Summary

Jewelry and watches denote wealth and status, as well as artistry, beauty, and love. Gold and diamond jewelry in particular are frequently purchased as gifts for loved ones and for special occasions. Globally, about 90 million carats of rough diamonds and 1,600 tons of gold are mined for jewelry every year, generating over US$300 billion in revenue.

The purchase of bridal jewelry, including engagement and wedding rings, has particular emotional and financial significance. In India, for example, weddings generate approximately 50 percent of the country’s annual gold demand. For Valentine’s and Mother’s Day, Americans spend more on jewelry than any other type of gift, purchasing nearly $10 billion of jewelry for the two holidays in 2017.

For millions of workers, gold and diamond mining is an important source of income. But the conditions under which gold and diamonds are mined can be brutal. Children have been injured and killed when working in small-scale gold or diamond mining pits. Indigenous peoples and other local residents near mines have been forcibly displaced. In war, civilians have suffered enormously as abusive armed groups have enriched themselves by exploiting gold and diamonds. Mines have polluted waterways and soil with toxic chemicals, harming the health and livelihoods of whole communities.

Jewelers and watchmakers typically rely on complex supply chains to produce each piece of jewelry or watch. Gold, diamonds, and other minerals and gemstones are mined in dozens of countries around the world, and are then typically traded, exported, and processed in other countries. Processed gold and polished diamonds are then transformed into jewelry in manufacturing plants and artisan workshops, before reaching retailers. By the time a piece of jewelry is offered for sale, it may be very difficult to know the origins of the gold or diamonds it contains, or whether they are tainted by human rights abuses or environmental harms.

Despite this complexity, jewelry companies have a responsibility to ensure that their businesses do not contribute to human rights abuses at any point in their supply chains. Under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, an international standard on human rights responsibilities of companies, businesses have to put in place “human rights due diligence”—a process to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for their own impact on human rights throughout their supply chain. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has developed this approach further in its “Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas,” the leading due diligence standard for minerals.

Consumers increasingly demand responsible sourcing too. A growing segment of younger consumers are concerned about the origins of the products they buy, and want to be sure that the jewelry they purchase has been produced under conditions that respect human rights.

In this report, Human Rights Watch scrutinizes steps taken by key actors within the jewelry industry to ensure that rights are respected in their gold and diamond supply chains. The report focuses on the policies and practices of 13 major jewelry brands, selected to include some of the industry’s largest and best-known jewelry and watch companies and to reflect different geographic markets: Boodles (United Kingdom), Bulgari (Italy), Cartier (France), Chopard (Switzerland), Christ (Germany), Harry Winston (United States), Kalyan (India), Pandora (Denmark), Rolex (Switzerland), Signet (United States-based parent company of Kay Jewelers and Zales in the US, Ernest Jones and H. Samuel in the UK, and other jewelers), Tanishq (India), Tribhovandas Bhimji Zaveri Ltd. (TBZ Ltd.)(India), and Tiffany and Co. (US). Collectively, these 13 companies are estimated to generate over $30 billion in annual revenue.

Human Rights Watch first contacted these 13 companies with letters and requested meetings with each company. Ten companies responded. Nine sent written responses. Of those, six companies agreed to meet with Human Rights Watch. Another company met with Human Rights Watch without sending a letter. Three companies did not respond, despite repeated requests. Human Rights Watch analyzed the actions taken by the jewelers based on information provided directly by the companies, as well as publicly available information from company websites and other public sources. We also assessed the governance, standards, and certification systems of the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), an industry-led initiative with over 1,000 members, including jewelry manufacturers and retailers, refiners, and mining companies.

Our research found that most of the 13 jewelry companies we contacted directly recognize their human rights responsibilities and have made some efforts to responsibly source their gold and diamonds. However, their practices differ significantly.

Some of the companies scrutinized for this report have taken important steps to address human rights risks in the gold and diamond supply chain. For example, Tiffany and Co. can trace all of its newly mined gold back to one mine of origin and conducts regular human rights assessments with the mine. Cartier and Chopard have full chain of custody for a portion of their gold supply. Bulgari has conducted visits to mines to check human rights conditions. Pandora has published detailed information about its human rights due diligence efforts, including on noncompliance found during audits of its suppliers and steps it is taking to address them. In addition, two companies we contacted have pledged to take specific steps to improve their practices going forward. Boodles has pledged to develop a comprehensive code of conduct for its gold and diamond suppliers, and to make it public. The company has also pledged to report publicly on its human rights due diligence from 2019, and to conduct more rigorous human rights assessments. Christ has pledged to publish its supplier code of conduct and other information on its human rights due diligence efforts in the coming year.

While these are promising signs, we found that most companies still fall short of meeting international standards. While some companies are actively working to identify and address human rights risks in their supply chains, others rely simply on the assurances of their suppliers that their gold and diamonds are free of human rights abuses, without rigorously verifying these claims. Some have made no commitments to responsible sourcing at all. Almost none can identify the specific mines where all of their gold and diamonds originate. Few provide comprehensive public reports on their efforts to responsibly source gold and diamonds.

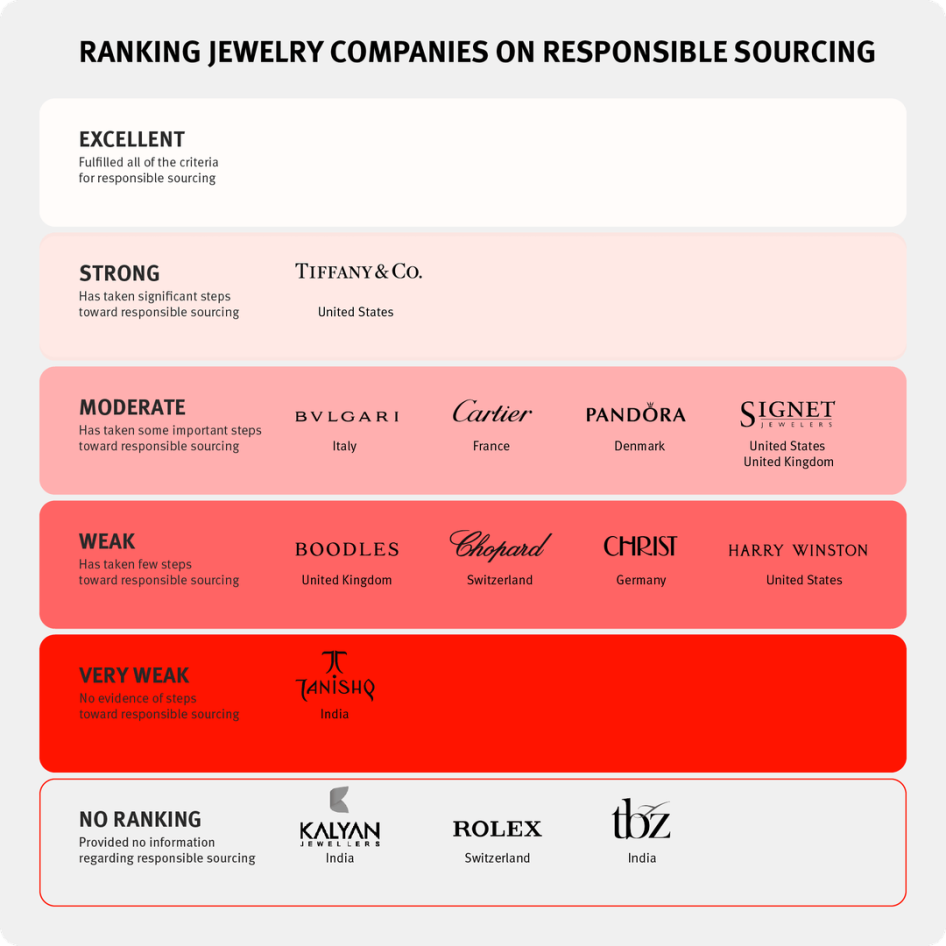

Based on information provided to us by the companies directly and publicly available information, we assess the company’s responsible sourcing policies and practices as follows:

Excellent (Companies that fulfill all of the criteria for responsible sourcing:)

None

Strong (Companies that have taken significant steps towards responsible sourcing): Tiffany and Co.

Moderate (Companies that have taken some important steps towards responsible sourcing): Bulgari, Cartier, Pandora, Signet

Weak (Companies that have taken few steps towards responsible sourcing):

Boodles, Chopard, Christ, Harry Winston

Very weak (Companies for which there was no evidence of steps towards responsible sourcing): Tanishq

No ranking due to nondisclosure (Companies that provide no information regarding responsible sourcing): Kalyan, Rolex, TBZ Ltd.

