Summary

Soon after the Rana Plaza collapsed in 2013 in the outskirts of Dhaka, Bangladesh, killing over a thousand workers, a top official from a global brand flew into Pakistan.[1] His sudden trip was sparked by the desperation to make up for orders his company had placed, and lost, with a factory destroyed in the Rana Plaza disaster. He concluded a business deal with a new Pakistani garment supplier and flew out within hours. Usual factory onboarding procedures were discarded. The fact that the global brand had previously rejected the supplier for “failing” social audits (inspections to check working conditions) did not matter. The brand’s business needs trumped workers’ rights. Lamenting the duplicity of the brand, a Pakistani garment supplier who followed this transaction and narrated its details to Human Rights Watch, said, “All this because he [the global brand representative] had to make up the order placed at Rana Plaza—and all ethics went out of the window. Everybody is like that.”[2]

The Rana Plaza disaster was a wake-up call to the world—1,138 workers died and over 2,000 were injured. It shone a light on the problem of death trap factories and poor government oversight. It also revealed much about how apparel brands do business and about their commitments to workers’ rights.

The nature of the apparel business is such that brands need to pay attention to market trends and consumer preferences that can change with dizzying speed. With the tremendous growth of online shopping, experts say global brands’ ability to churn out products quickly is key to success.

A maze of decisions underpins the development of each product before it hits the shelves. From forecasting consumer demand and planning; sales and marketing; designing products; selecting factories for manufacturing, monitoring them for social and labor compliance; and placing orders with and paying suppliers, numerous departments within a brand are involved in decision-making. Alternatively, some parts of these decisions may be made through agents. This complex web of decisions is generally referred to as a brand’s sourcing and purchasing practices.

This report is based largely on interviews with garment suppliers, social compliance auditors, and garment industry experts, including those with at least a decade’s experience sourcing for numerous global brands; hundreds of interviews with workers; and trade export data analysis for key producing markets from Asia. The report argues that brands’ poor sourcing and purchasing practices can be a huge part of the root cause for rampant labor abuses in apparel factories, undercutting efforts to hold suppliers accountable for their abusive practices. Because brands typically have more business clout in a brand-supplier relationship, how brands do business with suppliers has a profound influence on working conditions.

Brands can and should balance the twin goals of responding to consumer demands and protecting workers rights in factories that produce for them. This can only happen if they invest in a variety of human rights due diligence tools also needed to monitor and rectify their sourcing and purchasing and adopt key industry good practices. These steps will go a long way in discharging brands’ responsibilities articulated in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UN Guiding Principles) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment and Footwear Sector (OECD Due Diligence Guidance on Garments).

Poor Sourcing and Purchasing Practices

Low purchase prices and shorter times for manufacturing products, coupled with poor forecasting, unfair penalties, and poor payment terms, exacerbate risks for labor abuses in factories. Often, bad purchasing practices directly undermine efforts brands are making to try to ensure rights-respecting conditions in the factories that produce their wares. They squeeze suppliers so hard financially that the suppliers face powerful incentives to cut costs in ways that exacerbate workplace abuses and heighten brands’ exposure to human rights risks. Many brands demand their suppliers maintain rights-respecting workplaces, but then incentivize them to do the opposite.

Prices brands pay suppliers can undercut factories’ ability to ensure decent working conditions. In 2016, an International Labour Organization (ILO) global survey of 1,454 suppliers across different sectors revealed that 52 percent of apparel suppliers said brands paid prices lower than production costs. An industry expert with more than 25 years of experience sourcing apparel, footwear, and non-apparel products for multiple brands, told Human Rights Watch: “The pressure on sourcing teams and buyers is always about finding a better [lower] price [for production at a factory]. There are few times when the question is asked, ‘Well, if we do this, will we have compliant production?’” Suppliers who spoke to Human Rights Watch felt brands did not negotiate costs. Some raised concerns that brands do not even cost for increases in legal minimum wages. Suppliers and industry experts also raised concerns about heightened pressures where brands used agents to place orders.

The amount of time a brand gives a factory to produce its goods impacts the factory and its workers. One supplier told Human Rights Watch:

We are getting pushed more and more to reduce our lead times. Sometimes we have to confirm some short lead times without any security [buffer] in sight or any tolerance by the brand. If we don’t agree to the lead times, we might lose the order.

The 2016 ILO supplier survey revealed that only 17 percent of respondents across different sectors (not just apparel) believed they had enough lead time to produce goods.

Brands can exacerbate time pressures with poor forecasting, delays in providing necessary order specifications or approvals, and sudden changes to order volumes, throwing off a factory’s ability to plan regular and overtime work for its workers. The Better Buying Purchasing Practices Index for 2018, a third-party index developed based on anonymous supplier surveys, revealed that many delays occurred in the pre-production phases; respondents said that only about 16 percent of buyers (brands) met all agreed-upon deadlines in the product development and pre-production stages.

Brands can and should take fair responsibility for delays they cause. If they do not, and suppliers are left to absorb these costs on their own, it is often the workers who lose out and suffer most. Examples of brands that take fair responsibility for delays include those that have flexible delivery schedules, pay for air freight to transport products faster, or waive financial penalties. A combination of a brand’s manufacturing terms and management decisions influence how its representatives identify and take responsibility for brand mistakes. Detailed, written manufacturing contracts are not an industry norm. Where they do exist, they are often one-sided—many brands assume no written responsibility for delays or other mistakes made by them. Experts say that in some cases, unscrupulous brands unfairly charge discounts and penalties to suppliers as a way of cutting their own costs, knowing that suppliers do not have much leverage to push back.

Finally, brands often unreasonably delay payment to suppliers for the work that they do. The United Kingdom Prompt Payment Code, a set of voluntary standards and payment best practices, is a good example of the kind of approach businesses and regulators can take to stamp out such practices.

Key Labor Abuses

Brand approaches to sourcing and purchasing are not merely a threat to a factory’s financial bottom line. They incentivize suppliers to engage in abusive labor practices and in risky contracting with unauthorized suppliers as a way of cutting costs. This means that brand practices in these areas directly undercut their own efforts to insist on rights-respecting working conditions across their supply chains. Human Rights Watch spoke with seven auditors, each of whom had between five and twenty years of experience conducting social audits. Almost all said they felt they were not witnessing enough improvements in working conditions in factories, in part because the prices paid by brands for garments were too low, let alone supporting factories to remediate non-compliant practices.

It bears emphasis that the primary responsibility for abusive workplace conditions lies with suppliers themselves. But if apparel brands are genuinely committed to rooting abuses out of their own supply chains, they need to do everything within their power to ensure that their own business practices prevent and discourage, rather than incentivize, supplier abuses.

Even though some brands appear to be moving in the right direction, overall brand purchasing practices have proved to be intractable problems and continue to impact labor rights adversely, especially in relation to workers’ wages and working hours, and their contracts. Many factories are often hostile to unions and collective bargaining—key vehicles for improving workers’ wages and benefits—and this hostility is further deepened in an environment where brands do not use costing tools to account for the financial implications of labor and social compliance.

Overtime-related violations are an open industry secret. Factories hide the number of hours workers actually work to pass compliance audits and find innovative ways of bypassing overtime wage regulations. In Myanmar, for example, workers described how factories had “stolen minutes” from them. To avoid paying overtime wages, their “hourly” production targets were recalibrated where each “hour” was 45 or 5o minutes. In India, workers from a factory described how the factory compelled them to use up some of their paid leave during the factory’s low production season instead of paying overtime wages.

Similarly, factories often resort to casual contracts for workers to cut costs or in response to variations in brand orders. In Pakistan, for example, suppliers that Human Rights Watch spoke with said they were under tremendous price pressures and that many brands followed a price-bidding system. This intense price pressure creates an environment that allows abusive cost-cutting practices to thrive, rather than firmly arresting them. Factories hired workers through contractors to avoid making social security and pension contributions that would otherwise be legally required—a key cost-cutting strategy. In Cambodia, factories repeatedly use short-term contracts in excess of legally permissible limits, citing seasonal variations in brand orders.

