Summary

“Please, bring me back to Canada. … Please, forgive me. Let me be who I am, a Canadian.”

—Kimberly Polman, Canadian detained in camp for ISIS family members in Northeast Syria

More than one year ago, in March 2019, local fighters aided by a US-led, international coalition routed the Islamic State (ISIS) from the Syrian town of Baghouz, the last holdout of the group’s self-declared caliphate. In addition to capturing Syrians, the US-backed fighters, called the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), rounded up thousands of others who had been living under ISIS—men, women, and children from more than 60 countries. Since then, these foreigners have been arbitrarily detained in filthy and often inhuman and life-threatening conditions by authorities in northeast Syria, with the tacit approval of the Global Coalition Against ISIS, whose members include Canada. The detainees include at least 47 Canadians.

Like the other foreigners, the Canadians—8 men, 13 women, and 26 children, most under age 6—have not been charged with any crime. Nor have northeast Syrian authorities brought them before a judge to review the legality and necessity of their detention. The innocent, such as the children who never chose to be born or live under ISIS, have no hope of leaving. Meanwhile, any detainees potentially implicated in ISIS crimes may never face justice.

In makeshift prisons for men and adolescent boys, food is scarce and overcrowding is so severe that many of the detainees must sleep shoulder to shoulder. More than 100 prisoners and possibly several hundred have died, many from lack of care, since mid-2019. In locked camps for women, girls, and younger boys, tents collapse in strong winds or flood with rain or sewage. Some women, including at least one Canadian, say they are on an ISIS “kill list” for not supporting the group. Drinking water is often contaminated or in short supply. Latrines are overflowing, wild dogs scavenge mounds of garbage littering the grounds, and illnesses including viral infections are rampant. Medical care is grossly inadequate. The Kurdish Red Crescent reported that at least 517 people, 371 of them children, died in 2019, many from preventable diseases, in al-Hol—the larger of two camps for women and children, with about 65,000 detainees.

For months and in some cases years, the detained Canadians have been begging to come home, with many of the adults among them saying they are ready to stand trial for any suspected ISIS crimes. At the same time, family members in Canada have been beseeching the Canadian government to help them bring home their relatives. Four relatives even traveled to northeast Syria in failed quests to help their detained loved ones. The Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration for Northeast Syria, which is detaining the foreigners, has repeatedly called on all countries to repatriate their nationals or provide them with funds to investigate and prosecute suspects locally.

Canadian officials met the Autonomous Administration in 2018 to discuss repatriations, but Canada has yet to bring home or facilitate the return of any of its citizens—not even children like Amira, a 5-year-old orphan who said her parents and three siblings were killed in Baghouz during a 2019 air strike.

This report finds that the government of Canada is flouting its international human rights obligations toward Canadians who are arbitrarily detained in northeast Syria and providing inadequate support to family members seeking to provide their loved ones with essentials such as food and medicine, and to bring them home. The obligations that Canada has breached include taking necessary and reasonable steps to assist nationals abroad facing serious abuses including risks to life, torture, and inhuman and degrading treatment.

The report also finds that the Canadian government may be unlawfully withholding or limiting effective consular assistance to its citizens detained in northeast Syria based on their suspected links to ISIS—a transnational, Islamist armed group that has committed countless atrocities including war crimes, crimes against humanity, and apparent genocide. International law forbids withholding consular services in a discriminatory or arbitrary manner because of factors such as a person’s religion or their political or other views.

Family members of detainees told Human Rights Watch that Canadian authorities have not even contacted their detained relatives, much less improved their conditions of detention. Nor has Canada facilitated verification of citizenship for the 20 or more children born in Syria to Canadian parents, leaving them without an officially recognized nationality. Family members said the government will not even tell them whether they will be charged with support for terrorism if they send money to their detained relatives for food, medicine, and warm clothes.

“Kiran,” a family member in Canada, burst into tears as she described her fear over not knowing if she would be punished if she sent aid to her three grandchildren:

Do they just want them to die? That’s what it seems like. … These children, where are they going to get food, medicine, vitamins? … You’re not helping them survive, and you’re not letting me help them.

Families’ fears have been compounded by the spread to Syria of the deadly Covid-19 virus, which thrives on overcrowding, poor sanitation, and the physically frail. Because of Covid-19, “Jack's life is more at risk than ever before,” Sally Lane, the mother of imprisoned Canadian Jack Letts, wrote in an email to Global Affairs Canada—the government’s foreign office—that she shared with Human Rights Watch. “Is the government of Canada going to allow our son to die in prison in NE Syria?”

At time of writing, Canada had repatriated or assisted the returns of more than 40,000 citizens and permanent residents from 100 countries in response to Covid-19, including 29 from Syria—but not one of at least 47 citizens held without charge in northeast Syria.

Canadian officials say security risks and the lack of a consular presence in Syria have precluded them from doing more for the detainees. “Given the security situation and the lack of a physical presence on the ground, the Government of Canada’s ability to provide consular assistance in any part of Syria is extremely limited,” Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister François-Philippe Champagne wrote in a letter to Human Rights Watch in June 2020. “Nevertheless, Canadian consular officials are engaged directly with the Canadians in the custody of the [Autonomous Administration] … or their family members in Canada, to monitor their location and well-being.” Champagne also said Global Affairs has established a communication channel with regional authorities in northeast Syria “to advocate for the [detainees’] well-being to the extent possible.”

Yet at least 20 countries have repatriated anywhere from one to hundreds of their citizens from the same camps and prisons in northeast Syria including, since mid-October 2019, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States. France repatriated 10 children as recently as June 2020.

Global Affairs has told family members that they will help detainees who reach their consulates abroad. But short of escaping locked camps and prisons, traversing a war zone, and crossing borders, all without funds or identification papers, these detained citizens have no way to reach Canadian consulates that are hundreds of kilometers away in neighboring Iraq or Turkey unless Canada acts.

This report is based on Human Rights Watch research including interviews between December 2019 and April 2020 with 11 family members of Canadians detained in northeast Syria. The family members were based in Canada or abroad and are related to 19 Canadians held in northeast Syria, from 10 different families. Human Rights Watch researchers also interviewed four Canadian detainees—one in northeast Syria in February 2019, two in northeast Syria in June 2019, and one by telephone in April 2020. In addition, Human Rights Watch spoke with Canadian government officials, members of the Autonomous Administration, humanitarian aid groups working in northeast Syria, and lawyers, civil society members, and others seeking to repatriate the detainees. We also reviewed communications from the detainees to family members and Canadian officials. Human Rights Watch researchers have interviewed dozens of detainees during visits to the northeast Syrian camps in 2018 and in February and June of 2019.

At time of writing, no local, regional, or international options for investigations and prosecutions of the foreigners were under active consideration by governments with citizens detained in northeast Syria. In 2019, Western governments discussed, but did not pursue the idea of establishing a criminal tribunal in the region to prosecute foreign ISIS suspects. In February 2020, an increasingly frustrated Autonomous Administration announced that it would prosecute foreign ISIS suspects itself, but two months later, said it had indefinitely suspended the plan.

In two binding resolutions on so-called “foreign terrorist fighters” since 2014, resolution 2178 of 2014 and 2396 of 2017, the United Nations Security Council called on member states—which include Canada—to ensure that any person who “participates in the financing, planning, preparation or perpetration of terrorist acts or in supporting terrorist acts is brought to justice.” Resolution 2396 also requires countries to “develop and implement comprehensive and tailored prosecution, rehabilitation, and reintegration strategies and protocols, in accordance with their obligations under international law, including with respect to foreign terrorist fighters and [their] spouses and children.”

Given the absence of options for credible accountability in northeast Syria, the only way to potentially hold to account any Canadians implicated in serious ISIS crimes is for Canada to bring them home for investigation and, if warranted, prosecution. Leaving ISIS suspects and family members in indefinite, arbitrary detention, with no means to legally challenge their deprivation of liberty, also constitutes a form of collective punishment—one for which Canada, through its failure to help its citizens, is partially responsible.

Rehabilitation is also impossible in northeast Syria given the lack of psychosocial and medical services in the camps and prisons holding the foreigners. Reintegration is impossible as well, given that the Canadians are detained in a desert nearly 9,000 kilometers from their homeland. This leaves repatriation as the only way that UN member states can fulfill the Security Council requirement to rehabilitate and reintegrate their nationals. Repatriation would also fulfil Canada’s duty to make all necessary and feasible efforts to protect its citizens from torture or other inhuman or degrading treatment, and risks to life, and to help children fulfil their right to a nationality.

