Introduction: Sanitation as a Human Right

“Nayla” (a pseudonym) was a 52-year-old teacher from Daraa, Syria, when anti-government protests began in March 2011. In 2012, she agreed to transport a military defector and was detained by government soldiers at a checkpoint. The soldiers shot at her car and beat her. They took her to a military building where she was held in solitary confinement and denied food and water for two days. She was transferred to another cell and detained for nearly seven months. When Nayla reflected on her detention and subsequent release, she said, “You feel you will never be free again – that you will never see your family, never go to [a proper] toilet. It is a joy just to go to the toilet when you want.”[1]

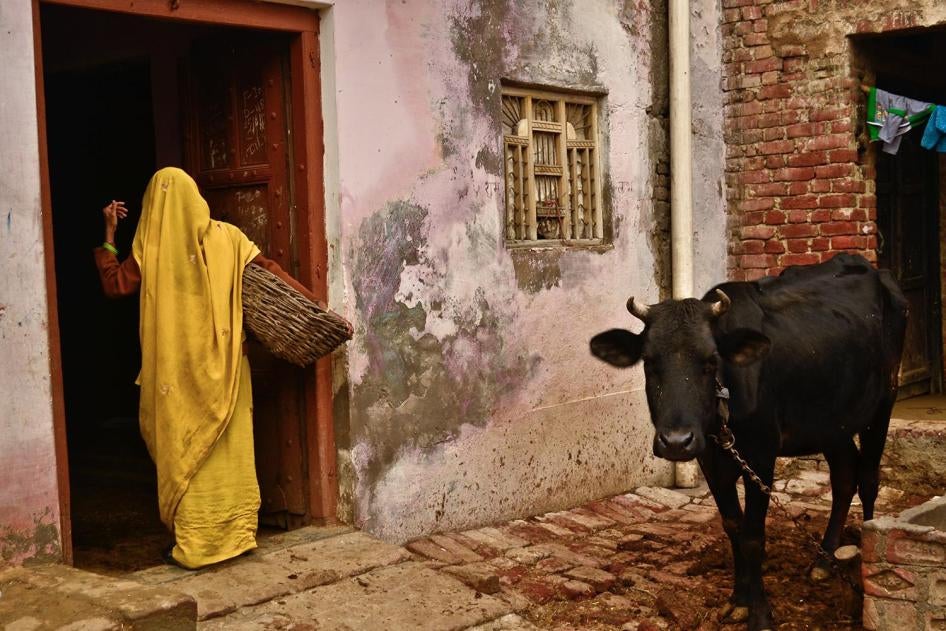

It is not surprising that in reflecting on the trauma she experienced over those seven months, Nayla associated her longing for a toilet with freedom. The manner in which a person is able to manage bodily functions of urination, defecation, and menstruation is at the core of human dignity. In her report on sanitation, the then-United Nations Special Rapporteur on the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation stated, “Sanitation, more than many other human rights issue, evokes the concept of human dignity.”[2] She continued, “Consider the vulnerability and shame that so many people experience every day when, again, they are forced to defecate in the open, in a bucket or in a plastic bag. It is the indignity of this situation that causes the embarrassment.”[3]

Lack of sanitation is a pervasive human rights concern globally that impacts other rights, including gender equality. While not an exact marker of the status of the right to sanitation, as of 2015, 2.4 billion people around the world are estimated to be using unimproved sanitation facilities, defined as those that do not hygienically separate human excreta from human contact.[4] Lack of sanitation is not only an affront to an individual’s dignity and rights, but endangers the rights to the highest attainable standard of health and to safe drinking water of other people because of the contaminating nature of human feces. Nearly a billion people practice open defecation—which has been linked to malnutrition, stunting, and increased diarrheal disease, among other negative impacts.[5]

Sanitation does not turn solely on the presence of a toilet or latrine.[6] It encompasses the entire system for the collection, transport, treatment, and disposal or reuse of human excreta and associated hygiene.[7] Breakdowns or barriers at any point within the system can lead to devastating impacts on people’s lives and rights.

Though not explicitly stated in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the right to sanitation is derived from the right to an adequate standard of living.[8] The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has reaffirmed that the right to sanitation is an essential component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and “integrally related, among other Covenant rights, to the right to health, … the right to housing, … as well as the right to water.”[9] According to UN General Assembly Resolution 70/169, the right to sanitation entitles everyone “to have physical and affordable access to sanitation, in all spheres of life, that is safe, hygienic, secure, and socially and culturally acceptable and that provides privacy and ensures dignity.”[10]

Despite the fundamental relationship between human dignity and the right to sanitation, national and international programs that address water and sanitation invariably invest more in water than in sanitation.[11] The UN Millennium Development Goal’s target (2000-2015) of halving the portion of those without access to safe drinking water—a concept not consistent with the definition of the human right to water—was formally met in 2010, yet progress on the sanitation target still lagged far behind. Billions of people are currently without access to improved sanitation.[12] Even where access has improved, large disparities exist between those who have access to sanitation and those who do not, with nearly half the world’s rural population lacking access.[13]

In development contexts, sanitation and water have long been linked as a congruent right, while the human rights community has interpreted them as distinct rights.[14]The UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted in September 2015, confirmed the separate but related nature of water and sanitation, calling for availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.[15] It includes independent targets for each, and provides a framework for monitoring and action related to sanitation. Though not defined consistently with the full definition of the right to sanitation, Target 6.2 calls for access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all by 2030 and for an end to open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations.[16]

A similar human rights interpretation of the separate but interrelated nature of the rights to water and sanitation has now been recognized by states in UN General Assembly Resolution 70/169, adopted in December 2015, which for the first time recognized the distinction between the human right to water and the human right to sanitation. By adopting the resolution, the General Assembly clarified that the rights to water and sanitation, while linked, are separate from one another and have distinct features, although remain part of the right to an adequate standard of living and are interrelated to other human rights.

As a distinct right, intimately related to the right to water (and other human rights, including the right to health) and similarly derived from the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to sanitation should be accorded the same level of importance as other components such as food and housing.

This report provides a factual foundation for understanding the distinct nature of the right to sanitation and denigration of human dignity related to its violation by describing contexts in which women, men, and children struggle to realize their right to sanitation. It draws from more than a decade of Human Rights Watch research that highlights the wide variety of abuses and obstacles people encounter in trying to perform the simple act of safely relieving themselves with dignity, including deliberate acts of abuse or discrimination. Although not an exhaustive review of the right to sanitation, this research shows that the deprivation of the right to sanitation can exacerbate multiple human rights violations.

This report looks at sanitation in:

- Schools

- Detention, Prisons, and Jails

- Immigration Detention Facilities, Migration and Displacement Camps and Centers

- Health Facilities and Residential Facilities for Persons with Disabilities

- Workplaces

- Households

Our key findings include:

- Many governments have not fully respected, protected, or fulfilled the right to sanitation in the context of public facilities, particularly in cases where people are deprived of their liberty and therefore, are completely reliant on the state for such services.

- In many contexts, women and girls and persons with disabilities face unique challenges, including difficulties in managing menstruation.

- Women, girls, and transgender persons sometimes face harassment or violence when there is no safe facility.

- Poor or no access to sanitation often occurs in the context of other human rights abuses and compounds their effects. For example, poor sanitation in the context of compulsory drug detention centers exacerbates the human rights impact of the arbitrary deprivation of liberty.

- Participation in public affairs is a key human rights principle, yet government failure to consult with communities, particularly marginalized minorities, and allow for meaningful participation in decision-making around sanitation may compound discrimination and exclusion in access.

