Prime Minister Hun Sen’s government launched new assaults on human rights in Cambodia, especially during the second half of 2015, arresting and jailing members of the political opposition and activists, and passing a draconian new law on nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that the government rushed through the National Assembly on July 13. Other repressive laws were also proclaimed or proposed, including laws or regulations on the Internet, as Hun Sen, who has ruled since 1985, increasingly undermined fundamental human rights.

Opposition leader Sam Rainsy attempted to establish a “culture of dialogue” with Hun Sen and the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP), but his initiative failed to stem arrests or attacks on the opposition, and on November 13, 2015, a politically motivated arrest warrant was issued for him based on a conviction for peaceful expression in 2011.

Land confiscations also continued in 2015, and corruption remained rampant. Cambodia is a party to the United Nations Refugee Convention, but authorities refused to register more than 300 Vietnamese Montagnard asylum seekers for determination of their claims and summarily deported at least 54 of them to Vietnam.

Politically Motivated Prosecution and Assault

On July 13, a Phnom Penh court launched an investigation to consider bringing defamation and interference with justice charges against prominent NGO figure Ny Chakriya, who had raised questions about the independence of the judiciary in a land-grabbing case.

On July 21, 11 opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) organizers, on trial since 2014 on trumped-up charges of leading or participating in an anti-government “insurrection,” were suddenly convicted and sentenced by a Phnom Penh court to 7 to 20 years in prison. Despite the absence of evidence connecting them to any criminal acts, they were found responsible for crowd violence that erupted when government security forces broke up a peaceful CNRP-led demonstration calling for the reopening of Phnom Penh’s “Freedom Park” on July 15, 2014. The convictions were accompanied by official warnings that seven CNRP National Assembly members also charged with insurrection in connection with the same incident could be convicted and imprisoned despite their parliamentary immunity. Following this, Hun Sen convened a closed meeting of almost 5,000 of the top CPP security force officials at which he issued an “absolute order” that security forces must “ensure there would be no color revolution” in Cambodia by “eliminating acts by any group or party” deemed “illegal.”

On August 4-5, following Hun Sen’s public call for more arrests of those allegedly responsible for the July 2014 Freedom Park violence, police detained three CNRP activists who were then charged with participating in the purported insurrection, while arrest warrants were issued for several others.

On August 13, Hun Sen ordered the arrest of Hong Sok Hour, an opposition party senator who the previous day had posted a video clip on Facebook including footage of the Cambodia-Vietnam border and of a badly translated excerpt from the 1979 Cambodia-Vietnam friendship agreement. Disregarding the senator’s parliamentary immunity, a “counter-terrorism” security force contingent under the authority of Hun Sen’s son-in-law detained him. More arrests followed between late August and early October 2015, including of a student who posted a Facebook message advocating a “color revolution.”

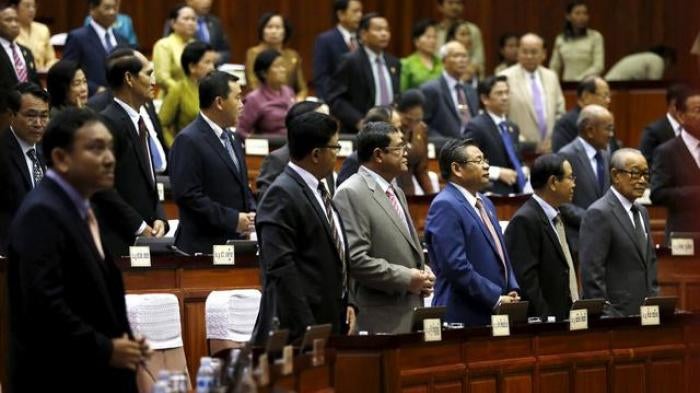

On October 26-27, following public encouragement by Hun Sen to conduct anti-CNRP demonstrations, elements of the prime minister’s bodyguard unit and others in civilian clothes brutally assaulted two CNRP parliamentarians outside the National Assembly. Three persons were arrested and charged with the attack, but others involved who were photographed were not taken into custody. The CNRP thereafter stopped attending National Assembly sessions, citing security concerns.

On November 13, following repeated warnings by Hun Sen that Sam Rainsy was liable to criminal prosecution, the Phnom Penh court issued an arrest order to belatedly enforce a judicial ruling of March 2013 confirming a two-year sentence related to Rainsy’s allegation that Cambodian Foreign Minister Hor Namhong was implicated in crimes committed when the Khmer Rouge ruled Cambodia. The French Supreme Court, citing international human rights standards, had previously ruled that these comments were a legitimate exercise of freedom of expression. On November 19 and December 1, the Phnom Penh Court targeted him with additional new trumped-up criminal actions.