For all these reasons, Canada should, as a matter of urgent priority, repatriate all Canadians detained in northeast Syria for rehabilitation, reintegration, and, if appropriate, prosecution. Repatriation measures that Canada should take include promptly verifying citizenship, issuing citizens travel documents, and providing or coordinating safe passage from northeast Syria to Canadian consulates or territory. In keeping with the rights of the child, which Canada has championed at multiple UN fora, the government should prioritize the repatriation of the Canadian children and recognize them first and foremost as victims of ISIS. Children who may have been affiliated with ISIS should be considered victims and only prosecuted in exceptional cases as a last resort. Children should not be repatriated without their mothers—who may themselves be victims of ISIS—absent compelling evidence that separation is in the best interest of the child.

In the meantime, Canada should ensure that all of its citizens held in northeast Syria have an effective means to request consular assistance such as obtaining passports or other identity cards, and to contest their arbitrary detention and inhuman and degrading conditions of confinement. It should also increase humanitarian assistance to address the dire conditions for its nationals detained in northeast Syria.

Human Rights Watch deplores armed extremist attacks and recognizes that Canada has a legal obligation to protect individuals on its territory. We also recognize that Canada faces security challenges in visiting its citizens in person or helping bring them home. But abandoning citizens, most of them young children, to indefinite, unlawful detention in deeply degrading conditions will not make Canada safer. Instead, it denies ISIS victims and their families their day in court, while creating grievances that risk aiding ISIS recruitment drives and perpetuating cycles of violence.

Recommendations

To the Government of Canada

Including Prime Minister’s Office, Global Affairs Canada, Public Safety Canada, the Department of Justice, and Parliament:

- Repatriate, as a matter of urgent priority, all Canadian citizens detained in northeast Syria, giving priority to children, persons requiring urgent medical assistance, and other particularly vulnerable detainees. Bring home mothers or other adult guardians with their children absent compelling evidence that separation is in the best interest of the child, in line with international legal obligations with respect to family unity. Repatriation measures that Canada should take include promptly verifying citizenship, issuing citizens travel documents, and providing or coordinating safe passage from northeast Syria to Canadian consulates or territory;

- Pending repatriations, work with humanitarian agencies and local authorities to help improve conditions in the northeast Syria camps and prisons, including overcrowding and lack of hygiene and medical care, and to create a system whereby families can send funds to detainees in northeast Syria to use exclusively for essential provisions such as food, medicine, and clothing;

- Upon detainees’ return, offer them rehabilitation and reintegration services and, as appropriate, investigate and prosecute those suspected of serious crimes in line with international fair trial standards;

- Ensure that the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Program, including the Sensitive and International Investigations Section of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, is adequately resourced and staffed, including for investigations of any Canadians suspected of involvement in serious international crimes committed abroad;

- Investigate all allegations of torture and inhuman treatment of Canadians detained in northeast Syria. Press for accountability for detaining authorities responsible for any confirmed ill-treatment;

- Enact into Canadian law a right to effective consular assistance;

- Establish an office to independently review consular services with the aim of advocating on behalf of citizens and ensuring full compliance with the international legal obligation to provide consular assistance without discrimination;

- Support adoption of a universal set of standards on consular support by countries for their foreigners detained abroad that emphasizes the obligation to provide adequate and effective assistance.

Global Affairs Canada:

- Pending repatriations, immediately provide effective and robust consular assistance to Canadian citizens arbitrarily detained in northeast Syria and take all feasible measures to ensure their humane treatment. As part of this effort, ensure all detained citizens have an effective means to communicate with consular officials, promptly respond to requests for consular assistance from the detainees as well as from their family members in Canada or elsewhere, clarify policies on verification of Canadian citizenship, and regularly provide Canadian families with timely information about their detained relatives;

- Enforce a zero-tolerance policy toward discriminatory provision of consular services.

Department of Justice, Public Prosecution Service of Canada, and Public Safety Canada, including the Royal Canadian Mounted Police:

- Prioritize, as appropriate, investigations and prosecutions of returned detainees who may be implicated in serious international crimes—namely, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and potential acts of genocide;

- In determining criminal justice responses for all suspects, including women and children, consider the different roles that they may have served in ISIS as well as their potential roles as victims, whether of ISIS—including as women and children who were trafficked or otherwise lured, groomed, or pressured by ISIS to join the group—or of detaining authorities in northeast Syria.

- Where convictions are secured, consider alternatives to incarceration for women caring for young children. In cases of incarceration, make all feasible efforts to locate the women in facilities where their children can regularly visit them;

- Treat children affiliated with ISIS first and foremost as victims, recognizing that any recruitment or use of children below the age of 18 by non-state armed groups is a violation of international law. Prosecute and detain children only as an exceptional measure of last resort, in line with the Convention on the Rights of the Child, its optional protocol on the involvement of children in armed conflict, and juvenile justice standards. Raise the age of criminal responsibility in Canada for all crimes from 12 years old to at least 14 to 16 years old, in line with United Nations recommendations;

- Regularly review any use of monitoring or preventive measures for returned ISIS suspects, such as “peace bonds” and travel bans, to ensure that they are not disproportionate;

- Provide returned detainees with rehabilitation and reintegration services including medical and psychosocial support. Tailor programs for gender, age, educational needs, cultural background, and each returnees’ circumstances, including their potential status as victims of ISIS.

To the Autonomous Administration of Northeast Syria, including the Syrian Democratic Council and the Syrian Democratic Forces

- Absent or pending repatriations, promptly bring detained foreign nationals before a credible court to determine the necessity and legality of their detention. Release all detainees who are not charged with a prosecutable offense or those whose detention has not been approved by a court;

- Immediately improve conditions such as overcrowded and unsanitary prison cells and camps, insufficient outdoor time for prisoners, and inadequate healthcare, in line with international standards including the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (“Mandela Rules”). Grant access to humanitarian actors to promptly provide life-saving assistance;

- Detain children only as an exceptional measure of last resort and ensure any detained children are held separately from adults;

- Publish a list of prisoners who died in detention and share information with families including name, nationality, cause of death, and where they are buried;

- Arrange for the safe release of the most vulnerable prisoners on humanitarian grounds, including the physically disabled and terminally ill;

- Ensure detainees are informed of their right to request consular assistance and have a means to communicate with consular officials;

- Facilitate communications between detainees and their family members based abroad as well as family members detained separately in northeast Syria for suspected ISIS links;

- Assist countries and families seeking to repatriate detained foreigners to their home countries where they are not at risk of torture, ill-treatment, or unfair trials. Investigate allegations of torture or ill-treatment of detainees and hold those responsible to account.

To United Nations Entities

Including the Secretary General, the Security Council, the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the UN Office of Counter-Terrorism (UNOCT), and the UN Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

- Press the Canadian government to repatriate its citizens, first and foremost the detained Canadian children.

- Increase efforts to coordinate a prompt and robust international response to the indefinite, arbitrary detentions of foreign ISIS suspects and family members, in line with international human rights standards, binding UN Security Council Resolution 2178 of 2014 and Resolution 2396 of 2017, as well as the Mandela Rules and the Madrid Guiding Principles of 2015 and Addendum of 2018 on responses to the foreign fighter phenomenon. This response should include:

- Immediate repatriations of all citizens to their home countries provided they do not face risk of torture or other inhuman treatment upon return, prioritizing the returns of children, persons requiring urgent medical assistance, and other particularly vulnerable individuals;

- Rehabilitation and reintegration programs for returnees;

- Prosecutions as appropriate in home countries that can provide fair trials;

- Third-country resettlement and, if appropriate, prosecutions for detainees facing risk of torture or other inhuman treatment, or unfair trials, if returned home;

- Immediate increases in humanitarian access and aid to northeast Syria camps and prisons with the goal of ending dire and often life-threatening conditions;

- Assistance to detaining authorities in northeast Syria to create a credible court to promptly and fairly review the legality and necessity of detentions.

To Donors and Members of the Global Coalition Against ISIS, including Canada

- Press for and provide support to home countries to bring home foreigners detained in northeast Syria in cases where returnees are not at risk of torture, ill-treatment, and unfair trials upon return, giving urgent priority to children, persons requiring urgent medical assistance, and other particularly vulnerable individuals;

- Press home countries to rehabilitate, reintegrate and, as appropriate, investigate and prosecute returnees from northeast Syria in line with international fair trial and juvenile justice standards;

- Assist in resettlement and, if appropriate and feasible, prosecutions in third countries for detainees facing risk of torture or other inhuman treatment, or unfair trials if returned home.

