Summary

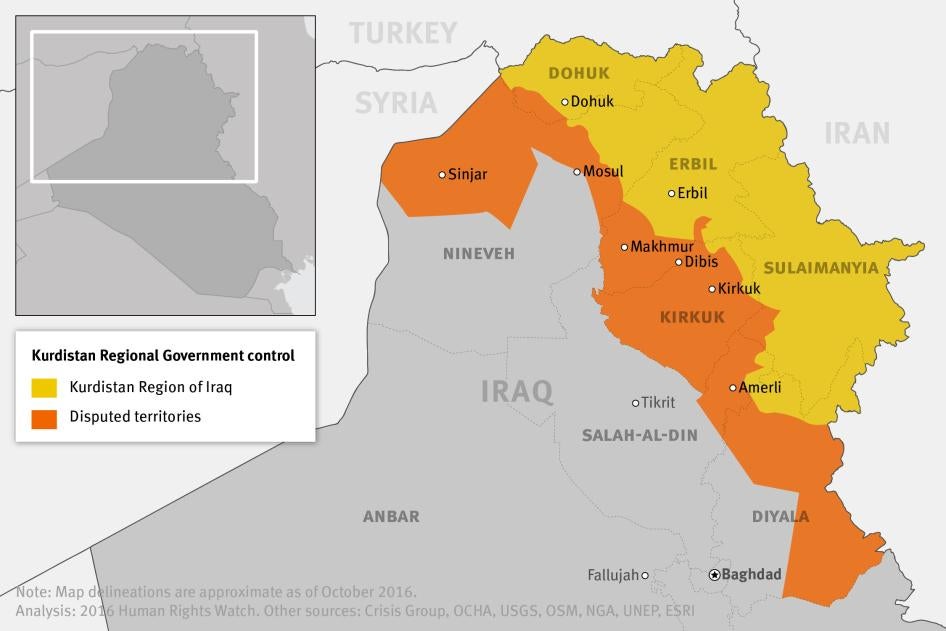

Since early 2014, when the extremist group Islamic State, also known as ISIS, launched its offensive in Iraq, fighting has displaced over three million Iraqis from their homes. Of these, an estimated 1.5 million Sunni Arabs now live in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), comprising the governorates of Dohuk, most of Erbil and Sulaimaniya governorates, and small parts of Nineveh and Diyala governorates. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) cites its openness to displaced Sunni Arabs as a sign of its “willingness to accommodate for any war-stricken individual or community, regardless of their race or religion.”

Many of the displaced Iraqis now residing in the KRI are from outside of the territory officially governed by KRI, from Nineveh and Kirkuk where KRG military forces, known as the Peshmerga, have battled ISIS to retake large areas of territory. The Peshmerga took Sinjar town in mid-November 2015 and a corridor southwest of Kirkuk city in October 2015. These are all so-called disputed areas: areas outside the KRI but which KRG officials claim should properly be part of the KRI. Before the arrival of ISIS they had been largely under KRG de facto control.

In March 2016, KRG forces along with forces mobilized by the Iraqi government in Baghdad began military operations aimed at defeating ISIS in Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city. The offensive to take Mosul, ISIS’ last major remaining stronghold in Iraq, has already caused an additional influx of tens of thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) to areas under the control of the KRG.

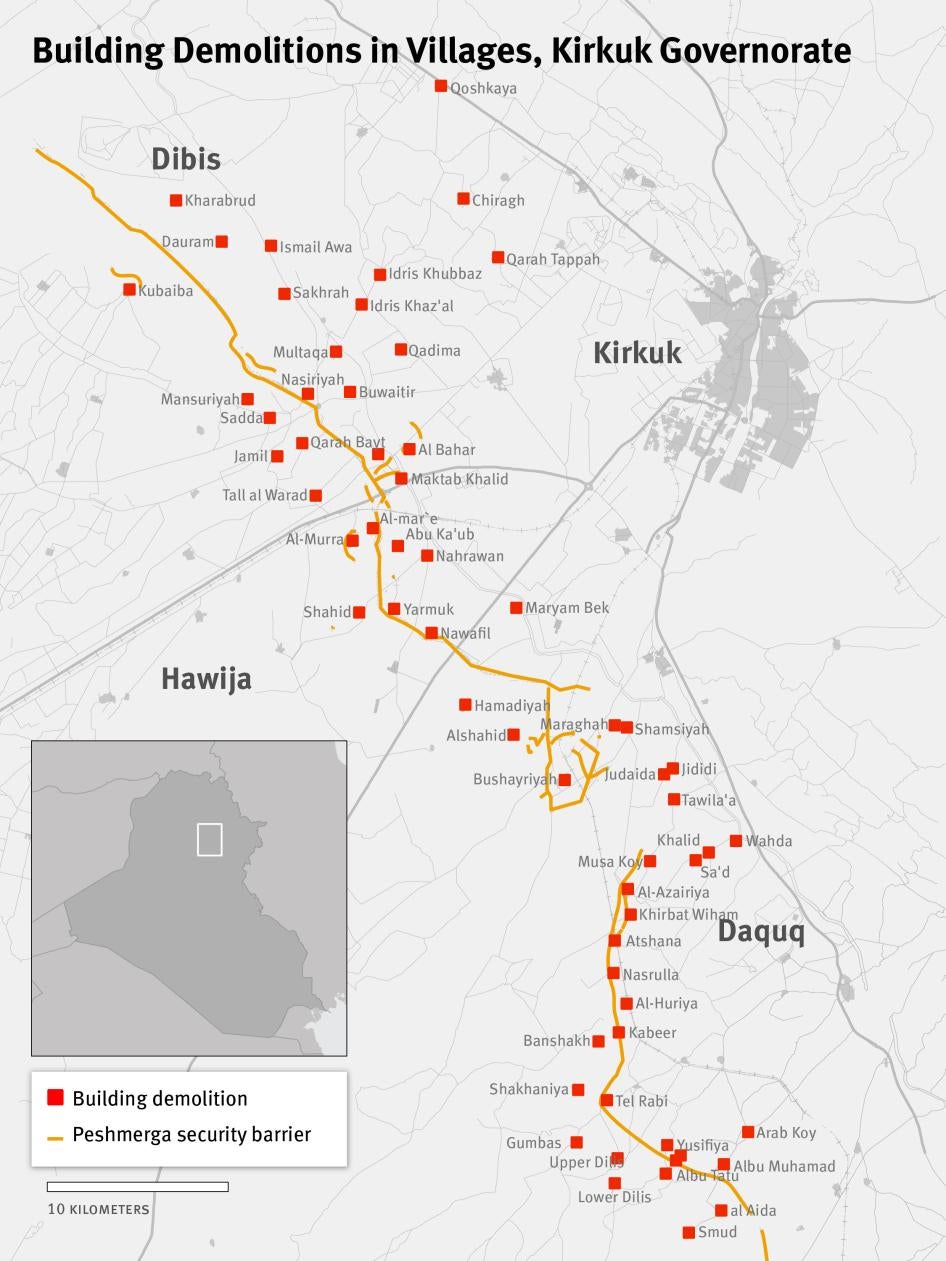

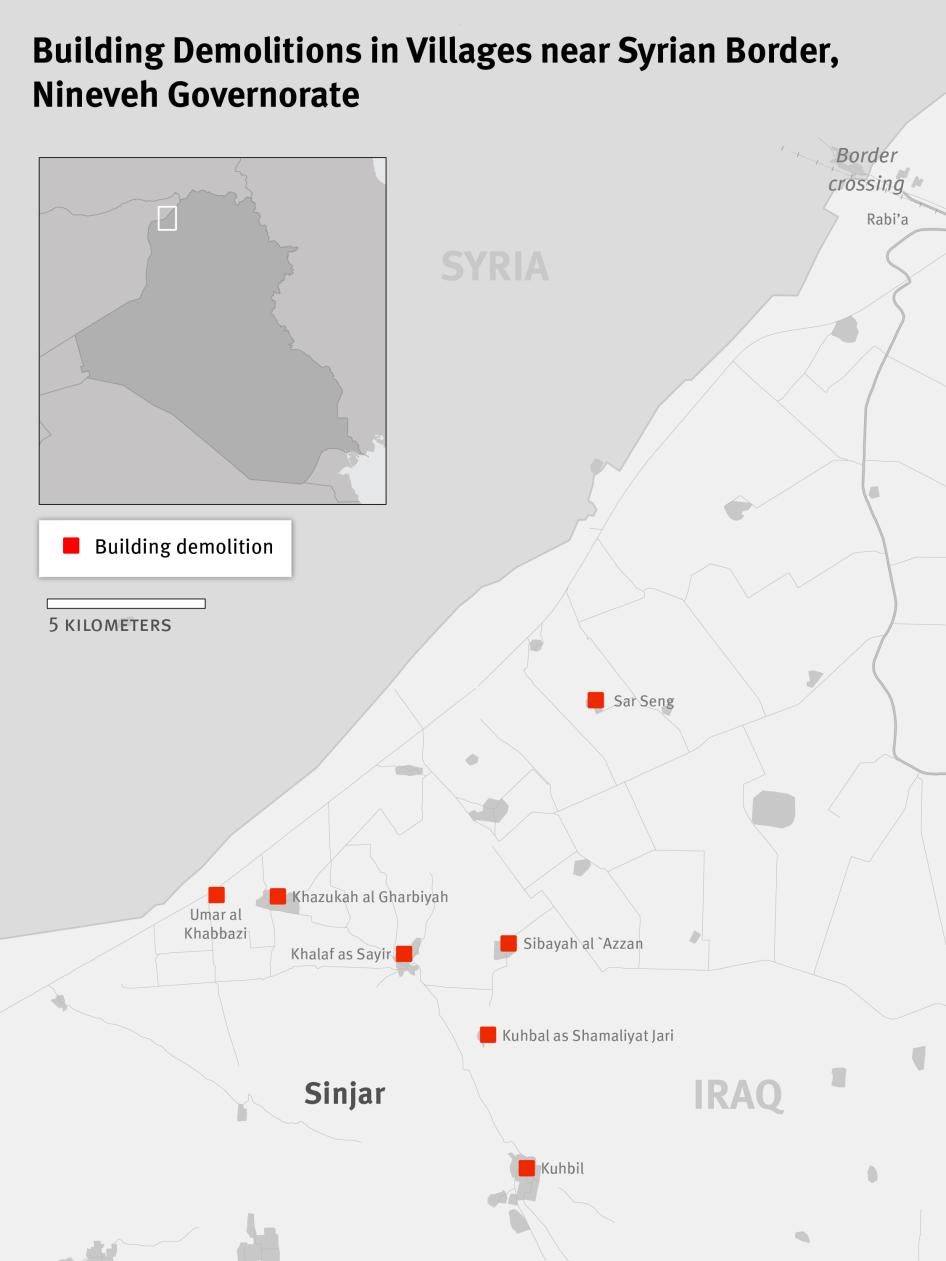

This report examines the conduct of KRG security forces in areas where they have defeated ISIS, all within the so-called disputed areas. The report finds a pattern of apparently unlawful demolitions of buildings and homes, and in many cases entire villages, between September 2014 and May 2016, in 17 villages and towns in Kirkuk and four in Nineveh governorate.

