early 1960s.[117]

Further, the government’s land registration system appears ill-equipped to address the problems faced by people living in rural, ethnic, or conflict-affected areas, where farmers find it difficult to access government services and thus obtain registration.[118]

Registration in conflict-affected areas is particularly low. According to one study, fewer than a quarter of farmers in these areas have land documentation.[119] Humanitarian access is coordinated through the state chief minister’s office but is not comprehensive, leaving many internally displaced persons without access to personal identification documents, which are necessary to show to government officials when seeking land registration.[120]

Many of these farmers in conflict-affected areas possessed no government-registered land documents whatsoever; neither tax documents nor LUCs.[121] In these communities that Human Rights Watch visited, land ownership was recognized through community practices based on physical boundaries and historical land use, resulting in arrangements in which all the villagers knew who possessed which piece of land.[122] During times of conflict, when villagers either abandoned land or were prevented from accessing government services to pay land use taxes, the community land practices were simply not recorded or maintained.

In addition, LUCs cover only farmland, whereas many earn livelihoods in Karen State from land other than farmland.[123] One common example is land used in a shifting cultivation system. In some cases, land that is classified as vacant, fallow, and virgin by the government may actually be land that is part of the local community’s taungya (shifting cultivation) practice in which crops are rotated and sections of land are left vacant for periods for the soil to recover.[124]

There is currently no form of land title available to protect this type of use, meaning that farmers must attempt to request that the government transfer classification of such land to farmland before the use rights can be documented.[125] In the meantime, the government may determine that land is vacant, fallow, or virgin, and grant land use rights to others without protecting the rights of villagers who have traditionally used the land. As noted above, while individuals under the law have the right to contest such grants, they are rarely informed in a timely manner so as to do so.

Human Rights Watch also encountered some villagers with land registration documents issued by the insurgent Karen National Union. At times, land recognition by the government and the KNU came into conflict.[126] In some conflict-affected areas, villagers perceived the possession of KNU land registration documents as putting them at grave risk. One villager from Hlaingbwe township, an area now controlled by the Border Guard Force, explained that she had at one point received registration documents from the KNU, which evidenced her family’s ancestral possession of the land: “In the past, we had documents from the KNU. But if the military sees KNU documents they will kill you, so we threw them away.”[127]

Problems with Local Land Administration Offices

Farmers reported problems dealing with government offices in charge of administrating the land system, particularly when they were seeking to register land.

Academic research has found that Settlement and Land Records Department (SLRD) offices are severely understaffed and do not have adequate capacity to perform their legal and regulatory functions.[128] Interviewees also indicated that offices made little effort to respond or fulfill requests put forth by farmers, and many villagers told Human Rights Watch that they perceived the offices as focused solely on furthering the interests of businesses or wealthy individuals.

In Karen State, several factors make it difficult for farmers to access the SLRD. Many farmers do not speak Burmese and are illiterate; the government has not undertaken serious efforts to ensure that its land offices in Karen State have officers who can speak Karen.[129]

Illiteracy and an inability to speak Burmese means that language is a major barrier for villagers seeking to access government services. “It is not easy for me to communicate with government officials,” said one villager. “I don’t speak Burmese and they do not speak Karen.”[130] This language barrier has led farmers to sign documents that they did not fully understand.[131]

Farmers stated other practical factors, such as poor road conditions and lack of public transport, that made it difficult, time consuming, and expensive for them to travel from remote rural areas to the records departments, which are based in cities.[132]

Villagers also alleged that in many cases, SLRD officers failed to perform their duties or demanded bribes to do so. Several villagers stated that the SLRD did not respond to their inquiries, claiming that officials were out to lunch, that the weather was “too hot” to travel to their village to measure the land, or other apparent excuses.[133] In one village, farmers reported having to bribe officials with 400,000 kyat (US$325) simply to get them to visit their land.