Pending repatriations and resettlements:

- Immediately increase humanitarian aid to the camps and prisons in northeast Syria with the goal of ending dire and often life-threatening conditions, and ensuring adequate health care including prevention, testing, and treatment for Covid-19, tuberculosis, scabies, and other diseases, as well as to shelter, clean water, sanitation, and, for children, education;

- Coordinate humanitarian assistance from foreign donors and the Global Coalition Against ISIS with relevant humanitarian actors in northeast Syria;

- Press the Autonomous Administration of northeast Syria and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to facilitate regular and effective communication between detainees and their family members—both relatives abroad and those detained separately in northeast Syria for suspected ISIS links—and provide technical and financial assistance for such communication;

- Promptly assist detaining authorities in northeast Syria in setting up a credible court to fairly and impartially review of the legality and necessity of detentions of foreigners in camps and prisons;

- Provide financial and technical support to the detaining authorities in northeast Syria to ensure all prisoners are held in official detention centers built to accommodate detainees and meet basic international standards, including juvenile justice standards.

Methodology

This report is based on Human Rights Watch research between February 2019 and May 2020 including interviews with Canadians held in northeast Syria and with Canadian detainees’ family members in Canada and elsewhere, as well as multiple trips to detention camps for ISIS suspects and relatives in northeast Syria. Between December 2019 and June 2020, two Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 11 Canadians in Canada or other countries who were related to 19 Canadians held in northeast Syria. The interviews were conducted in person in Canada or by telephone to Canada and elsewhere. Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed four Canadian detainees—three during trips to northeast Syria in February and June 2019 and a fourth by telephone in April 2020.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed dozens of women and children of different nationalities who were held as family members of ISIS suspects during visits to al-Hol and Ain Issa, two camps in northeast Syria, in February 2019, and in three return visits to al-Hol camp in June 2019. We also reviewed several communications between family members and Canadian consular officials, as well as text messages between detainees and family members, that were shared by relatives of the detainees.

Most family members or detainees requested that Human Rights Watch withhold identifying information such as their names and locations, fearing harassment from members of the public in Canada, or reprisals against their detained relatives by prison or camp authorities, or other detainees. All pseudonyms appear in quotation marks on first reference.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed members of Canada-based non-governmental organizations and Canadian lawyers seeking to bring home Canadians from northeast Syria. We spoke with Canadian journalists as well as members of humanitarian organizations working in al-Hol and Roj, the camps holding Canadians and other foreigners. In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed officials from Global Affairs Canada, Public Safety Canada, and the Canadian Prime Minister’s office in Ottawa, as well as the co-chair of the Foreign Relations Commission for the Autonomous Administration of Northeast Syria.

Interviews were conducted in English, French, or Arabic. All interviews were voluntary. Interviewees received no compensation beyond reimbursement for travel expenses to those who traveled to meet with us.

In January 2020 and again in February, Human Rights Watch submitted our preliminary findings and requests for comment to the Canadian Prime Minister’s Office, Global Affairs Canada, and Public Safety Canada. In June, Human Rights Watch received one reply, a letter from Foreign Affairs Minister François-Philippe Champagne that included partial responses.

In June, Human Rights Watch repeatedly wrote to the Syrian Democratic Council and the Syrian Democratic Forces, the Autonomous Administration’s highest political authority and its armed force, respectively, requesting comment on the conditions in prisons detaining foreign ISIS suspects. We did not receive a reply.

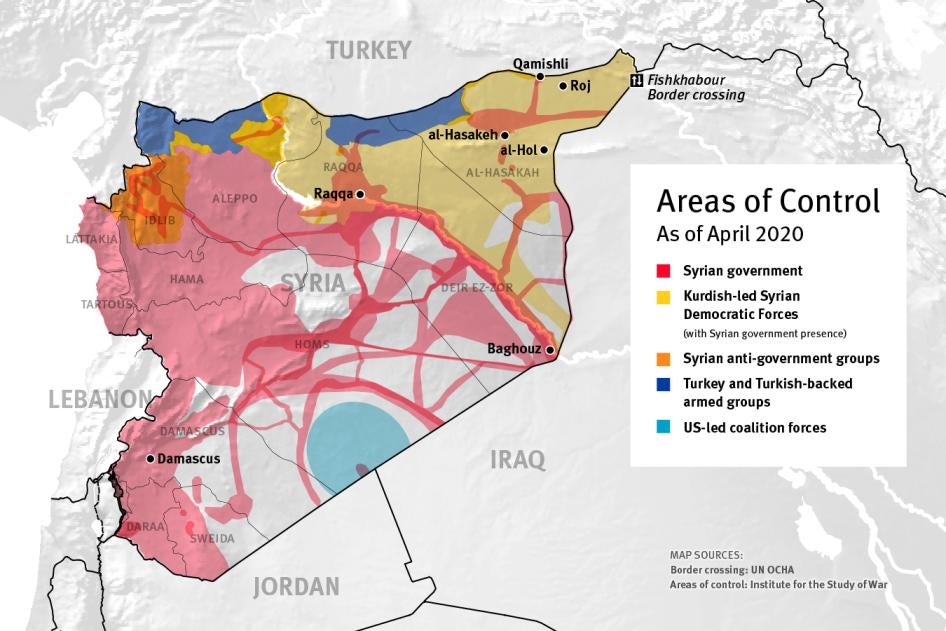

I. Detainees and Conditions

47 Canadians Including 26 Children

Since the fall of the Islamic State (ISIS) in Syria in 2019, the regional, Kurdish-led authority called the Autonomous Administration of Northeast Syria has been detaining some 100,000 ISIS suspects and family members in prisons and camps throughout its triangle of territory bordering Turkey to the north and Iraq to the east. The detainees are guarded by the region’s main militia, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which is backed by the US-led Global Coalition Against ISIS, of which Canada is a member.[1] The SDF served as the main ground force against ISIS in northeast Syria. The SDF has no known prior experience in prison management.

Most of the detainees are Syrians and Iraqis, but the Autonomous Administration is also holding about 14,000 non-Iraqi foreigners from more than 60 other countries–8,000 children and 4,000 women in camps and about 2,000 men and boys in prisons.[2] At least 47 Canadians—8 men, 13 women, and 26 children from 17 families—are among them, according to Alexandra Bain, the founder of Families Against Violent Extremism (FAVE), a Canadian non-profit organization that is helping families try to repatriate their loved ones.[3]

The two oldest Canadians are in their late 40s and the youngest is a 1-year-old infant.[4] The oldest Canadian child is a 17-year-old boy detained in a northeast Syria prison, according to Bain.[5] The other children are detained in camps—24 in tents with their mothers and one, 5-year-old orphan Amira, in a center for unaccompanied children.[6] Eighteen of the children are 6 years of age or younger and were born in Syria, Bain and family members said.[7]

Three dozen Canadians surrendered in February and March 2019 to the SDF during the fall of Baghouz, a town in eastern Deir al-Zour governorate that was ISIS’s last stand in Syria, Bain said.[8] Eleven others, including seven children, were detained earlier, some since 2017, Bain and family members said. At time of writing, the government of Canada had yet to bring even one of its detained citizens home.

Like the other foreigners, none of the Canadians has been charged with any crime by the Autonomous Administration. Nor have the Canadians been brought before a judge to review the legality and necessity of their detention, making their continuing captivity arbitrary and unlawful. Their detentions without judicial review also amount to a form of collective punishment, particularly for suspects’ detained family members.

Nearly all the adult detainees come from the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec. One man, Jack Letts, was raised in England and was a dual British-Canadian national until April 2019, when the UK revoked his citizenship for traveling to Syria in 2014.[9] At least three other Canadian adults had dual citizenship or the potential to obtain a second nationality, but lacked strong ties to their second country, according to FAVE and family members.[10]

At least five of the children were born to one foreign as well as one Canadian parent. Under Canadian law, children born abroad are Canadian citizens provided that at least one of their parents was a Canadian citizen at the time of their birth.[11]

Five Canadian children, all young, have medical conditions—two have asthma, one has neck tumors, one is anemic, and one is autistic—Bain and family members said.[12] Human Rights Watch is not able to independently verify all of the detainees’ health conditions. Some of their fathers are imprisoned but most are believed to be dead.

One Canadian man, Mohammed Khalifa, is a suspected ISIS propagandist and the reported narrator of Flames of War, a 2014 ISIS video that showed captured Syrian soldiers digging their own graves before being executed by gunfire.[13] Another, Mohammad Ali Saeed, posted horrific pro-ISIS messages on social media soon after arriving in Syria in 2014 and said he had worked as a sniper trainer, but told Human Rights Watch he became disillusioned and had “pretty much stopped showing up at work.”[14] At least three detained Canadian adults have struggled with various mental health conditions and allege they were imprisoned by ISIS for disobeying or trying to leave the group, their family members said.[15]

While Human Rights Watch cannot confirm the veracity of detainees’ statements, many of the detainees told us or their families that they regretted traveling to Syria soon after arriving there but once under ISIS rule could find no way out. One woman, a mother held in a camp with two young children born in Syria to her Canadian husband, who is detained in a northeast Syria prison, told Human Rights Watch:

I thought, “Now I’ll be able to practice my religion and cover my face without being harassed the way I am at home.” I heard there was bombing and stuff but I didn’t think I’d be living under it. But then I got here and realized how dangerous it was. My husband became disillusioned, too. A year ago, we found a smuggler to take us out. We wanted to start over. But then Kurdish [SDF] forces took us. [16]

The identity papers the Canadians had were confiscated by ISIS or, upon capture or surrender, by the SDF. Children born in ISIS-held territory had only ISIS birth certificates at most, leaving them without any without official documents to verify their nationality.