Our research also found that many companies are over-reliant on the Responsible Jewellery Council for their human rights due diligence. The RJC has positioned itself as a leader for responsible business in the jewelry industry, but has flawed governance, standards, and certification systems. Despite its shortcomings, many jewelry companies use RJC certification to present their gold and diamonds as “responsible.” This is not enough.

While the industry has a long way to go, some exciting initiatives have emerged in recent years to show that change is possible. The Canadian jeweler Fair Trade Jewellery Co. has recently started to import fully-traceable gold from artisanal mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo. A growing number of small jewelers in the UK and elsewhere are sourcing their gold from artisanal mines in Latin America that are certified under the Fairtrade or the Fairmined gold standard. And a Canadian diamond company, the Dominion Diamond Corporation, has introduced a line of traceable diamonds called CanadaMark, which are independently tracked at every stage from the mine to polished stone.

To move forward, all jewelry companies need to put in place strong human rights safeguards—otherwise, they risk contributing to human rights abuses. In particular, companies should:

- Put in place a robust supply chain policy that is incorporated into contracts with suppliers;

- Establish chain of custody over gold and diamonds by documenting business transactions along the full supply chain back to the mine of origin, including by requiring suppliers to share detailed evidence of the supply chain;

- Assess human rights risks throughout their supply chains;

- Respond to human rights risks throughout their supply chains;

- Check their own conduct and that of their suppliers through independent third-party audits (a systematic and independent examination of a company’s conduct);

- Publicly report on their human rights due diligence, including risks identified;

- Publish the names of their gold and diamond suppliers;

- And source from responsible, rights-respecting artisanal and small-scale mines.

To be credible, the Responsible Jewellery Council should become a true multi-stakeholder body by giving civil society and industry representatives equal decision-making power at all levels and strengthening its standards and auditing practices to set a higher bar for responsible sourcing practices by the industry.

Cases

Ghana

A Human Rights Watch team met “Peter,” age 15, at an artisanal and small-scale gold mine in Odahu, Amansie West district, Ghana’s Ashanti region in March 2016. Peter and several other children were digging ore out of deep, unsecure pits that were placed underneath a mass of hard rock. Peter also used toxic mercury, without being aware of the health risks. Peter described his life:

“I am working at the old Chinese mining site. I bring the load up from the ground, I dig. I also do the washing [processing of the gold ore]. I use mercury, and get it from the gold buyer… I started about two years ago…. I use the money [I earn] to buy food and clothes, and give some to my mother. I am here every day, from 6 a.m. to 5 p.m…. I dropped out of school in P5 [5th grade of primary school]. I was unable to buy my things for school…. I wish I could have stayed in school.”

Philippines

In Jose Panganiban, in the Philippines, “Joseph,” 16, mines gold underwater, sometimes diving for hours, breathing through a tube. He told Human Rights Watch in November 2014:

I started working when I was 12. Sometimes I help pull out the bags, and sometimes I go underwater. It’s just like digging with a shovel, and putting it in a sand bag. [To breathe] I use the compressor…. I bite the hose and release it whenever I need air, inhale, and exhale through my nose…. At first, it was hard to think about going down… I don’t use goggles. I basically don’t use my eyes. I use my hands to look for the passage, the canal…. Sometimes you have to make it up fast, especially if you have no air in your hose if the machine stops working. It’s a normal thing [for the compressor to stop working]. It’s happened to me.I get a skin disease. It’s not itchy, and it doesn’t hurt. But the color of the skin changes. It gets red. I get it on my face…. I can smell [the fumes from the compressor] when they are transferring fuel. I can smell it because it travels down the hose…. If I work so hard underwater, I get tired.

Tanzania

In Chunya district, Tanzania in December 2012, Human Rights Watch interviewed “Rahim,” a 13-year-old boy who was involved in a mining accident. Rahim described his harrowing experience:

“I was digging with my colleague. I entered into a short pit. When I was digging he told me to come out, and when I was about to come out, the shaft collapsed on me, reaching the level of my chest … they started rescuing me by digging the pit and sent me to Chunya hospital.”

The accident, Rahim told Human Rights Watch, knocked him unconscious and caused internal injuries. He remained in the hospital for about a week and over a year later still occasionally felt pain in his abdomen.

Central African Republic

In November 2016, a resident from Bria, Central African Republic, told Human Rights Watch that fighters from two factions of the Seleka armed group—both of which have committed numerous war crimes—fought over control of roads leading to diamond mines around Kalaga, in the eastern Central African Republic. The two armed groups are the Popular Front for the Renaissance in the Central African Republic (Front Populaire pour la Renaissance de la Centrafrique, FPRC) and the Union for Peace in the Central African Republic (l'Union pour la Paix en Centrafrique, UPC). Human Rights Watch has documented serious crimes committed by these groups. Fighters from one of the factions, the Popular Front for the Renaissance in the Central African Republic deliberately targeted civilians from the Peuhl ethnic group, including two injured Peuhl men who were receiving treatment at the main hospital in the town of Bria, Haute Kotto province. FPRC fighters killed the two men outside the hospital’s main entrance. An injured Peuhl witnessed the killings and told Human Rights Watch:

“We were on the hospital grounds, but not yet in the buildings. Men came to take us. They took two men, Amadou and Halidou, outside and killed them with guns and machetes.”

The FPRC eventually gained access to the mines in Kalaga. Rebel commanders told Human Rights Watch that access to diamond mines was crucial to their operations.

I. Introduction

The Supply Chains for Gold and Diamonds

The Diamond Supply Chain

Approximately 130 million carats of rough diamonds are mined every year, including both gem-quality and industrial diamonds; about 70 percent, or 90 million carats, are gem quality.[1] Russia, Botswana, Canada, and Australia are the world’s largest diamond producers, and the 10 largest mines account for over half of the world’s diamond production.[2] Approximately 20 percent of gem-quality diamonds come from artisanal mines.[3]

The diamond industry is dominated by two giant mining companies, ALROSA, a Russian company, and De Beers, which operates mines in Botswana, Canada, Namibia, and South Africa. These two companies account for over half of the world’s rough diamond sales. A handful of other mining companies–Rio Tinto, Dominion, and Petra–each have smaller shares of the diamond market.[4]

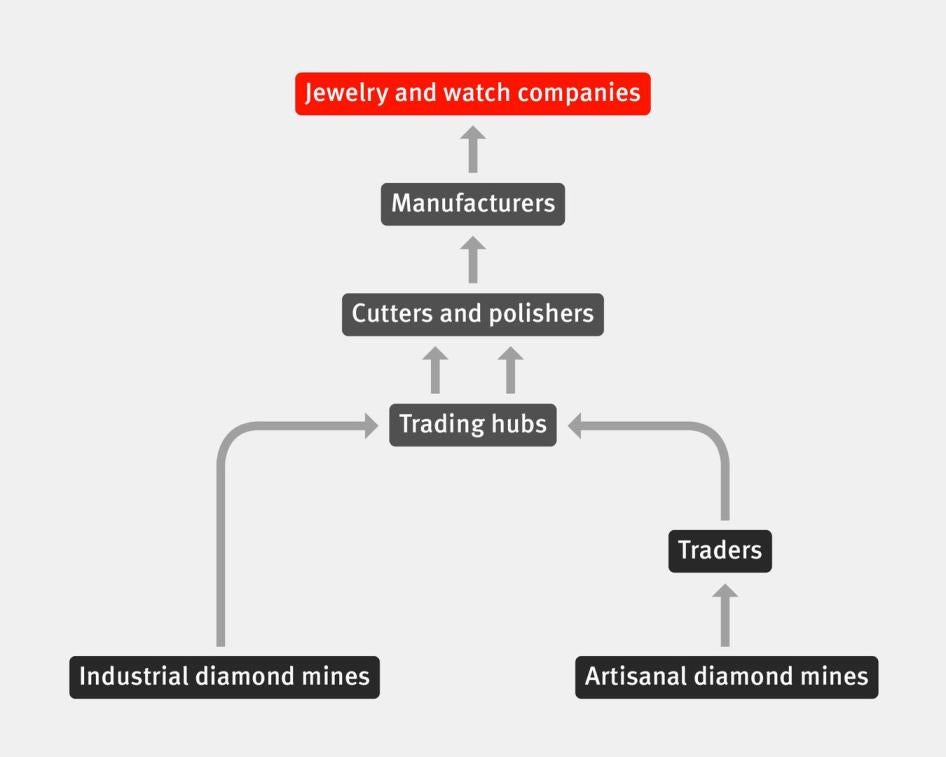

After rough diamonds are mined, they typically are exported to diamond trading hubs (or exchanges,) where they are sorted according to shape, color, size, and carat. The largest diamond trading hubs are in Antwerp and Dubai. Diamonds may be traded multiple times before they are sent to cutters and polishers. They may also be sent both in rough and polished form between several jurisdictions before being purchased and made into jewelry and watches; sometimes this involves mixing of shipments.[5] At least 70 percent of diamonds are cut and polished in India, largely because of low labor costs, while approximately 20 percent are cut and polished in China.[6] Once diamonds are cut and polished, they are sent to jewelry manufacturers, and finally, to retailers. The United States is the largest market for diamond jewelry, accounting for over 40 percent of the world’s demand for polished diamonds.[7]