- Government efforts to progressively realize the right to sanitation to the maximum of available resources may be undermined by gaps in accountability or corruption at the national or local level.

While this report does not document every sanitation-related human rights concern, it illustrates how the right to sanitation can be undermined in a variety of contexts through government action and inaction. It is intended to complement the research and analysis of the right to sanitation by the UN Special Rapporteur on the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation, and others.[17]

Our research shows that barriers to realizing the right to sanitation go beyond the availability of resources. Discrimination—based on caste, gender, disability, old age, or other protected status—may prevent some people from accessing adequate sanitation. Corruption or mismanagement may reduce the impact of government investments in sanitation. Authorities might not act to ensure that people in their care or custody can access facilities.

As states and donors work toward commitments made under Goal 6 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, more is needed than commitments to new resources. Instead, efforts toward meeting Goal 6 should include greater action to address the barriers to realizing the right to sanitation in all spheres of life. While this includes increasing resources—through budgets or development funding—it should be paired with a commitment to eliminate barriers to sanitation in those spheres under the control of government, to address discrimination, and to ensure human rights principles of accountability and participation undergird investments in sanitation.

The Right to Sanitation in Context: A Selection from Human Rights Watch Reporting

This section analyzes the right to sanitation by grouping examples from past Human Rights Watch reports into six different contexts:

- Schools

- Detention, Prisons, and Jails

- Immigration Detention Facilities, Migration and Displacement Camps and Centers

- Health Facilities and Residential Facilities for Persons with Disabilities

- Workplaces

- Households

The examples below are drawn from research from diverse country settings over a period of 12 years from 2005 until 2017, showing patterns of discrimination in access to sanitation, risk of violence, and lack of participation.

The descriptions of abuses, challenges, or violations related to the right to sanitation presented in this report are offered as illustrations of past occurrences, and not as current accounts of the facts. They aim to help develop a more complete understanding of the right to sanitation in context, and the types of problems that need to be addressed. This is not an exhaustive representation of the types of violations of the right to sanitation experienced around the world—the Special Rapporteur on the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation presented a more comprehensive account in 2014.[18]

Schools

There is a clear relationship between the right to sanitation and the right to education. Lack of clean water and sanitation can increase the risk for waterborne illnesses and diarrheal disease, and lessen the amount of time children are in school.[19] According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, 88 percent of deaths from diarrheal disease can be attributed to lack of clean water, sanitation, and hygiene.[20] Governments have the obligation to progressively realize the rights to water and sanitation in the context of schools to the maximum of their available resources. However, some students face barriers in accessing sanitation in school due to state action, inaction, or discrimination. Human Rights Watch has documented instances of barriers to sanitation in schools due to military or police occupation, destruction of facilities during armed conflict, and discrimination on the grounds of caste, refugee status, gender, disability, or gender identity.

Government action, inaction, and discrimination can create barriers to adequate sanitation in school settings that undermine several human rights and have devastating, and sometimes lifelong, consequences upon the educational opportunities of the most vulnerable students. The right to sanitation and education are interrelated and without access to adequate sanitation in schools, children will continue to miss out on valuable opportunities to attend class and learn.

Military or Police Occupation of Schools and Destruction of Facilities

Human Rights Watch research has found that even where governments have taken steps to invest in sanitation in schools, military or police occupation of a school can render these facilities inaccessible, particularly for girls. In India’s Bihar and Jharkhand states, Human Rights Watch found in 2009 that occupying police refused to let the students use sanitation facilities, even when the government had invested in such facilities, because the police wanted to use them exclusively.[21] This forced children to go to the toilet in more public spaces, causing anxiety and problems for some students, especially girls. A female student in Bihar told Human Rights Watch in 2009, “I generally go to a nearby field [to go to the toilet]…. I feel ashamed doing this.”[22] One 15-year-old girl, Lona, who studied at a high school that was occupied by police in Jharkhand in 2009, explained the impact this had on girls: “It becomes very difficult for a girl to stay in school for such a long time without a toilet. We are not allowed to go and use the toilet in the police camp.”[23]

In another instance, where toilets were destroyed by armed groups at Barwadih Primary School in Jharkhand, a teacher at the school explained in 2009 how difficult it was to be without a facility:

Particularly during the rainy season girl students face problems for going to the toilet because they have to walk to the open space for more than two kilometers. They find it difficult to meet this challenge.[24]

Discrimination Based on Caste

Some schools in India visited by Human Rights Watch in Dalit neighborhoods lacked toilets and clean drinking water common in schools located in non-Dalit neighborhoods.[25] In schools Human Rights Watch visited in 2014 that served both Dalit and non-Dalit children, some of the Dalit children told Human Rights Watch that teachers restricted their access to the toilet. A boy at one school told Human Rights Watch, “The Hindu boys are allowed to go to the toilet but we are not given permission.”[26] Vijay, 14, told Human Rights Watch he dropped out after being beaten for urinating after being refused permission to use the toilet: “The teacher didn’t let us go to the toilet. One day, I asked her for permission to go to the toilet but she said, ‘Sit down, go later.’ So I urinated outside the window and she hit me so hard with a stick that my hand broke. I went to the hospital to get my hand bandaged.”[27]

Discrimination Based on Refugee Status

Syrian refugee families living in Lebanon described to Human Rights Watch in 2015 and 2016 discrimination and the difficulties their children faced when trying to access sanitation facilities in public schools. Human Rights Watch interviewed families who reported that some teachers would not allow Syrian students to use the bathroom, or in some cases, the facilities at school were too dirty to use.[28] In one case, they described how staff locked bathrooms in the afternoon during the all-Syrian shift at one school.[29] Hedaya, 31, who had three children enrolled in public school, said, “They lock them for the second shift because they don’t want Syrians making them dirty. I spoke to the school teacher, but it solved nothing.”[30]

Children with Disabilities

Lack of accessible sanitation at school is a significant barrier to education for children with disabilities. Human Rights Watch found in Nepal in 2011 that some schools have no accessible toilets, so many of the children with disabilities who spoke with Human Rights Watch reported having to wait to go home to be able to go to the bathroom. Some had to call on their mothers to come from home every time they needed to use the restroom, so their mothers could assist them in the toilet.[31] One boy with a spinal cord injury in Pokhara told Human Rights Watch about his experience in a school without accessible toilet facilities: “My class is on the second floor. There’s a ramp [built by a local nongovernmental organization] but my friends have to help push me up. There’s no toilet that I can use so I have to go to the toilet at home and then wait until I come back from school.”[32] A 23-year-old woman with severe physical disabilities in South Africa described in 2014 similar challenges of having no ramps to access toilets: “I need to be carried everywhere … there were no ramps to go to the toilet. I wasn’t happy at school and wanted to move.”[33]

In 2013 Human Rights Watch found similar accessibility challenges for children with disabilities in China. For example, some schools require that parents take care of their children at school as a pre-condition of admitting the children. According to one disability rights activist, one school administrator said, “unless a parent accompanied the child, [they could not enroll the child] because…[t]he teacher cannot accompany the child to the bathroom, or do much else.”[34] In this case, a grandmother accompanied the child to school each day to take him to the bathroom.[35] A mother of a girl with cerebral palsy told Human Rights Watch that she also had to care for her child at school:

Their school has only one bathroom on the first floor [and her class is on the fourth floor]…. I bring her to school in the morning, and after two classes I go there again to help her to the bathroom, and again in the middle of the afternoon. I go back and forth many times.[36]