Human Rights Watch did not receive a response from Global Affairs Canada or Public Safety Canada—the government’s foreign office and national security agency, respectively—to its written requests for the number of Canadian men, women, and children detained in prisons or camps in northeast Syria. Global Affairs and Public Safety also did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s request for information on how many detained Canadians the government considers to be high security risks, or whether it considers any of them to be victims of ISIS. In addition, Global Affairs and Public Safety did not respond to requests for information on whether the government has pressed detaining authorities in northeast Syria to provide judicial review of the detentions of Canadian citizens.

In a letter to Human Rights Watch in June 2020, Foreign Affairs Minister François-Philippe Champagne cited security concerns for not providing such details.[17] Public Safety Canada did not reply.

Dire Conditions in Camps and Prisons

The conditions of detention for Canadians and other ISIS suspects and family members in northeast Syria are appalling and, in many cases, inhuman and life-threatening. In prisons for men and boys converted from former schools and government buildings, overcrowding is severe and medical care is grossly inadequate, according to Human Rights Watch interviews and media reports. Al-Hol and Roj, the two open-air camps detaining women and children, are locked, encircled by barbed wire, and heavily guarded by SDF and local police known as the Asayish. Conditions in the camp annexes for non-Iraqi foreigners are particularly harsh.[18]

The illness, filth and overcrowding in the camps and prisons have created a prime environment for the spread of Covid-19 and are increasing the despair of detainees and their families.

Since Covid-19, “Jack's life is more at risk than ever before,” wrote Sally Lane, the mother of Jack Letts, a Canadian detained in one of the northeast Syrian prisons, in an email to Global Affairs. “Is the government of Canada going to allow our son to die in prison in NE Syria?”[19]

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet in March called on governments to take urgent action to prevent Covid-19 from “rampaging through places of detention,” calling the consequences of neglect “potentially catastrophic” from a health perspective as well as risking “a boomerang effect on the global community's efforts to counter terrorism in the region.”[20] The UN Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture called on governments to “reduce prison populations…wherever possible by implementing schemes of early, provisional or temporary release.” The UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in April urged all detaining authorities to immediately release children in detention, including those held in relation to armed conflict, “who can safely return to families or an appropriate alternative” including members of extended families.[21]

At time of writing, only six cases of Covid-19 had been reported in northeast Syria, one of them fatal.[22] None involved camp or prison detainees. But the numbers could be far higher as testing for the coronavirus in northeast Syria is scant.

In April, the Global Coalition Against ISIS said it gave hygiene and medical supplies to detention facilities across northeastern Syria, including hand-washing stations, disinfectant wipes, face masks, and examination gloves.[23] The UN World Health Organization has also sent supplies including personal protective gear to al-Hol camp and aid groups have launched awareness campaigns in al-Hol.[24] But officials from the Syrian Democratic Council, the Autonomous Administration’s highest political authority, called the supplies insufficient.[25] And three Canadian women detained separately in Roj and al-Hol said they had seen no sign of most Covid-19 supplies.

“Not even for their few medical staff,” one woman wrote in reference to masks in one of several text messages from Canadian detainees shared by FAVE with Human Rights Watch. “Pets in Canada get more [medical] treatment than us,” wrote another. “For days we don’t have doctor. No[t] even a nurse sometimes.”[26]

The one clinic inside the foreigners’ annex has been closed for months. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has a field hospital “but you don’t get access to them unless you are dying,” said “Charlotte,” a Canadian detainee. “There are [northeast] Syrian medical teams with mobile vehicles but their supplies are really low. Sometimes they don’t even have paracetamol.”[27]

Charlotte laughed when asked about social distancing:

Everybody is basically mingling with each other. It really blows my mind. They don’t give us any masks or gloves. The only thing they did do, they didn’t call it [a] Covid [response], but they put laminated papers on the water tanks saying, “Protect yourself and wash your hands.” That’s it. It’s really scary.[28]

On April 30, the International Rescue Committee warned that in al-Hol, the larger of the two camps holding about 65,000 people, “There is absolutely no way for people to practice social distancing” given the population density.[29]

The embattled Autonomous Administration has repeatedly issued appeals for more foreign funding, warning that it lacks the resources to properly care for the detainees without further assistance.[30]

Further compromising sanitation and the well-being of detainees, al-Hol camp and the prisons for ISIS suspects in al-Hasakeh governorate have suffered intermittent water shortages since neighboring Turkey, which invaded areas of northeast Syria in October 2019, began periodically interrupting pumping at a water station serving 460,000 people in areas controlled by the Autonomous Administration.[31] Restrictions on aid deliveries from Damascus, the Syrian capital, as well as through the neighboring Kurdistan Region of Iraq are preventing urgently needed medical supplies and personnel from reaching northeast Syria, including to protect against the Covid-19 pandemic.[32]

The Autonomous Administration did not respond to requests from Human Rights Watch in May and June for updates on conditions in the camps and prisons. In his letter to Human Rights Watch, Foreign Affairs Minister Champagne wrote that Canada has spent more than Canadian $333 million (US $245 million) in humanitarian assistance in Syria, but did not say how much, if any, went to the prisons and camps holding Canadians.[33]

Camps: Overflowing Latrines, Preventable Deaths

During three visits to al-Hol camp in June 2019, Human Rights Watch found women and children living in tents that collapsed in strong winds or had flooded with rain or sewage, and saw worms in the water that children were drinking and pouring over their heads to keep cool. The rations did not include fresh food, even for children. Latrines were overflowing, garbage littered the grounds, medical care and basic provisions such as diapers and sanitary towels were insufficient, and respiratory and gastrointestinal infections, as well as child malnutrition, were rampant.[34] Those conditions continued at time of writing, aid workers and detainees said.[35]

“Kids are suffering from bouts of diarrhea and vomiting,” Charlotte told Human Rights Watch. “I think it has to do with the water in the tanks. They are putting a lot of chlorine in it, but the [camp] kids, they throw diapers inside the tanks. They have nothing else to do.”[36]

Fires caused by cooking and heating fuel periodically sweep through tents and are sometimes deadly.[37] Wild dogs roam the grounds at night and children have periodically fallen into open pits and cesspools. Ten camp residents told Human Rights Watch in June that a young boy had drowned days earlier in an open cesspool; camp officials denied any deaths but the Kurdish Red Crescent reported that at least 517 people, 371 of them children, died in 2019 in al-Hol, the larger camp, many from preventable diseases.[38]

“Extreme weather, burning tents, threats … little food/clothing, zero sanitation or health safety, disease,” Canadian detainee Kimberly Polman wrote in a letter signed by 10 detained Western women. “We survived ISIS, we were the lucky ones. … But can we survive the camps?”[39]

One Canadian woman shared text messages with Human Rights Watch from her sister-in-law that were increasingly filled with despair:

It's horrible here. When we have water, sometimes the water's clear. Sometimes it's green. Sometimes it's yellow. We're freezing. We’re sleeping in tents… Our tents get flooded."[40]

“Kayla” described a phone message from her adult daughter in December in which she was “crying hysterically”:

She said the conditions are devastating. She was sick with diarrhea and a rash on her neck. She said a disease is affecting all the children—sores on their bodies, their hands and everything, it affects their liver.[41]

The camps also lack schools and playgrounds although two-thirds of detainees are children.