In order to cut overtime costs, factories try to extract more work from workers using fewer minutes or hours. Human Rights Watch has consistently heard accounts of workers from different countries—Cambodia, Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, and Pakistan—about the pressure to work faster and without breaks. Some common methods of getting workers to produce more include restricting workers’ toilet breaks; trimming their meal breaks; squeezing “trainings” into lunch or other rest breaks so the “production time” is not lost; disallowing drinking water breaks and other rest breaks. The pressure to work faster has a gendered impact, especially given women workers’ needs for additional toilet or rest breaks during menstruation. Pregnant workers from different countries have told Human Rights Watch that they have found themselves targeted as “unproductive.” Workers have also recounted how line supervisors or other managers hurl verbal abuses at them to humiliate them and make them work faster.

Outsourcing production to smaller, low-cost units without brand permission is another method used by factories to cut production costs or meet production deadlines. Industry experts privy to unauthorized subcontracts told Human Rights Watch that brands purchasing practices can drive such outsourcing. They identified poor forecasting, brands’ failure to monitor factory capacity, the use of buying agents, absence of ordering time tables, last minute design changes, and poor prices among the purchasing practices deficits that catalyzed factories’ use of unauthorized subcontractors.

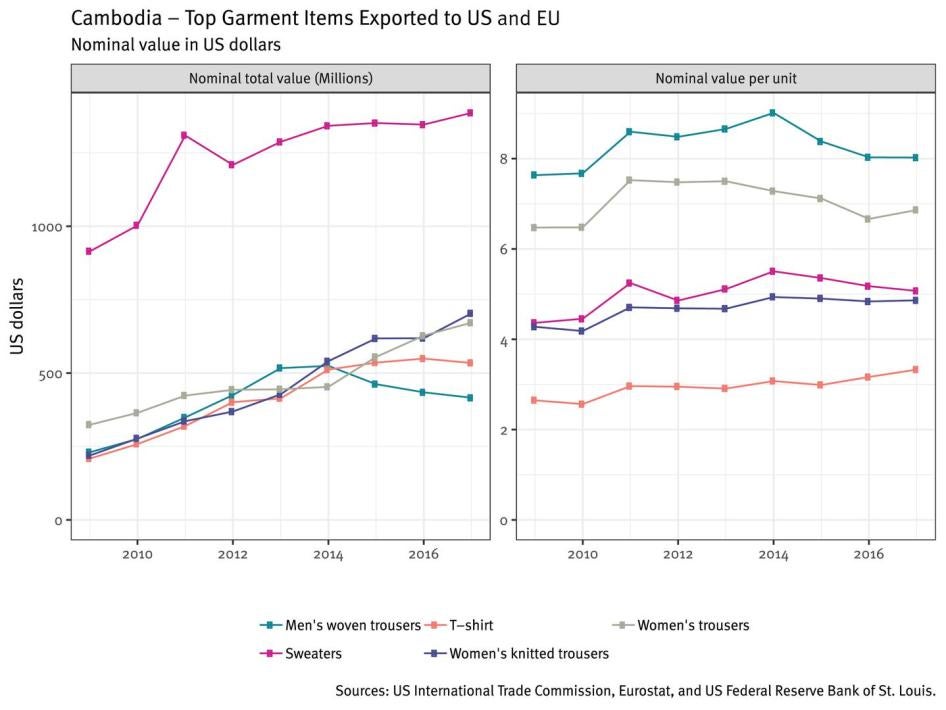

A prime example of growing unauthorized subcontracting is Cambodia. Even though statutory minimum wages went up, EU and US trade data shows that nominal apparel prices paid by international apparel brands for the top five products manufactured in Cambodia (by value) mostly dropped between 2014 and 2017 whereas in the same period, the government raised the monthly basic wage (that is without adding mandatory allowances) from US$100 to $153. Between 2014 and 2016, the ILO documented a spurt in the number of subcontractor factories from 82 to 244.

In 2016, Human Rights Watch physically mapped 45 subcontractor factories in Cambodia’s Kandal province with the help of workers. This was in addition to a few other subcontractor factories Human Rights Watch saw in Phnom Penh. Most of these factories were unmarked, making it difficult to even detect that the building housed a factory. In the few factories from where Human Rights Watch was able to interview workers from these subcontractor factories, Human Rights Watch found that the working conditions were worse: workers were hired on a casual basis on piece-rate wages, did not receive other legal benefits, and worked in factories without any health clinics.

Sourcing experts that Human Rights Watch spoke with, as well as suppliers, identified a combination of purchasing practices that further drove such factory practices. These include prices that do not adequately factor in labor costs, poor forecasting, huge departures from the projected volume of orders, delays in brands’ technical packs (documentation that provides complete information needed to make a product, including construction graphics and measurements, materials, sizing information) and approvals needed to begin bulk production.

Factories under price pressure also do not invest enough in making fire and building safety improvements. How brands do business with them influences their loan eligibility even where they want to make improvements. A study by the International Finance Corporation in Bangladesh underscored the links between brand purchasing practices and fire and building safety. Factories’ loan eligibility to make these financial investments was influenced by their ability to show strong business relationships and good cash flow, which directly depended on brand purchasing practices. The Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety specifically stipulated that brands have the responsibility to facilitate financing for remediation. Experts believe this resulted in a few brands using their purchasing practices to support financing factory repairs, but otherwise, did not bring about significant reforms on the purchasing practices front for all member brands.

Moreover, a range of other occupational health and safety concerns, including factories installing sufficient cooling mechanisms to maintain ambient working conditions, also depends on factories’ ability to make the necessary financial investments. Workers have described to Human Rights Watch the challenging circumstances under which they work, which hints at the cost-cutting methods used by factories. For example, workers have described dripping in sweat and working in unbearable heat levels, and with inadequate air circulation because of fewer fans or fans that just circulate hot air in a closed space.

Key Features of Effective Human Rights Due Diligence on Purchasing Practices

Brands have a responsibility to take measures to identify and stop, prevent, and mitigate risks that cause or contribute to human rights problems in their supply chains.

Brands—large and small—truly committed to workers’ rights should adopt and publish a policy on responsible purchasing practices and embed this across all internal departments through standard operating procedures, trainings, key performance indicators, and incentives tied to measures on social and labor compliance in factories.

Internal integration of policy should be combined with comprehensive contractual reform. Such reforms should ensure that contracts with suppliers accurately outline brand responsibilities to factor in labor and social compliance costs and production times. Contracts should outline brand responsibility to provide the supplier with complete and accurate technical details, brand approvals, consequences of brand delays, and business incentives for factories that comply with labor laws and collective bargaining agreements. This kind of contractual reform will help mitigate the power imbalance between brands and suppliers by transposing brand commitments into contracts. It will also help mitigate brands’ exposure to heightened human rights risks arising from brand actions and omissions, and allow a brand to demonstrate through legal certainty for its suppliers that it is committed to assuming a fair share of its responsibility to prevent or mitigate human rights risks in factories.

Brands should combine such policy and contractual reform with participation in emerging human rights due diligence initiatives. At time of writing, there are three promising initiatives that can aid brands’ human rights due diligence on purchasing practices.

One is Better Buying’s anonymous supplier surveys of brands’ purchasing practices. Better Buying provides industry-wide information while allowing brands to seek tailored reports to help them track their progress using key indicators on purchasing practices. Brands should participate in third-party surveys like Better Buying and publish a summary of the tailored results they receive.

The second are initiatives that seek to combine collective brand action on reforming purchasing practices with sectoral collective bargaining like the Action, Collaboration, and Transformation (ACT) on Living Wages, which is focusing its work in a few key priority countries. Such collective initiatives hold the promise of enhancing brand leverage in shared factories and undercutting supplier competition. Brands should join collective initiatives like ACT. While waiting for initiatives like ACT to successfully conclude sectoral collective bargaining agreements, brands should take measures to at least track, and bolster through business incentives, their suppliers’ respect for workers’ freedom of association and collective bargaining.

The third is a set of labor costing tools developed by the Fair Wear Foundation for all 11 countries they operate in. Brands that do not have sophisticated costing tools that allow them to delineate the labor and social compliance costs at the factory level, should use costing tools like the ones developed by the Fair Wear Foundation.

Finally, brands should regularly publicly report on how their purchasing practices are improving and working to support social and labor compliance in factories using specific indicators. These indicators on sourcing and purchasing practices should be developed along the lines of those suggested in the OECD Due Diligence Guidance on Garments and build on indicators developed by organizations, including the Fair Wear Foundation and the New York University (NYU) Stern Center for Business and Human Rights.

