Summary

State security forces in Ethiopia have used excessive and lethal force against largely peaceful protests that have swept through Oromia, the country’s largest region, since November 2015. Over 400 people are estimated to have been killed, thousands injured, tens of thousands arrested, and hundreds, likely more, have been victims of enforced disappearances.

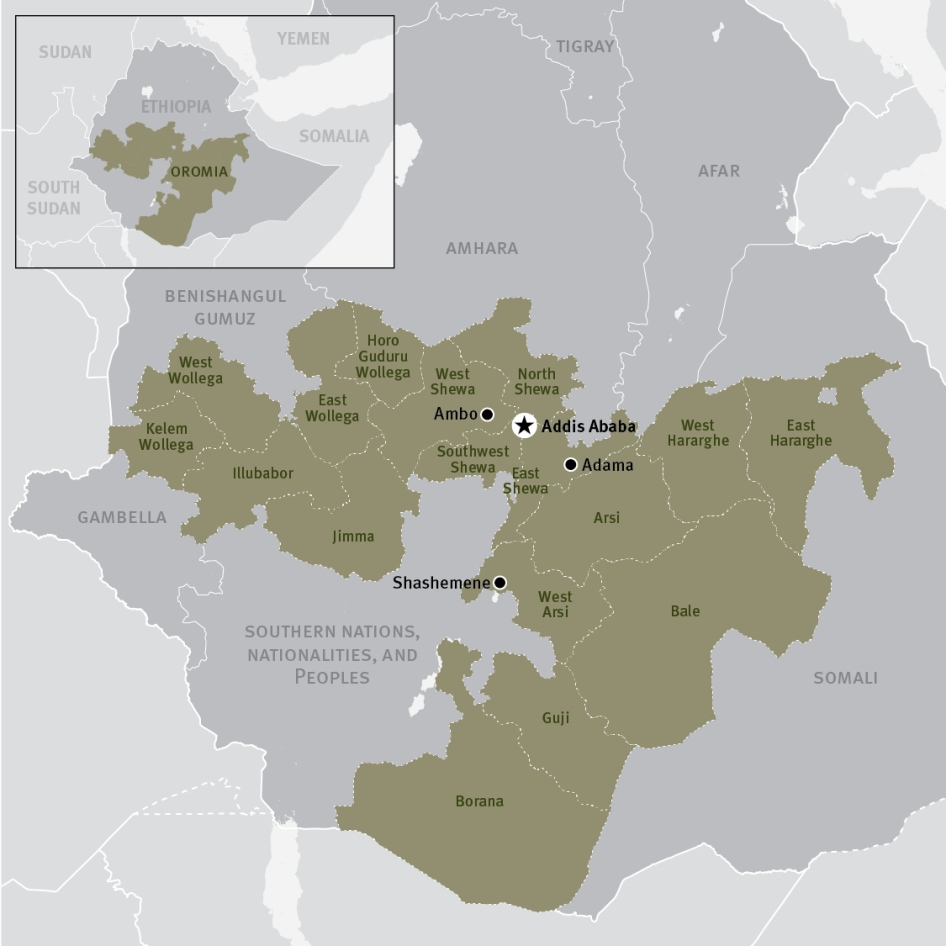

The protests began on November 12, 2015, in Ginchi, a small town 80 kilometers southwest of Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, which is surrounded by Oromia region and home to most of Ethiopia’s estimated 35 million Oromo, the country’s largest ethnic group. The decision of authorities in Ginchi to clear a forest and football field for an investment project triggered protests in at least 400 different locations across all the 17 zones in Oromia.

Security forces, according to witnesses, shot into crowds, summarily killing people during mass roundups, and torturing detained protesters. Because primary and secondary school students in Oromia were among the early protesters, many of those arrested or killed were children under the age of 18. Security forces, including members of the federal police and the military, have arbitrarily arrested students, teachers, musicians, opposition politicians, health workers, and people who provided assistance or shelter to fleeing students. Although many have been released, an unknown number of those arrested remain in detention without charge, and without access to legal counsel or family members.

This report is based on more than 125 interviews with witnesses, victims, and government officials. It documents the most significant patterns of human rights violations during the Oromo protests from late 2015 until May 2016.

In November 2015 when the protests started, protesters initially focused their concerns on the federal government’s approach to development, particularly the proposed expansion of the capital’s municipal boundary through the Addis Ababa Integrated Development Master Plan (“the Master Plan”). Protesters feared that the Master Plan would further displace Oromo farmers, many of whom have been displaced for development projects over the past decade. Such developments have benefitted a small elite while having a negative impact on local farmers and communities.

Human Rights Watch’s research indicates that security forces repeatedly used lethal force, including live ammunition, to break up many of the 500 reported protests that have occurred since November 2015. The vast majority of protesters interviewed described police and soldiers firing indiscriminately into crowds with little or no warning or use of non-lethal crowd-control measures, including water and rubber bullets.

Security forces regularly arrested dozens of people at each protest, and in many locations security forces went door-to door-at night arresting students and those accommodating students in their homes. Security forces also specifically targeted for arrest those perceived to be influential members of the Oromo community, such as musicians, teachers, opposition members and others thought to have the ability to mobilize the community for further protests. Many of those arrested and detained by the security forces have been children under age 18. Security forces have tortured and otherwise ill-treated detainees, and several female detainees described being raped by security force personnel. Very few detainees have had access to legal counsel, adequate food, or to their family members.

Many of those interviewed for this report described the scale of the crackdown as unprecedented in their communities. As 52-year-old Yoseph from West Wollega zone put it, “I’ve lived here for my whole life, and I’ve never seen such a brutal crackdown. There are regular arrests and killings of our people, but every family here has had at least one child arrested… All the young people are arrested and our farmers are being harassed or arrested.”

The Ethiopian government has claimed that protesters are connected to banned opposition groups, a common government tactic to discredit popular dissent, and has charged numerous opposition members under the country’s repressive counterterrorism law. Respected opposition leader Bekele Gerba is one of 23 senior members of the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), a legally registered political party, who have been charged under the counterterrorism law after spending four months in detention. Bekele has been a staunch advocate for non-violence and for the OFC’s continued participation in Ethiopia’s flawed electoral processes. Students peacefully protesting in front of the United States embassy in Addis Ababa have also been charged under the criminal code.

Students’ access to education, from primary schools to universities, has also been disrupted in many locations because of the presence of security forces in and around schools, because teachers or students have been arrested, or because students are afraid to come to class. Schools were temporarily closed by government officials for weeks in some locations to dissuade protests.

The brutal response of the security forces is the latest in a series of abuses against those who express real or perceived dissent in Oromia. Between April and June 2014, security forces killed dozens of people when they used excessive force against demonstrators in western Oromia who raised concerns about the Master Plan. To date the government has failed to conduct or support an independent investigation into the killings and arbitrary arrests in 2014.

The Ethiopian government has also increased its efforts to restrict media freedom – already dire in Ethiopia – and block access to information in Oromia. In March, the government began restricting access to social media sites in the region, apparently because Facebook and other social media platforms have been key avenues for the dissemination of information. The government has also jammed diaspora-run television stations, such as the US-based Oromia Media Network (OMN), and destroyed private satellite dishes at homes and businesses.

The Ethiopian government should drop charges and release all those who have been arbitrarily detained and should support a credible, independent and transparent investigation into the use of excessive force by its security forces. It should discipline or prosecute as appropriate those responsible and provide victims of abuses with adequate compensation. These steps are essential to rebuild much-needed confidence between the Oromo community and the Ethiopian government.