Violence and Threats

Insecurity is rife, with violence periodically breaking out between detainees who still support ISIS and those who do not, as well as between detainees and guards from the SDF, which suffered massive casualties fighting ISIS.[42] Some female detainees have said they face threats of sexual violence. One woman said her adult daughter told her a guard was threatening detained women with the words, “We’re going to do to you what ISIS did to the Yezidis”—a reference to ISIS kidnapping, raping, and committing apparent genocide against members of the Yezidi religious minority.[43]

At al-Hol camp, some women in the foreigners’ annex reportedly remain ISIS loyalists and lead a local morality police force—al-Hisbeh—and have murdered at least two women for “immoral” behavior.[44] Human Rights Watch has previously documented how Hisbeh and other ISIS members policed women’s behavior including through physical abuse in ISIS-controlled territory.[45] Five women interviewed by Human Rights Watch at al-Hol camp, including one Canadian woman, said they feared being harmed by Hisbeh because they were considered moderates or had expressed remorse over joining ISIS.[46] A second Canadian woman expressed the same fears to her family in Canada.[47]

In June 2019, a 14-year-old girl was found murdered in her tent in al-Hol camp. Camp authorities said she was killed by camp hardliners for refusing to wear the hijab. [48] One Canadian woman wrote to the Canadian government through a family member that she and several other Western women were on the Hisbeh “kill list” because they had expressed remorse over joining ISIS.[49]

Detainees are terrified that the fighting in northeast Syria—involving the US-backed SDF, troops from the US, Turkey, Syria and its ally Russia, as well as various militia and remnants of ISIS—could spill into the camps or prisons. In October 2019, Turkish shelling hit a prison for ISIS suspects and the Ain Issa camp for family members of ISIS suspects.[50] They also fear capture by the forces of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, whose prisons are notorious for torture, mass disappearances, and deaths.[51]

In June, the Autonomous Administration announced that in conjunction with Global Coalition Against ISIS, its security forces began collecting the biometric data of women in the camps in as an effort to officially register them, identify detainees who are security threats, improve living conditions, and “facilitate coordination with the countries whose nationals reside in the camp and urge them to assume their responsibilities towards their citizens.”[52]

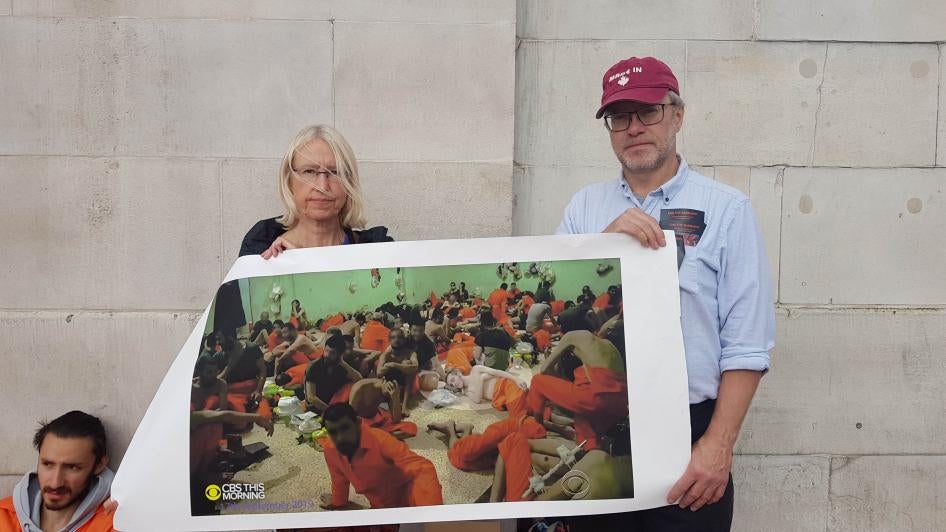

Prisons: Inhuman Overcrowding and Deaths

At least three prisons in northeast Syria holding the 2,000 foreign male ISIS suspects, including at least four Canadians, are severely overcrowded, with prisoners packed so tightly into cells that they cannot lie down without touching each other, according to Human Rights Watch interviews with eight people who had visited the prisons or had knowledge of the conditions.[53] Disease and malnutrition are widespread and medical care is grossly insufficient, they said. [54]

Between mid-2019 and early 2020, well over 100 and possibly several hundred prisoners died in the two largest prisons, Ghweran and al-Shaddadi many from lack of medical care according to two knowledgeable sources.[55] The death rate was highest in 2019, they said—a time when the prisons were flooded with detainees freshly wounded from the fall of Baghouz. Together those two prisons, both in al-Hasakeh governorate, hold an estimated 7,500 Syrian and foreign ISIS suspects.

The prisoners include more than 100 children, all boys, two interviewees told Human Rights Watch.[56] Two journalists reported seeing child prisoners as young as 9.[57]

At Ghweran, a former school that holds about 5,000 detainees including at least two Canadians, four interviewees described seeing cell upon cell packed with bone-thin prisoners, many with amputated limbs.[58] Many of the men wore thin orange jumpsuits similar to those the US military made Al-Qaeda and Taliban suspects wear at the Guantánamo Bay prison in Cuba, or clothes that were in tatters, the interviewees said. Each cell had only one, partially walled-off latrine, producing a gag-inducing stench, they said.[59] One interviewee told Human Rights Watch:

The odor was horrible. It was everywhere. It was an awful mixture of everything—toilets, sewers, and human beings. There are around 100 men in each cell with no windows. They eat there, they do their business there, and they sleep there. … It was shocking to see men of all ages together on the floor with no room to move. They were so close it was as if they were stuck together. … I can’t imagine what psychological state you would be in if you spent months in that cell.

They were wearing sandals. They had small, thin blankets and slept on thin mats on the floor. They were shivering in their cells. Some of the prisoners looked so weak, like they didn't have an ounce of energy.[60]

At least 100 prisoners at Ghweran are suspected of having tuberculosis and at least two detainees have died from the disease, but prison authorities lack sufficient medicine to treat them, three interviewees told Human Rights Watch.[61] Other prisoners had infected limbs or urgently needed replacement colostomy bags to collect their body waste, two interviewees said.[62] Lice and scabies were widespread in the prisons, three interviewees said.[63]

Anthony Loyd, a journalist with the Times of London, said he saw similarly dire conditions when he visited a hospital ward in one of the prisons in October 2019, holding about 450 detainees seeking treatment. “Several prisoners had multiple amputations and I saw one with his intestines hanging out beneath a bloody dressing,” he said.[64]

For much of their incarceration, prisoners have had no access to outdoor areas and were unable to communicate with family members, five interviewees said.[65]

One interviewee told Human Rights Watch that in Chirkin prison in Qamishli, where at least two Canadians are held, a detainee alleged that the overcrowding forced detainees to remain in almost the same position from 8 a.m. to midnight, and that his cell had a single latrine for at least 80 prisoners. In warmer months, the prisoner said, detainees were allowed outside only exceptionally and were kept inside if they misbehaved, and in winter, they did not go out at all.[66]

Three of the interviewees saw or spoke with three different Canadian prisoners.[67] Human Rights Watch separately interviewed a fourth Canadian prisoner in northeast Syria in June 2019 and reviewed a transcript and audio clips of a phone call made in January 2018 by a fifth Canadian, Jack Letts, to Global Affairs Canada.[68] All of the prisoners spoke within earshot of guards or other prison officials and most did not want to describe their treatment in detention.

“Please get me out of this place,” Letts begged in his call from Chikrin prison to Global Affairs. “Are they going to send us to Guantanamo? Are they going to kill us?”[69]

In the call, Letts said he was held in solitary confinement soon after his detention in 2017:

I spent 35 days in a room that is slightly taller than I am, and about half that wide, with no toilet, no nothing. I started to go insane and talk to myself. I thought dying was better than my mother seeing me insane so I tried to hang myself.[70]

Under UN minimum standards for humane treatment of prisoners, solitary confinement for more than 15 days is strictly prohibited and may amount to torture or other inhuman treatment.[71]

In an interview with a UK journalist and texts to his parents shortly after his detention, Letts had said he was tortured after his capture.[72] Asked about the allegation by a Global Affairs Canada official during the phone call, Letts spoke haltingly and sounded scared:

To be honest, how can I say this? I can’t—in a situation like this I can’t explain to you everything that has happened, do you know what I am saying? But please understand me, without my having to say it, that any place other than here is where I want to go.[73]

At the time of the call, Letts said, he was held in a room with 30 other prisoners that was only large enough for eight beds. He said he had not seen a doctor for seven months and had only received medication once despite health problems including acute, recurrent kidney pain.

One interviewee described the despair of two Canadian prisoners in Chirkin:

They are so isolated. No one comes to see them. This is what came out more than anything else. They want news from their family. [Name withheld] said, “I don’t even know if my mom knows if I’m still alive.[74]

On March 29, 2020, a riot broke out in Ghweran prison.[75] Video from inside the prison showed detainees raising a blanket on which they wrote a message in Arabic calling on the Global Coalition Against ISIS and unnamed “international and human rights organizations” to inspect the prison conditions.[76] The prisoners were demanding improvements including addressing over crowdedness, effective medical care, communication with family members, and clarification of their legal status, two interviewees told Human Rights Watch.[77] Prisoners at Ghweran staged a second riot for several hours on May 3.[78]

In April, the Autonomous Administration announced it was forming a committee to review the cases of all detainees in northeast Syria to assess their conditions—including “whether the prisoner has died” and whether they need to remain in custody—as well as to share information about them with family members.[79]

II. Case Studies of Eight Canadians

One is a 5-year-old orphan who was found on a roadside. Two are men who claim they were imprisoned first by ISIS, then by anti-ISIS forces, and one says he was tortured in SDF custody. Two are toddlers whose fathers were killed in Syria. A sixth is a woman who was widowed twice. A seventh says she was raped in an ISIS prison. An eighth is a mother who needs medicine for her two sick children. Following are eight case studies of Canadians detained in northeast Syria.

