Ethiopia made little progress in 2017 on much-needed human rights reforms. Instead, it used a prolonged state of emergency, security force abuses, and repressive laws to continue suppressing basic rights and freedoms.

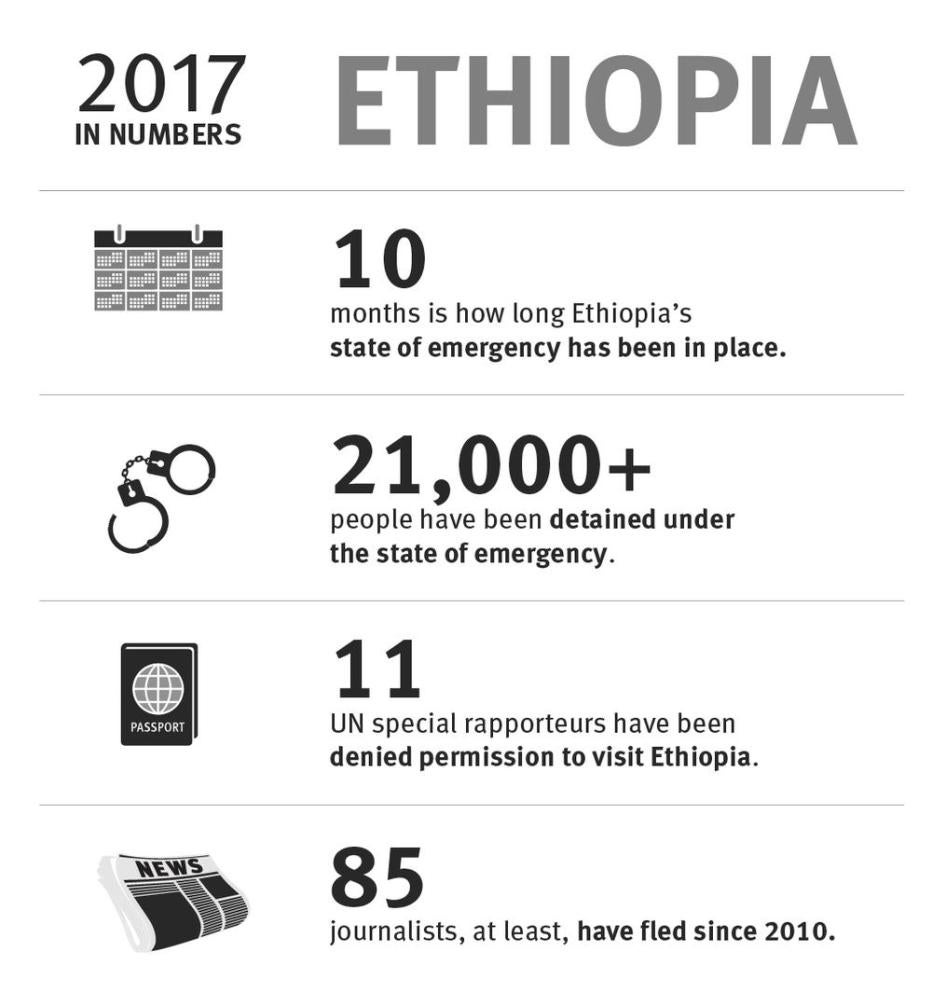

The 10-month state of emergency, first declared in October 2016, brought mass arrests, mistreatment in detention, and unreasonable limitations on freedom of assembly, expression, and association. While abusive and overly broad, the state of emergency gave the government a period of relative calm that it could have used to address grievances raised repeatedly by protesters.

However, the government did not address the human rights concerns that protesters raised, including the closing of political space, brutality of security forces, and forced displacement. Instead, authorities in late 2016 and 2017 announced anti- corruption reforms, cabinet reshuffles, a dialogue with what was left of opposition political parties, youth job creation, and commitments to entrench “good governance.”