In some instances where village leader permission was sought, farmers complained that they were unresponsive, refused to perform their duties, or were corrupt.[134] In one village, the local village leader is said to have told villagers that he expected to receive new motorbikes in exchange for his acquiescence.[135] Other farmers also stated they believed village leaders took pay-offs from people and groups trying to get ownership of land.[136]

|

San Klo Villagers from San Klo,[137] near Eindu, said the local land administration office provided little support in their attempt to fight a land grant given to a former Karen armed group commander—Padoh Aung Sang, a KNU member who had left to form his own “peace group” in the late 1990s—without adequate consultation with local communities who had historical ties to the land. Although the villagers’ use of the land had been recognized by the government through the granting of usage rights, such documents offered no protection when they sought help at the land administration office against Padoh Aung Sang’s appropriation in 2013 of more than 100 acres on which he planted rubber trees. Nu Yee, one of several farmers who met with Padoh Aung San’s family at the local land administration office, said: We went to the land office in September 2014 and we showed them our [tax] documents. They asked us questions about how long we have lived on this land. Padoh Aung San’s family was summoned as well. After that we went back to the land office four or five times to discuss who owns the land. They said there is nothing we can do for you. There was no explanation.[138] Villagers added that they had asked the local land administration office to do a site visit, but the office had yet to do so. Nu Yee said: “The land office said, ‘It is too hot to measure your land,’ and it never came back to measure. We tried to phone them but there was no answer.”[139] Villagers said they had received no compensation from Padoh Aung San for their land and could only support themselves with help from relatives abroad. Nu Yee added: “We have given up. We have no job or source of income anymore.”[140] |

Nonexistent or Inadequate Compensation

In most of the cases that Human Rights Watch documented, people who had had their land seized received no compensation. This was true even where villagers could produce some form of documentation providing evidence of government-recognized land use rights.

Aung Thay from Naw Kyaw Myine village said the government provided no compensation and that most farmers in his area, including almost “80 percent of the village youth,” had to go to Thailand when it flooded their land for a dam project.

“Now I’m just planting rubber and other small plants,” another farmer from the village said. “I have six kids. Two are in Thailand and one is in Malaysia.”[141]

Villagers in Htantabin village, Hlaingbwe township, said they had tried speak to the Border Guard Force commander of the area, requesting compensation for their destroyed rubber trees: “We told him we wanted some compensation for the rubber [trees] that we had planted. He said to us, ‘Who told you to plant rubber on that land?’ He wouldn’t give us any money.”[142]

Failure to compensate occurred even in a number of cases involving official taking of land by the government for a public purpose under the 1894 Land Acquisition Act, which requires the government to provide compensation.[143]

In cases where villagers were compensated, many said it fell far short of what they were owed or what allowed them to earn a sustainable living or even survive.

In June 2015, the BGF commander offered to give the villagers five blocks of the developed land, significantly less than the 20 acres they claimed. According to villager U Be Be:

Now the commander has offered to give us five blocks of the land, but it is not the same.… My grandmother on my father’s side is already old, she cannot work. If I can work that land I can give some money to my grandmother. If we lose that land, I will be very upset.[144]

Villagers from New Ahtet Kawyin also said that the land which the Karen State government offered before they were evicted in 2015 was not sufficient for all of the families to move to. The government told villagers they would determine who could receive land plots through a so-called lucky draw.[145] One of the villagers explained that the plots on offer were too small to earn a sufficient livelihood:

The plot [offered by the government] is 40 by 90 feet. On land that size we can only build a home, we cannot make anything or do farming. We cannot even build an outhouse. Also, there are some farmers who have small plantations already on that land. How can we know that we are not taking their land?[146]

Moung Pi, from a village just outside of Hpa-an, said that despite possessing an executed land sale contract and land tax receipts, the government confiscated his land without compensation. He noted: “It is good land. You could not work in Thailand for 10 years and make enough money for this kind of land.”[147]

Mit Tarlar from Ta May[148] said that the two parcels of land sized 60 by 160 feet that the government offered to compensate him for his 5-acre plot was woefully inadequate:

We cannot do farming on the land [given for compensation] because it is so small. You can only build a small house.… The economic situation is worse here since we lost the land. There aren’t a lot of jobs here. All of our sons and relatives had to go to work in Thailand.… I only have the house I am living in now because I went to Thailand to work.[149]

In the case of the newly opened Hpa-an Special Industrial Zone, villagers told Human Rights Watch that they were not offered any compensation for the land, though they reported that other people dispossessed of land within the zone did receive other land.[150] U Ne Win, whose eight acres was flooded by a dam built within the zone, told Human Rights Watch that he was still waiting for the government to fulfill its promise to give him land. In the meantime, his sons and daughters had moved to Thailand to find work to support the family.[151]

Government officials did not appear to apply consistent criteria for determining the amount of compensation. When determining compensation, officials did not take into account the livelihood impact of the land confiscations.