Amira: Stranded Orphan

Amira, who was 5 at time of writing, was found by a passerby in early 2019, wandering alone on a road leading from the rubble of Baghouz, her uncle “Karim” in Canada told Human Rights Watch. Amira told the passerby that her parents and all three of her siblings were killed in an airstrike. She ended up in the care of a stranger in one of the camps for women and children related to ISIS suspects in northeast Syria. A nongovernmental organization circulated a photo of Amira with her hair in braids and a fresh scar on her forehead that in mid-April found its way to Karim.[80]

Karim told Human Rights Watch that he immediately recognized Amira as his niece from photos that her parents had periodically emailed since her birth in Syria. Karim said he also made contact with other camp detainees who told him they recognized Amira and said she had named her dead parents and siblings, confirming her identity. Karim immediately contacted Global Affairs. He begged officials there to bring Amira home, offering to adopt her.

Three Canadian members of parliament, including Karim’s MP, have written to the ministers of foreign affairs and immigration to press the government to bring Amira to Canada.[81] Sixteen UN independent human rights experts have also called on Canada to urgently repatriate Amira and said repatriation of child citizens trapped in northeast Syriawas “a humanitarian and human rights imperative” for UN member states.[82] But at time of writing, Canadian authorities had yet to take the necessary steps to repatriate Amira or to help Karim do so himself, despite initial indications that they would help.

“Right now we've qualified it as too dangerous for Canadian officials to go into Syria and into those refugee camps,” Trudeau told CTV, Canada’s largest private television network, when asked in December 2019 why the government had not repatriated Amira.[83]

Global Affairs’ responses are “extremely frustrating,” Karim said. “I'm concerned for my niece's well-being physically, emotionally, mentally. I'm scared that I might lose her. She doesn't have anyone to watch [over] her.”[84]

Canadian officials said they could not help repatriate Amira until they knew where she was living inside the sprawling al-Hol camp but offered no assistance in finding her, Karim said, leaving it to him to persuade local authorities to track her down. “They said, ‘We need to know her exact location before we do anything. But they wouldn’t even help me find her,” he said. Eight months passed before the Autonomous Administration informed Karim that it had found Amira living in a tent with a woman detainee who was acting as her informal caregiver.[85]

At first, Karim told Human Rights Watch, “They said, ‘Hey, just get her to a border. And once that’s done, we can work on it.’” But every time he contacted Global Affairs, they retreated further from their early offers to assist. When Karim told Global Affairs he was working on possible ways to get Amira to the border, for example, “They started saying, ‘Well, do we really know it’s her? We may need DNA testing.’” Because Global Affairs had already told Karim that it was too dangerous for Canadian officials to travel to northeast Syria, Karim offered to go conduct the tests himself.

However, Global Affairs would not tell Karim what kind of DNA test they would accept and said he needed to ask Immigration Services. When he asked his Global Affairs case worker if she could give him an Immigration Services contact, the response was, “No, just call the 1-800 number.” When Karim finally reached someone at Immigration Services, he said, “I was just ignored. They said, ‘This is a Global Affairs issue.’ … It just goes back in circles.”

In December 2019, Karim, working through networks he developed without the assistance of Global Affairs, achieved a small victory when the Autonomous Administration agreed to move Amira to a center for unaccompanied children run by a humanitarian organization at the edge of one of the camps.[86] That month, an aid group arranged for him to have a video call with his niece for the first and only time. Karim told Human Rights Watch that Amira appeared to have an untreated tooth or gum infection that she developed before entering the center: her cheeks were so swollen that she couldn’t close her mouth.

In February, Karim traveled to northeast Syria in a failed quest to evacuate his niece. He was able to meet with Amira for a little over an hour inside a shipping container converted into an office:

I hugged her. She just sat there on my lap… I showed her pictures of her grandparents and other family members. I told her, “Everybody misses you, everybody loves you.” She knew who I was and that she’s from Canada.[87]

Amira’s health appeared to improve at the center, Karim said—her cheeks were no longer swollen and the center was treating her for asthma. But Karim was struck by how small and frail his niece looked: “If I didn’t know her, I would have thought she was two years old. Her hair is really thin. It didn’t look like she was getting proper food [before entering the center]. She looked like she weighed thirty-five pounds.”

When he arrived in northeast Syria, Karim again offered to conduct DNA testing to establish family ties and prove Amira’s right to Canadian citizenship. Global Affairs initially responded by telling Karim he could do so but did not provide any guidance. After his meeting with Amira in Syria, however, Global Affairs suddenly dropped the DNA requirement and said it would officially recognize Amira as a Canadian.

While in northeast Syria, Karim also requested permission from the Autonomous Administration to bring Amira back with him to Canada. But Dr. Abdulkarim Omar, co-chair of the administration’s foreign relations commission, said Canada must first send an official delegate to northeast Syria to sign repatriation documents, following the same protocol that the Autonomous Administration required of other countries. Canada could designate a humanitarian aid worker or other representative in lieu of a government official to oversee Amira’s transfer, the official said. Amira could then be escorted out of the camp to be met by Canadian officials in the neighboring Kurdistan Region of Iraq, where Canada has a consulate.

“It’s very easy to get Amira out,” Karim said the official told him. Karim relayed that information to Global Affairs officials, but at the time of writing, they had yet to name or send a delegate to bring her home.

Jack Letts: No Action on Alleged Torture

When Jack Letts was captured and imprisoned by the Kurdish-led SDF in Syria in May 2017, he called home to the UK in relief. “The Kurds are being good to me,” Letts, who was then 21 and a dual Canadian-UK national, said in an audio message to his parents. “… Mum, I think the whole process of handing me over [to come home] may be starting.”[88]

Within weeks, however, Letts’ audio messages had taken an ominous tone. “They threatened me with torture,” Letts told his parents in a June message. “They say they’ll put me in a box.”[89] A week later, he left a message saying that: “Yesterday I had… a mental breakdown. … I actually went insane.”[90]

By July, Letts sounded desperate, saying he had been tortured and suggesting his captors may have used electric shocks:

My health situation has got much worse. Now they don’t bring me food. There’s no such thing as going out any more. And then they punish you. I’ve actually been tortured, intimidated. … I’m scared of electricity. Mum, I’ve actually been tortured.[91]

After that, Letts’ parents said, the messages stopped.

Letts has surfaced periodically in media reports since then and even made a call to Global Affairs Canada in January 2018 in which he repeatedly begged an official for help.[92] But Letts’ parents, John Letts and Sally Lane, both dual Canadian-UK nationals, told Human Rights Watch that Global Affairs Canada appears to have taken no action on their pleas to investigate their son’s allegations of torture and other ill-treatment or to get him out of a northeast Syria prison.

“Global Affairs Canada says the statement of torture is credible but not easily provable,” John Letts said.[93] The UK reportedly chose to disregard the torture allegations.[94] The Autonomous Administration has denied any mistreatment.[95]

In his 20-minute call in January 2018 to Global Affairs Canada from Chirkin prison, Jack Letts called his conditions “terrible” and repeatedly begged Canada for help:

Please get me out of this place. … Just get me out of here as soon as possible. I want to come to Canada. … Can you help me? Do you have any idea how long I might stay in this place? … I am going insane.[96]

Letts said he was held for 35 days in solitary confinement, during which time he tried to hang himself. At the time of his call, he said, he was among 30 prisoners sharing a cell that was only large enough for eight beds, and that he had been trying unsuccessfully for months to receive medical care for acute kidney pain.

He sounded scared and did not reply directly when the Global Affairs officer on the call asked him about his earlier allegations of torture:

“To be honest, how can I say this? I can’t—in a situation like this I can’t explain to you everything that has happened, do you know what I am saying? But please understand me, without my having to say it, that any place other than here is where I want to go.”

Voice of other people can be heard in the background from where Letts is speaking, making it clear he was not speaking out of earshot.

“We’ll try to help you,” the Global Affairs official tells Jack Letts, but adds that the government’s abilities are limited by its lack of consular presence in Syria.

John Letts told Human Rights Watch that he and his wife had first reached out to Global Affairs in 2017, after their son’s capture:

The first reaction was, “We’ll help you, this is a Canadian, this is outrageous.” But then they started to email back saying, “We can’t seem to find a telephone number for the Kurds [the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration in Northeast Syria].” We said, “Here is the number for their ambassador in London, here is the number for their ambassador in Berlin.” They said, “Well, they’re not answering their phone but we’ll keep trying.” Then it was, “We are struggling because they [the Autonomous Administration] are non-state actors, we can’t figure out if they are holding him.” We said, “We know they are, here is the number of the prison governor [authority].”