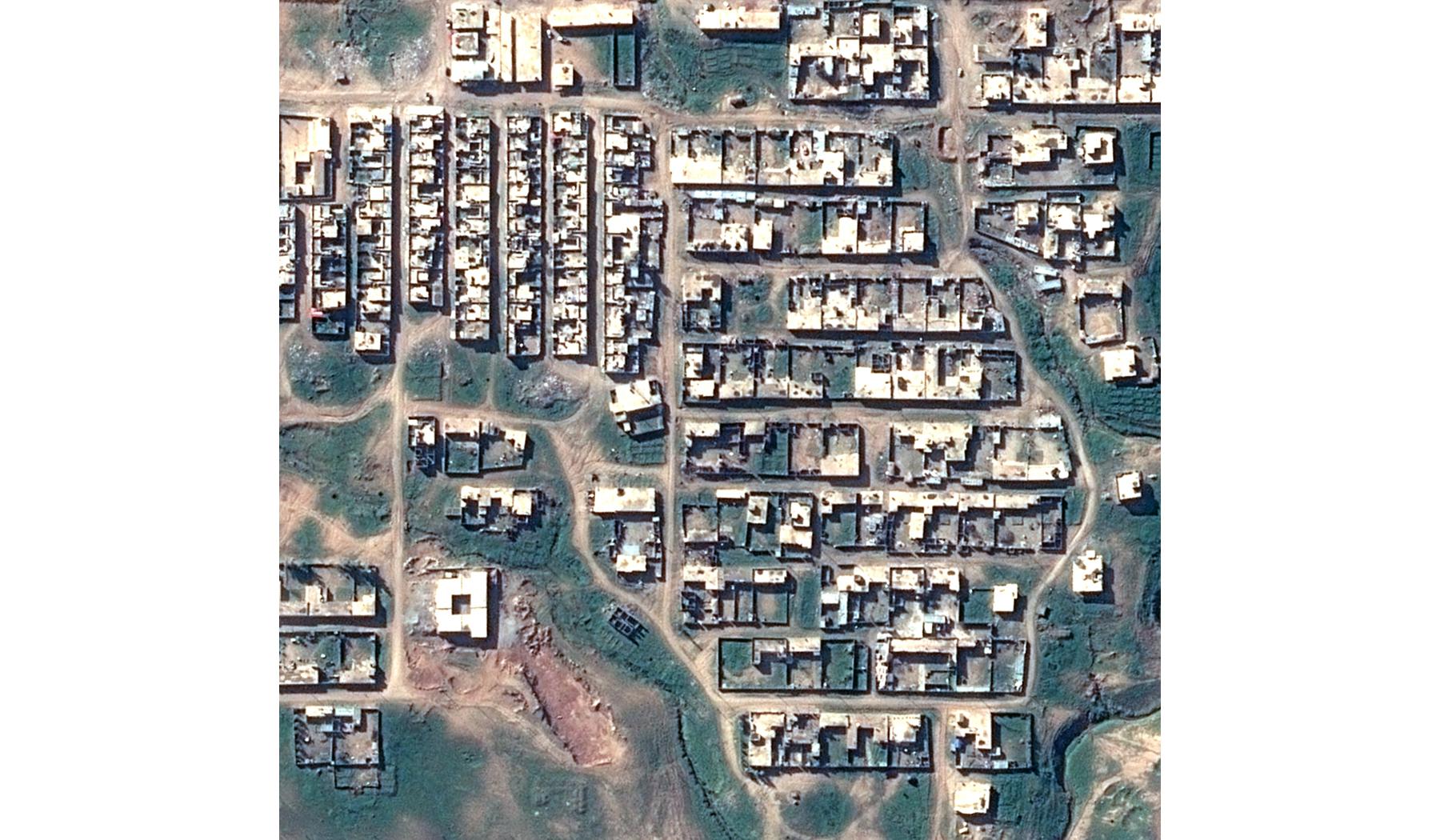

In a further 62 villages that researchers were not able to visit, satellite imagery provides evidence of destruction after Kurdish security forces recaptured them, but a lack of witness accounts did not allow for definitive conclusions as to the reasons and responsibility for the destruction.

On April 4, 2016, following a March 7 letter from Human Rights Watch summarizing our findings and an earlier Amnesty International report on alleged KRG violations, the KRG set up a committee to investigate allegations of unlawful destruction of property and movement restrictions of IDPs in the territory controlled by the KRG. According to KRG officials, the committee, comprising officials from the KRG Presidency, the Interior and Peshmerga Ministries, as well as the department of the Asayish, conducted fact-finding missions. The KRG on June 30, 2016 sent Human Rights Watch reports from their investigations regarding Nineveh, Erbil, and Kirkuk governorates (as well as Diyala governorate, which Human Rights Watch does not discuss in this report). These KRG reports addressed many, but not all, of the allegations contained in this Human Rights Watch report, and the KRG responses are reflected here.

With regard to destruction of buildings, KRG authorities stated that bombing of ISIS positions by the US-led coalition, in addition to mortars and artillery fire, caused much of the destruction. They also stated, and Peshmerga commanders told Human Rights Watch, that Peshmerga detonated ISIS-planted improvised explosive devices in order to defuse the devices, causing further destruction.

The KRG’s claims regarding the need to destroy homes to defuse improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in villages they captured from ISIS does not stand up to scrutiny. For example, in villages in Nineveh governorate visited by Human Rights Watch researchers, it appears that the KRG destroyed only Arab homes while leaving Kurdish ones intact. Researchers observed demolished Arab buildings in Bardiya next to intact Kurdish buildings, and the intact Kurdish part of Hamad Agha village next to the demolished Arab part, and next to Sheikhan, a demolished Arab village a short distance away.

In addition, in Kirkuk governorate, KRG security forces demolished buildings in Qarah Tappah and Idris Hindiya Qadima that ISIS never captured, and therefore is highly unlikely to have suffered damage during battles. Regarding Qoshkaya, another village that ISIS had not captured, Peshmerga officials said in a response on September 22, 2016 that they were unable to prevent “a segment of local residents” from destroying homes in the Arab quarter whose owners allegedly had joined ISIS. In Idris Khaz’al and Idris Khubbaz, Kurdish security forces used bulldozers to destroy homes, which is not a safe way to clear any booby-traps that ISIS may have planted. Satellite images also show arson in many villages in Nineveh, also not an effective mine clearance method.

The KRG, moreover, did not demonstrate an imperative military necessity for removing IEDs by detonating them and destroying the building in which they were planted. Peshmerga commanders said they lacked demining expertise, and IEDs had caused many casualties. If this was the case then cordoning off mined villages for later demining would have been safer than remotely detonating IEDs, which, besides destroying buildings, causes the dispersal of unseen explosives, making the area generally unsafe and complicating efforts to remove explosive remnants of war.

Another troubling issue is the apparent plan of the KRG not to allow Arabs to return to their villages. KRG President Masoud Barzani told Human Rights Watch in July 2016 that the KRG would not allow Sunni Arabs to return to villages that had been “Arabized” by former President Saddam Hussein. He said these were, in his view, rightfully Kurdish lands. Such territorial claims lend credence to the belief of many Arabs that KRG security forces may have carried out demolitions for the purpose of preventing or dissuading Arabs from returning there.

Central to the laws of war is the principle of distinction, which requires parties to a conflict to distinguish at all times between military and civilian objectives. Civilian objects may not be the target of attack unless they are being used for military purposes. The parties to an armed conflict have a duty to spare the civilian population and civilian objects from the effects of hostilities and to minimize damage to civilian objects. The laws of war prohibit the destruction or seizure of property unless required by imperative military necessity. They also prohibit indiscriminate attacks on civilians or civilian objects, including attacks that treat an entire area, such as a village, as a military objective.

Based on witness accounts and satellite images, Human Rights Watch concluded that KRG forces, for the most part Peshmerga, demolished buildings in at least 21 villages and towns after recapturing them from ISIS, in apparent violation of the laws of war. The extent and timing of much of the destruction in the cases reviewed in this report suggest that it cannot be explained by ISIS-planted IEDs or damage from coalition airstrikes, shelling or other actions during battle.

Human Rights Watch spoke with about 15 villagers who said that in Qarah Tappah, 14 kilometers west of Kirkuk city, they saw a joint force of Peshmerga, Asayish, and Kirkuk police on May 5, 2016 destroy 26 houses in the village. They told Human Rights Watch that most of the houses belonged to villagers who, they said, had joined ISIS in mid-2014. In their September 22, 2016 response, KRG officials said that some Qarah Tappah homes were destroyed by IEDs that security forces were unable to defuse. The destruction came the day after saboteurs blew up nearby oil wells, which security officials blamed on persons from Qarah Tappah. The destruction of these houses did not meet the test of imperative military necessity.

About 15 other villagers from Idris Khaz’al, Idris Khubbaz and Idris Hindiya Qadima, 20 kilometers west of Kirkuk city, said that they saw Peshmerga, Asayish, and armed Kurdish civilians operating under Peshmerga control loot and then burn or demolish dozens of homes with bulldozers in the first days of February 2015. Those interviewed said they did not see ISIS plant IEDs during its brief 36-hour occupation of Idris Khaz’al and Idris Khubbaz, and that ISIS never took Idris Hindiya Qadima during its assault on the area on January 30, 2015. Satellite imagery over the following week shows most of the destruction in the three villages occurred around February 5, after the Peshmerga recaptured the area.