Ethiopia’s brutal crackdown also warrants a much stronger, united response from the international community. While the European Parliament has passed a strong resolution condemning the crackdown and another resolution has been introduced in the United States Senate, these are exceptions in an otherwise severely muted international response to the crackdown in Oromia. Ethiopian repression poses a serious threat to the country’s long-term stability and economic ambitions. Concerted international pressure on the Ethiopian government to support a credible and independent investigation is essential. Given that a national process is unlikely to be viewed as sufficiently independent of the government, the inquiry should have an international component. Finally, Ethiopia’s international development partners should also reassess their development programming in Oromia to ensure that aid is not being used – directly, indirectly or inadvertently – to facilitate the forced displacement of populations in violation of Ethiopian and international law.

Recommendations

To the Government of Ethiopia

Excessive Use of Force Against Protesters

- Support a credible, independent and transparent investigation into the use of excessive force by security forces. The inquiry should include a full accounting of the dead and injured, the circumstances surrounding each incident resulting in death or injury, the extent to which government security forces were implicated in human rights violations.

- Discipline or prosecute as appropriate all members of the security forces, regardless of rank or position, responsible for using excessive force against protesters.

- Consistent with the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, law enforcement and security agencies should issue clear orders to their personnel that any use of force must be strictly necessary and proportionate to a real and imminent threat, and that use of excessive force will be punished. Lethal use of firearms may only be made when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life. Law enforcement officials who carry firearms should be authorized to do so only upon completion of special training in their use. Training of law enforcement officials should give special attention to alternatives to the use of force and firearms, with a view to limiting their use.

Arbitrary Detention

- Promptly release from custody those individuals who have not been charged or were charged for the peaceful exercise of their fundamental rights, including freedom of expression, association, and assembly.

- Cease detaining civilians in military camps and barracks and ensure that all individuals are detained in official detention facilities.

Enforced Disappearances

- Promptly report to families the name, location and other pertinent information of all individuals taken into custody.

- All authorities who have received inquiries from families of people who are missing or believed forcibly disappeared should reply promptly, providing all known information on the whereabouts and fate of these individuals and on steps being taken to acquire such information if not readily available.

- All those forcibly disappeared should be immediately released or brought before a judge and charged with a legally recognizable offense.

- Ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

Treatment in Detention

- Ensure that all prisoners are treated in accordance with the revised Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Mandela Rules).

- Promptly, transparently, and impartially investigate all allegations of torture or ill-treatment in detention and ensure that all personnel implicated in abuse, regardless of rank, are appropriately disciplined or prosecuted.

- Publicly and unequivocally condemn the practice of torture and other forms of mistreatment in detention making clear that there is never a justifiable reason for mistreatment, including extracting confessions, retribution for alleged support of banned groups, or other punishment.

- Significantly improve legal safeguards at places of detention, including ensuring the right to access a lawyer from the outset of a detention, presence of legal counsel during all interrogations, and prompt access to family members and medical personnel. Close all detention facilities that do not meet international standards.

- Ensure that the federal police, military, regional police, public prosecutors, and other law enforcement personnel receive appropriate training on interrogation practices that adhere to international human rights standards.

- Take all necessary steps to end incommunicado detention and prolonged solitary confinement at detention facilities.

- Allow independent oversight of all detention facilities and prisons by providing access for international humanitarian and human rights organizations and for diplomats to engage in unhindered monitoring of conditions and private communications with all prisoners.

- Ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

Freedom of Expression

- Eliminate restrictions on the right to freedom of movement of domestic and foreign journalists throughout Ethiopia, including in areas where serious human rights abuses are allegedly occurring. Instruct police and security personnel to permit freedom of movement of the media.

- Cease blocking and censoring of social media sites and websites of political parties, media, and bloggers, and publicly commit not to block such websites in the future.

- Cease jamming radio and television stations and publicly commit not to jam radio and television stations in the future.

Abuses Related to Development Programs

- Engage in open and transparent consultations with communities affected by development programs, particularly when programs could result in displacement from land affected by the Addis Ababa Integrated Development Master Plan.

- Ensure that displaced communities have adequate redress, preferably by restitution or if not possible, just, fair, and equitable compensation for the lands, territories, and resources that they have traditionally owned or otherwise occupied or used.

To the Ethiopian Judiciary

- Ensure that statements, confessions, and other information obtained through torture or other ill-treatment are not admitted as evidence. In cases of a claim that evidence was obtained through coercion, the authorities must provide in court information about the circumstances in which such evidence was obtained to allow an assessment of the allegations.

- Ensure that complaints of torture and ill-treatment in detention are promptly investigated and that detainees who bring complaints about mistreatment in detention are protected from reprisals.

To the United Nations Human Rights Council:

- Press Ethiopia to immediately end the use of excessive force against protesters and related human rights abuses, and to hold accountable those responsible for killings and other abuses in connection with the protests.

- Press for the release of all protesters, opposition politicians, journalists and others arbitrarily detained during the time of the protest and prosecuted under the criminal code or anti-terrorism law.

- Urge Ethiopian officials to invite relevant UN human rights mechanisms, including the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to visit Ethiopia.

- Support a credible, independent and transparent investigation into the use of excessive force by security forces. The inquiry should include a full accounting of the dead and injured, the circumstances surrounding each incident resulting in death or injury, the extent to which government security forces were implicated in human rights violations.

To Ethiopia’s International Partners:

- All concerned governments should press Ethiopia to immediately end the use of excessive force against protesters and related human rights abuses, and to hold accountable those responsible for killings and other abuses in connection with the protests.

- Support a credible, independent and transparent investigation into the use of excessive force by security forces. The inquiry should include a full accounting of the dead and injured, the circumstances surrounding each incident resulting in death or injury, the extent to which government security forces were implicated in human rights violations.

- Publicly call and privately press for the release of all protesters, opposition politicians, journalists and others arbitrarily detained during the time of the protest and prosecuted under the criminal code or anti-terrorism law.

- Donors that fund programs with the federal police, regional police or military should carry out thorough investigations into allegations of human rights violations by security forces during protests and within places of detention to ensure their funding is not contributing to human rights violations.

- Improve and increase monitoring of trials of protesters and others arrested for exercising their basic rights to ensure trials meet international fair trial standards.

- Publicly and privately raise concerns with Ethiopian government officials at all levels regarding torture, ill-treatment, and other human rights violations in detention facilities in Ethiopia.

- Actively seek unhindered access to detention facilities for international humanitarian and human rights organizations and for diplomats to monitor the conditions of arbitrarily detained protesters, opposition politicians, and journalists.

- Publicly and privately raise with government officials concerns about freedom of assembly and expression and how violations of these rights may undermine development and security priorities.

- Ensure that no form of support, whether direct or indirect financial, diplomatic, or technical, is used to assist in investment projects within the area of the Addis Ababa Integrated Development Master Plan that have the potential for displacement until the government investigates human rights abuses linked to the process and takes appropriate measures to prevent future abuses.

- Urge Ethiopian officials to invite relevant UN and AU human rights mechanisms, including the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to visit Ethiopia.

To the Authorities in Kenya, Sudan, Egypt, Djibouti, Somaliland and Somalia

- Ensure that individuals fleeing the crackdown and requesting asylum can do so quickly and effectively, and that they receive prompt processing of their applications and protection from targeted threats.