Then it was, “Well, we’re talking to them but we can’t talk to you about it because we need your son’s permission to talk about him to you.” We said, “Well, we can’t get that permission to you because he is in solitary confinement.” I then said, “We are his parents and can act on his behalf.”[97] Then they said, “Oh, we can’t tell you about conversations with foreign governments.” We said, “But you yourself said these [Autonomous Administration] officials aren’t from a government, they are non-state actors.”[98]

In a meeting in Ottawa in April 2018, John Letts said, Global Affairs told him that it was too dangerous for Canadian officials to travel to northeast Syria to retrieve his son. The officials said they had arranged for Jack Letts to receive medical care, but John Letts said he had no confirmation that his son had received any.[99]

In March 2020, Jack Lett’s mother emailed Global Affairs asking if the government could confirm that her son was still alive. A Canadian consular officer emailed back in March and again in April that Global Affairs had established a communication channel with authorities in northeast Syria but that those authorities “have not provided us with any specific information regarding your son’s circumstances.”[100]

“In other words, they can't guarantee whether Jack is alive or not,” his mother told Human Rights Watch.[101]

As a child, Jack Letts was diagnosed as with an obsessive-compulsive condition, and in 2014, at age 18, he left the UK in 2014 for a holiday in Jordan, his father said. He went to Syria later that year. In 2016, a UK deradicalization counselor told The Guardian, Jack Letts repeatedly told him in Facebook exchanges that he wanted to come home, even if it meant serving prison time, and discussed escape routes. But, the counselor said, the UK Home Office took him off the case that year as part of a new approach of disengaging with citizens who had traveled to Syria.[102]

Jack Letts had told his parents for months before his capture that he had been trying to leave Syria, John Letts said. In prison interviews with British media, he admitted to living under ISIS but denied being a member and said the group had imprisoned him three times for opposing its practices.[103] In 2019, the UK government revoked his UK citizenship on suspicion of ISIS links. He has not been charged with any crime in the UK, northeast Syria, or Canada.

John Letts, an organic farmer based in England, and Sally Lane, who lives in Canada, believe their son is innocent but accept that he may have to stand trial. “We just want him to have a fair trial. If he's done something wrong he should be punished,” John Letts said. He noted that his son has said publicly that he was willing to go to prison if he was found guilty.[104]

John Letts said the quest to get their son out of Syria has left him and Lane emotionally spent. In October 2017, the couple went on a weeklong hunger strike to press for their son’s return. In June 2019, a UK court convicted the pair of entering into a funding arrangement for the purposes of terrorism for sending £223 (US $286) to a family member in Lebanon that prosecutors said was for their son. They received 15-month suspended sentences.[105]

“Noor” and “Salma”: Failure to Recognize Citizenship

“Noor,” 3 years old, and “Salma,” 21 months old, were born in ISIS-held areas of Syria, each to a Canadian father and a foreign mother. In 2019, Noor’s father was shot dead by a sniper, and Salma’s father was killed in a coalition airstrike, according to the two girls’ Canadian aunts. For more than a year, the two aunts said, the toddlers have been detained in one of the northeast Syria camps with their mothers. The mothers’ home countries have made no moves to repatriate them or to recognize the children’s citizenship, and neither has Canada, they said.[106]

Since learning of the two girls’ detentions, “Basma” and “Lakia” have been asking Global Affairs to recognize their nieces as Canadian nationals, but they said they have gotten nowhere.

“She doesn't exist anywhere in the world right now,” said Basma, Noor’s Canadian aunt. “She's just a stateless child with no ID. We feel helpless because even if [Global Affairs] can't do anything, they're also not telling us what it is that we can do.” [107]

Basma and Lakia said they were not asking Global Affairs to bring their nieces to Canada at this time, and that they might never do so. They said they simply wanted to establish their nieces’ Canadian citizenship as a safety net should anything befall the girls’ mothers in the camps or should the girls be unable to obtain their mothers’ nationalities.

Lakia recalled her fears when Salma’s mother told her in September 2019 that Salma had Hepatitis A:

She was very, very sick. She was no longer getting out of bed. I imagined her, with Hepatitis A, lying down, no longer able to function with a one-year-old baby that needs to be taken care of. … Without medicine, or health care. If something happens to the mother, what happens to my niece?[108]

Basma and Lakia said that when they asked Global Affairs to recognize their nieces as Canadian, they were told they could not do so because they had no consular presence in Syria. When the two aunts asked Global Affairs what DNA tests they would accept if they arranged them on their own, the response was, “‘Oh, we don't know,’” Basma said. “It was just a whole mess.”

In November 2019, Basma and Lakia traveled to northeast Syria to see their nieces. On their very last day in the region, in early December, the Autonomous Administration let them visit the girls. The aunts had brought affidavits to northeast Syria drafted by a Canadian lawyer for their nieces’ mothers to sign that they could bring back to Global Affairs, attesting that the girls’ fathers were Canadian. But the morning of their visit with their nieces, their local guide told them that the Autonomous Administration would not let them obtain detainees’ signatures on documents absent permission from home countries—permission that they did not have and that Global Affairs had not told them they needed, they said.

Basma told Human Rights Watch she was shocked when she met Noor in the camp, finding her niece severely malnourished. Noor’s mother said the girl had suffered from diarrhea for four months:

My [3-year-old] son is exactly a month older than my niece. Lifting my niece in my arms, there was a clear difference in weight from my son. My niece was significantly lighter. Her face, her skin was so dehydrated. Her clothes were so thin, and I was wearing thicker clothes than her and I was cold. She was happy when I gave her chocolate, but there were no words that came with it.[109]

The aunts brought their nieces gifts—shoes for Salma, who had none, and a coat for Noor. But they have not sent them anything from Canada, because Global Affairs would not advise them whether they might be charged with support for terrorism, Basma said:

I knew that she didn't have any [fresh] food to eat. I knew that they were malnourished, and I couldn't even send a hundred dollars for food. It's not like they have a P.O. box where I could send mail and send clothes or whatever. I couldn't do anything.[110]

Lakia said she felt like the Canadian government “doesn’t really care”:

I'm having to fight the government for kids, for Canadian kids, for innocent Canadian kids. The children who didn’t decide to go there, who didn’t decide to be born there, they are victims. The Canadian government needs to realize that it should be a priority to stop creating victims and to create Canadian citizens.[111]

“Charlotte”: Automated Response from Global Affairs

“Charlotte” has been widowed twice since she and her husband, both Canadians, moved to Syria with their two young children in 2014. She was pregnant with her third child when she was detained by the SDF while fleeing Baghouz in February 2019 and gave birth in a hospital inside one of the camps later that year.[112]

In a telephone interview with Human Rights Watch in April, Charlotte expressed remorse over coming to Syria:

If I could turn back time, I wouldn’t be here. I just want to come back home. I want to give my kids a life like I had when I was growing up. I had such a good childhood. I feel so bad for my parents. My children are the only grandchildren that they have. I make a mistake, but I didn’t participate in anything that was done [by ISIS]. I was just at home with my children. Everybody makes mistakes, you know? It’s what you learn from them.[113]

Human Rights Watch is not in a position to gauge the veracity of Charlotte’s comments on her role in ISIS.

Dogs howled in the background during the interview. Charlotte said they were wild and ran through the camp in packs at night:

People dump their urine and feces and there is garbage all over the place. Dogs come and eat the Pampers [diapers]. There are probably hundreds of dogs in the camp. At night they go through the garbage and tear everything apart.[114]

Charlotte’s father, “Michael,” and her mother, “Beverly,” told Human Rights Watch that they had repeatedly contacted Global Affairs since 2017 to ask how they could bring their daughter and grandchildren back. Each time, “We got no reply except an automated response” that their letter was received, Beverly said. Michael and Beverly have repeated their appeals during their frequent calls to a case worker in Global Affairs but “she just takes the messages,” Michael said. The couple has even asked Global Affairs to simply tell them if they have no hope of ever receiving assistance, but they have received no answer to that request either, leaving them in a state of indefinite limbo, he said.[115]

Like the other family members interviewed by Human Rights Watch, Michael and Beverly said they had no idea that their daughter and son-in-law were planning to live under ISIS in Syria. They said Charlotte’s first husband, an engineer, left in 2014, telling them he had taken a job in the oil industry in Qatar, and sent for Charlotte and the couple’s two children a few months later. Soon after, Beverly said, they received a call from Charlotte saying all was well:

We were thinking everything was fine. But then we lost contact with her for close to ten months. Nothing. When she finally called again, she said she was in Qatar, that they were happy and had found a good life. I was questioning her, question after question. We wanted to go see the grandchildren. She said, “There is not enough room.” We said, “We can go to a hotel.” She said, “No, Mom.” She said, “Mom, please don’t ask me these questions.” Then in 2015, CSIS [the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service] came knocking at our door. They said they suspected [Charlotte’s husband] was a terrorist. I was in shock.[116]

After Charlotte’s Canadian husband died in 2016, “She finally did break down and tell me, ‘Yes Mom, I am in Syria,’” Beverly said. But Charlotte said that ISIS would not let her leave. Like most widows, she was told by ISIS to remarry. Charlotte’s second husband, an ISIS member from a European country, was killed three months after their wedding.[117] By then, she was pregnant again.