In Kaw Klone village, then-chief minister U Zaw Min promised the return of land confiscated for rubber plantations.[152] However, when Human Rights Watch visited the village in March 2015, villagers indicated that only 186 acres out of a total of 700 acres had been returned.[153] In another case, villagers were told that they would receive new land, only to discover that the new land in question was already claimed by other people.[154] As one farmer said, “The government offered us new land, but we cannot move there because our neighbors already own that land.”[155]

Others have yet to receive the land promised, and have no information as to when or whether it may come. One villager dispossessed by the Hpa-an Special Industrial Zone said: “Two years ago the government built a small dam and it flooded our land.… The SLRD [Settlement and Land Records Department] has promised new land but we still haven’t received anything.”[156]

In a few cases, businesses involved in land seizures offered token payments aimed at placating those whose land was confiscated. Villagers told Human Rights Watch that they refused to accept such payments, which they did not consider to be fair compensation for their land. In the case of the Zwekabin Hotel described above, villagers are still seeking compensation from the company. They said that they have received a 1 million kyat (US$800) “donation,” but not actual compensation for the land.[157]

The instances in which villagers were successful in obtaining compensation often came through political, rather than legal, means.[158] For example, in some cases villages banded together with the assistance of an influential Buddhist monk, the help of a local nongovernmental organization, or through a well-educated individual within the village, such as a school teacher or headmaster. The most successful strategies for obtaining compensation or the return of land appeared to be appealing directly in writing to the Karen State chief minister at the time, U Zaw Min, or then-President Thein Sein. In other cases, villagers sought assistance of non-state armed groups with political clout in the area to help negotiate an acceptable outcome.

In the rare instances when the government has admitted an error in seizing land, redress has been limited. Villagers in Kaw Klone said that the Karen State government had eventually acknowledged in a letter to the villagers that their land was improperly confiscated in 2008 by a wealthy businessman, Myit U, who had forced them to pay to keep the land and threatened violence against those who could not or would not pay. Despite this admission, they said, more than 1,000 acres of their land have yet to be returned, and some of the returned land is now in the hands of non-villagers. A Kuklo visitor said:

Chief Minister U Zaw Min now said that he has given back 700 acres of land, but in reality, they’ve given it to businessmen, cronies. We received a document that lists land return for 58 individuals. But some of the people on the list are not from this village. About 30 [people] from the village are missing from the list. Villagers from here got back only 186.31 acres.[159]

Recognizing land to be one of the most pressing issues facing the country, the government in 2012 established a Land Acquisition Investigative Commission to deal with complaints of improper land confiscation, though the commission has no authority to actually resolve cases. In its first report issued in 2013, the commission concluded that most land acquisitions broke existing land laws.[160]

The commission noted that more than 117,000 acres were acquired for industrial zones, agriculture projects, or urban growth.[161] It found a lack of transparency between government, businesses, and individuals. It further found that, though required by law, most projects which were incomplete had not reverted back to the original landowners.[162]

If compensation was paid, it was most often well below market level.[163]

In April 2016, Burma’s parliament announced it would investigate 6,000 out of some 18,000 complaints in its next term.[164]

Loss of Livelihood, Migration to Thailand

Like much of Burma, Karen State remains a primarily agrarian society where individuals rely heavily on rice production for incomes.[165] Access to land is central to livelihoods, as there are few other methods to earn income. One farmer, who lost her land and did not know what other job she could do, said, “I know everything about rice farming, but I have no other education. I did not go to school.”[166]

A family’s loss of land typically results in significant loss of earnings, and the resulting harm to livelihoods and food security can place immense burdens on those for whom there is little or no economic cushion. Government policies that facilitate unlawful or uncompensated land seizures reflect a failure to take adequate steps to ensure everyone’s rights to an adequate standard of living, including food and shelter.[167]

Htee Htar from Ta Nyin Kone described the impact the loss of land has had on his village: “With no land, we cannot do farming and we cannot make a business. Since 2006 we have been working as day laborers in other fields.”[168]