There is a growing movement of conscious consumers and investors who care not just about trends and profits, but also about the workers who make their clothes. Brands should show and explain how they are cleaning up their own house on sourcing and purchasing practices while calling for workers’ rights to be protected in factories.

Methodology

This report is based largely on in-depth Human Rights Watch interviews—sometimes multiple interviews—with 35 garment suppliers, social compliance auditors, and apparel industry experts between April 2018 and January 2019. The apparel industry experts included those with at least a decade of experience overseeing sourcing and purchasing for global brands. The report also draws on previous Human Rights Watch research that entailed interviews with about 500 garment workers in Cambodia, Bangladesh, and Pakistan between 2013 and 2018, and an additional 46 garment worker interviews in Myanmar and India in 2018. It also draws upon a November 2018 workshop hosted by Human Rights Watch with 13 experts who have researched sourcing and purchasing practices, including specialists on labor costing. A review of relevant secondary literature, including export data analysis, also informed this report.

The report does not focus on any one country or brand. It speaks to industry-wide problems that impact labor and social compliance by factories.

When interviewing garment suppliers, Human Rights Watch did not seek any information about specific brands they were supplying or detailed information about product types. This was done in order to satisfy interviewees’ need for anonymity, so they could participate in interviews without putting their business relationships at risk. In some instances, Human Rights Watch has chosen to withhold product details that interviewees provided to further guard against any possibility of reprisals. The suppliers who spoke to Human Rights Watch were mostly producing for international apparel brands.

Unless otherwise noted, events and stories described by suppliers are recent, that is, having occurred between 2016 and 2018. In cases where an example cited predates that range, this is noted in the report.

I. Background: The Perils of Fashion

In early February, the Chinese ushered in the Lunar New Year of the Pig. Peppa Pig, the protagonist of a British animated children’s TV cartoon show, joined the celebrations. She found her way on all kinds of merchandise, including adult t-shirts.[3]

Apparel brands face tremendous commercial pressure to make their product lines responsive to rapidly changing cultural trends, consumer preferences, holidays, and seasonal shifts.[4] The work that goes into making that happen is multifaceted—choosing a sales and marketing strategy, designing a product, projecting consumer demand, setting prices, identifying factories that can manufacture the product, placing orders, and having them lined up and ready to sell before the moment passes.

Speed, increasingly, is key. E-commerce and the use of other technology has transformed the apparel industry, bringing into sharp focus “speed to market.”[5] A 2018 report by McKinsey analyzed the reasons why top global apparel brands are profitable. McKinsey highlighted two key factors about these companies’ operations. First, they used data analytics and consumer feedback early on to develop products and second, they made speed to market a top priority and got “faster and faster.”[6] According to McKinsey, high-performing companies delivered products to consumers within six to eight weeks, compared with the industry average of about 40 weeks.[7]

Brands looking to compete on these terms face many challenges. Among the most daunting is their need to manage their sprawling, complex global supply chains. Global apparel brands typically source from scores of factories they do not own or directly control, in multiple countries, sometimes thousands of miles from their own headquarters or target markets.

Putting that machinery into motion requires a complex and coordinated effort—one that requires planning and forecasting, design and development, sourcing, costing and cost negotiation, the setting of payment terms with suppliers, and the alignment of all this to brands’ commitments on social and labor compliance in supplier factories.[8] Together, this complex set of processes is usually known as “sourcing and purchasing practices” in the apparel industry.

Industry experts believe that going forward, apparel companies should be diversifying their risks by creating nimble supply chains.[9] But the demand to be nimble, fast, and responsive to the consumer also creates pressures that carry serious risks.

As this report describes, brands’ sourcing and purchasing practices often undermine and stand in tension with their stated commitments to ensuring safe and dignified conditions for the workers who produce their wares. The ever-mounting pressure to work faster exacerbates those problems. Instead of holding suppliers accountable for their abuses, these tensions incentivize them and heighten brands’ exposure to serious human rights risks.

For more than a decade, labor advocates and industry experts have pointed to the skewed power relations between brands and suppliers, arguing that brands’ poor sourcing and purchasing practices contribute to negative impacts on labor compliance in their supplier factories.[10]

In global supply chains, international brands usually have more negotiating power than their suppliers.[11] Brands are often in a position to dictate the price they will pay to suppliers, the time within which suppliers should make products, and other purchasing terms.

Brands make these decisions in an environment where not only they are competing, but suppliers too are competing to get brand orders. Unless all brands sourcing from the same factory assume a fair share of their human rights due diligence responsibility, there is not just a risk of free-riders, but also the additional human rights risk to a brand because it has limited leverage to sustainably influence factory working conditions. Brands that do not co-operate with other brands to assume their fair share of responsibility to reform sourcing and purchasing practices, expose themselves to continuing human rights risks instead of acting swiftly to help workers. Where brands simply cut their supplier relationship and quietly exit when labor abuses come to their attention, their sourcing and purchasing practices are not aligned with the principle of responsible exit.

At the supplier level, stiff price competition amongst each other means that suppliers committed to decent working conditions and accurately costing for them carry the risk of brands switching to other “cheaper” suppliers who slash social and labor compliance costs to stay competitive.

Against this backdrop, over the last few years, the momentum to reform brand purchasing practices has been slowly building. Supply chain experts, academics, labor advocates and global unions, the ILO (which runs a factory monitoring program called Better Work), multi-stakeholder initiatives (organizations comprising of brands and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)), and brands themselves have increasingly spotlighted poor sourcing and purchasing practices and called for reform.

At the same time, though, the ever-increasing demands of the global marketplace are putting new pressures on brands that risk reinforcing bad practices and undercutting hard-won progress. In this sense, the industry stands at a real crossroads—one where there is both real momentum towards positive change, and a dangerous current of commercial pressure pushing in exactly the opposite direction.

II. Key Brand Sourcing and Purchasing Practices That Contribute to Labor Abuses

Major apparel brands have adopted codes of conduct and other policies aimed at ensuring their suppliers guarantee safe conditions and rights-respecting terms of employment for the workers who produce their wares.[12] At the same time, though, many brands’ purchasing practices are driven by a relentless focus on speed and cost. The net result of these countervailing practices is that while many brands are demanding better workplace conditions, at the same time they are squeezing suppliers in ways that not only undercut suppliers’ ability to comply but incentivize workplace abuses.

Brand Price Negotiations

“The [number of] compliances [for factories] keep moving up and the prices keep going down.”

―An official from a group that owns apparel factories in several Asian countries supplying international apparel brands, Southeast Asia, May 2018.

The pressure on sourcing teams and buyers is always about finding a better [lower] price [for production at a factory]. There are few times when the question is asked, “Well, if we do this will we have compliant production?” … What isn’t done is the active connection of the risk of pushing in one place [price] and the result comes to bear in another place [factory working conditions]. That’s about business model.

―Industry expert with more than 25 years of experience sourcing apparel, footwear, and non-apparel products for multiple brands, London, January 15, 2019.

In 2016, the ILO published the results of a global survey that it conducted in collaboration with the Ethical Trading Initiatives of Denmark, Norway, and the United Kingdom. The survey results were based on responses of 1,454 suppliers across different sectors and revealed the following:

- 78 percent of apparel suppliers said price remained the “main criterion” brands used when placing orders, while just 47 percent said working conditions were factored into the decision;[13]

- 52 percent of apparel suppliers said prices paid were often lower than production costs;[14] 81 percent said they agreed to such terms to secure future orders.[15]

- According to suppliers, 75 percent of buyers across different sectors (not just apparel) were unwilling to adjust prices when statutory minimum wages were raised. Suppliers said that even among willing buyers, there was on average a 12-week time-lag before they adjusted prices.[16]

The Better Buying Purchasing Practices Index, a new third-party index based on anonymous supplier ratings of brand sourcing and purchasing practices, revealed the following in 2018:

- 60 percent of suppliers said they did not receive any incentives for complying with their buyers’ codes of conduct;[17]

- 55 percent of suppliers reported “high pressure” negotiating strategies;[18]

- Just 38 percent of suppliers said the prices they received were adequate to support compliant production;[19]

- For 27 percent of suppliers, the buyers paid less than the amount finalized in the purchase order;[20]

- Among buyers rated in late 2017, 31 buyers headquartered in Europe and the UK were ranked better for their costing practices than 31 based in North America.[21]

Human Rights Watch spoke with suppliers who echoed these complaints. They also said they had almost no ability to negotiate prices brands paid them because of the stiff competition they faced in the industry.[22]