To Potential Investors

Potential investors should ensure that:

- Local communities, farmers, and pastoralists have been fully consulted and that fair compensation is provided by the government, as per Ethiopian law, to any owners or customary users of land who are displaced.

- Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) have been carried out that identify potential impacts and strategies to mitigate these impacts. These EIAs should be available publicly and to impacted communities.

Methodology

This report documents the most significant patterns of human rights violations during the Oromo protests between November 2015 and May 2016, and is based on research conducted during this period in Ethiopia and East Africa. Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed more than 125 individuals from 62 locations across Oromia’s 17 zones and three “special zones.” Interviewees included victims, witnesses and government officials in Oromia, media professionals, and former government and intelligence officials. All were interviewed individually in person, via telephone, or another secure method of communication. Those interviewed had a wide range of backgrounds from diverse geographic areas, ages, gender, livelihoods, and political affiliations, to provide as broad a perspective as possible.

Ten different translators in five locations helped to interpret from Afan Oromo or Amharic into English where necessary. No one interviewed for this report was offered any form of compensation. All interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interview and its voluntary nature, including their right to stop the interview at any point, and gave informed consent to be interviewed.

Human Rights Watch also consulted court documents, photos, videos and various secondary material, including academic articles and reports from nongovernmental organizations, and information collected by other credible experts and independent human rights investigators that corroborate details or patterns of abuse described in the report. Human Rights Watch took various precautions to verify the credibility of interviewees’ statements. All the information published in this report was based on at least two and usually more than two independent sources, including both interviews and secondary material.

This report is not a comprehensive investigation of the human rights abuses associated with the 2015-2016 protests in Oromia. The Ethiopian government’s restrictions on access for independent investigators and hostility towards human rights research make it difficult to corroborate details of the many incidents that have occurred across a wide geographic area. It is also challenging to verify government claims of violence by protesters.

Human Rights Watch conducted some research for this report inside Ethiopia, but some victims of abuses were interviewed outside the country, where they were able to speak openly about their experiences. Ethiopian government repression makes it difficult to assure the safety and confidentiality of victims of human rights violations. The government frequently tries to identify victims and witnesses providing information to the media or human rights groups. The authorities have harassed and detained individuals for providing information or meeting with international human rights investigators, journalists, and others.

Even after individuals flee Ethiopia, their family members who remain may be at risk of reprisals. Ethnic Oromos fleeing the crackdown also face significant challenges finding security and protection in neighboring countries and regions such as Djibouti, Egypt, Puntland, Kenya, Somaliland and Sudan.

Given concerns for their protection and the possibility of reprisals against family members, interviewees have been assigned pseudonyms. Locations of interviews and key identifying information has been withheld.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the government of Ethiopia on May 24, 2016 to share the findings of this report and to request input on those findings. We also requested information regarding steps that the government may have taken to carry out investigations or discipline security forces but we did not receive any response at time of writing. Human Rights Watch staff shared previous findings and reports on the Oromia protests with officials at the Ethiopian Embassy in Washington, DC.

Abbreviations

|

EHRP EFFORT EIA EPRDF HRCO ITU OFC OLF OMN OPDO TPLF |

Ethiopia Human Rights Project Endowment Fund for the Rehabilitation of Tigray Environmental Impact Assessments Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front Human Rights Council Ethiopia International Telecommunications Union Oromo Federalist Congress Oromo Liberation Front Oromia Media Network Oromo People’s Democratic Organization Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front |

I. Background

On November 12, 2015, authorities began clearing a forest and football field for an investment project in Ginchi, a small town in Oromia, Ethiopia’s largest region, about 80 kilometers southwest of the capital, Addis Ababa.[1] The move sparked student protests in Ginchi, in turn triggering a wave of demonstrations across Oromia. Since mid-November there have been at least 500 known incidents of protests involving students, farmers and others, mostly in Oromia but also in other locations with large populations of Oromo ethnicity.[2]

As with previous protests in Oromia in 2014, many protesters raised concerns over the Addis Ababa Integrated Development Master Plan (“the Master Plan”), a proposed 20-fold expansion of the municipal boundary of Addis Ababa, surrounded by Oromia Regional state.[3]

Protesters fear the expansion will further displace Oromo farmers without consultation or adequate compensation. Addis Ababa has already experienced significant growth over the past 10 years, resulting in significant displacement of Oromo farmers from land around the city. On the rare occasions that authorities have provided compensation, the funds are usually inadequate to make up for lost livelihoods and farmers rarely receive alternate land. There is little recourse for the losses in courts or other institutions.

Protesters also expressed concerns that implementation of the Master Plan would split east and west Oromia because the new municipality would no longer be administered by Oromia Regional State. Some protesters feared this could affect regional government budgets, Oromo education, and Afan Oromo language resources in school and government offices within the new Addis Ababa municipality.

Many protesters also raised grievances and cited abuses related to local business and development projects including flower farms, mining activities and light manufacturing development. For example, protests in Guji zone raised concerns about gold and tantalum mining in Shakiso, and protests in Mirab Welega zone referenced marble quarries near Mendi.[4] While grievances vary depending on the project and area, some common concerns include displacement, environmental degradation and impact on the water supply of dangerous and largely unregulated chemicals, failure to hire local labor, and real or potential tensions due to migration of laborers from other parts of Ethiopia.[5]

As the protests continued into December and early 2016, protesters also increasingly voiced anger and frustration at the brutal response of the security forces to the protests – the killings and mass arrest of protesters and the suppression of Oromo associations and political parties. The protests also draw on decades of deeply held grievances within Oromo communities who feel they have been politically, economically and culturally marginalized by successive governments in Ethiopia.[6]

Patterns of repression and control in Oromia

Oromia is home to many of Ethiopia’s estimated 35 million ethnic Oromo, the country’s largest ethnic group.[7] Ethnic Oromo who express dissent are often arrested and tortured or otherwise ill-treated in detention, often accused of belonging to or being sympathetic to the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF). The OLF is an armed insurgent group designated a terrorist organization by Ethiopia’s parliament in 2011. The group has waged a limited armed struggle with minimal military capacity according to many analysts.[8] Government officials often cite OLF presence, activities, and links to justify acts of repression of Oromo individuals. Tens of thousands of Oromo individuals have been targeted for arbitrary detention, torture and other abuses even when there is no evidence linking them to the OLF.[9]

Abuses against individuals of Oromo ethnicity occur within a broader pattern of repression of dissenting or opposition voices in Ethiopia. Countrywide, there are few opportunities for citizens to express critical or dissenting views. Independent media and civil society have been decimated since controversial elections in 2005 and the passage of two draconian laws in 2009.[10] Those who speak out – particularly those who criticize government development programs – are regularly described as “anti-peace” or anti-development and face harassment or arrest and then politically motivated prosecutions. Ethiopia’s electoral environment provides little opportunity for opposition voices in Oromia or elsewhere: the ruling party won 100 percent of parliamentary seats at both federal and regional levels in the May 2015 federal elections, a telling reflection of the atmosphere of intimidation.[11]

Membership in the ruling coalition’s Oromia affiliate, the Oromo People’s Democratic Organization (OPDO), is often a requirement for employment or for upward mobility within government, which is by far the largest employer in Oromia. Ordinary citizens in Oromia and other states say that loyalty to the ruling party is required to guarantee access to seeds, fertilizers, agricultural inputs, food aid and many of the benefits of development.[12] Telephone surveillance is commonplace and a grassroots system of community monitoring and surveillance, commonly called “one to five” or “five to one,” is in place in many parts of Ethiopia, including large swathes of Oromia.[13]

Independent civil society groups and associations are severely restricted and members report regular harassment.[14] Historic and contemporary suppression of Oromo institutions, civil society and political parties make it difficult for the government to negotiate with any particular group to find a lasting solution to the grievances. As a result, protests flare up in Oromia on a cyclical basis.[15] For instance in 2004 the planned relocation of the regional capital from Addis Ababa to Adama generated demonstrations,[16] as did concerns over perceived government interference in the religious affairs of Muslim communities between 2011-2014,[17] and the first round of protests over the Master Plan in 2014.