In its March 2016 response to Human Rights Watch, the KRG wrote that in the three Idris villages, ISIS “could not plant IEDs in this district as Peshmerga forces immediately launched a counterattack to liberate these areas.” However, in its June 2016 response, the KRG stated that the “large level of destruction [in Idris Hindiya Qadima] was due to IS [Islamic State] planted IEDs and the exchange of fire … between IS and the Peshmerga forces.” For Idris Khaz’al, the KRG’s June response stated that coalition airstrikes and IEDs “unavoidably detonated in the cleaning-up mission” destroyed three quarters of the 84 destroyed properties. For Idris Khubbaz, causes of the destruction “were the same as in Idris Khaz’al.”

In the village of al-Murra, a village that ended up completely destroyed, three villagers said that Peshmerga in late February or early March 2015 forced them to leave on account of an impending battle with ISIS. In July 2015, after they returned and after the defeat of ISIS there, they observed Peshmerga demolishing homes.

The KRG’s September 2016 response said that al-Murra and the nearby village of al-Shahid were approximately 3 kilometers beyond the Peshmerga frontline “and do not constitute an area which is under the authority of the Peshmerga forces.” In a separate communication in September 2016, KRG officials said that destruction of homes in the two villages was “directly related to the fact that the properties belonged to individuals who had joined the terrorists of the Islamic State and that those houses were being used by the terrorists with the aim of strengthening their presence in these villages.”

Villagers told Human Rights Watch that al-Murra had come under Peshmerga control as of March 2015, and that some homes were damaged, but none demolished. Satellite images show that the complete destruction of al-Murra occurred between May 20 and November 12, 2015, with damage signatures consistent with the use of high explosives and heavy machinery. From the accounts of villagers, it appears that the demolitions occurred after a short battle for al-Murra that lasted a few hours in early July 2015, in which the Peshmerga retained control.

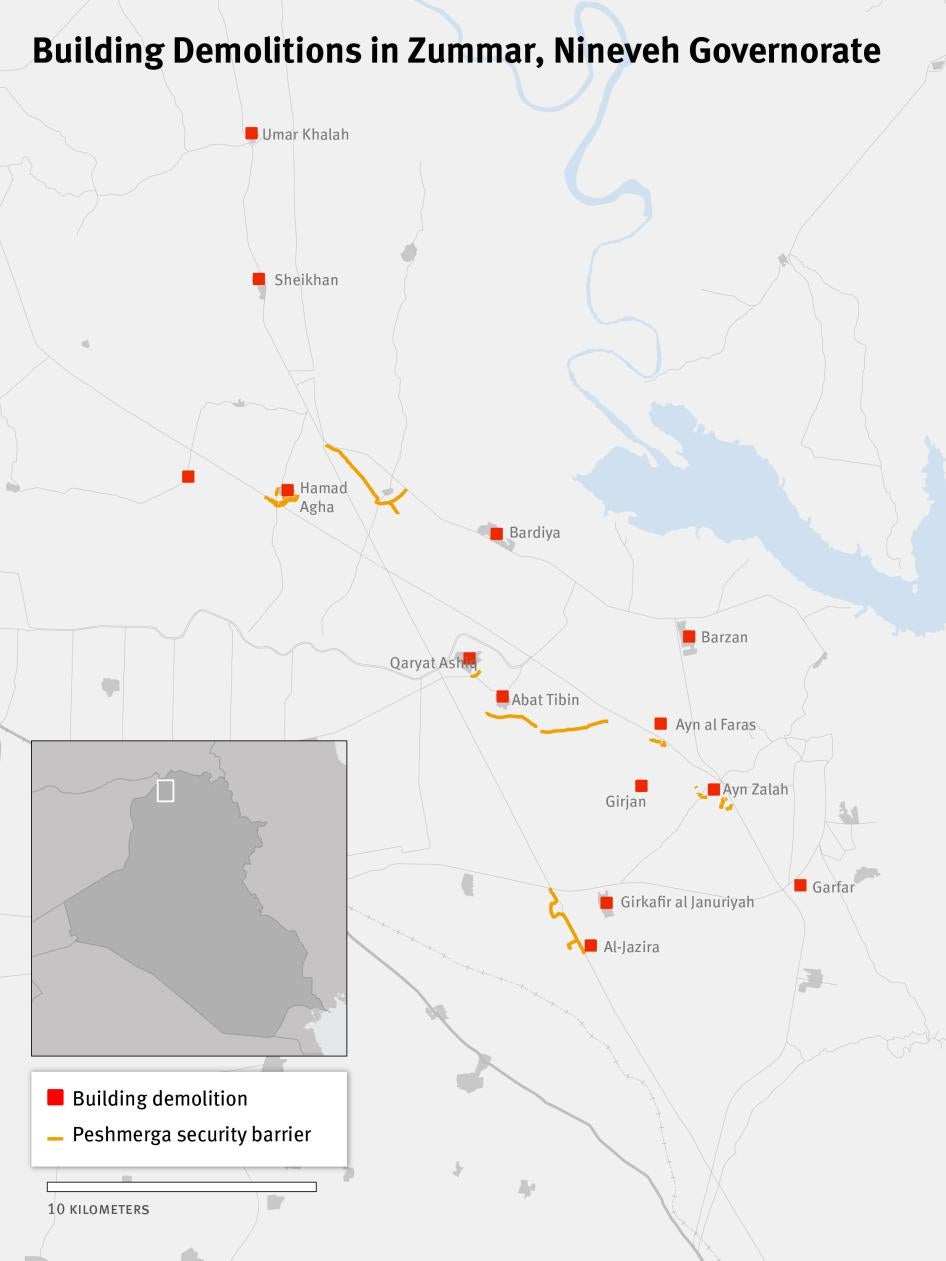

In Nineveh governorate, about 15 witnesses said that Peshmerga and Asayish forces and villagers demolished homes in Sheikhan, Hamad Agha, Bardiya, and Barzan, all in the Zummar subdistrict. Peshmerga recaptured these areas from ISIS by late August 2014.

Five Kurdish farmers from the Kurdish village of Kani Azeir (Ewes), 2 kilometers west of Sheikhan, told Human Rights Watch that ISIS had carried out some destruction in Sheikhan during its three-week presence there in August 2014. But they also said that they themselves, along with other Kurdish farmers and Peshmerga forces, participated in the burning of homes and demolition of the village after its recapture. A Kurdish police officer from the nearby village of Hamad Agha told Human Rights Watch that he joined Peshmerga and local civilian Kurds and Yezidis in demolishing Sheikhan. Human Rights Watch visited Sheikhan on August 3, 2015 and found that almost no structure, with the exception of a green mosque, remained intact.

Human Rights Watch researchers visited Hamad Agha, which has a Kurdish district and an Arab district, on August 3, 2015, and found only the Kurdish district intact. The Kurdish policeman from the village told Human Rights Watch that he participated with Peshmerga in demolishing the Arab district of Hamad Agha.

In the village of Bardiya, 7 kilometers southeast of Ewes, a Kurdish shopkeeper told Human Rights Watch that he advanced with the Peshmerga as a volunteer and, together with fellow Kurdish civilians and Peshmerga and Asayish forces, destroyed the houses of Arab townspeople “because they were Daesh [ISIS].” Human Rights Watch met with a group of about 15 displaced people from a nearby village squatting on the outskirts of Bardiya. Several of them told Human Rights Watch that they saw Peshmerga and Kurdish civilians destroy houses in Bardiya. The others agreed. They said that the Kurdish civilians told them they had once had homes in Bardiya before Arabs moved in as part of former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s Arabization campaign.

Satellite imagery shows Sheikhan, Hamad Agha, parts of Bardiya, and Barzan leveled to the ground, and indicates that the destruction occurred after the late August or early September 2014 recapture of the area by Peshmerga from ISIS. The destruction continued into 2015.

The KRG stated in its response to Human Rights Watch that 85 properties in Sheikhan and 120 houses in the Arab part of Hamad Agha were destroyed by exchanges of artillery and mortar strikes, along with 523 homes in Barzan, “including those that were subject to IS IEDs.” The KRG said that “large groups of Yezidis” burned homes there, despite Peshmerga efforts to stop them, in retaliation for people from Barzan allegedly participating in atrocities against Yezidis. The KRG said that the reason why Barzan was so severely targeted was because it was the “epicentre of the IS groups’ support base in the general Sinjar area as well as a recruitment hub for IS fighters and IS commanders.”

Satellite imagery shows that more than half of the destruction in Sheikhan occurred between November 2014 and March 2015, a further 30 buildings were destroyed thereafter, and at least a quarter of the destruction in Barzan took place after November 5, 2014, well after the Peshmerga took control of both villages. Public sources indicate there were no attacks by ISIS on Sheikhan or Barzan after late August 2014.

The fact that in Bardiya, Ewes, Sheikhan, and Hamad Agha Kurdish areas were left intact while nearby Arab areas were destroyed undermines the KRG’s claim that ISIS or its booby-traps were partially responsible for the widespread destruction in these locations. Equally, the fact that the bulk of the destruction seen in satellite images occurred after the Peshmerga had taken control of these villages undermines the claim that airstrikes or shelling were the primary cause of the destruction (in addition to the fact that satellite imagery analysis points to the use of fire, heavy machinery and high explosives). Furthermore, on the basis of information thus far provided by the KRG, it is not possible to conclude that the destruction of booby-trapped homes occurred for reasons of imperative military necessity.

In Order No.3 of March 17, 2016, attached as an appendix to this report, KRG President Masoud Barzani commanded, with regard to “all possible situations, … the protection of towns and villages which have been liberated by Peshmerga forces.” The KRG fact-finding mission begun in April 2016, and reflected in the KRG June 30 response to Human Rights Watch, appears to be the first KRG field investigations into possible violations of the laws of war by Kurdish forces. However, Human Rights Watch is not aware of any criminal investigations or prosecutions launched by KRG authorities with regard to alleged violations, including unlawful destruction of civilian property.

Governments of several countries in the international coalition against ISIS, including the United States, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Canada, Russia, Iran and central and southern European states, support the KRG with military hardware and training. Some carry out joint military operations with KRG forces. No officials of these countries have publicly spoken out about the need for the KRG to end unlawful building demolitions in violation of the laws of war and international human rights law and to hold those responsible to account. The US has Special Operations forces advising Peshmerga on the front lines and has trained over 1,000 Peshmerga. In April 2016, Defense Secretary Ashton Carter said the US would provide US$415 million in financial assistance to select Peshmerga units. Since February 2015, Germany has run an international training center for Peshmerga forces in Erbil. Following reports in January 2016 that German-supplied machine guns to the Peshmerga appeared on the black market and a report that same month by Amnesty International that documented Kurdish forces’ responsibility for destroying buildings and restricting Sunni Arabs’ freedom of movement, the KRG told the German government it would investigate these allegations.