Mining companies often do not disclose the mines of origin for the diamonds they sell. For example, both De Beers and ALROSA, the two largest diamond producers, aggregate diamonds from multiple mines before selling them to their customers.[8] De Beers sells rough diamonds from eight mines located in four countries (Botswana, Canada, Namibia, and South Africa). The company states that it provides clients with “complete and unequivocal assurance” that its diamonds are responsibly sourced from its own or joint venture mines, but does not identify the mine or country of origin for individual diamonds.[9]

The Gold Supply Chain

Gold is mined in around 80 countries, with approximately 3,200 tons produced every year.[10] The largest producers are China, Australia, Russia, and the US.[11] Most gold comes from large, industrial mines, though 15 to 20 percent of the world’s gold comes from small-scale or artisanal mines, primarily in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.[12] Jewelry accounts for over 50 percent of the world’s gold demand, an estimated 1,600 tons of gold for 2016.[13]

The world’s largest industrial gold mining companies include Barrick Gold Corporation (Canada), Newmont Mining (US), AngloGold Ashanti Limited (South Africa), Goldcorp Inc. (Canada), and Kinross Gold Corporation (Canada).[14] These companies operate large-scale mining operations that are highly mechanized. Artisanal and small-scale mining, by contrast, is labor intensive, with simple machinery.

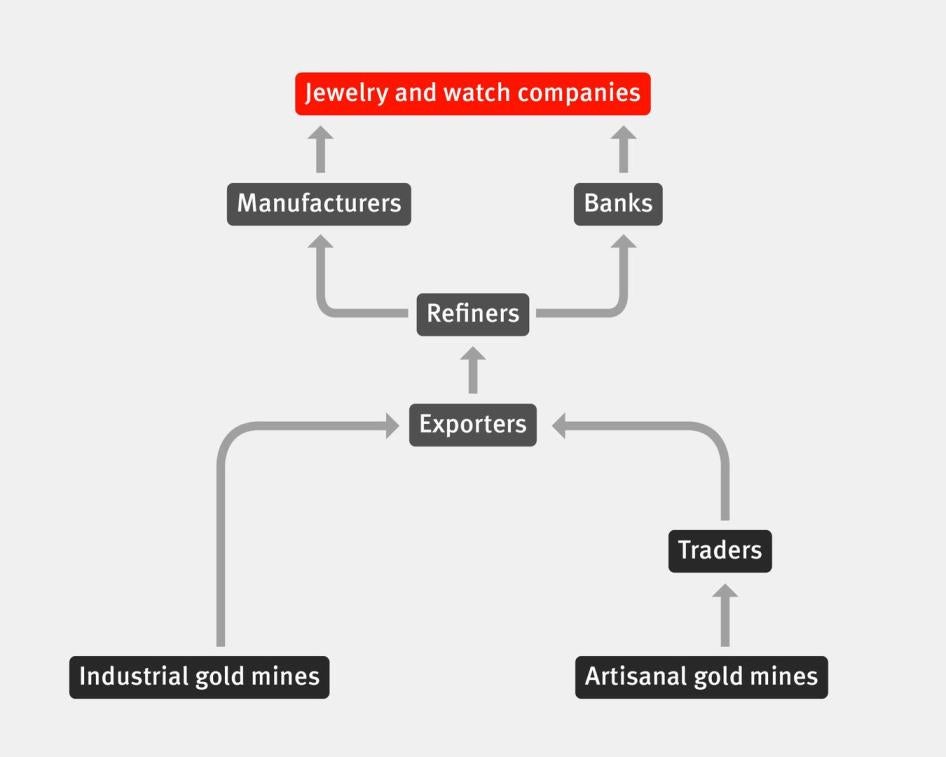

Gold from industrial mines may be exported directly to refiners, while artisanal gold may pass from one trader to another before being exported for refining. Gold refiners play a crucial role in the gold supply chain. Because the vast majority of the world’s gold passes through a small number of refiners, these companies are sometimes called the “choke point” of the gold supply chain.[15] For example, just four companies based in Switzerland—Valcambi, Metalor, Produits Artistiques Métaux Précieux (PAMP), and Argor-Heraeus—refine more than half of the world’s gold.[16]

Once gold is refined, it is sold to banks, manufacturers, jewelry and watch companies, electronics companies, or other businesses. Jewelry companies may source their gold directly from refiners, or from manufacturers, banks, or international gold traders. China and India are the largest markets for gold jewelry, representing over 50 percent of global jewelry demand.[17]

Human Rights Abuses in the Gold and Diamond Supply Chain

Around the world, millions of people work in gold and diamond mining. The vast majority of them—an estimated 40 million people—work in artisanal and small-scale mines, which operate with little or no machinery and often belong to the informal sector.[18] Artisanal and small-scale mining is often an important source of livelihood for these populations and accounts for 15 to 20 percent of the world’s gold. Industrial mining operations are also major employers; around one million people work in industrial gold mining operations.[19]

However, mining has also contributed to human rights abuses. Human Rights Watch and other civil society groups have documented a wide range of human rights abuses in the context of gold and diamond mining, including labor rights abuses, conflict-related abuses against civilians, violations of the right to environmental health, and other violations.

The Worst Forms of Child Labor

An estimated one million—and possibly many more—children work globally in artisanal and small-scale mining, in violation of international human rights law, which defines work underground, underwater, or with dangerous substances as hazardous and, therefore, among the worst forms of child labor and prohibited for children.[20] These prohibitions are clearly reflected in the domestic laws of many countries where hazardous child labor nonetheless continues to persist. Children who work in mining are often exposed to extreme danger. Many children work in deep, unstable pits; some have been injured or even killed in accidents. Children suffer respiratory disease from inhaling dust, pain and back injury from the lifting of heavy rocks, and other health conditions from mining. In artisanal and small-scale gold mines, children may be exposed to toxic mercury, which is used for gold processing, and can cause lifelong brain damage and other irreversible conditions.

Human Rights Watch has documented the use of hazardous child labor in gold or diamond mining in Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, the Philippines, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe.[21] Other independent investigations have documented hazardous child labor in gold mines in Burkina Faso, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Indonesia.[22]

Forced Labor and Human Trafficking

In some gold and diamond mines, adults and children have become victims of forced labor and human trafficking. Forced labor is understood as a situation where an individual works involuntarily and under “menace of penalty.”[23] Those who attempt to leave may face violence and other abuse. Human trafficking occurs when a person is recruited or transported by force, threat, or deception for the purpose of exploitation.[24]

Human Rights Watch found that in Eritrea, for example, conscripts for the national service program were forced to work indefinitely for a subcontractor of a Canadian gold mining company. Workers have initiated a law suit against the company.[25] In Zimbabwe, from 2008 to 2014, workers were forced by the military to work in diamond mining.[26] Other studies have documented forced labor in gold mines in Peru and the Democratic Republic of Congo.[27]

Environmental Harm

Gold and diamond mining operations have sometimes caused serious environmental damage and threatened people’s rights to health, water, food, and a healthy environment.[28] For example, large-scale industrial mines have caused dangerous pollution through the dumping of tailings (mine residue), leakages, and accidents.[29] An example is the 2014 mining disaster at the Canadian Mount Polley gold (and copper) mine, in which toxic tailings were unleashed into a lake and other waterways due to a tailings pond failure.[30]

Artisanal and small-scale mining has also caused environmental harm. For example, small-scale gold mines emit annually an estimated 1,400 tons of mercury, a toxic metal that is used in gold processing but causes damage to the nervous system and can kill. The resulting pollution of air, water, and soil constitutes a global environmental threat and has resulted in negative health effects for workers and local communities living near such gold mines.[31] In Nigeria, artisanal gold mining has caused unintentional releases of lead that has killed over 400 children.[32]

Land Rights and Indigenous People’s Rights Violations

In some cases, international mining companies and governments have abused the rights of local residents when clearing land for exploration and mining.[33] In Zimbabwe, for example, the government has been accused of forcibly displacing villagers to make way for diamond mining in Marange.[34]

Mining operations have also caused violations of the rights of indigenous peoples. International gold companies in Uganda, for example, failed to secure free, prior, and informed consent from indigenous Karamojong communities in Uganda before doing exploration, in violation of international human rights standards.[35] Amnesty International reported that the Mount Polley mining disaster in Canada negatively affected the traditional livelihood of indigenous peoples—salmon fishing—and destroyed sacred lands and traditional medicines.[36] When indigenous people in some countries have protested against mining operations, they have sometimes faced repression and even been killed.[37]

Armed Conflict Violations, Including Killings and Sexual Violence

Gold and diamond companies have also been directly linked to violations of international humanitarian law, which applies to situations of armed conflict. In particular, gold and diamond mining and trade have helped finance violent and abusive armed groups, including through money laundering.