An educator in South Africa told Human Rights Watch in 2014 that her school, though intended for children with disabilities, cannot take students with special toilet needs.[37] One mother of a 10-year-old boy with spina bifida told Human Rights Watch that her son was out of school for over three years because schools could not accommodate his toilet requirements.[38] A mother of another boy with spina bifida told Human Rights Watch her son has had infections because school staff did not change his diapers regularly.[39]

Barriers to Girls’ Education

Girls in school may miss parts or all of school days due to lack of sanitation facilities that would allow them to manage their menstruation. Private and clean sanitation facilities are essential to ensuring girls can manage their hygiene during menstruation, without disruption to their education. Human Rights Watch spoke with girls in Haiti in 2014 who leave school to go home to wash and change the materials they use to manage their menstruation, because they cannot do that at school—leading some to miss as much as 30 minutes of instruction every time they need to change their materials.[40] Some teachers told Human Rights Watch that girls sometimes stay at home during menstruation because they have no option to manage their menstrual hygiene at school.[41]

In Nepal, Human Rights Watch spoke with women and girls in 2016 who described the difficulties of managing menstrual hygiene at school, and the consequences this had upon girls’ education. Chandni Rai, 19, said:

We had a toilet, but it was not good. If there are proper toilets, girls will feel better when they are on their periods and have to change their pads. Many girls stay home during their periods. They were marked absent and wouldn’t be able to learn. They couldn’t catch up because the course would have moved on. They would try to sit with their friends and catch up, but the teacher wouldn’t repeat [information]. Some of them left school because of this.[42]

In 2016 girls in Tanzania described the challenges they faced in managing their menstruation at school. Many girls told Human Rights Watch they use cloths that may leak or be difficult to keep hygienic because they cannot afford to buy sanitary pads, and sometimes miss school because adequate facilities to manage menstruation in school are not available. Rebeca, 17, said:

Sometimes [having your period] it’s a challenge and [it] stops girls from going to school. If you sit for too long, you can find that blood appears on your skirt. Boys laugh at you. We discuss this with friends. They can give you a sweater to cover your skirt; then you ask the teacher to let you go home.[43]

While the lack of a safe space to manage menstrual hygiene impacts all girls, the difficulty that girls with disabilities have in moving, dressing, and using the bathroom independently increases their vulnerability to intrusive personal care or abuse. Menstrual hygiene management and accessible sanitation facilities are particularly important in enabling girls with disabilities to continue their education.[44] Without such facilities, their education may be stopped abruptly when they begin menstruating. In Nepal, for example, Human Rights Watch found in 2011 that girls with disabilities often drop out of school once they reach puberty because there are no support services in school to help them during their periods.[45] One parent explained the difficult decision to keep her daughter home from school once she started menstruating:

When [my daughter] was 12, she started getting her periods. I would put the pad on her and she would take it out. She was also attracted to boys. I was scared that something could happen. Something sexual. There are no bolts on the doors. She got no sexual education. Neither do we know how to teach them nor did the teachers in her school. I decided not to send her to school.[46]

Transgender and Gender Non-conforming Students

Transgender students may face particular risks when using the toilet. Natasha, a 33-year-old trans woman in Malaysia, recalled to Human Rights Watch in 2014 the harassment she suffered in secondary school when using the toilet: “I went to the boys’ toilet but I was always disturbed there. The boys would prevent me from leaving the toilet. They would pinch me and touch me, and call me names.”[47] Transgender students in the United States interviewed by Human Rights Watch in 2015 and 2016 said that being made to use facilities that did not correspond to their gender identity made them feel unsafe at school and exposed them to verbal and physical assault.[48]

In addition to safety concerns, restricting access to bathroom facilities can negatively affect the physical and mental health of transgender and gender non-conforming students. Many transgender students interviewed throughout the US in 2015 and 2016 told us that when they lacked a safe or accessible bathroom in school, their standard strategy was to avoid all school bathrooms.[49] Sans N., a 15-year-old transgender boy in Utah, told Human Rights Watch: “I just don’t go to the bathroom at school. It’s just so awkward. I just look at the signs and I’m like, I can’t go in the ladies’ because it makes it me uncomfortable, and I can’t go in the boys’ because I’m going to get yelled at.”[50]

Research indicates that avoiding bathroom use for long periods of time is linked to several health complications, including dehydration, urinary tract infections, and kidney problems.[51] Cassidy R., a self-described agender 18-year-old in Utah, recalled: “I know a lot of my friends just didn’t go to the bathroom and suffered a lot of infections and health problems because of that.”[52]

The ability of transgender and gender non-conforming students to participate fully in the school community on an equal footing with their peers, and to learn, is also jeopardized when they are preoccupied with the lack of a safe space to relieve themselves and perform bodily functions in school.

Detention, Prisons, and Jails

Governments have a heightened obligation to ensure adequate sanitation for populations directly under their control, including civil and criminal detainees.[53] Yet, it is in detention that Human Rights Watch has found some of the most startling deprivations of this right. While some violations of the right to sanitation are due to a failure to ensure an adequate standard of living for imprisoned populations, other violations arise when sanitation is used in a manner to abuse, torture, and degrade prisoners and detainees.

Although the right to sanitation for imprisoned populations may arise due to a lack of adequate and hygienic sanitation facilities, it is also denied as a humiliating and degrading form of punishment, torture, and abuse. Government action is necessary to ensure not only that prisons and jails have safe and adequate sanitation facilities, but that all prisoners are able to regularly utilize the facilities and manage their hygiene without fear.

Omission of the Duty to Ensure an Adequate Standard of Living

Many prisons and jails do not have adequate resources for the number of detainees they house—leading to deplorable conditions. In Uganda, street children detained by police as “criminals” described to Human Rights Watch in 2013 and 2014 the limited access to toilets in detention. One 8-year-old child, detained with adults in a police cell for five days, told Human Rights Watch: “There was nothing to sleep on but urine in the floor. We used a bucket to defecate in and urinate in, and there was overflow on the floor.”[54] Likewise, an inmate in a Zambian prison noted in 2009 that the two toilets reserved for 150 detainees “were always overflowing as people have diarrhea all the time.”[55]

In Haiti, Human Rights Watch found similar conditions in a prison in St. Marc in 2012 where 36 prisoners occupied a cell designed for 8.[56] Prisoners relied on buckets in the cell to contain their excreta, leading to an unbearable stench in the cells. In 2012, the UN in Haiti marked an increase in inmate deaths related to a resurgence of cholera in the unhygienic prisons.[57] In Kenya, inmates arbitrarily detained without charge told Human Rights Watch that the buckets that served as toilets inside their cells were only emptied when full.[58] Some of these inmates had contracted diarrhea while in detention that they believe to be related to the conditions of detention.[59]

In some facilities, the lack of toilets may open up detainees to further abuse. For example, in Sri Lanka, Human Rights Watch found in 2011 and 2012 that poor conditions in camps set up by Sri Lankan security forces to detain ethnic Tamils led some detainees to defecate in plastic bags or in their detention rooms, which lacked toilet facilities. One detainee told Human Rights Watch: “There was no toilet so I had to defecate in the room. They would beat me for this but would not take me to a toilet.”[60] Female prisoners in Zambia reported similar concerns in 2009: “If we excrete for any reason [in the cell]… we were told we would be punished by the cell captain—we must get permission from cell captain to poop when necessary.”[61]