What happens if the US-led coalition together with Iraqi government and KRG forces succeeds in the campaign to expel the group from Mosul is a pressing question. The violations by KRG security forces of international law prohibitions against unlawful property destruction is a recipe for continued conflict even if ISIS is dislodged and ceases to hold territory in Iraq.

KRG President Masoud Barzani has said he plans to hold a referendum on Kurdish independence from Iraq in 2016, and Kurdish officials have made no secret of the fact that they consider much of the area recaptured from ISIS outside the KRI as historically Kurdish lands that should be part of an enlarged KRI or an eventual independent Kurdish state. These political goals do not justify unlawfully demolishing homes and preventing individuals from returning to their homes.

Human Rights Watch calls on the KRG to investigate the allegations of laws-of-war violations detailed in this report and to hold those responsible to account. The KRG’s fact-finding missions may be a first step to such accountability, but a number of incidents and allegations remain unaddressed, and in other instances the KRG’s findings do not correspond to those of Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch also calls on the United States, Germany and other countries providing military assistance to the KRG to urge it to investigate these allegations and to investigate the role of its own military assistance in these alleged violations. The UN Human Rights Council should broaden the investigation mandate of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights on abuses by ISIS to include serious violations by all parties, including Kurdistan security forces. The council should also appoint a Special Rapporteur on Iraq to monitor and report on the situation of human rights there and recommend measures to ensure accountability for human rights abuses and law-of-war violations.

Recommendations

To Kurdistan Regional Government

- Investigate violations of the laws of war and of human rights law mentioned in this report, in particular demolitions of buildings and homes;

- Discipline members of Kurdish security forces, including Peshmerga, Asayish and counter-terrorism forces, implicated in violations of international humanitarian law, and allow the military or civilian judiciary, as appropriate, to independently investigate, and where the evidence warrants, prosecute these forces, including officials responsible for laws-of-war violations as a matter of command responsibility;

- Prosecute Kurdish civilians implicated in violations of international humanitarian law and human rights law;

- Take all necessary steps to end unlawful destruction of and damage to civilian property by KRG forces in the absence of imperative military necessity, including attacks on property that indiscriminately treat entire villages as military objects;

- Provide fair compensation and alternative housing to those whose homes KRG security forces have unlawfully destroyed.

To the United States, Germany and Other States Supporting KRG Forces

- Investigate whether foreign military assistance, including weapons and munitions transfers and military training, contributed to the laws-of-war violations documented in this report. End military assistance to units involved in these violations and explain publicly any suspension or end to military assistance, including the grounds for doing so;

- Communicate to KRG authorities the need to undertake credible investigations into allegations of serious laws-of-war violations, in order to maintain transfers of weapons and military training;

- Urge KRG to publicly report, no later than June 30, 2017, on progress toward accountability for laws-of-war violations;

- Ensure that training of Kurdish security forces includes robust instruction on the principles and application of the laws of war, particularly with regard to home demolitions;

- Vet for human rights abuses and laws-or-war violations all units and agencies of KRG security forces that receive military aid and security assistance;

- Undertake regular joint monitoring visits to security forces training sites to assess training effectiveness, including on human rights;

- Publicly report violations of agreements by KRG security forces on end-use of military transfers.

To United Nations Institutions and Agencies

- The UN Human Rights Council should extend the investigation mandate of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights on abuses by ISIS and broaden it to include serious violations by all parties in Iraq, including Kurdish security forces;

- The Council should establish a mandate of Special Rapporteur on the situation in Iraq, in order to monitor and regularly publish reports on the situation of human rights and recommend measures to ensure accountability;

- The UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Iraq and the UN Development Programme’s Stabilization Fund should include housing for returning displaced persons and ensure their right to restitution or compensation for loss of property.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews with around 120 people in Nineveh, Dohuk, Erbil, Sulaimaniya, and Kirkuk governorates, during five field visits to areas of Iraq controlled by Kurdish security forces between September 2014 and May 2016. Those interviewed included Arab Iraqis displaced by the fight against ISIS in Iraq. Human Rights Watch researchers spoke to almost all the interviewees in person and in Arabic. One interview was conducted in Kurdish with translation. Human Rights Watch researchers also visited locations in Nineveh, Erbil, and Kirkuk governorates where Kurdish forces allegedly carried out destruction of homes. We also spoke to Peshmerga and KRG government officials during these visits.

We informed all interviewees about the purpose and voluntary nature of the interviews, and the ways in which we would use the information, and obtained consent from all interviewees, who understood they would receive no compensation for their participation. For reasons of personal security Human Rights Watch has withheld the names and identifying information of those interviewed, except for officials or those who agreed to be named.

Human Rights Watch is grateful for the cooperation we received from KRG authorities and security officials during our visits to areas under the control of KRG security forces, and in particular the assistance of Asayish officers in Nineveh, and Peshmerga officers in Kirkuk. Gen. Sheikh Jafar Mustafa of the Peshmerga gave generously of his time and expertise in answering our questions at his base in Sulaimaniya in December 2015.

Human Rights Watch conducted a detailed damage assessment of areas in Zummar, Rabi’a and parts of al-Shamal subdistricts in Nineveh, and areas west and southwest of Kirkuk city, using a time series of very high resolution commercial satellite images recorded on 35 separate dates in 143 towns and villages from June 2014 until March 2016. In each case, the time series of satellite images was taken before, during and after the destruction.[1] We used satellite imagery to identify areas of destruction, to quantify damage levels, to evaluate and corroborate witness statements, and to assess the scale, distribution, and timing of the destruction of buildings. Further, we used satellite imagery to determine the probable methods of destruction, as well as to identify damage from airstrikes and any artillery and mortar fire that occurred during battles between ISIS and Peshmerga forces and distinguish such damage from demolitions carried out after the battles.

In this report, Human Rights Watch uses the terms Peshmerga to refer to the armed forces of the KRG, and Asayish to refer to the police forces of the KRG. The term “Kurdish forces” is used in cases where the witnesses could not specifically identity the type of force or where other armed forces, such as those of the Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), Yezidi armed groups, and armed Kurdish civilians were also active.

Human Rights Watch communicated its findings to the KRG in January 2015, October 2015, March 2016, and September 2016. The KRG responded each time, including a detailed report on March 26, 2016 and the results of its fact-finding missions on June 30, 2016 (references to “the KRG response” refer to the June 30 response unless otherwise indicated). In July 2016, Human Rights Watch met with President Barzani, Foreign Minister Falah Mustafa, Interior Minister and acting Minister of Peshmerga Affairs Karim Sinjari to discuss our findings. The relevant parts of the KRG responses are reflected in this report. Human Rights Watch maintains a dialogue with the KRG to assess the facts presented in this report and any resulting remedies. Human Rights Watch previously published some findings of September and December 2014 field visits on February 25, 2015, and of a January 2016 visit on April 5, 2016.

I. Background

Iraqi Kurdistan has enjoyed relative stability and until recently strong economic growth in the aftermath of the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, carving out a politically autonomous status for the region recognized in Iraq’s 2005 constitution.[2] The Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) has a regional parliament situated in the capital, Erbil. Its internal border is the Green Line demarcating the status quo between Iraqi government and Kurdish forces as of 1991, including all of Dohuk governorate, and large but not all parts of Erbil and Sulaimaniya governorates, and small parts of Nineveh and Diyala governorates. Since 2003, the Kurdish sphere of influence has extended into the Nineveh Plains and Sinjar in Nineveh governorate, Makhmur in Erbil governorate, Kirkuk city in Kirkuk governorate, Tuz Khurmatu in Salah al-Din governorate, and Khanaqin and Jalawla in Diyala governorate. These areas are home to many Kurds and other ethnic and religious minorities such as Yezidis, Christians, Shabak, and Kaka’is, in addition to Arab Iraqis.

In the second week of June 2014, forces of the Islamic State, also known as ISIS, took over Mosul in Nineveh and advanced into Salah al-Din, and Kirkuk governorates. Iraqi government army forces in the region failed to put up resistance and melted away, but the Peshmerga, the armed forces of the Kurdistan Regional Government, moved in, securing areas around Kirkuk city and elsewhere. In August 2014, ISIS drove Peshmerga forces from the Sinjar and Nineveh Plains area up to Mosul Lake. After Kurdish forces repelled a brief ISIS advance on Erbil, they held a frontline along the Greater Zab River to Gwer (Quwayr) and Makhmur in Erbil governorate, and to Kirkuk city along the mountain ridges running from northwest to southeast.

By the end of 2014, Peshmerga had recaptured much of the Nineveh Plains, an area reaching from Sinjar mountain in the north to Mosul Lake. They retook Sinjar in November 2015, and pushed south and west from Kirkuk at various points in 2015. In Diyala governorate, Peshmerga forces in late November 2014 retook Jalawla from ISIS, ending its three-month presence there.[3]

By late 2015, Kurdish forces had recaptured from ISIS much of the territory that, although officially outside of the KRI, had been within the Kurdish sphere of influence since 2003 with a Peshmerga security presence. On March 24, 2016, Iraqi army units that had moved to Makhmur in coordination with Peshmerga forces began an offensive to recapture Mosul.