For example, investigations by Human Rights Watch and other nongovernmental organizations have documented how the illegal gold trade in the Democratic Republic of Congo has benefited armed groups responsible for horrific crimes against civilians, including massacres and systematic sexual violence.[38] Other research has shown the link between diamond mining and human rights abuses in conflict-torn Central African Republic. Here, armed groups responsible for killings of civilians and other war crimes benefited from the diamond trade, and competing rebel factions have attacked diamond mining areas to obtain control over the business and loot diamond dealers. In November 2016, while fighting for control over roads leading to diamond mines around Kalanga, one faction deliberately targeted and killed Peuhl civilians in the area.[39] Gold mining has also helped fund armed groups in Colombia.[40]

Abusive government armed forces also have benefited from mining. For example, in Zimbabwe, army brigades were sent to the diamond mines to ensure access to mining revenue by senior members of the ruling party and the army itself between 2008 and 2014.[41] In Angola during 2015, soldiers and private security guards were accused by human rights activists of torturing and killing civilians in their quest to control diamond mining operations.[42]

II. Existing Standards–And Why They Are Not Enough

Companies have human rights responsibilities. These responsibilities have been spelled out in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, an international standard that was endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011 and has since been widely recognized by companies. Under the Guiding Principles, companies are expected to take proactive steps to ensure that they do not cause or contribute to human rights abuses within their global operations, and respond to human rights abuses when they occur. This responsibility extends beyond companies’ direct operations to include their global supply chains.

The Guiding Principles require companies to put in place human rights due diligence—that is, a process to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for companies’ impacts on human rights—throughout their supply chain.[43] Businesses should monitor their human rights impact on an ongoing basis and have processes in place to remediate adverse human rights impacts they cause or to which they contribute.[44]

Some companies engage in philanthropy or social programs outside their own operations as part of their commitments to corporate social responsibility. Such charitable endeavours are largely unrelated to the question of whether a company is living up to its human rights responsibilities under the UN Guiding Principles.

In addition to the UN Guiding Principles, several global standards have been developed specifically for precious metals and stones, including the Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, and two standards by the Responsible Jewellery Council.

While the UN Guiding Principles and industry-specific standards can play a role in guiding companies towards responsible sourcing, they all suffer from a number of weaknesses, notably their voluntary nature and a lack of strong monitoring and enforcement mechanisms. Many voluntary initiatives are also undermined by poor and intransparent audits.

Very few countries have laws requiring companies to conduct mandatory human rights due diligence in their supply chain. In 2010, the United States passed conflict minerals legislation, in section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act, requiring companies to conduct due diligence for minerals originating from the Democratic Republic of Congo and surrounding countries. However, in June 2017, the US House of Representatives voted to repeal this provision, and in September, approved a bill that would cut funding for implementation and enforcement of the provision; its future now depends on the decision by the US Senate.[45] The European Union has passed a Minerals Regulation that will enter into force from 2021. It will oblige companies importing gold, tin, tungsten, and tantalum into the European Union to conduct due diligence to ensure that they are not contributing to conflict-related abuses or other violations.[46]

OECD Due Diligence Guidance – A Key Standard, Poorly Implemented

The most widely accepted standard in the precious minerals sector is the OECD’s “Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas.”[47] It builds on the concept of human rights due diligence developed in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights—i.e. a process to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for a company’s impact on human rights throughout their supply chain. The OECD Guidance lays out five steps for risk-based due diligence: 1) strong management systems, including systems to establish chain of custody;[48] 2) identification and assessment of risks in the supply chain; 3) a strategy to respond to identified risks; 4) third-party audits of supply chain due diligence; and 5) public reporting on supply chain due diligence.

The OECD Due Diligence Guidance applies to the sourcing of all minerals (including diamonds) and implicates a broad range of human rights. It is not limited to conflict regions but applies to all areas that are “high-risk,” such as areas of political instability, repression, institutional weakness, insecurity, collapse of infrastructure, widespread violence, violations of national or international law, or “other risks of harm to people.”[49] The Guidance also applies to all actors in the supply chain; for gold, it distinguishes between “upstream” companies such as mines, gold traders in the country of origin, and international gold refiners, and “downstream” companies, such as international gold traders, bullion banks, jewelers, and other retailers.[50] The standard has inspired a number of other standards for specific regions, actors, or minerals.[51]

However, the OECD Due Diligence Guidance is voluntary and suffers from a lack of monitoring and implementation. States have committed to help put in place the Guidance, but failed to put in place mechanisms to track implementation—or lack thereof—by companies in their country.[52] Civil society groups have found that companies often fail to put the OECD Due Diligence Guidance into practice.[53]

The OECD Due Diligence Guidance requires all companies in a supply chain, including jewelers and watch companies, to conduct due diligence on their suppliers when sourcing from conflict-affected and high-risk areas. But in practice, this often does not happen. Most of the companies assessed for this report told Human Rights Watch that they did not request detailed information from suppliers on their due diligence and the human rights issues identified. As a result, they could not undertake robust and meaningful risk management.[54]

The Kimberley Process—An Inadequate Model

The Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) is the most prominent international standard with regards to diamonds.[55] The KPCS is a government-led international certification scheme, launched in 2003 to prevent trade in “conflict diamonds,” which it narrowly defines as rough diamonds used by rebel movements to finance wars against legitimate governments. Under the KPCS, member states have to set up an import and export control system for rough diamonds. The scheme requires documentation of the country of origin, but not of mines of origin.

The Kimberley Process suffers from a number of weaknesses.[56] First, it relies on an indefensibly narrow “conflict diamond” definition that only focuses on abuses perpetrated by rebels, ignoring those of state actors or private security firms. For example, the Kimberley Process has authorized exports of Angolan and Zimbabwean diamonds despite their being mined under highly abusive conditions.[57] Second, it applies only to rough diamonds, allowing stones that are fully or partially cut and polished to fall outside the scope of the initiative. Many diamond shipments that pass through trading hubs are also mixed with diamonds from other countries of export, thereby rendering the diamonds untraceable to either their initial country or mine of origin. Third, over time the Kimberley Process has proven itself reticent to impose sanctions on countries found noncompliant with Kimberley Process minimum requirements, other than in the most egregious and indisputable instances such as in war-torn Central African Republic. Finally, the World Diamond Council’s System of Warranties, meant to support the KPCS, relies on written or oral assurances by diamond suppliers, rather than independent and transparent monitoring.

Due to these weaknesses, civil society groups have suggested that the OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance—which is not limited to conflict areas—become the core standard for the diamond sector.[58] Industry groups, including jewelers like Signet and Tiffany and Co., have also stated publicly that the mandate of the Kimberley Process is too narrow, and should be expanded to include non-conflict-related abuses.[59] However, spokespeople for the diamond industry have been reluctant to explicitly endorse the OECD Due Diligence Guidance, and focused instead on improving the System of Warranties.[60]

The Responsible Jewellery Council—A Weak Assurance

The Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) brings together more than 1,000 companies in the jewelry industry, including jewelers, manufacturers, refiners, mining companies, and others. It was founded in 2004 by a small group of 14 companies and trade associations interested in increasing consumer confidence that the jewelry they purchase is produced responsibly.[61] RJC members commit to and are audited against the Code of Practices, a standard that outlines responsible business practices for the jewelry supply chain; companies can also join an additional optional standard, the Chain-of-Custody Standard. Membership of the RJC, however, is no guarantee that a company’s jewelry is responsibly sourced.[62] The RJC’s governance, standards, and system of audits are flawed, allowing companies to be RJC-certified even if they fail to meet basic human rights standards.