Women detainees may be further impacted by poor sanitation if they are not provided with the materials and privacy needed to manage their menstruation. The revised UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Mandela Rules) provide that “sanitary installations shall be adequate to enable every prisoner to comply with the needs of nature when necessary and in a clean and decent manner,”[62] and that prisoners “shall be provided with water and with such toilet articles as are necessary for health and cleanliness.”[63] Despite this standard, women are not always provided with materials to manage menstruation while in prison. In Zambia, for example, an inmate named Catherine, 38, told Human Rights Watch in 2009, “The prison does not provide us with soap, toothpaste, or sanitary pads. If others don’t bring them for us, we have nothing.”[64] Instead, she said detainees in the facility must rely on family members, church donations, or exchange sex or labor to obtain sanitary pads and other essential hygiene products.[65]

Human Rights Watch found that detainees or prisoners with disabilities may experience even more challenges than the majority of the detainee population. For example, in Zambia, Chrispine, a 46-year-old detainee with an amputated leg, told Human Rights Watch in 2009, “I find it difficult to balance, jumping over my colleagues in the cell to the toilet.”[66]

In prisons throughout the United States, Human Rights Watch found that mobility-impaired older inmates often confront a shortage of wheelchair-accessible bathrooms, including showers with seats, bars, and no shower lip to step over; and too few rooms on a first floor so they are not required to climb stairs.[67]

The conditions in drug treatment or compulsory drug detention centers can also be very poor. In Russia, for example, in 2007 Human Rights Watch spoke with a drug user from Kazan who had been in a detoxification clinic. “The toilet was horrible,” he said. In addition, in 2007, drug users told Human Rights Watch that the inpatient clinic in Penza only had one bathroom for all patients, both men and women. Furthermore, the bathroom also served as a smoking room. A woman who had been in the facility told Human Rights Watch that when she went to the bathroom at the facility, she would have to ask a group of smoking men to turn around and look the other way so she could use the toilet.[68]

Pueksapa, who was held at the Somsanga drug detention center in Laos for nine months, told Human Rights Watch in 2010 that “there was not enough water for the showers, only a few minutes to shower every day.”[69]

At a drug detention facility in Vietnam, a detainee who had spent a month in solitary confinement told Human Rights Watch in 2010: “It was bad. There was no water in the toilet or for showering or feminine hygiene.”[70]

Violations of the Right to Sanitation arising from Abuse, Torture, and Degrading Treatment

In some prisons and jails where adequate sanitation facilities do exist, authorities may use toilets as a form of punishment to abuse and torture prisoners. Prisons or jails may have hygienic toilets, but authorities may limit detainees’ access to them, causing both emotional stress and potentially physical discomfort. Human Rights Watch research in a Belarusian detention facility in 2011 revealed some of the physical impacts of detainees’ coping mechanisms for poor access to sanitation. In a detention facility in Minsk, prisoners were only allowed access to a toilet twice a day.[71] One young female detainee told Human Rights Watch, “They took us to use a toilet twice a day which really wasn’t enough for me. I stopped drinking fluids because I could not wait between the toilet breaks. I started having serious health problems as a result.”[72] The detention facility doctor subsequently examined her and requested she have more regular access to the toilets, which was granted.

Prison officials sometimes use the lack of proper waste management in a facility as additional punishment for prisoners. For example, in Cote d’Ivoire, a man who had been detained at a military police camp told Human Rights Watch in 2012:

One of the cells was for people to piss and shit. It was the only room with a hole for a toilet, but there were so many of us that soon the whole room was just covered with urine and shit. One day, I guess [the soldiers who interrogated me] decided they didn’t like my answers. […] [T]hey put me in the toilet room; there were a couple other people in their already. The smell was horrible, and I had open wounds from being beaten. You couldn’t sit anywhere without being in [excrement]… They did this to people every day, […]. If they weren’t happy with your answers, or thought you were acting up, they threw you in the shit room for hours, sometimes at night…. By the time I was released, I’d developed these skin infections [seen by Human Rights Watch, though the cause could not be confirmed] on my arm and leg.[73]

Detainees themselves may be charged with cleaning toilets in prisons and jails. One inmate in a prison in Zambia said in 2009 that “the remandees are told to pick up the toilet tissues after the night and clean up the area in the cell. This is without gloves, it spreads diseases. There was a cholera outbreak a while back in cell three, [which made] 15 inmates [sick].”[74]

In 2010, interviewees who had recently been detained at Somsanga Treatment and Rehabilitation Center in Lao described staff ordering the punishment of individuals who had infringed center rules in ways that constituted inhuman and degrading treatment. In addition to being beaten by fellow detainees, Paet, a detainee, said:

They sent us to the septic tank. We had to take the shit to the main garbage place. Then we had to clean the shit out of the septic tank with water. It was disgusting. Some were vomiting and others were dizzy. We had to stand in the shit. There were worms in it.[75]

Human Rights Watch has also documented how detention officials sometimes restrict toilet usage as an interrogation tool. For example, L.V., a detainee in an Ethiopian prison, told Human Rights watch in 2013 that his access to the toilet was linked to interrogation methods in the prison. L.V. told Human Rights Watch that when he first arrived, he was only allowed to use the toilet once a day. After two or three months, guards permitted him access to the toilet twice a day. According to L.V., “They investigate, investigate, punish, they want to get something, and either they get some evidence or they don’t and then they start showing kindness.”[76] L.V. also reported being handcuffed for five months. He told Human Rights Watch that among other difficulties, “It was also very difficult to remove my trousers when I went to the toilet.”[77]

In some cases, Human Rights Watch has documented toilets as a tool of torture or abuse. A man detained by the Sri Lankan military in 2006 was held in a toilet for 28 days, during which he was tortured every day. He told Human Rights Watch that the torture escalated and that on one occasion, “they hung me upside down with my head touching the used toilet bowl and threatened me that they would make me eat my feces.”[78] In China, Human Rights Watch spoke with a former detainee in 2014 who reported that detainees were forced to stand on dirty toilets.[79] Other detainees in China reported to Human Rights Watch that the use of restraints prevented detainees from being physically capable of using the toilet: “Two different inmates were chained to the floor for two weeks, which meant they were unable to go to the toilet, another inmate would bring them a bucket.”[80]

Perversely, the privacy from intrusive security cameras afforded by some toilet facilities in detention has made some prisoners more vulnerable to abuse by prison officials. A man who suffered severe abuse in a prison in Bahrain in 2015 reported to Human Rights Watch that riot police officers beat him and two other inmates in the room that had sanitation facilities because there was no camera there.[81]

Limited access to toilets can also make inmates more susceptible to beatings as a form of punishment. At Gikondo Transit Center, an unofficial detention center in the Gikondo residential suburb of Kigali, Rwanda, Human Rights Watch found in 2014 that female detainees with young children or babies were particularly vulnerable as they were frequently beaten when a small child or baby defecated on the floor. A female detainee explained how she was beaten because her ill daughter was not allowed to use the toilet and ended up defecating on the floor:

My child had a bad stomach and she could not leave the room to use the toilet. If a child [defecates] in the room, they hit the mother. The “counselor” [prison boss] does it. My daughter needed to use the toilet and I tried to open the door, but the counselor refused. Since my child was in pain, I decided I would rather be beaten so she could use the toilet.[82]

Restricted access to toilets or those that lack privacy may open up detainees to risks of sexual assault or abuse. When Uzbek police arrested Elena Urlaeva, a leading human rights defender in Uzbekistan, in 2015, they sexually violated her, conducting a vaginal and rectal cavity search that caused her to bleed.[83] They then restricted access to the toilet, and sexually harassed her when she did try to relieve herself. She said:

I needed to use the toilet but they would not allow me and so I asked for a bucket but they said “You’ll go outside and we will film you bitch and if you complain about us then we’ll post the video of your naked ass on the internet.” I couldn’t stand it any longer and was forced to relieve myself outside in the presence of police officers who filmed me.[84]

According to Urlaeva, she had “never experienced such humiliation in [her] life.” [85]

Migration and Displacement Camps and Centers, Immigration

Detention Facilities

International law ensures the rights to water and sanitation for persons fleeing persecution, conflict or disaster, migrating for work, or being displaced for other reasons.[86] However, Human Rights Watch research has found that it is difficult for many refugees, migrants, or internally displaced people to realize these rights, particularly in the context of camps or detention facilities. Sanitation systems in camps for refugees, displaced persons, asylum seekers, and migrants are often inadequate.