The 2014 protests – which were smaller and more localized – were in other ways a precursor to the events of 2015-2016. Between April and June 2014 security forces dispersed students and others protesting the Master Plan in a number of cities using teargas and live ammunition, killing at least several dozen people and arresting several thousand, including hundreds of members of the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC).[18] Many remain in custody without charge at time of writing. Most of the approximately 30 individuals that Human Rights Watch interviewed who were victims or witnesses of the 2014 protests alleged torture and other ill-treatment in detention. Some former detainees have not been permitted to return to their universities or schools, and claimed they were released on the condition that they do not participate in further protests. There was no known government investigation into the use of excessive and lethal force during the 2014 protests or the grievances driving the protests.[19]

Displacement Linked to Economic DevelopmentEthiopia is experiencing an economic boom and the government has ambitious plans for further economic growth.[20]Access to land and natural resources, including water, will be required to sustain this growth. Since 2009, Ethiopia has leased vast portions of land to foreign and domestic investors, particularly in lowland areas, like Gambella and Benishangul-Gumuz that have relatively low population density and often ample water supplies.[21] Recent government efforts to market lands for investment opportunities have included the water intensive sugar and cotton industries.[22] Mineral deposits are also being developed in Oromia, the Afar region and elsewhere.[23]There is little evidence of environmental assessments being carried out for any of these developments and little or no assessment of the water needs or requirements for downstream users. Around Addis Ababa, a growing middle class has created increased demand for residential, commercial, and industrial properties, accompanied by reports of displacement of farmers without adequate consultation or compensation. Many protesters view the Master Plan as sanctioning through government policy the displacement that has already been occurring around Addis Ababa for years. Some proponents of the plan have argued that since Addis Ababa will grow with or without a plan, the plan would facilitate development in a more organized manner, potentially reducing the negative impact of displacement and improving consultation, compensation and the provision of alternative livelihoods. |

Government Response to the Protests

During the first weeks of the protests in November and December 2015, the Oromia regional security forces mainly responded to the protests, with the assistance of the federal police in some locations.[24] They regularly arrested and beat protesters, many of whom were primary and secondary school students, and there were some reports of live ammunition being used.[25]

In mid-December the response from security forces shifted and escalated dramatically following Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn’s December 16 statement that the government “will take merciless legitimate action against any force bent on destabilizing the area.”[26] On the same day that the prime minister released his statement, the director general of communications, Getachew Reda saidthat “an organized and armed terrorist force aiming to create havoc and chaos has begun murdering model farmers, public leaders and other ethnic groups residing in the region.”[27]The government then deployed military forces throughout Oromia and have subsequently responded to the protests with a military operation. Wako, a 17-year-old student from West Shewa, said the response of the security forces changed markedly between two different protests in November:

During the first protest [in mid-November], the Oromia police tried to convince us to go home. We refused so they broke it up with teargas and arrested many. Several days later we had another protest. This time the [federal police] had arrived. They fired many bullets into the air. When people did not disperse they fired teargas, and then in the confusion we heard the sounds of more bullets and students started falling next to me. My friend [name withheld] was killed by a bullet. He wasn’t targeted, they were just shooting randomly into the crowd.[28]

On January 12, 2016, the OPDO announced on state television that the Master Plan would be cancelled. Such a policy reversal was unprecedented but many Oromo have been skeptical given general distrust, a history of broken government promises, and continued brutality and arrests by security forces. A university student told Human Rights Watch: “Those announcements are for the outside world. It means nothing when the soldiers keep shooting us in the street, torturing us in the jails, and the government keeps throwing out our farmers.”[29]

Human Rights Watch was not able to identify any tangible change in the response of the security forces following the revocation of the Master Plan. Security forces continued to treat the protests as a military operation and use unnecessary and excessive force. There were several egregious incidents around the time of the Master Plan cancellation, with at least 12 protesters killed between January 17 and 20, 2016 in Mieso, Sodoma and Chinaksen in Hararghe zone by the Somali Regional State’s notorious Liyu police.[30]

II. Violations by Security Forces

I’ve lived here for my whole life, and I’ve never seen such a brutal crackdown. There are regular arrests and killings of our people, but every family here has had at least one child arrested. One family of seven who live near me are all in detention. This generation is being decimated in this town. All the young people are arrested and our farmers are being harassed or arrested. For me, my four sons have all disappeared, my [12-year-old] daughter is too afraid to go back to school, and I fear being arrested at any moment.[31]

–Yoseph, farmer, 52, from West Wollega zone, January 2016

Security forces committed numerous human rights violations in response to the protests, including arbitrary arrest and detention, killings and other uses of excessive force, torture and ill-treatment in detention, and enforced disappearances. Human Rights Watch believes that at least 400 people have been killed, unknown numbers have been forcibly disappeared, thousands injured, and tens of thousands arrested. While many were released, an unknown number of people remain in detention without charge. Many of the released detainees described torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment in detention. Many of those killed, injured, or arrested were students. An unknown number – likely thousands – are internally displaced, and thousands more have fled the country.[32] Precise numbers are unknown given limitations on access and independent reporting.

Lencho, a 16-year-old Grade 5 student from near Shashemene, described the protest that started in his school in late December:

We were angry about the Master Plan and about students being killed by the soldiers [elsewhere in Oromia], so we decided that the next day we were to join other schools to protest. That next morning we all marched chanting to end the “Master Plan.” We were a small group of maybe 50. We met three other groups of protesters from other schools, and the crowd was large. We were marching to the center of town, chanting slogans about the plan and to release students from prison. Once we were close to the center of town, we met a wall of police and soldiers. As soon as we saw them, they fired teargas. I didn’t know what it was at first. Then I heard students screaming, some students were running away, but many were on the ground, and the police were beating them with rubber sticks. Others were grabbing students and leading them away or throwing them in the back of trucks. I could see this because I was far enough back that the police hadn’t got to us yet. [33]

Human Rights Watch documented a similar pattern of security force response in most of the 62 protests Human Rights Watch documented. In most locations, federal police and military lead the response. In three locations protesters reported that security forces tried to persuade them to disperse before firing teargas. In almost all locations, the security forces fired teargas to disperse students and began beating those who did not leave with wooden and rubber sticks, and occasionally whips. Hundreds of protesters reportedly suffered broken limbs from beatings.

Moti, an 18-year-old from East Hararghe zone, said:

We were walking, demanding an end to the use of force and against the Master plan, then we saw the police. Minutes later there was smoke and it started burning our eyes and throats, then I remember being hit with a stick on my arms. Then I ran away. I went to the clinic the next day because they had broken my wrist.[34]

In some places students were injured by other panicked protesters who trampled them when teargas was fired. Hirba from near Ambo said, “It all happened quickly. Students who were tear-gassed or were injured after being hit by the police were then run over by students trying to get away. My friend broke his arm and another broke a rib because students ran over them to get away.”[35]

In many locations, injured students were either carried off by other protesters or taken away by security forces to unknown locations.