Ethiopia continues to have a closed political space. The ruling coalition has 100 percent of federal and regional parliamentary seats. Broad restrictions on civil society and independent media, decimation of independent political parties, harassment and arbitrary detention of those who do not actively support the government, severely limited space for dissenting voices.

Despite repeated promises to investigate abuses, the government has not credibly done so, underscoring the need for international investigations. The government-affiliated Human Rights Commission is not sufficiently independent and its investigations consistently lack credibility.

State of Emergency

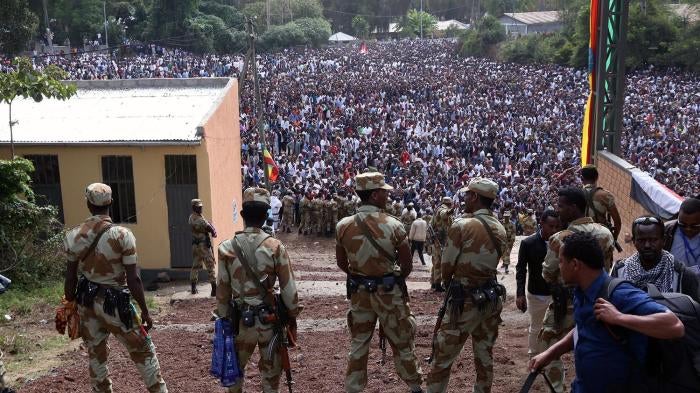

Ethiopia spent much of 2017 under a state of emergency first imposed in October 2016 following a year of popular protests, renewed for four months in March, and lifted on August 4. Security forces responded to the protests with lethal force, killing over 1,ooo protesters and detaining tens of thousands more.

The state of emergency’s implementing directive prescribed draconian and overly broad restrictions on freedom of expression, association, and assembly across the country, and signaled an increasingly militarized response to the situation. The directive banned all protests without government permission and permitted arrest without court order in “a place assigned by the command post until the end of the state of emergency” and permitted “rehabilitation”—a euphemism for short-term detention that often involves forced physical exercise.

During the state of emergency military were deployed in much larger numbers across Oromia and Amhara regions, and security forces arbitrarily detained over 21,000 people in these “rehabilitation camps” according to government figures. Detainees reported harsh physical punishment and indoctrination in government policies. Places of detention included prisons, military camps, and other makeshift facilities. Some reported torture. Artists, politicians, and journalists were tried on politically motivated charges.

Dr. Merera Gudina, the chair of the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), a legally registered political opposition party, was charged with “outrages against the constitution” in March. He joins many other major OFC members on trial on politically motivated charges, including deputy chairman Bekele Gerba. At time of writing, at least 8,000 people arrested during the state of emergency remain in detention, according to government figures.

Freedom of Expression and Association

The state tightly controls the media landscape, a reality exacerbated during the state of emergency, making it challenging for Ethiopians to access information that is independent of government perspectives. Many journalists are forced to choose between self-censorship, harassment and arrest, or exile. At least 85 journalists have fled into exile since 2010, including at least six in 2017.

Scores of journalists, including Eskinder Nega and Woubshet Taye, remain jailed under Ethiopia’s anti- terrorism law.

In addition to threats against journalists, tactics used to restrict independent media include harassing advertisers, printing presses, and distributors.

Absent a vibrant independent domestic media, social media and diaspora television stations continue to play key roles in disseminating information. The government increased its efforts to restrict access to social media and diaspora media in 2017, banning the watching of diaspora television under the state of emergency, jamming radio and television broadcasts, targeting sources and family members of diaspora journalists. In April, two of the main diaspora television stations—Ethiopian Satellite Television (ESAT) and the Oromia Media Network (OMN)—were charged under the repressive anti-terrorism law. Executive director of OMN, Jawar Mohammed, was also charged under the criminal code in April.

The government regularly restricts access to social media apps and some websites with content that challenges the government’s narrative on key issues. During particularly sensitive times, such as during June’s national exams when the government feared an exam leak, the government blocked access to the internet completely.