Migration and Displacement Camps and Centers

Human Rights Watch found in 2012 that ethnic Kachin refugees from Burma in China’s Yunnan Province faced serious health concerns from lack of sanitation facilities. Refugees were often forced to urinate or defecate in holes in the ground. The head of a camp that had one such hole for 300 refugees told Human Rights Watch, “We dug one toilet hole with four stalls for the whole camp, and now the hole is full, so it smells very bad.”[87]

Migrants and asylum seekers in makeshift camps in Calais, France, which Human Rights Watch visited in 2015, had no access to sanitation, and very limited access to running water.[88] Zeinab, a 23-year-old woman from Ethiopia living with her husband in the largest camp, told Human Rights Watch that she washed outside with a plastic sheet around her. “More than food, not having a bathroom is a bigger problem,” she said.[89] The camps were dismantled in October 2016.

Asylum seekers and migrants at three reception centers on Samos, Lesbos, and Chios in the Greek islands, known as “hotspots” for refugees fleeing conflicts in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa, described unsanitary and overcrowded conditions in the centers when Human Rights Watch visited in May 2016. A 27-year-old Palestinian Syrian man in the Moria camp said, “The toilets are always dirty and flooded. They never clean them.”[90] A Syrian woman, 20, at the VIAL detention facility said:

There are only three toilets for women, not three bathrooms, but three toilets. We have to line up for two hours to use the bathroom. We are not given any soap. There is no soap dispenser in the bathroom. The water is ice cold when it is available at all.[91]

The lack of proper sanitation facilities posed serious health risks for people displaced by conflict in 2008 in Sri Lanka’s Vanni region. A humanitarian worker told Human Rights Watch, “When someone is displaced, they don’t bring their toilet with them.”[92] Health authorities raised concerns that lack of properly constructed latrines led to widespread open defecation, which could contribute to possible outbreaks of waterborne diseases and increase risks of sexual and gender-based violence for women forced to relieve themselves outdoors. A hospital in the region also reported unusually high numbers of snake bites since the government had compelled the humanitarian community to withdraw from providing services to the displaced: 194 snake bite patients in one month alone, including 2 fatal attacks. Most of these snake bites were reportedly due to the widespread open defecation caused by the lack of sanitation facilities.[93] Anxiety about snake or animal bites has been associated with open defecation in other parts of the world as well.[94]

Women and girls living in displacement camps in India told Human Rights Watch a year after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami that they did not have proper, safe, and private sanitation or bathing facilities. One woman pointed to some shrubs behind the shelter and said that is what she and her daughters used as a toilet.[95] Likewise, in Haiti after the earthquake in 2010, Human Rights Watch found that in the displacement camps, women and girls reported insufficient and unsafe sanitation facilities. Many complained of having terrible vaginal infections and were not able to manage their personal hygiene, particularly during menstruation.[96]

One Haitian woman recounted the fear she and other women experienced when trying to reach portable camp toilets in a distant, insecure area. “We are scared,” she said. “We have no security.”[97] Because of that, she sometimes avoided the camp toilets and instead defecated and changed menstrual materials in the open. As a result, she said that she chose the safety of staying near her tent over using the minimal sanitary facilities in the camps, even if that could contribute to vaginal infections.

Human Rights Watch received reports that in some temporary shelters in India a year after the 2004 tsunami, women and girls had resorted to walking in pairs to and from community toilet and bathing facilities to ward off harassment from men.[98] Likewise, women and girls in displacement camps in Haiti in 2010 and 2011 told Human Rights Watch about constant harassment they faced without secure bathing facilities. They described being pinched, poked, or leered at by boys and men in the displacement camps when they washed themselves out in the open, because there was no safe and private place to bathe.[99]

Women at “hotspot” centers in Greece in 2016 also described being sexually harassed routinely, especially when going to and from or using the camp sanitation facilities. A 23-year-old Syrian woman, who was alone with her three small children at the Moria camp, said that she did not go to the toilet at night because drunk men hang around the women’s latrine and had grabbed her hand and touched her shoulder in ways that made her feel uncomfortable.[100] Women also described a lack of privacy when using the showers. A 27-year-old Afghan widow with three children at the VIAL detention facility said, “The situation is very bad in the women’s showers. The showers don’t have curtains but you don’t have another choice. If other women are with me I feel comfortable.”[101]

In 2011 and 2012 Human Rights Watch found similar concerns about the absence of privacy in displacement camps in Sri Lanka. Soldiers and police would infringe on the privacy of women by watching them when they bathed or used the toilet.[102] Human Rights Watch uncovered one case in which this harassment resulted in sexual violence. A 28-year-old woman said, “One evening when I was returning after a bath with some others, suddenly a group of soldiers appeared. Some of the girls managed to scream and run away. I was raped.”[103]

Persons with disabilities and older people may have even greater challenges in accessing sanitation in camps, especially when camp layout and terrain makes it difficult to move around. Even when camp sanitation facilities are constructed to be accessible for persons with disabilities and older people, uneven, rocky terrain and long distances to facilities may prevent persons with disabilities from using them, as Human Rights Watch found in camps in Greece in 2016 and 2017.[104] Fifteen asylum seekers and migrants with disabilitiesin Greece said that they or their family members were not able to use toilets and other hygiene facilities because they were not accessible.[105]

Older people with disabilities can face particular risks if access to sanitation is obstructed. Older men and women, in particular, face higher risks of urinary tract infections, that can be further aggravated by holding urine until support is available.[106] In 2016 in the Cherso refugee camp in Thessaloniki, Greece, Human Rights Watch came across Naima, a 70-year-old refugee woman from Aleppo, Syria. Because she had diabetes and used a wheelchair, she had difficulty accessing the toilet and wash area. Her daughter, Hasne, said:

It is very difficult to take my mother to the toilet. She crawls from the tent to the wheelchair – she can’t take one step. I put her in the wheelchair, I fill the bag with bottles that I use to help her wash her hands and take ablutions [the Islamic practice of washing before prayer] because she can’t reach the existing taps in camps from the wheelchair nor can she stand up.[107]

In 2015 Human Rights Watch found in displaced persons camps in the Central African Republic that accessing latrines can be difficult as some are not fully accessible and often persons with physical disabilities have to crawl on the ground to enter. Jean, a man with a physical disability living in M’Poko camp, said:

My tricycle doesn’t fit inside the toilet so I have to get down on all fours and crawl. Initially I had gloves for my hands so I didn’t get any [feces] on them but now I have to use leaves.[108]

Detention Facilities

Migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers detained by authorities face many of the same challenges as detainees in prisons or jails. In addition to adults, unaccompanied children or families with children are often detained in abysmal conditions. A mother detained in Indonesia with her infant son in 2012 said, “When it rains and the water levels get high, the sewage comes up out of the toilets. It stays in the room. It’s very dirty. There are insects in the water anyway, but this is even dirtier.”[109]