Suppliers interviewed by Human Rights Watch recounted intense pressure on pricing. One Pakistani supplier who supplies numerous global brands said that the brands “give us a target price and we have to meet it if we want to take the order.”[23] An official from another Pakistani group, with a vertically integrated business with multiple factories, about 70 percent of which supplied to international apparel brands, said he did not even think price discussions could be called “negotiations.” “There is no price negotiation. There are just too many options [other suppliers] for them…. It’s like buying eggs for them [brands].”[24] An Indian supplier described the pressure to reduce costs and contrasted them with brand demands regarding quality and compliance. He said: “There is a difference between the price of a bus ticket and a flight ticket. You can’t pay for a bus ticket and expect to feel like you are flying.”[25]

One Supplier’s PerspectiveAn official from a supplier group who oversees the group’s business and operations across its factories in several Asian countries, explained how international apparel brands he did business with had consistently sought to drive prices down over the last five years. Drawing upon his experience of negotiating business with 17-20 brands over several years, he said that “even with the same orders, repeat orders, even with smaller quantities, the prices go down—5 percent sometimes; maybe 2-5 percent. Even the same order, everything is same—this is a big issue for us.”[26] He noted that over the same period, statutory minimum wages had risen in several countries where the group owns factories. He said brands tried to negotiate the price down by pressuring them to reduce cut-and-make costs, which is the part that includes workers’ wage bills. “Labor costs are under the CM price [cut and make price]. It’s not separated out. But if they think the price is too high, it’s always the CM—they want us to cut our CM price. It always happens.” He said that some buyers are themselves reluctant to take account of suppliers’ cost breakdowns because they laid bare realities that they would prefer to remain ignorant of: I have some friends who are big buyers for American brands and they know they will never get the target price if they use open costing [transparent costing]. They say for example $10 [per piece]. If you make an open calculation sheet and use time measurements for work—you need $12—you cannot get $10. They start with open calculation and then suddenly say, “We don’t want to see it [the costing sheet].” In another example, where the same official was doing business with a global brand that was keen to pay workers a “living wage,” he said, “I made a living wage calculation and showed one of our biggest customers [brands] how he should change the price for me to pay the living wage. They said it was unrealistic.” |

Not Factoring in Statutory Minimum Wages

A key concern that suppliers raised was that many brands do not factor increases to existing statutory minimum wages into their prices. One supplier from Pakistan who estimated that about 95 percent of their production is for US brands said that brand prices were not adjusted to accommodate the government’s increase of statutory minimum wages. Reflecting on his experience of doing business with long-term buyers, he said, “The impact on my payroll because of wages and social security [contributions] was 10-15 million [Pakistani rupees, roughly $70,609 to $105,913].”[27] Another large Pakistani supplier who manufactured for 12-15 American and European brands, said that some brands expected to be able to pay the same prices even when wages went up:

The problem arises when you have a similar or a repeat order. For instance, if … they place the same order each time, there we have to have this conversation. The Europeans are friendlier to these changes. The Americans, they say, “as good as your last shipment.”[28]

Shelly Gottschamer, an expert with more than two decades of sourcing experience, said that brands should pay suppliers prices that weave in statutory minimum wages. She said most brands should be negotiating seasonal costs at least a few times a year and “if there are labor increases that are either happening [at that time] or imminent, then there should be a conversation and a discussion about an increase in the minute rate that you are paying your suppliers.”[29] She further stated that fair increases to reflect impending minimum wage increases should be made by brands,

[U]nless a brand has its head in the sand, which comes down to the management practices and that really starts at the top. If you are a brand that says you care about social and labor conditions, most likely you are paying attention to the labor markets where you are doing business. Some brands just don’t and that’s really the problem.[30]

One former sourcing expert said that a brand’s leadership should change how business decisions are made by enabling buying teams to adjust prices to reflect legal minimum wages:

It’s entirely up to the leadership of the company. It is about enabling by the leaders and being thoughtfully connected to the implications of the business. Does anyone actually tell the CEOs, “By the way, boss, we buy 20 percent of our season from Bangladesh and the government has put its wage rates up. Strictly speaking we should be paying an extra $100,000 for our garments from Bangladesh for this season. But we are not going to, and that just probably means there are a bunch of workers in our supply chain who are not being paid minimum wage.[31]

Buying Agents

Some global apparel brands use buying agents to source their products—essentially, middlemen who identify and negotiate with suppliers on a brand’s behalf. Buying agents can play an important role for brands that do not have sourcing teams with the necessary language and geographical expertise to locate appropriate suppliers. Some buying agents may also provide additional services, such as warehousing, which allow suppliers to save costs.[32] But brands risk having little visibility over buying agents’ own business practices or those of the suppliers they work with unless they take specific measures to ensure transparency. For this reason, many industry experts say that global apparel brands’ use of buying agents presents a higher risk for poor sourcing and purchasing practices and workplace abuses.[33] Some experts have argued that brands should move away from any use of buying agents, as the only practical way to address those problems. Where brands use buying agents, they should demonstrate that they have a robust human rights due diligence mechanism specifically designed to address the additional risks presented by their use of buying agents, including any commissions and bribes that unscrupulous agents may charge factories, effectively reducing the total money the factory receives.

A former sourcing and compliance expert who worked for a North American retailer for over 10 years spoke about the challenges of using buying agents. When she began working for the company, she said that the company used the services of about 300 buying agents. They had very little visibility over their supply chain and estimated the agents used about 1,000 factories and potentially as many as 2,000 factories. “[The agents] had their network that was extensive and constantly changing. We were negotiating pricing without any visibility,” she said. She began a process of reducing the use of agents, cutting down from 300 to a handful of agents.[34]

When asked whether the brand had any information about the final price that was paid to the factory for production, she said that she had no information about this.

That’s the biggest challenge—we had no idea about the end price paid to the factories. When we started working directly with factories, that’s when we realized how much the agent was making. It’s more important to push for transparent costing with agents.[35]

Even though she did not have visibility over the actual price paid to factories producing for them via buying agents, she said that she did have some visibility over compliance in these factories because she was involved in social audits.[36] “The difference was night and day,” she said describing the labor conditions in factories that produced for the brand via a buying agent and factories that directly did business with the brand. “Through agents, that’s often when we find out they are producing on a rooftop, illegally, or there’s trash a meter-high blocking pathways. These factories also have transactional (casual) workers who come and go every day and they are paid cash.”[37]

Another expert with 20 years of experience sourcing for multiple multinational brands said that when she worked with buying agents, “ultimately knowing the supplier was very difficult.”[38] She explained further:

You lose control of not just compliance, you also lose control over visibility and pricing. If you get into a costing dialogue with the agent asking for [price] reduction, they can change the supply chain without telling you, to get the lowest price. And we won’t know about compliance and other things in those factories.… That’s why I tried to buy direct as much as possible.[39]

In addition to buying agents trying to maximize their profits by driving down prices, she also said that there were “hidden costs between agent and the supplier,” referring to kickbacks that unscrupulous agents can demand. “That’s common knowledge. There is no way to catch it. It is under the table and it is a dirty little secret. These hidden costs also present conflict of interest issues for agents. The agent is supposed to represent the brand. So, if he’s taking kickbacks from the supplier, then who is he really representing?” she said.[40]

Another industry expert who has worked closely with factories in Bangladesh and other parts of Asia, as well as South America, reflected on his experience of looking at labor conditions in factories:

Working conditions in factories chosen by buying agents are worse. I’ve been doing this for 30 years now. [I] noticed that brands are getting away from buying agents big time…. You don’t go to an agent unless you have no clue about the market. The thing about labor agents for brands is that they do get them a cheaper price—they have a much stronger portfolio of factories. An agent who knows many different buyers will keep the factory busy all the time. [But] there’s a double payment. The labor agent takes a cut from the price and the working conditions are worse.[41]

An Indian supplier who worked with a brand’s buying agents described the “commissions” he had to pay: “One of the agents sets a flat 10 rupees ($0.14) per piece. It doesn’t matter whether the entire garment costs 50 rupees ($0.72) or 500 rupees ($7.20).”[42]

Shortened Lead Times, Penalty Clauses, and Payment Delays

Lead times promised by factories play a critical role in determining whether brands place orders with them.[43] Lead time is usually understood as the time from the date an order is confirmed to the date the products are readied for shipment at the factory.[44] As is true with prices, suppliers complain that a combination of factors—shrinking lead times, a lack of brand awareness about when precisely bulk production can start, and unfair penalties for missing production deadlines—create severe pressures that are incompatible with brands’ professed commitment to rights-respecting workplaces.