Lencho described what happened after police failed to break up protests with teargas:

Then there was another wave of older students who came later and were very angry, particularly when they [police] started taking away students. When those students marched forward, you could hear bursts of gunfire. I didn’t know what it was at first, I thought it was just more teargas, but then I saw people falling down. I saw the soldiers shooting into the crowd of students. That is when I ran away. I learned later that three people had been shot, and one died.[36]

Human Rights Watch found that security forces used live ammunition in about half of the protests we documented, and apparently used few deterrent measures other than teargas before using live ammunition. In several instances, protesters said soldiers first fired in the air to try and disperse protesters. When that did not disperse the crowds quickly, the federal police or military fired bullets indiscriminately into the crowd. There is no indication that the shootings were targeted at specific individuals in any of these locations. Nuru, a 20-year-old protester in East Hararghe, said:

It all happened very quickly. Just when we realized teargas was thrown, then we heard bullets and everyone screaming, and people running around – students, police. The only ones who didn’t seem to be running around were the soldiers who were shooting into the crowd. They were maybe [35 meters away].[37]

After the protests ended, security forces conducted mass arrests in almost all locations – usually the evening of the protest. Witnesses said security forces went door-to-door looking for students who had participated, and continued to arrest people in the days and weeks following the protest. Many described the scale of the arrests and violence by security forces as unprecedented in their memory.

Summary Killings and Use of Lethal Force During Protests

Human Rights Watch documented 27 killings by security forces in the 62 protest locations we investigated. We received additional vague or uncorroborated information from dozens of other sources about cases of killings. There are also reports of approximately 400 killings from other sources that have investigated, including the nongovernmental Human Rights Council Ethiopia (HRCO), Ethiopia Human Rights Project (EHRP) and other independent activists and investigators. Specific details on killings are provided in Annex 1.

Under international human rights law, law enforcement officials may use only such force as is necessary and proportionate to maintain public order, and may only intentionally use lethal force if strictly necessary to protect human life or in self-defense.[38] Although some protesters reportedly threw stones at police and destroyed property in some locations, such acts of criminal damage do not justify intentional use of lethal force. International standards also require that governments ensure arbitrary or abusive use of force and firearms by law enforcement officials is punished as a criminal offense.[39]

Four high school students from Arsi who were interviewed separately described the killing of a 17-year-old fellow student. Waysira, 17, said:

We heard a Grade 6 student was killed in [neighboring village]. To show our solidarity we decided to protest. When the different classes came together and started marching toward the government office, security forces moved toward us. They threw teargas, and then we heard the sound of gunfire. My friend [name withheld] was shot in the chest, I saw him go down and bleeding. We ran away and I never looked back. His mother told me later he had been killed.[40]

Another student described the scene in Bedeno in East Hararghe zone in January, 2016, when security forces shot at least six students:

My friend [name withheld] was shot in the stomach [at the protest], his intestines were coming out, he said, “Please brother, tie my [wound] with your clothes.” I was scared, I froze and then tried to do that but I was grabbed and arrested by the federal police. Jamal died. They arrested me and took me to Bedeno police station.[41]

The number of killings during protests appears to have increased in the middle of December and in mid-late February. Large numbers of protesters were killed in West Shewa zone (particularly Ambo), Southwest Shewa Zone (particularly Waliso), Dilla town in Gedeo zone of SNNPR state, and Shakiso town in Guji zone. There were many killings reported in East and West Hararghe zones in January and February, some of which involved the Somali Regional State’s notorious Liyu police. Generally it was the military that used live ammunition against protesters, where military forces were deployed.

Security forces also killed students, including children, when they went house-to-house searching for protesters in the evenings after protests. Security forces killed some students when they tried to flee from arrest and others died in unknown circumstances in scuffles during arrests. The exact circumstances of many deaths are unknown. Witnesses and family members described killings at night in Waliso, Dembidolo, and Ambo towns. People said they heard bursts of gunfire at night in many locations but did not always witness the killings. One man described his younger brother’s death in West Shewa zone:

[After the protest] I hid away from home, but my 16-year-brother hid at home. According to the neighbor, when they [security forces] arrived he ran and they chased him out back and they shot into the dark. The next morning they found his body with a bullet in the back of the neck.[42]

Security forces also killed students at schools and other locations when they tried to prevent future demonstrations. Gameda, a 17-year-old Grade 9 student near Shashemene, described security forces entering his school compound in mid-December:

We had planned to protest. At 8 a.m., Oromia police came into the school compound. They arrested four students [from Grades 9-11]. The rest of us were angry and started chanting against the police. Somebody threw a stone at the police and they quickly left and came back an hour later with the federal police. They walked into the compound and shot three students at point-blank range. They were hit in the face and were dead. They took the bodies away. They held us in our classrooms for the rest of the morning, and then at noon they came in and took about 20 of us including me.[43]

Some people said they heard single bullets fired at night, including in Waliso town and Jeldu woreda, raising concerns of extrajudicial executions. In Waliso and Jeldu there were also credible reports of individuals being killed in unknown circumstances, although details of death are unknown, making it difficult to ascribe the deaths to the single gunshots.[44]

In addition to killings, dozens of students and other protesters received bullet wounds, some in the back, and many in the lower body. Many of those injured and killed were under age 18. This may have been because students were often at the front of the protests because, as one 28-year-old protester put it, “They are eager and have not been through this before.”[45]

Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions

Ethiopian security forces have arrested tens of thousands of protesters, students, farmers, OFC members and intellectuals since the protests began in mid-November.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) prohibits arbitrary arrest and detention.[46] The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention says that deprivation of liberty is arbitrary “[w]hen it is clearly impossible to invoke any legal basis justifying the deprivation of liberty” or the basis for detention is a violation of basic rights.[47]It is not enough to follow the procedures of the law, such as issuing formal but unsubstantiated charges: as the UN Human Rights Committee has explained, “arbitrariness” is not to be equated with “against the law,” but must be interpreted more broadly to include elements of inappropriateness, injustice, lack of predictability and due process of law.”[48]

The security forces have frequently carried out mass arrests, without regard to any unlawful action by individuals. Students described many classmates being arrested or fleeing their communities in fear. A Grade 8 student at a school in Arsi said that of the 28 people in her class, only four were left: 12 were arrested and their whereabouts are unknown, three were arrested and released, four fled the community, one was killed by bullet, two were injured, and the whereabouts of two others were not known. Their teacher had also been arrested. Class was no longer taking place.[49]

Authorities have detained people in police stations, prisons, military camps, and other unofficial, unknown places. In many locations, children were detained with adults in violation of international law.[50] Several students told Human Rights Watch that government offices or classrooms were being used as makeshift detention centers, but Human Rights Watch was not able to verify these allegations. People detained for longer than several weeks were often relocated to larger detention centers or military camps. Often they did not know where they had been detained until they were released. Some of the military camps are well known and have histories of mistreatment, including Sanakle, near Ambo town; Ganale, near Dodola town in Mirab Arsi zone; Urso in Hararghe; Adele in Hararghe; and Taraloch, while others were previously unknown.