The 2009 Charities and Societies Proclamation (CSO law) continues to severely curtail the ability of independent nongovernmental organizations. The law bars work on human rights, governance, conflict resolution and advocacy on the rights of women, children, and people with disabilities by organizations that receive more than 10 percent of their funds from foreign sources.

Torture and Arbitrary Detention

Arbitrary detention and torture continue to be major problems in Ethiopia. Ethiopian security personnel, including plainclothes security and intelligence officials, federal police, special police, and military, frequently tortured and otherwise ill-treated political detainees held in official and secret detention centers, to coerce confessions or the provision of information.

Many of those arrested since the 2015/2016 protests or during the 2017 state of emergency said they were tortured in detention, including in military camps. Several women alleged that security forces raped or sexually assaulted them while they were in detention. There is little indication that security personnel are being investigated or punished for any serious abuses. Former security personnel, including military, have described using torture as a technique to extract information.

There are serious due process concerns and concerns about the independence of the judiciary on politically sensitive cases. Outside Addis Ababa, many detainees are not charged and are rarely taken to court.

Individuals peacefully expressing dissent are often charged under the repressive anti-terrorism law and accused of belonging to one of three domestic groups that the government has designated as terrorist organizations. The charges carry punishments up to life in prison. Acquittals are rare, and courts frequently ignore complaints of torture by detainees. Hundreds of individuals, including opposition politicians, protesters, journalists and artists, are presently on trial under the anti-terrorism law.

The government has not permitted the United Nation’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to investigate allegations despite requests from the UN body in 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, and 2015.

Somali Region Security Force Abuses

Serious abuses continue to be committed by the Somali Region’s notoriously abusive Liyu police. Throughout 2017, communities in the neighboring Oromia regional state reported frequent armed attacks on their homes by individuals believed to be from the Somali Region’s Liyu police. Residents reported killings, assaults, looting of property, and displacement. Several Somali communities reported reprisal attacks carried out by unknown Oromo individuals. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any efforts by the federal government to stop these incursions. Several hundred thousand people have been internally displaced as a result of the ongoing conflict.

The Liyu police were formed in 2008 and have a murky legal mandate but in practice report to Abdi Mahmoud Omar (also known as “Abdi Illey”) the president of the Somali Regional State, and have been implicated in numerous alleged extrajudicial killings as well as incidents of torture, rape, and attacks on civilians accused of proving support to the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF). No meaningful investigations have been undertaken into any of these alleged abuses in the Somali Regional State.

Abdi Illey’s intolerance for dissent extends beyond Ethiopia, and family members of Ethiopian Somalis living outside of the country are frequently targeted in the Somali Region. Family members of diaspora have been arbitrarily detained, harassed, and had their property confiscated after their relatives in the diaspora attended protests or were critical of Abdi Illey in social media posts.

Key International Actors

Despite its deteriorating human rights record, Ethiopia continues to enjoy strong support from foreign donors and most of its regional neighbors, due to its role as host of the African Union and as a strategic regional player, its contributions to UN peacekeeping, regional counterterrorism efforts, its migration partnerships with Western countries, and its stated progress on development indicators. Ethiopia is also a country of origin, transit, and host for large numbers of migrants and refugees.

Both the European Parliament and US Senate and House of Representatives have denounced Ethiopia’s human rights record. The European Parliament urged the establishment of a UN-led mechanism to investigate the killings of protesters since 2015 and to release all political prisoners. In April, European Union Special Representative (EUSR) for Human Rights Stavros Lambrinidis visited Ethiopia, underscoring EU concern over Ethiopia’s human rights situation. Other donors, including the World Bank, have continued business as usual without publicly raising concerns.

Ethiopia is a member of both the UN Security Council and the UN Human Rights Council. Despite these roles, Ethiopia has a history of non-cooperation with UN special mechanisms. Other than the UN special rapporteur on Eritrea, no special rapporteur has been permitted to visit since 2006. The rapporteurs on torture, freedom of opinion and expression, and peaceful assembly, among others, all have outstanding requests to visit the country.