Shortening Lead Times

Overall, lead times are dramatically shrinking.[45] The 2019 McKinsey State of the Fashion Report revealed how “speed in production is critical to every fashion label and retailer—not just the purveyors of fast fashion” and that “reduced lead times will be key drivers of competitive advantage.”[46] While a range of measures are being taken by companies to cut lead times including moving towards automation and near-shoring (shifting production to locations that are geographically closer to the markets),[47] suppliers and sourcing experts said that the speed-to-market pressure is passed on to factories, which in turn impacts workers.[48]

The 2016 ILO supplier survey revealed that only 17 percent of respondents across different sectors (not just apparel) believed they had sufficient lead time to produce goods.[49] The survey also revealed that 59 percent of suppliers across different sectors said that short lead times did not allow them to plan production effectively, leading to additional overtime.[50] Respondents said that shorter lead times resulted in suppliers’ increased use of overtime work, subcontracting, or hiring casual labor to meet deadlines.[51]

One supplier told Human Rights Watch: “We are getting pushed more and more to reduce our lead times…. If we don’t agree to the lead times, we might lose the order.”[52] A supplier from Pakistan also said that buyers were reducing lead times. On some products for which lead time was more than 60 days about five years ago, he said brands now expected them to be produced within a month.[53]

A former compliance expert who worked for a leading European brand for a decade and across multiple countries, said:

These are competitive enterprises—the factories—so sometimes the factories will take on more production that can be done during reasonable working hours. So, if the brand actually cares about those things then it’s up to the brand to push back and ask the right questions. And there’s definitely a big spread on the level to which brands take ownership of these issues, engage with the factories and have knowledge.[54]

Use of buying agents can also squeeze the actual time available for bulk production, putting pressure on factories, and in turn, workers. For example, a former sourcing and compliance expert said that the brand had mapped out the time it needs from design to finalizing the purchase order. But eventually they realized that the buying agent was taking another three weeks to transmit the purchase order to the factories and place orders.[55]

Brand Delays and Poor Forecasting

Brands that delay a factory’s ability to start bulk production without readjusting delivery dates put additional pressure on the factory. Moreover, brands that suddenly modify orders without addressing how the factory’s production capacity and workers will be impacted, also contribute to poor working conditions in factories.[56]

The Better Buying Purchasing Practices Spring Index 2018 found that brand-driven delays were a significant problem. According to suppliers, only about 16 percent of buyers met all agreed-upon deadlines in the product development and pre-production stages; another 20 percent of buyers failed to meet these deadlines about 80 percent of the time.[57] Most delays were caused in the pre-production stage.[58]

One Indian supplier, who until recently supplied international brands through a buying agent as well as indirectly through subcontracted work (“job work”) for exporters, said, “Buyers do badmashi (play dirty),” when it comes to lead times. He explained how some buyers had set a delivery deadline for about 60 days from the date of the order, but subsequently took as long as one and half months for all approvals. “It leaves me with 15 days to produce. And when I can’t meet the deadline, they start to say ‘late delivery’ and demand discounts.”[59]

Another supplier described how a brand wanted products manufactured within two weeks, but without providing complete details regarding size on time, delaying production. “It later led to air freight for me. But this was very stressful, and I had to fight a lot. Sometimes they push for delivery within two weeks—big huge misunderstanding regarding how it [production] really works.”[60] A common problem he experienced from some brands was the prevalence of delays in approving fabric and samples but without extending the time available for workers to produce:

Fabric and color swatches [are sent] to the customer and approval takes time. In our business we have lots of designer jokes, “The black is not black enough.” One Italian customer never confirms color. You send them six times, eight times—they just don’t confirm. And then finally when you tell them, “Your delivery will be delayed one month,” they say “No, no, it cannot be delayed. We confirm the second one.” We don’t understand this.[61]

Brand Penalties and Costs for Suppliers Missing Deadlines

Short lead times and hard delivery deadlines are often backed by the threat of penalty clauses. The 2016 ILO survey of suppliers found that 35 percent in the textile and clothing industry said they faced penalties from buyers for not meeting deadlines.[62] Based on supplier survey data, the Better Buying Purchasing Practices Index Spring 2018 found that about 9 percent of the buyers were said to be inflexible about deadlines and prices even when they were responsible for delays.[63]

During in-depth interviews, suppliers told Human Rights Watch that many brands demanded discounts on the invoiced price, unreasonably citing “production delays” or “defects.” Another cost that suppliers said they often solely bear was air freight if they missed the shipment date. Suppliers also drew Human Rights Watch’s attention to brands’ practice of unreasonably canceling orders altogether in reaction to even the slightest of delays.[64]

For example, one Indian supplier, who has produced for foreign buyers, reflected on his experience of doing business with them. According to him, one category of foreign buyers “has good payment terms and don’t try to cheat you. They won’t demand discounts using small excuses or don’t stop or delay your payment.”[65] But these buyers cited their promptness in clearing payments as leverage to demand lower prices. A second category of foreign buyers he described as “the kind that doesn’t intend to pay at all.” He explained that these buyers demanded massive discounts on the invoice citing small excuses. “When they don’t intend to pay you at all, it’s easier for them to offer better rates per piece. The best buyers have given me an advance of 40 percent of the payment before production starts and then the remaining when I finish the goods,” he said.[66]

|

Terms and Conditions in Contracts

Detailed, written manufacturing contracts are not common in the industry, though there is some momentum in that direction.[67] One Indian supplier said that detailed manufacturing contracts are typically developed only when a big company sources 100 percent from one factory for multiple years and considers it a significant investment.[68] Where brands do not have a detailed manufacturing contracts, the purchase orders carry terms and conditions to varying degrees.[69] Where purchase orders are silent about delivery delays and penalties, these are usually discussed before the orders are placed.[70] Irrespective of whether there are written terms or conditions, sourcing experts and suppliers Human Rights Watch interviewed said that whether brands charged penalties was ultimately left to the complete discretion of the brand.[71] For example, one manufacturing contract said: Delays and Penalties: TIME IS OF ESSENCE IN ANY PURCHASE ORDER. Shipments must be on-board Company’s carrier (in the case of FOB purchases) or Manufacturer’s carrier (in the case of DDP purchases) on next vessel close date after the ex-factory date specified in the Purchase Order and, in no event, more than seven days following the ex-factory date (the “On-Board Delivery Date”). If for any reason Manufacturer does not comply with Company’s On-Board Delivery Date, Company may at its option either approve a revised delivery schedule, require air freight shipment at Manufacturer’s expense, or cancel a Purchase Order without liability on the part of Company to Manufacturer.[72] Suppliers alleged that in some cases, brands misused these penalty clauses to pass on losses they faced if their products did not sell in the market.[73] A London-based sourcing expert said that brands’ fair exercise of discretion to waive or invoke penalty clauses depended on brand leadership and messages that different departments received. She said that she was aware of brands that used penalty clauses to meet their profit margin goals. Another industry expert with nearly three decades experience sourcing for a multinational corporation that owns numerous brands said that penalties were decided on a case by case basis. He explained that financial penalties were an area where brands showed “who has the bigger baseball bat.” He said he was aware of brand practices where brands cut 1 or 2 percent of the freight on board (FOB) costs from the supplier if the brand sales were bad.[74] He explained that suppliers did not have a choice but had to agree because “they won’t get business anymore.”[75] |

For suppliers, it is far more expensive to ship finished goods by air. Design or other last-minute changes to an order often put factories in the position of having to choose between incurring steep air freight costs to meet agreed-upon delivery times—or finding ways to make their workers finish the order more quickly.[76] Because flights are prohibitively expensive compared to shipping finished products, one factory official explained how he stood to lose money on the order if he missed the shipping deadline. “It’s cheaper for me to get workers to do overtime work and try and meet the delivery date for shipment than be delayed and pay for flight costs.”[77] One supplier in Pakistan said:

Workers might have to do OT [overtime] because of orders. It could be that we accept orders with delivery dates but not have all the approvals for style, sample, etc. And in that process, our delivery date gets squeezed. Then we have to do what we can to meet the delivery date. Some companies [factories] are smarter and calculate what costs more—OT or air fare.[78]