***

After 2003, the US-led occupation administration, the Coalition Provisional Authority, established the Iraq Property Claims Commission (IPCC) with a deadline of December 31, 2007 to resolve property disputes arising from Saddam Hussein’s Arabization and other policies.[4] Article 140 of the 2005 constitution mandates the Iraqi government:

[t]o remedy the injustice caused by the previous regime’s practices in altering the demographic character of certain regions, including Kirkuk, by deporting and expelling individuals from their places of residence, forcing migration in and out of the region, settling individuals alien to the region, depriving the inhabitants of work, and correcting nationality.[5]

Those practices included the genocidal Anfal Campaign against Iraqi Kurds from 1987 to 1989 that killed over 100,000 people and levelled large areas south and east of Kirkuk city.[6]

The Iraqi government in 2006 replaced the Property Claims Commission with the Iraq Commission for the Resolution of Real Property Disputes (CRRPD), maintaining the mandate but introducing other changes. By September 2007, the commission had decided around 37,000 cases out of a caseload of 135,000, but the changes to the CRRPD procedures meant some 9,000 of those 37,000 cases had to be reviewed, and the remainder had poor rates of enforcement for restitution or compensation.[7] By 2009, the mechanism had clearly failed to provide redress, and tensions significantly increased around property ownership and demography in Kirkuk, Diyala and Nineveh.[8] By 2011, the commitment of senior officials in Baghdad to implement property restitution had significantly waned.[9] By the time ISIS forcibly took control of some of the disputed territories in June 2014, and the Kurds sent armed forces to secure Kirkuk, prospects for law-based means of redressing past violations had faded. In December 2014, Baghdad and Erbil agreed informally on revenue sharing in an agreement that appears not to have addressed the resolution of personal property disputes through adjudication or a mechanism for addressing claims for political self-determination.[10]

***

Since 2003, officials of the major Kurdish parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) of President Barzani and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) of Jalal Talabani, a former president of Iraq, have opened party offices in many towns in the Kurdish sphere of influence south of the KRI.

Human Rights Watch research in Nineveh governorate in 2009 found that Kurdish authorities engaged in a “two-pronged strategy: they have offered minorities inducements while simultaneously wielding repression in order to keep them in tow.”[11] Minorities of the Nineveh Plains, such as the Shabak, Yezidis and Chaldeo-Assyrians, confronted “Kurdish authorities’ heavy handed tactics, including arbitrary arrests and detentions, and intimidation, directed at anyone resistant to Kurdish expansionist plans.”[12] On June 10, 2016, Hadi Halabjayi, a Peshmerga commander, said of areas around Khazir in Nineveh governorate captured two weeks earlier, “These territories are Kurdistan's now. We will not give them back to the Iraqi army or anybody else.”[13]

The International Crisis Group, a conflict resolution organization, wrote in May 2015 that:

The KDP and PUK follow similar, though uncoordinated, strategies to further dominance in their areas of influence: the KDP in the Ninewa plain and points of access to neighboring Kurdish-populated areas of Syria, the PUK in Kirkuk and Diyala governorates … Kurdish forces make sure to “liberate” Sunni Arab-populated areas only after striking deals with local leaders that solidify their control by imposing their own leadership and making the local figures dependent on them for the protection and services essential for return of the displaced.[14]

A map published on the website of the KRG’s presidency shows the extent of Kurdish influence—in many parts, security and political control—in the disputed territories outside the KRI.[15] KRG Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani, in a July 2016 interview, said, “We will decide the extent of our borders by what has been liberated with the bold of our Peshmerga. … Whether we remain with Iraq or be independent or be part of a federation or confederation, our priority will remain the delineation of our borders.”[16] According to Falah Mustafa, the head of the KRG’s foreign relations department, “All the areas that have been liberated by the Peshmerga forces, our forces will stay there.”[17] KRG Spokesperson Safeen Dizayee said the Peshmerga “will not stop their advances until all Kurdistan’s territories in the Ninevah region are liberated.”[18] Gen. Sheikh Jafar Mustafa, the senior Peshmerga commander, told Human Rights Watch in December 2015 with regard to southern Kirkuk governorate:

All the villages we retook in Daquq in August [2015] had been part of Arabization. This land is Kurdish land and we will never give them the chance to take this land again. We will not let the Arabs take this land again.[19]

II. Building Demolition

The laws of war prohibit the destruction or seizure of the property of an adversary, unless required by imperative military necessity, defined by the International Committee of the Red Cross as “the necessity for measures which are essential to attain the goals of war, and which are lawful in accordance with the laws and customs of war.”[20]

When destruction is permitted as a matter of imperative military necessity, it must not be disproportionate, that is, excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage, and limited to the circumstances at the time, that is, not to past or possible future military use. Nor does the notion of military necessity allow for the partial or total destruction of a wide area, such as a neighborhood or village, regardless of proximity to frontlines. Those responsible for the wanton destruction of civilian property should be investigated for possible war crimes and held to account.

Many of the villages and towns that Kurdish forces recaptured from ISIS over the past two years have been scenes of widespread destruction, and some are now devoid of civilian life. In many cases, the damage to homes resulted after Peshmerga forces had full control of the area.

Human Rights Watch collected information on 83 towns and villages that bore signs of significant destruction: 61 in Kirkuk governorate, 21 in Nineveh governorate, and one, Abu Shita, in Erbil governorate. For this report, Human Rights Watch investigated 21 of the 83 towns of villages where available evidence suggested building destruction had been unlawful (17 in Kirkuk and 4 in Nineveh governorates). Of these 21 towns and villages, we visited 13 that bore signs of significant destruction (9 in Kirkuk governorate and 4 in Nineveh governorate).[21] In addition, we spoke with residents and witnesses to destruction in eight additional villages and towns (all in Kirkuk governorate).[22] Seven of the 13 sites visited were empty of residents.[23] For the other 62 villages and towns, satellite imagery shows significant destruction consistent with the use of fire, heavy machinery and high explosives, distinct in appearance from destruction resulting from air strikes and heavy ground fire prior to ISIS’s retreat from these locations, but a lack of witness accounts does not allow for definitive conclusions about the circumstances of and responsibility for destruction in these locations.

Human Rights Watch found that the causes of the destruction of buildings varied. ISIS blew up some houses, usually the homes of Iraqi security officials, according to residents from six villages and towns.[24] US-led coalition airstrikes also caused damage, residents of three villages said and satellite imagery revealed. In at least in one village, Kubaiba in Kirkuk governorate, damage from airstrikes was considerable and we did not list it among the 21 villages and towns where we found evidence of unlawful destruction following KRG control of the area.[25]

Almost all of the 83 villages and towns visited or assessed by Human Rights Watch were either completely or partially razed to the ground, resulting in the destruction of thousands of civilian homes, as well as administrative and commercial buildings. Human Rights Watch determined the timing of this destruction by comparing multiple satellite images recorded before and after the dates on which residents said the Peshmerga had recaptured the areas from ISIS. In many locations, the demolition of buildings occurred over a period of weeks and even months after the Peshmerga took control. Human Rights Watch determined that building demolition in several locations was initially done by setting fire generally to smaller, single story buildings, followed by the demolition of larger, multi-story buildings with heavy machinery and high explosives.

Peshmerga officers in one area, Daquq, told Human Rights Watch that they blew up many structures that ISIS had booby-trapped in order to protect themselves against accidentally setting off hidden bombs. In three villages, ISIS could not have planted improvised bombs because it had never captured the villages in the first place. In two other cases ISIS controlled the village for less than two days; residents said ISIS did not plant improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in that time and that they saw Peshmerga carry out destruction with bulldozers.[26]

Gen. Sheikh Jafar Mustafa, a senior Peshmerga commander for the Kirkuk area, told Human Rights Watch that 80 percent of casualties his men had suffered were due to IEDs planted by ISIS.[27] He said that his men were able to defuse only some IEDs, and that the Peshmerga “destroy[ed] the houses with TNT, especially if we think ISIS would use the village again.”[28] Colonel Ibrahim, a Peshmerga officer on the frontline in Daquq, said, “We sometimes have to set off any explosives from a distance to protect ourselves.”[29]

Colonel Ibrahim described his men’s work around Al-Bu Muhammad, Tell Rabi’, and Dilis, west of Daquq, that the Peshmerga retook on August 15, 2015:

The demining team has also had a lot of casualties. The IEDs are quite sophisticated. For example, we found two metal shish kebab sticks laid next to each other on the ground, with just a thin divider between them. When it gets disrupted and the sticks touch, the mine goes off. Another way is to have two loose and exposed wire ends close to each other inside a plastic tube, but not touching. When you disrupt it by stepping on it or driving over it, the wires touch and the IED goes off. Other IEDs we found have extremely thin wire that is not really visible attached to doors, and when you open the doors, they go off. Sometimes the entire house explodes, but mostly only one room. Others are remotely detonated with cell phones. ISIS saws through electricity poles, and uses the hollow opening to stuff it with ammonium explosives. Because of the tight packing in a metal tube, there is a lot of damage when it explodes.[30]

Brig. Araz Abd al-Qadir Abd al-Rahman, the Peshmerga commander in the Daquq area, told Human Rights Watch that because ISIS mined so many houses, “We shell villages before going in to set off some of the IEDs.”[31]

Devices that explode due to contact with a person fall under the definition of an antipersonnel landmine, which are prohibited under the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty. But for destruction of civilian property to be lawful, KRG forces would have to have an imperative military necessity to do so. The requirement of imperative military necessity means that there was no less-destructive alternative to achieving that aim, and that the military operation must have some concrete link to actual or anticipated fighting. It is unlawful to destroy a civilian object without specific evidence that it is being put to military use or is about to be so used.

Human Rights Watch spoke to three officials with demining agencies with experience working in the northern part of Iraq. All agreed that in most circumstances it would be better to cordon off mined areas, including entire villages if necessary, and try to carefully defuse the mines at a later time because uncontrolled explosions risked dispersing explosives throughout the rubble, making the area, and later clean-up, extremely unsafe.[32]

Human Rights Watch is not aware, and the KRG has not claimed, that Peshmerga forces had to establish military positions inside these villages (such as they did in Gwer and Abu Shita, in Erbil governorate, where destruction also took place). Destruction of villages weeks or months after the Peshmerga retook them from ISIS indicates that mines and booby-traps in villages did not present military obstacles whose removal was an imperative necessity. Destruction of buildings and entire villages in order to pre-empt high casualties in demining teams would also not satisfy the requirement that the destruction offer a definitive military advantage at the time of destruction. The Peshmerga could have cordoned them off to protect the lives of their forces and demining teams.