Human Rights Watch learned of large transfers of prisoners from local places of detention to larger military camps between March 19-21, 2016, including Urso military camp. Due to lack of access, Human Rights Watch was not able to corroborate these claims. Typically, prisoners in military camps are more vulnerable to torture, are detained for longer periods of time, and lack access to lawyers, relatives or any form of judicial review.[51]

Arrests During Protests

Arrests often follow a similar pattern during the protests. Oromia police, federal police and occasionally the military would arrest students during the protests, usually after throwing teargas canisters. Where Oromia or Somali Region Special (“Liyu”) Police were involved, they also made arrests. Arrests at protests were usually not targeted – security forces would arrest whomever they could and then take them to the nearest detention facility, witnesses said. Most detainees spent several weeks in detention and were then released without charge. Human Rights Watch documented arrests at all 62 protest locations we investigated.

There have been a few small protests in Addis Ababa. Security forces arrested 20 Addis Ababa University students following a peaceful March 8 demonstration in front of the United States embassy. The students were charged under the Criminal Code and Peaceful Demonstration and Public Political Meeting Procedure Proclamation on charges of “inciting the public through false rumors.” The charge sheet alleges that students:

…collectively protested while holding messages written in Amharic, English and Afan Oromo which says “Schools should be for knowledge not for military camp”; “Stop mass killing Oromos”; “Government should pull out its military force from Oromia”; “Ethiopian military force is terrorizing Oromo people”; “Government should not give land for the investors while the people are starving”; and, “American government should see Ethiopian false democracy.” These messages could mislead the public opinion.[52]

The students face up to three years in prison if convicted.[53]

Outside of urban areas like Addis Ababa, Jimma, Adama, and Ambo, very few of the 46 former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch were brought before a judge and none had access to a lawyer.

Arrests After Protests

Security forces regularly conducted door-to-door raids and arrests in the evenings after protests. Human Rights Watch documented arrests of this type in all of Oromia’s 17 zones and three “special zones.” Young students – generally boys – were typically targeted. The youngest student reportedly arrested was a 6-year-old girl detained in Borana zone.[54] Different branches of the security forces went door-to-door together looking for students. A 17-year-old student from Arsi zone said:

This was our third day of protesting. We knew the pattern. During the protest they would arrest who they could, but at night they would go door-to-door arresting students. If they couldn’t arrest those they wanted, they would arrest our parents. So we would all run to the rural areas and hide and just hope that when we came back our parents had not been arrested.[55]

Security officials sometimes arrested family members in order to pressure students, a form of collective punishment. Human Rights Watch documented 10 cases in which parents or spouses of wanted students were arrested in order to persuade those students to turn themselves in to authorities. Human Rights Watch and others have documented similar tactics in Oromia in the past.[56]

Security officials also arrested those suspected of hiding protesters in their homes. Lelisa, a woman who assisted students fleeing the security forces in Arsi in early December, said:

I wasn’t at the protests but I heard gunfire all day long and into the night. Students were running away and hiding themselves. Ten students came to me and asked for help so I hid them from the police. The police were going door-to-door at night arresting students. They came to my house, arrested all the boys and I convinced them that the three girls were my daughters. Then an hour later they came back and arrested my husband. They beat him in front of me, when I begged them not to kill him they kicked me and hit me with the butt of their gun. They took him away. I have heard nothing from him since.[57]

Arrests at Schools and Universities

Human Rights Watch documented four cases where security forces arrested students or teachers in their classrooms to prevent students from protesting or to deter future protests. Midasa, an 18-year-old Grade 7 student from Hidilola in Borana zone said:

It was the second day of the first round of protests in Hidilola. The police came to our school and wouldn’t let anyone leave. We were all called into the courtyard and all our names were read out to see who was there. After your name was called out if you were present you were told to go to the classroom or the principal’s office – if you were sent there [the principal’s office], you were taken to jail. I went to the classroom. The teacher was telling us if anyone protested they would be expelled from school, and then the same police came in and started just randomly grabbing and hitting students. I went home and was told police had also gone door to door and told parents if students protested the parents would be arrested.[58]

Soldiers or federal police frequently stormed university dormitories and arrested Oromo students. Human Rights Watch documented arrests in Ambo, Adama, Jimma, Haramaya and other university dormitories. The selection of students seemed arbitrary in some cases but in other situations the security officers read out the names of selected students. In Jimma in December, students were asked to identify those who were Oromo and students of other ethnicities were told to leave the dormitory. Security forces then violently beat the Oromo students and arrested many that evening.[59]

In some universities, the police or military occupied the campus and restricted students from leaving to prevent them from protesting. At Ambo University, which was a key site of the 2014 protests,[60] students protested the continued occupation of the campus by security forces in late December and demanded the military stop beating, harassing and arresting students. They repeatedly raised concerns with the university’s president. Gudina, a 23-year-old engineering student said:

He [the university president] called all the students and asked them to stop demonstrations. He did not listen to the student [demands] but he said… [the] military officers are here to stay, they will not leave. Shortly after he left and some of the students started to leave the university and go home then the military officers attacked us. They started beating the students with rubber sticks. They started kicking and punching students mercilessly. I was one of the students gathered by the military outside one of the blocks. The officers asked us to lie down with our faces on the ground. Then they stared beating us on the back with sticks.[61]

Gudina was detained for three weeks. Another student, describing the same incident, said, “They were beating us like animals…They asked us to walk on our knees and my knees are still hurting.”[62]

Kadir, a student at Rift Valley University in Waliso, described security forces storming the classrooms:

Students would run in all directions, it was like a war zone. One student was shot and killed while trying to run away. On 10 separate occasions they came into the classroom. Sometimes they would try to prevent us from leaving the classroom to protest, other times they would come and arrest students at random.[63]

Arrests of influential community leaders, opposition leaders, government officials and artists

In the days and weeks following the protests, security officials arrested scores of individuals deemed to be influential or prominent in their communities, or those with a history of past problems with the government or security forces. Within schools, these individuals included student association leaders, cultural club leaders, older students, and prominent teachers. Artists, opposition political party supporters, individuals with perceived family ties with the OLF, business owners, people involved in promoting Oromo art and culture, and even influential local government officials were also arrested. >[64]

Several OPDO officials in woreda governments told Human Rights Watch that the lists of those targeted were often compiled by local security officials, administration officers, and even school administrators.[65]

Human Rights Watch found that individuals who had previously been involved in the 2014 protests were at particular risk. Many had been released on the condition that they do not participate in future protests. They were arrested as soon as the current round of protests began.

High-profile politicians were also targeted. On December 23, 2015, security forces arrested Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC) Deputy Chairman Bekele Gerba at his home and took him to Addis Ababa’s Maekelawi prison.[66] He was arrested with 22 other OFC officials, including OFC legal counsel Dejene Tafa. They were charged under the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation at the Federal High Court 19th criminal bench on April 22, 2016.[67] According to family members, it has been difficult to find a lawyer who is willing to defend them, highlighting the level of fear within the legal profession when it comes to defending high-profile opposition politicians. Bekele has been a staunch advocate for non-violence and a moderate voice in Ethiopian politics in an increasingly polarized political environment.[68]

Music, one of the few mediums the government has been unable to censor or control, has played an important role in mobilizing students and raising awareness of Oromo rights. Jamal, an 18-year-old student from Adaba woreda in West Arsi zone, described being searched every morning at school for one week by the military. “They were searching for those that had Oromo music on their phones,” he said. “They arrested six people that had protests songs on their phone, songs by Caalaa Bultum,[69] Ebisa Adunya,[70] and Kadir Martu.”[71] The whereabouts of those six students are not known.[72] Several well-known Oromo musicians have also been arrested.