Delayed Payments

Unfair payment terms and delayed payments compound cash flow problems for suppliers. Extended payment windows require factories to take loans from banks to have money for operating costs, and interest rates vary from one production country to another. While brands’ payment terms vary widely, one industry expert said that most large brands and retailers that he had come across stipulated 90 or more days from the date of shipment, to pay the supplier.[79] Longer payment windows pose an unfair burden on suppliers, unless brands offset such delays through other favourable commercial terms for the supplier.[80]

According to the Better Buying Purchasing Practices data in fall 2018, about 65 percent of buyers adhered to payment terms and cleared bulk invoices on time.[81] Where they were delays, buyers took anywhere between 21 to 100 extra days from the actual agreed upon date, to make payments.[82]

United Kingdom Prompt Payment CodeThe Prompt Payment Code in the UK is a set of voluntary standards and payment best practices for UK businesses.[83] The Chartered Institute of Credit Management implements the code on behalf of the UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. Code signatories undertake three key commitments—to pay suppliers on time, give clear guidance to suppliers regarding payments, and encourage good practice where lead suppliers should encourage that the code is adopted throughout their supply chains. Code signatories undertake to make payments within 60 days and endeavour to pay within 30 days. As of early April 2019, the code had 2,258 signatories.[84] |

III. Human Rights Abuses Fueled by Brand Purchasing Practices

Brand purchasing practices can be much more than just a headache for suppliers and a threat to their financial bottom line. Because they drive suppliers to work unreasonably fast while at the same time slashing costs, bad purchasing practices can incentivize abusive labor practices and risky contracting with unauthorized suppliers whose own labor practices may be abhorrent. This means that brand practices in these areas directly undercut their own efforts to insist on rights-respecting working conditions across their supply chains.

This report’s emphasis on the need for better human rights due diligence of brands sourcing and purchasing practices does not lessen the responsibility of supplier factories, especially to respect workers’ right to organize freely, prevent workplace abuses, or hold accountable staff who sexually harass or resort to verbal and physical abuse of garment workers. The reality, however, is that suppliers respond to the incentives brands create for them—so it is vital that brands are driving supplier practice in a more rights-respecting direction, rather than incentivizing abusive practices that might lower production costs.

Wages and Hiring Practices

Violations of laws governing minimum wages, overtime pay, and other aspects of compensation are a persistent industry challenge.[85] Problems are clearly widespread. The ILO’s Better Work program found in a 2013 study (the latest available aggregate study) surveying five countries—Vietnam, Indonesia, Lesotho, Jordan, and Haiti—that all of them experienced widespread wage-related violations.[86]

Union leaders have protections under national laws and have the right to collectively bargain on behalf of workers with the factory management to improve wages and other working conditions. Where unions are independent and chosen freely by workers themselves, they can take steps to hold factories accountable labor abuses, including timely and accurate payment of wages and benefits, by assisting workers raise individual or collective disputes. Factories across different countries often do not allow workers to freely form or join unions.[87]

Good collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) at the factory level carry negotiated wages and benefits that are better than those set out in national labor laws. For example, in a 2015 CBA negotiated by an independent union with a factory in Cambodia, the workers negotiated a wage increase and basic wages higher than the government notified minimum wage. Workers also negotiated other paid worker benefits and breaks. The agreement also sets out dispute resolution procedures.[88] In a 2019 CBA negotiated by an independent union with a factory in Bangladesh, the workers and factory management agreed to a 10 percent annual increase in workers’ wages; a minimum number of annual promotions for women workers (which would increase their salary slab), other paid benefits, and a dispute resolution mechanism.[89] Brands that support workers’ freedom of association and collective bargaining but seek to drive down prices without factoring in labor and social compliance costs aligned with CBAs, fail to pursue a pricing strategy that prevents and mitigates human rights risks.

Overtime-related violations have been an intractable industry problem, and double bookkeeping to hide overtime hours is widespread. The ILO’s 2013 synthesis report stated that “a cross-cutting issue across all countries … is the presence of double books and inaccurate payroll records…. This is a widespread practice in the garment sector as suppliers are faced with pressures by buyers to produce quickly and at a low cost.”[90]

Factories deploy myriad ways of avoiding overtime pay that may be difficult for brands to detect absent very robust compliance mechanisms. For example, in mid-2018, a group of workers in Myanmar described how their factories had “stolen minutes” from them. They elaborated that their managers had set “hourly” production targets for every 45 or 5o minutes.[91] A labor rights advocate who routinely interacts with workers from scores of factories in Myanmar said that it was a common practice by factories, which sought to intensify work to avoid paying overtime wages.[92]

Similarly, in India, workers from a factory described how they did overtime work during weekdays and on Sundays without overtime pay. The factory management told them they would adjust what was due as overtime pay as “earned leave,” subsequently forcing workers to take paid time off for 3-5 days during low season when the factory did not have sufficient business.[93] One of the workers said, “I did a lot of OT [overtime] dreaming of the extra money I would get and what I could do with that money. I was in tears when they said they wouldn’t give us any money for OT and [that] we would be given paid leave instead.”[94]

Industry sourcing or compliance experts drew upon their experience, narrating how they had seen brand sourcing and purchasing practices helping to fuel such problems.[95] One sourcing expert with more than 30 years’ industry experience explained that excessive overtime or unauthorized subcontracting were driven by brands that did not forecast at all or forecasted poorly.[96] He reiterated the importance of brands monitoring the difference between their projected and actual orders placed with factories. He said, “If a brand says [to a factory] they are going to order 150,000 pieces and then at the time of actually placing the order, turn around and ask for 250,000 pieces, then you are going to have OT [overtime] or subcontracting.” In 2018, while advising suppliers, he said he had found huge variations between brand projections versus actual orders, estimating that they were off about 80 percent of the time, causing problems for factories and their workers.[97]

Shelly Gottschamer, a sourcing and compliance industry expert, reiterated the importance of brands paying attention, not just to excessive working hours during bulk production, but also when samples are being made. Speaking from her previous experience, she said that where brands added another style to the collection last minute and shortened the time for the samples to be produced, it resulted in excessive work hours for those making the samples.[98]

A former social and labor compliance expert who had worked extensively in China and Southeast Asia recalled an egregious case he witnessed in 2009 in China. While this case is dated, he explained that this stood out for him because of the extreme and direct consequences a brand’s sourcing and purchasing practices had on the factory’s workers. He and his colleague visited a Chinese factory to conduct a social audit. The factory was one he was familiar with from several previous visits in an auditing capacity. He described that the day he visited the factory they “noticed that something was very wrong. There were many more people. There was a very bad atmosphere in the workshops.”[99]

After speaking to the factory management, they learned that they had taken on a huge order for a North American buyer, putting all other buyers on hold for a period of six months or so, expecting to make a big profit. But the factory received poor quality fabric and was forced to send the fabric back to the dyeing mill. The factory approached the North American buyer explaining what had happened, seeking additional time to complete production, which was refused. He said, “[T]he direct consequences of that were that everyone had to work a lot more—more than 300 hours a month,” which resulted in excessive overtime for workers.

The second consequence was massive recruitment of temporary workers. He described how the factory “went on this recruiting spree in the northwest of China” and estimated that of about 90 people recruited from really poor areas of the Chinese country side, 25 were children. “This is a horrible example and is quite extreme…. But what it shows is that purchasing practices do affect working conditions,” he said.[100]