In its March 26, 2016 response to Human Rights Watch, the KRG wrote that coalition airstrikes or fighting between the Peshmerga and ISIS were responsible for some of the damage to buildings (see below for details). On April 4, 2016, following Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International reports of Peshmerga violations, the KRG set up a committee to conduct field visits and investigate claims of unlawful destruction.[33] In this report we reference relevant conclusions from the KRG’s fact-finding mission, which the KRG sent to Human Rights Watch on June 30, 2016. Dr. Dindar Zebari, the head of the committee, told Human Rights Watch on May 25, 2016 that the government might consider compensation for those whose homes Peshmerga forces had arbitrarily destroyed.[34] On May 19, 2016, Fuad Hussein, chief of staff to KRG President Masoud Barzani, told Human Rights Watch that the regional government had no policy of building destruction or discrimination against Arabs, but that “individual mistakes” may have occurred.[35] In a meeting with Human Rights Watch on July 28, 2016 discussing alleged violations by KRG forces President Barzani said, “Today ISIS broke all the rules. Their crimes are so huge that some of our people went beyond their instructions.”[36]

Kirkuk Governorate

Witness accounts, satellite imagery, and on-site visits point to unlawful destruction of properties in 17 villages in Kirkuk governorate that Peshmerga forces had recaptured at various points in 2015, in addition to one site of destruction in 2016. We chose to investigate these sites based on initial indications of destruction and their diverse locations. Second-hand accounts Human Rights Watch received and satellite imagery reviewed suggests there is a likelihood that many more villages were destroyed in Kirkuk governorate during this period – satellite imagery alone shows more than 60 severely or totally destroyed villages in Kirkuk governorate.

The KRG’s fact-finding committee acknowledged building destruction in Kirkuk governorate, but stated that “no property was intentionally destroyed and those properties which were damaged were solely due to the unfortunate consequences of war” such as, in particular, coalition airstrikes, but also ISIS’s planting of IEDs in homes, and artillery, rocket, and mortar fire. The committee also wrote, “Another prominent reason for the destruction of property has been the presence of non-KRG affiliated militias and hostile civilian elements which have in some cases destroyed segments of property in a village or region.”

West of Kirkuk City

Qarah Tappah

Building demolition by security forces using bulldozers in at least one village occurred as recently as May 2016.

In Qarah Tappah, a village of over 2,600 Arab inhabitants 14 kilometers west of Kirkuk city, a combination of Peshmerga, Asayish, and Kirkuk police arrived on the morning of May 5, 2016. This was one day after security officials had arrested 42 villagers on suspicion of involvement in explosions that had occurred the previous day at two nearby wells of the Khabbaz oil and gas fields.[37]

Villagers told Human Rights Watch that they saw one security official go around the village and write a red “X” on over two dozen houses, which they later learned marked them for destruction.[38] The residents of Qarah Tappah told Human Rights Watch that the security forces had gathered them in a field next to the village the previous day, while a masked informant pointed out village men whom the security forces then arrested. Thereafter, the security forces ordered the residents back into their houses, from where they observed the marking of houses later the same day.

According to residents, the military-uniformed drivers of four bulldozers went to different parts of the village and began destroying the marked houses. Overall, they destroyed 28 houses: 16 concrete block houses and 12 mud brick houses, villagers said.[39] In a brief tour of the village, Human Rights Watch observed 18 destroyed houses. The remains of several walls were still marked with a red “X.” In addition, researchers observed wide tire tracks leading to destroyed houses and damage on the corners of two houses along a narrow passageway where residents said the bulldozer did not manage to pass through.[40] The destroyed houses did not belong to those arrested the previous day on suspicion of blowing up the two nearby oil wells, villagers said, but for the most part to villagers who neighbors and relatives said had joined ISIS long ago.[41]

Three villagers told Human Rights Watch that they remained in the village and saw Rawand Mala Mahmud, an official of the Kirkuk branch of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK, one of the region’s two leading political parties) at the scene and heard him order the destruction. The villagers said fellow security officers referred to Rawand Mahmud by name.[42]

The destruction of homes in Qarah Tappah was not related to military operations against ISIS, and appeared to constitute attacks on civilian objects, a serious violation of international humanitarian law.

Dindar Zebari, head of the KRG Foreign Relations Department’s Committee to Evaluate and Respond to International Reports, in a September 2016 communication, said that 18 homes of persons alleged to be armed members of ISIS were destroyed and 10 others marked with an “X” “by the head of the village and other local residents.” He said that some homes were destroyed when security forces were unable to disarm IEDs found in them.[43] In a separate response Falah Mustafa Bakir said, regarding Qarah Tappah, that “Kurdish forces did demolish 20 houses which belonged to terrorists, most of whom are still active within the ranks of the Islamic State.”[44]

Eight kilometers southwest of Qarah Tappah are the three villages of Idris Khaz’al, Idris Khubbaz, and Idris Hindiya Qadima. On the night of January 29-30, 2015, ISIS took control of Idris Khaz’al and Idris Khubbaz but not Idris Hindiya Qadima, according to residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch. The residents said they did not see ISIS booby-trap buildings there. When Peshmerga forces took control on the evening of January 31, 2015, they ordered the few remaining villagers to leave.[47] According to witnesses, a combination of Peshmerga, Asayish, and civilian Kurds, using bulldozers under the direction and protection of Peshmerga forces, destroy buildings in all three villages.[48] The villagers said they saw the beginning of the destruction from within the villages as the Peshmerga ordered them to leave Idris Khaz’al and Idris Hindiya Qadima, and observed destruction from two checkpoints less than 500 meters away from all three villages a few days later.[49] The villages numbered between 70 and 100 houses each, and the residents were Sunni Arabs.[50] Satellite imagery from February 5 and 14, 2015, after the Peshmerga recaptured the area, show destruction of large parts of the three villages Idris Khaz’al, Idris Khubbaz, and Idris Hindiya Qadima consistent with the use of fire, heavy machinery and possibly high explosives.

Villagers told Human Rights Watch that as they were leaving Idris Khaz’al on the night of January 31, they saw trucks carrying bulldozers drive into the village, which was by then under Peshmerga control, and others on the road to the village.[51] On February 1, other villagers said they had been at a Peshmerga checkpoint within sight of Idris Khaz’al and saw bulldozers destroying houses in the village.[52] On February 3, more villagers came to the checkpoint and observed the damage.[53]

A villager from Idris Khaz’al told Human Rights Watch that on February 3 he saw a group of about 11 armed men, dressed like Kurds and speaking Kurdish, looting, burning and demolishing our homes with a bulldozer.[54] He said that he informed Captain Rizgar of the Peshmerga, whom he knew personally, but that Captain Rizgar said he was powerless to stop them.[55]

Human Rights Watch visited Idris Khaz’al on November 24, 2015, and observed that almost all buildings belonging to roughly 70 resident families had been demolished; there were signs of fire damage in several houses and almost no usable household goods remained.

Villagers told Human Rights Watch that airstrikes had hit two houses, one on each end of Idris Khazal, as well as ISIS vehicles. Peshmerga artillery rounds also landed in the village but did not cause much damage, they said.[56]

A villager who said he remained in Idris Khaz’al during the 36-hour ISIS occupation said that ISIS took some objects but did not generally loot or demolish buildings. Shelling by Peshmerga forces did hit a few houses, he said, and an airstrike demolished two buildings at each entrance to the village as well as cars of ISIS fighters.[57]

Another villager from Idris Khaz’al said that Peshmerga ordered him out of Idris Khaz’al on January 31, 2015, and that he first returned, briefly, after three days, when he saw houses destroyed and others on fire. He said he was able to return for good following an order from Najmaddin Karim, governor of Kirkuk, after 10 days, and at that point found the village destroyed.

Idris Khubbaz, about one kilometer to the north, resembled Idris Khaz’al, although a greater number of homes and other buildings remained standing. A villager told Human Rights Watch that he saw, from a checkpoint outside Idris Khubbaz, several bulldozers destroy houses after the Peshmerga recaptured the village on January 31.[58]

In Idris Hindiya Qadima, about 2 kilometers southeast of Idris Khaz’al, villagers told Human Rights Watch that although ISIS had never entered their village, Peshmerga and Asayish forces, together with armed Kurdish civilians, destroyed much of the village after ordering them to leave on January 31.[59] One villager said that when he tried to stop an armed man in military dress speaking Kurdish from bulldozing his shop, the man threatened him at gunpoint and proceeded with the destruction. The armed men wore civilian dress as well as Peshmerga and Asayish uniforms, and mostly spoke Kurdish, a villager said, but they also spoke in Arabic to villagers who were leaving.[60]

Another villager said he saw four yellow bulldozers driven into the village under Peshmerga control. He said of the around 60 houses at least 30 had been destroyed.[61]

In its March 2016 response to Human Rights Watch, the KRG wrote that in the three Idris villages, ISIS “could not plant IEDs in this district as Peshmerga forces immediately launched a counterattack to liberate these areas.” However, in its June 2016 response, the KRG stated that a “Sheikh [from Idris Hindiya Qadima] asserted that the sole reason [for the] large level of destruction in his village was due to IS planted IEDs and the exchange of fire during the conflict situation between IS and the Peshmerga forces.” Regarding Idris Khaz’al, the KRG stated that “a local Arab tribal leader” claimed coalition airstrikes and IEDs “unavoidably detonated in the cleaning-up mission by engineering teams” destroyed three quarters of the 84 destroyed properties. The KRG did not account for the remaining 21 buildings destroyed or say why detonation of the IEDs was “unavoidable.”[62] For Idris Khubbaz, according to the KRG response, causes of the destruction “were the same as in Idris Khaz’al.”

The information provided in the June 2016 KRG response is at odds with accounts villagers gave to Human Rights Watch regarding the short duration of ISIS’s control and their claim that they did not observe ISIS planting IEDs, as well as consistent accounts that ISIS never reached Idris Hindiya Qadima. A rivulet between Idris Khaz’al and Idris Hindiya Qadima marked the line of ISIS’s furthest eastward advance there.[63] Most of the destruction in Idris Khaz’al occurred between after the Peshmerga retook the village on the night of January 31 - February 1 and February 5, calling into question the claim that demining teams had quickly determined the necessity of setting off IEDs planted by ISIS.

Multaqa, a village along the water canal 2 kilometers southwest of Idris Khaz’al, was also destroyed and no civilians had returned, villagers from the area told Human Rights Watch, but researchers could not visit the area to verify the accounts due to security restrictions.[64] Satellite imagery shows over 90 percent of village buildings there were demolished, likely with high explosives, between February 14 and August 29, 2015.

Other villages northwest of Kirkuk city that remained within Kurdish security forces’ control also displayed extensive building destruction with signatures consistent with the use of fire, heavy machinery and high explosives. The sheer extent of building destruction and the type of damage signatures identified in these villages was not consistent with air or artillery strikes.

A few kilometers further northwest of Qoshkaya, along the road to Dibis, Human Rights Watch saw that isolated structures around the villages of Mar’i and ‘Amsha were completely destroyed, exhibiting similar signs of destruction as in Qarah Tappah, the Idris villages, and Qoshkaya. Human Rights Watch found no villagers to interview about the circumstances of destruction.