Daw Mu Pulu from Ateyebu said that after DKBA soldiers seized her 20 acres of land in 2006, she became a day laborer and others in her family were compelled to become migrant workers in Thailand. While they occasionally sent her money, the situation had deteriorated since they farmed their own land. She said: “Now we only make 3,000 kyat (US$2.40) per day and we have to buy rice. If we had our own paddy, we could grow our own rice.”[169]

Despite the recent establishment of factories and agricultural plantations around Hpa-an, villagers claim that the factories and plantations have created few jobs for local people. They say that instead, the businesses are employing laborers from other parts of the country who may be in debt and thus accept very low wages.[170] The vice chair of the Hpa-an Special Industrial Zone told Human Rights Watch that he estimated that only 30 percent of workers employed at the Hpa-an Special Industrial Zone are from Karen State.[171]

Families have also been fractured by land confiscations. Human Rights Watch found in the cases examined that land confiscation in Karen State almost always prompted migration for work to Thailand by at least one member of an affected family.[172]

Kaw Sa Ka Lo villagers said that after their land was seized, “most of the young people went to Thailand.”[173] One villager, whose brother is now in Thailand, told Human Rights Watch: “We just want our land back. We have large families but no land for our children. Our brothers and sisters are in Thailand now. They want to come back but there is no land to support them.”[174]

An elderly woman said, “Now that I have no farm … my family in Bangkok sends me money to support me.”

Many individuals said that they would have preferred to keep their families intact and would not have migrated were it not for the confiscation: “After our land was ruined, about half of the young people left for Bangkok. Before the factory came, we were happy farming; we could create jobs for the youth.”[175]

Those who lost land and wished to stay were sometimes able to rent farmland from neighbors, borrowing money from relatives living abroad.[176] Other landless farmers who were determined to remain in their area turned to day labor if it was available: “We have nothing to do now. We are just looking for new land, and some of us do day labor. With day labor we earn 3,000 or 4,000 kyat (US$3-4) per day.”[177]

Land confiscation has led to cross-border migration for some, but many have migrated to Thailand for economic reasons apart from land confiscation. Overall, migrants to Thailand often face poor working conditions and exploitation. “Our relatives want to come back,” said one villager. “The working conditions [in Thailand] are poor and the salary is low.”[178]

Lack of Redress

Villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch repeatedly cited the lack of compensation or other forms of redress when their land had been seized. “It’s like hitting a cement wall,” one community leader said.[179]

When a land dispute arises, the first avenue of recourse for villagers is with the Ward or Village Tract Farmland Administration Body. The committee consists of a chairperson from the General Administration Department, a secretary from the Settlement Land Records Department, and two farmer representatives. It is unclear what processes or criteria are used to select farmer representatives.

From this first level committee, contested decisions can be appealed to the township, district, and ultimately region/state level Farmland Management Bodies. Redress becomes more difficult when land disputes cannot be resolved at the ward or village tract level.

Farmers typically said their ward or village tract representative had been their initial point of contact in expressing a complaint over a land problem.

Local representatives frequently were unable to resolve the disputes. National-level Agriculture Ministry officials conceded that farmer representation at the district and region/state level was weak, and said this was because the farmer organizations were weak.[180] This suggests that farmers’ interests are likely to be less well-represented the higher their appeal goes.

While the land administration system allows for review of local level decisions, there is no mechanism to challenge or review decisions by an independent administrative or judicial body.[181] Under the 2012 Farmland Law, decisions made by the Farmland Management Body regarding land classification and land ownership may not be appealed in a court of law.[182]

The Ta Nyin Kone case highlights the difficulties faced by villagers seeking redress for land confiscation.

Ta Nyin Kone

In the village of Ta Nyin Kone, locals started experiencing land problems after a DKBA unit arrived in their village in 2006. U Muu Tay, a local villager, said the villagers had been working the land since 1985 and had registered it with the government in 1999. From 2000 to 2006, the villagers regularly paid tax on the land, and received receipts for those tax payments.[183] But in 2006:

The DKBA came. When they first arrived, they told us that we owned the land. But later, they took 500 acres [of the land we had been paying tax on] for their own plantation. They never offered us any money for the land. Since the DKBA took the land, we haven’t received any tax payment requests [for that land] from the government.[184]