An Ethiopian intelligence official confirmed to Human Rights Watch that targeting public figures was deliberate government policy. He said, “It is important to target respected Oromos. Anyone that has the ability to mobilize Oromos will be targeted, from the highest level like Bekele, to teachers, respected students, and Oromo artists.”[73]

A local woreda official told Human Rights Watch:

When the protests were happening in other parts of our [zone], we were told to round up all those that might want to protest – our list included the best students, those who were involved in any language or cultural clubs, teachers who had not shown their loyalty to government, several well-known business owners, and past troublemakers. We were to stop this protest but also to prevent future problems by arresting those who were not close to us [government]. They were all arrested or ran away, but the protests happened anyway. I was then blamed, and heard I was to be arrested so I ran away too.[74]

Even local government officials were fired or arrested in many locations and accused of mobilizing protesters, being overly sympathetic, or failing to control the protesters.[75] Targeting of government officials increased in March and April of 2016. Six local government officials told Human Rights Watch that they were already under suspicion because of their perceived support for OFC and because some refused to join the OPDO. Three of the officials were told to go and spy on students to determine who was behind the protests in order to show their loyalty. Eba, a woreda government official, said:

I was to go and mingle with three nearby villages and find out who was encouraging students to protest. I refused. Then they made a false allegation that I was the one who was mobilizing. They fired me. Many officials in the woreda lost their jobs, and it was those that refused to carry out such duties that lost their jobs. When the protests did start after that, I was to be arrested. Since I wasn’t home, they arrested my brother. He hasn’t been seen since.[76]

Enforced Disappearances

Hundreds of individuals remain unaccounted for and dozens of parents told Human Rights Watch that they do not know the whereabouts of their children since they were arrested by the authorities. Six parents told Human Rights Watch that they had asked at the local security office or police station and security officials denied their children were in custody. In each of these cases, witnesses had informed the parents that their children had been arrested at or after the protests.

Such cases appear to be enforced disappearances under international law. An enforced disappearance is defined under international law as the arrest or detention of a person by state officials or their agents followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty, or to reveal the person’s fate or whereabouts.[77] “Disappeared” people are often at high risk of torture, a risk even greater when they are detained outside of formal detention facilities. In addition to the harm done to the person, enforced disappearances cause continued suffering for family members.

Enforced disappearance violates a range of fundamental human rights protected under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Ethiopia is a party, including prohibitions against arbitrary arrest and detention; torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment; and extrajudicial execution.

The mother of a missing 15-year-old student from the Borana zone said:

He went to school in the morning. They had planned to protest. He told me he wouldn’t but I knew he would. That was the last time I heard from him. …Others told me he was arrested by federal security. But I went to the police station, to the local security office and no one had any information about him. I talked to some boys who were arrested at the protest and had been taken to the local police station, and they said they had heard he was taken to a military camp somewhere but they weren’t sure.[78]

Parents told Human Rights Watch that it was risky to inquire at local detention facilities about their children’s whereabouts. A mother trying to find information about her 17-year-old son, who had been arrested and taken to Torolach military camp, said: “I went to the camp to find out why they had arrested him and they detained me for one week. Then my husband came to see us in the camp and they arrested him too.”[79]

Torture, Ill-Treatment, and Sexual Assault in Detention

Mistreatment in detention is common and there have been numerous credible reports of torture, particularly from those who have been detained before. Most of the 46 interviewees who had been detained during the protests said that they were beaten in detention, sometimes severely. At least six of the beaten detainees were under age 18. Security forces used wooden sticks, rubber truncheons, or whips to beat people. Several students said they were hung up by their wrists and whipped. Four students said they were given electric shocks on their feet and two described having weights tied to their testicles. These torture techniques match established patterns of torture in Oromia.[80]

International law prohibits torture – the authorities’ infliction of severe pain or suffering to obtain information or a confession – and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Governments are obligated to investigate and prosecute torture and other ill-treatment by government officials and agents. Statement made as a result of torture shall not be invoked as evidence in court, except against a person accused of torture.[81]

All of the former detainees who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that the authorities accused them of mobilizing students to join the protests and interrogated them about why students were protesting and who was mobilizing and organizing them. Federal police, military personnel or people in civilian clothes conducted the interrogations. Interrogators almost always spoke Amharic, Ethiopia’s official language, and in many locations Oromia regional police acted as interpreters from Amharic to Afan Oromo.[82] Many former detainees described interrogators speaking Tigrinya or an “unknown language” to each other.[83]In some locations, detainees that Human Rights Watch interviewed who were as young as 15 said they did not understand the interrogators’ questions because they did not speak fluent Amharic and there was no interpretation.

Interrogators often accused protesters, particularly in the early months of the protests, of taking direction from outside agents, and regularly mentioned both the OFC and OLF. Many former detainees said they were questioned about family connections to opposition politics. Some said they were told they would be released if they identified those mobilizing students.[84] Detainees were also accused of providing information to diaspora or international media, particularly in November and December, and several people said their phones, Facebook accounts, and email accounts were searched during their detention. Many former detainees said they were interrogated the first night, and sometimes over the course of several nights.

Many students interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were released after several weeks, although some were detained for several months. Thousands remain in detention. Most of the individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch who were detained for more than one month described treatment that appeared to amount to torture. Tolessa, a first-year university student from Adama University, said:

We were recovering from the teargas and trying to find out who had been shot during the protest. Then the security forces stormed the dormitories. They blindfolded 17 of us from my floor and drove us two hours into the countryside. We were put into an unfinished building for nine days. Each night they would take us out one by one, beat us with sticks and whips, and ask us about who was behind the protests and whether we were members of the OLF. I told them I don’t even know who the OLF are but treating students this way will drive people toward the OLF. They beat me very badly for that. We would hear screams all night long. When I went to the bathroom, I saw students being hung by their wrists from the ceiling and being whipped. There were more than one hundred students [that] I saw. The interrogators were not from our area. We had to speak Amharic [the national language]. If we spoke Oromo they would get angry and beat us more.[85]

Badasa, 18, a Grade 9 student who was arrested before the protests in Adaba, in West Arsi zone, said that each night for three nights he was chained by the hands and wrists, had a metal pole positioned under his legs and was hung upside down between two desks. Badasa said the security officials beat the bottom of his feet and kept asking, “Who is behind you?” He told Human Rights Watch, “There were three spaces in the ‘torture room’ for others to be hung upside down that way. On the third night there were two others being questioned, they were screaming very loudly. The rest of the time it was just me.”[86]

Jamal, 19, a Grade 8 student from Chiro in West Hararghe, said he and three others were taken to a graveyard where they were beaten with a whip:

“You are terrorists, you are trying to mislead students and create insecurity,” the soldiers said to us. Another man was hung upside down by his ankles from a chain hanging from a tree and beaten with a stick. Blood was dripping from his head and he was unconscious. The rest of us were then taken back to the police station. We don’t know what happened to that other boy. We never saw him again.[87]

Negasu, a 24-year-old living in the outskirts of Addis Ababa, was arrested on February 19, 2016, the day after a protest. He said he was taken to military camp and beaten and questioned. At night he and four others were taken blindfolded to an unknown location, about a one-hour drive away. Wearing just their underwear, they were all hung upside down by their ankles in a small room and questioned about who was behind the protests. Following the interrogation, the room was closed and the officers burned rubber, filling the room with toxic smoke. Negasu fainted, and woke up when a federal police official poured cold water on him. He had previously been arrested during the 2014 protests and badly tortured in a different military camp.[88]

An unknown number of individuals have died of mistreatment while in detention. Human Rights Watch received credible reports of deaths in detention facilities in Bedeno woreda in East Hararghe, Kachisi in West Shewa zone, and in Nekemte town in East Wollega zone.