Western Arc from Maktab Khalid to Maryam Bek

Satellite imagery shows significant destruction consistent with accounts by residents in an area resembling an arc from the major intersection at Maktab Khalid to al-Murra, Shahid, Yarmuk and Maryam Bek, and comprising the villages of Abu Ka’uba and Nahrawan—all Arab villages, some built during Saddam Hussein’s Arabization campaign in the mid-1980s. Of these villages Human Rights Watch was only able to visit Maktab Khalid, which had been entirely razed to the ground.

Maktab Khalid

Battles to expel ISIS from Maktab Khalid took place starting on January 29, 2015, with further skirmishes in February and March 2015.[68] Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that ISIS attacked Maktab Khalid in February 2015 but did not occupy the village and Peshmerga forces retained control.[69] Peshmerga repelled another ISIS attack in early July 2015, according to media reports.[70] By November 24, 2015, when Human Rights Watch visited, there was barely a stone standing, and Peshmerga fighters were sifting through the rubble for valuables. Peshmerga pointed out large craters by the side of the road that they said came from coalition airstrikes, but similar craters were not visible in the formerly built up areas north and south of the main road. Satellite images from the mornings of February 5 and February 14, 2015 show that the near complete destruction of the village occurred in this nine-day period. Further satellite imagery shows that the commercial part of the village south of the main road was destroyed between May 2015, and March 2016. In late November 2015, Maktab Khalid was in a no-man’s land stretching several kilometers to the west and just in front of Peshmerga defensive positions, Peshmerga officers told Human Rights Watch.

The KRG in its response to Human Rights Watch about this area cited as causes of destruction “coalition airstrikes,” “clashes between Peshmerga forces and IS,” and vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices “detonated amidst … homes.” The response said that in Maktab Khalid, ISIS planted more IEDs “than [in] any other village in the Kirkuk governorate,” booby-trapping nearly all homes.

Human Rights Watch found that the destruction of Maktab Khalid mainly took place at a time when the area was under Peshmerga control. While air strikes and heavy ground fighting could well account for destruction of a number of buildings, damage signatures for the most part are consistent with demolition using high explosives and heavy machinery. The KRG did not argue or provide evidence that imperative military necessity required demolishing homes to detonate what the KRG states were ISIS-planted IEDs, thereby destroying the entire village. The KRG response did not address why the Peshmerga did not cordon off the village and leave the IEDs in place and to be dismantled later.

Al-Murra, Shahid, and Nearby villages

In June 2014, ISIS took control of al-Murra, 4 kilometers southwest of Maktab Khalid.[71] Peshmerga regained control in February 2015, a resident told Human Rights Watch.[72] The Institute for the Study of War, which monitors developments involving ISIS in Iraq, reported that ISIS attacked Peshmerga forces in al-Murra on April 20, 2015.[73] The seemingly privately maintained Facebook page “News of the Peshmerga Heros” (اخبار البيشمركة الابطال) reported Peshmerga forces in control of al-Murra on July 6, 2015, showing Peshmerga with bodies of ISIS fighters there.[74] A resident of al-Murra said there had been a brief ISIS attack on al-Murra in July 2015.[75]

This resident said he had stayed in the village while it was under ISIS control until late September 2014. He said he then decamped to ISIS-controlled Garha village, between the towns of Rashad and Riyadh, before returning to al-Murra after learning that Peshmerga had captured the village in February 2015.[76] He said that he found a portion of the houses in al-Murra destroyed; he said he did not know by whom or how, but that ISIS had not destroyed houses in the months he had stayed there.

Another villager from al-Murra gave Human Rights Watch a similar account. Before he left the village in December 2014, he said, there had been some shelling into al-Murra.[77] On May 4, 2015, he crossed from al-Aghair in ISIS-controlled territory to al-Murra, which he had heard the Peshmerga had recaptured. He said that during the crossing with other families, two girls died from an IED, and others were injured, including five of his children. He said he briefly went through the village, finding it largely intact, before taking his children to a hospital in Kirkuk. When he returned 10 days later to al-Murra, he said, his house was intact, albeit looted, with Peshmerga and Kirkuk police present in the village blaming one another.[78] The Peshmerga ordered him out of the village in late June 2015, he said, and he went to nearby Yarmuk. The Peshmerga repelled an ISIS attack in early July, a week after he left, he said, and after that they brought bulldozers to demolish the village in the presence of local police. The villager said his account was based on his own observations and the account of a relative who was with the Peshmerga.[79] He said the Peshmerga used explosives to destroy the mosque and school, as seen in a video he said his relative had taken.[80]

The first villager from al-Murra also told Human Rights Watch that in July 2015 Peshmerga warned him and other villagers to leave al-Murra due to an impending battle. ISIS briefly retook al-Murra, he said, but Peshmerga drove them out again within five hours in one night. He said he observed the battle from the vicinity of nearby Yarmuk. The villager said he approached to within about a kilometer of al-Murra in the two weeks after the July battle and could see people blowing up houses.[81]

Satellite images of al-Murra from May 20, 2015 indicate relatively little damage to structures in the village. Images from November 12, 2015 show extensive destruction, with virtually all building structures reduced to rubble, consistent with the use of high explosives and heavy machinery.

In its March 26, 2016 reply to Human Rights Watch, the KRG stated, “The village of Murah is currently under the control of the IS terrorist network.” In May 2016, villagers from al-Murra who said they were in touch with Peshmerga there told Human Rights Watch it was then under Peshmerga control, just outside a berm the Peshmerga had constructed.[82]

Satellite images show extensive building destruction occurring in Shahid between May 20 and November 12, 2015.[83]

The KRG’s September 2016 response does not directly address the question of whether Peshmerga forces were responsible for the destruction in al-Murrra and al-Shahid, saying only that the villages were “three kilometers away from the nearest Peshmerga forces frontline position and thus do not constitute an area which is under the authority of the Peshmerga forces.”[84] In his response, Minister Falah Mustafa Bakir said that “Kurdish forces have withdrawn from these two villages by a distance of approximately 3 kilometers and the destruction of houses inside these two villages is also directly related to the fact that the properties belonged to individuals who had joined the terrorists of the Islamic State and that those houses were being used by the terrorists with the aim of strengthening their presence in these villages.”[85] This argument does not satisfy the requirement under the laws of war that to be lawful property destruction must meet a concrete military objective (military necessity) and not be excessive or indiscriminate.

Satellite imagery also shows extensive building destruction occurring in Yarmuk, although at a later period, between November 12, 2015 and January 24, 2016. The KRG, in its June 2016 response, stated that although Yarmuk was on the frontline, “the properties of [Yarmuk] have remained largely intact and were not subject to any damage.” According to the Institute for the Study of War, on June 11, 2015 Peshmerga forces repelled an attempt by ISIS to set up positions in Wastana, a few kilometers south of Yarmuk.[86]

Villagers from al-Murra, Shahid, and Yarmuk told Human Rights Watch they briefly lived in or passed through Yarmuk and found it largely intact as of mid-July 2015.[87]

Two villages between Maktab Khalid and Maryam Bek, Nahrawan and Abu Ka’uba, show extensive destruction in satellite imagery. Satellite imagery on May 20, 2015, indicates extensive fire-related building destruction in Abu Ka’uba’s western part; imagery from November 12, 2015, shows the entire village destroyed, and damage signatures consistent with the use of high explosives and heavy machinery.

A villager from Shahid said that Abu Ka’uba, like Yarmuk, lies on the Peshmerga-controlled side of the berm the Peshmerga erected as the front line later in 2015. The villager claimed that following ISIS attacks on Maktab Khalid in December 2014, Peshmerga had demolished Nahrawan, one of the villages built under Saddam Hussein’s Arabization campaign in the 1980s. Satellite imagery confirms that Abu Ka’uba, Yarmuk, and Nahrawan are on the Peshmerga side of the berm, while Maktab Khalid, al-Murra and Shahid lie just on the other side, but in an area defensively controlled by the Peshmerga.

In its response to Human Rights Watch, the KRG wrote, without giving dates, that the destruction in Nahrwan was the result of heavy coalition airstrikes, which satellite imagery also shows, and IEDs planted by ISIS. The response does not address how or why the IEDs were set off. The KRG response asserted that Peshmerga in the village stopped people from neighboring villages from destroying homes in Nahrawan.

The Arab villages of Sa’d and Khalid are located 2 kilometers west of the Kirkuk-Tuz Khurmatu highway at about mid-point between Taza and Daquq. Wahda, a third village, lies almost directly west of this main road, 2 kilometers further south.

Villagers from the three villages told Human Rights Watch that they stayed a few months after June 2014 under ISIS but left before an impending battle with Peshmerga in late September 2014.[88] According to two of the villagers, ISIS confiscated private cars, livestock, and some tractors but were otherwise not present inside the village, controlling it from the outskirts.[89] Before the September battle, ISIS shelled the area, killing 15 people and wounding 33 including local Arab fighters defending the village as well as civilians. When the villagers left, they said, all the houses were largely intact.[90]

ISIS fended off the Peshmerga in September 2014 but five months later, in mid-March 2015, Peshmerga recaptured the area, including the three villages. The Institute for the Study of War, a Washington-based military affairs research institute, quoted Wasta Rasul, the commanding Peshmerga officer for the region, as saying that on March 9, 2015, “the Peshmerga launched an operation to clear the Tel al-Ward area, the Maktab Khaled area, and Wahda village, southwest of Kirkuk city.”[91] The institute earlier reported on February 10 that “coalition airstrikes targeted ISIS gatherings and a headquarters in the [three] villages,” adding that Peshmerga also fired artillery and mortars into the area.[92]

Villagers told Human Rights Watch that the Peshmerga took three of them back to the villages as local guides. One of the three told Human Rights Watch that apart from some damage from shells and bullets, Wahda’s houses were standing when the Peshmerga took over.[93]

After village elders met with Aso Mamand, the Kirkuk head of the PUK, the dominant Kurdish party in the area, villagers said, he briefly allowed them back to their homes, two days after the battle. In Wahda, one villager said, almost all houses were burned, but not destroyed, with all belongings gone. Another villager said that when he returned two days after the battle to Sa’d, his house was still smoldering, the entire village burned down, and seven houses demolished. The one villager who accompanied the Peshmerga said he had seen most belongings in place and no fires immediately after Peshmerga had driven ISIS from Sa’d and Wahda. Satellite imagery shows evidence of fire-related damages to a majority of buildings in the three villages occurring between February 14, 2015 and April 5, 2016.[94] Based on accounts by local residents, diplomats, humanitarian workers and the Peshmerga, the US-based website Foreign Policy in July 2015 reported from Wahda that, consistent with the account villagers gave to Human Rights Watch, most homes were intact and belongings in place when the local scouts accompanied the Peshmerga into the village in mid-March 2015.[95] Several days later, according to a village elder, “The Peshmerga … entered the village [and] brought a Kurdish mafia specialized in taking everything – wiring, washing machines, everything we owned.”[96]

The KRG response stated that coalition airstrikes and “Katyusha rockets, large mortar rounds, and artillery” caused destruction in Wahda and Khalid, and that ISIS booby-trapped homes there. The response did not address destruction in Sa’d, or allegations of looting and arson in all three villages.