Pakistan Case Study: Factories Use Poor Worker Hiring Practices to Cut Costs

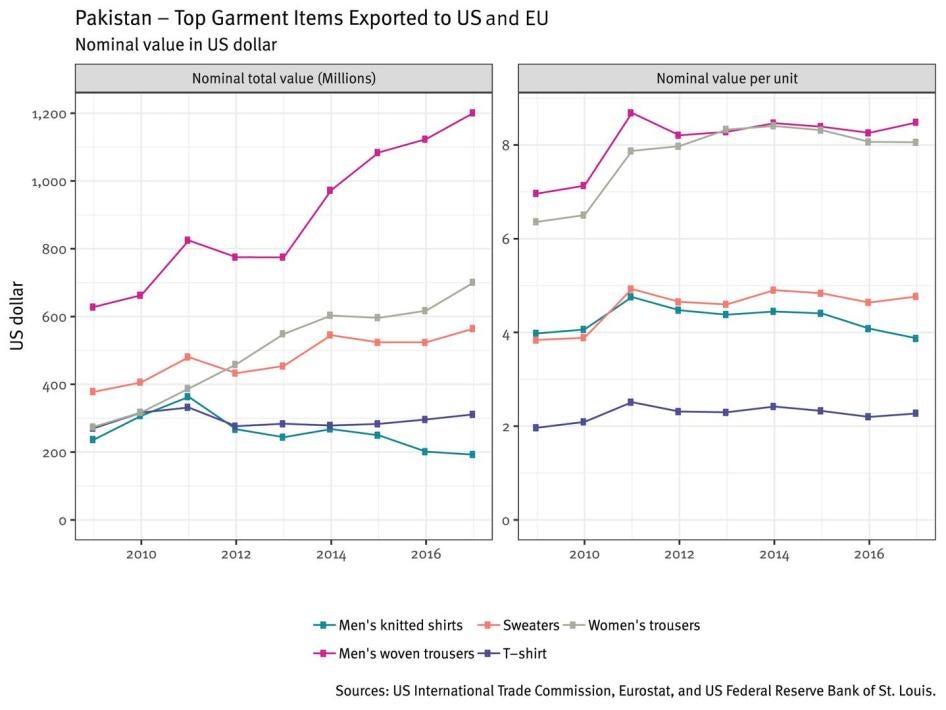

Human Rights Watch analysis of data of apparel exports from Pakistan to the EU and the US between 2011 and 2017 shows that for the top five product categories, the nominal US dollar price per garment was largely stagnant, even though the Pakistan government consistently raised the minimum wages.

|

Year |

Monthly Minimum Wages in Pakistan (in Pakistani Rupees) |

|

2008 |

6000 (US$43) |

|

2010 |

7000 ($50.5) 8000 ($57.7) in Punjab |

|

2012 |

8000 ($57.7) 9000 ($65) in Punjab |

|

2013 |

10,000 ($72) |

|

2014 |

12,000 ($ 86.6) |

|

2015 |

13,000 ($93.9) |

|

2016 |

14,000 ($101) |

|

2017 |

15,000 ($108) |

|

Source: Clean Clothes Campaign and Labour Education Foundation, nongovernmental organizations. |

Six Pakistani suppliers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that there were no meaningful price negotiations between them and the brands they worked with. Against this backdrop of intense price pressures, a range of workplace abuses are tied to suppliers’ desire to cut costs. One official with over seven years’ experience working for two apparel factories (different from the suppliers we spoke with) producing for global apparel brands described measures factories take to cut costs. He said that hiring workers through contractors and showing fewer workers as “permanent” on the payroll allowed factories to minimize costs, in large part because it obviated the need to pay the statutory benefits an employer would have to pay a regular worker:

A lot of factories hire workers through contractors. Let’s say I am a supplier or an owner. I have a factory and have to produce 200,000 jackets every month. I will talk to a few thekedars (contractors) and they will come to me and the rates are set. I will set a lump sum amount for the job. The factories don’t want any headaches [paying wages and benefits]. They will hand over the amount to the contractor and the contractor will distribute the salary to workers. These workers will not get any benefits because the contractors will not pay any benefits.[101]

Second, factories also paid lower social security contributions than they should: “A factory that has 1,000 workers pays pension and social security contributions for about 50 to 100 workers.”[102] He said it was easy to generate fake vouchers showing that contributions were paid for everyone and it was a well-oiled system of keeping costs low because government’s regulatory mechanisms are weak.[103]

When asked about poor social security contributions, one Pakistani supplier said, “There are people [factories] who don’t pay EOB [Employees’ Old-Age Benefits], it’s a cost-cutting method. They do it because their costs are too high and when they factor it all in they are unable to compete.”[104]

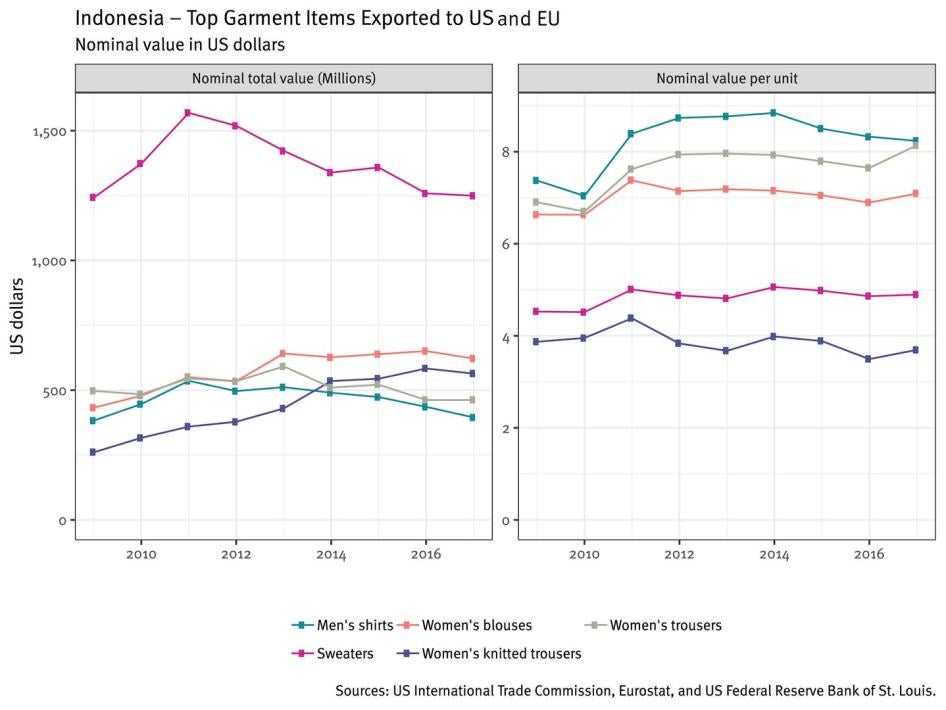

Spotlight on IndonesiaHuman Rights Watch analysis of EU and US trade data for apparel exported from Indonesia shows that since 2011 the nominal price per garment for the top five products (by value) produced in Indonesia has largely remained stagnant. The ILO’s Better Work program reported in 2018 that 35 percent of the factories it monitored did not comply with minimum wage rules;[105] 76 percent of the factories did not pay social security and pension contributions as required under the law.[106] Excessive overtime is a huge problem in Indonesia—66 percent of surveyed factories violated daily and weekly overtime limits, and about 49 percent of factories did not make accurate overtime wage payments.[107] An auditor from Indonesia, who has more than a decade’s experience conducting social compliance audits, felt unfair purchase prices contributed to factories trying to cut costs by resorting to abusive labor practices. Despite significant minimum wage differences amongst provinces, he learned while conducting social audits that the prices brands paid did not reflect these minimum wage differences, leading factories to take cost-cutting measures that impacted workers: In Indonesia, every district has a different minimum wage. Jakarta has about 3.5 million rupiah ($247) for a month. In other provinces like West Java, the minimum wages—the lowest minimum [wage] is 1.5 million rupiah ($106). But the price for the garment is the same whether brands produce in factories in West Java or East Java. How can this be?[108] |

Work Intensification

Shorter lead times combined with low buying prices drive factories to reduce costs, especially in the context of increasing minimum wages. This can result in work intensification, where factory managers revise workers’ hourly production targets upwards.[109]

Over the years, there has been a common thread running through most of the interviews Human Rights Watch carried out with garment workers in Cambodia,[110] Bangladesh,[111] India,[112] Myanmar,[113] and Pakistan[114]: relentless, ever-mounting pressure to work nonstop. Some common methods of getting workers to produce more include restricting workers’ toilet breaks; trimming their meal breaks; squeezing “trainings” into lunch or other rest breaks so the “production time” is not lost; and disallowing drinking water breaks and other rest breaks.