Immigrants, including children, detained in Thailand described untenable long-term detention conditions. In 2013, one mother described conditions that she and her four daughters had experienced in detention—where there were only three toilets for approximately 100 detained migrants. Her teenage daughter would avoid using the toilets because they had no doors or privacy.[110] Another immigration detainee in Thailand, an American man, said that one of the two toilets available in his cell, occupied by around 80 people, was permanently clogged, so “someone had drilled a hole in the side—what would have gone down just drained onto the floor.”[111] He also described using the same fetid water to wash dishes after mealtimes:

After every meal you’d have to go into the bathroom to use the water and sponges there to clean your tray. If someone was in that toilet, there’d be shit in the water you’d wash your tray in… The sponges were on the floor, in the shit. That was the only way the trays were washed.[112]

An 8-year-old girl told Human Rights Watch, “The toilet was really bad, the smell was really bad.”[113] Even an immigration officer raised concerns about the toilet facilities, highlighting specifically his concern for girls: “The toilet needs to be improved, the cleaning. I see that it’s not really comfortable when they need to clean themselves. … I’m concerned for the girls, no privacy to wash.”[114]

Asylum seekers in Bulgaria faced similarly harsh conditions, in addition to physical abuse. The toilets in facilities were very dirty and inaccessible at night, and were usually insufficient for the number of detainees.[115] A Syrian man, 33, held at a Bulgarian border police detention facility in 2013, told Human Rights Watch about the conditions:

I told the police … I wanted to use the toilet. The guard said no, he would not let me use the toilet. After that I walked some distance outside the building to urinate, but the guard saw me and used his taser on me. He shocked me with it twice. First, when I was urinating and then to make me move faster.[116]

A 35-year-old Afghan mother of three children who, with her family, spent eight days in a “cage camp” for asylum seekers reported in 2013 witnessing guards use electric shock on people when they asked to go to the toilet.[117] Likewise, migrant workers who were detained as part of a mass expulsion from Saudi Arabia in 2013 told Human Rights Watch that there were vastly insufficient sanitation facilities for migrants at the detention facilities. One man said, “There were two toilets for 1,200 people, including dozens of children.”[118] Nur, a 24-year-old man from Mogadishu, Somalia, described the conditions he had experienced during his detention at a deportation center in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: “There was no air conditioning, it was very hot. There were five toilets for all of us [just under 790 people].”[119]

In 2016 Human Rights Watch interviewed unaccompanied asylum-seeking and migrant children at the Mygdonia Border Guard Station in Thessaloniki, Greece, who said a broken shower drain was causing water to flood into the cell, where they slept on mattresses on the floor. Children said they used their own clothes to block the water.[120]

Poor sanitation facilities available to migrants, displaced people, or refugees can compound their health risks. For example, in an immigration detention facility in Greece, sewage was running on the floors when Human Rights Watch visited in 2011.[121] The guards told Human Rights Watch that the prisoners had broken the toilets to protest the conditions. The smell was so strong that guards wore surgical masks when they entered that area. A 14-year-old Afghan boy detained in the facility said, “The toilet is broken. The sewage comes out. There's a very bad smell. If a person comes here, 100 percent he will get sick.”[122]

Migrant and refugee women and girls in detention may experience additional difficulties in managing their menstruation. Women in several immigration detention facilities in the United States described arbitrary and humiliating limitations on access to sanitary pads. US government standards state that facilities will issue feminine-hygiene items on an as-needed basis. However, a number of women told Human Rights Watch in 2008 that officers would distribute a certain quantity of pads (two to six), and obtaining more “as needed” posed a challenge. Nadine recalled:

I needed three pads. It would just gush. It would end up soaking my clothes. If my clothing got soaked, I could go through a shift change without a change of clothing. ... We were shaken down every night. If you had hoarded they would take [away] the extra pads.[123]

Another woman, Elisa, said that the immigration detention facility she was in refused to give her more than two pads. “I had to just sit on the toilet for hours because I had nothing else [I could] do,” she said.[124] Nana, a woman at a detention facility in Arizona, described similar conditions:

They only give two pads. In the morning they come and give you two. If you need more than that you have to go to the nurse. “Why do you need more pads?” You have to tell her, “Because I bleed so much.” But it has to be an extraordinary reason. If it’s normal for you to have a heavy period—nothing. I bleed through three pairs of pants.[125]

An Afghan woman detained with her three children, ages 8 to 12, at a temporary holding facility in Ukraine told Human Rights Watch in 2009, “The border guards in Luts’k didn’t give sanitary pads. I used toilet papers; it wasn’t sufficient. I was one month without showering.”[126]

Risk of Harassment and Abuse

As with prisons, governments have heightened obligations to ensure that bathrooms in detention facilities are safe, yet they are often the site of sexual violence and harassment. For example, in 2005, immigration detainees at a facility in the United Stated reported that guards used a camera phone to take pictures of women detainees leaving the shower and the bathroom, and also while they were sleeping.[127] A 17-year-old Somali girl seeking asylum and detained in Ukraine reported in 2010 similar harassment, but by other detainees: “The boys and girls are in one place. … They [boys] tried to spy on me in the shower. There were up to six girls and 30 to 40 boys. We didn’t go to the toilet freely. They stood and smoked and we were scared. … I was afraid repeatedly.”[128]

A Somali refugee, 17, detained in 2008 at a Kenyan police station inside the refugee camps at Dadaab told Human Rights Watch that, after eight days of detention, police raped her when she left her cell to use the toilet: “I left the cell to go to the toilet but two policemen stopped me and told me to go into a room and lie down. One of the men held down my arms and the other raped me.”[129]

Accessing sanitation facilities in detention can also heighten the risk of harassment and abuse for transgender and gender non-conforming individuals, especially when privacy to use showers and toilets is lacking and facilities are overcrowded. In 2015, Human Rights Watch interviewed Talia, a transgender woman from Mexico being held in a US immigration detention facility in the state of Texas. Talia said a male detainee groped her buttocks and demanded oral sex during shower time, which she had to share with approximately 150 male detainees. After Talia reported the incident, she said a male guard escorted her to the restrooms so that she could shower at another time but that he would himself stare at her while she changed her clothes:

The guard stares at my breasts. I asked him to open the laundry room for me so that I can change my underwear and he said, “No.” I talked to the [ICE] supervisor and he told me I could change in the passageway in the bathroom, but there are men there. How can I change there? I might as well just change in my bed.[130]

Health Facilities and Residential Facilities for Persons with Disabilities

Residential facilities for persons with disabilities and health facilities often lack adequate sanitation facilities. Abusive practices in these institutions may make using or accessing the bathroom difficult. In psychiatric wards in Ghana in 2011, for example, Human Rights Watch researchers saw toilets filled with feces and cockroaches. From the gates of these wards, there was a powerful stench of urine and feces.[131] A 21-year-old man chained to a wall in one of these facilities told Human Rights Watch, “We shit here and they don’t come to clean up. … It smells a lot inside here.”[132] In another facility Human Rights Watch visited in Ghana, most persons with psychosocial disabilities were chained to trees, and they had to urinate in the open and defecate into small plastic bags which were later thrown into surrounding vegetation.[133] In so-called prayer camps visited by Human Rights Watch that also housed persons with psychosocial disabilities in an effort to “heal” them by prayer, many of the patients were also chained with only about two meters of chain for movement. People had to bathe, defecate, urinate, manage their menstrual hygiene, eat, and sleep in the spot where they were chained.[134]