On December 2, 2015, Human Rights Watch researchers accompanied Peshmerga to the frontline at Al-Bu Muhammad, 12 kilometers southwest of Daquq. The Peshmerga were finishing construction of a berm just west of Al-Bu Muhammad. A Peshmerga colonel told Human Rights Watch that ISIS had heavily mined the village, which Peshmerga had retaken in August, and that they exploded ISIS’s IEDs remotely.[97]

Human Rights Watch found the small, mostly Arab village entirely destroyed, with only some mudbrick walls still standing and few roofs intact. The village was devoid of household items or other belongings.

Pointing northwest from an outpost on the front line, Peshmerga fighters said that the three villages of Lower and Upper Dilis and Tel Rabi’, now in a no-man’s land defensively controlled by the Peshmerga, were also destroyed as a result of airstrikes and Peshmerga detonation of ISIS-planted IEDs.[98] Satellite imagery of the villages shows them almost completely razed by methods not solely attributable to airstrikes.

Nineveh Governorate

In Nineveh governorate, Peshmerga recaptured the area between Sinjar mountain and Mosul Lake from ISIS between late August and December 2014. Peshmerga established control over Zummar subdistrict from the Syrian border in the west up to, but not including, Zummar town in the east, by early September 2014. Control over Zummar town changed back and forth between ISIS and the Peshmerga, who took and finally held it in late October 2014. Since early 2015, the recaptured territories have remained largely free of incidents.[100]

In December 2014, Human Rights Watch documented the destruction of large numbers of Arab homes, and in some cases entire Arab villages, in areas in Nineveh’s Zummar subdistrict that at the time of our visit were under Peshmerga control. Human Rights Watch published these findings in February 2015, including statements by Peshmerga and Asayish officials claiming that such destruction occurred during battles, including by coalition airstrikes and ISIS forces.[101]

Information Human Rights Watch subsequently obtained in July and August 2015 indicates that Peshmerga and Asayish forces were responsible for destruction in the days, weeks, and months following their recapture from ISIS, in particular in three villages in Zummar subdistrict that Human Rights Watch visited: Sheikhan, Hamad Agha, and Barzan, and also in the town of Bardiya.

An analysis of satellite imagery from various points in 2014 and 2015 shows that, in addition to the initial destruction Human Rights Watch documented in December 2014, significant additional destruction occurred in early 2015, at a time when the area was not an active battlefield. A Human Rights Watch visit to the area in August 2015 found evidence corroborating this.

Only a few days after ISIS swept through the Nineveh Plains in the first days of August 2014 and routed Peshmerga from Sinjar and other towns, Kurdish forces launched a counterattack, moving along the southern shores of Mosul Lake southeastward.[102] The area has a mixed population of Arabs and Kurds, as well as some Yezidis.[103]

Kurdish forces recaptured Rabi’a town in early October 2014 and Sunune, further south, in late December 2014.[105]

Allegations of Peshmerga destruction of homes after the battle, in violation of the laws of war, surfaced almost immediately.[106] A journalist who interviewed Arab and Kurdish villagers, as well as Peshmerga, documented destruction of Arab homes in Sheikhan, nearby Umar Khalid, and Barzan in September 2014. His interlocutors acknowledged that Peshmerga and Kurdish civilians burned down, looted, and destroyed homes in revenge.[107]

Zummar Subdistrict

In August 2015, Human Rights Watch met five Kurdish farmers from the intact Kurdish village of Kani Azeir (Ewes). They said they were farming fields of Arab villagers from Sheikhan, about 2 kilometers to the west, and that the Arab owners had left with ISIS to Mosul after the Peshmerga retook the village in late August 2014.[108] They said that ISIS had destroyed some structures in Sheikhan in the three weeks of its presence there in August 2014 but that they, along with other Kurdish farmers from surrounding areas and Peshmerga forces, burned homes and demolished the town of Sheikhan after the Peshmerga retook it in late August 2014.[109]

The Institute for the Study of War reported on August 22, 2014, the beginning of a Peshmerga offensive, supported by US-led coalition airstrikes, in Zummar district.[110]

Human Rights Watch visited Sheikhan, in Zummar subdistrict, on August 3, 2015, and found that almost no structure remained intact, with the exception of a green mosque.

The KRG response to Human Rights Watch regarding Nineveh governorate stated that, “in the village of Sheikhan, which is located on the frontline, half of the properties were destroyed due to the exchange of fire (170 houses, 85 of which were destroyed) … due to artillery and mortar strikes.”

Hamad Agha itself, just inside Rabi’a subdistrict, has a Kurdish part along the main road (in some maps, this is part of Ewes) and an Arab part further south. When Human Rights Watch visited on August 3, 2015, the Kurdish part was intact while the Arab part was destroyed. The policeman told Human Rights Watch that he participated with Peshmerga in demolishing the Arab part of Hamad Agha, a short distance south, away from the main road, where Human Rights Watch could clearly see the destroyed houses.[112] Satellite imagery analysis shows 177 destroyed buildings in Hamad Agha, representing over 98 percent of the village. The majority of buildings were likely demolished with heavy machinery or burned down between June 7 and September 7, 2014. Building demolition continued with the remaining larger building structures likely demolished with high explosives around November 5, 2014.

The KRG response to Human Rights Watch’s findings stated that in “the village of Hamad Agha … 120 houses were destroyed … due to artillery and mortar strikes.”

The KRG March 2016 response to Human Rights Watch noted that Bardiya, a town 8 kilometers east of Hamad Agha, in Zummar subdistrict, “and its surrounding areas, is populated by Kurdish villagers (the Hasini tribe to be precise) and has no Arab population.” Human Rights Watch visited Bardiya on August 3, 2015, and met with Kurdish residents and officials and one Sunni Arab policeman from a nearby village. The Kurdish residents said that they had lived side-by-side with their Sunni Arab neighbors for years without incident, and could not believe some of them joined ISIS.[113] While Human Rights Watch cannot say what portion of Bardiya’s residents are Sunni Arab, local residents indicated that Sunni Arabs lived among them.

Right behind the offices of the KDP in Bardiya is an open area with the adjacent houses destroyed. Officials and residents said that ISIS destroyed about 10 houses in the town belonging to Kurdish security officers in the three or four weeks they were in Bardiya in August and September 2014.[115]

The KRG in a June 5, 2016 email message wrote that in Bardiya, “83 houses were destroyed by airstrikes.”[118] The June 30 KRG response to Human Rights Watch does not address building destruction in Bardiya.

During a December 2014 visit to Zummar subdistrict, Human Rights Watch found that walls near some destroyed homes were spray-painted with anti-Arab slogans. Only Kurds had resettled there since the Peshmerga had routed ISIS by October 2014, and many homes in the Arab quarter bore signs of having been torched. Graffiti on one wall read “Endowment of Islamic State” in Arabic, with the words “Islamic State” crossed out and replaced with “Kurds.” Several residents pointed to the ruins of one home and said they saw Peshmerga bulldoze it because it had belonged to an alleged Sunni Arab ISIS collaborator. Some Kurdish residents said that they saw local Kurds destroy Arab homes in Bardiya, Sheikhan, and Barzan upon their return, while others said they saw Peshmerga do it.[119]

Satellite images from between June 2014, and March 2016, show three distinct areas of destruction in Bardiya, with overall 365 buildings destroyed, the overwhelming majority after January 2015, by which time the Peshmerga had firmly established control. By late October 2014, Peshmerga forces had taken the town of Zummar, 20 kilometers south of Bardiya.[120] Human Rights Watch is not aware of ISIS attacks on areas north of Zummar after this date. Satellite images taken between January and December 2015, show destruction of over 200 buildings in Bardiya during this period.

They said that after Peshmerga recaptured Barzan, no other forces entered the village, but every day for several weeks they heard explosions from their village, at least three per day, and one day as many as 27 explosions. From Sumud and the checkpoint, they said, they saw flames and smoke from burning houses. They said that they did not see airstrikes in that period.[123]

The KRG response to Human Rights Watch stated that “[a] large majority of properties in the village were subject to arson attacks by large groups of Yazidis in retaliation for [the residents’] participation in the mass-killing of Yazidis.” The response says the Peshmerga efforts to stop the arson failed because “the sheer number of Yazidi residents proved too overwhelming.” Regarding building destruction, the KRG wrote that “523 homes were destroyed in Barzanke village, including those that were subject to IS IEDs,” leaving open who carried out the destruction. The reasons for “targeting” Barzan “particularly severely” was its role as the “epicentre of the IS groups support base … as well as a recruitment hub for IS fighters and IS commanders [and it being the home to] many of the perpetrators of the mass-killing of Yazidis.” This argument does not satisfy the requirement under the laws of war that to be lawful property destruction must meet a concrete military objective (military necessity) and not be excessive or indiscriminate.

Satellite images indicate that at least a quarter of the destruction in Barzan occurred after November 5, 2014, when no skirmishes occurred in or around the village and it was under Peshmerga control.[124]

According to the US Department of Defense, US airstrikes against ISIS between early August and mid-September 2014 “near Mosul Dam” hit 10 fighting positions, 3 mortar positions, 3 machine gun positions, 3 buildings, and 10 IED emplacements, in addition to vehicles and checkpoints. The roughly thirty strikes are insufficient to account for the destruction of several entire villages, and witnesses reported only a few airstrikes on Barzan village.[125]

III. Legal Standards

International humanitarian law—the laws of war—governs the conduct of hostilities in armed conflicts as does international human rights law, which applies at all times.