The RJC board is composed solely of 25 industry representatives from different positions in the supply chain, from mine to retail.[63] The board appoints the chief executive officer, approves new or revised RJC standards and certification models, and takes other key decisions. The RJC consults civil society and other actors and includes civil society representatives on its standard-setting committee, but is essentially an industry body.[64] Its decision-making bodies do not include consumer groups, representatives of mining communities (for example, organizations addressing land rights or environmental harms), trade unions or miners’ associations, or human rights nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

In late 2017, the RJC was reviewing both its standards; the new version of the Code of Practices is expected to include more specific requirements for human rights due diligence as spelled out in the OECD Due Diligence Guidance. Reform may be particularly urgent for RJC member companies now, as the European Union has made clear that it will recognize only refiners operating according to OECD-aligned standards as “responsible” for its minerals regulation entering into force in 2021.[65]

The Code of Practices

The RJC requires all its members to comply with its Code of Practices, a standard that addresses human rights, labor rights, environmental impact, and mining practices in the jewelry supply chain. In order to be certified against the Code, a company needs to undergo an independent audit that confirms the company is in compliance.

The Code of Practices requires companies to have a human rights due diligence process that seeks to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for human rights impacts, in line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. However, the Code of Practices provides little detail on how supply chain due diligence should be implemented. It makes no reference to the OECD Due Diligence Guidance—the international standard for due diligence in the minerals sector—and provides no detail on what steps companies should take to conduct due diligence themselves, or what evidence companies should require from their suppliers in this regard.[66] According to an RJC auditor, suppliers only need to pledge that they conduct strong human rights due diligence, but do not provide any evidence for this.[67] Neither does the Code of Practices require jewelers—or other downstream companies—to have traceability or chain of custody of their gold or diamonds.[68] The Code of Practices is also weak in other substantive areas, for example, on indigenous peoples’ rights and on resettlement.[69]

RJC members are given two full years to comply with the standard after joining, but benefit from the reputation of the RJC in the interim.[70] For example, in March 2017, the RJC had 342 members who had not (yet) completed the audit process that certifies compliance with the Code of Practices.[71]

In addition, companies can join at any level of their operations. For example, a small subsidiary office of a large jewelry company could apply for RJC membership, without including the rest of the company’s entities.[72] If the subsidiary’s name is similar to the larger group, the entire group may enjoy a reputational benefit even when most entities do not comply with the standard—an issue that the RJC itself has recognized as a potential problem.[73] Another loophole is that the Code of Practices allows companies to exclude facilities from the scope of its certification where it does not have full control, meaning more than 50 percent ownership.[74] As a result, certification may exclude operations of significant size. For example, Rio Tinto has excluded the Grasberg gold mine in Indonesia, of which it owns 40 percent, from its RJC certification scope.[75] The Grasberg mine has been the site of numerous deaths of workers and other labor rights issues.[76]

Finally, the Code of Practices does not require companies to publicly report on the concrete steps they have taken to conduct due diligence—a core requirement of the OECD Guidance. Its reporting obligations are vague and do not mention due diligence or the need for companies to report on the steps they have taken to identify, assess, and mitigate risks in their supply chains.[77]

The Code of Practices is currently under review, and a new version of the Code—announced for the end of 2018—is expected to include more specific requirements for human rights due diligence as spelled out in the OECD Due Diligence Guidance.[78]

The Chain-of-Custody Standard

A second RJC standard, the Chain-of-Custody Standard, promotes traceability and is more rigorous, but adherence to it is optional for RJC members. By early 2018, only 48 of over 1,000 member companies had certified entities under the standard, including 13 jewelers.[79] The Chain-of-Custody Standard requires companies to establish documentary evidence of business transactions along the supply chain and to confirm they are not causing adverse impacts in conflict-affected and high-risk areas.[80] While the revised 2017 Chain-of Custody-Standard seeks to align with the OECD Due Diligence Guidance, it still falls short of the Guidance in some areas.

Crucially, the standard applies to gold and platinum, but not to diamonds, thereby excluding a significant part of the jewelry industry and allowing the diamond supply chain to be treated as an exception.

In addition, the standard does not require a comprehensive human rights due diligence process through identification and mitigation of risks, as set out by the OECD Due Diligence Guidance. Rather, the Chain-of-Custody Standard narrowly focuses on documentation of the supply chain through “know your customer” procedures, and even this is limited: Companies are not required to know the mine of origin or country of origin for their material; it suffices to have material that is declared “eligible.”[81]

The Chain-of-Custody Standard also does not require companies to put in place chain of custody for all their operations or all their material, as the name might suggest. Instead, companies are allowed to select some “entities” under their control for certification, leaving other entities of a company uncertified. While this may allow for companies to gradually switch over to more responsible sourcing practices, the current practice also carries the risk that a whole company enjoys the reputational benefit when the majority of operations is not in compliance with the standard. Furthermore, companies are only required to segregate “eligible” material (material meeting the Chain-of-Custody Standard) and “non-eligible” material as it travels through the supply chain, but not to share information on the percentage of material that meets the standard, possibly allowing entities to be certified even if only a small fraction of their material meets the standard.[82]

The Audit Process

All RJC member companies have to undergo an audit to demonstrate that they are compliant with the Code of Practices, and to receive certification.[83] Those companies that choose to obtain certification for the Chain-of-Custody Standard have to undergo a separate audit.

Audits are based primarily on a review of the company’s written policies and documentation, and visits to a “representative set” of facilities.[84] The process has significant shortcomings. It is not an in-depth examination about whether the company actually implements or abides by its policies throughout its operations. For example, large companies may have operations in multiple countries, and rely on many suppliers, but still may receive RJC certification based on visits to only a few facilities under its direct control without any examination of many others. Gold and diamond mines typically are only visited if a mining company or individual mine is seeking certification; they generally are not included in audits for any downstream companies, such as jewelers.[85] Although audits are supposed to include questions on a broad range of human rights, auditors are not always qualified human rights experts.[86]

Once the auditors complete their report, they only submit a summary report of the audit to the RJC, not the full audit report, which is shared only with the company. Based on the summary report and the auditor’s recommendation, the RJC then determines whether a company should be certified. The RJC does not make the audit or its summary public.[87] It publishes only basic data about the company, the facilities included in the scope of certification, and the fact that an audit took place. External stakeholders have no way of knowing what facilities were visited; how the visit was conducted; how compliance with human rights standards was assessed; what noncompliances were found; or what corrective actions might be required. The lack of transparency in RJC audits makes it very difficult for communities, workers, consumers, or other stakeholders to know precisely what was audited and the results of it, which undermines confidence in the certification system and makes it difficult for any party, including the RJC, to credibly evaluate the performance of the company.

Human Rights Watch research has shown that certified RJC member companies can source gold or diamonds mined under abusive conditions, even as they were deemed compliant with the RJC’s standards. A 2014 investigation by Human Rights Watch found that the Swiss refinery Metalor had sourced from a Ghanaian export company that bought gold from traders all over Ghana, who in turn frequently bought gold at unlicensed artisanal sites where child labor occurred. The export company openly acknowledged that it had no human rights due diligence in place and could not guarantee that its gold was child-labor free.[88] In 2015, Metalor stopped sourcing gold from the artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector in Ghana.[89]

Human Rights Watch concludes that RJC certification provides little assurance that a company’s products are responsibly sourced.

III. How Jewelry Companies Can Source Responsibly

Key Elements of Responsible Sourcing

The term “responsible sourcing” is used frequently, but may have different meanings in different contexts. Based on our research and relevant standards (in particular, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Due Diligence Guidance, including its Gold Supplement), we believe the following elements are critical to responsible sourcing by jewelry and watch companies:

- Adoption and implementation of robust supply chain policies—based on international human rights and humanitarian law, international labor standards and the OECD Due Diligence Guidance—that are incorporated into all contracts with suppliers;[90]

- Traceability or chain of custody over gold and diamonds, including efforts to trace these minerals to their mines of origin by requiring full supply chain documentation from suppliers;[91]

- Assessment of all human rights risks throughout the supply chain, including evidence of human rights due diligence by upstream suppliers, such as on-the-ground mine assessments;[92]

- Concrete steps to mitigate all identified human rights risks, including by severing contracts with noncompliant suppliers;[93]

- Third-party audits of the company’s and its suppliers’ human rights due diligence by auditors qualified to assess human rights issues;[94]

- Annual public reporting on their human rights due diligence, including steps to manage and mitigate risks;[95]

- Publishing on an annual basis the names of their suppliers of precious metals and gems.[96]

|

Consumer Demand for Responsible Jewelry Market research finds that a growing segment of consumers that purchase jewelry—and, in particular, younger “millennials” aged 18 to 34—are concerned about its origins. A 2016 survey of 75,000 customers in the top markets for diamond jewelry found that 36 percent of millennials (compared to 27 percent of older singles) said that the feature of diamond rings they were “least likely to compromise on” was responsible sourcing.[97] In 2015, millennials purchased US$26 billion in diamond jewelry in the top 4 markets for diamond jewelry combined (US, China, India, and Japan), accounting for 45 percent of diamond jewelry sales in those countries.[98] |

In addition, Human Rights Watch believes that jewelry companies should support and source from responsible, rights-respecting artisanal and small-scale mines.[99] While labor abuses are widespread in the sector, artisanal mines provide income for millions of workers and thousands of mining communities. Human Rights Watch believes that the jewelry industry should strive to ensure that their efforts to mitigate supply chain human rights risks do not lead them to simply exclude all artisanal suppliers from their supply chains as the “path of least resistance.” Instead, they should support efforts to formalize and professionalize artisanal mines and improve working conditions.