Legislation Restricting Civil Society

The new NGO law allows the authorities to arbitrarily deny NGOs registration and shut them down. The law is aimed at critical voices in civil society and could seriously undermine the ability of many domestic and international associations and NGOs, as well as community-based advocacy movements, to work effectively in Cambodia.

Its restrictions on the right to freedom of association go well beyond the permissible limitations allowed by international human rights law. The law gives the interior, foreign affairs, and other ministries sweeping, arbitrary powers to shut down domestic and foreign membership groups and organizations, unchecked by judicial review, and allows them to prohibit the creation of new NGOs. It requires registered groups to operate under a vaguely defined obligation of “political neutrality,” on pain of dissolution, and criminalizes activities by unregistered groups.

After passage of the law, Hun Sen and other government officials launched a campaign against human rights-oriented NGOs, including those focusing on land disputes and women’s rights. The authorities began to insist that grassroots civil society activities could no longer be carried out unless those involved had registered with the government in accordance with the new provisions, giving the government wide authority to decide what activities can and cannot take place.

On August 19, the government issued a sub-decree upgrading the status of an anti-cybercrime unit and empowering it to “investigate and take measures in accordance with the law with regard to actions via the internet of instigation, insult, racial discrimination, and generation of social movements,” particularly those that might lead to a “color revolution.”

On November 30, the government put a draft telecommunications law before the National Assembly, even though doing so was not inscribed in the legislature’s agenda. The draft had never been made available for discussion by concerned civil society organizations. The CPP adopted it without parliamentary debate. The law gives government authorities arbitrary powers to issue orders to telecommunications operators, to secretly monitor and record telecommunications, and to imprison people for using telecommunications in a manner deemed to endanger “national security.”

Arbitrary Detention, Torture, and Other Ill-Treatment

The authorities, especially in Phnom Penh, launched repeated street sweeps that detained hundreds of alleged drug users, homeless people, beggars, street children, sex workers, and people with disabilities in so-called drug treatment or social rehabilitation centers. Detainees never saw a lawyer or a court, nor had any opportunity to challenge the legality of their detention. Detained individuals received no meaningful training or health care, and faced torture, ill-treatment, and other abuses including, in some centers, forced labor. During 2015, at least three died in suspicious circumstances.

Khmer Rouge Tribunal

Numerous public statements by Cambodian officials and the start in June of publication of previously confidential court materials revealed numerous instances of government non-cooperation with the United Nations-assisted Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), set up to prosecute those most responsible for crimes committed by the Khmer Rouge from 1975-79.

While the government allowed a trial of two former leaders of the Khmer Rouge government, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, on charges of crimes against humanity, genocide, and war crimes, it refused to carry out orders by a UN secretary-general-nominated investigating judge to arrest two other former Khmer Rouge leaders, Meas Muth and Im Chem.

This violated the 2003 UN-Cambodia agreement establishing the ECCC and continued a long pattern of opposition by Hun Sen to additional prosecutions. The government’s non-cooperation has seriously undermined possibilities for investigating suspects whom Hun Sen, himself a former Khmer Rouge commander, does not want brought to justice.

Asylum Seekers and Refugees

Since late 2014, a wave of Montagnard ethnic minority asylum seekers from Vietnam has arrived in Cambodia. Most of them practice forms of Christianity that Vietnamese authorities characterize as “evil way” religion. In early 2015, Cambodia recognized 13 as refugees but refused to allow more than 300 other Montagnards to register as asylum seekers. At least 54 were summarily returned to Vietnam in violation of the Refugee Convention, while those remaining in Cambodia faced the threat of similar deportation, and some decided their best option was to return “voluntarily” to Vietnam.

In June 2015, the government implemented a deal with Australia to resettle some of the refugees held on the island of Nauru, but conditions for refugees in Cambodia were so inadequate that only four refugees agreed to relocate. In September, one of the four decided to leave Cambodia.

Key International Actors

China, Vietnam, Japan, and South Korea were Cambodia’s leading foreign investors in 2015, while Japan, the European Union, and the United States were the leading foreign donors. Vietnam was by far Cambodia’s most important partner in security matters, followed by China. The US provided limited military training, and was more outspoken than others about human rights violations in Cambodia. The EU only rarely commented on human rights in public, and almost all others were silent.

The World Bank, which suspended new lending to Cambodia in 2011 because the government had forcibly evicted people in a manner violating the bank’s policy, considered resuming funding for government land projects in 2015 but at time of writing had not done so. The bank said nothing publicly about government repression of land rights advocates.