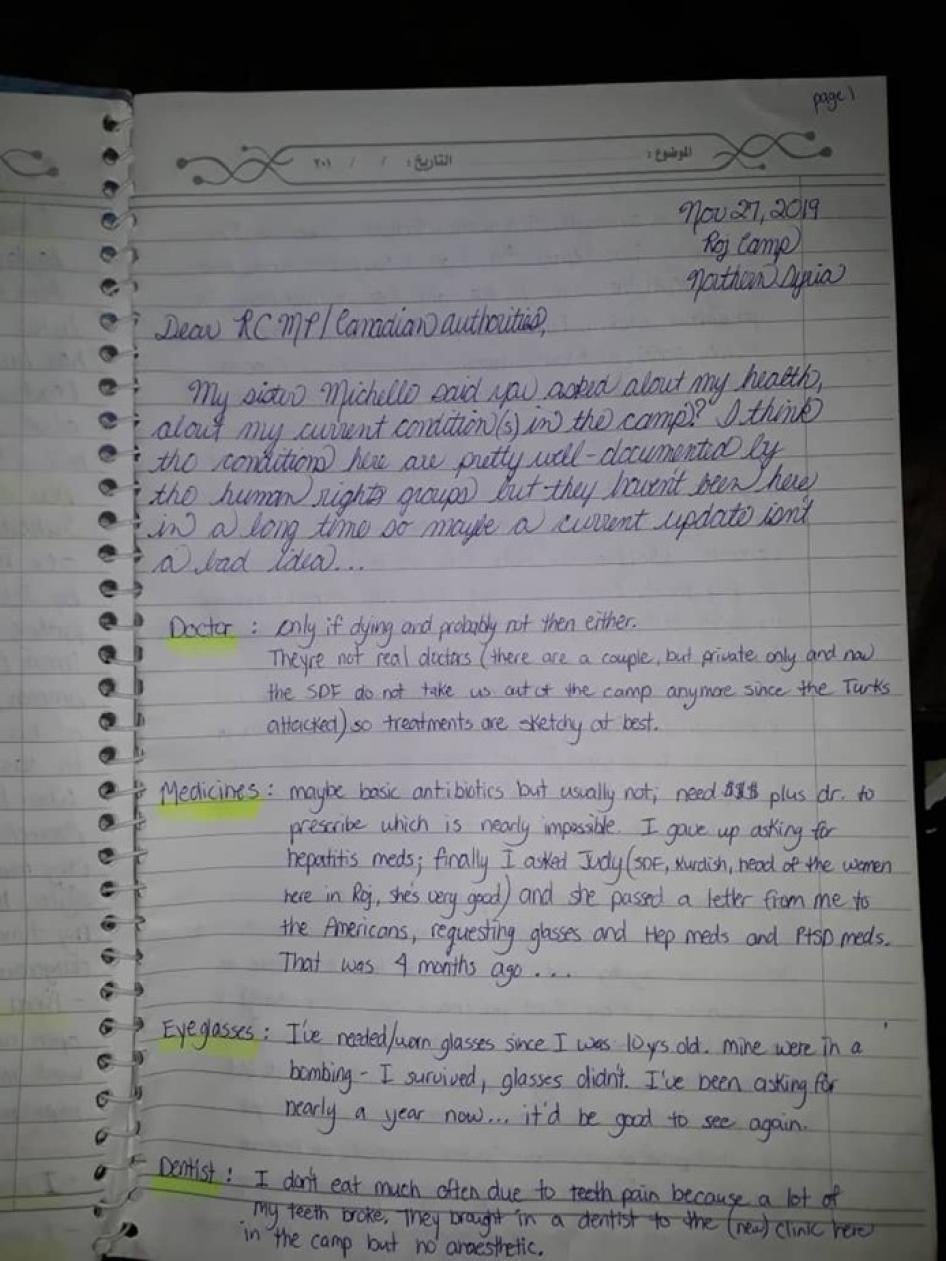

Kimberly Polman: Canada Will Not Even Confirm Detention

Kimberly Polman, 47, has written to Canada-based family members and the Canadian government describing abuses she endured after leaving Canada for Syria five years ago to become an ISIS nurse and marry an ISIS fighter, her need for medical care in an SDF-run detention camp, and her longing to come home. But Global Affairs Canada will not even officially acknowledge that Polman is detained in one of the northeast Syrian camps, her sister “Maryanne” said:

She has been very ill. She needs medication and has no money. She told me, “You have to be pretty much dead before you get to see a doctor in the camp.” I sent [Global Affairs] a picture of her ID card. That was months ago. It’s a camp-issued card. All they say is, “We are trying to establish contact with the Kurds [the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration] to see if she is there.”

Maryanne questioned how Global Affairs would have difficulty verifying her sister's identity or whereabouts. She noted that Polman told her she had been interviewed by intelligence agents from the US, UK and France—all allies of Canada—after she surrendered to the SDF in January 2019. Moreover, Maryanne added, it was CSIS that informed relatives in 2015 that Polman had gone that year to Syria, not Austria for a job as she had initially told them.

Maryanne described Polman as “totally traumatized” from nearly four years under ISIS and more than a year in a northeast Syria camp. A handwritten letter from Polman to “Canadian authorities,” sent to her family in October 2019 as text images, painted a grim picture of her condition:

Doctor [visit]: only if dying and probably not then either. … Medicine: maybe basic antibiotics but usually not. … Eyeglasses: I’ve been asking for more than a year now. …I’m constantly sick with infections. Currently I’m recovering from Hepatitis #4; I get it every 3-4 months, most likely from the water. In the camp there are/have been: TB, pneumonia, cholera, Typhoid fever, Hepatitis, desert fevers, kidney stones, unknown pulmonary (lung) infections, influenza, asthma, skin infections, snake/spider/scorpion bites.[118]

Polman also wrote that the was terrified of being threatened or killed by hardliners. “Please, bring me back to Canada,” she wrote. “Please, forgive me. Let me be who I am, a Canadian.”[119]

In subsequent communications, Polman has described the conditions as similar. In April, she said she had a kidney infection, a lung infection and hepatitis, Maryanne said.[120]

Polman is a dual US-Canadian citizen but spent nearly all of her life in Canada before moving to Syria. She grew up in a dysfunctional household with a father who struggled with addiction and was psychologically abusive, Maryanne said.

Just before Polman secretly left for Syria in 2015, she had lost her home. The Canadian government had placed her on permanent disability at the recommendation of a psychiatrist but the notification arrived just days after she left. An adult convert to Islam, Polman had met and married an ISIS member online who lured her to the so-called caliphate with promises of love and a nursing career, Maryanne said:

He told her all the good she could do. She always considered herself a self-fashioned nurse so she thought she could go over and help the women and children. She was looking for a sense of purpose no matter how misguided.

Soon after arrival, Polman contacted her family, confessed she was in Syria, and said she wanted out. “She was panicky,” Maryanne said. “She said it wasn’t what she was expecting and that her husband was very abusive and that he wouldn’t let her leave. Then we didn’t hear from her until June 2016. We thought that she was dead.”

When she finally resurfaced, Polman texted her family that her husband had put her in an ISIS prison in Raqqa for 10 months for being a “disobedient wife.” She said her captors raped her and gave her so little food that her body weight plummeted.[121]

Polman told family members that she still wanted out but that she was “watched all the time and you were killed if you tried to leave.” During the fall of Baghouz, she said, she had tried to continue caring for sick and wounded children but “these kids were dying. They had nothing to treat them with—no bandages or anesthetic or medication, no formula for the babies, nothing.”

In October, Polman wrote a letter addressed “To the United Nations” signed by 10 Western ISIS wives expressing remorse and offering to recount the horrors of their time in Syria as a way to deter others from joining extremist armed groups. Maryanne shared the letter with Global Affairs but did not hear back. “I guess they weren’t interested,” she said.[122]

“Asma”: Family Willing to Pay her Way Home

When “Asma” left Canada in 2014, the family had no idea she was leaving the country, much less headed for Syria to live under ISIS, her relative “Ghani” said. “The day she left, I even drove her to the subway station. She said she was just going to donate some clothes. I dropped her off and that was it.”[123]