Human rights due diligence comes at a cost, and therefore poses challenges for companies in the supply chain. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance recognizes this and is promoting cost-sharing within the industry.[100] That way, all companies along the supply chain share the financial burden.

Promising Practices

A number of initiatives have emerged that can help jewelers trace their gold and diamonds to mines of origin, and more responsibly source from the artisanal sector. These initiatives are often implemented in local mining communities, with the assistance of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and other stakeholders, including from the jewelry industry.

Traceability and Chain of Custody

An important element of responsible sourcing is to put in place chain of custody systems to trace gold and diamonds to their mines of origin, and systematically record this information, resulting in traceability of material. Traceability and chain of custody information are not guarantees that international human rights and environmental standards are respected in the mines of origin, but are useful tools for jewelers who seek to assess and monitor human rights risks at the mine level.

In June 2017, the Canadian jeweler Fair Trade Jewellery Co. successfully imported the first fully-traceable gold from artisanal mines in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where artisanal gold is routinely smuggled to international markets.[101] The artisanal mines are supported by IMPACT (formerly called Partnership Africa Canada), a Canadian NGO, that set up the so-called “Just Gold” project to develop traceability and OECD-aligned due diligence. The project provides technical support to miners who are willing to improve their practices and channel their gold to legal exporters. About 600 adult miners have been registered at six mine sites; children cannot register.[102]

A Canadian diamond company, the Dominion Diamond Corporation, has introduced a line of traceable diamonds called CanadaMark.[103] These diamonds can be traced back to two mines in northwestern Canada. Customers can send in a diamond’s engraved serial number to request details.[104]

Sourcing from Certified Mines

Certification of specific mines against responsible sourcing standards can provide jewelers with greater assurance that the gold or diamonds they purchase from those mines are not tainted by human rights abuses. Nongovernmental organizations such as Solidaridad and IMPACT can play a key role in supporting mines to improve practices so they are able to comply with the standard; this may include steps to tackle child labor, improve environmental conduct, access finance, and establish direct contact with buyers.[105] Currently, there are few such certification options and the availability of gold and diamonds from certified mines is quite limited.

Gold

Two standards certify artisanal and small-scale gold mines that conform to human rights, labor rights, and environmental standards—the Fairmined Standard and the Fairtrade Gold Standard.[106] Both require third-party audits of individual mines.

The Fairmined Standard was introduced by the Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM) in 2014. Depending on the customer’s license with Fairmined, the gold may be fully traceable to the mine of origin, or may be mixed with other gold.[107] Availability of Fairmined gold is limited, however, with a total annual output of approximately 500 kilograms of gold per year.[108] This amount is just a small fraction of the gold used each year by several of the companies examined in this report.[109] As of early 2018, eight mines in four countries (Bolivia, Colombia, Mongolia, and Peru) were certified, with an additional 20 mining organizations working towards certification.[110] The Fairmined Gold Standard is currently developing a new “market entry” standard that seeks to assist artisanal gold mines in the process towards full certification.[111]

The Fairtrade Standard for Gold was launched in 2011. It is administered under the umbrella of Fairtrade International, and allows jewelers to trace their gold back all the way to the mine of origin.[112] Fairtrade’s first certified mines were in Peru. Over the last few years, the Fairtrade Foundation, Solidaridad, and other NGOs conducted a program of training and support to artisanal and small-scale gold miners in Africa, and in early 2017, certified an artisanal gold mine in Uganda.[113] Certified mines produced approximately 325 kilograms of gold in 2013-2014, and similar amounts more recently.[114] Fairtrade gold supplies a network of jewelers in Europe, Australia, and North America. In the United Kingdom, where the Fairtrade Foundation has a strong presence, many small jewelers have shown a strong interest in selling Fairtrade gold.[115] A Swiss public private partnership, the Swiss Better Gold Association, has linked up Swiss refiners, jewelry, and other gold companies with mines that are certified against the Fairmined and Fairtrade gold standards and has, together with NGOs and other actors, supported steps to improve conditions in gold mining.

Diamonds

In the artisanal diamond sector, the Development Diamond Initiative (DDI) is working to help register artisanal diamond miners, formalize the mining sector, and offer certification against the Maendeleo Diamond Standard.[116] Maendeleo is a Swahili word meaning “development” and “progress.” The Maendeleo Diamond Standard goes beyond the conflict focus of other diamond schemes, such as the Kimberley Process, by addressing labor conditions, child labor, health and safety, and environmental protection. Independent auditors visit the mining sites at random to verify compliance with the standard, and DDI provides support to miners to help improve their practices. In mid-2017, DDI was implementing the Maendeleo Diamond Standard in 14 mining communities in Sierra Leone, and had sold small quantities of diamonds to a buyer in Belgium.[117] It was also beginning implementation in the Democratic Republic of Congo.[118] A range of actors in the jewelry industry has supported the DDI, including De Beers, Tiffany and Co., Cartier, and Rio Tinto.[119]

In the future, the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) will offer jewelry companies another source of responsibly-sourced precious minerals and gems. IRMA was launched in 2006 to develop an independent standard for responsible mining, offering certification to individual mine sites, rather than mining companies.[120] IRMA’s focus is industrial, rather than small-scale or artisanal mines. The IRMA standard focuses on social and environmental practices of mines, and has been developed by a broad stakeholder group that includes mining companies, jewelers, and other “downstream users,” nongovernmental organizations, affected communities, and labor unions. In 2018, IRMA is offering a launch phase of certification for interested mines. During the launch phase, IRMA says it will evaluate and refine its systems, with a goal to offer mines full certification starting in 2019.[121] Tiffany and Co. helped launch IRMA, and says it plans to source from IRMA-certified mines, when feasible.

Batch Processing

One challenge for jewelers is ensuring that gold produced under responsible conditions is kept separate from other gold during the refining process. Commonly, gold refiners mix gold from multiple sources when they refine it. Many refiners are resistant to so-called “batch” or “segregated” processing, since it typically costs more.[122] Nevertheless, some refiners are willing to segregate gold for processing, often at extra cost. For example, refiners including PX Précinox (Switzerland), Metalor (Switzerland), S&P Trading (France), and Ögussa (Austria) all refine Fairmined gold, segregating it from the other gold that they process.[123]

Recycled Gold

Use of recycled gold can help avoid the human rights risks and environmental harms associated with newly-mined gold, as long as companies conduct due diligence; however, using recycled gold is not risk-free either, as it can be used for money laundering or wrongly labeled as recycled.[124] According to the World Gold Council, recycled gold accounts for approximately one-third of the total global supply of gold.[125] Jewelry, gold bars, and coins account for approximately 90 percent of post-consumer recycled gold, while the other 10 percent comes from industrial recycled gold, including electronics and cell phones.[126] Recycled gold can also refer to scrap material generated during refining or manufacturing, which is returned to a refiner or processor.

|

Small Jewelers Push for Change Small jewelers in the UK have recently come together and formed a group called Fair Luxury, or FLUX, with the goal of promoting responsible sourcing from rights-respecting mines.[127] The group organizes events to showcase positive sourcing practices and strategize on how to bring about broader change. Many FLUX members source their gold from Fairtrade certified mines. One of the first jewelers in this field has been Cred Jewellery, founded by Greg Valerio, a campaigner for fair trade jewelry, and now led by Alan Frampton. Cred says that, “We never do business with any mine until we have visited them ourselves to ensure that our customers receive the best assurance of where their gold is coming from.”[128] Another jeweler producing gold jewelry exclusively from Fairtrade gold is Anna Loucah, an award-winning goldsmith and designer whose jewelry has been worn by celebrities.[129] |

IV. Company Rankings and Performance

Methodology

When preparing this report, Human Rights Watch sent letters to the 13 companies profiled below, requesting information about their policies and practices in relation to human rights due diligence and the sourcing of their gold and diamonds. These 13 companies were selected to include some of the industry’s largest and best-known jewelry and watch companies and to reflect different geographic markets. Of the 13 companies, seven are based in Europe, three in the United States, and three in India. While these 13 companies are not necessarily representative of the entire industry, collectively, they generate an estimated US$30 billion in annual revenue, about ten percent of global jewelry sales.