Nay San Lin, a 19-year-old male worker, said that his factory in Myanmar suddenly increased the hourly production targets over the course of one month in mid-2018, from 100 pieces to 120 pieces, and then 200 pieces.[115] Myanmar had increased its minimum wage earlier that year. Similarly, workers in Cambodia complained that factories had increased their targets after the minimum wages were raised, mounting intense pressure on them to meet these targets and undermining their ability to take breaks.[116]

Panh Ei Cho, a garment worker from Myanmar, recalled being publicly humiliated in her factory in early 2018. As she was using the factory’s toilet, she heard her name reverberating through the public announcement system. Her line supervisor was unhappy with her “frequent” toilet breaks and decided some public shaming was in order. The factory management’s expectation was that Panh Ei Cho should be sewing, oblivious to her bodily needs. She had diarrhea that day.[117]

Fawzia Khan, a 24-year-old unmarried woman worker who was working for over a year in the sewing department of a Pakistani factory producing for international brands said:

I hate the jail-like atmosphere at the workplace, the ban on going to the bathroom, the ban on getting up to drink water, the ban on getting up at all during work hours.... And the one hour that we are supposed to get off during the day is actually only half an hour in practice. I don’t remember the last time I got a full one hour break.[118]

A Gender Lens: The Differential Impact of Work Intensification on Women Workers

The pressure to work faster and without breaks takes a different toll on women workers. The majority of workers in the apparel industry are women of reproductive age.

Sexual Harassment and Verbal Abuse

Women workers have recounted examples of male line supervisors asking for sexual favors in exchange for lighter workloads or approving leave.[119] Alternatively, they have described putting up with sexual harassment at the hands of male mechanics, who they depend on for properly maintained machines to be able to work fast.[120]

Workers from different countries have described enduring verbal abuse, including sexualized humiliation of women workers, at the hands of line supervisors or managers, especially to goad them into working faster.[121] That underlying pressure is only increased when suppliers respond to brand purchasing practices by trying to push production forward at an unreasonable pace.

In many cases, workers themselves work without taking breaks, explaining that they do so to avoid having verbal abuses being hurled at them by line or floor supervisors.[122] Kanthi K., a 48-year-old married worker in an Indian factory producing for international brands described how the floor in-charge supervisor pressured workers to do more work by humiliating them: “You’ve done only so many pieces? And why have you passed this [for quality check]—don’t you see it needs alteration? You’re as old as a donkey. Why do you come to work? Go die somewhere else.”[123]

Jina Reza, a 34-year-old married worker from a Pakistani factory producing for an international brand described that the supervisors—all men—hurled verbal abuses at the workers to make them work faster, and that the abuses increased in the months of November and December, which she said were peak production seasons.[124]

In 2014, an ILO Better Work discussion paper drawing upon survey data on verbal abuse by supervisors in garment factories in Vietnam, Indonesia, and Jordan, found that factories were more likely to foster an abusive environment for workers when wages were low, supervisors’ pay was tied to productivity, or factories had too many “rush orders.”[125]

The Toll on Women’s Reproductive and Sexual Health, Pregnant Workers

Menstrual cycles—a natural part of all women’s reproductive health—increases women’s needs for toilet and other breaks.[126]

Menstrual hygiene challenges at the workplace are multiple. These include managers not understanding women’s need for additional time in the toilet to manage menstruation; managers not being familiar with how women may use “checking” to prevent staining their clothes; difficulty raising menstrual hygiene issues with male staff; a lack of facilities for disposing of sanitary pads or menstrual cloths; and a lack of facilities to provide workers with sanitation products.[127]

Anecdotal evidence through group discussions with women workers in Myanmar and India revealed that women are seldom able to raise concerns about the need for more frequent toilet breaks or small breaks to relieve them of menstrual cramps. This is partly due to cultural taboos or diffidence. But even where workers used euphemisms about “hip pain” and “that time of the month” to try and get their line supervisor to allow them a break, or where there were female line supervisors, they said that they were not successful. They recounted instances of being humiliated for “disrupting” the production line when they ask around for sanitary products, or demand clean facilities, or ask permission to use the toilet frequently when they are menstruating.[128] A few also reported being asked inappropriate questions about their sex lives.[129]

Pregnant workers, in particular, often become casualties in this increasing pressure to work faster. Many factories often perceive them as “unproductive” because of their needs for more breaks and rest and either fire them or do not renew their contracts.[130]

Unauthorized Subcontracting to Abusive Factories

Outsourcing production to smaller, low-cost units without brand permission is another method used by factories to cut production costs or meet production deadlines.[131] Typically, brands forbid unauthorized subcontracting—in part because it leaves them in the dark about the conditions facing workers who produce their goods.[132] But brands often struggle to detect these unauthorized arrangements, and their own sourcing and purchasing practices often create the pressures that lead suppliers to turn to them.

Sourcing or compliance experts identified poor forecasting, brands’ lack of monitoring factory’s capacities, the use of buying agents, absence of ordering time tables, last minute design changes, and low prices as among the brand purchasing practices that contribute to the use of unauthorized subcontractors by factories.[133] One sourcing expert estimated that in the mid-1990s, it took about a year for a company to produce clothes that reflected the style or design of an outfit worn by a celebrity. But “[n]ow, Kim Kardashian wears something and I expect to be able to go online and buy it within four or five weeks.”[134] She described how sourcing managers typically work:

We’ve got this style, we’ve designed it, and got all the raw materials in order. And I need 10,000 units made and I need them in stores in a month. There just aren’t factories sitting around waiting for me to rock up with 10,000 units—where they have nothing to do and they just happened to be free and available and they have all the right quality, skill set—it just doesn’t happen. So what happens as a sourcing or buying person you go to a factory that you know well and you know they can execute this thing [order] and say, “Is there any way you can execute this quantity in this time frame?” And guess what? They [the factory] will always say yes. How are they doing that? They are going out and finding someone in their network who can do it—and that’s unauthorized subcontracting.[135]

Cambodia Case Study: Growing Subcontracted Factories

Human Rights Watch has documented growing unauthorized subcontracting in Cambodia since 2012. The subcontractor factories Human Rights Watch saw in 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2016 were mostly operating out of large sheds or what looked like rural homes. Between 2014 and 2016, the number of subcontractor factories producing mostly for the export market nearly trebled—from 82 to 244.[136]

Even though the government raised the monthly basic wage (that is without adding mandatory allowances) from $100 to $153 between 2014 and 2017, EU and US trade data shows that nominal apparel prices per unit paid by international apparel brands for top five products (by value) manufactured in Cambodia mostly dropped during the same period.

In 2016, Human Rights Watch physically mapped 45 subcontractor factories in Kandal province with the help of workers. This was in addition to a few other subcontractor factories Human Rights Watch discovered in Phnom Penh. Most of these factories were unmarked, making it difficult to even detect that the building housed a factory.

|

Year |

Monthly Minimum Wages in Cambodia (in US$) |

|

2008 |

56 |

|

2010 |

61 |

|

January 2012 |

61 (the government supplemented this basic wage with a mandatory health care allowance of $5) |

|

September 2012 |

61 (the government supplemented this basic wage with mandatory allowances—$5 for health and $7 for transport and accommodation) |

|

May 2013 |

80* |

|

February 2014 |

100* |

|

2015 |

128* |

|

2016 |

140* |

|

2017 |

153* |

|

2018 |

170* |

|

2019 |

182* |

|

Source: ILO, “How is Cambodia’s Minimum Wage Adjusted,” Cambodian Garment and Footwear Sector Bulletin, Issue 3, March 2016, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_463849.pdf (accessed April 8, 2019); Worker Rights Consortium and Clean Clothes Campaign. *All the rates indicated are basic wages. These are supplemented by mandatory transport and accommodation allowance of $7. |

In three factories where Human Rights Watch interviewed workers from export-oriented factories in Phnom Penh, the workers said that the managers from their factories had organized transport and encouraged workers to go to the subcontractor factories in Kandal and work after a full day’s work in the main factory, or alternatively on Sundays. This allowed these factories to employ their workers at another site without paying them overtime wages, special rates for night work or Sunday work, while violating weekly rest day standards for workers.[137]

Human Rights Watch found that workers in subcontractor factories had worse working conditions compared to larger factories producing directly for global brands. Workers working in subcontractor factories whom we interviewed said they did not have health clinics and they did not receive paid sick leave or other paid benefits even though workers were legally entitled to these benefits.[138] Workers also found it more difficult to form unions in subcontractor factories.[139]

Poor Occupational Health and Safety

The primary responsibility to create and maintain safe working premises rests with factory owners. But it is important to recognize that brands’ sourcing and purchasing practices are critical in the context of occupational health and safety because of the significant financial investments that are often needed to improve factory conditions. While some big suppliers, who are conglomerates, have the resources to make such investments, other smaller suppliers’ ability to carry out remediation is more influenced by brand purchasing practices.

Case Study: Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh