In 2025, Peru continued to backslide on democracy and human rights as Congress adopted measures that fostered impunity, weakened democratic institutions, and eroded judicial independence. Congress passed a broad amnesty law that grants impunity for serious crimes committed during the armed conflict.

Organized crime continued to expand across the country, leading to an increase in homicides, extortion, and other violent crimes.

On October 10, Congress ousted then-President Dina Boluarte, citing an obscure constitutional provision allowing it to declare that the presidency has been “vacated” if the president faces “moral incapacity.” José Jerí, the head of Congress, took office as interim president.

Threats to Judicial and Prosecutorial Independence

More than half of the lawmakers in Congress are facing investigations for corruption or other crimes. In recent years, Congress has taken steps to undermine the independence and capacity of courts and prosecutors.

In January 2025, authorities swore in a new seven-member National Board of Justice that, when it functions properly, plays a key role in safeguarding the separation of powers. An international mission of experts monitoring the selection process concluded that it “fail[ed] to meet international standards of transparency, publicity, technical criteria, and citizen participation.”

In September, the National Board of Justice appointed Tomás Gálvez as attorney general. Gálvez, who had been investigated for an influence peddling scheme known as “Cuellos Blancos,” said he would remove leading anti-corruption prosecutors. He had not removed them at time of writing.

Impunity for Human Rights Violations

In July, Congress passed an amnesty bill that grants impunity for serious crimes committed during the country’s internal armed conflict. President Boluarte enacted the law in August, despite an Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruling ordering Peru to halt implementation of the bill pending an analysis of its compatibility with the court’s prior rulings on amnesty laws.

Authorities have failed to adequately investigate the killing of 49 protesters and bystanders during large protests that took place between December 2022 and February 2023. As of September, nobody had been convicted for these killings. In July, prosecutors said that 70 percent of their investigations into the abuses remained in the “preparatory phase.”

In September, Congress shelved a constitutional complaint against President Boluarte regarding her role in the repression of the protests. The Public Prosecutor’s Office had charged Boluarte and several former ministers for failing to prevent homicides and injuries. Lawmakers argued that there was no evidence that Boluarte had ordered the abuses or knew about them when they happened.

Public Sector Corruption

Corruption remained a major driver of institutional decline in Peru. In 2024, Peru experienced a steep drop in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.

Five former presidents have been charged with corruption; four of them remained behind bars at time of writing.

In August, the Constitutional Court ordered the suspension of criminal investigations against President Boluarte until she finishes her term. At the time, the Attorney General’s Office was investigating her for allegedly receiving expensive watches from a provincial governor and for her alleged responsibility in the killings and injuries of protesters, among other alleged offenses. Prosecutors reactivated the investigations in October, after she was ousted and lost her immunity.

In January, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Working Group on Bribery sent a high-level mission to Peru. The group expressed concern over “developments that could jeopardize judicial and prosecutorial independence in Peru” including disciplinary investigations against prosecutors in charge of major corruption cases.

Security Policies

Crime remained a major concern for Peruvians. As of August, authorities had registered 1,377 homicides in 2025, a 14.6 percent increase compared to the same period in 2024. During the same period, criminal complaints alleging extortion rose by nearly 30 percent.

The year saw several protests in different parts of the country demanding government action to ensure security.

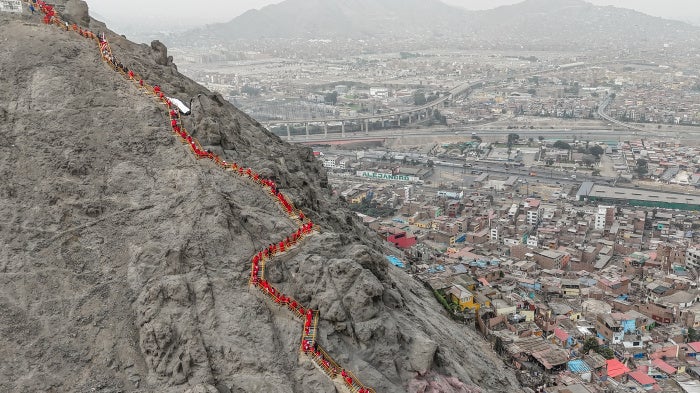

In September and October, protesters took to the streets across Peru demanding action against rising crime and political corruption. Many also protested Congress’s decision to appoint José Jerí as president. Clashes between police and protesters left one person dead and more than 70 people injured.

President Boluarte declared and extended states of emergency, suspending basic rights in parts of the country, including neighborhoods in Lima, the capital, and Callao, to respond to crime. As of June, these measures had failed to reduce homicides.

In April, Congress modified Peru’s law on asset forfeiture, making it harder for prosecutors to seize assets from defendants. Asset forfeiture laws often raise serious human rights concerns. However, a group of judges, prosecutors, and other officials said in a joint statement that the change in Peru weakened an essential legal tool to fight organized crime groups. President Boluarte signed the bill into law in May.

Shrinking Civic Space

Congress and the Boluarte administration created a hostile environment for human rights groups and independent journalists.

In March, Congress approved a law granting the Peruvian Agency for International Cooperation, a government agency, sweeping authority over media and civil society organizations that receive foreign funding. The law requires prior approval for activities conducted with foreign funding and bans the use of foreign funds to pursue legal action against the state, including in national and international human rights cases. In April, United Nations experts expressed concern about the impact of the international cooperation law on nongovernmental organizations and said the law was a “worrying curb on civic space and human rights work.”

In a speech in February, President Boluarte accused human rights groups of “undermin[ing] the authority of the state and delegitimiz[ing] the principle of order.”

Peruvian journalists reporting on matters of public interest often face abusive criminal defamation charges. At time of writing, Congress was discussing a bill that would expand defamation penalties to up to six years in prison.

In September 2025, Reporters Without Borders reported that eight investigative journalists were subjected to surveillance, judicial proceedings, and interception requests by police, senior officials, and political figures in retaliation for work that sought to expose alleged corruption involving President Boluarte, her brother Nicanor Boluarte, and Justice Minister Juan José Santiváñez.

At time of writing, Gustavo Gorriti, a leading investigative journalist, remained under criminal investigation for allegedly receiving sensitive information from prosecutors.

In September, the National Association of Journalists of Peru recorded more than 18 incidents of violence against journalists during protests, in most cases by police officers.

Journalists have also suffered deadly attacks. In January, unidentified assailants shot and killed journalist Gastón Medina dead outside his home in Ica, after he reported on alleged misuse of public funds and other irregularities in the regional government, provincial municipality, and local judiciary, and on extortion mafias targeting transport workers. In May, unknown assailants killed journalist Raúl Célis López in Iquitos. He had reported on alleged cases of corruption in the regional government, as well as on extortion and organized crime in the Amazon region.

Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

Data released in 2025 showed that nearly 28 percent of the population had incomes below the national monetary poverty line in 2024, a 1.4 percentage point decrease from 2023 but still significantly above the 20 percent figure from 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic. Poverty remained particularly high in rural areas (39.3 percent).

Extreme poverty—defined by the government as the inability to afford a basic food basket—increased to 5.5 percent of the population (approximately 1.9 million people), twice the 2019 level.

According to the International Labour Organization, by the end of 2024, 72 percent of workers were engaged in the informal economy, the highest rate in the region. In September, the OECD urged the government to address this situation and expand access to quality early childhood education, particularly for families with low incomes and rural communities.

That same month, young people from the “Generation Z” movement organized a protest in response to the Pension System Modernization Law, which Congress approved in 2024, and implemented by executive decree in September 2025. The law required all workers, including the self-employed, to enroll in either the public or private pension system and limited withdrawal options for younger contributors.

Environment and Human Rights

Mining has historically been one of Peru’s most important economic sectors. Peru’s mining industry, which extracts copper, gold, zinc, lead, and iron, among other minerals, represented 66 percent of Peru’s total exports in 2024.

The Peruvian Institute of Economics, a national economic research center, has estimated that illegal mining, most of it resulting from small-scale mining operations, accounted for roughly half—more than US$6.8 billion—of the country’s gold export value in 2024. Artisanal and small-scale mining can be an important source of income for many individuals with low incomes, but has a significant impact on the environment and public health in Peru.

In 2025, Congress continued to extend the deadline to incorporate illegal and informal miners into the legal mining economy. This has effectively allowed illegal miners to operate without accountability.

Groups involved in illegal exploitation of natural resources and the illegal occupation and appropriation of land have repeatedly threatened and attacked forest defenders.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Peru does not allow same-sex marriage or legal gender recognition for transgender people and lacks comprehensive anti-LGBT discrimination legislation.

In May, Peru enacted a law that purports to combat sexual violence against children and adolescents, but includes provisions that restrict use of public restrooms based on “biological sex,” which could exclude trans people from restrooms aligned with their gender identity. Vague language in the law could allow censorship of educational, artistic, or identity-based expression.

Reproductive Justice

Women, girls, and pregnant people can legally access abortions only when a pregnancy threatens their life or health; even then, they many face barriers.

In June, the National Maternal Perinatal Institute of Peru revised its therapeutic abortion guidelines in ways that effectively make it harder for women and girls to access abortion when their life or health is at risk.

Violence against Women and Girls

As of August, authorities had registered 105 femicides—defined as the killing of a woman or girl in certain contexts, including domestic violence.

The Ombudsperson’s Office noted an increase in cases of missing women, girls, and adolescents during the first half of the year, with more than 6,000 women reported missing.

In June, members of Congress introduced a bill that would impose prison sentences of up to six years for filing “false complaints” in domestic violence cases. Women’s rights groups warned that the bill would discourage victims from seeking help.

Foreign Policy and Human Rights Commitments

In August, President Boluarte announced the creation of a working group to analyze, among other things, whether and how Peru should withdraw from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which has played a key role in protecting the rights of Peruvians.