Nine companies responded in writing to Human Rights Watch’s initial letters. The company responses varied widely, with some providing detailed information on their policies and practices, while others provided only general information on their approach to sourcing. An additional company met with Human Rights Watch by phone, but did not provide a written response. Three companies did not reply, despite repeated requests.

Human Rights Watch also requested meetings with each company, and spoke by phone or in person with senior staff of 7 of the 13 companies.[130]

The information provided below is based on information provided to Human Rights Watch directly from the companies, as well as publicly available information from company websites, annual reports, disclosure statements, and other public sources.

Human Rights Watch assessed the companies by evaluating what they were doing to achieve the following elements of responsible sourcing:

- Adoption and implementation of a robust supply chain policy—based on international human rights and humanitarian law, international labor standards, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Due Diligence Guidance—that is incorporated into all contracts with suppliers;

- Chain of custody over gold and diamonds, including efforts to trace these minerals to their mines of origin by requiring full supply chain documentation from suppliers;

- Assessment of all human rights risks throughout the supply chain, including evidence of human rights due diligence by upstream suppliers, such as on-the-ground mine assessments;

- Concrete steps to mitigate identified human rights risks, including by severing contracts with noncompliant suppliers;

- Third-party audits of the company’s and its suppliers’ human rights due diligence by auditors qualified to assess human rights issues;

- Annual public reporting on their human rights due diligence, including steps to manage and mitigate risks;

- Publication of names of gold and diamond suppliers on an annual basis.

In addition and as explained above, Human Rights Watch believes that jewelry companies should engage in efforts to support and source from responsible, rights-respecting artisanal and small-scale mines.

Based on a company’s performance with regards to these criteria, we have indicated whether the company is taking strong, moderate, weak, or very weak steps towards responsible sourcing. Companies that have not shared information are in a separate category due to nondisclosure.

Below is an overview of findings, followed by a detailed description of each company. Annex 1 contains a table with summary information on all companies in relation to the criteria.

Overview

Some of the jewelry companies examined have made important efforts to responsibly source their gold and diamonds, while others have taken much weaker measures, or disclose nothing about their efforts to source gold and diamonds responsibly. While there are significant differences in the companies’ approaches, Human Rights Watch found that none of the companies fully meet our criteria for responsible sourcing. Among the key problems are a failure to assess human rights risks, a lack of public reporting, and an overreliance on the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) for their due diligence.

Five of the thirteen companies—Bulgari, Cartier, Pandora, Signet, and Tiffany—have a code of conduct for their suppliers that they make public. In most cases, they include these policies in contracts with their suppliers. Eight companies have no such policies or do not make them publicly available. Boodles has pledged to enhance its existing code of conduct and make it public; Christ has pledged to make its existing supplier code of conduct public.

No company that Human Rights Watch contacted can trace all of their gold and diamonds back to their mines of origin, ensuring full chain of custody. One company, Tiffany, has achieved full chain of custody for gold by sourcing its newly mined gold from just one mine, the Bingham Canyon Mine in Utah.[131] Bulgari can trace its gold to two refiners that are certified under the RJC’s Chain-of-Custody Standard, but does not share information on mines of origin. Cartier and Chopard have chain of custody for a fraction of their gold supply. Cartier, for example, purchases the entire output of a “model mine” in Honduras.[132] The gold is fully traceable, and is refined in Italy at a facility that is solely dedicated to processing gold from the mine.[133] Some other companies—including Pandora and Christ—minimize risks of abuses in their gold supply chain by using almost exclusively recycled gold.

For diamonds, almost all companies require their suppliers to comply with the Kimberley Process, which should allow them to identify the country of origin of their diamonds, though the scheme suffers from a number of weaknesses. None of the companies can identify all of their diamonds’ individual mines of origin.

The OECD Due Diligence Guidance elaborates a detailed mineral supply chain due diligence framework for companies operating in or sourcing from conflict-affected or high-risk areas. The Guidance offers a broad definition of “high-risk areas” that focuses largely on the prevalence of serious human rights abuses or violations of international law.[134] This includes, among other things, a context characterized by the prevalence of hazardous child labor.[135] Under this framework, where companies cannot trace their material all the way back to the mine, they should require upstream suppliers such as gold refiners to provide them with detailed evidence that they have conducted due diligence in their supply chain.

Four companies examined—Bulgari, Pandora, Signet, and Tiffany and Co. —said that they require their suppliers to conduct self-assessments of human rights risks. But even these assessments were limited. Bulgari acknowledged that it is not requiring suppliers to disclose their gold full supply chain to them, but relies on their certification under the RJC’s Chain-of-Custody Standard. Signet and Pandora largely rely on RJC audits against the weaker Code of Practices to assure themselves that their suppliers have fully assessed risks.[136] As outlined above, the RJC process provides inadequate assurance of due diligence. Only a few companies conduct their own visits to suppliers to evaluate conditions.

Only a few of the companies examined took any apparent action to respond to risks in their supply chain. At least four companies—Bulgari, Pandora, Signet, and Tiffany and Co—have systems to work with suppliers to help them meet standards and take corrective action, as necessary.[137] Boodles has pledged to do so. Some jewelry companies state that they will sever contracts with suppliers that fail to meet standards, but it is difficult to appraise their willingness to do so in practice.[138]

The OECD Due Diligence Guidance requires independent third-party audits of suppliers’ due diligence. Ideally, this should include unannounced visits at mine sites by qualified monitors. More than half of the companies Human Rights Watch examined conducted no apparent third-party audits of their suppliers, either on their own, or through other entities like the RJC. Others, particularly Cartier and Signet, rely heavily on the RJC for such audits: They waive their own third-party audits for RJC-certified suppliers, delegating the task to the RJC.[139] In such cases, the companies’ own supplier codes of conduct—no matter how robust—may become irrelevant. In practice, companies rarely appear to use their own third-party auditors to assess their gold and diamond suppliers and almost none of the companies include visits to mines of origin as part of their third-party audits. The exceptions appear to be Tiffany, which conducts regular audits for all suppliers considered “high-risk” and regular audits of a sample of medium- and low-risk suppliers, and Pandora, which requires its suppliers to undergo audits for the RJC, but also independently audits some of its suppliers and visits mine sites where “red flags” have been identified.[140]

Jewelry companies should report annually on their human rights due diligence, including risks identified and steps taken to manage these risks. Only about half of the jewelry companies assessed report publicly on their sourcing of gold and diamonds.[141] Those that do typically include only general information on their sourcing policies and practices. Very few companies include any information at all about the results of their audits, areas of noncompliance, or steps that they are taking to address problems. One company that stands out is Pandora, which publishes an annual ethics report that includes an overview of noncompliance issues identified through its supplier audits.[142]

Publishing information about a company’s suppliers provides consumers and investors more meaningful information about the source of jewelry and watches and sends a message that companies are willing to be accountable when human rights abuses are found in their supply chain. However, none of the companies examined publish all the names of their gold and diamond suppliers. Some state that they do not do so to maintain competitive advantage. Several companies—such as Cartier, Chopard, Signet, and Tiffany—publish names of a few suppliers. For example, Signet publicly identifies De Beers, ALROSA, and Rio Tinto as suppliers of their rough diamonds.[143]

Finally, only a small number of companies evaluated source gold or diamonds from small-scale or artisanal mines, or support such mining initiatives. The Swiss jeweller Chopard, for example, sources a small proportion of its gold directly from artisanal mining cooperatives in Latin America that are certified against the Fairmined standard.[144] The company worked with the mines for three years to help them achieve Fairmined certification, providing them with financial support and expertise.[145] Cartier, as mentioned above, purchases the entire output of a “model” mine in Honduras that produces both industrially- and artisanally-mined gold. Cartier has also sourced gold from a Peruvian gold mine that has been certified against both the Fairtrade and Fairmined standards.[146] Several other companies, including Signet, Tiffany and Co., Cartier, and Harry Winston’s parent company, Swatch, have provided financial support to initiatives to develop responsible artisanal mines. Boodles, Pandora, Signet, and Tiffany and Co. state that they are exploring the possibility of sourcing from small-scale and artisanal mines in the future.[147]

Company Rankings on Responsible Sourcing

We assessed each company against the criteria for responsible sourcing outlined above, based on the information they provided directly, as well as information that is publicly available. Based on our analysis of each company’s performance, we ranked them as follows. A detailed assessment of each company appears in the next section, and a table providing an overview over the performance of all 13 companies can be found in the report annex.