Several women said they were raped or sexually assaulted while in detention, almost exclusively in military camps. One woman said she was raped during an interrogation, but most said it occurred while they were being held in solitary confinement. Two cases documented by Human Rights Watch involved multiple soldiers.

A 22-year-old woman named Mona told Human Rights Watch that she was arrested the night of a protest in late December and taken to what she described as a military camp in the Borana zone. She was held in solitary confinement in total darkness. She said she was raped three times in her cell by unidentified men during her two-week detention. She believed there were two men involved each time. She was frequently pulled out of her cell and interrogated about her involvement in the protests and the whereabouts of her two brothers, who the interrogators suggested were mobilizing students. She was released on the condition that she would bring her two brothers to security officials for questioning.[89]

Meti, a woman in her 20s, was arrested in late December for selling traditional Oromo clothes the day after a protest in East Wollega:

I was arrested and spent one week at the police station. Each night they pulled me out and beat me with a dry stick and rubber whip. Then I was taken to [location withheld]. I was kept in solitary confinement. On three separate occasions I was forced to take off my clothes and parade in front of the officers while I was questioned about my link with the OLF. They threatened to kill me unless I confessed to being involved with organizing the protests. I was asked why I was selling Oromo clothes and jewelry. They told me my business symbolizes pride in being Oromo and that is why people are coming out [to protest]. At first I was by myself in a dark cell, but then I was with all the other girls that had been arrested during the protest.[90]

Most of the detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported crowded conditions, inadequate food and water, and often no food at all, particularly when individuals were detained for short periods. Families were not permitted to visit in most locations, and sometimes families who brought food to detainees were turned away – as happened in Jilanko and Ambo.[91] Men and women were kept in different cells in most locations. Children were detained with unrelated adults. Fifteen detainees described being kept in solitary confinement, 12 of them in military camps.[92]

All of these descriptions match established patterns of torture and ill-treatment of detainees that Human Rights Watch and other human rights groups have documented in Oromia’s many official and unofficial detention facilities.[93]

Denial of Medical Treatment, Harassment of Health Workers

Human Rights Watch documented multiple cases of Ethiopian security forces entering medical facilities in order to deny care to or apprehend injured protesters, and harassing or arresting healthcare workers for treating them. Such interference with the provision of medical care violates the right to health.

Human Rights Watch documented six cases of individuals who were unable to access medical treatment for injuries sustained during the protests because health workers were intimidated by security forces. Demiksa, a student from East Wollega, was refused medical treatment in late December 2015 for his injured arm and face after he was pushed to the ground in a panic when Oromia regional police fired teargas at protesters: “[The health workers] said they couldn’t treat me. Security forces had arrested two of their colleagues the day before because they were treating protesters. They were accused of providing health care to the opposition.”[94]

Garoma, a clinical nurse in a health clinic close to Ambo, also described soldiers coming to his clinic to find wounded protesters. He said:

There were three students injured, one from a bullet, and two with broken limbs from being hit by police at the protests. Soldiers came into the emergency room and asked, “Who are they? Why are you treating them?” They wanted to know what medicine I was giving them. Then they started questioning the students: “Were you in the demonstration? Is that how you got injured?” They took two of them away. The next night I had the day off but the same soldiers came back asking for me, demanding to know where I was. I decided to leave that town.

Garoma, a member of OFC, had previously been detained and tortured in a military camp for six months during the 2014 protests, and promised he would not involve himself in any future protests.[95]

Several health workers reported being targeted by security officials in the days following protests, usually by federal police or the military. They said that security forces harassed them and arrested some of their colleagues because they posted photos on social media showing their arms crossed in what has become a symbol of the protest movement. A health worker in East Wollega said he had been forced at gunpoint to treat a police officer’s minor injuries while student protesters with bullet wounds were left unattended. The health worker said at least one of those students died from his injuries that evening.[96]

Health workers in Nekemte town in East Wollega zone and in West Arsi zone told Human Rights Watch they were arrested following protests. In each case they were accused of treating injured students and of encouraging students to protest further. Five said that colleagues went missing in the days after the protests and were feared “disappeared.” In each case, those health workers had been threatened by security officials because of their perceived involvement in the 2014 protests, or by local OPDO cadres because they had refused to join OPDO. The disappearance of these health workers meant less qualified staff were available to treat the injured and other patients because limits on qualified staff in many small rural Oromia health facilities.

Denial of Access to Education

Students reported closures of schools in a variety of locations throughout all 17 zones in Oromia. Schools were often closed for several weeks around the time of the protests and many schools are still not fully functional because students are afraid to go to class, teachers have been arrested or forcibly disappeared, or parents have pulled their children out of school to avoid arrest. Local governments closed schools to prevent students from mobilizing, according to many students. Some students told Human Rights Watch that the lack of education left them no choice but to go back to their family farms or consider fleeing Ethiopia.

The government’s response to largely non-violent protests by shutting down schools is an unnecessary and disproportionate restriction of the right to education. The closures and other measures, such as the intimidating presence of security officials in classrooms, affected a large number of students, not just those who participated in protests. Closing schools, threatening teachers and effectively discouraging student attendance compounded the abuses involved in the government’s quashing of the right to expression and assembly in non-violent protests.

The government often uses suspension to punish students perceived to be involved in protests or expressing dissent against the government.[97]Security officials told students that they would not be allowed to return to their university because of their involvement in the protests, according to several students interviewed by Human Rights Watch. Several students in Grades 6, 8, 10, and 11 told Human Rights Watch that they had been released from detention on the condition they would not go back to school. The Grade 6 student said she had the highest marks in her class the previous year and was told by the principal she would not be allowed to go back to school because she attended the protests.[98] As a result, she decided to flee the country.

Teachers and administrators said they were arrested because their students protested. They also described the pressure they were under to monitor activities of students and to actively prevent protests. Security forces, usually military, occupied schools in some locations to deter protests. In some locations they were stationed outside of the compound, while in others they were inside the school, including in the classroom. In three locations where classes did resume, students and teachers described plainclothes security officers sitting in on classes. One teacher described being threatened when he resumed teaching in Arsi zone:

During the protest I was arrested and accused of inciting students. I was released on the condition I would talk them out of protesting. If there were any more protests, I would be killed. I signed a form that said this. Then there were plainclothes officers in my classroom pretending to be students, they don’t even speak Afan Oromo [the language of instruction] but their presence stops everyone from saying anything. Each day students stop coming or just disappear. Prior to the protests I had around 60 students, now I have just 17. All the best students were arrested, and many are just too afraid to show up.[99]

National examinations were scheduled for late May 2016. Oromo students petitioned local and federal government to have exams postponed because the ongoing disruption to education would disadvantage Oromo students writing these exams. On May 29, Oromo diaspora activists leaked the exams on social media. The federal government shortly thereafter postponed the national examinations.[100]

Conditions of Release and Restrictions on Movement