At a hospital in India for women with psychosocial disabilities, a hospital superintendent told Human Rights Watch in 2013 that, with just 25 working toilets for more than 1,850 patients, “[o]pen defecation is the norm.”[135] In a setting where people are not always in control of their bowel movements, a lack of adequate toilets is especially distressing and poses a serious health risk, compounded by the fact that many women and girls in the hospital walk around barefoot.[136]

Human Rights Watch research in institutions for children with disabilities in Russia in 2012 and 2013 raised particular concerns. In one state-run facility, a volunteer staffer told Human Rights Watch:

The children [in the specialized state institution] don’t drink much. They get their diapers changed three times per day, but the staff can’t give them more diapers. So they limit the amount of water the children drink.[137]

In hospitals providing care to maternity patients, Human Rights Watch has found non-functional and unhygienic toilets in maternity and surgery recovery wards. In Kenya in 2010, for example, women recovering from fistula operations in a district hospital maternity ward said there were several toilets some distance away from the ward, but none could flush and some were overflowing with feces.[138]

Sometimes district hospitals had to absorb extra maternity patients because health facilities in more rural areas had no water and could not perform deliveries without it. Research carried out by WHO and UNICEF on healthcare facilities in 54 low and middle-income countries, representing 66,101 facilities, found that 19 percent did not have improved sanitation and 35 percent lacked soap and water for washing hands.[139] Such a lack of essential water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services in healthcare facilities led to serious consequences, including the spread of infections and even discouraging women from going to these healthcare facilities to give birth.[140]

Misuse of funds intended for health facilities may also lead to breakdowns in systems at an institutional level. For example, in 2007, Human Rights Watch looked at some of the human rights impacts—particularly on basic health care and primary education—of local government mismanagement and corruption in Nigeria’s oil-rich Rivers State. According to a high-ranking state official, out of the 30 health centers in the local government area, no more than two or three had any sort of toilet facilities, even pit latrines.[141] Human Rights Watch spoke to a health facility staff member who described the challenges they face due to a lack of resources: “We are lacking many things. We have beds but no mattresses[…]. We have no toilet; patients will use the toilets of the people who live nearby to here.”[142]

Workplaces

Adequate water and sanitation facilities in employment are necessary components of the right to safe and healthy working conditions.[143] Without access to safe drinking water, adequate sanitation facilities, and materials and information necessary to promote good hygiene, the right to health and safety at work cannot be fulfilled. The right to sanitation at the workplace is reflected in UN Resolution 70/169, which affirms that “the human right to sanitation entitles everyone, without discrimination, to have physical and affordable access to sanitation, in all spheres of life.”[144]

Harsh working conditions, long hours without breaks, or excessively high production quotas can make toilets inaccessible to workers, particularly in factories. Garment factory workers in Cambodia described to Human Rights Watch in 2013 the challenge of not being able to access the toilet when working long shifts.[145] Keu, a garment worker in Phnom Penh, said, “I sit for 11 hours and feel like my buttocks are on fire. We can’t go to the toilet.”[146] Cheng Thai, from a different factory, confirmed a similar experience: “We have to sit and work till we finish the quota. …They don’t allow the workers to take a break.…We cannot use the toilet even if we have diarrhea if we don’t get a toilet pass.”[147]

Garment workers in Bangladesh reported similar constraints in using the toilet facilities at their workplace. Workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch in 2013 said that they were verbally abused for using the toilet and thus avoided the toilet, as well as drinking anything during the day.[148] Sometimes this verbal abuse also had sexual overtones. One woman told Human Rights Watch, “We were not allowed to spend sufficient time in the toilet. If someone stays a long time in the toilet they use foul language like, ‘Did you go to toilet to make love?’”[149]

Agricultural workers are another class of workers that face difficulties in accessing sanitation. In the United States, for example, Human Rights Watch found in 2009 and 2010 that child agricultural laborers often do not have access to sufficient drinking water, and suitable handwashing facilities or toilets—potentially contributing to urinary tract infections, increased exposure to pesticides, and gastrointestinal disorders.[150] Tobacco workers risked nicotine poisoning.[151] One mother described the impact of not having portable toilets near the field where she and her 10-year-old son worked: “[He] had diarrhea one day behind the wheel [of the car] and we forgot toilet paper. He was trying to hide behind the wheel of the car.” [152]

Likewise, without access to toilets, most children Human Rights Watch interviewed who worked in tobacco fields in the United States said that they would relieve themselves in wooded areas near their worksite or refrain from relieving themselves at all during the day—aided by avoiding drinking liquids, which increased their risk of dehydration and heat illness. A 17-year-old girl, who had worked on tobacco farms in North Carolina since age 12, said, “If you have to go, there’s the woods. … First time I was out in the field, I told my mom I have to go pee. And my mom was like, ‘You have to go in the woods.’ But I was scared. I didn’t want to. My mom said, ‘You can’t go all day like that.’ I said, ‘What if a snake comes out?’”[153] Another 16-year-old girl worker in North Carolina explained, “You’d have to just get yourself somewhere to go to the bathroom. To the trees, or just try to get away from the others working, have someone else help cover you up.”[154]

Farmworkers in South Africa reported to Human Rights Watch in 2010 that farmers often do not provide toilets near fields, forcing farmworkers to relieve themselves in or near the vineyard or orchard where they work. A seasonal farmworker said, “When working in the field, there is no toilet near the field. So dig a hole and help yourself.”[155]

Human Rights Watch found that in situations where workers stay in employer-provided housing, the sanitation facilities may be inadequate. Thai farmworkers in Israel went on strike in 2013 to protest poor living conditions, including lack of functioning toilets and showers.[156]

Similarly, migrant construction workers in Beijing told Human Rights Watch in 2007 that the toilets and washing facilities on-site were severely inadequate and, in some cases, dangerously unhygienic. Many lacked running water.[157]

Lack of gender segregated and safe toilets can be a barrier to women’s employment. In Afghanistan, a senior police administrator acknowledged to Human Rights Watch in 2012 that the lack of safe toilets and changing facilities might be barriers to women joining the police force—which in turn had a significant impact on how police respond to crimes against women and girls.[158]

An international advisor working closely with female Afghan police officers told Human Rights Watch that “[t]oilets are a site of harassment.”[159] Unsafe toilets and changing areas opened Afghan police women up to sexual harassment and assault. According to the advisor, “Those facilities that women do have access to often have peepholes or doors which don’t lock. Women have to go [to the toilets] in pairs.”[160]

Lack of privacy for sanitation facilities may also expose transgender or gender non-conforming people to harassment or violence. Alina, a transgender woman in Ukraine, told Human Rights Watch in 2014 that on one occasion, an employer discovered her identity as transgender because he observed her urinating. He subsequently sexually harassed her, leading her to quit her job.[161]

Households

Human Rights Watch research found a number of instances where poor household sanitation was linked to failures on the part of the authorities.

For example, in Harare, Zimbabwe, Human Rights Watch found in 2012 and 2013 that many people interviewed had indoor flush toilets—yet their systems were non-functional.[162] Almost no water came through the piped system, so people reported having to rely on alternative water sources to flush their toilets. When water access was very limited, many residents said that they defecate outdoors. When there was water, they said they would flush their toilets, but that the sewage pipes were often bursting, sewage at times came up from the toilet, and raw sewage flowing on the street was not uncommon.[163]

Even where sewage systems exist, and ostensibly function, households may still be excluded from connecting to them. Such exclusion may reflect broader discrimination or exclusion. For example, Human Rights Watch research in 2014 on violence in a majority Afro-Colombian city in Colombia raised concerns that high poverty rates and limited access to basic services created an environment for armed groups to thrive. Community members pointed to poor public services as an example of this socioeconomic exclusion. Just 0.3 percent of households in the city were connected to a sewage system, compared with 72 percent of Colombian households nationwide.[164] Such disparities in sewage connection between this city and the broader Colombian population may be indicative of unequal state investment.