Strong

Tiffany and Co. (US)

Tiffany and Co, founded in 1837, is a luxury jeweler with over 300 stores across 27 countries. Its 2016 revenue was approximately $4 billion, with jewelry representing 92 percent of its worldwide sales.[148] It is publicly traded.

Tiffany responded to Human Rights Watch’s request for information with a written, detailed letter and met with Human Rights Watch staff in person.

Tiffany and Co. states that it is “committed to reducing environmental impacts, respecting human rights and contributing in a positive way to the communities where we operate.”[149] Tiffany and Co. has full chain of custody over its gold; it purchases newly mined gold exclusively from a single mine that is identified publicly, and the remainder of its gold from recycled sources. Tiffany has partial chain of custody over its diamonds, and can trace some of its diamonds to specific mines. It does not publish the results of audits or how it responds to cases of noncompliance. On the basis of available information, Human Rights Watch considers Tiffany and Co. to have made strong efforts to ensure human rights due diligence.

Supply chain policy: Tiffany and Co. updated its Supplier Code of Conduct in 2016.[150] The Code of Conduct outlines expectations of suppliers regarding human rights, labor practices, environmental protection, and ethical business conduct, and asks suppliers to align with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Each supplier is expected to sign the Code, and the Code is part of the companies’ contracts. Diamond suppliers are expected to comply with the Kimberley Process and World Diamond Council System of Warranties.

Chain of custody: Tiffany and Co. has full chain of custody over its gold supply chain. Twenty-seven percent of its gold comes from a single mine in Utah, the Bingham Canyon Mine, and the remaining 73 percent comes from recycled sources.[151] It sources all of its recycled gold from one supplier, which has the ability to segregate gold from mined and from recycled sources. Its rough diamonds are sourced primarily from Botswana, Canada, Namibia, Russia, Sierra Leone, and South Africa.[152] Tiffany can trace some of its diamonds back to the mine of origin.

Assessment of human rights risks: All Tiffany and Co. suppliers are required to conduct a self-assessment based on the Supplier Code of Conduct. The company then assigns a low-, medium-, or high-risk rating based on the supplier’s self-assessment, the product category, past audits, and geographic location. Tiffany and Co. visits many suppliers on a regular basis; however, it does not visit mines of origin for diamonds. The company does not buy diamonds from Angola or Zimbabwe due to heightened human rights risks.[153]

Response to human rights risks: Tiffany and Co. says that it works with suppliers (including mines, refiners, polished diamond suppliers, and diamond polishing subcontractors) through a Social Accountability Program to review and improve their human rights, labor, and environmental performance. The company says it implements corrective action plans in cases where problems are found. If suppliers fail to meet the Suppliers’ Code of Conduct, the company may end contracts with those suppliers, and has done so in several instances.[154] Tiffany previously sourced from the Octea diamond mine in Sierra Leone, which has been associated with allegations of labor rights abuse and corruption; but informed Human Rights Watch that it stopped sourcing from Octea in March 2017.[155]

Third-party verification: Tiffany and Co. is certified against the RJC Code of Practices. Third-party audits are conducted regularly for all suppliers considered at high-risk to assess compliance with the Code of Conduct, and a targeted subset of suppliers. Audits address compliance with applicable laws, hours of work, wages and benefits, health and safety, freedom of association and collective bargaining, child labor, forced labor, harassment and abuse, disciplinary practices, discrimination, and environmental protection. Audits do not include visits to diamond mines of origin.[156]

Report annually: Tiffany and Co. publishes an annual sustainability report, which includes information on efforts to achieve responsible mining and ethical sourcing, and its approach to supplier audits. It does not provide any information regarding audits of suppliers, noncompliance information, or steps to address noncompliance.[157]

Publish suppliers: The source of Tiffany and Co.’s newly mined gold, Bingham Canyon Mine, owned by Rio Tinto, is public. It does not publish information on its other suppliers but shared the names of some suppliers with Human Rights Watch on a confidential basis.

Support for artisanal and small-scale mining: Tiffany and Co. has provided financial support for the Diamond Development Initiative and the Institute for Environment and Development to help formalize and promote responsible artisanal mining in both the diamond and gold sectors.[158] It does not source from artisanal mines but states that it is exploring the possibility of sourcing artisanally-mined metals that have been certified by third parties as responsibly managed, and hopes to begin such procurement soon.[159]

Moderate

Bulgari (Italy)

|

After publication of this report, Bulgari contacted Human Rights Watch and clarified that the company does maintain provenance of all its gold. This had been unclear from a prior response to Human Rights Watch. |

Bulgari is an Italian jeweler, owned by the French luxury group LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton S.E. (LMVH).[160] The company has about 200 stores worldwide.[161] LVMH’s jewelry companies had a total revenue of $3.4 billion in 2016; the revenue of individual companies is not made public.[162]

Bulgari responded to Human Rights Watch’s request for information with a detailed written letter and met with Human Rights Watch staff by conference call.

Bulgari is one of very few jewelry companies that has been certified under the RJC’s Chain-of-Custody Standard. However, Bulgari does not have chain of custody for its diamonds and does not require all suppliers to undertake human rights due diligence and third-party audits. On the basis of available information, Human Rights Watch considers Bulgari to have made moderate efforts to ensure human rights due diligence.[163]

Supply chain policy: Bulgari has a Code of Ethics that includes a brief statement requiring suppliers to respect labor rights; Bulgari also has a separate Anti-Slavery & Human Trafficking Statement.[164] Bulgari’s parent company, LVMH, has a more detailed Supplier’s Code of Conduct with provisions on labor rights and environment that also apply to Bulgari.[165] LVMH’s Code was under revision in late 2017 and Bulgari has informed Human Rights Watch that it will reviewing its Code of Ethics to reflect the changes. Respect for the codes is part of Bulgari’s contracts with its suppliers.[166] Diamond suppliers must be in compliance with the Kimberley Process and the World Diamond Council’s Standard of Warranties.[167]

Chain of custody: Bulgari sources gold only from refiners that are certified against the Chain-of-Custody Standard of the RJC.[168] As described above, the Chain-of-Custody Standard does not require comprehensive human rights due diligence and is mostly focused on a documentation of business transactions.[169] Bulgari informed Human Rights Watch in a letter that it uses transfer documents for each batch of gold purchased, which include information on the kind of material (such as mined or recycled) and the country of origin.[170] With regards to the diamond supply chain, Bulgari does not trace diamonds back to the countries or mines of origin.[172]

Assessment of human rights risks: Bulgari has put in place a Suppliers Risk Management Process to implement its Supplier’s Code of Conduct.[173] As part of this process, Bulgari requests suppliers to provide self-assessments on their social and environmental performance.[174] Bulgari uses this information to assess human rights risks, and to deploy auditors to conduct announced and unannounced visits to suppliers, such as its factories in Italy.[175] The risk assessment also includes visits approximately once a year to countries where Bulgari sources or is considering sourcing, and that are considered more high-risk. In October 2017, Bulgari stated that it intends to work with suppliers to reinforce and enlarge its due diligence processes, to ensure it applies to the whole supply chain, including on-the-ground mine assessments.[176]

Response to human rights risks: Bulgari states that, “We are aware that our business could have adverse impacts on human rights and local communities,” and that it is therefore committed to continuously assess and reduce these impacts.[177] When Bulgari finds that a supplier is not in compliance with its standards, the company says it usually gives the supplier between one and six months to correct the problem.[178]

Third-party verification: Bulgari is certified against the Code of Practices and the Chain-of-Custody Standard of the RJC.[179] Bulgari states that it conducts third-party audits of its suppliers.[180] All of its gold suppliers are certified against the RJC’s Chain-of-Custody standard, and its diamond suppliers are certified against the RJC’s Code of Practices.[181]

Report annually: Bulgari’s parent company LVMH publishes an annual report and a yearly environmental report, covering all LVMH brands.[182] The 2016 environmental report includes a section on Bulgari’s chain of custody for gold, and various environmental risks, but does not provide audit summaries, mention noncompliance issues, or steps to address noncompliance.