As in other contexts, women and girls may face risks of violence when they lack safe and private household sanitation facilities. Women and girls living in areas of conflict may be at even greater risks when using the bathroom. A survivor of conflict-era sexual violence in Nepal described to Human Rights Watch in 2013 how a neighbor who had joined the rebel Maoist forces laid waiting for her outside a friend’s house as she went to the toilet one evening:

He grabbed me and dragged me to the fields. He was alone. He put his hand on my mouth so I could not shout. He raped me. … He kept me there for nearly two hours.[165]

Sewage removal and wastewater treatment is a major challenge for communities around the world, including in high-resource countries. It can contribute to water pollution and illness. Human Rights Watch research in First Nations in Canada in 2016 found that the inability to treat its sewage led one community to declare a state of crisis. According to its declaration:

Leakage [of septic fields] and frequent pump-outs are an ever-increasing problem. Both create health concerns, not to mention the smell…septic fields are leaking into [the community’s] nearby untreated drinking water source. … Our community has a pumper truck but we do not have a secure place to dump sewage or a secure way to get there. … In response to all these challenges and costs, consideration has been given to dumping on the man-made island. Result: Sewage disposal presents a health risk.[166]

In August 2015, the community’s chief told Human Rights Watch that the truck that pumped out septic tanks had “nowhere to take” the sewage and was “dumping it on the island … which can get into our water source that our kids bathe in.”[167] The community’s drinking water came directly from the surface water surrounding the island and the water operator in the community lamented, “At some point [the raw sewage] will reach the water.”[168]

The impact on individuals and communities where household sanitation is poor can extend beyond health or environmental harms. Sanitation workers who operate to fill the gaps in waste management may be exposed to harmful practices. So-called manual scavenging—the manual cleaning of excrement from private and public dry toilets and open drains—is a particularly horrific and stigmatizing practice that persists in parts of India and elsewhere in South Asia. Under centuries-old feudal and caste-based customs, women from communities that traditionally work as “manual scavengers” collect human waste from households with unimproved toilets on a daily basis, load it into cane baskets or metal troughs, and carry it away on their heads for disposal at the outskirts of the settlement. Human Rights Watch has documented the persistent health problems and assault on the dignity of people forced to engage in this practice, and the difficulties they face in trying to extricate themselves from this work.[169]

The rights abuses suffered by people who practice manual scavenging are mutually reinforcing. Constantly handling human excreta without protection can have severe health consequences. Those who do the work, however, also typically face “untouchability” practices. Discrimination that extends to all facets of their lives, including access to education for their children, makes it more likely they will have no choice but to continue to work as manual scavengers. Sona, from Bharatpur city in Rajasthan, India, described to Human Rights Watch in 2014 her first day of work and why she had no choice but to continue:

The first day when I was cleaning the latrines and the drain, my foot slipped and my leg sank in the excrement up to my calf. I screamed and ran away. Then I came home and cried and cried. My husband went with me the next day and made me do it. I knew there was only this work for me.[170]

Conclusion

States and donors working toward commitments made under Goal 6 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development should not stop at new resources alone. Efforts to address global sanitation and wastewater challenges should recognize the human right to sanitation, entitling everyone to sanitation services that provide privacy and ensure dignity, and that are physically accessible, affordable, safe, hygienic, secure, and socially and culturally acceptable.

To do so, governments at all levels and donors should address the contexts discussed in this report.

Plans and commitments should take into consideration public facilities, particularly those directly under government control or regulation. While using the bathroom is a deeply private affair, poor sanitation is not—it’s both an individual right and a public health and environmental concern. Human feces and wastewater can expose people to disease and pollute ecosystems and waterways. Human Rights Watch’s research puts into perspective the need for sanitation taking place in a public facility or sphere. It also demonstrates how poorly equipped states are in many instances to address sanitation in these contexts. For citizens to fully realize the right to sanitation, governments should directly provide sanitation services in facilities under their control and create the enabling environment for public facilities outside of their direct control, through regulations, enforcement, and funding.

Discrimination and inequality in access to sanitation can play a significant role in determining whether or not a person is able to realize their right to sanitation. It can also undermine investments governments and donors make to reach universal access to sanitation. Human Rights Watch research highlights discrimination in access to sanitation that occurs on the basis of gender and gender identity, disability, and caste or race in almost every context. Discrimination in access may actually serve to perpetuate other forms of inequality for marginalized populations. For example, women and girls need access to adequate sanitation in order to manage their hygiene during menstruation. When women and girls face discrimination in access to safe and private sanitation facilities and the material resources to manage their menstruation, their ability to realize other rights—including to education, health, work, and gender equality—may be undermined.

International human rights law addresses governments’ obligations related to sanitation. In 2009 the UN Human Rights Council passed a resolution recognizing that states have an obligation to address and eliminate discrimination with regard to access to sanitation, urging them to address effectively inequalities related to sanitation and calling on them to, among other affirmative steps, “adopt a gender-sensitive approach to all relevant policymaking in light of the special sanitation needs of women and girls.”[171] This should be considered in response to all populations at risk of discrimination in access to sanitation.

Eliminating discrimination in access to sanitation facilities requires that these facilities be safe and private. Human Rights Watch research reinforces common knowledge that toilets, open defecation fields, and bathing facilities can be the site of sexual violence and harassment, particularly against women, girls, and transgender people. Governments should ensure access to sanitation that is safe, secure, socially and culturally acceptable, and that provides privacy and ensures dignity. When women and girls are subject to rape or harassment simply for seeking to use a restroom, it is a sign that governments are failing in their obligations.

Lastly, states and donors cannot meaningfully pursue Sustainable Development Goal 6 or the realization of the right to sanitation without understanding the interdependence of access to sanitation with other human rights. Poor or no access to sanitation often occurs in the context of other human rights violations, and compounds their effects. Many of the dire situations detailed in the report happened within the context of arbitrary detention or other forms of deprivation of liberty, where people are already vulnerable to human rights violations and often lack recourse for poor conditions or other abuses. In other instances, lack of sanitation or wastewater management can contribute to water pollution that makes the right to safe drinking water less obtainable. Lack of sanitation facilities in schools can make already challenging educational environments even more difficult for adolescent girls. These compounding impacts of poor sanitation cannot be ignored by states and donors supporting them.

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Amanda Klasing, senior researcher and advocate in the women’s rights division, and Annerieke Smaak, senior coordinator in the women’s rights division. Richard Pearshouse, senior researcher in the health and human rights division, Bede Sheppard, Elin Martinez, Michael Bochenek, and Margaret Wurth of the children’s rights division, and Shantha Rau Barriga, director of the disability rights program, reviewed the report. James Ross, legal and policy director, and Tom Porteous, deputy program director, provided legal and program review respectively.

Olivia Hunter, publications and photography associate, Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, and Jose Martinez, senior coordinator, provided production assistance.

Human Rights Watch wishes to especially thank Inga Winkler of the Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University and Hannah Neumeyer of WASH United for their time and assistance in reviewing an earlier draft of this report.

We also wish to thank all those who shared their personal stories related to the very private issue of sanitation with Human Rights Watch researchers over the years.